7 Conflict Management Training for Changing Missions

Our analysis of the Army's new missions calls attention to the kinds of skills that are needed to conduct them effectively. In this chapter, we identify the combat and contact skills needed for peacekeeping and operations other than war (OOTW) activities, then review current military training programs for the applicability of their skills training to mission requirements. Training programs worldwide devote relatively little time to the development of contact skills. We therefore propose a number of ways to improve conflict management training for particular missions. We also discuss factors that limit the effectiveness of this kind of training, interfere with the evaluation of the training, or limit mission effectiveness.

Preparing For Operations Other Than War

Combat and Contact Activities

A useful way to think about needed mission skills is to make a distinction between those used in combat operations and those involved in contact with individuals and groups. By combat skills, we refer to basic military skills used in situations in which there is a physical threat, weapons discharge, combat engagement, or internal security operation. By contact skills, we refer primarily to communication skills involved in exchange and liaison duties, interviews and public relations, negotiations and related discussions, civil-military cooperation, mediation of disputes, and interagency cooperation. Missions are likely to differ in terms of their mix of combat and contact activities; they also differ according to the rank and duties of the

military personnel involved in the operation. A chief difference among missions is whether the soldier's role is that of primary party or third party, as shown in Figure 6–1.

A recent survey conducted by the Lester B. Pearson Canadian International Peacekeeping Training Center (Last and Eyre, 1995) used the distinction between combat and contact activities. Canadian soldiers in the Bosnian (N = 197) and Croatian (N = 185) United Nations (UNPROFOR) operations were asked a number of questions about their experiences during the time period November 1993 to April 1994. Ninety-six questions, arranged in nine groupings, were asked of samples at three ranks: enlisted soldiers, noncommissioned officers (NCOs), and officers. Of these, 50 questions were relevant to the combat-contact distinction: 32 deal with combat activities, 18 with contact activities. From the answers, profiles were constructed for each operation. These profiles show the relative balance of combat and contact experiences for the two missions and how these experiences vary by rank.

The results show that combat skills are important at all levels, but that contact skills are more significant with increasing rank. The proportion of combat and contact experiences for the enlisted and NCO ranks was roughly equal for both operations. Officers reported about twice as many contact (about 40 percent) as combat (20 percent) activities in the Bosnian operation and almost three times as many contact (40 versus 15 percent) activities in the Croatian operation. The most frequent combat experiences reported were being a target for rocks thrown, encountering mines, coming under small-arms fire, being restrained, and being held at gunpoint. The most frequent contact experiences reported were working with interpreters, negotiating with civilian police and belligerent factions, and interacting with local civilians.

With regard to activities involving negotiation, almost all officers and many senior NCOs reported experiences with a soldier or officer of one of the warring factions; only 29 percent of the enlisted group reported having these experiences. A smaller percentage of officers (60 percent) reported negotiating with civilian leaders of one of the factions; an even smaller percentage of the enlisted group reported these experiences (about 15 percent). With regard to mediation or conciliation, about 50 percent of the officers and senior NCOs had these experiences, compared with only about 10 percent of the enlisted soldiers.

This leads to the conclusion that developing contact skills is clearly essential for officers, and it may be important to develop them even at the lower levels. It is also apparent that contact skills are increasingly important in many of the newer operations other than war. In traditional peacekeeping operations, only senior officers could be expected to have direct interactions with the protagonists and thus require some contact skills. Junior

officers and enlisted personnel might never have to use such skills, as they might be stationed as part of an interposition force in an area of low population density (e.g., the Sinai Desert). Operations other than war such as election supervision and humanitarian assistance require military personnel at all levels to be prepared to interact directly with the local population, perhaps on a daily basis.

If contact skills are important, then it is important to know to what extent training programs emphasize these skills. The Canadian survey is a first attempt to document what is actually done in OOTW missions. Nevertheless, it is largely limited to one type of mission, which we referred to above as limiting damage. The survey documents that these missions are characterized by a mix of combat and contact experiences and that the relative emphasis on these skills varies for the different ranks. These types of missions may consist of more combat activities than monitoring missions and more contact than coercive missions. The different missions may also entail different mixes of contact and combat skills in the training packages for the different ranks. Such comparisons await the results of similar surveys conducted in conjunction with other types of missions. The Canadian effort is a useful model for those surveys.

Training Programs

The combat versus contact distinction can also be used to depict what is being done in programs that train military personnel for operations other than war. The committee considered 79 programs worldwide that are summarized in a September 1994 training catalog issued by the Inspector General's Office of the Department of Defense (DoD). The catalog is divided between U.S. and international (33 countries) training activities; the U.S. programs are further divided into DoD (and its separate services) and non-DoD programs. Following a general description of the program, the specific topics taught in courses or addressed in roundtable discussions are listed. For example, elective courses dealing with peace operations at the Army War College are listed as "collective security and peacekeeping," "peace operations exercise," and "conflict resolution and strategic negotiation." Examples of subject areas included in the training packages at the Army Command and General Staff College are "non-combatant evacuation,'' "humanitarian assistance/disaster relief," "combatting terrorism," and "arms control." This information was used to assess the extent to which the programs emphasized the training of contact and combat skills.

Using keywords to identify contact skills, we calculated a ratio of the number of contact to combat skills included in each program's training curricula.1 The ratio consisted of the number of contact skills divided by

the total number of topics listed for each program. The results of this analysis indicate:

- Across the 79 programs, including both U.S. and international, an average of 13 percent of the topics or activities listed involved contact or interpersonal skills.

- For the 59 programs in which at least one contact skill was mentioned, an average of 25 percent of the topics involved the use of contact or interpersonal skills.

- There is little variation among the programs in terms of the number of contact skills included, with a range for most programs from 0 to 5 (or 0 to 25) percent. There is little difference between U.S. and foreign programs, nor is there much difference between the DoD and non-DoD programs or among the programs sponsored by the different services.

- The program that includes the most contact skills—five—is conducted by NATO. The program with the highest percentage of contact relative to combat skills is the U.S. central command.2

- With regard to the total number of skills being taught, there is considerable variation, with a range from 0 to 21. Among the more encompassing programs are the Air Command and Staff College (21 skills), NATO (16), Uruguay's Navy course (15), the United Nation's military observer training in the United Kingdom (14), the United Nation's soldier training courses (14), and specialized training in the Philippines (14).

Taken together, the results of the two analyses make it apparent that a gap exists between the skills being trained and the activities that occur in peacekeeping and related missions. Fetherston also recognized this gap, noting that "at best only a small fraction of course time is spent on [conflict resolution or cross-cultural orientation skills]—approximately 5 percent in any of the programs [that devote the most teaching hours to contact skills], either national or regional" (1994:208).

There is a diversity of opinion among U.S. military and foreign officers about whether traditional military skills are sufficient for most operations other than war. Nevertheless, it is evident that current training programs are skewed more in the direction of the view that combat skills are adequate for most personnel, regardless of mission. Yet it is apparent to the committee that a significant gap in the training of contact skills exists. The gap is accentuated further by uncertainty with regard to which skills are most pertinent to which types of missions. Having reached this conclusion, however, leads to the questions of what specifically should be trained and how the training should be done. These questions are addressed in the sections that follow.

