4 Community Views

In the evaluation of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs, one dimension involves scientific evidence on whether the behavior of injection drug users changes and rates of new infection are reduced. However, these issues cannot be viewed in isolation, because injection drug users inhabit communities that are affected by and have already developed responses to the behavior and consequences of drug abuse. Whether HIV prevention programs, such as needle exchanges, are established and what forms they take are shaped by multiple forces in the community. The sheer variety among the operational characteristics of needle exchange programs described in the previous chapter is to some extent a function of local

Note: Some of the information used in this chapter is from a paper prepared for the panel by Stephen Thomas and Sandra Crouse Quinn, Community Response to the Implementation of Needle Exchange and Bleach Distribution Programs (1994). Their paper discusses the primary historical, social, and political factors that have shaped community responses to the implementation of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs. It also presents results from cross-sectional surveys of selected African American populations to demonstrate how deficits in AIDS knowledge and attitudinal barriers have shaped the perceptions of African Americans toward needle exchange programs as an HIV prevention strategy advocated by public health authorities. In addition, some of the discussion is based on information from another paper prepared for the panel by David Metzger and Dominick DePhilippis, Treatment Community Views on Needle Exchange and Bleach Distribution Programs (1994). Their paper explores the basis for the dilemma faced by the large and diverse drug treatment community regarding the public debate and political controversy surrounding the brief and turbulent history of needle exchange programs in this country.

responses to such programs. The community is not some monolith; rather, it is a dynamic interaction of groups whose views and actions vary with location and time.

The panel undertook a wide range of activities to gather pertinent information about the views of various groups on the issues relating to the implementation of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs. We reviewed the literature systematically to gather the range and extent of opinions for two groups in which the expression of viewpoints has been extensive: the African American community and the treatment community. In fact, a special workshop was held, to which representatives of the community groups covered in this chapter were invited. The panel members conducted site visits to Chicago and San Francisco to discuss issues with community outreach workers. We also solicited information from pertinent professional organizations to identify formal positions on needle exchange and bleach distribution programs. Finally, a number of public opinion surveys were identified and reviewed.

In this report, we embrace a broad definition of community, which includes ethnic groups, business and religious organizations, government bodies, and professional groups. Understandably, the information presented in this chapter focuses primarily on those who have been most vocal in expressing their concerns about needle and bleach distribution programs. Other views have not been overlooked intentionally.

The chapter begins with a brief consideration of the moral and ethical arguments that come into play in these issues. We then discuss public opinion polls, which are informative to broadly gauge community attitudes toward needle exchange and bleach distribution programs over time. The chapter goes on to discuss the perspectives of a number of community groups and their responses to needle exchange and bleach distribution programs:

-

minority communities, which are disproportionately affected by drug abuse,

-

law enforcement officials, who are sworn to enforce laws,

-

pharmacists, who hold supplies of sterile needles, and

-

drug abuse treatment providers, who work with limited funding to impact the difficult processes of addiction.

The material presented in this chapter contributes to the panel's overall assessment of the effectiveness of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs, and its findings and conclusions are integrated in the recommendations that appear in Chapter 7. As stated in the Introduction, this approach reflects the development of the panel's deliberations on the issues.

MORAL/ETHICAL ARGUMENTS

The moral arguments that are a common theme of community groups concerned with needle exchange and bleach distribution programs also appear in federal policy statements. A critique of the New Haven needle exchange evaluation study by the Office of National Drug Control Policy illustrates this point (1992:1): "There is no getting around the fact that distributing needles facilitates drug use and undercuts the credibility of society's message that using drugs is illegal and morally wrong."

Ideological and moral concerns are not scientific, empirically based arguments; however, this in no way dilutes their importance. Needle exchange and bleach distribution programs can be established only within the context of communities, and their success or failure is highly dependent on the support and leadership of community members. The strength of the scientific arguments and their weight relative to the ethical case for or against these programs can be and have been debated at length by ethicists and other concerned individuals.

Although it is beyond the scope and expertise of the panel to fully examine the complex range of ethical issues that might be judged relevant to analyze the establishment of public health policies, we nonetheless present two fundamentally divergent views that may contribute to an understanding of the polarization encountered when the establishment of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs is considered.

Within the context of an ethical debate, whether needle exchange and bleach distribution programs contribute to increased drug use in society constitutes one of many harms and/or benefits that must be weighed relative to others (Pellegrino, 1990; O'Brien, 1989). Weighing the relative benefit and relative harm associated with an action before making a judgment about its ethical soundness has been called the proportionalist approach to ethical analysis (Fuller, 1993). Using this approach, one can argue that people are morally compelled to support a lesser harm (evil) in order to prevent a greater harm. From this perspective, the most convincing argument in favor of needle exchange programs lies in their claim as a significant strategy for reducing harm.

Two ethical traditions take the proportionalist approach. In Jewish medical ethics, the principle of pkuach nfesh mandates the protection of human life and holds that, when a life is at stake, all prohibitions contained in the Torah and the Talmud may be waived to save that life (Jakobovits, 1959). The other ethical tradition that supports the proportionalist position is the moral theology of Alphonsi Mariae de Ligorio (1907), which argues that it is ethical to support a less evil activity in order to prevent a more evil one. In the case of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs, according to this tradition, even if some empirically demonstrated harms

were associated with program implementation, it would still not necessarily be ruled out on ethical grounds.

A fundamentally different approach to ethical analysis is the deontologist approach. In this approach, actions are taken because they are right within themselves, not necessarily because some good will ensue. Accordingly, if one has concluded that injection drug use is immoral, then one may not ethically cooperate in any way with this behavior. Needle exchange programs would be viewed as immoral because they provide the material means for an immoral activity and therefore share in the evil of that activity.

Given these examples of two fundamentally divergent views of what is ethically acceptable, it is not surprising that there has been and continues to be substantial public discourse about the distribution of needles, syringes, and bleach. Nonetheless, both the public health and community well-being are at stake until we find common ground on which to clarify objectives and establish appropriate ways to reduce the spread of HIV, which may include the establishment of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs. As noted by O'Brien (1989), there is value in developing common definitions and mutually agreed-on ethical standards of analysis. Until such standards are set forth, it will be difficult to engage in a constructive ethical debate.

PUBLIC OPINION POLLS

A thorough review of public opinion polls conducted between 1985 and 1991 indicates that half of the general public supports harm reduction efforts that include needle cleaning, legalizing needle sales, needle exchange, and needle distribution (Lurie et al., 1993). Approval has tended to be higher for programs that combine bleach distribution and needle exchange than for programs that focus on needle distribution (Table 4.1). More important, the available evidence indicates that this support has tended to increase over time, as the issues have been publicly debated and more programs have been implemented.

For example, the Gilmore study (Table 4.1, Panel A) showed an increase in approval between 1988 and 1991 for teaching people to use bleach. In the same interval, that study showed an increase in support for legalizing the sale of needles and syringes to drug users (Panel B), and a similar rise in approval for needle exchange (Panel C). The studies in these three panels show substantial, sometimes majority support for measures that make sterile needles more available to injection drug users. With regard to the distribution of free sterile needles to injection drug users in order to retard the spread of AIDS (Panel D), again, between 1985 and 1991 across various locations, substantial support was found, although less than a majority in each opinion study.

