5 Interorganizational Relations

Two medium-size banks in a large U.S. metropolitan area recently came to the same conclusion: each was too small to withstand the market power of its larger competitors. Neither had the resources to compete or to grow and, moreover, both were prime takeover targets for large banks wanting a presence in their metropolitan market. Faced with a future of stagnation at best, and dismemberment at worst, the two banks decided to merge. Today, the combined institution is twice the size of the former banks and is one of the largest savings banks in the United States. The new bank has the size to be a major player in its market and is now pursuing efficiencies of scale and scope never before possible.

This type of interorganizational relationship, and other forms of organizational collaboration and linking together, represent an increasingly common strategy for the survival and growth of corporations as they seek to defend against competitive attack, enter into new markets, and gain access to developing technologies. Interorganizational cooperation, although largely reported as a Wall Street phenomenon, has by no means been confined to the business community, however. New roles for the military in the post-cold war era, such as peacekeeping missions and disaster relief, have increased the importance of multinational operations and posed a significant challenge to the military's cooperation with local relief agencies such as the Red Cross and local government agencies (as the next chapter discusses). Even nations, traditionally concerned with issues of sovereignty, have entered into collaborations with each other in the belief that cooperation in both political and economic ventures is often better than independent action. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the European

Union (EU) represent a new level of international interdependence among neighboring states.

Although corporations, local agencies, military forces, and nations have long attempted to cooperate with or co-opt each other, it is only in the last two decades that relations between organizations have become recognized as a critical tactic for organizational survival, growth, and success in a hostile or challenging environment (Harrigan, 1985, 1986; Gomes-Casseres, 1988; Paré, 1994; Fligstein, 1990; Bleeke and Ernst, 1995).

At least three factors are contributing to this increase in partnerships, networks, consortia, and federations, in addition to mergers and acquisitions. First, businesses compete in a global context today, and the trend is not expected to abate. With this kind of competition—more challenging and rapidly changing—organizational leaders are seeing wisdom in joining forces. Second, there is greater competition for scarce resources today, so more and more are competing for less and less; sharing costs, risks, and scarce resources is making sense to many organizational leaders. Third, there is growing recognition that collaborative behavior, in contrast to competition and individualism, may often (but not always) be a better way to operate.

Today, firms, government agencies, and states are apt to be seen by both researchers and practitioners as involved in a complex web of organizational relations, formal and informal, intended and unintended, that can help or hinder their ambitions. With this awareness has come an explosion of research and conceptualization, if not theory, by social scientists and management scholars that has attempted to understand the forces that prompt organizations to connect with each other and the conditions under which interorganizational relations are likely to succeed or fail. Although at this point there is more theory than evidence, the data suggest that differences of situation, orientation, purpose, culture, and power can affect the outcome of an ostensibly good match.

In this chapter, we characterize the voluminous writings on interorganizational relations of all types. This body of work is large and growing but can be divided into two distinct literatures: (1) macro environmental studies of the political and competitive aspects of relations between and among organizations and (2) micro studies of the processes by which organized groups relate to each other and the factors that are likely to lead to a successful collaboration. We should point out that this chapter is based primarily on literature generated in the United States. There is an equally large and growing body of literature on interorganizational relations that is more international; see, for example, such recent sources as Gerybadze (1994), Kuman and Rosovsky (1992), and Yoshino and Rangan (1995).

The chapter begins with a characterization of the environmental research, including the history of the analysis of interorganizational relations,

the ways in which researchers have conceptualized organizational environments, and the forces that increasingly push organizations to collaborate with each other. It then goes on to discuss the research concerning the processes of interorganizational relations, including the wide range of reasons that organizations collaborate, a taxonomy of types of interorganizational structures that are possible, life-cycle stages in cooperative relations, and a number of other relevant factors, including culture, leadership, evaluation, intergroup relations, and boundary stresses. Finally, we consider the conditions under which various forms of organizational connections are likely to succeed or fail. We end with questions for further research and the committee's conclusions in this area.

Environmental Aspects Of Interorganizational Relations

Early theories of management were intent on perfecting the modern production organization by developing principles of efficient management and applying scientific analysis to organizational problems (Perrow, 1992). Although several schools of thought developed over the first half of the twentieth century, they all had in common a focus on the organization as an independent entity to be managed. Successive theories shifted the focus from the production system to the social system, but for the most part they proceeded from a belief that management science, properly applied, could control the forces necessary to maximize productivity.

This focus on the organization as the unit of analysis, with manipulable variables, began to shift after World War II when systems theory taken from biology, was applied to organizations. Systems theory encouraged researchers to look first at organizations as cybernetic systems capable of self-regulation and eventually as systems that interact with their environment, for example by processing information and other resources from the environment (Boulding, 1956). This ''open systems" perspective on organizations encouraged a new focus for research about organizations and their environments. As Scott put it, "The environment is perceived to be the ultimate source of materials, energy, and information, all of which are vital to the continuation of the system. Indeed the environment is even seen to be the source of order itself" (1987:91). It became clear to researchers and practitioners that much of what an organization needs to succeed is outside the organization itself.

An awareness of the world outside a particular organization has led researchers to realize that much of an organization's environment consists of other organizations. A focus on organizations and their environments stimulated research on how organizations sharing an environment as either competitors or potential allies are affected by their neighbors in organizational

space. Although some of the research is abstract, much of it has prescriptive implications for organizations attempting to manage their relations with other organizations in order to ensure survival, gain market power, and otherwise improve their performance.

Conceptualizing Organizational Environments

Organization Sets, Fields, and Networks

In the 1960s and 1970s, organizational scholars began conceptualizing relations between organizations in order to study them. Several levels of analysis have become standard ways of discussing interorganizational relations. The first, the organizational set, is an application of a social psychological model, the role set, to an organization. Just as an individual has a set of different roles he or she plays with other people—spouse, parent, worker, friend—an organization is conceived as having a set of relations with other organizations (Blau and Scott, 1962).

Organizational set analysis concentrates on the relationships of a single organization to see how those relationships affect its activities and performance. In many situations, however, organizational outcomes are the consequences of groups of organizations acting in ways that affect each other. Variously called, with somewhat different meanings, the action set (Aldrich and Whetten, 1981), the interorganizational field (Warren, 1967), and the industry system (Hirsch, 1975), this unit of analysis looks at relationships among groups of organizations that interact over time in ways that affect each other.