Developing Contact Skills

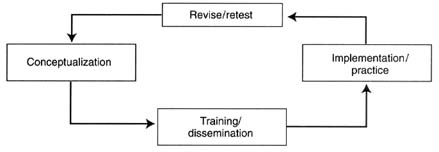

There is a large literature on approaches to developing communication and related interpersonal skills. Fetherston (1994) considered training issues in the context of theory and practice—she views training as a critical link between them. She depicts the link in terms of a cyclical framework in which "conceptual analysis leads to developments in training which lead to changes in practice. … (T)hese changes then initiate testing and revising which finally feed back into the conceptualization process" (1994:164-165). The process is visually represented in Figure 7-1. She illustrates the links with examples from cross-cultural training and concentrates on skills and attitudes that relate to effective interactions between members of different cultures.

Drawing on a review of literature by Hannigan (1990), Fetherston emphasizes the general communication skills of listening, entering a dialogue, initiating interaction, dealing with misunderstandings, language, and interaction management (see also Harbottle, 1992). She notes that although subject-matter expertise is important, it is insufficient without these communication skills. These are also the skills needed for effective third-party intervention in general. The review of literature also identifies attitudes that relate to cross-cultural effectiveness. In addition to positive attitudes and respect for the host culture, she notes that "a critical aspect of intercultural interaction [is] to be able to judge when it is best to be flexible and when it is better to be persistent" (1992:168). This is also a critical aspect of all international negotiations, as illustrated in the recent collection of papers on flexibility edited by Druckman and Mitchell (1995).

With regard to approaches used in developing these skills, Fetherston distinguishes among six types of training methods: fact-oriented training,

FIGURE 7-1 Cyclical development of the theory and practice of peacekeeping. Source: Fetherston (1994:165). Copyright A.B. Fetherston. Reprinted with permission of St. Martin's Press, Incorporated.

attribution training, cultural awareness training, cognitive-behavior modification, experiential learning, and interactional learning. She agrees with an earlier judgment made by Grove and Torbiorn (1985) that fact-oriented training is inappropriate because it does not allow for changes in one's usual patterns of interacting with others. These authors favor experiential learning because of its emphasis on learning through actual experience, allowing the trainee to notice the impact of his or her behavior on others.3 That impact is likely to be understood better if the trainee can internalize the host's values, which is a goal of attribution training (see Brislin, 1986; Danielian, 1967). Indeed, it is likely that a combination of methods works best.

Although it is important to develop general communication and interaction skills, it is also necessary to know when to use them. Some skills may be more useful for certain types of missions or for certain stages of a particular mission. Insufficient attention has been paid to this issue, due at least in part to a lack of differentiation among missions or among stages of missions. With regard to missions, the taxonomy described above contributes to distinctions among types of missions. With regard to stages, Fisher and Keashly's (1991) contingency model of conflict escalation, refined further by Fetherston (1994), has implications for thinking about developmental processes within peacekeeping missions. (See also Grove and Torbiorn's [1985] adjustment-cycle model of cross-cultural experience, which is discussed below.) And with regard to developing specialized skills, Johnson and Layng (1992) present an approach that builds skills that can be elicited in response to specific occasions or challenges.

Focusing on the conflict process, Fisher and Keashly (1991) developed a typology of conflict escalation that distinguishes among four stages: discussion, polarization, segregation, and destruction. At each stage, the relationship between protagonists changes significantly. The preferred method of conflict management by the parties themselves becomes increasingly competitive, going from joint decision making in Stage 1 to outright attempts at destruction in Stage 4. Intervention activities also change in terms of goals and intervention strategies: assisting communication through negotiation in Stage 1, improving relationships through consultation in Stage 2, controlling hostility through muscled mediation in Stage 3, and controlling violence through peacekeeping in Stage 4. (See the summaries in Fetherston, 1994:Appendices 3 and 4.) Interestingly, peacekeeping is used in this model only after a conflict has escalated to a destructive stage.

These models describe developmental processes. Each specifies the conditions under which certain processes are likely to occur as well as the intervention or training strategies that are appropriate. The Fisher and Keashly (1991) model links intervention approaches to steps on a ladder of escalation. Grove and Torbiorn (1985) link training methods to periods of adjustment.

These are complementary models. The former has implications for the military mission; the latter addresses issues that are relevant to the individual soldier. Both models are useful for identifying the kinds of interventions or adjustment problems for which training is needed. Neither model suggests, however, how the training or preparation ought to be done.

Guidance for training programs is provided by the research literatures on cross-cultural training and on conflict management. Fetherston (1994) reviews the literature on cross-cultural training and communication skills, and, as we noted above, uses this work as an example of linking theory with practice. She devotes less attention to the research on conflict management strategies. That body of research is also an example of linking theory with practice and deals with third-party intervention strategies in a more direct way than the cross-cultural training research. Of course, these skills have broad applicability, allowing us to draw on a large research literature for relevance to OOTW missions.

Conflict Management Training

Training in conflict management skills is recognized as an important part of preparation for peacekeeping and other OOTW missions. Despite the absence of these skills that we noted in many of the training programs worldwide, there is a noticeable trend toward incorporating units on negotiation and mediation in courses at the United Nations and at various military colleges and training facilities in the United States and Canada.4 One of the more systematic approaches to the training of negotiation skills is the course designed by the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations. Its training strategy covers four aspects of negotiation: its aim, the principles of negotiation, the elements of negotiation, and negotiation phases (including preparations, negotiation proper, closing, and reports and follow-up). Using a mix of lectures and role-playing exercises, the trainers provide advice about how to negotiate, and the trainees experience the process and the impact of their moves on that process. The advice given is to proceed in steps. With regard to the negotiation proper: start with tension-reducing gestures, understand all parties' limits of concession, narrow down differences, use persuasive skills, be correct and impartial, and request renewed negotiation.

Although such training is useful, it does not link the training to distinctions among types of missions. Nor do the programs distinguish among the missions in terms of primary versus third-party roles or distributive versus integrative relationships. Making these distinctions would tailor training to the kinds of skills needed for particular missions. To further improve the training programs, we suggest the use of up-to-date material and progressive in-class simulations.

First, we suggest that the classroom material presented to the soldier be brought up to date, so that it reflects the current state of knowledge in the field. The current material is quite dated, having a strong orientation to distributive and primary-party processes. Also, mediation and other third-party processes were at times confused with negotiation. Second, we suggest that in-class training be more extensive as well as varied and attempt to equip the soldier with a broad set of contact skills. The ideas here are quite basic: a soldier learns by doing, and the more varied the practice, the more flexible and effective the soldier will be (see also Druckman and Bjork, 1994:Ch. 3).

We suggest a confidence-building approach to skills acquisition. For some specific examples, consider primary-party (negotiation) training. It should move from a simple arena to a more difficult one—for instance, from negotiations over a fixed sum to negotiations with integrative potential. There could be one-trial negotiations, followed by multiple trials. Initially, issues could be simple, followed by negotiations over more complex issues. Some issues could be on divisible items, others not. With such progressions, the negotiations can be moved from simple to more complicated arenas, giving the soldier not only negotiation experience but also experience in increasingly varied and difficult contexts. In terms of other relevant forms, the negotiation experiences could move:

- from low emotion issues to high emotion issues,

- from familiar (car purchase) to unfamiliar negotiations (Dutch auction),

- from no alternatives to the negotiation to both sides having alternatives,

- from no power difference to high power difference,

- from no constituencies to multiple constituencies,

- from one opponent to several opponents, and

- from an ethical to an unethical opponent.