As another illustration, the results of a 1994 household survey showed a

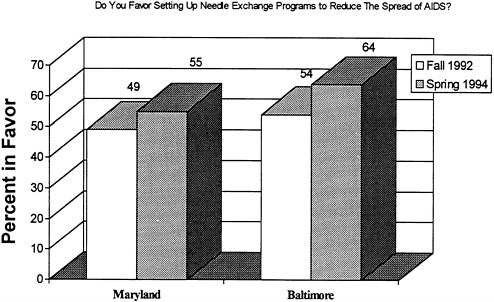

12 percent increase in the proportion of Maryland residents who support needle exchange programs (Figure 4.1). These results also point to a larger increase (19 percent) in the city of Baltimore than in the state as a whole. Moreover, findings from a recent nationwide telephone survey undertaken in February 1994 showed that, among the 1,001 adults sampled, 55 percent favored implementing needle exchange programs to reduce the spread of diseases such as AIDS, 37 percent favored allowing drug users to buy sterile needles without prescriptions from pharmacies, and 40 percent favored removing criminal penalties for the simple possession of needles and syringes (Hart, 1994).

We turn now to discussion of the views of particular groups in communities across the nation.

AFRICAN AMERICAN VIEWS

Much of the voiced African American opposition to needle exchange and bleach distribution programs must be understood in the context of perceptions that historically there has been government negligence in response to the drug abuse epidemic, distrust of public health authorities, and fear—and, for some, the conviction—that the broader society considers large segments of the African American population expendable (Thomas and Quinn, 1991, 1993). Pervasive throughout the African American community are uncertainties about the motivations of what they perceive as the white establishment.

This underlying distrust is grounded in part in a history of medical neglect and significant violations of human subjects. Most specifically, the legacy of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study is a vivid reminder (Thomas and Quinn, 1991). This study, conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service from 1932 to 1972, deliberately and irresponsibly withheld treatment for syphilis from an African American community in Tuskegee, Alabama. The Tuskegee study continues to serve as the basis for much of the widespread distrust of public health and government authorities (Jones, 1981). Recently confirmed reports about other government abuses (e.g., radiation experiments, cocaine distribution) are portrayed as further evidence to support suspicions and fears about the motivation and intent of officials urging the utilization of needle exchange programs.

According to Thomas and others (Thomas and Quinn, 1993; Belgrave and Randolph, 1993), many African Americans, including many who are well educated, believe that HIV is manufactured and that drugs are being deliberately supplied to African American communities. The prevalence of AIDS itself, as well as programs purported to reduce its spread, are viewed as part of a larger genocidal conspiracy against African Americans. In a 1990 survey of the views of African American churchgoers in five cities—Atlanta,

TABLE 4.1 Results of U. S. Public Opinion Polls on Needle Exchange and Needle Cleaning, 1985-1991

|

Date of Survey |

Description of Respondents |

Polling Institution |

Question |

Results |

|

A. NEEDLE CLEANING |

||||

|

April/May 1988 |

Washington State; n = 800 |

Gilmore Research for Washington State HIV/AIDS; General Population Survey (Olympia, WA) (Washington State Department of Health, 1991) |

Would you support a program to teach people how to clean needles with bleach? |

59%—Yes; 41%—No/don't know |

|

May 1989 |

Utah; n = 849 |

Survey Research Center, University of Utah (Salt Lake City, UT) (University of Utah, 1989) |

Free needle cleaning kits should be available for IV drug users: agree or disagree? |

43%—Agree; 57%—Disagree/don't know |

|

April/May 1991 |

Washington State; n = 801 |

Gilmore Research for Washington State HIV/AIDS General Population Survey (Olympia, WA) (Washington State Department of Health, 1991) |

Would you support a program to teach people how to clean needles with bleach? |

65%—Yes; 35%—No/don't know |

|

Date of Survey |

Description of Respondents |

Polling Institution |

Question |

Results |

|

B. REMOVAL OF LEGAL BARRIERS TO NEEDLE PURCHASE |

||||

|

April/May 1988 |

Washington State; n = 800 |

Gilmore Research for Washington State HIV/AIDS General Population Survey (Olympia, WA) (Washington State Department of Health, 1991) |

Would you support making needles and syringes legal to sell to drug users? |

38%—Yes; 62%—No/don't know |

|

April/May 1991 |

Washington State; n = 801 |

Gilmore Research for Washington State HIV/AIDS General Population Survey (Olympia, WA) (Washington State Department of Health, 1991) |

Would you support making needles and syringes legal to sell to drug users? |

45%—Yes; 55%—No/don't know |

|

Date of Survey |

Description of Respondents |

Polling Institution |

Question |

Results |

|

C. NEEDLE EXCHANGE |

||||

|

April/May 1988 |

Washington State; n = 800 |

Gilmore Research for Washington State HIV/AIDS General Population Survey (Olympia, WA) (Washington State Department of Health, 1991) |

Would you support a needle exchange program where a drug user could obtain a free sterile needle in exchange for a used one? |

55%—Yes; 45%—No/don't know |

|

January 1989 |

Pierce and South King Counties, WA; n = 411 |

Tacoma Morning News Tribune Poll conducted by Tacoma Marketing Research (Tacoma, WA) (Eskenazi, 1989) |

Do you agree with the Board of Health decision to fund a hypodermic needle exchange program designed to reduce the spread of AIDS? |

67%—Agree; 18%—Disagree; 14%—Unsure/don't know |

|

1989/1990 |

New York City, NY; Members of Harlem families; n = 326 |

Ann Brunswick Columbia University (New York City, NY) (Brunswick, 1991) |

Some people have suggested that handing out clean needles, free, would be a good way to reduce AIDS among intravenous drug users.; Other people say that providing free needles would encourage drug use. How do you personally feel about allowing drug users to exchange their used needles for clean ones? |

38%—Agree strongly; 16%—Agree somewhat; 35%—Disagree strongly; 5%—Disagree somewhat; 6%—Not sure |

|

Date of Survey |

Description of Respondents |

Polling Institution |

Questions |

Results |

|

1989/1990 |

New York City, NY; Injection drug users in Harlem families; n = 38 |

Ann Brunswick Columbia University (New York City, NY) (Brunswick, 1991) |

Some people have suggested that handing out clean needles, free, would be a good way to reduce AIDS among intravenous drug users.; Other people say that providing free needles would encourage drug use. How do you personally feel about allowing drug users to exchange their used needles for clean ones? |

53%—Agree strongly; 19%—Agree somewhat; 18%—Disagree strongly; 6%—Disagree somewhat; 4%—Not sure |

|

April/May 1991 |

Washington State; n = 801 |

Gilmore Research for Washington State HIV/AIDS General Population Survey (Olympia, WA) (Washington State Department of Health, 1991) |

Would you support a needle exchange program where a drug user could obtain a free sterile needle in exchange for a used one? |

68%—Yes; 32% —No/don't know |

|

Date of Survey |

Description of Respondents |

Polling Institution |

Question |

Results |

|

D. NEEDLE DISTRIBUTION |

||||

|

November 1985 |

Maryland residents who indicated they had heard about AIDS in the news recently; n = 1,074 |

Hollander, Cohen, McBride associates for the Maryland Department of Health (Baltimore, MD) (Hollander et al., 1985) |

One of the ways AIDS is spread is by drug abusers who share needles. Some health authorities have suggested that clean needles be provided free to those who ask for them [to] control spreading the disease that way. Do you agree with this approach? |

37%—Agree; 55%—Disagree; 0%—Depends; 8%—Don't know; 0%—Not applicable |

|

March 1987 |

Connecticut; n = 500 |

The Roper Center for Public Opinion Research (Storrs, CT) (1987) |

Do you favor or oppose distributing free sterile needles to drug users to slow the spread of AIDS through contaminated needles? |

33%—Favor; 60%—Oppose; 7%—Don't know |

|

October 1988 |

U.S.; n = 1,606 |

CBS News/New York Times Poll (New York City, NY) |

Would you favor or oppose giving injection drug users sterilized needles for free if it would slow down the spread of AIDS? |

