9

Technology

Technology is playing an increasingly critical role in the success or failure of SMEs. Computerized machines are replacing manual machine tools, CAD is replacing manual drafting, and computers are being used to track inventories, even in small shops. Although up-to-date manufacturing and process technologies are critical, they are no longer the only required technologies. Information technology has become one of the keys to operating success. Internet technologies alone are changing the mechanisms of communication, marketing, selling, buying, and generating revenue.

Suppliers are finding that one of the few escapes from the relentless pressure to reduce prices lies in change and innovation. The addition of value through innovative product and process design can sometimes differentiate the output of an SME from its competitors enough to enable profitable operation even in areas with high labor costs, such as the United States.

Successful companies distinguish themselves from their competitors by anticipating opportunities, selecting appropriate technologies, and using them for competitive advantage. Many SMEs, however, find gaps between customer supply chain requirements and their technological capabilities. The following sections offer suggestions for addressing some of these gaps.

ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATIONS, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY, AND E-BUSINESS

The advent of the Internet and e-business is increasing competition

by facilitating comparison shopping, raising customer expectations, providing ready availability of customized products with expanded features, and reducing costs. The Internet is a powerful and effective integration tool that can enable substantial improvements across the supply chain. It offers SMEs, in their roles as suppliers, manufacturers, and customers, a huge potential for exchanging information easily and securely with other supply chain participants. According to J. Cohen, the Internet can save supply chain participants from 18 percent to 45 percent in logistics costs through quicker order placement, faster delivery of goods, fewer transaction errors, and more accurate pricing (Cohen, 1999). The Internet can also be used to help manage inventory by providing a framework for just-in-time manufacturing. Inventory reductions during the past 10 years were enabled primarily by expensive electronic data interchange systems that linked inventory databases. Only wealthy companies could afford these systems. Now, versatile applications of the Web are providing similar opportunities for SMEs at substantially lower costs. The Internet can also be useful for removing traditional geographic barriers to collaboration and integration within the supply chain.

By using the Internet as an integration tool, SMEs can

-

improve reaction to changing demands and markets

-

optimize resources throughout the supply chain

-

more efficiently source lower cost materials

-

achieve shorter lead times and better due-date performance

Communications

Although face-to-face contacts and the use of telephone, fax, and surface mail are still essential, they are no longer sufficient to ensure competitiveness. Effective communication requires additional capabilities, such as e-mail, electronic data transfer, and more. Even small suppliers should consider creating a supporting information infrastructure of appropriate size and complexity to provide information in useful form to the right people at the right time. New communications technologies can provide substantial benefits to members of the supply chain. For example, traditional methods of processing purchase orders are slow and costly. The OEM receives a customer order, enters it into the MRP (materials requirements planning) system, writes its own purchase orders in response to component forecasts from the MRP system, and sends them to suppliers. Upon receiving the orders, suppliers execute the same procedures in their companies, and so on throughout the supply chain. With current electronic communications technology, purchase orders for lower tier parts and services can flow almost instantaneously and at virtually no

cost throughout the supply chain. Although up-front investments for these electronic systems can be significant, they reduce the administrative costs of placing orders and can dramatically improve lead times and responsiveness.

There are many levels of data and communications integration. An SME, commensurate with its resources, should determine the appropriate level. At a minimum, the basic capabilities should include electronic networks based on generally accepted data transmission protocols, such as e-mail and file data transfer on the Internet, and private couriers, such as FedEx. No SME can expect to remain competitive without all of these. The following statistics provide examples of the ubiquity of these technologies (Ferguson, 1999):

-

A billion e-mails were sent in 1998.

-

Worldwide fax transmission minutes increased from 255 billion in 1995 to 395 billion in 1998 and will continue to grow rapidly for the next several years.

-

Faxes account for one-third of phone bills at large corporations.

-

With lower phone rates and better equipment, the average cost of sending a three-page long-distance fax dropped from $1.89 in 1990 to $0.92 in 1999 via stand-alone machine and to $0.30 via PC.