Hirsch's comparative analysis of the recording and pharmaceutical industries demonstrates the impact of the structure of an interorganizational field on the overall performance of an industry (1972; see also 1975). Although both pharmaceutical and recording companies have important similarities, for example, gatekeepers (physicians and disc jockeys) who mediate between themselves and their customers, the drug industry has been far more successful than recording companies in protecting their interests in patent protection, distribution, and pricing. Hirsch's study points to the superior collective efforts of drug companies in pursuing common interests, compared with the disorganized and misdirected efforts of recording companies that attempted to bribe disc jockeys in what became known as the payola scandals. He attributed at least some of the drug industry's higher profitability to the character of the relationships among organizations in the industry. Similarly, Miles and Cameron's study of the cooperative strategies employed among the Big Six firms within the tobacco industry (1982) demonstrates the effects on profitability of organized efforts among ostensible competitors.

Although organizational sets and interorganizational fields are still important conceptual categories, much recent research utilizes the concept of an organizational network. Network analysis differs from organizational set and industry analysis in seeking not only to identify the relationships among organizations but also to examine the character and structure of those relationships, usually by modeling them mathematically (Nohria and Eccles, 1992). The premise is that the networks within which an organization is embedded both constrain and provide opportunities for action. Organizational actions, and hence performance possibilities, are to a large degree explained by an organization's position within a network of organizations.

One body of research looks primarily at nonprofit community service organizations (Laumann and Papi, 1976; Galaskiewicz, 1979; Knoke and Rogers, 1979) and has the advantage of looking closely at the multiple and overlapping ties between organizations in a community, usually a geographically bounded setting. These studies tend to show how interdependencies among organizations that exchange money, people, political support, and other resources come to shape possibilities for action. Focusing on a geographic region, however, limits researchers' ability to assess the impact on performance of forces and organizations outside the region.

Much of the recent interest in strategic alliances, joint ventures, and other forms of interorganizational relationships came about as an attempt to facilitate or manage network relations, increasingly possible since the Reagan administration's weaker enforcement of antitrust laws and the passage of legislation permitting some forms of research consortia. Another important factor shaping network research is the observation that new high-technology industries, notably biotechnology and electronics, are characterized by intense patterns of formal and informal network relations. Barley and colleagues (1992:317) note that, in these industries, scientific advances come so quickly that "even well-heeled corporations cannot hope to track, much less fully exploit, relevant scientific advances by relying solely on the published literature and their own research operations. Instead, relevant technical knowledge is more efficiently obtained by direct access to research conducted elsewhere" and made available through interorganizational relations.

The authors note, too, that whereas some high-technology industries such as electronics build on scientific communities such as chemistry and physics that have been integrated into industrial manufacturing since the nineteenth century, biotechnology is founded on a wholly new community of participants. Recent advances in recombinant DNA and hybridoma cell formation suddenly brought cutting-edge molecular biology into the center of the pharmaceutical and agricultural industries. In biotechnology, far more than electronics, however, strategic alliances between small research firms and well-funded larger corporations are common because of the expense

of clinical trials necessary for government approval of biotechnology products. They conclude that "the way in which a firm participates in the network is integral to its strategy for survival and growth" (p. 343).

Another and perhaps most important factor in prompting research on organizational networks is the observation that business networks have been widely successful in the global economy. Whereas the U.S. economy is based on a belief that competitive individualism is the appropriate principle for exchange relations among economic actors—a principle that is institutionalized in laws and practices such as arms-length bidding relations between suppliers and buyers, antitrust regulation, and insider-trading laws (Williamson, 1992; Biggart and Hamilton, 1992)—this principle does not exist in many other successful economies.

Regime Analysis

Another approach to analyzing interorganizational cooperation, international regimes, was developed from the need to understand cooperation in the less structured global system. An international regime is a set of explicit or implicit principles, norms, rules, and decision-making procedures around which actor expectations converge and that help coordinate actor behavior (Krasner, 1982; see also Mayer et al., 1993). Some examples include the regimes surrounding nuclear nonproliferation, the law of the sea, and the nascent international environmental regime (Young, 1989). Regime analysis represents a movement away from purely institutional analysis (Kratochwil and Ruggie, 1989) to one that looks at broader and sometimes less formal patterns of cooperation (Kahn and Zald, 1990).

Organizations play several roles in the regime. Certainly, cooperation among organizations can be the driving force behind the development of an international regime or define its structure; an example is the coordination among national health agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and the World Health Organization. Yet organizations, and cooperation among them, can also be the consequence of or institutionalized manifestation of coordination between different groups or states in the world. International cooperation can also occur outside or independent of organizations, providing the analyst with a broader conception of behavior than is present by a pure concentration on institutional behavior. A focus on organizations and cooperation is also enhanced by understanding the broader milieu in which organizations operate and cooperation emerges (Haas, 1980). The limitations of the regime framework, however, include its difficulty with accommodating change, its being too issue-specific to permit generalizations, and its limited applicability to more structured, less anarchic environments than global politics (for a more detailed critique of this approach, see Strange, 1989).

Collaboration as an Organizing Principle

Although competition, not collaboration, has historically been the organizing principle for organizations and markets, particularly in the United States, there is growing evidence of collaboration and other forms of managed interdependence among firms and not-for-profit organizations in the United States. Firms in a market are more likely to compete, and not collaborate, when the market is stagnant or declining and resources are increasingly scarce (Porter, 1980). Competition is also more likely in situations in which institutional factors—such as a legal system that supports antitrust regulation—or deeply rooted distrust among members of an industry, militates against collaboration.

A number of forces, many of which are on the increase around the world, prompt organizations to collaborate with each other. Resource dependency theory (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978) argues that, because a focal organization must depend on other organizations for the inputs it needs to survive, it may be in its interest to attempt to manage the organizations on which it is dependent. They argue that mergers and acquisitions, which represent total control of another organization, are only the most extreme of an array of strategies that organizations can employ to coordinate with or impose their interests on other organizations. They may use a series of "bridging strategies" (Scott, 1987:209) to lock in the supplies or support of another firm, including contracting, strategic alliances, and co-optation, the incorporation of important external agents into the firm, for example by forming interlocking boards of directors (Palmer, 1983; Mizruchi and Schwartz, 1986).

Transaction cost economics (Williamson, 1992) argues that, under conditions of high uncertainty and small numbers of alternative suppliers, collaboration can improve cost-effectiveness and therefore improve the profitability and competitive performance of an organization. Other economists argue that collaboration weakens an organizational field by reducing competition (Scherer, 1980; Caves, 1982), thus leading to higher prices and less innovation. Ouchi and Bolton (1988), however, found in a study of micro-electronics and other industries that participation in collaborative research and development (R&D) ventures strengthened the firms' global competitiveness.