40%—Favor; 53%—Oppose; 7%—Don't know |

|

Date of Survey |

Description of Respondents |

Polling Institution |

Questions |

Results |

|

February 1989 |

New York City, NY; n = 1,015 |

Newsday (New York City, NY) (1989) |

Do you approve or disapprove of the city's programs to provide clean needles to drug users in order to prevent the spread of AIDS? |

50%—Approve; 40%—Disapprove; 10%—Don't know |

|

May 1989 |

Utah; n = 849 |

Survey Research Center, University of Utah (Salt Lake City, UT) (University of Utah, 1989) |

Free needles and syringes should be made available to intravenous drug addicts: agree or disagree? |

38%—Agree; 62%—Disagree/don't know |

|

May 1989 |

Connecticut; n = 768 |

Northeast Research (Orono, ME) (1989) |

I'm going to read a few of the things people have suggested that might help stop the spread of AIDS in CT. For each one please tell me if you think that method should be used. You can answer yes or no, or that you have no opinion about it. Give out free needles to drug dealers. |

40%—Yes; 47%—No; 13%—Don't know |

|

May 1989 |

United States; n = 1,054 |

Media General/Associated Press (Richmond, VA) (1989) |

The AIDS virus can be transmitted when people who use drugs share needles. If giving intravenous drug abusers free needles would slow down the spread of AIDS, would you favor or oppose giving addicts sterilized needles for free? |

50%—Favor; 43%—Oppose; 7%—Don't know |

|

Date of Survey |

Description of Respondents |

Polling Institution |

Question |

Results |

|

October 1989 |

Maricopa County, AZ; n = 809 |

Arizona Republic (Phoenix, AZ) (The Arizona Republic, 1993) |

Would you favor or oppose a program that would make it possible for sterilized needles to be distributed to drug addicts as a way to slow the spread of the AIDS virus? |

52%—Favor; 45%—Oppose; 3%—Don't know |

|

January 1990 |

Massachusetts registered voters; n = 405 |

Bannon Research (Boston, MA) (1990) |

Do you strongly favor, mildly favor, mildly oppose, or strongly oppose giving clean needles to drug users so they don't spread the AIDS virus? |

26%—Strongly favor; 26%—Mildly favor; 14%—Mildly oppose; 31%—Strongly oppose; 3%—Don't know/no answer |

|

February 1990 |

Chicago, IL; n = 449 |

Northwestern University Survey Laboratory (Evanston, IL) (Lavrakas, 1990) |

Drug treatment centers should distribute free needles to intravenous drug users to reduce the chances of spreading AIDS: strongly agree, somewhat agree, somewhat disagree, or strongly disagree? |

38%—Strongly agree; 19%—Somewhat agree; 10%—Somewhat disagree; 29%—Strongly disagree; 4%—Uncertain |

|

Spring 1991 |

Black church congregation members in 5 cities; Before: n = 202 After: n = 180 |

Minority Health Research Laboratory, University of Maryland for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (Atlanta, GA) (Thomas and Quinn, 1993b) |

Survey participants were asked the same questions before and after a training session on AIDS issues The question asked respondents to agree or disagree with the following statement: I would support laws to pass out free clean needles to people who shoot drugs. |

Before; 40%—Agree; 41%—Disagree; 19%—Unsure; After; 47%—Agree; 40%—Disagree; 14%—Unsure |

|

Date of Survey |

Description of Respondents |

Polling Institution |

Question |

Results |

|

May 1991 |

Arizona; n = 808 |

Arizona Republic (Phoenix, AZ) (The Arizona Republic, 1993) |

Do you agree or disagree with each of the following statements about AIDS? The state should give away needles to drug addicts to prevent the spread of AIDS. |

26%—Agree; 73%—Disagree; 1%—Don't know |

|

June 1991 |

Denver, CO; n = 303 |

Talmey-Drake Research Strategy, Inc., for the Denver Post/KCNC TV (Denver, CO) (1991) |

Please state your opinion regarding the following statement: The city of Denver should provide clean hypodermic needles to drug addicts to help stop the spread of AIDS. |

25%—Strongly agree; 24%—Somewhat agree; 16%—Somewhat disagree; 25%—Strongly disagree; 10%—Uncertain |

|

SOURCE: The Public Health Impact of Needle Exchange Programs in the United States and Abroad. Volume 1 (Lurie et al., 1993:330-332). |

||||

FIGURE 4.1 Needle exchange support in the state of Maryland and Baltimore city.

SOURCE: Center for Substance Abuse Research (1994).

Georgia; Charlotte, North Carolina; Detroit, Michigan; Kansas City, Missouri; and Tuscaloosa, Alabama—Thomas and Quinn (1993) found that only one in five persons trusts government reports on AIDS and that two-thirds consider the possibility that AIDS is a form of genocide. The study also found that 38 percent of African American college students in Washington, D.C., believe ''there is some truth in reports that the AIDS virus was produced in a germ warfare laboratory"; another 26 percent said they were "unsure." Major journals focusing on issues of concern to African Americans, for example, Essence (Bates, 1990), have given wide attention, and therefore some degree of sanction, to these beliefs. Although these results cannot be generalized to all African Americans, they are a disturbing revelation to many who are attempting to conduct HIV and AIDS health promotion and disease prevention activities within these communities.

Proponents of genocidal theories also argue that it is not by chance that alcohol and drug abuse plague African American communities. It is pointed out that retail outlets for the sale of alcohol are controlled by government policy. The Reverend Graylan Ellis-Hagler of Plymouth Congregational Church in Washington, D.C., sounds a common theme heard in this community (Ellis-Hagler, 1993, as cited in Thomas and Quinn, 1994):

Drugs are not in our community by coincidence, but by [design]. Just like you can find a liquor store on every corner [in the inner city], you can find a dope house on every street and it's not there by coincidence, it is there by [design].

Similarly, news from sources such as 60 Minutes (cited in Thomas and Quinn, 1994) and The New York Times (Weiner, 1993) is presented as evidence that illegal drugs are not in the community by coincidence. The New York Times reported that the Central Intelligence Agency's antidrug program in Venezuela used public monies to ship a ton of cocaine to the United States and allowed it to be sold on the streets. No criminal charges were brought in the case, and the government officials responsible declared the matter a "most regrettable incident." Many African Americans and Latinos declared it to be "genocide" (Weiner, 1993).

Church leaders and elected officials have been the primary sources of expressed opposition by the African American community to needle exchange and bleach distribution programs. The church is a central and important influence in the African American community, and its moral teachings generally forbid the kind of sexual and drug-use behaviors that are associated with the transmission of HIV and AIDS. Much of the initial opposition of the African American clergy to the idea of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs focused on the immorality of the underlying risk behaviors. Certain high-profile and prominent clergy in the African American community have joined forces with politicians, business executives, and health care providers who have determined that these interventions represent a grave risk to the community.

Influenced by the historical legacy described above, these opponents have described the idea of making sterile needles available to drug users as misguided and dangerous. Politicians and public health officials are accused of irresponsibility in their failure to concentrate exclusively on increasing funding and programs for comprehensive drug treatment. Needle exchange programs and bleach distribution are viewed, at best, as makeshift responses and, at worst, as the deliberate continuation and support of drug dependence within the African American community.

Reverend Graylan Ellis-Hagler has said, for example (Kirp and Bayer, 1993:39):

First they (the white establishment) push drugs into the community. They cripple the community politically and economically with drugs. They send the males to jail. THEN someone hands out needles to maintain the dependency.