All levels of integration require the use of a common syntax and semantics so that cross-organizational data can be interpreted identically by all participants in the supply chain. Integration at the highest levels may involve object-oriented data modeling, data warehousing, high-level data protocols, and knowledge-based systems to provide almost instantaneous sharing of knowledge. Implementation of these systems requires extensive time and capital, as well as cultural changes associated with the transition from independent tools used by individuals to dependent tools that link people and organizations throughout the chain.

Recommendation. Although the highest levels of communication capabilities can provide incredible competitive power, they are too complex and costly for most small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs). These technologies should be monitored closely, however, because their costs and ease of implementation are improving dramatically. Internet technologies can provide many of these capabilities today at far lower cost, and SMEs should take advantage of these easy-to-use technologies.

Data Collection and Information Management

A research project by the Cambridge Information Network involving more than 270 corporate chief information officers found that 56 percent plan to install an Internet-enabled real-time link from their enterprise resource planning systems to their suppliers. The market for supply chain management hardware, software, and services is expected to increase by 50 percent in 1999 to $3.9 billion (Wreden, 1999). However, with all of the publicity about interconnectivity, it is easy to lose sight of the essentials of data collection and information management. First and foremost, SMEs must decide which data will be collected and how they will be used. The data management system should then be selected using technologies compatible with other supply chain participants. Competitive advantage is not gained simply through faster communication of data but from the skilled use of the knowledge gained from useful and timely data.

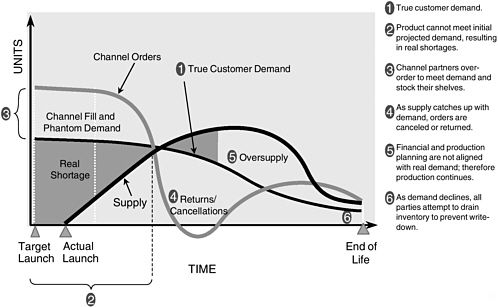

Decision making can be improved through real-time knowledge of sales rates, inventory levels, and production rates throughout the supply chain. These data can be used to reduce oscillations in the system (more closely matching production and inventories to demand) and reduce supply chain misalignment (Figure 9-1). Misalignment occurs when product shipments plus channel fill (the amount of product in the distribution system) are not equal to customer demand. Integration of demand planning, order fulfillment, and capacity planning can enable reduced supply chain inventory levels, improve on-time delivery, and enable more rapid resource deployment to problem areas. By minimizing multiple tiers of report writing and other non-value-added activities, overhead costs and delay times can be greatly reduced.

Collaborative demand planning based on shared customer (order and point of sale) and operational (inventory and availability) data can provide real-time forecasts of demand for all of the partners. If everyone in the supply chain has an immediate and accurate view of demand, the response of the chain, as a whole, can be rapid and synchronized. Distorted or delayed demand forecasts can cause inventory imbalances, delays, and higher costs. Accurate predictions require that SMEs have accurate and systematic methods of generating and sharing demand and supply information.

Several problems with information technology can hinder integration and planning. Information from various functions may be handled by multiple (and sometimes incompatible) electronic systems. Most organizations continually upgrade and migrate their software making it difficult to unite applications in the integration process. Information and

functions are often scattered across the enterprise. Customer orders may be received through a sales force, while finished goods, inventory levels, purchase orders, manufacturing orders, and bills of material may be processed by multiple enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems. Hence, providing information in a timely manner throughout the supply chain can be difficult.

Fundamental decisions based on incomplete information may be less than optimal or even incorrect. Additional materials may have to be purchased at last-minute premium rates, incorrect bills of material may be created, erratic inventory levels may lead to stockpiling and production errors, and delivery dates may be missed. These consequences can have a negative effect on the profitability of all participants and place them at competitive risk. To avoid these problems, many companies are buying expensive enterprise integration software.

The objectives of ERP should include more than enterprise-wide interoperability and consistency. They should also include standardization of functional modules, enhanced reliability, and less need for customization. These objectives are not always achieved, however. Many implementations of ERP require a high degree of customization and extensive changes in business processes. Full implementations in large corporations can take years, and sometimes are not completed or are abandoned entirely.

SMEs may want to defer acquiring even MRP systems. These decisions should be based on assessments that include more than initial system and installation costs. The burden of keeping systems operational, plus the costs of periodic updates, may outweigh system benefits to small manufacturers.