Although much of the recent impulse for mergers and acquisitions was fueled by the development of the junk bond market in the 1980s and the use of purely financial criteria to mate corporate partners, a decade of failed alliances has made organizational executives less sanguine about entering into this type of long-term, permanent acquisition. In fact, research suggests that as many as half of all domestic mergers and acquisitions are financial failures (Paré, 1994). It is now clear that successful collaborations

among organizations, even those with ostensibly good financial or strategic reasons to collaborate, are difficult to achieve. Financial synergy may be a necessary component of a successful relationship for a market-based firm, but compatible leadership style, strategic orientation, and culture are necessary as well, as discussed below (Sankar et al., 1995; Fedor and Werther, 1995). This is no less true of not-for-profit organizations, especially those with a strong missionary culture such as religious organizations and the military, in which value clashes can doom an alliance (Wallis, 1994).

Frameworks For Understanding Interorganizational Processes

Reasons for Collaborating

Both research and practice show that organizations enter into relations with each other for a wide range of reasons: (1) long-range survival (Burke and Jackson, 1991); (2) gain in market power (Porter, 1990); (3) synergy (Kanter, 1989); (4) risk sharing (Bleeke and Ernst, 1993; Harrigan, 1986); (5) cost sharing; (6) subcontracting and outsourcing (Porter, 1990); (7) technology sharing (Harrigan, 1986); and (8) knowledge of a market.

As steps toward linking up with another organization begin, the parties involved are faced with at least two clear yet perplexing paradoxes, ones of vulnerability and control (Haspeslgh and Jemison, 1991). Organizations have to decide how much they will cede control to their partner.

The paradox of vulnerability—trust versus self-preservation—is concerned with whether or not the recent proliferation of interorganizational collaborations represents a new spirit of cooperation or a new level of cost-cutting and market exploitation. From one perspective, collaboration is valuable in and of itself, opening gateways to such activities as organizational learning and transformation. To facilitate this transformation, however, partners must openly share information about strategic objectives, organizational resources, and internal challenges, which paradoxically increases vulnerability to acquisition, loss of market share, proprietary control of valued resources, and other sources of strategic advantage. Thus, collaboration can be seen as both promoting and threatening an organization's long-term stability and viability. Nevertheless, an avoidance of collaborations may also represent a costly choice, with inefficiencies and insufficient learning possibilities. The challenge is to find the right partner (one with complementary resources, compatible business and cultural characteristics, and similar philosophies regarding business goals and the collaboration's role in achieving them) yet not to be so protective of organizational resources that the collaboration becomes impossible.

The paradox of control—stability versus synergy—concerns the tension

faced by managers of interorganizational relations between the impulse to control the outcome of the collaboration and the potential synergy that can result from the absence of tight controls and management. Although a clear division of authority and decision making in interorganizational relations may reduce potential conflicts arising from partners' differing strategies, cultures, and work systems, a clear division may also reduce the likelihood that genuinely new perspectives and possibilities will emerge from the relationship. An organization therefore risks undermining the synergistic objectives that led it to enter a collaboration in the first place when it institutes tight controls that may be intended to guarantee success. This is especially true when a collaborating organization uses less measurable objectives for indicating success, such as organizational learning and management and work styles.

A Partial Taxonomy Of Interorganizational Governance Structures

As a guide to understanding interorganizational relations, we present a taxonomy of interorganizational governance structures, based on work by Kahn (1990) and Harrigan (1986). Although not all-encompassing, it is comprehensive enough to provide a road map for how to understand interorganizational relations. The following taxonomy moves from relatively less interdependent relations to relations in which interdependence and its management are key.

- Mutual Service Consortia; Research and Development (R&D) Partnerships . Organizations pool their resources to procure access to information, technology, or some other service too costly to acquire alone (Kanter, 1994). Tasks (including financial support) are distributed among the participants, and the proceeds are returned to participants according to the terms of the agreement. No separate entity is created for the management of this relationship.

- Cross-Licensing and Distribution Arrangements. Organizations enter into agreements formalizing the limited sharing of technology or other product attributes such as brand names or markets. These arrangements are strictly contracted and bounded in scope and duration.

- Joint Ventures. Two or more organizations ("owners") combine varying resources to form a new, distinct organization (the "venture") in order to pursue complementary strategic objectives. This new organization is jointly owned and managed, and proceeds are distributed between the venture and owners according to a formula agreed on by the owners.

- Strategic Alliances. Similar to ventures, two or more organizations

- combine resources in pursuit of mutual gain. However, in a strategic alliance, a new firm is not created. Although interdependence is, of course, required for a joint venture to work effectively, the characteristic of interdependence is essentially the same as that required for any organization, whereas for a strategic alliance to work effectively, two distinct organizations must learn to cooperate and depend on each other.

- Value Network Partnerships. Organizations join forces to capitalize on potential efficiencies in the production and/or distribution process (Porter, 1990). Whereas each participating organization is responsible for one area of the production system, the participating organizations are highly dependent on one another for the ultimate delivery of their product. This form of collaboration concerns the alliance of certain organizational functions such as production, and typically not multiple functions that encompass more of a particular business or business units as in a strategic alliance.

- Internal Ventures. An organization acts independently to create a distinct entity, from within its own ranks, for the purposes of expansion, innovation, or diversification. These are often established with the goal of capitalizing quickly on entrepreneurial initiatives coming from members of the organization's work force. When action is then taken to establish a joint venture with another organization, the description above of a joint venture would then apply.

- Mergers/Acquisitions. A special case of interorganizational relations; when they are established, problems of interdependence between organizations become issues of within-group functioning and are directly related to organizational performance. Acquisitions are preferred to ventures and alliances when shared ownership of initiatives is not desired.

Table 5-1 presents the types of interorganizational relations, along with some of the situational determinants of their formation and their likely outcomes (Harrigan, 1986; Porter and Fuller, 1986).

Situational Determinants

In the design of an interorganizational relation's governance structure, three questions are key: (1) What are the reasons for collaborating? (2) How will both risks and benefits be distributed? (3) What will be the indicators for successful achievement of participants' mutual goals? The responses to these three questions suggest the degree of managed interdependence appropriate to the relationship between partners and, indirectly, the ideal governance structure for the relationship.