These sentiments have been echoed by several African American leaders, including member of Congress Charles Rangel (D-New York) and activist minister Dr. Calvin O. Butts. It is significant that Ellis-Hagler's position

was influenced by the leadership of recovering addicts in his congregation. Originally, he had been supportive of needle exchange programs. He has indicated that his switch to an opposing stance was in response to his recognition that issues of empowerment and local control were more important than "pushing forth some social policy that came out of some liberal think tank somewhere in America" (Ellis-Hagler, 1993).

The image of African American injection drug users reaching out for drug treatment only to receive clean needles from public health authorities provides additional support for the genocide theory (Thomas and Quinn, 1993). These sentiments have been eloquently expressed by Dalton (1989):

For us (African Americans) drug abuse is a curse far worse than you can imagine. Addicts prey on our neighborhoods, sell drugs to our children, steal our possessions, and rob us of hope. We despise them because they hurt us and because they ARE us. They are a constant reminder of how close we all are to the edge. And "they" are "us" literally as well as figuratively; they are our sons and daughters, our sisters and brothers. Can we possibly cast out the demons without casting out our own kin? (p. 217)

Why can't WE choose which of the many problems facing us to tackle first? Suppose we think that crack is more of a menace than AIDS. Are you willing to help us take on that one? Why do you want US to take all the risks? You say that making drug use safer (by giving away bleach or distributing clean needles) won't make it more attractive to our children or our neighbors' children? But what if you are wrong? What if as a result, we have even more addicts to contend with? Will you be around to help us then, especially if the link between addiction and AIDS has not been severed? … Instead of asking us to accept on faith that we won't be abandoned and possibly worse off once you move on to a new issue, why not demonstrate your commitment by empowering us to carry on the struggle whether you are there or not? (p. 219)

Although individual religious leaders express strongly held views, African American church organizations have to date not taken formal positions either in support of or in opposition to needle exchange programs (Malone, 1994). And several of the more vocal religious and political leaders in such places as New York, Boston, New Haven, and Chicago have been convinced to allow certain needle exchange programs to operate in their cities.

The views of religious leaders in the African American community have been complemented by the views of politicians. For example, in March 1993, Congressman Charles Rangel, in response to a report from the U.S. General Accounting Office (1993), commented (Select Committee on Narcotics Abuse and Control, U.S. House of Representatives News Release, March 26, 1993):

I cannot condone my government telling communities ravaged by the twin epidemics of drugs and AIDS that clean needles are the best we can do for

you. Many of those hardest hit are minority communities like the ones I represent. I believe government has an obligation to do more than just help people use illegal drugs more safely.… To my way of thinking, the continuing debate over needle exchange programs only diverts us from the real issue … that is expanding our capacity to get drug users into effective comprehensive treatment.

When the African American religious and political leaders who have expressed opposition to needle exchange and bleach distribution programs have been convinced that these programs can be valuable in reducing HIV infection and the spread of AIDS and that the commitment to support drug treatment programs will be continued, they have been more willing to give their support. Essentially, their objections are less grounded in moral arguments than in political and practical ones.

The African American church has a long history of addressing the health and human service needs of its members. Awareness of the mounting toll of deaths within a particular community and the need for drastic action to counter the trend, therefore, has sometimes overridden community objections that were at least partly founded in moral and religious views. Some African American church leaders, like Dr. Calvin O. Butts in New York City, have stated that they would not oppose distributing clean needles (Shipp and Navarro, 1991). Butts stated (as cited in Elovich and Sorge, 1991:168):

I'm one who spoke out very harshly against the distribution of condoms and the distribution of needles saying that it's cooperation with evil but sometimes I think that God can mean what people think is evil for good. And if it's going to save lives and it's going to allow for an arresting of this disease in our community … then I think that these measures are not bad measures and a lot of us are going to have to think real hard about how we oppose things that could stop this disease. In drastic times, you have to take drastic actions.

African American mayors of several large cities—such as New York, Baltimore, New Haven, and Washington, D.C.—have supported needle exchange programs. It should be noted that a good number of African American clergy are also politicians. The church plays and will continue to play a pivotal role in policy debates and legislative action concerning these issues. According to Billingsley and Caldwell (1991), 84 percent of African American adults consider themselves to be religious, and almost 70 percent are members of a church. Lincoln and Mamiya (1990) estimated African American church membership at 24 million. Since 65,000 to 75,000 African American churches of various denominations exist in the United States, it is certainly possible that a wider diversity of opinion exists than has been apparent to date. Findings from the Black Election Study demonstrated that

churches were a vehicle for political mobilization and that "exposure to political information in a church setting is highly correlated with church based campaign activism" (Brown, 1991:255).

LATINO/HISPANIC VIEWS

The Latino/Hispanic population in this country is extraordinarily diverse and comprises a number of groups that differ significantly from one another (e.g., Cubans, Mexicans, Puerto Ricans). The panel's limited assessment of potential concerns within the Latino/Hispanic populations did not reveal any organized opposition to needle exchange programs from these communities. On the contrary, some individual community leaders, political figures, and health care providers have been instrumental in their advocacy of needle exchange programs.

First, second, and third generations of Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Mexicans, and new immigrants from Central America constitute a far more complex cultural web than the term Latino community implies. There is no single voice, nor is there a single cultural response. Nonetheless, it is worth noting that almost all of the legal needle exchange programs in New York City are located in Latino/Hispanic neighborhoods, largely due to the advocacy of Yolanda Serrano, a Puerto Rican community worker who served as executive director of the Association for Drug Abuse Prevention and Treatment.

In a recent press release, Latino elected officials, Latino clergy, and the Latino Commission on AIDS called on the Governor of New York and the Mayor of New York City to provide funding for the expansion of needle exchange programs (Latino Commission on AIDS, 1994). Several Latino leaders have confirmed their support for the message of that press release; they include (but are not limited to) members of Congress Jose Serrano and Nydia Velasquez; Assembly members Vito Lopez, Hector Diaz, and Roberto Ramírez; and City Council members Adam Clayton Powell, Guillermo Linares, Lucy Cruz, José Rivera, and Israel Ruiz. Dennis DeLeón, executive director of the Latino Commission on AIDS, stated (Latino Commission on AIDS, 1994:1):

Considering that HIV infection associated with IV drug use is the common route of transmission of the virus among Latinos and Latinas in New York City, it would be criminal to delay expansion of needle exchange programs. Our lives are at stake.

Latino community members have also urged that, if AIDS prevention programs are to be effective, issues of family and children's safety are critical and require that the programs address sexual and perinatal transmission issues as well as transmission through injection drug users (Rodriguez,

1994). Given the importance of the Roman Catholic Church in Latino/Hispanic communities, the recent Latino clergy endorsement for expanding needle exchange programs in New York City may contribute to strengthening community support. However, overgeneralization across Latino/Hispanic communities regarding the above finding should be avoided, because much of the information presented reflects primarily the New York City experience, which was highly influenced by Yolanda Serrano, a respected and charismatic community leader.

LAW ENFORCEMENT VIEWS

As is the case with any controversial issue, there is substantial diversity in opinions within a given community, and law enforcement is no exception. Police departments have often been a major source of opposition to needle exchange programs, and many view needle exchange programs as inconsistent with the war declared on drugs. In some cities, such as San Francisco, where police and elected officials have shown support for the establishment of needle exchange programs and agreed to make the enforcement of drug paraphernalia laws against program clients and staff a low priority (e.g., New Haven and Portland), needle exchange participants have reported being harassed or arrested by police officers (Lurie et al., 1993:151; Stryker, 1989). Enforcement of prescription laws may result in police harassment of drug users in some cities, which in turn contributes to needle sharing among injection drug users (see Chapter 5 for further discussion of legal issues).

