2

Implications of Population Change

Introduction

Major changes in the demographic profile of the United States are under way, and these changes are projected to accelerate in the next several decades. Important demographic shifts include the aging of the population and the projected growth of the oldest old (those 85 years of age or more); the changing racial and ethnic composition of the population resulting from immigration and the rapid growth rates of the minority populations, especially those of Hispanic and Asian origin; the shifts in family patterns (particularly the trend toward smaller family size, childlessness, and divorce); and increasing poverty.

The growing elderly population will be a major determining force in the next century for the demand and supply of health services and, therefore, for the type of resources needed to provide those services. The implications for, and challenge of, the increasing number of aged in the years ahead are compounded when the projected racial and ethnic composition of the population is taken into account along with the age distribution of the elderly population.

These shifts take on added importance and urgency in the context of a rapidly changing health care system, placing intense stress on the system as it tries to hold down expenditures and, at the same time, increase access and maintain quality of health care.

Changes in population imply changes in the health care services that will be needed in the years ahead, especially among the elderly population. The growth and diversity of the elderly population, and a sociodemographic profile of the elderly population are described in the following brief overview. The chapter

touches on the health status of, and use of health services by, this segment of the population. It concludes with a brief discussion of the implications for society in meeting these needs for health care services in the next century. The main purpose of this chapter is to provide a general perspective for understanding the implications of these population changes on the demands for health care services in hospitals and nursing homes and the supply of an adequate nursing workforce to provide these services.

Growth Of The Population

The population of the United States has increased by 12 million people, or 5.1 percent, since the 1990 census. Recent projections issued by the Bureau of the Census indicate that the population is expected to reach 276 million by the year 2000, and 392 million in 2050, amounting to a more than 50 percent increase since 1990 (Bureau of the Census, 1993a). The high level of immigration is a major factor contributing to the projected growth of the U.S. population.

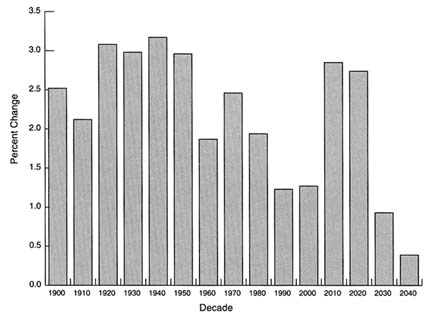

The U.S. population is aging and the population in the 21st century will be older than it is now. The growth of the older population may be considered as one of the most important developments of the twentieth century. In 1900, there were 3.1 million people 65 years of age and older, or 1 in 25 persons. In 1994 this number was around 33 million or 1 in 8 persons (Bureau of the Census, 1995b). Yet the growth to date is just the beginning of the aging of America. In fact, the population 65 years of age and older is growing more slowly between 1990 and 2010 than at any time in a period of nearly 130 years. This reflects the aging of the low fertility generations of the 1920s and 1930s (see Figure 2.1). The elderly population, however, is projected to continue to increase both in numbers and as a proportion of the total population. It is projected to more than double by the middle of the next century, increasing from nearly 34 million, or 13 percent of the total population, to 80 million in 2050, or nearly 20 percent of the population. Most of the increase is expected to occur between 2010 and 2030, when the ''baby-boom" generation enters the elderly years (see Figure 2.1).

While this rate of growth is projected to drop after 2030, there will continue to be a large proportion of elderly persons in the population. About 40 to 50 years from now it is likely that there will be more elderly persons than young persons (under 15 years of age) in the United States. These projections take on added importance when the age distribution and the racial and ethnic composition of the projected elderly population are considered.