TABLE 5-1 Taxonomy of Cooperative Interorganizational Relationships

| Degree of Managed Interdependence |

Interorganizational Relationship |

Strategic Purpose |

Ownership/Division of Proceeds |

| Least managed |

Market (competitive) |

|

|

|

|

Mutual Service Consortium, Research & Development Partnerships |

Contracted pooling of resources for shared access to valued commodity: market, technology, process |

No shared ownership/negotiated division of proceeds |

|

|

Cross-Licensing and Distribution Arrangements |

Limited sharing of technology and markets |

No shared ownership/negotiated distribution of proceeds |

|

|

Strategic Alliance |

Reciprocal exploitation of resources for less specified mutual gain |

Varying shared ownership and managerial control/negotiated distribution of proceeds between owners |

|

|

Joint Venture |

Reciprocal exploitation of resources for specific mutual gain in presence of compatible strategic objectives |

Varying shared ownership and managerial control/negotiated distribution of proceeds between venture and owners |

|

|

|

|

|

TABLE 5-1 Taxonomy of Cooperative Interorganizational Relationships (cont'd)

|

Issues/Obstacles |

Boundary Characteristics |

Key Psychological Phenomena Affecting Viability |

Milestones for Success |

|

(Limited or unmanaged interfirm cooperation in marketplace) |

|||

|

Possible development of competitive conflict (shared product/market) |

Stable, contained interface, high constituent power, committee, slow-moving |

Perceptions of equity, competitor benefits |

Negotiated distribution of consortium outputs, quantifiable, static |

|

Loss of control of knowledge re technology and markets |

Stable, contained interface, high constituent power, committee, slow-moving |

Perceptions of equity, competitor benefit |

Performance of both organizations |

|

Firms risk ownership and organizational identity, because relationship leveraged by equality/inequality of shared investment/commitment and distribution/evolution of bargaining power |

Boundary-spanning project team(s), multiple interfaces, varying constituent power, high-stress on boundary-role persons |

Perceptions of equity (need measurement systems), perceptions of power, compatibility of cultures, intergroup trust and competition, resistance to cooperation at operational level |

Venture performance, value added to owners is negotiated, benchmarked, monitored, revised (monitoring and control systems needed) |

|

Conflict between owners, between owners and venture likely to develop as each organization's performance, priorities, and environment change; Firms risk valued assets, because relationship leveraged by equality/inequality of shared investment/commitment and distribution/evolution of relative bargaining power |

Hybrid organization/culture buffers cooperating partners, venture identity distinct from parent organizations, varying constituent power as a function of dependence and bargaining agreement constraints |

Perceptions of equity (need measurement systems). perceptions of power, compatibility of cultures (including management style, work norms, and values), owner-venture competition, resistance to cooperation at an operational level |

Venture performance, value added to owners is negotiated, benchmarked, monitored, revised (monitoring and control systems needed in owner organizations and in venture) |

|

Dilemmas of control and synergy |

|||

| Degree of Managed Interdependence |

Interorganizational Relationship |

Strategic Purpose |

Ownership/Division of Proceeds |

|

|

Value Network Partnership |

Reduce environmental variability, streamline production and delivery systems (raise competitor entry costs) |

No shared ownership/contracted provision of products, services |

|

|

Internal Venture |

Capitalize on internal entrepreneurial initiatives, exploit opportunities requiring faster response without sharing resources |

Negotiated internally |

| Most managed |

Merger/acquisition |

Merger with/acquisition of competitor or affinity organization in support of strategic objectives |

No shared ownership/division of proceeds |

Strategic Purpose

Some collaborative initiatives are extremely limited in objective and scope. They involve a relatively passive pooling of resources for the participants' mutual benefit. For instance, participants might share information regarding a particular technology or economic developments in a specific market or region. In the private sector, relationships of this kind usually take the form of mutual service consortia or R&D partnerships.

| Issues/Obstacles |

Boundary Characteristics |

Key Psychological Phenomena Affecting Viability |

Milestones for Success |

||||

| Possible lock-in with standardization/competitive pressures for innovation; Conflict re cost-effectiveness of provided product services, allocation of profit |

Multiple interfaces: sharing of systems, information, processes, and resources Varying constituent power, high stress on boundary role persons |

Perceptions of equity (need measurement systems) Perceptions of power; Compatibility of cultures Intergroup trust and competition, resistance to cooperation at operational level |

Market share, profit margins, other markers of organizational performance and efficiency; Partner relations persons and perceptions |

||||

| Dilemmas of control and maximized return; Conflicts re management control, resource provision and output distribution |

Multiple interfaces: sharing of systems, information processes, and resources Varying constituent power, high stress on boundary role |

Intergroup competition and envy, resistance to cooperation at operational level |

Venture performance; Value added to owners is negotiated, benchmarked, monitored, revised (monitoring and control systems needed) |

||||

| Interorganizational dynamics become intraorganizational challenges |

Boundary expansion/subsumption |

Perceptions of power, perceptions of implications for performance and related impacts on cooperation, compatibility of cultures |

Organization performance |

||||

| Note: Adapted from R.L. Kahn (1990) for concept of managed interdependence dimension and Harrigan (1986) for strategic functions of most relationship types. |

|||||||

Relationships involve relatively little risk on the part of the participants. They are bounded in scope and often in time as well. Mutual service consortia and R&D partnerships can provide extremely valuable resources to their participants but demand very limited cooperation.

Similarly, when an organization shares a specific asset with another organization, as in cross-licensing or distribution arrangements, the interface

between participating organizations is relatively specific and contained. Cross-licensing and distribution arrangements usually involve the licensed use of another organization's technology, production or distribution methods, or brand name, with the purpose of bolstering organizational performance.

A more complex and interdependent relationship is necessary when a collaboration involves reciprocal exploitation of resources in pursuit of mutual gains. There are two related models for such a relationship: the joint venture and the strategic alliance. Joint ventures involve the creation of a distinct organizational entity for managing the overlapping goals of the sponsoring organizations. Strategic alliances attempt to avoid potential conflicts by limiting the power of the (new) organization responsible for the founders' mutual gain, but relations of this type often have the effect of exacerbating tensions between the founders (Harrigan, 1986).

Attempts to capitalize on linkages in the value network by strengthening relationships among suppliers, producers, distributors, etc., take the form of value network partnerships. Relationships of this type are undertaken to increase organizational efficiencies. For business organizations, they have the added indirect benefit of increasing industry competitiveness by raising the costs of competitor entry (Porter, 1990).

When an organization wishes to capitalize on internal initiatives or to sponsor pursuit of a goal that is not supported by existing systems, internal ventures can serve as valuable models. In an internal venture, a new endeavor can be sponsored without the sharing of resources with outside organizations. The paradox of control is especially important to internal ventures, as organizations struggle to sponsor initiatives that are by definition beyond their typical realm of expertise.

Moves to gain control over competitors or affiliates by expanding organizational boundaries clearly fall under the acquisition model. Similarly, the conditions under which mergers are to be emulated is straightforward—mergers involve the creation of a new organizational entity through the dissolution and recombination of previously existing boundaries.