The police rank and file understandably have practical concerns about the potential presence of more needles. The fear of sustaining a needlestick injury while searching an injection drug user (or his or her residence) is based on the potential danger for a police officer, and the wearing of rubber gloves provides no protection from this risk.

As part of its effort to gather relevant information, the panel invited representatives of diverse communities with a stake in the outcome to participate in a workshop to discuss their views. Among those who briefed the panel were representatives of the Fraternal Order of Police and the California Bureau of Narcotic Enforcement. Their participation provided insight on the views of two distinct law enforcement entities: the street police officer (local police) and the career drug enforcement or undercover state narcotics officer. The remarks of these individuals reflect mutual agreement on many matters pertaining to needle exchange and bleach distribution programs. The expressed main areas of agreement and concerns can be summarized as follows:

-

In recent years, law enforcement officers have come to adopt a much

-

broader view of drug addiction; they do not view drug abuse as exclusively a criminal justice issue. Addiction is seen as a health care problem with many negative medical and social consequences. The risk of HIV infection is one of many consequences of injection drug use, and needle exchange programs should be viewed as one strategy that may help reduce that risk. However, these programs should not deflect attention from addressing the underlying causes of addiction. As such, treatment and prevention strategies must be the critical components of any drug abuse policy.

-

Within the law enforcement community, the prevailing reaction to needle exchange is negative. The primary reasons for such a reaction are that: (1) police officers understandably have difficulty endorsing something that is illegal, (2) it sends a mixed message and may worsen society's drug problem, and (3) needlesticks to police officers may increase due to an increase in the number of needles in circulation.

-

Given that drug addiction is a health issue, the requirement of a prescription to purchase needles and syringes in pharmacies does provide for at least some degree of control. Medical supervision does provide some assurance that the users are properly instructed about how to use these devices.

The following comment by one of the participants illustrates the complexity of the needle exchange issues as perceived by career law enforcement officers:

When I look at needle exchange, I split it into two sides. One side is a poor public drug abuse policy and the other is a public health care policy that has some merit. So it becomes a war of priorities in terms of which problem is worse, the drug problem or the AIDS problem? I don't feel that needle exchange is good for both of these problems. Being a police officer I cannot support anything illegal, but I also realize that people are dying of AIDS and that is about as serious as you can get. I cannot come out and say that I am absolutely opposed, but I can say I am very concerned about it. Also, there is so much diversity in this country that federally permissive programs will not work unless it is able to be tailored to specific regions.… If someone could convince me that legalizing needle exchange programs will not make the drug problem worse, then I could probably move more toward the support side.

Another important issue raised at the workshop was whether prescription and paraphernalia laws are a practical tool for police officers and prosecutors to use to convict drug offenders. These laws are tangential to the problem at hand, which is to prohibit the sale, possession, and use of controlled substances. However, they do provide police officers and prosecutors with another tool for charging drug dealers and users with a criminal offense when there is no direct evidence of a sale, possession, or use of the

controlled substance itself. Still, as indicated by one workshop participant, most prosecutor's offices would not view these cases as high priority given the limited resources of the criminal justice system.

Reflecting on the dilemmas presented by legislation in the area of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs, another workshop participant commented:

If officials pass legislation to legalize needle exchange programs, police personnel will need to be educated before it will be effective.

HEALTH PROFESSIONAL VIEWS

Two groups of health professionals have direct impact on the behavior of injection drug users and, consequently, on the potential effects of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs: pharmacists and providers of drug abuse treatment services. Their perspectives on these programs differ according to their respective interactions with the injection drug user population. Pharmacists play a critical role in the access of injection drug users to injection equipment, whereas drug treatment service providers can have an impact on the drug addiction and associated drug-use risk behaviors of individuals.

In this section, we briefly summarize the views of both of these health professional groups. As was the case with other community groups whose views were sought, no consensus opinion emerged within or across groups on the potential value of these intervention programs or on the respective role each of these groups should play in the implementation of such programs.

Pharmacists

As we discussed in Chapter 1, several studies have shown a meaningful association between sharing injection equipment and increased rates of HIV transmission (Magura et al., 1989; Calsyn et al., 1991; DePhilippis and Metzger, 1993; Selwyn et al., 1987; Feldman and Biernacki, 1988; Donoghoe et al., 1992; Metzger et al., 1991; Murphy, 1987). Monitoring of pharmacy sales in Connecticut by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has shown that partial revocation of prescription and paraphernalia laws has had a substantial impact on making sterile needles more readily available and has contributed to observable reductions in sharing behavior (Groseclose et al., in press). One important finding of the CDC Connecticut evaluation project highlighted the critical role of pharmacists in facilitating needle availability. The cooperation of these health professionals is crucial

to eliminating important barriers to the availability of needles. However, their disposition to cooperate is at issue.

Various surveys of pharmacists and pharmacy owner-managers have been undertaken to assess their attitudes toward over-the-counter sales and pharmacy-based needle exchange programs. However, as noted by the University of California study (Lurie et al., 1993), a limited number of surveys has been conducted in the United States; to date, only one has been published. The New Orleans survey results reveal that a small portion of pharmacists (14.5 percent) indicated that they sold needles to anyone requesting them. The majority of respondents sold needles only to clients who had a valid medical prescription, even though Louisiana has no prescription law (Lawrence et al., 1991).

Other countries (the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, Australia, and Canada) have conducted surveys of pharmacists and pharmacy owner-managers (see Lurie et al., 1993). The results show similar concerns across countries with regard to selling needles over the counter and participating in a pharmacy-based needle exchange program. The main concerns include potential negative effects on business revenues and the quality of overall services provided to other customers. For example, Glanz et al. (1989) reported that pharmacies believed that the presence of injection drug users would adversely affect business (68 percent) and would lead to an increase in theft (63 percent). Similar concerns were raised in surveys in other countries (e.g., in Australia, Tsai et al., 1988). An additional issue raised by the survey respondents relates to the disposal of needles returned to pharmacies. Survey results also indicate that disposal of used needles represents a disincentive for pharmacies to participate in pharmacy-based needle exchange programs.

These concerns were also voiced by two professional pharmaceutical industry representatives at the panel's workshop on community views. They represented the National Association of Chain Drug Stores (pharmacy retailers) and the American Pharmaceutical Association (professional pharmacists).

The representative of pharmacy retailers indicated that, although the retailers support the establishment of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs, their association does not feel that pharmacies are the most appropriate sites. Areas of concern include:

-

quality of health care services (i.e., providing advice, education, counseling about medications) to customers other than injection drug users may be adversely affected;

-

liability;

-

collection and disposal of dirty needles; and

-

economic implications.

In clarifying that position, it was stated that, if pharmacies were turned into collection sites for dirty needles by encouraging injection drug users to exchange their needles in drugstores, adverse consequences could result because of reduced quality of services provided to other customers. That is, other customers would not receive the needed medical and prescription-related information they have come to expect. Moreover, the retailer representative pointed out that liability concerns arise from having to adhere to rules and regulations set forth by the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), as well as state and local health departments.

For example, OSHA adopted the blood-borne pathogen standard in December 1991. This consists of a comprehensive set of requirements with which an employer must comply to protect employees from exposure to blood-borne pathogens in the workplace. The standards include, among other things, a workplace evaluation for hazard potential, a written plan for treatment and follow-up, and other record-keeping requirements.

If pharmacies were to serve as exchange sites, employees would be placed at potential risk of occupational exposure to blood-borne pathogens. OSHA standards would require that all staff be properly trained on how to handle the contaminated needles. With regard to the economic implications of having pharmacy-based needle exchange programs, it was noted that the costs associated with complying with federal and state regulations would be substantial. This would not include the potential adverse effect of these programs on profit margins caused by increased thefts.