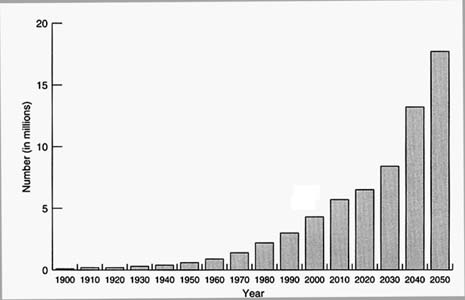

The elderly population is growing older. The population aged 85 and older is the fastest growing age group in the U.S., and it is projected to be nearly six times as large by 2050 as this age group was in 1990 (see Figure 2.2). It is also the most rapidly growing age group among the elderly population. Fewer children and increasing life expectancy have contributed to this shift in the population composition. A 65-year-old person can expect to live another 17 years, and

FIGURE 2.1 Average annual percent change in population 65 years and older, United States, 1900–2040 (middle series projections).

SOURCE: Bureau of the Census, 1993a.

FIGURE 2.2 Number of people 85 years and older, United States, 1900–2050 (middle series projections). SOURCE: Bureau of the Census, 1993c.

those who live to age 85 have an average of 6 more years of life remaining (NCHS, 1993b). This rapid growth of the oldest-old population will have a major effect on the health care system in terms of services needed, education, training and experience of health personnel, knowledge of diseases and treatments for the aged, and demands on resources for the services used by this segment of the population.

Diversity Of The Population

We speak of "the elderly" as if they were a homogeneous group. Like the rest of the population in the country, they vary widely in terms of their racial composition, ethnic origin, socioeconomic circumstances, family composition, living arrangements, and health care needs.

Racial and Ethnic Composition

An important factor with major implications for the future course of the nation's elderly is the changing racial and ethnic composition of the U.S. population. Since 1980, the growth of minority populations as a whole has been substantially greater than that of the white population. As a result, each of the minority racial and ethnic groups increased during the 1980s as a proportion of the total population, while the non-Hispanic white population declined as a proportion of the total population. Under current assumptions, this trend is projected to accelerate in the years to come, leading to increasing racial and ethnic diversity of the population: by the year 2050, the non-Hispanic white population will account for a little more than half of the nation's people (53 percent). The Hispanic population will experience the largest increase, reaching 21 percent of the total population by 2050. The black population is projected to double its present size by the middle of the next century. Although starting from a much smaller base, and therefore adding fewer people, the Asian and Pacific Islander population is projected to be the fastest growing racial group, with annual growth rates that may exceed 4 percent during the 1990s.1 By 2050, this population group is projected to be five times its current size (Bureau of the Census, 1993a).

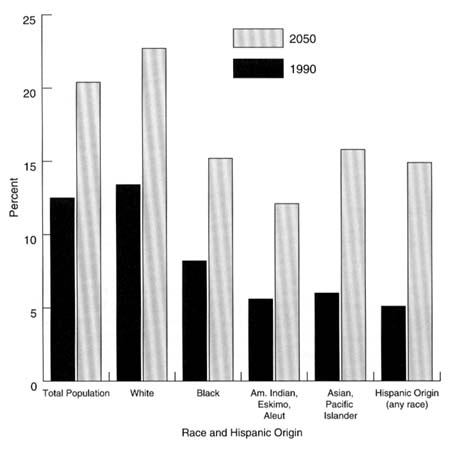

As with the total population, the elderly population today is predominantly white, but more racial and ethnic diversity can be expected in the years ahead (see

FIGURE 2.3 Percent of population 65 years and older by race and hispanic origin, United States, 1900 and 2050. SOURCE: Bureau of the Census, 1993c.

Figure 2.3). The Hispanic population is projected to account for an increasingly larger proportion of the elderly population as the large numbers of current immigrants begin to age. In 1994, 1 in 10 elderly were of a race other than white. By 2050, this proportion is expected to rise to 2 in 10. The share of the elderly who are of Hispanic or Asian origin is expected to increase rapidly in the coming decades (Bureau of the Census and the National Institute on Aging, 1993b).