Ownership of Responsibility

The more a relationship is managed, the more ownership of responsibility and the division of proceeds are shared. The exception to this statement is the case of a merger or acquisition in which the former separate ownership becomes one. In the middle of the continuum are joint ventures and strategic alliances. According to Yoshino and Rangan (1995), there are basically three types of ownership structures in strategic alliances: (1) nonequity, in which neither partner owns a part, (2) equity stake in the other partner, and (3) a separate alliance company, a joint venture that both partners fund (usually 50/50). They suggest that the best ownership structure for an

alliance is one that fits the overall strategy of the collaboration—if goals are limited, then the ties can be comparatively loose. If the alliance is critical to long-term success, then a tighter structure is warranted. The point is that the degree of ownership and the division of proceeds should be linked directly to the mission and strategy of the respective partners.

Obstacles to Cooperation

Issues and obstacles to cooperation between and among interorganizational relationships can be far-ranging. This is true both in practice as well as in the literature. Oliver (1990) has identified five critical contingencies that affect different types of relationships, such as trade associations, joint ventures, and corporate-financial interlocks. The five are asymmetry, reciprocity, efficiency, stability, and legitimacy. We can use her schema to consider briefly issues and obstacles to cooperation:

- Asymmetry. A potential obstacle is an imbalance of power and control between or among the partnering organizations. This is the case when one of the partners wants to dominate the other so that desired resources can be controlled by the dominant partner.

- Reciprocity. More or less the opposite of asymmetry, the assumption being that cooperation and collaboration are emphasized as opposed to domination; obstacles will arise if there is perceived inequity in, for example, sharing of resources; trust is key to this relationship aspect. Reciprocity more often occurs when the partners are pursuing a new venture rather than merely sharing resources (see, for example, Pfeffer and Nowak, 1976).

- Efficiency. Often relationships are formed to improve internal efficiencies for one or both of the organizations; a strategic alliance between two hospitals, for example, might result in the purchase of one high-technology diagnostic tool instead of two and thereby reduced costs. Again, both hospitals must experience better efficiencies for this dimension of the relationship to be perceived as equitable; otherwise, there is a major obstacle.

- Stability. When one of the partners, for example, copes with its external environmental uncertainties far better than the other, then there is the potential for imbalance in the relationship. If one of these partners spends more time, energy, and money on market research in order to reduce uncertainty in the external environment, then the possibility of an obstacle to the relationship arises.

- Legitimacy. The partners are attempting to enhance their reputations, images, and prestige in their environments by joining together; with the passage of time, one of the partners may benefit more than the other, which sets up an obstacle to further cooperation.

These categories of Oliver's are informed by and summarize many studies and so contribute to a better understanding of interorganizational relationships. In practice, there are other ways of categorizing potential obstacles to effective relationships, e.g., cross-cultural barriers. Furthermore, over time in a relationship things change, often as a consequence of the rapidly changing environment.

Likely Outcomes

The choice of organizational governance structure—joint venture, consortia, merger, etc.—has profound effects on many aspects of the collaborating organizations. We explore briefly the consequences of these choices according to (1) boundary characteristics, (2) psychological dynamics, and (3) milestones for success.

Boundary Characteristics

As the structure chosen for an interorganizational relationship shifts from least managed to most managed, boundaries of interdependence between and among the partners become less distinct. Boundary roles can be seen in terms of two forms of negotiation: the bargainer and the representative (Druckman, 1977; Walton and McKersie, 1965). At the least managed end of the continuum, the individuals who are relating across organizational boundaries have two duties—to represent and to bargain. Moving toward more managed interdependence, bargaining becomes even more salient. At the merger stage, the bargainers do their jobs and then ''blend or integrate themselves out of role existence."

Psychological Dynamics

Findings from cognitive psychology contribute to our understanding of interorganizational relationships. For example, Schwenk (1994) points out that the biases of decision makers can heavily influence the degree of success in interorganizational relations, for example, through overconfidence (see also Nisbett and Ross, 1980).

Perceived equity may be an issue. In a recent merger of two financial firms, the early slogan was that it was a "merger of equals." Members of each firm would be treated fairly and end up in the merged organization with parity. A few months following the merger, it was clear that the assumption of equity was violated. Of the top 19 executive positions, 16 were filled by members of one of the previous firms, and only 3 came from the other organization. This outcome, as might be expected, caused a significant setback in the progress of the merger. Had the original position

been one of acquisition instead of merger, different expectations and perceptions regarding equity would have been established. Being acquired does not, as a rule, create expectations of parity. In a joint venture, issues of equity are typically specified clearly. As we move toward the least managed end of the continuum, matters of equity are easier to manage because the partners do not interact with one another as intensively.

Milestones for Success

For commercial enterprises, the milestones are expressed in financial terms, such as increased market share, new products developed as a result of the collaboration, an expansion of the distribution systems, etc. For consortia or R&D partnerships, milestones are much more varied. Increasing the talent pool, accumulating more knowledge faster, having access to information formerly unavailable, and saving on costs of conducting certain lines of research are but a few of the possible indicators for success in collaborations outside the commercial sector.

Life-Cycle Stages In Collaborations

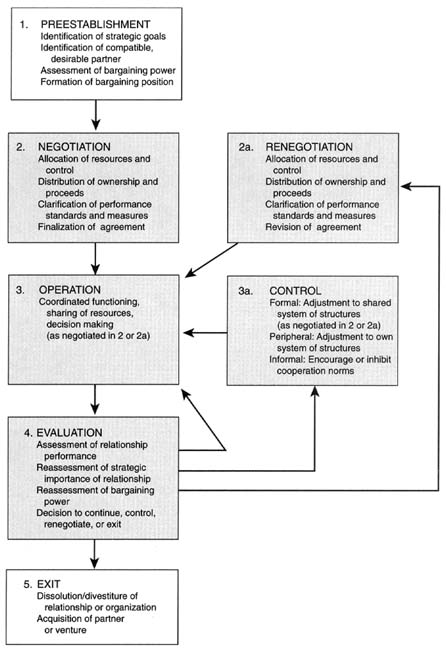

Regardless of the eventual structure of a particular cooperative agreement between organizations, clear patterns characterize the process by which two organizations negotiate an interorganizational arrangement. The movement through these processes can be thought of in terms of a life cycle of interorganizational relations. Figure 5-1 presents a schema for such a life cycle, based on observation of a number of organizations; the shaded boxes indicate processes that occur continuously during the life of an agreement between organizations.

Preengagement Stage

The preengagement stage refers to the state of the organizations prior to the initiation of a particular collaborative endeavor. In business relations, this stage usually involves the voluntary selection of another organization with which to collaborate. In the public sector, it is far more likely that collaboration is mandated, as in the case of peacekeeping efforts between allies or the coordination of disaster relief efforts by state and local agencies. Private-sector firms sometimes find themselves forced to collaborate, however; for example, corporate headquarters in pursuit of a particular goal might mandate that a subsidiary collaborate with another subsidiary or with an outside organization.

