APPENDIX A Description and Review of Research Projects in Three Cities

As the panel was completing its review of available research on needle exchange and bleach distribution programs and related issues, the Assistant Secretary for Health made public statements that a number of unpublished needle exchange evaluation reports had raised doubts in his mind about the effectiveness of these programs. The panel deemed these statements to be significant in the public debate, therefore necessitating appropriate consideration in order for the panel to be fully responsive to its charge. We therefore reviewed the unpublished studies—by investigators in San Francisco, Montréal, and Chicago—that had raised concerns. As unpublished findings, these studies lack the authority provided by the peer review and publication process. They have been considered, however, in the panel's presentation of its approach to the pattern of evidence on the effectiveness of needle exchange programs, which is discussed in Chapter 7. This appendix describes the individual studies and provides the panel's detailed review of the reported findings.

SAN FRANCISCO

The investigators (Hahn et al., 1995) collected data on demographic, sexual, and drug-use risk behaviors, treatment experience, living arrangements, HIV status, needle exchange participation, and number of needles exchanged through a structured interview in order to "examine use of the needle exchange program in San Francisco in the first two years after its commencement" (p. 1). The information on "needle exchange use" reported

by study participants allowed these researchers to examine predictors of needle exchange participation and to estimate HIV seroconversion rates among needle exchange users and nonusers. According to these authors, this information allowed them to "assess whether the San Francisco needle exchanges are reaching their intended clientele and whether the exchanges affect risk reduction and HIV incidence" (p. 3).

This study recruited 1,093 injection drug users from nine methadone maintenance and 21-day detoxification programs from 1989 through 1990, following the November 1988 opening of the Prevention Point needle exchange program in San Francisco. Each participant completed structured interviews (questionnaire) and had an HIV test performed at each repeat visit. Of those recruited, repeated questionnaire data and serostatus test results were available from 412 participants (38 percent). Needle exchange participation was determined by examining participants' questionnaire responses (needle exchange participation items) for their most recent treatment visit (methadone maintenance, 21-day detoxification, or both).

Descriptive analyses based on the entire sample of 1,093 study participants showed that males, frequent injectors, homeless people, residents of hotels and shelters, homosexuals and bisexuals, and participants who were aware of their HIV status were more likely to use the needle exchange. No association was detected between needle exchange use and the education level of study participants, the age of first injection, the number of years injecting, bleach use, or prostitution.

During the 1989 through 1990 study period, nine seroconversions were detected among the 412 repeaters who were initially assessed as HIV negative. The time at risk for study participants who remained HIV negative was years from first interview to last interview, whereas the time at risk measure for those who seroconverted was years from first interview to first HIV-positive interview. This resulted in an estimated overall seroconversion rate of 1.1 per 100 person years (95 percent confidence interval [CI]: 0.5 to 2.0 percent per person years) among the 412 repeaters. The estimated seroconversion rates for those who had never used the needle exchange was 0.33 percent per person years (95 percent CI: 0.05 to 1.02 percent per person years) compared with an estimated rate of 3.49 percent per person years (95 percent CI: 1.49 to 6.75 percent per person years) for those who had ever used needle exchange. More specific estimates of seroconversion rates among needle exchange users were derived for those study participants who had used the needle exchange for fewer than 3 months (6.26 percent per person years) and for those who had used the needle exchange for 3 months or more (2.19 percent per person years).

Results of a proportional hazard model indicated that, among the 412 repeat study participants, the hazards ratio for seroconverting was higher for those who had used the needle exchange (10.60; 95 percent CI: 2.20 to 51.06) compared with those who had not.

Finally, in an attempt to control for potential selection bias due to the self-selection of the 412 repeaters, standardized seroconversion rates accounting for differences in age, sex, race, and participation in methadone maintenance between repeaters and nonrepeaters were derived. The estimated standardized rates were found to be 1.12 percent per person years for the entire group, 0.51 percent per person years for those who had never used needle exchange, and 2.97 percent per person years for those who had ever used the needle exchange.

These findings were interpreted by the authors as indicating that needle exchange programs attract a high-risk, chaotic, and indigent population of injection drug users. The authors conclude that needle exchange programs are well suited for implementing HIV preventive interventions, in view of their findings that such programs provide direct access to high-risk injectors. Moreover, the authors state that it is unlikely that the extremely high HIV seroconversion rate among study participants who had ever used the needle exchange compared with participants who had never used the needle exchange, or that the large hazards ratio for seroconversion associated with needle exchange participation, is the result of needle exchange use itself. Several possible explanations are offered by the investigators: (1) most participants had a very brief exposure period to the needle exchange; (2) the highest seroconversion rates were observed in the subgroup with the lowest amount of time exposed to the needle exchange, which is less than 3 months, less than the typical detection window for the HIV antibody; and (3) seroconversion rates were not based on a fixed schedule (i.e., voluntary re-enrollment).

Review

The panel's main concern about this research is the potential misinterpretation of the reported findings. Although the authors do not attribute the observed disparities in seroconversion rates between needle exchange program participants and nonparticipants to exposure to these programs, their readers may misinterpret these study findings as reflecting the causal effect of needle exchange programs on seroconversion. As indicated by one of the investigators, the study design and analytical methods used by the researchers preclude such an assessment (Moss, 1995).

Indeed, for a number of reasons, the existing data are inadequate to assess a needle exchange effect by comparing the seroconversion rates of needle exchange users and nonusers. One possible strategy for attempting to make such an assessment would have been to estimate the seroconversion rate per injection drug user per unit of time at risk while exposed to the needle exchange with the seroconversion rate per injection drug user per unit of time at risk while not exposed to the needle exchange. This would have allowed a direct inferential test of the null hypothesis that the seroconversion

rate per unit of time exposed to the needle exchange equals the seroconversion rate per unit of time not exposed to the program. However, the data needed to test such a hypothesis were not available.

Another reason the data are inadequate to draw inferences about needle exchange effects is because needle exchange exposure was measured as weekly, monthly, infrequent, or never, so it is impossible to derive an accurate estimate of time at risk while exposed to the needle exchange. It is likewise difficult or impossible to draw sound inferences from this study about the effects of needle exchange on seroincidence rates because of uncertainties about the times of infection and the times of entry into the needle exchange program. The dates on which several seroconverters were first detected as HIV positive (note that we do not know when they actually seroconverted) were very close to the reported dates of entry into the needle exchange program; therefore, it is uncertain whether these individuals entered the program prior to exposure to the virus or after. This creates serious concerns regarding the quality and accuracy of the reported seroconversion rate estimates. Different methods of imputing these times could lead to substantially different results (Brookmeyer and Gail, 1994).