There are many degrees of demand planning integration, ranging from manual sharing of information to integrated reporting of demand and electronic forecasting. As improved supply chain integration software and ERP solutions are introduced, the pressure on participants to embrace technological integration will increase. Implementing supply chain management systems is becoming more difficult because of the rapid growth of ERP systems, which are intended for use by single companies. Supply chains include multiple companies and, therefore, multiple (often incompatible) ERP systems. Thus, SMEs in multiple supply chains are being faced with conflicting demands to use expensive systems that may be incompatible with each other. Communications between incompatible systems can usually be accomplished by use of hypertext markup language (HTML), electronic data interchange (EDI), and extensible markup language (XML), but these bridges tend to be awkward, as well as costly to install and operate. Furthermore, XML tends to be field-specific. Substantial progress has been made in the financial and medical

fields, but little progress has been made to date in manufacturing. Hence, for the foreseeable future, a practical goal for many small, resource-limited suppliers will be to transmit, receive, and handle information in a reasonably timely, effective, and accurate way, generally without the use of complex ERP software.

e-Business

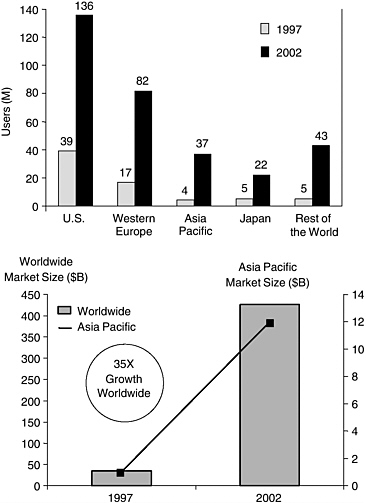

Internet-based technologies deliver ubiquity (universal and high-speed access), economy (cheap, paperless information and transactions), and utility (platform-independent software and services). The growth in Internet usage and business-to-business e-commerce has been dramatic and cannot be ignored. Buyers are still purchasing the same amount of goods, but an increasing portion of these purchases are being made on line. In 1998, businesses spent $43.1 billion on Internet-based purchases from other corporations (Wall Street Journal, July 12, 1999). Forrester Research predicts that by 2003, business-to-business e-commerce will generate $1.3 trillion in revenues, 12 times the estimated consumer market. (Figure 9-2 shows the extent of these worldwide trends.) However, as of mid-1999, only 25 percent of small businesses had Web sites. Concerns about security and underutilization are often cited as reasons for delays in adopting this technology (Grover, 1999).

e-Business technologies can (1) enable direct access to a worldwide, on-line customer base; (2) break down barriers of time and visibility; (3) change the product demand profile; and (4) enable changes in the approach to selling, order taking, and customer service. They can also (1) provide the means for flexible, easy-to-use responses to customer requirements; (2) improve support to product distribution channels, enabling appropriate inventories, improved sales information, and training; (3) provide simplified direct access to supplier products and services; (4) reduce overhead costs for transaction processing; (5) improve access to procurement/financial processes and status; (6) reduce cycle time and cost; and (7) enable the creation of a flexible/agile supply chain with increased synchronization and visibility of inventory.

Although information technologies are transforming many industries, the transition from direct salespeople to e-commerce, for instance, has been slow in coming to SMEs. As of early 1999, more than 90 percent of SMEs with Web sites used them to provide company information, but less than 30 percent used them to sell products and provide on-line customer support. For those who did sell on line, the revenue was a negligible percentage of total revenue (Wall Street Journal, August 17, 1999).

Cost has been one reason for the slow change to e-commerce. Managing an on-line operation can create expensive technical problems and

Figure 9-2 Internet trends. Source: Murphy-Hoye, 1999.

divert management attention that might be better spent on sales or strategy. The creation of e-commerce sites typically cost more and required greater effort than anticipated. Starting a major new e-commerce Web site in 1998 cost an average of $1 million (Wall Street Journal , May 27, 1999). However, SMEs can no longer use cost and lack of computer expertise as excuses for not taking their businesses on line. By late 1999, the cost to set up a small e-commerce Web site had fallen to as low as $100, and the cost for support services per month is about the same. Knowledge of HTML is no longer required. Web site service companies provide templates and instructions in layman's terms, and, for as little as $40 per year, the Web

address and a few words about the company can be inserted into hundreds of Internet search engines and directories.