We suggest a similar approach for teaching the soldier third-party (mediation) skills. Initially, the soldier needs to be exposed to current knowledge on mediation and schooled as to when third-party versus primary-party approaches are required. Subsequently, the soldier should participate in increasingly varied and difficult third-party simulations. Specifically the simulations could move:

- from conflicts over one issue to conflicts over multiple issues,

- from conflicts with fixed outcome solutions to those with integrative solutions,

- from conflicts with two parties to those with multiple parties,

- from conflicts in which there are no alternatives to ones in which disputants have multiple alternatives, and

- from mediations requiring no strategies to those that do.

The conflict management research that would be drawn on for this instruction is divided between studies that deal more with distributive issues or bargaining processes and those more relevant to integrative or problem-solving processes. These are distinct approaches to negotiation, one primarily tactical, the other problem solving. As such, they can be thought of as techniques used to train negotiators. In the following sections, we describe these approaches, summarize key studies, and note both strengths and weaknesses with each approach, including attempts made to evaluate them.

Distributive Processes

Recall that our scaling exercise produced two dimensions along which the 16 missions were categorized. One was the distributive/integrative dimension and the other was the primary/third-party dimension. Consider now the distributive end of the first dimension. The emphasis of this approach is on moving an opponent to one's own preferred position. To the extent that tactics can be scripted or consist of procedures that are easily learned, the approach is somewhat mechanistic and manipulative, focusing on what the soldier can do to move the other party toward his or her desired outcome. The bargaining literature (both popular and academic) is replete with descriptions of various tactics that are intended to be used to influence the other to accept one's terms in competitive situations.

This approach is suited to missions in which adversarial parties are clearly defined, gains and losses to the parties can be calculated, the main goal is to achieve a settlement (rather than a longer-term resolution), and efforts are not made to turn over control (in the short term) to the disputing parties themselves. Examples are collective enforcement, preventive deployment, pacification, and antiterrorism. In addition to the combat skills needed for these missions, the soldier, in the role of primary or third party, is often faced with highly partisan disputes that require hard bargaining. The research literature suggests a number of bargaining tactics that can be used to encourage settlements of competitive disputes:

- Concede first on small issues, using this to make the case for later reciprocation by the other on larger issues (Fisher, 1964; Deutsch et al., 1971);

- By conceding less and infrequently early in the negotiation, a bargainer creates expectations for agreements on his or her terms (Druckman and Bonoma, 1976);

- Commit yourself to a position by presenting clear evidence that indicates you cannot offer any more concessions (Schelling, 1960);

- Persuade the opponent of rewards in making concessions, making it clear that the concession should not be viewed as compromising a commitment to a larger principle (Schelling, 1960);

- Increase the size of a demand after tabling a concession (Karrass, 1974);

- Take actions that prevent the other from losing face. Face loss often leads to rigid positions, even those that incur material losses (Brown, 1977);

- Propose a deadline to force action especially when the terms on the table are favorable (Carnevale and Lawler, 1986);

- Develop acceptable alternatives to negotiated agreements. They reduce a decision-making dilemma in the face of deadlines (Fisher and Ury, 1981);

- By shifting the talks to higher levels, the bargainer can relieve his or her reluctant adversary from taking responsibility for making the needed concessions (Druckman, 1986); and

- By avoiding the appearance of being tactical, the negotiator may avoid imputations of mistrust and antagonism (Snyder, 1974).

Among its strengths, this approach is based on a large body of empirical research dating from Siegel and Fouraker's 1960 book on bargaining behavior. Their work provided a paradigm for experiments on the impacts of alternative concession-making strategies on outcomes. Important reviews of this literature are Walton and McKersie (1965), Kelley and Schenitzki (1972), Rubin and Brown (1975), Pruitt and Kimmel (1977), Hamner and Yukl (1977), and Pruitt (1981). A recent meta-analysis illustrates the cumulative nature of the studies and distinguishes among strong and weak influences on bargaining behavior (Druckman, 1994).

Among the problems with the distributive approach are that it (a) assumes the "other" is receptive or responds in a passive manner to one's use of tactics, (b) says little about whether the other is playing a similar or different tactical game, (c) has little to say about continuing or repeated interactions among the parties or their relationships, (d) reduces opportunities for creative problem-solving by focusing only on the distributive issues, (e) ignores the deeper sources of conflict that may overshadow the interests at stake, and (f) may leave parties feeling that they fell short of their goals or leave them with the uncomfortable feeling that they were manipulated or manipulated the other party into accepting their positions. Furthermore, by encouraging intransigent posturing, this approach provides few incentives that would encourage the other to be flexible.

Many of the self-help books and seminars approach negotiating from the viewpoint of the tactician bent on maximizing returns. Popular examples are the books written by C. Karrass (1974), G. Karrass (1985),

Cohen (1980), and Nierenberg (1968). These books are used often as texts in seminars conducted by the authors. One well-known seminar titled "Negotiate to Win" highlights strategies for getting the best deal in competitive situations (Cooper Management Institute, 1993). Using role-playing exercises, the trainer provides opportunities for seminar members to experience the "seven commandments of good negotiating": trade every concession, start high, make smaller concessions especially at the end, "krunch" early and often (with examples of how to do this),5 be patient, nibble at the end, and look for creative concessions to trade. When these well-known tactics are taught, trainees are alerted to the importance of face-saving and the need to create a positive atmosphere through the use of "soft'' language.

Unfortunately, few attempts have been made to evaluate effects of the training on negotiating performance over time. Nor are the trainers favorably disposed toward such evaluations—when asked about evaluations, trainers often remark that their success is indicated in the marketplace, where subscribers "vote" and profits result. Little thought goes into whether the training improves performance. Considerable attention is given to ways of marketing the seminars to attract new customers. Although accepting the distributive bargaining approach, these trainers largely ignore the insights from the research studies cited above.

Integrative Processes

The emphasis of this approach to training is on a search for high joint-payoff solutions that endure. Bargaining is eschewed in favor of creative problem solving. A premium is placed on establishing a cooperative atmosphere, on acknowledging the other's plight or the reasons he or she takes particular positions, and on diagnosing the sources of conflict, rather than executing tactics to win.

Some of the features of this approach involve the way roles are defined and the kinds of behavior that is enacted:

- The approach is less concerned with settlements than with enduring resolutions and improved relationships.

- While searching for sources of conflict, the parties also identify factors that aggravate the conflict or contribute to tensions among themselves.

- While emphasizing process activities, the approach recognizes the importance of a thorough understanding of the substantive issues at stake.

This approach contrasts to the distributive bargaining approach in several ways: (a) it focuses on conflicts that result primarily from misunderstandings and stereotyped perceptions rather than interests, (b) it seeks to create relationships based, at least to some extent, on interdependence, (c) it

emphasizes the importance of developing mutual trust, (d) it assumes that positive interpersonal relations (and understanding) will produce enduring resolutions of the conflict, and (e) it downplays the fact that many conflicts are matters of interest resolved through compromise rather than by finding integrative solutions.

This approach is suited to missions for which the parties (which often include the local population) have common goals and seek to prevent further losses, the main goal is to achieve long-term solutions or stability, and attempts are made to turn the situation over to the local population as soon as possible. Examples are disaster relief, election supervision, aid to domestic populations, and in some respects, observation. These missions are characterized less by conflicts of interest than by conflicts over the best way to solve the common problem confronting the population. Challenges include organizing the local population, coordinating with nongovernmental organizations, and knowing when to turn the operation over to the local population. The contact skills needed to meet these challenges are those discussed in the literature on integrative problem solving.