Another reason for the inadequacy of the data is that the "time at risk" measure for computing the seroconversion rates in this study was operationalized as being the years from first interview to last interview for study participants who remained HIV negative, whereas the time at risk measure for those who seroconverted was equal to the number of years from the first interview to the first HIV-positive interview. Another, more commonly used method for computing time at risk for seroconverters is to use midpoint imputation; that is, to compute the time estimate of infection by averaging the times of the last negative and first positive test results. Estimating in this way would substantially impact the reported seroconversion rates for needle exchange users and nonusers by changing their estimated time of becoming infected. A drastic change in the number of seroconversions occurring among needle exchange user and nonuser subgroups would result: five of the seven seroconversions among needle exchange users would be classified as having occurred prior to their participation in the needle exchange program. This example, taken in consideration with the small number of seroconverters, illustrates why it is impossible to reach any conclusion about seroincidence from this study.

Even if detailed information on needle exchange exposure times and times of infection were available, the tenability of the inferences that could be drawn from such an analysis would be subject to substantial challenges on the basis of sampling biases: bias in the HIV seroconversion rate estimates are bound to be present. First, the sample was decidedly not extracted from the needle exchange user and nonuser populations: the sample was drawn from a treatment population and as a consequence represents, at

best, a very select subpopulation group of injection drug users. Second, the sampling strategy adopted appears to have been dependent on client exposure time to treatment, meaning that treatment clients who spent extended periods in methadone treatment or made frequent visits to detoxification programs were more likely to be sampled, again creating a bias.

The panel concurs with the conclusions made by the authors that the observed differences in seroincidence rates across groups cannot be attributed to program participation, given the uncertainty regarding the time of infection and the lack of information concerning the needle exchange participants' intensity (dose) of exposure to the program. Moreover, although there are serious selection bias concerns associated with the reported HIV incidence estimates among program participants and nonparticipants, the San Francisco program does appear to attract individuals who are at high risk of infection, at least among injection drug users who have recently been in contact with treatment services.

MONTRÉAL

The Montréal CACTUS (Centre d'Action Communautaire Auprès des Toxicomanes Utilisateurs de Seringues) needle exchange program opened on July 9, 1989. It is a fixed-site program that operates 7 days a week from 9 p.m. to 4 a.m. In addition to exchanging needles, staff disseminate information on AIDS and the prevention of HIV transmission and distribute condoms, alcohol swabs, lubricants, bottles of bleach, and distilled water. CACTUS practices a policy of one-for-one exchange to a maximum of 15 needles with 1 extra needle per visit. The number of visits to the program stabilized at approximately 1,200 visits per week after 1 year of operation (Hankins et al., 1994).

Two research projects have provided needle exchange participation data on the Montréal program. The first is a formal attempt to evaluate the effect of the needle exchange program on risk behaviors, HIV prevalence, and HIV incidence (Hankins et al., 1992, 1994; Hankins et al., 1993). The second is a prospective epidemiologic study of HIV infection among injection drug users in Montréal that was initiated in 1988, one year prior to the opening of the needle exchange program (Bruneau et al., 1995; Lamothe et al., 1995).

Needle Exchange Evaluation Project

The evaluation study (Hankins et al., 1994) recruited volunteer program participants who were leaving the needle exchange site on one randomly chosen evening per week. Study participants were asked to provide a blood specimen for HIV antibody testing. Serology test results were linked by

means of a random bar code identifier to individual demographic and risk behaviors (in the previous 7 days) that were collected at each visit on a questionnaire on service delivery and behavior. Overall, 25 percent of the individuals approached agreed to provide a specimen; the 75 percent of program participants who declined indicated they were in a hurry. Yearly HIV prevalence estimates for the period of January 1990 through January 1993 are presented in Table A.1.

Seroincidence

Repeat test results on the same individuals using the random bar code identifiers were used to identify seroconversions and to estimate seroincidence for the same 3-year period (January 1990 through January 1993). The date of seroconversion was estimated as the midpoint between the last negative and first positive result. Hankins et al. (1993, 1994) reported that during that 3-year period a total of 13 of the 136 repeat participants seroconverted, for an overall incidence rate of 12.9 per 100 person years of observation (95 percent CI: 6.9 to 22.0).

Separate incidence estimates per year are provided in Table A.2. Participants who reported having borrowed or loaned needles in the previous 7 days were found to be substantially more at risk of seroconverting. Seroconversion was not found to be associated with age, sex, cocaine use, condom use, or the sexual orientation of males.

Data from Correctional Institutions

In a separate investigation undertaken to assess the degree of needle exchange program participant awareness, use, and satisfaction, Hankins et al. (1992) recruited injection drug users from three medium-security correctional institutions (n = 319) and one drop-in detoxification clinic (n = 173) for a brief structured interview (5 to 10 minutes). The sample of incarcerated injection drug users was originally recruited as part of an ongoing

TABLE A.1 HIV Prevalence Among Montréal Needle Exchange Participants

|

Year |

Seropositive |

Total |

Proportion (%) |

95% CI |

|

1990 |

49 |

442 |

11.1 |

8.4 to 14.4 |

|

1991 |

51 |

345 |

14.8 |

11.3 to 19.0 |

|

1992 |

45 |

270 |

16.7 |

12.4 to 21.7 |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Evaluating Montréal's Needle Exchange CACTUS-Montréal (Hankins et al., 1994:86). |

||||

TABLE A.2 HIV Incidence Rate Among the 25 Percent of Needle Exchange Participants Followed (Repeaters)

|

|

1990 |

1991 |

1992 |

Total |

|

Seroconversion |

6/111 |

7/85 |

0/19 |

13/136 |

|

Percent |

(5.4) |

(8.2) |

(0) |

(9.6) |

|

Person days |

16,510 |

16,707 |

3,588 |

36,805 |

|

Incidencea |

13.3 |

15.3 |

0 |

12.9 |

|

95 percent CI |

(4.9 to 28.9) |

(6.1 to 31.5) |

— |

(6.9 to 22.0) |

|

aPer 100 person years. SOURCE: Adapted from Evaluating Montréal's Needle Exchange CACTUS-Montréal (Hankins et al., 1994:89). |

||||

research project on risk factors for HIV infection among inmates in medium-security correctional institutions and included HIV antibody testing (Hankins et al., 1994). Results indicate that 73 percent of those interviewed had heard of the needle exchange program; 55 percent of this number had participated and 76 percent of them had used the program more than five times. Attenders expressed a very high level of satisfaction with the personnel (88 percent liked the staff), and 98 percent indicated that they had received the services they had requested.

An analysis of the serology test results shows that the overall HIV prevalence rate among incarcerated injection drug users was 10 percent (29/293). When needle exchange attenders were compared with nonattenders, program participants were found to be twice as likely to be HIV positive (14 and 7 percent, respectively). When the data are stratified by sex, this sizable disparity in HIV prevalence rates was not observed for female inmates; however, the rate was substantially higher for men (Table A.3).

Finally, Hankins and colleagues (1993) have reported meaningful reductions in risk behaviors among needle exchange participants. After the program opened, lending needles declined from 31 to 20 percent, and 62 percent of those who injected with used needles were doing so after having cleaned them with bleach compared with 30 percent in the first 2 months of operation.