A typical do-it-yourself process for establishing an SME e-business Web site involves the following steps:

-

First, build a Web site to display products and take orders electronically. Select a Web site service company. Then choose from among predesigned templates. Drag and drop them onto the site, following simple point and click instructions that make the process almost as easy as sending e-mail.

-

Second, contract with a service company to host the Web site. This eliminates the need for acquiring the programming skills and equipment to operate a Web server. The small monthly fee typically includes hosting and basic technical support, as well as the opportunity to create new pages and displays as needed.

-

Third, the SME must advertise and promote the site. The site and its products must be listed or cross-referenced on key search engines where on-line buyers can find them. This is a critical step. SMEs must work closely with the service provider to ensure that the proper links are created to channel targeted customers to the Web site. In addition, the SME must go through conventional sales channels to make sure that existing customers are aware of their on-line presence.

-

Fourth, because most OEMs will only purchase from prequalified suppliers, SMEs must continue to work closely with customers to get their products approved.

A number of services are designed to help SMEs create and operate Web sites. These services include Sitematic Express (sitematic.com), Homepage Creator (ibm-com/hpc), Bigstep.com (bigstep.com), Virtual Office (netopia.com/software/nvo), Yahoo! Store (store.yahoo.com), WebStore (icat.com), and Internet Store (virtualspin.com).

Recommendation. Small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises (SMEs) should keep abreast of customer expectations regarding on-line responsiveness and use e-business service providers to assist them in creating and operating low-cost Web sites for displaying products, accepting orders, and answering frequently asked questions. SMEs without an on-line presence may increasingly find themselves at a strong competitive disadvantage.

Supply Chain Integration Software

Supply chain integration software is an expanded, interactive version of MRP and logistics systems that enables companies to collaborate with suppliers and customers, forecast jointly with greater accuracy, shorten product development and introduction cycles, and reduce inventories. These packages, which are often tailored to specific industries and applications, can include tools for electronic data interchange among supply chain partners and modules that control various functions, such as warehousing, purchasing, inventory control, and transportation. Many systems, even from different industries, have elements in common, including (1) a supplier module incorporating multiple layers of suppliers; (2) an operations module consisting of purchasing, inbound logistics, and manufacturing; (3) a customer module, including distribution of goods and services to multiple customer tiers; and (4) a returns channel for optimizing the handling of defective, warranty, trade-in, and obsolete products.

Using these systems to integrate on a function-by-function basis enables the detailed examination and optimization of results by function across the entire chain. Inventory levels, for example, can be given the visibility required to make coordinated decisions rather than forcing participants to hold redundant inventories to buffer lead times. More extensive integration can achieve greater benefits by optimizing on a wider scale and performing more complex trade-offs. For instance, customer satisfaction can be optimized while balancing service levels, asset utilization, and total supply chain costs. More sophisticated packages integrate and optimize processes across elements of the entire chain. Some contain tools to aid in understanding and coordinating interrelated processes in the overall architecture, including process mapping across successive levels. Modeling and simulation of the supply chain can be performed through features that take advantage of ABC and other productivity analysis tools.

Before purchasing supply chain integration software, companies must decide whether (because of unique requirements, the desire to continue present business practices, or the hope of gaining a competitive advantage) to develop custom modules, often at considerable cost and risk. The alternative is to use a standard software package, which, in many cases, requires that users change business processes to fully utilize its capabilities. Many of the standard packages require further development and are far too complex for most SMEs. Therefore, the highest criteria for SMEs considering purchase of software systems for managing their supply

chains should be ease of installation and ease of use. When SMEs are faced with OEM demands to integrate with their systems, they should carefully analyze the costs and benefits, as well as the strategic implications, including whether their corporate independence would be jeopardized by extensive integration with a single customer.