Although the research to date on integrative processes has been limited, there are some significant studies that have identified conditions for effective problem solving. For example, with regard to negotiators, Carnevale and Pruitt (1992) found that problem solving is more likely to occur when negotiators show significant concern for the other's outcomes as well as their own, when the parties exchange information about their underlying priorities and needs, and when both sides are convinced that their conflict has integrative potential (outcomes that are best for all parties). With regard to a mediative process, Kressel and his associates (1994) identified a problem-solving (integrative) style that contrasts with a settlement-oriented (distributive) style. The former was a more active approach that progresses through stages involving searching for the sources of conflict, generating hypotheses and diagnoses, and shifting responsibility to the disputants for generating and feeling a sense of ownership for solutions. It produced more frequent and durable outcomes than the settlement-oriented style, even though it was used less frequently by the participants in their study. It also produced a more favorable attitude by disputants toward the mediative experience. (Mediative processes are discussed below in the section on the third-party role.)

Among its strengths, the integrative approach identifies the skills needed for a satisfactory and lasting solution to conflicts.6 By emphasizing the cognitive demands of problem solving, the approach calls attention to the realization that there are unlikely to be quick fixes to the resolution of conflicts. It includes skills useful for negotiators as well as those needed by mediators, whose goal is to achieve a constructive resolution of conflict. Included among those skills is the need to defend oneself against unwarranted

accusations or anger directed at oneself as well as the detection of bluffing (Druckman and Bjork, 1991:Ch. 9).

Among its weaknesses, the approach does not distinguish between sources of conflict (interests, values, needs) and factors in the situation that aggravate the conflict (e.g., competitive orientations, hardened constituencies, simplified images, media coverage). It assumes but has not demonstrated that improved interpersonal relations and understanding lead to enduring resolutions. This may be particularly critical, in that some operations other than wars will be deployed when conflict participants have relatively clear perceptions but fundamental and perhaps irreconcilable differences in interests or preferences. Furthermore, efforts have not been made to distinguish between general and situation-specific third-party skills, and little has been done regarding the transferring of resolutions achieved with small groups to other groups or organizations.

With regard to practical contributions, the approach gained popularity with the 1981 publication of Fisher and Ury's Getting to Yes (see also Fisher et al., 1991). These authors called attention to deeper interests than those revealed by the positions of disputants in negotiation. In a sequel, Fisher and Brown (1988) emphasized the importance of relationships, making the distinction between agreements that may serve immediate needs and relationships that may be either helped or hindered by the negotiation process. Carrying this theme further, Saunders (1991) stressed the importance of developing international relationships as a goal of foreign policy decision making. The relational theme in international relations has gained momentum in post-cold war theorizing, largely as a reaction to realist approaches (Stern and Druckman, 1995). It is central to problem-solving approaches to conflict management and to the debate about participation in OOTW activities.

The approach is also reflected in various attempts to deal with deep-rooted conflicts between nations and ethnic groups. A set of techniques, referred to loosely as the problem-solving workshop, has evolved from early versions (Burton, 1969; Doob, 1970; Kelman, 1972) to refined interventions with strong claims for effectiveness, especially in the context of the Middle East conflict (e.g., Rouhana and Kelman, 1994) and elsewhere (e.g., Fisher, 1994). Little has been done to advance a methodology for assessing its impacts, so we must rely on the claims made by the authors. Until more progress is made, we should suspend judgment about the utility of the approach both with regard to its effectiveness in handling interpersonal or intergroup conflicts and in transferring the results of the intervention to other segments of societies. We address issues of evaluation of training programs in further detail below.

We now consider approaches to training that deal with the other dimension shown in Figure 6-1: the distinction between the primary-party and

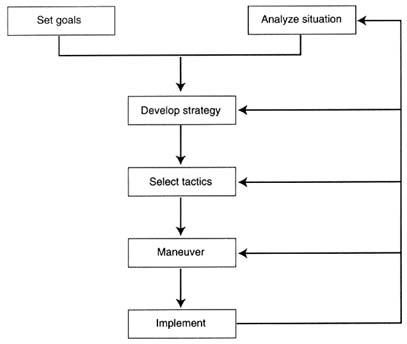

FIGURE 7-2 Strategy development.

third-party roles. In the former role, the soldiers deal directly—somewhat one-on-one—with other individuals or groups. By contrast, in the latter role, the soldiers must orchestrate the interactions between two or more groups and attempt to improve them. Quite different skills are required in each role, and we delineate these in the following sections, relying on a decision-making model (Figure 7-2). Consider first the primary-party role.

Primary-Party Role

Goal Setting

In primary-party missions (e.g., disaster relief, collective enforcement), the soldier must control or modify the other parties' (or group's) behavior in some fashion. A simple example is having individuals line up to receive water allocations; a complex example is having a hostile army withdraw from occupied territory (Abizaid, 1993).

When attempting to control the other parties, the soldier has limited power and consequently cannot prescribe the behavior of others, ignoring

their preferences, goals, ideas, values, etc. Rather, he or she must negotiate and plan to operate from a limited power base. Specifically, the soldier must define his or her aspirations, which are the net outcomes (benefits minus costs) that are expected or sought from the interaction or mission (for example, 200,000 people fed for 3 months with no loss of soldiers' lives at a cost of $10 million, using 1 battalion of troops.)

Such goal setting also consists of developing limits or fallback positions beyond which the soldier will not budge. The soldier could possibly seek to maximize his or her own payoffs without concern for those received by the other parties. Other possibilities exist; for example, the soldier could attempt to maximize the others' payoffs or the joint payoffs. Alternatively, he or she could simply improve the relationship with the parties, rather than raising anyone's outcomes.

Even though goal setting is the first step in a strategy, it must at times be quite fluid. On occasion, the available information is insufficient for establishing a goal. Or the original goal may be incorrect. Or the situation, as well as the behaviors of the various parties, may change radically. Or the mission or demands of superiors may be altered.

It is also possible for these latter determinants—mission and superiors' orders—to require that the goal be very rigid (D. Last, personal interview). In such a case, the soldier has the advantage of a stable goal but the disadvantage of inflexibility—not being able to revise goals as the situation dictates.

Situation Analysis

When choosing a goal and reflecting on the proper strategy, the soldier needs to perform an analysis of the situation, examining (a) his or her own position, (b) the other's (or opponent's) position, (c) the relationship between them, (d) the interaction process, and (e) the broader context within which those interactions occur.

When focusing on his or her own position, the soldier must determine which issues are more or less important: Does an issue have high payoffs or costs? Is it a matter of principle that the soldier feels should be important? Do the constituencies hold the issue to be of importance (Walton and McKersie, 1965)? Which issues can be traded (Pruitt and Rubin, 1986)?

While considering the issues, the soldier judges his or her aspirations as well as the initial offer and limit for each issue. This includes developing a rationale for the choices, possible trade-offs between issues, and the value to be placed on the relationship with the other parties. In weighing trades, a soldier may consider making compromises on issues that result in increasing trust and improved relationships with the other parties.

When making such judgments, the soldier must remember that a settlement is unlikely to occur if he or she fails to consider the others' reactions or the opponents' positions on the issues. Such reflections often require adopting the other's perspective (Neale and Bazerman, 1983); although this has been shown to be a difficult challenge (Johnson, 1967; Summers et al., 1970), it is worth the attempt. It includes deciding which issues are more or less important, getting an idea of the other's aspirations and limits, as well as their evaluation of relationships.7 For example, if the opponent has attractive alternatives and places a low value on the relationship, he or she is likely to be a tough bargainer; an opponent with limited alternatives and low aspirations will probably be more cooperative (Pinkley, 1995). Gathering information through monitoring the other's statements and proposals is an important part of the bargaining process (Druckman, 1977, 1978). It leads to the kinds of changes in expectations and adjustments of moves that can produce agreements (Coddington, 1968; Snyder and Diesing, 1977).