Review

As with the San Francisco study, one of the panel's primary concerns with this research is the potential for severe bias in the prevalence and incidence estimates among needle exchange program users and nonusers. Given the nature of the samples studied and the shortfalls in the study

TABLE A.3 HIV Seroprevalence Rates (%) Among Incarcerated Injection Drug Users by Needle Exchange Participation

|

|

Attenders |

Non-Attenders |

Total |

|

Men |

8/39 (20.5) |

6/124 (4.8) |

14/163 (8.6) |

|

Women |

8/69 (11.6) |

7/61 (11.5) |

15/130 (11.5) |

|

Total |

16/108 (14.8) |

13/185 (7.0) |

29/293 (10.0) |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from Evaluating Montréal's Needle Exchange CACTUS-Montréal (Hankins et al., 1994:90). |

|||

design, it would be difficult for researchers to disentangle the potential causal effects of needle exchange programs on the outcome measures studied.

The seroprevalence base rates among needle exchange users reported by Hankins et al. (1994) are based on a 25 percent study participation rate. Clearly, this low participation rate raises concerns about the representativeness of the estimates and their accuracy in reflecting the HIV prevalence of the needle exchange user population. Moreover, the authors state that needle exchange participation stabilized at approximately 1,200 visits per week after the first year of operation. By assuming that a standard recruitment strategy was adopted over the 3 years of data collection, the number of recruited study participants—on which prevalence rates are based—dropped steadily over those 3 years and precipitously during the third year following the program opening (Table A.1). This latter observation further jeopardizes the representativeness of the derived prevalence estimates.

The same potential bias issues are relevant for the incidence rates reported in Table A.2. These are based on even smaller subgroups of those initial study participants who agreed to be tested more than once in a given year. Furthermore, the proportion of the initial base rate groups that were followed up in a given year also dropped substantially in the third year. Of the original 442 study participants in 1990, 25 percent were repeaters (111 of 442); this proportion remained stable in 1991 and dropped to 7 percent (19 of 270) in 1992.

To assess the potential effect of needle exchange participation on HIV prevalence, the investigators relied on data collected from a sample of incarcerated injection drug users who were part of an ongoing research project with another objective: identifying risk factors for HIV infection among inmates. The substantially higher prevalence rate observed among needle exchange program users compared with nonusers (especially for men) is disconcerting. Hankins et al. (1994) also report that incarcerated needle exchange program users were engaging in many more high-risk behaviors—e.g., using needles previously used by an HIV-positive person, receiving income from prostitution—than inmates who did not use the needle exchange

program. Because this study examines only seroprevalence rates, neither the timing of the infections nor the temporal link needed to establish the viability of a causal effect for the observed relationship between serostatus and needle exchange program participation (i.e., seroconversion before attending needle exchange) can be determined.

The population sampled also precludes generalizing these findings to the needle exchange user population or to the total population of injection drug users in Montréal. Specific idiosyncrasies of the studied samples directly impact the magnitude of the observed relationships (i.e., properties of the distribution of the variables studied). Although the magnitude of the observed associations (as assessed by odds ratios) is not affected by the shapes of the conditional distributions, their shapes (as assessed by the sample studied) are nonetheless assumed to be representative of the population distributions to which the estimated associations are being generalized.

Given the severe selection bias issues associated with the reported HIV seroprevalence and seroincidence rates among program participants and with the seroprevalence rates among the sampled incarcerated population, the panel concludes that this evaluation study cannot provide valid estimates of program effects on HIV prevalence and incidence.

Epidemiologic Study

Researchers at St.-Luc Hospital in Montréal (Lamothe et al., 1995; Bruneau et al., 1995) initiated a prospective epidemiologic study of HIV infection among injection drug users in September 1988. Active injection drug users who had injected drugs in the past 6 months were recruited from the street (with offers of free HIV testing and precounseling) and from drug treatment programs. The proportion of study participants recruited from treatment programs represents approximately 10 to 15 percent of the total cohort (Bruneau, 1995). Study participants were followed at 6-month intervals and were paid $10 at each visit to complete a structured interview including information on sociodemographic, sexual, and drug-related behaviors and to provide a blood sample for HIV antibody testing. Bruneau et al. (1995) reported on the association between needle exchange attendance (as assessed by one questionnaire item) and HIV infection status among injection drug users by conducting three series of analyses to identify: (1) baseline determinants of HIV seroprevalence, (2) entry determinants of HIV seroincidence, and (3) follow-up determinants immediately preceding HIV seroconversion.

Seroprevalence

By September 1994, the open cohort had an enrollment of 1,506 participants. At entry, 11.1 percent (167/1,506) were HIV positive. The odds

ratio of HIV positivity at entry for needle exchange program attenders (i.e., those who had attended at least once in the last 6 months) versus nonattenders was 3.4 (95 percent CI: 2.4 to 3.9). The final solution of the logistic regression model revealed that the adjusted odds ratio for HIV positivity at entry and needle exchange program attenders versus nonattenders was 2.7 (95 percent CI: 1.8 to 4.1). Adjustments were made for study entry, gender, language, age, and several other sociodemographic and sexual and drug-use risk behaviors. In addition to needle exchange program participation, variables found to be associated with seropositivity at entry included: education, income level, and the number of sex partners in the last 6 months. Furthermore, several drug-use risk behaviors were found to be associated with HIV positivity at entry, including: drug of choice; number of times injected drugs in the last month; participated in the needle exchange during the last 6 months; injected drugs in shooting galleries during last 6 months; injected drugs while in prison; ever shared injection equipment; acquaintances known to be HIV positive; and ever shared injection equipment with HIV-positive person.

Seroincidence

Of the 1,339 study participants who were not seropositive at entry, 75 had no follow-up data due to their recent enrollment date and 354 (25 percent) were lost to follow-up. Of the remaining 910 participants followed up (median follow-up was 15.3 months), 77 seroconverted, for an overall incidence of 5.0 per 100 person years (95 percent CI: 3.9 to 6.2). An upward trend in incidence rates was found when these rates were examined over three consecutive 18-month periods: for the period of September 1988 through February 1990, an estimated incidence rate of 4.5 percent was observed. This was followed by an incidence rate of 7.5 percent during the second 18-month period and a 9.8 percent rate during the 18 months after September 1991. At entry, the odds ratio of becoming HIV positive based on needle exchange participation (attenders versus nonattenders) was 2.5 (95 percent CI: 1.6 to 4.0).

To further explore the association between needle exchange participation at enrollment and subsequent seroconversion, a proportional hazards model was used with adjustments for the following variables: age; entry period; number of times used drugs in previous month; number of partners sharing injection equipment in previous month; number of acquaintances known to be HIV positive; participation in drug abuse treatment; other sources of injection equipment; and drug of choice. Although noteworthy, the resulting hazards ratio for needle exchange program attendance did not reach statistical significance.