Recommendation. Despite significant media coverage of the capabilities of business management systems, small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises should evaluate, but generally defer, purchasing enterprise resource planning and supply chain integration software until prices come down, these systems are easier to install and use, and the benefits of specific systems have been more thoroughly validated.

Recommendation. Regardless of the level of integration, senior management in small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises should take the lead in using Internet technologies within their companies. They should closely monitor changes in information technology, invest now in basic capabilities, plan for future investments to support their competitive position, and study how and when to integrate their systems with those of other supply chain participants. Senior management should define data requirements and closely manage the implementation of appropriate data management and electronic communication capabilities.

PRODUCT DESIGN TECHNOLOGIES

The design world is adapting to greatly reduced product cycle times and intensifying time-to-market pressures. Missing a product introduction window in fast-moving industries can completely undermine profitability. CAD, CAM, computer-aided engineering (CAE), design for assembly, design for manufacture, and modeling and simulation systems have significantly reduced the time required for product realization in many industries. Computer-integrated manufacturing (CIM), which enables engineers to take information from CAD systems and use it in a CAM environment, has made it possible to unify all of the basic computer-aided processes involved in manufacturing. With CIM technologies, a single set of product data can be used across a wide spectrum of applications.

Mold designs, welding paths, and computer numerical control (CNC) cutting paths for milling machines and lathes can be generated directly from data derived from solid models created in state-of-the-art CAD applications. With parametric design technologies, the information that shapes the model can be altered easily and quickly. Using these techniques to modify a product design before a commitment is made to

manufacture has significantly reduced the time and costs of retooling manufacturing equipment. Virtual manufacturing pulls all of these technologies together into an agile manufacturing enterprise, a virtual factory on a computer that can analyze and pinpoint flaws in the manufacturing process before they occur on the factory floor.

OEMs in integrated supply chains are increasingly asking suppliers to become more involved in all phases of the product realization process. In a similar manner, SMEs should involve their customers and suppliers in the design process. In many cases, involvement in the design process is a new role for SMEs, offering them opportunities to add substantial value to the capabilities they already provide and linking them more closely with the OEM. Early participation by suppliers can enable better designs for manufacturability, provide better opportunities for implementation of advanced materials and processes, and provide sufficient time for the simplification of tooling. Many SMEs have had to expand their design capabilities to participate. For example, GM recently announced that the new Chevrolet Silverado pickup truck was built without traditional clay or wood models. The truck was designed on workstations with engineering software that enabled vehicle, parts, die, and plant designers to work simultaneously on the new product. Suppliers needed enhanced modeling and simulation capabilities to participate (Manufacturing Engineering, 1999).

Modeling and Simulation

Led by the automotive, aerospace, and defense industries, what began 20 years ago as CAD and CAM has expanded into highly complex modeling and simulation capabilities that use interactive design and development tools to reduce the costs and time required for product development and realization. The U.S. Department of Defense is beginning a major initiative called Simulation-Based Acquisition (SBA), the objective of which is complete modeling and simulation of all major weapons systems prior to manufacturing. Simulation-based design, a segment of SBA, uses a digital knowledge environment to represent physical, mechanical, and operational characteristics of these complex systems. In addition to electronically integrating product and process development, prototypes can be tested in virtual environments prior to fabrication. In response to this initiative, prime contractors are increasingly using these advanced technologies and, to the extent that their supply chains are integrated, they will increasingly expect these capabilities from suppliers. When fully implemented, SBA will go far beyond design, modeling all aspects of the product life cycle, from initial concept through manufacturing, sustainment, and even disposal or recycling.

Indeed, in rapidly changing industries, SBA and other techniques, such as concurrent engineering and simultaneous interactive electronic design and development of products, and processes, will offer more and more advantages.

Design System Limitations

Although high-level integrated computer modeling of electrical, mechanical, and manufacturing processes can reduce product realization costs and although ''best practice" industry leaders use three-dimensional (3-D) modeling, the most common modeling techniques still involve basic two-dimensional (2-D) CAD designs printed on paper (Integrated Manufacturing Technology Roadmapping Project, 1998). This is partly because of inadequacies in current 3-D modeling systems, including difficulties in translating data between applications. Because only some of the "real information" is in the model, communicating the entire model to others who do not use the same system can be difficult. As of 1999, only a few effective tools were available for collaborative, concurrent use by designers and manufacturing engineers, and most of them were technology-specific or product-specific. Although use of national standards, such as the Initial Graphics Exchange Specification (IGES) and international standards, such as the Standard for the Exchange of Product Model Data (STEP) is increasing, their use is complex and expensive, in some cases requiring the assistance of enterprise network administrators.