When collaboration is a voluntary option, an organization's leaders have the luxury of assessing collaboration as a means for achieving long-term

goals. An organization may also be on the receiving end of an offer to collaborate, prompting reassessment of their organizational strategy in order to respond to a proposal. The approached organization also enters the preengagement stage.

Potential or mandated partners should then be evaluated for compatibility. The first approach to evaluation assesses similarities of management and business philosophies, abilities to communicate, and interpersonal trust; the second approach is an assessment of the organizations' relative bargaining power in the relationship. Intangible factors, including each partner's perceptions of the other's reliability, trustworthiness, and culture, will exert an influence on initial bargaining positions. When the choice to ally with another organization is voluntary, intangible factors weigh more importantly in deciding whether or not to proceed with a relationship. Even when the relationship is not mandated, however, evaluation during the preengagement stage can identify areas of concern that might be addressed in the formal governance agreement created by the partners.

These assessments will affect each organization's perception of the distribution of power, dependence, and control in the relationship and thus the choice of bargaining position as the agreement concerning governance of the relationship is negotiated. Because in this initial stage partners may not be entirely forthcoming with one another about their formulas for determining the strategic value of the relationship, many partners may not even come to realize that their respective assessments of the relationship's value and potential arise from widely differing evaluation systems. As a result, partners who may be quite compatible may never proceed to negotiation or may fail to capitalize on these potentials as they enter their relationship. Similarly, partners who initially appear compatible may proceed to negotiate a relationship that, upon closer examination, would be deemed inappropriate.

Negotiation Stage

If partners advance to the point at which they discuss formally the allocation of responsibilities, resources, and authority that would exist in the relationship, they have begun, at least informally, to manage their interdependence. In the negotiation stage, the provision of inputs to and the division of proceeds from the relationship being created is negotiated. If either inputs or proceeds are relatively intangible (for instance, if one organization is offering to teach a participative management style as one of many inputs, and the counterpart organization offers insight into marketing to a new segment), then specific measures by which to assess the relationship's performance have to be created. These measures will need to be true to the interests of the participating parties, but also relevant to the performance of

the collaboration and not so difficult to measure that they overburden the new system with excessively bureaucratic monitoring and measurement systems. The negotiation stage thus demands the management of the paradox of control; systems that support the achievement of collaborative objectives must be created, yet these systems must be flexible enough to allow both expected and unforeseen benefits of the collaboration to emerge.

Negotiators on behalf of the partnering organizations are in the difficult position of protecting the interests of their host organizations as well as the viability of the partnership (Adams, 1976). Cultural differences, and other differences in perspective, will have a considerable impact on the effectiveness of negotiations in satisfying these dual objectives (Bontempo, 1991). Differences in cultural expectations regarding negotiation behavior, measurement, record keeping, and control systems and in approaches to strategic planning can all be expected to clash at the negotiation table. Furthermore, characteristics of negotiators' host organizations will have an influence on the course of negotiations; cultural characteristics such as need for control, trust of outsiders, and perceptions of relative power will influence both the expectations placed on negotiators and the range of negotiating behaviors available to them (Druckman and Hopmann, 1989).

Operation Stage

After the agreement has been finalized, the collaboration proceeds to the third stage, operation, in which the agreement is implemented. The relationship now consists of an exchange of resources across organizational boundaries; if the relationship is a joint venture, the owners work with the venture as an independent system rather than a theoretical entity. Even if a new formal organization has not been created, the reality of working across organizational boundaries at many functional levels is likely to be quite different from the experience of courtship and negotiation. In order to facilitate cooperation at managerial and operational levels of the organization, employees need to be informed of the strategic value of the collaboration (Kanter, 1994), criteria for evaluating the relationship's success, and the relationship of their jobs to these criteria. New behavior by managers and other employees also needs to be structurally supported and systemically rewarded. Managers and operational employees are in a situation similar to that in which negotiators found themselves, with their loyalties at least partially divided between fulfillment of their responsibilities to their home organization and support of the collaboration. This tension can result in a serious threat to the collaboration's viability, especially if employees are receiving mixed signals about their roles in the collaboration or about senior management's commitment to its success.

Several other cultural and psychological phenomena can be expected to

influence cooperation between collaborating organizations. Compatibility of work norms has a powerful effect on cooperation between the groups. The degree to which work-related behaviors such as timing, quality, and sharing of information and other resources are met influences employees' willingness to cooperate in the future.

The perceptions that members of the participating groups have of each other also affect their likelihood of cooperation. When group relations are characterized by a climate of trust, group members are more likely to help one another; if there are perceptions of competitiveness or ill will, discrimination against outgroup members is far more likely (Flippen et al., 1995). Smith and Berg (1987) indicate that a focus on the mutual stake that interdependent groups share helps to reduce intergroup resentments.

Evidence of the importance of perceived future achievement in mitigating resistance to intergroup cooperation (Haunschild et al., 1994), supported by social identity theory (Tajfel, 1981, 1982), suggests that members' perceptions of interorganizational endeavors coincide with their own goals. This can be achieved through the use of communication systems that reinforce the strategic importance of the interorganizational effort. Social identity theory research also points to factors that increase people's positive feelings about dissimilar groups. The works of Singer et al. (1963), Fishbein (1963), Druckman (1968), and Brewer (1968) can be taken together to indicate that more favorable attitudes are expressed toward dissimilar others from groups that are perceived to be (1) allies, (2) similar to one's own group, (3) comparably skilled or advanced, and (4) interested in membership in one's own group (Druckman, 1994). Intraorganizational communications can support the likelihood of intergroup cooperation by highlighting or encouraging any of these factors.

Evaluation

Regardless of specific criteria, though, evaluation of a multiorganizational relationship's performance occurs continuously on an informal basis, and it should be undertaken formally by all participant organizations on a periodic schedule. However measured, mutually satisfactory performance lays the groundwork for ongoing cooperation. Whenever possible, evaluation measures should be shared between collaborating organizations in order to reduce erroneous attributions regarding causes of successes and deficits in performance.

Renegotiation, Control, or Exit

If managers from each of the collaborating organizations are satisfied with the evaluation and decide that no response is necessary, the collaboration

will probably continue as before, with managerial attention once more focused on the operation phase of the relationship life cycle. Given the dynamism of today's economic and political environment, and the fact that learning occurs almost inevitably as a result of collaboration experience, evaluation will probably indicate either major or minor opportunities for adjustment. If the need for adjustment is large, and the bargaining agreement permits, managers can approach their partners for renegotiation of the relationship. Objectives of the renegotiation are identical to those of the negotiation stage. Psychological aspects of this phase are similar also, except that all parties to the negotiation have a better idea of the likely behavior of their counterparts in the relationship; these experiences supplement their organizations' culturally determined approaches to cooperation and collaborating, which influenced behavior during negotiation.