Finally, to try to identify potential determinants immediately preceding

HIV seroconversion, a logistic regression model was fit to a nested case-control design, with the 77 seroconverters as cases and 279 matched controls (matched on gender, language, year of enrollment, and age). This analysis used information on sociodemographic variables, sexual behaviors, and drug-use risk behaviors collected during the last follow-up interview session preceding seroconversion. For the purpose of this analysis, a needle exchange program use variable was derived based on the sources of needles available to the participants, and cases were categorized as the participant: (1) had never used the needle exchange program as a source of needles, (2) had used the needle exchange program as the exclusive source of needles, and (3) had used the needle exchange program as one of several sources for obtaining needles. After controlling for multiple covariates in the logistic model (number of partners sharing equipment in previous month; number of times having used new injection equipment; number of acquaintances known to be HIV positive; booting; practicing disinfection; and drug of choice), the odds ratio (OR) associated with participants having used the needle exchange program as their exclusive source of needles in the last 6 months prior to seroconversion was found to be 5.19 (95 percent CI: 1.9 to 14.5). Those who did not make exclusive use of the needle exchange program as their source of needles were found to be 16.78 times more likely to seroconvert than needle exchange nonusers (i.e., OR = 16.78; 95 percent CI: 2.7 to 06.0).

Review

As with the other research discussed above, biases in parameter estimates due to the use of limited sampling strategies pose serious concerns for the generalizability of these findings either to the population of injection drug users or to the population of needle exchange program users in Montréal. One of the panel's concerns with this study is that the authors use causal language to describe the purpose of their analysis. In their abstract, Bruneau et al. (1995) state that they performed a series of analyses to assess the baseline determinants of HIV prevalence, entry determinants of HIV seroincidence, and follow-up determinants immediately preceding HIV seroconversion. The use of the term determinants would seem to indicate that these researchers are attempting to assess the causal effect of needle exchange participation on HIV prevalence and incidence. However, given the limitations of the study design and the analytical methods used, this study is incapable of sorting out the independent causal effects of each predictor on the outcome variables. It should be noted that, during a briefing session with the panel (Bruneau, 1995), the authors clearly communicated to us that they did not attempt to assess the causal effect of needle

exchange on seroprevalence or seroincidence. They consider their study to be purely descriptive in nature and not evaluative.

One difficulty associated with trying to assess needle exchange program effects on seroprevalence and seroincidence with these data relates to properly identifying and measuring confounding factors. The choice of variables for control is not well specified. This makes it extremely difficult to know whether the list of controls is relevant or complete enough to address the selectivity processes that might distinguish attenders from nonattenders. The measurement level of most variables is weak, consisting mostly of dichotomized or trichotomized variables, and this can significantly limit the capacity of the statistical adjustment process to adjust fully for the potential influence of those variables. Moreover, no attempt to assess the influence of interactions was discussed.

The key variable used in this study to assesses needle exchange program participation is limited, consisting of a single item asking respondents if they have used the needle exchange program at least once in the last 6 months. The use of a single item to categorize individuals as having participated in the needle exchange program raises concerns about measurement errors—mainly systematic errors in this case—in the variable being measured, which can produce serious biasing effects. Systematic measurement error refers to measurement validity. This type of error occurs when the true variable of interest has not been measured (e.g., time at risk while exposed to the needle exchange) and some other variable or proxy is used in its place (e.g., use of program at least once in last 6 months). When more than one covariate is used in the analysis, the effects of random and systematic errors become quite unpredictable and may overestimate or underestimate the regression coefficients.

Another noteworthy consideration is that injection drug users who do not use the needle exchange program in Montréal have access to sterile injection equipment through pharmacies (there is a pharmacy a block away from the exchange program that sells syringes and is open 24 hours a day). Furthermore, although the seroprevalence and seroincidence among needle exchange participants are higher than among nonparticipants, both groups have high rates of infection, although the nonexclusive needle exchange users were found to be at substantially higher risk than the exclusive users of the program.

Having access to sterile needles in Montréal through sources other than needle exchange is not problematic. It is clear that some selectivity processes are at work. Something is attracting high-risk injectors to the exchange program. Without a more detailed understanding of the characteristics that distinguish nonusers from users, we cannot ascribe the differences in the seroprevalence and seroincidence rates to the needle exchange program.

Again, we note that the authors themselves do not attribute the observed differences to the program.

CHICAGO

Investigators in Chicago have recently reported in two unpublished manuscripts the results of an investigation of the relationship among access to free needles through needle exchange program participation, drug-use behaviors (injection frequency, needle use, needle exchange use), other HIV risk behaviors, and HIV incidence to disentangle the causal effect of the Chicago needle exchange on these critical variables.

Demand for Free Needles and Their Effect on Injecting Frequency and Needle Use

In their first paper, O'Brien et al. (1995a) attempt to examine the causal effect of needle exchange use on individual needle and drug use. The Chicago needle exchange program was initiated in 1992. Before the program was initiated, these investigators had been monitoring trends in risk behaviors and HIV incidence among out-of-treatment injection drug users in an effort to assess the impact of an extensive outreach HIV intervention program (discussed in detail in Chapter 6). This study's participants are part of three distinct cohorts that were recruited from three different inner-city neighborhoods: the South Side (mostly African American), North Side (ethnically mixed), and Northwest Side (largely Puerto Rican). The three cohorts were recruited from these three neighborhoods by outreach workers in local community settings, such as street corners, copping areas, and shooting galleries.

The first cohort (1988 cohort) was assembled as part of a longitudinal outreach HIV prevention study and consisted of 850 injection drug users, of which 25 percent were found to be HIV positive at baseline. An additional cohort of 244 injection drug users (baseline HIV prevalence was 32 percent) not exposed to the outreach HIV prevention program was recruited in 1992 (1992 cohort) to supplement the original cohort. Finally, a third cohort of 323 injection drug users, also not exposed to the outreach HIV prevention program, was recruited in 1994 (1994 cohort) and found to have a 24 percent baseline HIV prevalence rate. Results of the analyses presented in this manuscript are based on demographic characteristics, drug-use risk behaviors, sexual risk behaviors, and HIV serology test results collected in 1994 as part of the baseline assessment for the 1994 cohort and as part of a 1994 follow-up assessment for the 1988 and 1992 cohorts for members that were still injecting (n = 728) at the time. They are also based on interview data (demographic characteristics and risk behaviors) and serologies

collected in a 1993 follow-up (n = 405) for the 1988 and 1992 cohorts.

Drug-use behavior measures included the number of injections for which participants had used their last needle, the total number of injections over the past 4 weeks, and the amount of money spent on drugs in the last week. From these, a measure of injection frequency per week was derived (number of injections over past 4 weeks/4) and a measure of needles used per week was constructed as a linear function of the number of injections per week and the number of times the participant's last needle was used (number of injections per week/number of times used last needle). Two measures of needle exchange use were obtained, a dichotomous measure (use/nonuse in past 4 weeks) and an extent of use measure (nonuse in last 6 months; used in the last 6 months but not in last 4 weeks; used at least once in last 6 months but at a current annual rate of less than 25 times a year; and used at a current rate of over 25 times per year). Needle exchange users were asked to report the number of needles they exchanged in the last 4 weeks; from this, a measure of extra needles per week was derived by taking the difference between the number of needles exchanged per week and the number of needles used per week. The street price of needles in the three areas was reported by the 1994 cohort, and the average was used to compute the value of needles used per week. A relative measure of perinjection cost of drugs was derived for each area and treated as an indicator of injecting drug prices. Other structured interview measures included the number of injection drug user associates and coinhabitants, various injecting and sexual HIV-related risk behaviors, the extent of self-reported frequency of worry about becoming infected with HIV via injection drug use, and having enough money.