The representative from the American Pharmaceutical Association, whose membership numbers 40,000 professionals, stated that the association has an official policy statement that supports needle exchange programs as part of a comprehensive approach to HIV infection. This approach also includes outreach, counseling, treatment, and community involvement in decisions about how the program should be implemented. Moreover, it is the association's view that pharmacists are in a unique position as health care professionals in communities to play an important role in prevention efforts by expanding sales of needles, by serving as distribution sites for needle exchange (after the appropriate amendments to state and federal laws are made), or both. The association recognizes that not all pharmacists would be willing to participate in such efforts, but it believes that some would, and that a significant impact could be made even if a small proportion of pharmacies participate.

The discussion that followed the workshop presentations by health care professionals raised important issues regarding the professional discretion of individual pharmacists in the 41 states in which there are no prescription laws to determine whether to sell needles to individual customers. In states

in which it is legal to purchase needles, many pharmacists require a customer to either provide a valid medical prescription or to identify oneself (e.g., sign a log book), thereby demonstrating that the intended use is for legitimate medical reasons. In some states, if a pharmacist knowingly sells needles or syringes to a customer for the purpose of injecting illicit drugs, that pharmacist can have his or her license suspended.

Moreover, in states in which there are no legal barriers to purchasing needles, study results have shown that this discretionary decision to sell or not sell has led to differential access across racial groups. For example, Compton and colleagues (1992) reported the results of a study in which two male research assistants (one white, one African American) attempted to purchase needles in 33 pharmacies in St. Louis. Of the surveyed pharmacies:

-

12 percent refused to sell to both purchasers,

-

12 percent refused to sell to the African American only,

-

18 percent informed study purchasers that they did not sell needles/syringes in small quantities, and

-

58 percent sold to both study participants.

The authors reported that the predominant reason given for refusal to sell was store policy.

A final critical point was raised by a workshop participant regarding the willingness of pharmacists to sell needles. We should not expect all pharmacists to be willing to sell needles to injection drug users. However, in communities in which there is a substantial drug abuse and AIDS problem, pharmacists may be more amenable to selling them.

Treatment Service Providers

For most practitioners in the field of substance abuse treatment, needle exchange and bleach distribution programs present a dilemma. Support for such programs is often perceived as a diversion of already unstable funding away from treatment programs. Their efficacy in lowering the risk of HIV infection and contributing to the treatment of addiction has been questioned. Practitioners are concerned that needle exchange and bleach distribution programs run counter to federal regulations. Many also feel that these programs may provide a means to continue behavior that is destructive to the individual, the family, and the community (Primm, 1990).

Drug abuse treatment programs in the United States operate in a constant state of fiscal uncertainty; it is therefore not surprising that support for needle exchange programs is often perceived as diverting scarce financial resources away from treatment. Furthermore, many programs are under

pressure to show evidence of their ability to effectively treat drug abuse. Although drug abuse treatment programs are for the most part funded from sources different from those that fund needle exchange and bleach distribution programs, there is concern that the latter will become attractive alternatives to drug abuse treatment because of their relatively low costs. These views have been publicly expressed by members of the treatment community. For example, Primm1 (1990) states:

There are some theoretical benefits, of course, in providing sterile needles. It's inexpensive, relative to drug treatment. This is why so many people are embracing it and why public health officials are talking of potential control of HIV transmission as being more important than drug treatment. … Needles, syringes, and drugs have been destructive forces.

For some drug treatment professionals and indigenous outreach workers who are attempting to help clients in their struggle to remain drug free, the increased access to needles dispensed by needle exchange programs represents a threat that attention will be diverted from their efforts. The major initial objection of the treatment community to the programs appears to derive from its primary orientation of strict abstinence. Needle exchange programs pose an apparent contradiction to this principal goal of treatment (Wolk et al., 1990). Critics of needle exchange programs indicate that, by implicitly condoning drug use, these programs are sending conflicting messages not only to current injection drug users, but also to those who are at risk of becoming injection drug users (Singer et al., 1991).

At the time of this writing, no empirical study of the views of the drug treatment community on needle exchange and bleach distribution programs has been published. In an attempt to obtain these views, the panel contacted 25 professional and trade associations that represent service providers and asked them to provide any policy or public statements they may have on the issue of concern. Even after mailing a remainder about the original request, the panel received responses from only 13 associations (Table 4.2).

The views of those who responded can be summarized as follows. As shown in the table, of the 13 associations (52 percent) that responded, 61.5 percent support such programs; 38.5 percent have no official or formal position on the issue. A noteworthy observation is that none of the associations that responded indicated that they were against such programs. The official policies of the American Psychiatric Association, the American Public Health Association, the American Society of Addiction Medicine, the National Association of Social Workers, and the National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors are the most detailed (see Appendix B). It should also be noted that both the American Medical Association and the

TABLE 4.2 Views of Professional Associations: Results from a Mail Survey

|

Association |

Responded |

Formal Policy or Public Position |

Position on Needle Exchange Program |

Position on Bleach Distribution |

|

Alcohol and Drug Problems Association of North America |

No |

|

|

|

|

American Academy of Health Care Providers in the Addictive Disorders |

No |

|

|

|

|

The American Academy of Psychiatrists in Alcoholism & Addictions |

Yes |

Under consideration |

Supportsa |

|

|

American Association of Public Health Physicians |

No |

|

|

|

|

American College of Addiction Treatment Administrators |

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

American Medical Association |

Yes |

Yes |

Supportsa |

Supportsa |

|

American Psychiatric Association |

Yes |

Yes |

Supportsa |

|

|

American Public Health Association |

Yes |

Yes |

Supportsa |

Supportsa |

|

American Psychological Association |

No |

|

|

|

|

American Society of Addiction Medicine |

Yes |

Yes |

Supportsa |

Supportsa |

|

Association of Black Psychologists |

No |

|

|

|

|

Association of Medical Education and Research in Substance Abuse |

Yes |

Under consideration |

|

|

|

Black Psychiatrists of America |

No |

|

|

|

|

Chemical Dependency Treatment Programs Association |

Association no longer exists |

|

|

|

|

Drug and Alcohol Nursing Association |

No |

|

|

|

|

National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers |

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

National Association of Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors |

No |

|

|

|

|

National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems |

Yes |

No |

Supportsa |

Supportsa |

|

National Association of Social Workers |

Yes |

Yes |

Supportsa |

Supportsa |

|

National Association of State Alcohol and Drug Abuse Directors |

Yes |

Yes |

Supportsa |

Supportsa |

|

National Association of Substance Abuse Trainers and Educators |

No |

|

|

|

|

National Consortium of Chemical Dependency Nurses, Inc. |

Yes |

No |

|

|

|

National Nurses Society on Addition |

No |

|

|

|

|

Social Work Administrators in Health Care |

No |

|

|

|

|

Therapeutic Communities of America |

No |

|

|

|

|

NOTE: Response rate: 52 percent. a see Appendix A for detailed description. |

||||

American Public Health Association have recently issued a resolution that endorses needle exchange programs.

Treatment issues are complex and have engendered debates among service providers who are dedicated to helping individuals deal with their additions and who have divergent views about the appropriateness and efficacy of various methods that could be used to accomplish their goal. The panel decided that a more detailed discussion of the views presented above was warranted to more fully explore the underlying issues of concern.