Strategy

With an initial goal and situation analysis in mind, the soldier develops or selects a strategy. This is the general plan for dealing with the others, whereas the tactics are the specific steps (Wall, 1995). A strategy can range from simple to complex. A simple strategy could be one of consistent force wherein the soldier brings in many troops, places them in strong positions, and then demands that the others withdraw (Abizaid, 1993). A second simple strategy could be one of reciprocity (Esser et al., 1990)—that is, making a concession. If the others reciprocate, the soldier makes another, then awaits a reciprocal concession. If the other party plays tough, making no concessions, then the soldier does likewise. A third strategy is to place the burden of concession making on the other by refusing to compromise. Some implications of these exchanges are demonstrated in experimental studies (e.g., Axelrod, 1984).

A more complex strategy is the bluff-twist (Wall, 1995). Here the soldier begins the bargaining with a bluff that he or she knows the other will call. As the other calls the bluff and overextends himself, the soldier cuts the other's line of retreat, as well as the alternatives, and then exploits the other's vulnerability.

Strategies, simple or complex, can be intended to raise the outcomes for both sides. For example, the soldier can attempt to expand the resources or negotiation scope so that both he or she and the other parties get more of what they want. The soldier can exchange concessions on different issues with the others, having each yield on an issue that has high payoffs for the other but low payoffs for him- or herself (Pruitt and Rubin, 1986). Or the

soldier can consider the underlying interests for him- or herself and the other party and develop ways to satisfy those interests (see Fisher and Ury, 1981, for a discussion of this approach).

Tactics

Strategies are developed and attained by piecing together different tactics, that is, the specific steps in the strategies. A large number of tactics are available to the soldier, falling into the broad categories of threatening, coercive, conciliatory, rewarding, posturing, debating, and irrational tactics (Wall, 1995). The negative tactics of threats and coercion are attempts to reduce the other's outcomes. These can be used early in an encounter, to reduce the others' aspirations, or late, somewhat as a last resort (Tedeschi and Bonoma, 1977). The positive tactics of conciliation and reward are attempts to improve the relationship and reinforce desired behavior (e.g., Tedeschi and Bonoma, 1977).

Posturing tactics are used primarily to alter the other's perception of the soldier's role and his or her behavior. Debate consists of problem-solving discussions and exchanges of information (Walcott et al., 1977). For example, the soldier notes the issues and tasks he or she would like to avoid (e.g., to whom God gave the disputed land) or uses logical arguments to convince the other of the merits of the approach. The irrational tactics are those that seem to give the soldier low outcomes or outcomes lower than alternative actions. Yet as the adage "crazy like a fox" suggests, sometimes these tactics can produce fine results.

Maneuvers

Maneuvers are steps to improve the soldier's position. Just as an infantry lieutenant moves his or her platoon to high ground prior to battle, the soldier can take steps to improve his or her position in personal interactions. These include steps to increase his or her own strength, to decrease that of the other, or to leverage the opponent. Efforts to increase one's own strength include stockpiling resources, building adequate hard force, and building alliances. Efforts to decrease the other's strength include closing off the opponent's alternatives, preventing the opponent from forming alliances, and reducing his or her stockpile of resources. The soldier can also leverage the other by attacking his or her weaknesses or by opening a discussion with a more pliant member of the opponent's team whenever one of the others is obdurate.

Implementation

When implementing the strategy, the soldier puts the plan into action with tactics. The keys here are timing and feedback. With regard to timing, some tactics must be used simultaneously and others in selected sequences. With regard to feedback, the soldier must observe the other's responses to his or her tactics and maneuvers. If the other is reacting as expected, the soldier can hold a steady course. If this is not the case, he or she must reconsider and perhaps modify the goals, analysis, strategy, tactics, and maneuvers.

Third-Party Roles

Here we need to reiterate a point made earlier: in some missions, the soldier acts more as a third party than as a primary party. In missions such as traditional peacekeeping, the soldier must, for the most part, control the relationship and interactions between two other groups. The skills required are quite different from those needed in the primary-party role; namely, they are more likened to mediation skills than to negotiation skills.

Goal Setting

When establishing the initial goal in a third-party mission, the soldier must orient him- or herself toward the relationship between the two interacting parties (e.g., the Bosnian Serbs and the Bosnian Muslims) and attempt to forge agreements or interactions between them that maximize their joint outcomes. Admittedly, the soldier must not lose sight of his or her own goals (e.g., safety of troops) and that of constituents (e.g., peace in the area), but the major goal is to improve the interaction between the parties.

Situation Analysis

When analyzing the situation, the third-party soldier must first determine if there is a conflict between the parties. Typically there is, and the soldier must develop skills in analyzing the causes and issues of the conflict.

Causes are often distinct from the issues, and many of the causes lie within the parties themselves (Augsburger, 1992), in their perceptions of each other, their communications, past interactions, and structural relationships (Putnam and Wilson, 1982). A party may have the goal of hurting the other or may simply be angry. Such feelings will generate conflict. With regard to perceptions, conflict is likely to occur whenever one party perceives the other side's interactions to be harmful or unfair. Interpersonal

communication leads to conflict (Putnam and Poole, 1987) when it entails insults or intentions to harm the other. Structured interdependence between parties who have opposite goals will quickly engender conflict. Because conflict has so many causes, the soldier must become adept at identifying the genesis of the current conflict and determining which ones can be addressed.

Soldiers must also understand the issues that are generating problems. When parties interact and come into conflict, it is usually over issues that are either large or small, simple or complex, emotional or substantive (Walton, 1987). Certain issue characteristics have been shown to generate conflict and thereby merit the third party's attention. One is complexity. Complex issues are more apt to lead to conflict than simple ones. Multiple (versus a few) issues also more often spawn conflict. The explanation in both cases is rather clear: complex and multiple issues are more likely to generate misunderstanding, tap divergent interests, and unearth dissimilar goals. Issues of principle or nonnegotiable needs also generate conflicts (Fisher, 1994; Rouhana and Kelman, 1994). On these last issues, parties become emotionally bonded to their positions, and once into conflict over them, they find that trades—reciprocal give and take—are quite difficult. Broad or intangible issues also tend to generate conflict and be less amenable to conflict resolution (Vasquez, 1983; Diehl, 1992). Because such issues entail high stakes and are often indivisible, the parties hold strongly to their positions and move toward conflict (Albin, 1993). Once in the conflict, the all-or-nothing characteristic of the issue makes palatable, face-saving, piecemeal trades quite difficult to arrange (Zechmeister and Druckman, 1973).

The soldier should address issues and causes that are of low cost to deal with and about which he or she has some knowledge. He or she should work with the opposing parties to solve complex issues, multiple issues, and issues of principles. Issues and causes that are intractable and minor should be ignored as long as possible. Also, the agenda should be arranged so that early agreement on simple issues and successful elimination of minor causes of conflict produce momentum for improved party relations (Fisher, 1964; Pruitt and Rubin, 1986).

Tactics

Having defined the overall goals for the mission and analyzed the situation, the soldier begins to develop a strategy and to select tactics. The literature on third-party processes reveals that the line between strategy and tactics is blurred (Carnevale and Pruitt, 1992) and that third parties, for the most part, rely on sets of tactics rather than major strategies to improve the parties' interactions.