A two-step approach was used to assess the effect of free needles on needle exchange participants' current drug use (drug expenditure and current injection frequency) and needle use (number of times a needle is used). First, predictors (potential explanatory variables) of needle exchange use, total needles exchanged, and extra needles were examined, while initially accounting for preexisting level of drug use (past injection frequency) by using 1988 and 1992 cohort data (n = 405). Then, 1994 data (n = 728) were used to predict the same three outcome measures, while ignoring the preexisting level of drug use (past injection frequency). The purpose of repeating the analyses without the preexisting level of drug use in the regression models was to examine the stability of the estimated coefficients of those predictors found to be significantly related to the outcome measures in the initial equations when the preexisting level of drug use was included as a covariate in the equations. That approach was needed because information pertaining to the preexisting level of drug use (past injection frequency)

TABLE A.4 Predictive Models of Chicago Needle Exchange Use, Number of Needles Exchanged, and Extra Needles

|

|

EQ1: Exchange Use [OR/(.95% CI)] |

EQ2: Total Needles Exchanged [β/(t statistic)] |

EQ3: Extra Needles [β/(t statistic)] |

|||

|

|

Panel |

All |

Panel |

All |

Panel |

All |

|

Intercept |

.011; (.01–0.9) |

.03; (.006–.12) |

8.2; (0.9) |

4.6; (0.68) |

3.9; (0.49) |

1.4; (0.2) |

|

Weekly needle expense (log) |

1.6; (1.4–1.9) |

1.7; (1.5–1.9) |

2.99; (6.17) |

4.17; (9.1) |

1.96; (4.1) |

2.6; (6.4) |

|

Prior level of injecting |

1.04; (1.02–1.07) |

— |

0.32; (3.59) |

— |

0.28; (3.47) |

— |

|

HIV status |

2.14; (1.26–3.6) |

1.14; (.79–1.6) |

2.85; (1.13) |

2.7; (1.46) |

1.59; (0.79) |

1.79; (1.1) |

|

Relative drug prices |

2.2; (.24–19.4) |

4.3; (1.9–9.6) |

11.28; (1.2) |

8.2; (2.0) |

10.6; (1.2) |

7.0; (1.94) |

|

Needle prices |

1.4; (.46–4.4) |

.88; (.69–1.1) |

-4.0; (-0.87) |

-1.9; (-1.49) |

-3.76; (-0.87) |

-1.54; (-1.36) |

|

Race: Puerto Rican |

1.57; (.7–3.4) |

1.37; (.89–2.1) |

2.3; (0.7) |

-.53; (-0.25) |

1.28; (0.42) |

-0.28; (-0.15) |

|

Race: white |

1.26; (.62–2.55) |

1.44; (.90–2.3) |

3.6; (1.2) |

1.11; (0.46) |

1.5; (0.54) |

-0.05; (-0.02) |

|

Age |

1.0; (.69–1.4) |

1.21; (.96–1.5) |

-0.95; (-0.6) |

0.39; (0.33) |

-0.48; (-0.35) |

0.71; (0.68) |

|

Worry about AIDS |

0.94; (.85–1.04) |

1.05; (.98–1.11) |

-0.6; (-1.5) |

-0.11; (-0.35) |

-0.47; (-1.3) |

-0.12; (-0.4) |

|

Worry about money |

1.0; (.9–1.1) |

1.01; (.94–1.08) |

-0.46; (-1.1) |

-0.54; (-1.56) |

-0.36; (-1.0) |

-0.39; (-1.2) |

|

1992 cohort |

0.8; 0.87(.4–1.5) |

1.22; (.7–2.1) |

-3.2; (1.29) |

-1.3; (-0.48) |

-2.45; (-1.0) |

–; (-0.3) |

|

1994 cohort |

— |

1.03; (.65–1.6) |

— |

2.58; (1.1) |

— |

2.6; (1.2) |

|

χ2 |

125 (df = 12); (p < .001) |

151 (df = 12); (p < .001) |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

Hosmer-Lemeshow Goodness-of-fit measure |

6.3; (p = .61) |

10; (p = .26) |

— |

— |

— |

— |

|

R2 |

— |

— |

.13 |

.16 |

.10 |

.076 |

|

SOURCE: From Needle Exchange in Chicago: The Demand for Free Needles and Their Effect on Injecting Frequency and Needle Use (O'Brien et al., 1995a: Table 3). |

||||||

was not available for a substantial portion of the 1994 data. Table A.4 summarizes the results of these analyses.

The results of the logistic regression of needle exchange use on potential explanatory variables show that only the ''weekly needle expense" variable

was found to be significant in both sets of equations (i.e., using the 1988 and 1992 cohorts while controlling for the preexisting level of drug use and with the entire set of 1994 data). Moreover, the estimated effect for weekly needle expense was the same in both equations, and the relative drug price became significant when complete data from the 1994 cohort were used.

Most variables used to predict total needles exchanged and extra needles were not found to be significantly related in the multivariate regression equation to these two outcome measures. Both weekly needle expense and relative drug prices were found to be associated with these two outcome measures.

The second step of the analyses called for using two-stage least-squares regressions to estimate the effects of free needles on drug expenditure, current injection frequency, and number of times a needle is used. If the coefficients for free needles (i.e., extra needles) could be found to be significantly different from zero, free needles were considered to have a causal effect on current level of drug use. Again, the 1988 and 1992 cohorts (n = 405) were first used to take into account the preexisting level of drug use to assess the causal effect of prior drug use levels on 1994 data (drug expenditure, current injection frequency, and number of times a needle is used).

Then, as was the case earlier, the two-stage least-squares regression equations were reexamined while making use of the entire 1994 data (n = 728) without including preexisting levels of drug use (past injection frequency) in the equations (i.e., once using only 1988 and 1992 follow-up data, and once using all 1994 data). As stated above, these latter sets of equations were carried out to examine the stability of the parameter estimates (coefficients). Furthermore, these equations were reestimated with the 1988 and 1992 cohorts using Maddala's formulation (using both needle exchange users and nonusers) of Heckman's method in an attempt to eliminate selection bias. Using this procedure, the effects of extra needles remained significant in each set of equations (i.e., for drug expenditure and current injection frequency).

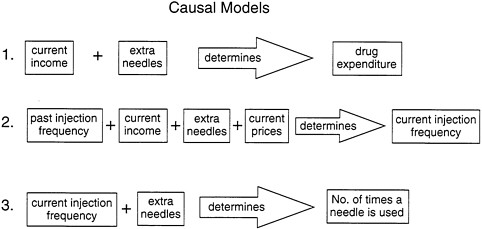

Although the authors did not specifically provide their predictive equations, the text can be interpreted as reflecting the following primary elements of the causal models (Figure A.1):

D=f(Y, X); (1)

J=g(Y, P, X, J') and (2)

N=(J, X) (3)

where: D = drug expenditure; Y = current income; X = number of extra needles; P = current price; J' = past injection frequency; J = current injection frequency; and N = number of times a needle is used.