Funding

The worrisome issue of competition for funds seems to derive from the fact that services (both addition treatment and needle exchange programs) focus on similar targeted individuals. However, the population being served is the only factor in common between needle exchange and bleach distribution programs and treatment programs. The primary focus of the former is to address the transmission of HIV as an immediate priority, whereas the latter attempt to address drug abuse, which places an individual at risk.

Treatment Efficacy

Researchers have found drug treatment to be effective (Rettig and Yarmolinsky, 1995; McLellan et al., 1992; Gerstein and Harwood, 1990; Hubbard et al., 1989). However, there is a strong tendency to think of total and permanent abstinence from drug use as the only sign of successful treatment, when in fact diminution in drug use may in itself be a valuable outcome. Drug-use disorders are a complex group of chronic conditions that vary not only according to the substance or substances abused, but also according to individual factors such as psychiatric comorbidity, heredity, gender, ethnicity, education, and occupation. Different types of patients require different types of treatment modalities (Normand et al., 1994).

Viewing these disorders as acute problems controllable by will power is a fundamental basis of the misperception that treatment is ineffective. Yet, from a medical perspective, drug abuse and dependence are chronic disorders, much like arthritis or diabetes. They develop gradually and have a course characterized by remissions and relapses, although there is often overall progression over time. Treatments reliably produce relief of symptoms and improvements in function, but not cures.

The introduction of methadone treatment in the mid-1960s represents a substantial shift in ideology by certain members of the treatment community. Abstinence was no longer the sole treatment goal; rather, it reflects an approach to treatment that attempts to minimize the negative behavioral

consequences of addition in lieu of abstinence (Gerstein and Harwood, 1990).

This approach appears to go hand in hand with the objective of most needle exchange programs: promote harm reduction while trying to encourage program participants to enter treatment. This is reflected by the evidence presented in Chapter 3 showing that some needle exchange programs are a primary source of referrals for treatment. Moreover, injection drug users with no prior treatment history have sought out treatment services as a result of their contact with needle exchange programs (Christensson and Ljungberg, 1991; Heimer et al., 1993). It would appear that needle exchange programs are serving as a bridge to treatment for a subpopulation of injection drug users for whom traditional treatment recruiting efforts have been unsuccessful.

Treatment programs for injection drug use are for the most part methadone maintenance programs. Evaluation of these programs has shown repeatedly that increased social functioning, reduced drug use, and reduced criminal involvement do follow from methadone maintenance treatment—for those who remain in treatment (Ball and Ross, 1991; Gerstein and Harwood, 1990; Hubbard et al., 1989; McLellan et al., 1993). For patients who leave methadone treatment prematurely, not many appear to maintain these gains. In a study that is considered to be one of the most careful examinations of this phenomenon, over 80 percent of patients relapsed to injection drug use within the 12 months subsequent to their leaving treatment prematurely (Ball and Ross, 1991).

Given the chronic nature of the disorder, these relapses are also to be expected of some who are in treatment. This point is reinforced by the published findings of an ongoing longitudinal study of HIV infection and risk behaviors among 152 injection drug users in treatment and 103 out of treatment: the elevated risk of out-of-treatment injection drug users was clearly evident (Metzger et al., 1993). Continued illicit drug use was reported by a substantial portion of in-treatment participants.

These data and the results of other studies have documented significant reductions in HIV drug-use risk behaviors among in-treatment injection drug users (Ball et al., 1988; Cooper, 1989; Longshore et al., 1993; Novick et al., 1990). Moreover, the reported data from the longitudinal study by Metzger et al. (1993) show that injection drug users who are not in methadone treatment were significantly more likely to become infected than comparable individuals who were enrolled in a methadone treatment program. That is, 4 percent of those who remained in treatment for the first 18 months became infected, compared with 22 percent of those who stayed out of treatment. Although selection bias cannot be excluded, it would seem that not only is methadone treatment effective in treating the disorder of drug abuse but it also reduces HIV risk behaviors (i.e., needle use) and, more

importantly, HIV transmission. These data also clearly show that in-treatment injection drug users will continue to inject on occasion. Moreover, other studies have found drug treatment experience (i.e., past history of exposure to treatment) to be related to higher levels of HIV risk behaviors for certain injection drug users (Siegal et al., 1995; Ross et al., 1993; Chitwood and Morningstar, 1985).

Federal Regulations

Few treatment programs in the United States have instituted training on how to effectively decontaminate needles or provide information on how to legally obtain sterile needles. Federal regulations governing some forms of drug abuse treatment also are obstacles to drug treatment providers and their patients to make use of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs.

For example, federal regulations concerning take-home medication for patients receiving methadone therapy [21 CFR, part 291.505 (d) (6) (iv) (B) (1)] require clinicians to consider the ''absence of recent abuse of drugs (narcotic and nonnarcotic), including alcohol" in determining whether to grant the privilege of reduced clinic attendance and the provision of doses of methadone (take-home medication) for the days when the patient does not attend the clinic. Consequently, for patients who have relapsed and who may consider using needle exchange and bleach distribution programs to more safely inject drugs, this federal regulation is a disincentive to admit to recent needle exchange and bleach distribution program participation. Such an admission would result in denial or revocation of reduced clinic attendance (or take-home medication) privileges.

In a similar manner, a counselor cannot advise a patient who is receiving or is eligible for take-home medication privileges to continue to abstain from any drug use, while also suggesting participation in needle exchange and bleach distribution programs if drug use does occur. Knowledge of needle exchange and bleach distribution program participation or any other activity that may be indicative of drug use would require—because of federal regulations—drug treatment clinicians to consider denying or revoking the take-home medication status of a patient.

Condoning Drug Use

As we document more fully in Chapter 7, reviews of the empirical data show no evidence to support the charge that needle availability promotes drug use among current or potential users (Schwartz, 1993; Karpen, 1990; Watters et al., 1994; U.S. General Accounting Office, 1993; Lurie and Chen, 1993). Moreover, in considering the current knowledge base on the etiology

of drug use, it is not surprising that a single risk factor—availability of sterile needles—does not play a crucial role in increasing drug use or initiating noninjectors to injection drug use. This critical point was noted by the University of California researchers (Lurie and Chen, 1993) when they stated that "initiation into drug use is influenced by many social, psychological, and biological factors—and not by the simple availability of syringes" (p. 23).

Because treatment is neither quickly nor universally effective at eliminating drug use, some injection drug use may occur even if a major expansion of drug treatment programs were implemented (Joseph, 1989). Also, even if treatment were made readily available, not all injection drug users would be interested in participating. Recognizing this, the approach adopted by needle exchange and bleach distribution programs is a pragmatic one. These programs acknowledge that not all addicts demonstrate readiness for treatment, that many who enter treatment will not be completely abstinent, and that, once abstinent, relapse is endemic to chemical dependence.

SUMMARY

As with other sensitive issues, communities cannot be categorized as simply either supporting or opposing needle exchange programs. The range of views is far more complex. Members of minority communities ravaged by the effects of drug abuse and HIV infection have articulated both opposition and support for these programs. Law enforcement personnel have been divided on the concept of these programs. Health professionals have debated extensively the pros and cons of needle exchange and bleach distribution. Public opinion polls reflect division and a trend toward more favorable disposition to accept such programs as the issues are debated.

Table 4.3 summarizes the concerns of the individual community groups solicited by the panel. They range from fears of worsening drug abuse and crime to concern about promoting immoral activities. The reactions of these stakeholders are not mutually exclusive. All share the concern that handing out sterile injection equipment or bleach bottles to injection drug users does not address the underlying problems associated with drug abuse and in fact may create more negative outcomes. In sum, the main argument against needle exchange and bleach distribution programs is based on perceptions that they do more harm than good.