The Web is not yet ready for collaborative engineering, although 2-D CAD files can be readily converted into standard Internet (pdf) format, which allows them to be inexpensively posted on the Web or sent via e-mail using the Internet. Until lower cost, user-friendly technology is available, this may be the most practical, cost-effective approach for most SMEs. Real-time transfer of large data objects is difficult to accomplish consistently compared to transfers over privately leased lines. Despite advanced technologies, face-to-face engineering meetings with printouts of 2-D CAD drawings can still be the most cost-effective approach to resolving problems for many SMEs. Although effective standard protocols will eventually be developed for 3-D CAD, SME management must use sound judgement in deciding on the timing and extent of implementation of these technologies.

To date, most OEM attempts to use high-performance modeling and simulation packages have been frustrated by limitations in software capabilities and by slow adoption throughout their supply chains. As integrated supply chains migrate toward higher levels of electronic design, modeling and simulation, and rapid prototyping, SMEs will have to

continually reassess their roles. These advanced technologies require substantial investments, and the complexity of leading-edge design tools requires more specialized training and support than many SMEs can afford. The decision can be further complicated because investments in electronic systems to meet the needs of one customer may be of little value in working with another. Furthermore, firewalls must be created so that proprietary information is not transferred between customers. Thus, SMEs should analyze competitors and discuss requirements in depth with customers before making major decisions.

Finding. Advanced electronic systems for product design, modeling, and simulation require further development before they will be practical and cost effective for most small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises.

Recommendation. Small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises should carefully analyze the requirements and opportunities for electronic design systems but defer investing in them, if possible, until system capabilities increase and returns justify the investments.

PROCESS AND MANUFACTURING TECHNOLOGIES

The technology needs of an SME extend beyond electronic communications and design capabilities. SMEs must also remain competitive in materials, processing, fabrication equipment, and all of the other technologies used in their businesses. SMEs in fast-moving, high-technology industries must continually reassess their positions and fill capability gaps. In extreme cases, SMEs in high-technology industries may have to essentially reinvent themselves, their products, and their processes as often as several times per decade. They must focus consistently on the latest technologies, whereas in slower changing or mature industries, the appropriate focus is more likely to be on reliability, cost, and delivery. In most cases this does not mean cutting-edge, or "bleeding" -edge, capabilities; others can pay the price of being the first to debug a new technology. Accepting the risk of trying to be first only makes sense in industries that greatly reward early adopters of new technology. However, implementing carefully selected advanced technical capabilities may be one of the few ways of enhancing profitability in markets with increasing price pressures. For example, a company in the precision forging business may rely on expertise in advanced precision forging techniques to differentiate itself from its competitors.

Competitive advantage can be gained through a combination of

investments, experience, research, experimentation, and operator training. The development of innovative process and manufacturing technologies may offer opportunities for added value, although the costs of such development may be beyond the reach of financially limited SMEs.

Agility, flexibility, and responsiveness are becoming increasingly important in the current climate of rapidly changing customer and supplier needs. Flow manufacturing is a new approach that offers improved speed, response, and flexibility throughout the production, procurement, and order fulfillment process. The basic premise of flow manufacturing is the pull of materials through production and the supply chain based on actual customer demand, rather than the push of materials based on a preset schedule (Blanchard, 1999). Flow manufacturing encompasses many Japanese lean manufacturing techniques, such as reduced cycle times, reduced inventory, mixed-mode manufacturing, and line balancing. The strategy uses a planning horizon of several hours or several days rather than the 12-week horizon of traditional production planning.

Recommendation. Despite the increasing importance and glamour of Internet-based technologies, small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises should not ignore up-to-date manufacturing and process technologies. They remain essential for success.