Partial results of the two-stage least-squares regressions are depicted in

FIGURE A.1 Causal models proposed by O'Brien et al. (1995a)

Table A.5. The solution of the first equation regarding drug expenditure per week indicates that weekly drug expenditure increases as both weekly income and extra needles increase. This is true for the 1988 and 1992 cohorts, regardless of whether past injection frequency is included in the equation. Moreover, the results of the two-stage least-squares regressions, based on the 1994 data, show little variation in the magnitude of the extra needles effect in the subsamples of 405 panel members or in the entire sample of 728). The authors interpret this finding as showing that current cash income and current extra needles exchanged determine drug expenditure. They also state that the positive effect of extra needles exchanged on drug expenditures implies that exchangers spend more for drugs than can be expected from only their level of weekly cash income and in proportion to the number of extra needles.

The current injection frequency equations indicate that, when past injection frequency is incorporated into the model while using the 1988 and 1992 cohorts, the latter does not contribute to explaining variations in the current level of injection frequency. Estimated effects for the extra needles variable were found to be relatively stable when data from the 1988 and 1992 cohorts were used compared with fitting the model to the 1994 data. The investigators state that the positive coefficient of extra needles exchanged in the drug expenditure model and the positive effect of extra needles on current injection frequency indicate that extra free needles are increasing the frequency of drug injecting.

The last set of equations presented in Table A.5 pertains to the number of times a needle is used. The effect of the number of needles exchanged was not found to be significant in any of the regression equations, whereas

TABLE A.5 Chicago's Two-Stage Least-Squares Regression Resultsa

|

|

1988-1992 Cohortb |

1988-1992 Cohortc |

1994 Cohortc |

|

Drug expenditure |

|

|

|

|

Weekly income |

0.45 (6.9) |

0.45 (6.0) |

0.54 (9.4) |

|

Extra needles |

0.95 (4.4) |

1.2 (4.1) |

0.58 (3.1) |

|

R2 |

0.14 |

0.11 |

0.27 |

|

Current injection frequency |

|

|

|

|

Past injection frequency |

-0.20 (-1.1) |

— |

— |

|

Extra needles |

2.4 (4.0) |

2.3 (4.6) |

2.15 (4.8) |

|

Current drug price |

-0.12 (-0.9) |

-0.10 (-0.78) |

-0.21 (-1.6) |

|

R2 |

0.06 |

0.06 |

0.08 |

|

Injections per needle |

|

|

|

|

Current injection frequency |

-0.27 (-3.4) |

-0.27 (-1.4) |

-1.0 (-2.3) |

|

No. of needles exchanged |

-0.14 (-0.31) |

-0.14 (0.3) |

0.8 (0.9) |

|

R2 |

0.06 |

0.07 |

0.08 |

|

a Entries are standardized coefficients (asymptotic t statistics). b Past injection frequency (i.e., 1993 data) included. c Past injection frequency not included. SOURCE: Adapted from Needle Exchange in Chicago: The Demand for Free Needles and Their Effect on Injecting Frequency and Needle Use (O'Brien et al., 1995a:Table 4). |

|||

the effect of current injection frequency was found to be negative and significant. As current injection frequency increases, the number of times a needle is used decreases. The authors conclude that the lower number of times a needle is used among exchangers is not due to free needles, but rather to the higher level of current injection frequency among the exchangers.

These authors also compared their data with results of Kaplan's New Haven needle exchange evaluation findings (see Chapter 7 for a review of Kaplan's work). Using data from their 1994 cohort, the investigators regressed information reported by injection drug users regarding how long they keep a used needle on use of the exchange program, needles used per week, risky injecting, HIV status, handing off a used needle, and number of times a needle was used for injecting. The only significant predictor of how long a needle was kept was the number of times a needle was used. The authors interpreted this as showing that the use of a needle exchange did not affect the circulation time of needles as measured in their study. Moreover, to explore the potential effect of needle exchange programs in recapturing used needles (removing them from circulation), the authors regressed study participants' (1994 cohort) reported method for disposing of used needles (throwing away needles) on the same variables mentioned above. The only

variable found to be associated with throwing a needle away was handing off a used needle; needle exchange use was not found to reduce throwing away needles after use. This latter finding was interpreted by the authors as indicating that the utility of needle exchange in recapturing used needles is limited. Finally, researchers reported that exchange users do not report a significantly higher level of worry about HIV infection than nonusers.

Review

This research (O'Brien et al., 1995a) reported that needle exchange users injected more frequently than nonusers and, on average, obtained three times more than the number of needles that they were estimated to use personally. The estimates of drug expenditures and current injection frequency were positively associated with the number of needles exchanged. These authors infer that access to free needles results in increased drug expenditure and injection frequency among exchange users. Moreover, the effect of free needles (number of needles exchanged) on the number of times a needle is used was reported not to be related, while the current level of drug use (current injection frequency) was reported to be negatively related to the number of times a needle was used. This latter finding is interpreted as indicating that needle exchange participation (or access to free needles) does not impact the number of times a needle is used and that current injection frequency determines the number of times a needle is used.

Several concerns arise in assessing the soundness of the conclusions drawn by these investigators. The attempt to disentangle causal relationships on the basis of observational data has always been problematic and controversial, and the problems are considerably greater when the data are cross-sectional (as is the case here). There are numerous strategies possible (i.e., covariance analysis, structural equation models, and selection models); the strategy adopted by the Chicago research team was to use a two-stage least-squares (2SLS) procedure (i.e., a selection model) to estimate their equations. This procedure allows for estimating effects when one variable is both a dependent (response) variable and an independent (explanatory) variable. In addition, sample selection bias was investigated, using a procedure developed by Heckman (1979).

The panel's primary concerns relate to (1) the absence of any presentation or consideration of plausible alternative or competing models and (2) serious potential for bias in estimates due to measurement error.

With respect to alternative models, the Chicago researchers assert that current injection frequency is a function of prior injection frequency, current income, extra needles, and price. But one alternative model would assert that current income is a function of current injection frequency. That

is, the frequency with which a person injects drugs leads to the need for additional money and engaging in money-gathering activities (legal and otherwise). This very plausible alternative model would have major implications for the estimates derived from the model. The lack of consideration of this and other plausible alternative models renders the manuscript's conclusions far from compelling.

The 2SLS method is appropriate under fairly stringent conditions. In particular, in order to achieve identification of the parameters being estimated, there need to be "instrument" variables that are unrelated to the measured causes of the endogenous variables. In this particular application, the method is appropriate only if there are predictor variables presented in the manuscript's Table A.4 that should be excluded (based on a priori consideration) from the regressions in Table A.5. One problem is that there is no discussion in the manuscript about this issue, and another is that there may not be a plausible argument to be made. In this specific case, the manuscript does not present the actual equations estimated, making it difficult to determine which variables have been excluded on an a priori basis. Weekly needle expense may be one such variable, but it seems likely that this would have a direct effect on all dependent variables in Table A.5. Thus, in addition to the weakness of lack of consideration of plausible alternative models, the manuscript fails to provide adequate consideration of the assumptions underlying the particular model that was estimated.