CONCLUSIONS

That community responses to needle exchange and bleach distribution programs have varied considerably, not only across but also within subgroups

TABLE 4.3 Community Concerns

|

Communities |

Perceptions and Concerns |

|

Common concerns |

• Drug use is illegal and immoral and should not be condoned.; • Providing clean needles to drug users is misguided and dangerous.; • Programs send a mixed message and may worsen society's drug problem. |

|

Ethnic/racial African American |

• Drug abuse epidemic has been consistently neglected and drug treatment programs are either not established or not funded adequately.; • Drug abuse problems and crime in urban communities will be worsened by the implementation of programs.; • Community leaders are not part of decision making in the establishment of programs within their own communities.; • Drugs are deliberately supplied to the black community and these programs promote their continued use.; • HIV is a man-made virus and AIDS may be a form of genocide.; • Public health authorities cannot be trusted because of past negative experiences, e.g., Tuskegee Syphilis Study, and large segments of the black population are regarded as expendable by the white establishment. |

|

Hispanic |

• Complex cultural web in extraordinarily diverse community will require involvement of community leaders for effective implementation of programs.; • Sexual practices and mores, particularly gender issues, must be addressed adequately.; • Issues of family and safety are critical to the establishment of programs. |

|

Law enforcement |

• Drug use is illegal.; • Needlesticks to police officers may increase due to an increase in the number of needles in circulation.; • Programs should not detract attention from addressing underlying causes of addiction.; • Programs must be tailored to needs of specific communities.; • Drug abuse problems and crime in urban communities will be worsened by the implementation of programs.; • Personnel will need to be better educated about such programs and trained to handle situations that may arise before the programs can be successful.; • Question usefulness of prescription and paraphernalia laws. |

|

Communities |

Perceptions and Concerns |

|

Health professionals Pharmacists |

• Quality of health care services provided to noninjection drug user customers may suffer.; • Subsequent negative effects on revenue.; • Liability for occupational exposure of workers and adherence to rules and regulations set forth by DEA, EPA, FDA, and OSHA.; • Disposal of used needles/syringes.; • Lack or ambiguity of prescription laws.; • Personal discretion.; • Involvement in the development of site-specific programs is needed.; • Education and training are needed. |

|

Treatment service providers |

• These programs promote a behavior destructive to the individual, family, and community.; • Funding will be diverted from treatment.; • Public and professional misperceptions about lack of efficacy of treatment.; • Disincentive to participate in programs because of federal regulations dealing with drug treatment and degrees of drug use.; • Largely strict abstinence orientation poses apparent contradiction to programs allowing the continuation of drug use. |

and over time, is the major conclusion of this chapter. Many of their concerns stem from the view that needle exchange and bleach distribution programs are limited to one type of activity: the exchange or distribution of drug paraphernalia to injection drug users. It is therefore possible that programs taking a comprehensive approach could respond to some of this community opposition. Such an approach would include an overall strategy to improve the delivery of health services, including drug treatment services and social services, that address other important needs. It would also include an open public approach that clarifies the concept and explains the multifaceted and multilevel components of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs.

Focusing on the impact of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs on levels of drug abuse has been central to the discussions of these programs. This underlying focus has generated a multitude of hypotheses about their possible harmful effects. It is critically important to articulate these issues, reformulated as hypotheses, in the process of considering the program effects and operationalizing them in such a way as to steer carefully

between the conflicting objectives of the campaigns against the two epidemics of drug abuse and HIV.

For example, when proponents of needle distribution argue that repeal of paraphernalia laws is more important than instituting discrete needle exchange programs because pharmacies are more plentiful, have more convenient hours, and cost less to operate, community concerns need to be acknowledged. Citizen groups and police are concerned about an increase in discarded needles and accidental needlesticks. Pharmacists are concerned about the impact on their other customers if they expand business to serve injection drug users. Public opinion polls are less supportive of needle distribution than they are of needle exchange. This combination of community views suggests that needle exchange, with the systematic collection of contaminated needles, is more palatable than outright needle distribution programs.

Another observation that arises from this chapter is that community support has built gradually for needle exchange and bleach distribution programs. Repeat surveys over time in a single geographic location are consistent in showing an increase in the proportion of respondents who react favorably toward needle exchange and bleach distribution programs. The most recent surveys in Baltimore and the state of Maryland show that a majority favors needle exchange. Similarly, quotes from politicians, drug abuse treatment providers, and African American clergy reflect a change in attitude over time. The change reflects the growing discussion of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs as part of a campaign aimed at stemming the epidemic of parenteral transmission of HIV infection—rather than as an incongruous initiative amidst a broader campaign aimed at drug abuse.

As community concerns are recognized and addressed, the concept of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs is refined. Initial constraints placed by communities on needle exchange programs in New York City and Washington, D.C. (as described in Chapter 3) resulted in programs that were universally recognized as ineffective. With continued dialogue and progressive iterations of balancing community concerns, the concept of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs continues to evolve.

When needle exchange and bleach distribution services are viewed as one of many components of a comprehensive strategy against HIV, a reduction in resistance and broader coalitions for these programs can be expected to follow. At the same time, efforts to develop comprehensive programs must recognize that change or expansion of needle exchange and bleach distribution programs must be combined with significant attention to long-term societal impacts (e.g., on community-level drug use). Failure to include community members in the decision-making process about the implementation

of these programs can fan the flames of fear and distrust within the community (Thomas and Quinn, 1993).

NOTE

|

1. |

Dr. Primm has reversed his original position of opposing needle exchange programs and has stated publicly that he now supports them (Primm, 1995). |

REFERENCES

The Arizona Republic 1993 Poll on AIDS Concerns, January 21.

Ball, J.C., and A. Ross 1991 The Effectiveness of Methadone Maintenance Treatment. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Ball, J.C., W.R. Lange, C.P. Myers, and S.R. Friedman 1988 Reducing the risk of AIDS through methadone maintenance treatment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 29:214-226.

Bannon Research 1990 Massachusetts Telephone Survey, Politics Poll "Media #6" (unpublished material), February 19.

Bates, K. 1990 AIDS: Is it genocide? Essence 21:77-116.

Belgrave, F.Z., and S.M. Randolph, eds. 1993 Psychosocial aspects of AIDS prevention among African Americans. Special issue of The Journal of Black Psychology 19(2) May.

Billingsley, A., and C. Caldwell 1991 The church, the family, and the school in the African American community. Journal of Negro Education 60:427-440.

Brettle, R. 1990 HIV and harm reduction for injection drug users. AIDS 5:125-136.

Brown, R. 1991 Political action. In Life in Black America, J. Jackson, ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Brunswick, A. 1991 Longitudinal Harlem Health Study, NIDA Research Grant R01-DA05142 (unpublished material), April.

Calsyn, D.A., A.J. Saxon, G. Freeman, and S. Whittaker 1991 Needle-use practices among intravenous drug users in an area where needle purchase is legal. AIDS 5:187-193.

Center for Substance Abuse Research 1994 Needle Exchange Programs Supported by a Majority of Marylanders. CESAR FAX 3(28): July 25 (Weekly FAX from the Center for Substance Abuse Research, University of Maryland, College Park).

Chitwood, D.D., and P.C. Morningstar 1985 Factors which differentiate cocaine users in treatment from nontreatment users. The International Journal of the Addictions 20:449-459.

Christensson, B., and B. Ljungberg 1991 Syringe exchange for prevention of HIV infection in Sweden: Practical experiences and community reactions. The International Journal of the Addictions 26(12):1293-1302.

Compton III, W.M., L.B. Cottler, S.H. Decker, D. Mager, and R. Stringfellow 1992 Legal needle buying in St. Louis. American Journal of Public Health 82(4):595-596.