When acting as a third party, the soldier has three targets for tactical behavior: (1) the parties themselves, (2) the interparty relationship, and (3) the soldier-party relationship (Wall, 1981).

- Conflicting Parties. In general, a soldier can take steps to move the parties off their current positions and to nudge them toward positions that are more agreeable to the other side. Such steps include:

- Help the parties save face when making concessions (Podell and Knapp, 1969; Pruitt and Johnson, 1970; Stevens, 1963);

- Help the sides resolve internal disagreements (Lim and Carnevale, 1990);

- Help them deal with constituents (Wall, 1981);

- Add incentives or payoffs for agreements and concessions (Kissinger, 1979);

- Apply negative sanctions, threats, or arguments (Kissinger, 1979);

- Propose agreement points that were not recognized by either side (Douglas, 1972); and

- Expand the agenda to find a larger arena in which rewards will be higher and costs lower to both sides (Lall, 1966; Pruitt and Rubin, 1986).

-

Interparty Relationship. When operating as a third party, the soldier's primary focus is on the interparty relationship and the goal is an agreement that will be implemented. In seeking these goals, the soldier may follow many routes. One is setting up the interaction: often the soldier discovers that the parties are fighting but not talking; there might be a stalemate in which there is neither talking nor fighting; or there could be an absence of interaction because some other third party has separated the parties and prevented their interaction (as in the case of traditional peacekeeping). In such situations, the soldier must often establish a negotiation relationship between the parties and stabilize the process. Doing so may require that the third party identify the membership of the opposing groups or their leaders and then bring the leaders to the bargaining table.

Having established the interaction and identified the disputing parties, the soldier next faces the task of enticing them to negotiate. Often this is a difficult task, because the parties do not like the negotiation format, they feel that negotiating is a sign of weakness, they believe negotiation gives some legitimacy to the opponent, or they believe negotiation puts them at risk in some way (Pruitt and Rubin, 1986). To overcome these and other obstacles, the soldier must discover the parties' objections, then discount or reduce them. Also, the outcomes from negotiating or interacting peacefully may be increased or the costs for refusing to negotiate raised.

- After initiating interactions, the soldier can establish the protocol for the negotiation process by suggesting and enforcing mechanisms through which the interaction will be conducted. These can be formal, specific agendas or somewhat more informal ones. In addition, he or she can inform each party as to what behaviors can be expected from the other side and advise each side on its own initial and responsive actions.

When establishing the protocol, the soldier can provide evaluations of the situation. In joint or separate meetings, he or she can enumerate and describe the important issues, interpret their complexity (or simplicity), note how similar problems have been handled, and provide data as to the costs of continued disputing (Lim and Carnevale, 1990). Once the interaction is under way, the soldier should channel the initial discussion toward an area in which he or she believes the parties can agree (Maggiolo, 1971). As both sides discuss this arena, the soldier needs to expand the agenda to bring in additional issues. When doing so the soldier should set up trades, in which one party gives in on issues that are of low value to it but of high value to the opposing side. As he or she facilitates such trades, the soldier must maintain the integrity of the interaction channel, enforce the protocol rules, and proscribe such behaviors as retracting offers previously made. At times, the soldier will find it necessary to separate the opponents (Pruitt, 1971). This separation allows him or her to sever, relay, or modify communications for the sake of productive negotiations. He or she might reopen the channels and bring the parties together if this is useful, forbid their interaction if it seems likely to incite antagonism, or create a formal schedule of meetings if such a mechanism proves useful. As the soldier severs and reconstructs the interactions, he or she can manage the parties' power relationship, a relationship that is of great importance to both the soldier and the parties. Typically, the soldier should strike a balance between the parties' total power positions. Doing so lowers the probability that the stronger side will attempt to exploit the weaker and that the weaker will break off the relationship or seek to undermine the stronger's position (Thibaut, 1968). If he or she cannot balance the power relationship, the soldier must bargain with or use hard force against the stronger side to constrain the exercise of its power. - Soldier-Party Relationship. To be successful in interactions with the parties, the soldier must gain their trust and confidence. Tactics with these goals are typically labeled ''reflexive" (Kressel and Pruitt, 1985, 1989) and include appearing neutral, not taking sides on important issues, letting the parties blow off steam, using humor to lighten the atmosphere, attempting to speak the parties' language, expressing pleasure at progress in the negotiation or conflict resolution, keeping the parties focused on the issues, offering new points of view, bringing in relevant information, and correcting one party's misperceptions.

- Using such techniques to develop trust and establish credibility is quite important (see also Harbottle, 1992). Without them, the soldier will have little leverage on the parties.

When utilizing these tactics—as well as many of the preceding ones—the soldier may find that he or she sacrifices the image of neutrality. This is not a major obstacle if the soldier demonstrates trustworthiness and effectiveness or if the parties feel that the intervention provides more benefits than costs.

Maneuvers

When operating as a third party, the soldier's options for maneuvering are the same as in the primary-party role: increasing his or her own strength, reducing that of the parties, or leveraging them. If the soldier attempts to weaken either or both parties, perhaps by closing off some of their options or by preventing them from forming coalitions, he or she risks generating resentment. Possibly one or both parties' retaliation may convert the third-party relationship into an adversarial primary-party affair.

Under some circumstances, the soldier might try leveraging the parties, that is, bringing his or her own strength to bear at a time or place that is to his advantage. (For example, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in the Yom Kippur war of 1973 delayed munitions shipments to the Israelis until they had only a one-day supply.) Nevertheless, this approach also risks their resentment and encourages retaliation.

Strategy

Currently, the literature does not provide adequate descriptions or prescriptions for third-party strategies. A strategy, in mediation as well as in warfare, football, chess, bridge, and organizational policy, is a broad plan of action for attaining some goal. For example, in a retreat-and-flank battle strategy, an army retreats when the enemy attacks in force. Once the enemy has extended itself, the army flanks the enemy, striking at one or more vulnerable points. Or in a simpler strategy, the football team for one quarter might establish a running attack and then shift to a mix of running and passing.

Note the ingredients in each of these strategies: goals, actions, and timing. Presently, the literature deals adequately with the goals and action components of third-party strategies but ignores the last element.

In this literature, one group of researchers (e.g., Carnevale, 1986; Carnevale and Henry, 1989; Kressel, 1972; Kressel and Pruitt, 1985, 1989; van de Vliert, 1985) describes third-party strategies as techniques (or tactics) that are oriented toward a similar goal. Specifically, Kressel and Pruitt (1985, 1989) hold that a reflexive strategy consists of techniques that orient the

third party to the dispute and establish the groundwork for later activities. A substantive strategy includes techniques that deal directly with the issues and actively promote settlement, whereas contextual tactics alter the climate or conditions between the disputants.

A second group of scholars in the literature (e.g., Carnevale and Pruitt, 1992; Kolb, 1987; McLaughlin et al., 1991; Silbey and Merry, 1986; Touval and Zartman, 1985) have taken a different tack, combining techniques that share conceptual or operational similarities (other than goal). For example, Silbey and Merry's (1986) typology contains four principal categories: (1) the third party's presentation of self and program, (2) its control of the mediation process, (3) control over the substantive issues, and (4) activation of commitments and norms. In a similar fashion, Kolb (1987), after in-depth interviews, laid out alternative strategies or postures that the third party assumed. She distinguished between helping and fact-finding corporate ombudsman roles: the helper invents individualized solutions to the problems people present, whereas the fact-finder investigates whether proper procedures were followed and if there are plausible explanations for a complaint.

