4

THE MENTOR AS SKILLS CONSULTANT

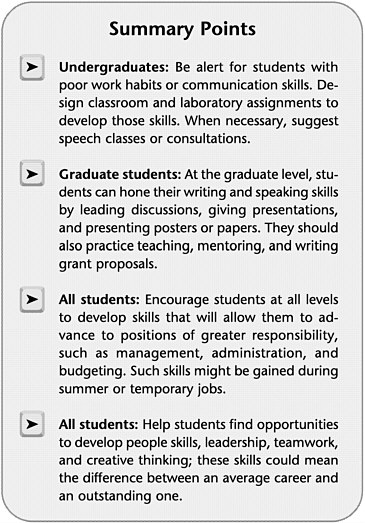

Students must augment their field-specific knowledge and experience with a variety of other skills if they are to make the best use of their talents. Beyond learning to communicate about science, many students need to develop informal communication skills in general, such as the ability to express themselves clearly and understand others' responses. You can help them develop these other skills in the context of many learning activities.

Developing Skills as an Undergraduate

Planning and organization. Many undergraduates have little experience in organizing tasks and making good use of time. You can help them acquire this skill, beginning with simple scheduling. Use mentoring appointments as a framework.

Writing ability. Clear writing is essential to most careers, especially those in administration and management. Engage your students in writing tasks and emphasize its

importance. Your institution might offer writing programs; if so, be sure that they address the special needs and contexts of technical writing. If they don't, lobby for such a program-or start one yourself. There are many resources that can help you do this.

Oral communication. Speaking is at least as important as writing. Students must be able to present ideas and results to other scientists and engineers, as well as to the lay public and specialists in other fields. For students with low confidence, begin with "safe" exercises: Ask them questions and let them respond without interrupting. As they gain confidence, move on to class presentations and talks at student disciplinary-society meetings. Help them develop their research presentations. Videotaping practice sessions can enable students to see correctable habits, and it helps build their confidence. Watching oneself on videotape is often embarrassing; let students watch the tapes in privacy. Many students benefit from professional training, via speech classes or consultation.

Teaching. One of the most important communication skills is teaching, a skill that undergraduates can begin to develop. One way is to accompany them to high schools where the students can offer career guidance and college information. The undergraduate gains a stronger connection with you and becomes an "expert" to the high-school students.

Developing Skills as a Graduate Student

Communication skills. Rather than withdraw into the isolation of research, students should continue to develop their writing ability and oral expression during graduate

years. If they are teaching assistants, they might learn more from leading class discussions than simply grading papers. Use laboratory and other meetings, journal clubs, and department seminars as opportunities for presentations, brainstorming, and group critiques. Eventually they should present posters or papers at national society meetings.

Teaching. Graduate students should have regular practice in communicating their ideas. Universities, industries, and other employers place great importance on instructional skill and the ability to communicate ideas. Graduate students can work with their teaching center, give laboratory seminars, and teach or tutor undergraduates. A senior student can gain excellent experience in mentoring a junior student in a laboratory context, taking some responsibility for the student's progress. Encourage them to design teaching material of their own. Attend teaching events and offer feedback.

Grant proposals. Practice in writing grant proposals, like teaching, must begin early. Suggest practical exercises, such as applying for funds to attend a professional meeting or perform an independent research project. As students gain experience, they will be able to provide productive help with your own proposals.

Skills for All Levels

Nonacademic abilities. Most jobs require skills that do not appear in the core curriculum. These skills-such as administration, management, planning, and budgeting-can sometimes be developed through elective courses, temporary jobs, or off-campus internships. Students can benefit from multiple credentials (i.e., a second degree, nonmajor courses, or nonacademic skills) when preparing for a career.

|

A Nurse Who Became a Research Manager

She completed her BS cum laude, entered graduate school at the University of Rochester, and in 4.5 years had a master's and a PhD in chemical physics. She was hired as a research scientist by Eastman Kodak Company, where she is a senior research scientist who also supervises technology-development projects. "In grad school I knew I wanted to do research, and I thought I would become a professor and help my community back home in California. But my adviser told me it was too difficult for women to get grants or academic jobs. I didn't have the experience to know there were grants for minorities, and my adviser didn't know it. Fortunately I've had a wonderful research experience here. And Kodak, being a big company, has been able to support some of my other goals." Dr. Garcia-Prichard has worked hard to reform science policy and education, serving on the Clinton-Gore transition team, the National Science Foundation Education and Human Resources Directorate, an American |

|

Chemical Society editorial board, and the board of a local community college. "I want students today to be better informed than I was about careers. For example, they need to know what kinds of grants there are and who can get them. Also, there's a huge gap between what students learn in universities and what's needed in an industrial workplace. Here I work in physical chemistry, but I also have to be able to collaborate with materials scientists, engineers, and chemists. "And they should know that the corporate environment is changing today. Shareholders are forcing corporations to downsize staff, but the work still has to get done. "Choosing the right adviser can help-someone who not only is a good scientist, but is savvy about careers and understands what you need. If you pick a famous scientist who is not a good caregiver, you end up staying in school too long and doing a lot of their work. I was done in 4.5 years, and part of the reason was that I stood up to my adviser. I told him, if you want someone to do your laboratory work, you'll have to find someone else. I'm here for a chemistry degree, not a degree in plumbing." Of course, that bold approach will not always be successful. The best advice for students in dealing with their advisers is to be honest, persistent, and communicative. Because the student's goals are not usually the same as those of an adviser, a good relationship requires continued effort, good judgment, and good will—on both sides. |

People skills. Discourage students from working in isolation from others. People skills-the abilities to listen, to share ideas, and to express oneself-are indispensable for most positions. Look for opportunities to include shy or withdrawn students in social gatherings and group projects. Excessive shyness could be a symptom of more-serious personal problems, for which you might want to suggest counseling.

Leadership. Advise students to join and take a leadership role in disciplinary societies, journal clubs, student government, class exercises, and volunteer activities.

Teamwork. Learning is often most effective within a community of scholars. Cooperative problem-solving skills can be developed through group exercises, collaborative laboratory work, and other team projects. Team skills have gained importance with the trend toward multidisciplinary work in science and engineering.

Creative thinking. A productive scientist or engineer is one who approaches problems with an open mind. Give students permission to move beyond timid or conventional solutions and remind them that original thinking carries some risk. Provide an environment where it is safe to take intellectual risks.

For a list of personal skills and attributes that are helpful to scientists and engineers, see appendix B in COSEPUP's Careers in Science and Engineering: A Student Planning Guide to Grad School and Beyond.

As a single mother of two, Diana Garcia-Prichard worked as a nurse to support her family. But when she signed up for chemistry courses at California State University at Hayward, she felt her life shift. "Physical science was perfectly suited to my thought processes," she says. "It was the first time in my life that I found something I really wanted to do."

As a single mother of two, Diana Garcia-Prichard worked as a nurse to support her family. But when she signed up for chemistry courses at California State University at Hayward, she felt her life shift. "Physical science was perfectly suited to my thought processes," she says. "It was the first time in my life that I found something I really wanted to do."