In general, minority groups reach old age with fewer economic resources, and they tend to have less education than do non-Hispanic whites. They may also have distinctive health needs, and some—especially immigrant minorities—may follow the diets, health practices, and beliefs of their cultures, which may not always be well understood by some care givers. Thus, as the ranks of the elderly

minorities grow, their needs, values, and preferences may necessitate fundamental changes in programs and services for the health care of the elderly.

Access to health care is a function of socioeconomic status, but also to some extent, level of acculturation, ranging from family structure, to education, and facility with the language. Such sociocultural barriers could arise because of differences between receivers and givers of care related to health beliefs and behavior or knowledge about medical services. These differences could make patients reluctant to seek care or comply with prescribed treatments, make care givers insensitive to the needs of patients, and strain relationships between the institutions and their communities.

These barriers often are compounded by inadequate command of the English language. Many elderly immigrants speak little or no English. In 1990, 1 in 7 Americans—nearly 32 million people—spoke a language other than English at home, up from 23 million in 1980. Although fluency in multiple languages is an advantage, speaking a language other than English at home is often a marker for families that are not fluent in English. Among those who speak a language other than English at home, 2 persons in 10 either have very limited English skills or do not speak the language at all. Nearly 1 million persons live in "linguistic isolation," that is, in households where no one aged 14 or older spoke English at all (Bureau of the Census, 1990). The implications of these trends are immense for providing culturally sensitive care and interaction between patients and providers at all levels, and for planning the supply and distribution of nursing personnel.

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Gender Distribution

More women survive to old age than men. In 1994, elderly women outnumbered elderly men by a ratio of 3 to 2, and this difference increases markedly with advancing age. After age 75, most elderly men are married and living with their spouse. Women are more than three times as likely as men to be widowed and living alone. Thus, most elderly men have a spouse for assistance when health fails. The likelihood of living alone increases with age, but much more so for women (Bureau of the Census, 1995b).

Living Arrangements

Changing patterns of family formation and composition (late marriages, smaller families, divorce, childlessness) mean that whereas today's elderly generally have children to turn to when in need, the elderly baby-boomer generation will have far fewer family resources, and specifically fewer younger persons to take care of them. As more persons live longer, issues surrounding the care of the elderly will become more prevalent. Increasingly, those who may be consid-

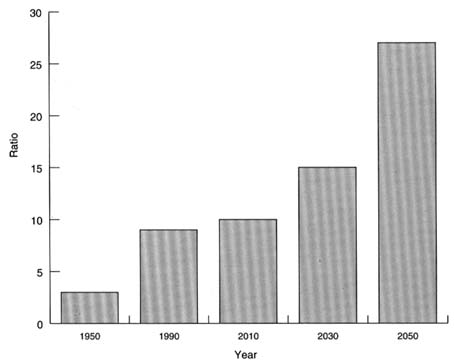

FIGURE 2.4 Parent support ratio, United States, 1950–2050 (number of people 85 years and older per 100 persons 50–64 years old, middle series projections).

SOURCE: Bureau of the Census, 1993c.

ered the "young old" (i.e., those in their 50s and 60s) will have surviving older parents and other relatives and may be faced with the prospect and expense of caring for them. According to the Bureau of the Census, the parent support ratio (defined as the number of persons aged 85 and over per 100 persons aged 50 to 64) has tripled from 3 in 1950 to 9 in 1990; this ratio is expected to triple again by the middle of the next century, increasing to 27 (Bureau of the Census, 1993c; Bureau of the Census and the National Institute on Aging, 1993a). (See Figure 2.4.)

The 50- to 65-year age group is often referred to as the "sandwich generation" since they have responsibilities of caring for their children and at the same time of caring for their very old family members. The problem of parent care affects working-age members of the family, especially women who historically have been the informal care givers in the family. With increasing numbers of women in the labor force, the demand for more formal care giver arrangements is increasing.