A third group of researchers (Elangovan, 1995; Lewicki and Sheppard, 1985) classify the third party's techniques into strategies according to the target for control. In the group, Sheppard (1984) maintains that third-party strategic behaviors differ along two principal lines: decision control and process control. A third party's decision control is the management of the outcomes of the dispute. By contrast, process control entails control over the presentation and interpretation of evidence in the dispute. Elangovan (1995), relying heavily on Sheppard's concepts, generates five strategies:

- Means control strategy: the third party influences the process of resolution.

- Ends control strategy: the third party influences the outcomes.

- Full control strategy: the third party influences both.

- Low control strategy: the third party influences neither outcomes nor process.

- Part control strategy: the third party shares both controls with the disputants.

Finally, one group of investigators (e.g., Lim and Carnevale, 1990; Karambayya and Brett, 1989; Kim et al., 1993; Wall and Blum, 1991; Wall and Rude, 1985) have defined (and located) strategies as techniques that are used together by third parties when they deal with disputes. For example Kim et al. (1993), relying on a factor analysis, found techniques used together in four strategic combinations: reconciliation, dependence, analysis, and data gathering. In the "analysis" strategy, third parties were found to

rely on the techniques of getting a grasp of the situation, analyzing the parties, and capping the agreement with a handshake, meal, or drink.

The above four approaches deal quite adequately with the goals and action components of third-party strategies. And some of the literature (Elangovan, 1995) deals creatively with the contingencies under which the various strategies are or should be applied.

However, none of the approaches deals with the timing aspect of strategies. This omission is unfortunate, because timing is an essential element in any strategy. In a retreat-and-flank battle strategy, for example, when the army flanks and attacks, timing is essential. If it is either too early or too late, the strategy is a failure. Likewise, when a third party uses various sets of techniques is quite important.

Implementation

We propose a simple contingency strategy for third-party soldiers, based on two observations: (1) The effectiveness of most tactics is contingent on the situation and (2) we know more about what a soldier can do than we do about what is effective, at least given the current state of research findings (see also the discussion below on evaluating effectiveness).

The first observation dictates that the soldier should choose tactics that fit the situation. To date, we know that the following behaviors are likely to be effective in a wide range of situations:

- Separating aggressive opponents (Pruitt, 1971);

- Controlling the agenda and helping the sides to establish priorities among the issues (Lim and Carnevale, 1990);

- Adding control to the process (Prein, 1984); and

- Being friendly to both sides (Ross et al., 1990).

Other behaviors or tactics are more likely to be effective in some situations. Humor might be used when the soldier detects hostility (Harbottle, 1992). If there are many issues, the soldier should simplify the agenda and suggest trade-offs. When the parties lack bargaining experience, the soldier should educate them or note procedures that have been used in the past. And when the parties are able to resolve their own problems, the soldier for the most part should not intrude (Lederach, 1995).

The second observation suggests that soldiers should adopt a pragmatic approach. They should first try techniques that seem reasonable. If none of these works, then they should try a different one or a different set. Again, if there is failure, a new set should be put in place and the failure noted. This approach should be continued until the relationship and the outcomes between the parties improve. Most important, the soldier, in this process,

must be diagnostic, remembering what failed and what was successful for each episode; this is consistent with the experiential learning model discussed above. He or she should also use feedback in the process of evaluating and modifying the goals, tactics, and maneuvers.

This trial-with-memory strategy is proposed because currently there is a great deal of uncertainty as to which third-party tactics are successful. In addition, even if we know what was successful in general, techniques have to be fine-tuned to the situation, using an approach like the one just described.

Limitations Of Conflict Management Training

Even if training for operations other than war incorporated all the elements of integrative/distributive processes and primary/third-party roles at all ranks, there still exist several elements that may limit (in absence of countervailing action or training) the utility of that training or affect our ability to judge its effectiveness. Perhaps the most important of these is the influence of culture in conflicts and their management.

Cultural Impacts

While often acknowledging the importance of national cultures, scholars, practitioners, and trainers rarely develop the implications of cultural differences for the role of primary parties and intermediaries in the resolution process. Such deficiencies are unfortunate, because culture has major implications for any operation other than war. In most missions, the soldier is posted to and operates within cultures that are different from his or her own. In turn, these cultures impact on the soldier and determine how the various parties behave as they interact among themselves or with soldiers. In this section, we discuss some possible impacts of national cultures on soldiers, as distinguished from the organizational cultures discussed in Chapter 3.

Culture Shock

One of the major impacts comes from culture shock to the soldier. He or she is thrust into a culture that is often not understood and must work productively with parties whose behaviors, norms, and organizational structures are somewhat perplexing. The soldier may experience culture shock not only from dealing with a new locale and the surrounding population, but also from interacting with soldiers from other countries whenever the mission force or command is multinational. The reverse is also true: soldiers will have to deal with the effects of the culture shock experienced by the local population and multinational soldiers who themselves will be interacting with soldiers of different races, cultures, and approaches.

Grove and Torbiorn (1985) propose a four-stage adjustment cycle for people immersed in new cultures: a period of euphoria, culture shock, recovery, and completion of the adjustment process. For them, the stage at which culture shock is experienced is most interesting; it is the longest and most difficult period, and the one in which the least amount of learning occurs. This is the stage for which predeparture training is likely to be most useful for the soldier, and the programs should be aimed at reducing the severity and duration of this stage. Grove and Torbiorn recommend a training approach that includes a combination of fact-oriented and experiential methods aimed at achieving this goal. (A similar adjustment cycle was proposed earlier by Moskos, 1976, for peacekeeping operations. Although he also identifies a similar Stage II as the most important period, he disagrees with Grove and Torbiorn on the relative value of predeparture training versus field experience for facilitating adjustment.) It may also be necessary to include some soldiers in OOTW units who already have appropriate foreign language capability or a quick capacity for acquiring key phrases and elements of the local language, so as to minimize communication difficulties that exacerbate culture shock (Eyre, 1994).

Military-Civilian Impact

Closely accompanying culture shock is the impact of dealing with civilians. Soldiers, operating for an extensive period within a military culture, are accustomed to taking orders and conforming. They are healthy, well fed, well clothed, and regularly well paid. In short, they exist in a protective, orderly environment that has a great deal of structure. The civilian culture, especially those to which the soldier is likely to be posted, is quite different. It is frequently disorderly, and life for many civilians is very tentative; they are often sick, ill clothed, and paid erratically. Furthermore, civilians, for the most part, do not like being ordered about, especially by military personnel.

The impact of the military civilian divide is multifaceted, with one critical aspect being differences in goals. The soldier's goal of keeping the peace differs from the civilian's goal of staying alive and earning a living, and the simultaneous pursuit of these may generate conflict rather than peace. For example, roadblocks might be set up to keep one militant faction from having access to and attacking the other. The goal from a traditional soldier's perspective is to minimize conflicts, which will result in civilian, as well as military, casualties. This is a legitimate goal, but the farmer's goals might be more pragmatic—to get to his fields without waiting and to gain access to markets on the other side of the dividing line.

Another impact is that civilians often tend to dislike or distrust soldiers; therefore, soldiers in both the primary and third-party roles must vigilantly

monitor civilians' reactions to their presence and behavior. Often the most straightforward, nonassertive tactics can be misunderstood and resented.