When renegotiation is not an option, or in situations in which more minor adjustments to the collaboration are indicated, participant organizations can use control mechanisms to influence the functioning of the collaboration. Control mechanisms can be invoked either to promote or to inhibit the collaboration's effectiveness.

Many relationships, especially between public organizations, are bounded by a specific time duration or for the purposes of accomplishing a joint project and dissolve when these criteria have been satisfied. If the relationship was not specifically bounded in this way, and partnership performance is unsatisfactory to a partner with sufficient bargaining power to terminate it, or if the environment has changed so radically that the collaboration is no longer relevant to the participants' strategic goals, the cooperative interorganizational relationship will end.

In relationships between public organizations, success or failure in the accomplishment of mutual goals can have effects on the sponsoring organizations and their relationships (see Figure 5-1). When organizations have even a remote possibility of future collaboration, the importance of an amicable exit should be clear, given the role of group relations in laying the groundwork for cooperation. Of obvious importance in the dissolution of interorganizational relations is the avoidance of unduly scapegoating a particular partner for its shortcomings. The role of responsible and factual systemic analysis of problems and widespread communication of both findings and corrective action taken cannot be overemphasized.

Other Factors

Culture Clash and Change

Differences in values, expectations, and behavioral norms of communication and negotiation impact the possibility of cooperation during any contact

between two organizations. Because corporate culture can be expected to exert a stronger effect on work behavior than either national or ethnic culture (Kotter and Heskett, 1992), cultural differences may be a factor in both domestic and international relationships between organizations. Thus, international relationships between organizations are more (but not exclusively) subject to the issues of difference that are present in any negotiated relationship between two or more organizations. Similarly, those who wish to improve the viability of domestic collaborations can apply much of the work regarding national and ethnic cultural differences.

In designing collaborations, then, managers should be well informed about a number of cultural variables that will impact relationship viability. Especially when more interdependent relationships are being considered, they should possess as much information as possible regarding their own organization's corporate and national/ethnic culture: which characteristics are relatively stable and which more ephemeral, how these characteristics might augment or impede achievement of strategic goals, and how members of other cultures view their own.

Leadership

Organization leaders play a critical role in the success of any collaborative relationship between two organizations in a number of ways. First, leaders' assessments of their strategic goals and the best ways to pursue these goals will constrain the type of partner sought, as well as at what point in an organization's and industry's life cycle such collaborations are pursued. Second, the personal styles and business philosophies of organizational leaders can play a critical role in initial negotiations of collaboration as well as the partner ultimately chosen. In this sense, leaders can be seen (at least partly) as manifestations of, and actors on behalf of, their own organizational culture. Whereas interpersonal compatibility among leaders may be a good indicator of success, this is probably so because it bodes well for the effectiveness of contact among the organizations they represent rather than because of their own working relationships. The leader is an important symbolic element of the organizational community, and the success of a relationship between organizations will depend on his or her clear communication of goals and expectations for the collaboration, as well as the strategic value of the collaboration. Such communication throughout all participant organizations will be critical to operational success (Kanter, 1994). Appreciation of the relationship among leadership, culture, management behavior, and ultimate performance can vastly improve an organization's chances of embarking on and maintaining a successful relationship with other organizations (see, for example, Burke and Litwin, 1992; Burke and Jackson, 1991).

Evaluation

Successful management of interorganizational relations must therefore often include the possibility of review and renegotiation of agreements regarding strategic objectives, investments, provision of other resources, distribution of ownership, and division of proceeds. However, in order to avoid conflict, the organizations must agree on measures of the outcome variables on which these decisions will be based before the collaboration begins to operate. New measures can be added to the relationship system during subsequent negotiations, and ineffective ones removed. This clarification of measurement systems supports circumspect and well-founded decision making regarding collaboration management. Once again, the paradox of control emerges as a challenge during the creation of performance measures that reflect the interests of all involved parties—measures should support the system, not choke it. Nevertheless, appropriately chosen measures can help to reduce the likelihood of inaccurate appraisals of poor or solid performance, as well as the perceptions of inequitable distributions of inputs and proceeds between the participating groups.

Intergroup Relations

Intergroup relations are typically examined and understood in the context of conflict and competition for scarce resources (e.g., Levine and Campbell, 1972; Alderfer, 1977; Rice, 1969). However, in the creation of collaborative alliances, organizations are attempting simultaneously to manage this competition and their shared or overlapping interests. The work of group relations theorists can contribute to the identification of phenomena that may help to overcome this challenge. For instance, organization members' perceptions of other organizations and their members can be expected to exert a strong influence on their abilities to cooperate with members of those organizations, as well as on their abilities to exploit opportunities and resources offered by those organizations. Although perceptions of members of other organizations as outsiders may be inevitable, at least in initial stages of contact, the experience of that "outsider-ness" can be either potentially threatening and undermining or potentially enhancing and thus valuable. Perceptions of outsiders can thus impact the viability of any collaborative endeavor undertaken by two organizations.

These perceptions can be modified or controlled in a number of ways. First, information about the potential benefits accruing to the organization as a result of the collaboration must be widely available. Second, dissemination of the performance indicators discussed above can help reduce what may be unfounded perceptions of discrepancy in cost-benefit yields, thus facilitating cooperation between group members.

Finally, Haunschild and colleagues (1994) have demonstrated that group

members' expectations about how contact with another group will impact their own performance exert a strong influence on the group's openness to reframing its identification to include another group. Wilder (1986) has indicated that biases against another group can be weakened by individuating outgroup members, encouraging cross-categorization (these objectives can be achieved by forming work groups that cut across previously existing boundaries between groups), introducing a common enemy or overarching goal (i.e., highlighting the strategic importance of cooperation between groups), and removing situational cues associated with group membership. Managers can thus shape the meaning of the collaboration by focusing on expected performance benefits, making structural and systemic adjustments to support the achievement of these goals, and removing cues that detract from cooperation.

Stresses on Boundary Role Persons

The paradox of vulnerability and maintaining a climate of trust, open communication, and information sharing while at the same time protecting the host organization's autonomy and security presents a challenge for executives charged with managing interorganizational relationships.

Those performing in boundary positions are also responsible to both constituents in their host organizations and to their counterpart boundary managers in other organizations. Negotiation and the transfer of information and other resources across organizational boundaries occur within a boundary transaction system (Adams, 1976), wherein actions taken by constituents within organizations, as well as those taken by boundary managers, can have effects on the outcomes experienced by both organizations. Synergies resulting from the relationship depend largely on an organization's openness to influence from its own employees operating in clearly defined boundary roles. If there is resistance to the exercise of this influence, the relationship will be effectively contained, and potentially valuable information will not be distributed throughout the organization.