Income and Poverty

Today's elderly on the average are economically better off and in better health than their counterparts of a few decades ago. Despite the overall improved economic condition of the elderly, significant income differences are observed among various subgroups. In general, minorities, women, the very old, and those who are living alone are all vulnerable to low income and consequent poverty. About 12 percent of the elderly population is poor; the rates are 33 percent for older black persons and 22 percent for elderly Hispanic persons. Elderly women have a higher poverty rate (16 percent) than men (9 percent). Many more of the elderly population are concentrated just above the poverty threshold (Bureau of the Census, 1993b, 1995b).

Living alone is a significant indicator of the likelihood of an elderly person being poor. In 1991, about 18 percent of elderly men and 27 percent of elderly women living alone were poor. As in other characteristics of the elderly population, there were differences among the major racial and Hispanic-origin groups. Nearly 24 percent of elderly white women living alone were poor. One-half of the elderly women of Hispanic origin living alone and 58 percent of the black women living alone were poor (Bureau of the Census and the National Institute on Aging, 1993a).

Social Security and Medicare have contributed in a large way to improve the economic well-being of the elderly. However, Medicare pays for short stays in nursing homes after hospitalization, but does not cover long-term care. Much of the cost of long-term care is borne by the elderly and their families and only when their resources are depleted does Medicaid cover costs. The elderly persons' need for long-term care, at home or in an institution, for example, and the large role played by government programs, make the elderly population economically vulnerable (Treas, 1995a,b).

Health Status And Disabling Conditions

Today's elderly persons are in better health than their counterparts of some years back. The age-specific rates of disability have begun to decline, particularly among the very old (Manton et al., 1993). Women 85 years of age can expect to live free of disability for two-thirds of their remaining life (Suzman et al., 1992). At the same time, frailty is very common at an advanced age owing to disease, the aging process, disuse of muscles, neglect, or depression.

Although the overall health of elderly persons has improved, many are dependent and frail, with one or more chronic conditions. The risks of chronic conditions and functional impairments increase with age. Most elderly persons report at least one chronic condition such as arthritis, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, hearing impairments, osteoporosis, and senile dementia. Some of these conditions may be life threatening; others affect the quality of life.

The risk of chronic and disabling conditions increases with age. As more of the elderly live to the oldest ages, increasing numbers will face chronic, limiting illnesses or conditions. The prevalence of these major chronic conditions among the elderly is five times that observed in younger persons. These conditions result in dependence on others for assistance in performing the activities of daily living (ADL), especially among the older elderly, portending a significant increase in the need for health care and social support services.

A person's health declines in older ages because of age-related chronic conditions and disabilities. The proportion of persons needing assistance in everyday activities increases with age. These facts suggest that a large number of elderly will seek hospitalization for serious acute and chronic conditions and they will seek long-term care as part of a continuum of care from independent living to assisted living to institutional care.

Alzheimer's disease is the leading cause of dementia in old age. The risk of the disease rises sharply with advancing age, from less than 4 percent of noninstitutionalized persons 65 to 74 years old to nearly half of those 85 years and older. It afflicted an estimated 3.8 million noninstitutionalized elderly in 1990 (Evans et al., 1990). It is a major reason for older persons' being institutionalized. If no breakthrough occurs in prevention or cure, the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease will increase substantially in the years ahead as the oldest age groups in the elderly population increase. In 2050, the number of persons 65 and older affected by Alzheimer's disease is estimated to be around 7.5 million. Increases in the oldest age groups will account for most of the projected increases over this period if no treatment has been found (Evans et al., 1990). The number in the 65- to 74-year age group is expected to rise only moderately. In contrast, the number affected by this disease in the age group 85 and older will increase almost sevenfold by 2050. These numbers indicate the magnitude of the problem, today and in the future.

Use of Health Services

The aging of the population affects the demand for all health care services, including hospitals, and long-term care. Older persons use more health services than their younger counterparts because they have more health problems. They are also hospitalized more often and have longer lengths of stay than younger persons. The growth of the elderly population is likely to result in increases in inpatient admissions. (Some signs of that happening are reflected in recent statistics as discussed in Chapter 3.)