Cultural differences in the context of a multinational mission may be something of a double-edged sword. The national cultures of some troops may be similar to those of the indigenous civilian population (e.g., Arab troops in another Arab country), and this may serve as a bridge to the rest of the military operation. Nevertheless, additional cultural diversity within the multinational force could complicate relations and coordination among themselves. Diversity within a national force can also affect coordination and cooperation. Recent survey data collected in Somalia by Miller and Moskos (1995) showed that gender, race, and military occupational specialty influenced U.S. soldiers' attitudes toward the conflict and attributions made by them about the plight of the local population. It also affected the choice between adopting a humanitarian or a warrior strategy in dealing with the local population.

Perceptions of Conflict

Another impact of culture is the differential perception of conflict. In most operations other than wars, conflict is likely to exist, and the interacting parties may view it quite differently than does the soldier. Also, across cultures, parties tend to perceive the conflict quite differently (Lederach, 1995). People from many nonindustrialized cultures think of conflict as the normal way of interacting. From childhood, they are taught to settle differences by fighting (Merry, 1989). They tend to accept and even rely on conflict for their social interactions—that is, conflict has a "win-win" appeal. In most Western cultures (i.e., the soldier's culture), conflict is often viewed as one person's opposing or negatively affecting another person's interests (Donohue and Kolt, 1992; Pruitt and Rubin, 1986; Putnam and Poole, 1987; Thomas, 1992)—that is, conflict is perceived as having a "win-lose" effect on the parties.

From a different perspective, Polynesians and several other agriculture-based societies view conflict as a mutual entanglement that is detrimental to both parties (Wall and Callister, 1995)—that is, the situation is "lose-lose." For Koreans and residents of other Asian countries with a strong Confucian underpinning, conflict is viewed as a mutual disruption of society's harmony (Augsburger, 1992; Hahn, 1986). These societies feel that the character and impact of conflict on the disputants is irrelevant, although it is "lose-lose." The major negative impact is the disruption of the larger community and the violation of its norms.

On one hand, the implications of these culturally differentiated perceptions are to some extent rather general and clear-cut. For example, the soldier needs to be informed about how the parties where he or she is

posted view conflict and how they are apt to react to his or her mission. Such knowledge, passed along in training, will provide a better operational background for making strategic and tactical decisions in the culture. In many cases, on the other hand, the implications are culture-specific. Consider these examples. In a nonindustrialized society that views conflict as a normal way of interacting, the soldier's attempts to resolve the conflict or control the relationship between the parties will probably fail, because conflict has utility for both sides. Here the soldier can probably be successful in improving his relationship with each side; likewise, he can probably successfully contain the conflict or reduce the negative impact on third parties.

In a Western culture, the soldier can improve the relationship between the parties by pointing out the integrative potential in their positions. Simultaneously, trades can be worked out in which one side loses on one issue but wins on another.

For a society that views conflict as mutual entanglement, the soldier can intervene forcefully, as do mediators in their society (Wall and Callister, 1995). The soldier can forcefully and acceptably point out who is wrong, call for apologies, ask the other side to forgive the offending party, and formalize the disentanglement agreement.

For cultures that view conflict as a disruption of the harmonious status quo, the forceful, hands-on approach will probably not be accepted. Seldom is mediation carried out that way in their society, and whenever it is implemented, the mediation is never undertaken by an outsider (Kim et al., 1993). The soldier, when posted to these cultures, must know to present him- or herself as a resource to the society, which will resolve the disharmony. For example, instead of putting the disputants together, the soldier might offer to transport senior members of the society to the dispute location.

Societal Structure

A fourth cultural factor of concern is the society's structure. Many societies are structured along family, extended-family, and clan lines. Consequently, when conflicts arise between persons, families or clans, these societies traditionally turn to mediation or negotiation by elder members or to ritualistic confrontations for settling the dispute. Given this tradition, the soldier must understand he or she is going to be perceived as an outsider and, when acting as a third party, as an unwanted intervener. In such a culture, the soldier will find it difficult to obtain an agreement between the conflicting parties, let alone one that is fair (by Western standards) or one that maximizes the joint benefits for the parties. In this situation, the standing community powers will determine the agreements and appropriate payoffs.

Norms

As implied above, family/clan structure often brings with it the norm that relationships (including conflicts) among members will be handled within the family or clan. A second norm—of unknown origin—is that of reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960). In Western societies (Homans, 1961) and in Japan (Goldman, 1994), people feel that an outcome given to one individual or group obligates that person, in return, to give an outcome (repayment) in some form to the other person. Similarly, a cost imposed on a person permits, even obligates, him or her to retaliate against the person imposing that cost. Although many cultures abide by this norm, others do not. Rather, they perceive that an outcome given by one party to another is a sign of weakness or deference. Thereby, it does not obligate the recipient to reciprocate; instead, it raises the expectation that the original party should deliver an additional outcome.

Because the reciprocity norm has a strong impact on an individual's behaviors, the soldier needs to know if that norm exists in the culture to which he or she is posted. For example, in cultures with strong hierarchial levels, reciprocity is not a societal norm. There will be some reciprocity within levels, but not between them. Typically, the higher-level person does not initially make a concession to a lower-level person, because that would be incongruous with his or her status. And when receiving a concession from a lower-level person, the higher-level person does not reciprocate, because he or she considers it a gift to which a high-level person is entitled (Augsburger, 1992).

As for the lower-status person (in a high-low status relationship), he or she seldom receives a concession (either initially or reciprocally); one is therefore not expected, nor is reciprocity. In this setting, the soldier will typically not be perceived as having equal status. Consequently, the parties he or she is dealing with will not behave reciprocally toward him or her. Therefore, the soldier as a primary party should not adopt a reciprocity strategy or make undue investments in integrative bargaining tactics when the opponents do not hold to the reciprocity norm. These would probably yield limited benefits.

In addition, the third party should not rely on reciprocity for moving the opponents off their positions and nudging each toward the other. Rather, in the nonreciprocity culture, the soldier should build his or her own strength and rely more on hard force to move the parties.

In sum, soldiers may have to deal with many subcultures in a given operation and thereby use different—seemingly incompatible—tactics. In such situations, the soldier must be observant, responsive, adaptive, and tolerant of his or her own inconsistency. For example, when posted to a developing country, a soldier may find him- or herself negotiating with a

group containing a local soldier (who is accustomed to taking orders), an uneducated bandit leader (who handles social relations through conflict), a tribal leader (who expects to be treated as a leader), and a dozen confused, displaced peasants. In such a situation, the soldier might negotiate differently with each party or subgroup. Or he or she might force the group to choose a leader and then negotiate with that leader.

Training

It is evident that soldiers in many operations will have to be aware of cultural differences and trained to deal with them. One approach is elicitive training, in which culture is viewed not simply as an influence on conflict but rather as the essence of the approach. Conflict management is defined through cultural experience, values, and assumptions. The approach contrasts with the idea that techniques can be used in virtually any setting or that they can be adapted to particular settings.

Key features of the elicitive approach to training are elucidated by Lederach (1995):

- Training is intended to build relationships rather than to teach specific skills. Trainees are considered to be resourceful people capable of discovering or creating models of intervention rooted in their own context.

- Training is intended to identify and then coordinate the resources that exist in communities. Rather than transferring concepts and methods used in other settings or teaching everyone to use a common model, the concepts are developed anew within the cultural community.

- The training process moves away from emphasizing trainer expertise and toward emphasizing participant discovery. The interaction process rather than the techniques used is critical.

- Trainer expertise is used together with participants' concepts and methods, taking into account its own cultural origins and biases. The trainer needs to recognize the cultural assumptions implicit in any model and identify explicitly the differences that exist between his or her own and the participants' approaches.