O'Brien et al. (1995a) did attempt to eliminate selection bias in their estimation of coefficients. Nonetheless, it should be noted that "the potential uses of selection modeling in evaluation have generated considerable controversy. … At present there are divergent and strongly held opinions about the potential uses and misuses of these procedures" (Coyle et al., 1991:175). The Chicago researchers used the Heckman method, as described in Maddala (1983:Chapter 9). However, this procedure has some major difficulties. Indeed, in certain situations, Heckman-type selection models may not improve estimates in observational data (Little, 1985; Stolzenberg, and Relles, 1990; Winship and Mare, 1992). Moreover, the method requires that there exist measured variables in the data set that can predict—in this specific case—the use (versus nonuse) of a needle exchange program. To the extent that needle exchange use is not well predicted, then the selection model may have little effect on parameter estimates.

Additional concerns are related to problems with measurement properties of some key variables. Although the reliability of the measures is not discussed, it may have important implications. For example, the effect of prior injecting is not significant in the panel sample predicting current injecting frequency in the 2SLS. But the 2SLS method assumes that these variables are measured without error (as does the ordinary least squares method—OLS). In fact, there is likely to be considerable measurement

error in these variables, and thus the "true" correlation or covariation between them may be substantially attenuated. The lack of fully controlling for the effect of prior injecting may lead to an overestimate of the effect of extra needles. These sorts of issues are always present in regression models. Modern structural equation models involving latent variables usually attempt to address them, though not necessarily successfully. But particularly when one method (OLS) shows a nonsignificant effect of extra needles on current injecting frequency, and another method (2SLS) shows a significant effect, caution in drawing causal conclusions should be stressed.

Another measurement issue is that no detailed information on the properties of the distribution of variables (e.g., variance, skewness) is provided. The authors report mean measures, some of which have large standard errors, which seem to indicate the possible presence of outliers; these, in turn, may have substantial impact on the reported results. For example, data reported in the manuscript are inconsistent with records maintained by the Chicago needle exchange program. That is, the exchange records show a mean of 15 needles obtained per week by exchangers compared with a mean of 30 per week (with a standard error of 37) reported by these authors. When comparing actual records with self-report data (as used by these investigators), it is to be expected that some disparity will be observed, but the magnitude of these disparities is of concern. The Chicago needle exchange records also show that the distribution of needles obtained per week is highly skewed, and that the median of 8 needles per week would be a better measure of central tendency than the mean. Another measurement concern relates to their extra needles measure. It does not allow for passing needles to other injectors who are not cohabitants and/or sharing partners.

With regard to systematic error, several of the measures used appear to be problematic. For example, the measure of worry about HIV was assessed after study participants had joined the needle exchange program (i.e., they may no longer worry as a result of having joined the program). Therefore, it is not surprising to find that such a measure was not related to needle exchange use.

Another source of concern is the representativeness of the sample of study participants of the population of needle exchange users and nonusers. The authors state that needle exchange users in their cohorts represent 20 percent of the total population of needle exchange users. But the critical issue that must be addressed is where these 20 percent fall on the distribution of the critical variables used in the model: if they are extreme cases, it may bias the reported estimates. Again, data from the Chicago needle exchange records show a median of one visit per month, with 75 percent visiting two or fewer times per month—compared with the 50 percent visiting weekly or more frequently in the self-report data used by the authors. It appears that these investigators are attempting to test the tenability of an

aggregate model to explain the behaviors of needle exchange users and nonusers without giving appropriate attention to the potentially biasing effect of outliers in their data set.

Another design concern relates to the investigators' assumption that needle exchange nonusers are not gaining access to needle exchange needles. If a large number of nonusers is obtaining sterile needles that have originated from the exchange programs, it could be argued that they are indirectly participating in the needle exchange program or at least benefiting from it.

The method used to verify the stability of coefficients also poses some difficulties. The paper indicates that the final equations that use the data from all cohorts (n = 728) also incorporate the 1988 and 1992 cohorts (n = 405) on which the original coefficients were derived. This nonindependence of samples raises questions about the ability of this approach to reliably assess the stability of coefficient estimates across samples (especially because more than half of the final sample were members of the original sample).

It is inappropriate for the investigators to apply the circulation theory concept used in the New Haven evaluation study. The Chicago program is not a one-for-one program, and the protocol it follows allows for the number of distributed needles to exceed the number of returned needles by 5 on a per-visit basis. Kaplan's circulation theory requires that needles be exchanged on a one-for-one basis; as derived in Kaplan's work, it is this law of conservation of needles that provides the link between needle exchange rates and the level of infection in needles. In the absence of a one-for-one exchange, there is no physical guarantee that needle circulation times will decline as the numbers of needles distributed increases, because there is a net increase in the total number of needles in circulation.

In sum, based on the panel's interpretation, we cannot say that the data justify the conclusions the researchers have reached.

Effects of Exchange Use on HIV Risk Behavior and Incidence

In a second paper, the same investigators (O'Brien et al., 1995b) explore the potential effect of needle exchange programs on HIV risk behaviors and incidence. Data from the 1994 interview and HIV serology test results of current injection drug users from all three cohorts (n = 728; 1988, 1992, and 1994 data), as well as data from the 1993 follow-up of the 1988 and 1992 cohorts (n = 405) described above, form the basis of the reported analyses.

Four measures of injection risk behaviors were derived. A dichotomous variable indicating overall risky injecting behavior based on injection drug users' reported use of others' used needles, consistent use of bleach,

sharing cotton, cookers, or water, and backloading (see Wiebel, 1990, for a description of the measure). Two additional dichotomous drug-related variables were constructed, one based exclusively on whether the injection drug user used other injection drug users' needles without using bleach and the other based on whether drug users passed their own used needles to other injectors. A final syringe-sharing variable consistent with Watters et al. (1994)—injecting risk behavior—was derived. This latter variable is based on information concerning an injector's use of someone else's needle and ignores possible cleaning practice with bleach. The sexual risk behavior variable assessed whether a respondent had multiple sex partners in the past 6 months or an injection drug user sex partner and did not always use a condom.

Three measures of needle exchange were derived: dichotomous use/nonuse in the past 4 weeks; use over two interview waves; and a four-category measure of frequency of use similar to the Watters et al. (1994) measure. Other information collected during the follow-up and baseline interviews included: number of injection drug users' associates and cohabitants; frequency of worry about becoming infected with HIV via injection drug use; and having enough money.

Of the overall 1994 data (n = 728), 8 percent used the needle exchange once in the previous 4 weeks; 12 percent used it 2 to 3 times; and 19 percent used it once a week or more. This represents 40 percent (n = 285) of the total sample having used the exchange in the past 4 weeks, which also represents approximately 21 percent of all injection drug users who had used the program at least once since February 1, 1994.