Conditions for Failure and Success

Obstacles to the success of relationships between organizations are real indeed, but they are not insurmountable. Organizational leaders who hope to capitalize on the opportunities available through collaboration and also to develop their organization's reputation as a desirable partner should consider both conditions that lead to failure and those that contribute to success.

Conditions for Failure

- First and foremost, if there is insufficient clarity about goals and how to measure progress toward these goals, the relationship is doomed.

- Should power and control between the partners be imbalanced, the relationship is not likely to last; that situation would indicate that an acquisition or a dissolution of the arrangement is in order. It may be that, in certain matters, one partner has more power and control than the other. Such an imbalance in certain areas may be acceptable as long as the imbalance is favorable to the other partner in other areas.

- If one partner has more expertise, status, and/or prestige than the other, the relationship is likely to be short-lived.

- If one or more of the partners is overly confident and unrealistic about the future success of the relationship, believing that he or she has sufficient control over variables external to and within the partnership, then conditions are ripe for failure.

- If things change without contingency plans, especially for renegotiating the relationship, the partnership is likely to deteriorate. Flexibility is key.

- A lack of perceived equity in the relationship of any kind—a fair distribution of important jobs to both partnering organizations, for example—will lead to serious problems.

These six conditions are neither discrete nor complete. Nevertheless, they represent some of the most significant conditions for failure in interorganizational relations.

Conditions for Success

The most important condition for success in an interorganizational relationship is having a goal or a set of goals that is clear and achievable only through the cooperative efforts of both partners. Social psychologists who have studied intergroup competition, conflict, and collaboration point to the critical function of what has come to be called a superordinate goal—a goal that neither partner could achieve separately but by joining together they can.

It is also imperative that this goal or set of goals be measurable. The question that must be answered is, ''How will we know that we are making progress toward goal achievement, for example, a year from now?" Other important conditions include:

- A balance of power and control in the relationship—if one of the partners is too dominant, then the consequences are more like an acquisition,

- with one absorbing the other and the other as an entity essentially going out of existence

- Mutual gain—each partner benefits from the relationship; the gain for each may be quite different—e.g., one obtains needed technology, the other realizes significant cost savings—as long as both clearly benefit

- Committed leaders—when leaders of the partnering organizations demonstrate a strong belief in the efficacy of the relationship and show cooperative, collaborative behavior, others in the respective organizations are likely to follow suit

- Alignment of rewards—making certain that organizational members are rewarded for cooperating, for partnering-type behavior

- Respect for differences—like individuals, no two organizations are the same; organizational members must therefore work hard to overcome biases and stereotypes and be rewarded when they do

- Good luck—things change, and partnering organizations sometimes have some control over the changes and sometimes not; a natural disaster can, for example, destroy a budding joint venture in agriculture. Thus, the importance of contingency plans and maintaining a degree of flexibility and a willingness to renegotiate is clear.

Unanswered Questions

If recent newspapers and magazine articles are indicative, the trend toward some form of interorganizational relationship will continue and probably even increase. More and more industries, especially the mature ones (e.g., chemicals, pharmaceutical, banks, etc.), are consolidating and therefore many additional mergers and acquisitions can be expected. There also appears to be a growing reliance on other, less permanent forms of relationships, such as networks and alliances. If this shift from a more permanent relationship (e.g., merger and acquisition) to less permanence (e.g., network, consortium, or alliance) is indeed true, why such a shift? Understanding more about this trend would be an excellent research agenda.

Assuming a shift to less permanence in relationships, two reasons to examine them via research present themselves. First, experience with and observation of a number of organizations suggests that most mergers and acquisitions prove to be unsuccessful, and economies of scale and promised synergies are not realized. The two (or more) cultures remain untouched and, eventually, what looked like a promising synergy becomes a disappointment. Why enter a relationship that is likely to be unsatisfactory? With consolidation occurring in many industries, ultimate survival is a primary reason. Also, mergers and especially acquisitions mean that more control by senior executives can be exercised. These are strong attractions for permanent relationships. Understanding these different dynamics—that

is, why mergers and acquisitions continue unabated when a successful outcome is questionable—would be a useful addition to our knowledge of interorganizational relations.

Second, to compete effectively in a turbulent, global marketplace, to keep the peace in a volatile society that may be falling apart, or to consolidate resources in a city that is losing industries and key professional and technical people, organizations today have to be highly flexible. Decisions must be made quickly and then perhaps changed in a matter of months if not days. This growing need for rapid decision making and adaptability flies in the face of permanence.

Research is needed, particularly research that is based on methods of rapid data gathering and analysis, to gain a better understanding of these trends and how ongoing they are likely to be.

In her review of key articles in the literature, Auster (1994) proposed five more specific needs for future theory and research: (1) conceptual clarity, (2) broadening units of analysis, (3) expanding the time frame of analysis, (4) investigating the complementarity of structure and process, and (5) expanding levels of analysis. These five areas for further study suggest rather clearly where the gaps are in the research literature so far, and consequently where more research is needed. Practice has outrun theory and research in this field, and there is a growing mountain of popular books and articles on strategic alliances, joint ventures, and the like. These publications can suggest executives' concerns and important areas for research. This literature is built largely on anecdotes and consultants' experiences. Scholarly research can subject many of these ideas and beliefs to systematic evaluation.

Conclusions

The discussion in this chapter suggests the following conclusions:

- The success of firms may be tied to how well they are linked with other firms in their environment. Industries like tobacco, pharmaceuticals, and electronics are profitable in part because competitors collaborate, within legal limits, in pursuing issues of common interest.

- The performance of an organization may be linked to its position in a network of relations—whether, for example, it is able to tap into networks for information or whether it is relatively isolated.

- The best unit of analysis for research on business performance—especially in Asia, some parts of Europe, and in highly networked industries like biotechnology—may be the network and not the individual firm.

- Organizations typically enter into alliances either to accomplish a goal that cannot be achieved alone or to distribute costs.

- Successful collaborations are the result of a well-managed process that is negotiated through predictable stages, from a preengagement state, to an evaluation stage, and possible renegotiation or exit from the relationship. The chances of success are increased to the extent that the process passes through all of these stages.

- Collaborations are more likely to fail when goals for the alliance are not clear or measurable, when there is a power or expertise imbalance between the organizations, and when organizations are inflexible in the face of changing circumstances.

- Political and military organizations are often forced to collaborate with partners for reasons other than the choice of organizational leaders. Research is necessary to understand how best to prepare these organizations and their personnel for alliances and alien forces, states, and organizations that may be very different culturally and operationally and with whom they do not have a predisposition to ally.

- Research is needed to understand the conditions for successful collaboration between nonmarket organizations in which financial measures of success are not available and issues of ideology and mission are especially salient in the overall political environment or context.