SOURCES OF TECHNOLOGIES

Technologies for supply chain participation are available from a variety of sources:

-

Many universities are eager to license technologies developed in their laboratories. They are also willing to establish cooperative research and development agreements to develop technologies of interest to their academic staff. Thus, at reasonable cost, SMEs can have access to the same highly skilled people as large OEMs.

-

Government laboratories in the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the U.S. Department of Defense, and the U.S. Department of Energy are under incentive to license, at reasonable rates, non-classified technologies developed with public funds.

-

Modern communications have made it easier to learn about technologies developed in foreign countries. Some of these technologies are excellent and can be licensed. Representatives of the former Soviet Union, for example, are eager to sell or license technologies, especially for Western currencies.

-

Skilled employees and recent graduates can contribute greatly to the development of state-of-the-art technologies. Highly skilled

-

immigrants from economically depressed parts of the world can be hired at competitive rates. International centers, such as Washington, D.C., New York City, and San Francisco, are especially attractive to skilled immigrants, and it may be worthwhile to locate an operation there to access their skills.

-

Acquiring a small start-up company with a key proprietary technology may be less expensive than risking time and money to develop a competing technology.

-

Courses, seminars, conferences, and technical publications can alert and educate employees to state-of-the-art technologies and opportunities for innovation.

-

SMEs in possession of key proprietary technologies have potentially valuable bargaining chips if these technologies are needed by OEMs. The benefits of such a business relationship might include technology cross-licensing, engineering assistance, subsidized manufacturing facilities, and low-cost installation of compatible MRP and electronic design systems.

FINANCIAL ISSUES

Successful participation in many integrated supply chains is becoming increasingly difficult for SMEs unless they have extensive financial resources. Keeping up with new technologies, the increasing demands of supply chain integration, the increasing risks of product liability, and the reserves necessary to respond to rapid changes in the business environment all require strong financial reserves. Substantial investments in capital equipment and training may be required to remain competitive.

OEMs and higher tier suppliers are increasingly demanding that SMEs make specific investments, many of which are not one-time investments. Systems can become technologically obsolete within a few years, and customers may insist on upgrades even sooner. Although 15-year-old production equipment is common, seven-year-old computers are obsolete. SMEs must find ways to meet these demands. Moreover, as OEMs consider establishing long-term relationships with their suppliers, they are evaluating their financial underpinnings and track records more closely. Thus, SMEs must demonstrate a track record of financial stability and implement financial systems to control costs and inventories.

Although financial requirements were not high on the list of SME concerns in the survey conducted for this study, preventing and filling financial gaps is a central issue. To reduce the need for outside funding, SMEs must focus their activities carefully, maximize their cash flow, invest their resources wisely, and take advantage of the techniques of

supply chain integration to reduce the amount of capital tied up in excess inventories and excess manufacturing capacities.

Funding Sources

SMEs must have financial resources in place in advance of need. Establishing sound investor and banking relationships in advance is essential to long-term financial stability, and like all partnerships, these relationships require ongoing attention. Venture capitalists are a potential source of funds, although they are unlikely to fund an SME unless it exhibits an unusual potential for rapid, highly profitable growth.

Large OEMs and supply chain partners sometimes provide resources and "co-investments" for key SME participants, thereby enabling the SME to become a better supplier, strengthening the partnership, and ultimately benefiting the OEM. This strategy has been pursued successfully by Japanese OEMs, such as Canon and Toshiba. OEM investments can take the form of advance payments for products, equity investments, loans, subsidized product and process development, technology transfer, compatible electronic design and MRP systems, training, and access to experienced people. In the past, Ford, for example, often bought conventional machinery for supply chain members if they needed it to produce for Ford. However, as of early 1999, Ford purchases machinery for suppliers only if the machinery is unique for Ford requirements.

Few SMEs have used supply chain management techniques to integrate their own supply chains. These techniques can reduce the need for investing in redundant inventories and excess manufacturing capacities, thereby freeing cash for other investments.

Recommendation. As supply chain integration requirements and the need for new technologies increase the financial requirements imposed on small and medium-sized manufacturing enterprises, they should integrate their own supply chains to reduce redundant inventories and excess manufacturing capacities, thereby freeing cash for other investments.