With respect to HIV risk behaviors assessed in 1994, a comparison of needle exchange users and nonusers revealed no statistically significant difference in the proportion of study participants reporting having engaged in injection drug use risk behaviors, whereas nonusers were found to be more likely to report multiple sex risk (43 compared with 40 percent). The investigators used logistic regressions to examine the effect of exchange use on each risk behavior when prior level of risk was accounted for (using 1993 follow-up data on the 1988 and 1992 cohorts; n = 405). The results showed that the measure of prior risk behavior was the only significant predictor of current risk level; the main effect of needle exchange use, as well as its interaction with age, was nonsignificant for all risk variables. Moreover, these logistic regressions were reexamined using the 1994 data as a cross section, ignoring prior risk behavior, and the results showed that each risk variable was unaffected by frequency of exchange use.

There were 258 current injection drug users from the 1988 and 1992 cohorts known to be at risk of seroconverting at the 1994 follow-up. An equal proportion of these HIV-negative study participants were needle exchange users and nonusers. Three seroconverted over an average 9-month

observation period. Of the 177 who did not use the needle exchange, 1 person seroconverted in the same period (0.56 percent or 0.75 per 100 person years); of the 81 who had used the needle exchange, 2 seroconverted (2.50 percent or 3.0 per 100 person years). This difference in incidence is not statistically significant.

Review

The reported findings from this second paper by O'Brien and colleagues suggest that the needle exchange program has no protective effect on the risk behaviors and HIV infection rates among program participants. This research suffers from the same selectivity problems associated with the Chicago paper reviewed above. That is, there are problems with measurement error, and underadjustments originating from the unreliability of the measures used may explain, at least in part, the lack of effects. The control conditions (i.e., nonusers of the program) are sufficiently different as to render them unusable as a counterfactual condition.

Moreover, no observed reduction in risk behavior may be explained by the fact that a substantial proportion of the studied sample (i.e., the 1988 cohort) was exposed to an extensive HIV prevention program. Findings from that original study have shown significant declines in injection drug use risk behaviors (see Chapter 6).

The reported null results for program effect on HIV incidence are not surprising given the small number of years at risk chosen and the low power associated with the inferential test used. These findings do not prove that the needle exchange program has no protective effect on the rate of new HIV infections among needle exchange participants. That is, not being able to reject the null hypothesis (i.e., rates of HIV incidence in exchange users and nonusers are equal) does not establish that the null hypothesis is true (i.e., incidence rates are the same in both groups).

CONCLUSION

The study designs and analytical methods employed in the San Francisco, Montréal, and Chicago studies preclude making causal inferences about the effect of needle exchange programs on risk behaviors and HIV prevalence or incidence. In addition, none of these studies has used adequate sampling strategies to ensure that risk behavior and HIV prevalence and incidence estimates are representative of the injection drug-using populations who use and do not use the respective exchange programs. Nonetheless, the studies have reported measures of associations—although there is some question about the populations to which they apply—that are sizable and should be further studied with proper study designs, measurement, and

analytical methods to properly investigate the tenability of such causal relationships.

REFERENCES

Brookmeyer, R., and M.H. Gail 1994 AIDS Epidemiology: A Quantitative Approach. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Bruneau, J. 1995 Presentation at a meeting of the Panel on Needle Exchange and Bleach Distribution Programs, Washington, DC, April 5.

Bruneau, J., F. Lamothe, E. Franco, N. Lachance, J. Vincelette, and J. Soto 1995 Needle Exchange Program (NEP) Attendance and HIV-1 Infection in Montréal: Report of a Paradoxical Association. Abstract for International Conference on the Reduction of Drug Related Harm, Palazzo dei Congressi, Florence, Italy, March 26-30.

Coyle, S.L., R.F. Boruch, and C.F. Turner, eds. 1991 Evaluating AIDS Prevention Programs: Expanded Edition. Panel on the Evaluation of AIDS Interventions, National Research Council. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Hahn, J.A., K. Vranizan, and A.R. Moss 1995 Needle Exchange Among Injection Drug Users in San Francisco. Draft manuscript.

Hankins, C. 1994 Appendix E in The Proceedings of the Meeting on HIV Infection Among Injection Drug Users in Canada, Montréal, Québec, December 12-13.

Hankins, C., S. Gendron, J. Bruneau, F. Rouah, N. Paquette, M. Jalbert, F. Prévost, and B. Gomez 1992 Consumer Awareness, Utilization, and Satisfaction with CACTUS-Montréal's Needle Exchange. Eighth International Conference on AIDS, Amsterdam, July 19-24.

Hankins, C., S. Gendron, F. Rouah, C. Godbout, I. Mayr, and D. Lepine 1993 Rising Prevalence? Declining Incidence? Montréal's Needle Exchange: A Successful Verdict or Is the Jury Still Out? IXth International Conference on AIDS, Berlin, June 6-11.

Hankins, C., S. Gendron, J. Bruneau, and E. Roy 1994 Evaluating Montréal's needle exchange CACTUS-Montréal. Pp. 83-90 in Proceedings, Workshop on Needle Exchange and Bleach Distribution Programs. National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Heckman, J.J. 1979 Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 47:153-161.

Lamothe, F., J. Bruneau, J. Soto, N. Lachance, E. Franco, J. Vincelette, and M. Fauvel 1995 Risk Factors for HIV Seroconversion Among Injecting Drug Users in Montréal: The Saint-Luc Cohort Experience . Abstract number 074C. Tenth Annual International Conference on AIDS, Yokohama, Japan.

Little, R.J.A. 1985 A note about models for selectivity bias. Econometrica 53:1469-1474.

Moss, A. 1995 Presentation at a meeting of the Panel on Needle Exchange and Bleach Distribution Programs, Washington, DC, April 5.

O'Brien, M.U., J. Murray, F. Cannarozzi, A. Jimenez, W. Johnson, L. Ouellet, and W. Wiebel 1995a Needle Exchange in Chicago: The Demand for Free Needles and Their Effect on Injecting Frequency and Needle Use. Draft manuscript.

1995b Needle Exchange in Chicago: The Effects of Exchange Use on HIV Risk Behavior and Incidence. Draft manuscript.

Stolzenberg, R.M., and D.A. Relles 1990 Theory testing in a world of constrained research design: The significance of Heckman's censored sampling bias correction for nonexperimental research. Sociological Methods and Research 18:395-415.

Watters, J.K., M.J. Estilo, G.L. Clark, and J. Lorvick 1994 Syringe and needle exchange as HIV/AIDS prevention for injecting drug users. Journal of the American Medical Association 271(2):115-120.

Wiebel, W.W. 1990 Identifying and gaining access to hidden populations. Pp. 4-11 in E.Y. Lambert and W.W. Wiebel, eds., Collection and Interpretation of Data in Hidden Populations. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Winship, C., and R.D. Mare 1992 Models for sample selection bias. Annual Review of Sociology 18:327-350.