Thus, hospitals will have to increase their sensitivity and ability to care for the acutely ill aging population. An increase in the number of elderly patients requiring more assistance in all aspects of their care, including ADLs, will impact on staffing requirements for nursing services in hospitals. Moreover, as the length of stay in hospitals declines in general, the emphasis on discharge planning

becomes greater than ever. With a shorter length of stay, clinicians have less opportunity to prepare the patient and family for care at home. This becomes more complicated with the aging patient who often exhibits functional decline requiring more intense teaching in preparation for discharge and care at home. The problem is compounded by language barriers.

As the population ages and develops chronic illnesses, the demand for long-term care services including nursing home services will increase. The number of dependent elders (especially those over age 75) is expected to grow as the proportion of total elderly in the population increases (Griffin et al., 1989; Strumpf and Knibbe, 1990). Dependence for assistance ranges from instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), such as cooking, shopping, and cleaning, to personal care ADLs, such as toileting, dressing, bathing, transfer and ambulation, and eating.

With increasing age and disabilities of the residents, shortened hospital stays, and early discharges from hospitals, the demand for nursing facilities to provide more complex services is growing (AHCA, 1995). The degree of medical instability, impairment, and severity of illness in nursing home residents is increasing (Hing, 1989; Shaughnessy et al., 1990; Kanda and Mezey, 1991; Schultz et al., 1994). Medical technology, such as the use of intravenous feedings and therapy, suctioning, rehabilitative services, respiratory care, ventilators, oxygen, special prosthetic equipment and devices, formerly used only in the hospital, has been extended to nursing facilities. These services require more professional nursing care, judgment, supervision, evaluation, and resources than in the past (Shaughnessy et al., 1990).

Only about 5 percent of elderly persons live in nursing homes. However, the total number of elderly persons living in nursing homes has increased in a manner consistent with the increase in the elderly population. Nursing home use increases with advancing age. Whereas 1 percent of those 65 to 74 years lived in a nursing home in 1990, nearly 1 in 4 aged 85 or older did (Schneider and Guralnik, 1990; Bureau of the Census and the National Institute on Aging, 1993a). If current use patterns continue, more than one-half of the women and about one-third of the men who turned 65 years of age in 1990 can be expected to enter a nursing home at least once in their lifetime (Murtaugh et al., 1990). About 43 percent of persons who were 65 years old in 1990 are projected to enter a nursing home some time before they die; more than half of them will spend at least 1 year of their life in a nursing home, and about 21 percent will spend at least 5 years there (Kemper and Murtaugh, 1991). This proportion increases with age. The growth of alternative long-term care settings appears to be having some impact on reducing the demand for nursing home care. Nevertheless, the need and demand for nursing home care is expected to continue. With the growing elderly population and the concomitant increase in the number of persons with multiple chronic conditions and disabilities, these facts have major implications for both medical and nursing practice and for the financing of long-term care.

Conclusion

The projected changes in the composition of the U.S. population and the growth of the elderly, especially the older elderly, pose a serious challenge for public policies as they relate to the health and social well-being of that segment of the population. Because a person's risk of being institutionalized is unpredictable and the potential economic consequences are devastating, protecting older Americans from the costs of nursing home care is an important and much debated policy issue. The aged population also will be a major force to be contended with in shaping the health care delivery and financing systems that promote high quality of care, and in developing a nursing and other health care workforce that is knowledgeable and sensitive to the special problems and concerns of the diverse elderly population. While planning today in an environment of budget cuts and cost pressures at all levels, innovative and creative ways must be developed and tried to ensure access and equity in meeting the increasing demands of tomorrow for health care services that will result from these shifts.

The challenge of planning for an aging society will be to recognize and address the differences that already exist within today's generation of elders, as well as those likely to shape the needs of future generations. "The unprecedented increase in the number of older people and the rapidity of the growth in their share of the total population is a new social phenomenon offering both problems and opportunities" (Soldo and Agree, 1988, p. 42).