ideas and information on some key topics for the report. The published literature on reproductive health interventions in developing countries reviewed by panel members and staff largely concerns the epidemiology of particular health problems and field trials of targeted interventions, which are usually carried out within the health sector. The panel chairs decided it would be useful at this meeting to address two relatively neglected sets of issues. One consists of current concerns for programs in both the health and family planning sectors, including the estimation of costs and effectiveness, efforts to improve the quality of services, and service integration. The other set of issues concerns the impacts on reproductive health of efforts carried on largely outside the structure of health services, such as efforts to deal with sexual coercion, education, and mass communication.

Participants in the meeting gave short presentations based on one or more previously prepared papers, summaries of relevant literature prepared for the meeting, or their own work in progress. This report summarizes the background papers and oral presentations, the comments of discussants, and the general discussion at the meeting. For clarity, we have not always followed in this text the order in which points were presented at the meeting, but instead have regrouped material under separate subject headings. This report is necessarily brief, and interested readers are referred to the cited works or to the participants for more information. All participated as individuals, not as representatives of their institutions. The meeting was intended to elicit a wide range of views and provoke discussion, rather than to reach consensus on findings and recommendations, so the participants cannot be assumed to agree with all the statements reported here. The panel is grateful to all those who devoted their time and energy to preparing for, and participating in, this meeting. Their insights and information will help greatly in preparation of the final report of the panel, and should also interest others involved in research and program implementation.

ISSUES FOR HEALTH SERVICES

Cost-Effectiveness of Interventions

The ICPD Programme of Action calls for significant increases in the funding of reproductive health programs. But even if these are realized, the magnitude and severity of reproductive health problems, the large number of apparently worthwhile proposals for new services and improvements in existing programs, and the sheer growth in numbers of women and men of reproductive ages in developing countries will force hard choices among alternative patterns of investment. Cost-effectiveness analysis provides one way to organize the very limited information that exists to help guide the process of choice. This entails estimation of the value of all resources consumed in the production of a service, as well as estimation of the effects produced (in some common metric), for comparison

of various proposed alternative combinations and scale of services. Presentations and discussions at the meeting examined both the promise and the limitations of cost-effectiveness analysis in supporting decisions about interventions to improve reproductive health.

José-Luis Bobadilla presented the methods and some of the results of the analyses of the burden of disease and the costs of services that were prepared for the 1993 World Development Report, Investing in Health (World Bank, 1993). Reproductive health problems were a major contributor to the burden of disease, measured as discounted Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) lost. The DALY measure attempts to combine mortality and morbidity as health outcomes. (See Murray, 1994, for details of calculation.) Some of the reproductive health interventions examined by the World Development Report analysts—family planning, prevention of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and human immuno-deficiency virus (HIV) transmission, antenatal care and safe delivery—are among the most cost-effective investments available to developing countries, and they were included in a package of essential services that the authors of the World Development Report recommended for public financing in low-income countries.1

Family planning proved to be one of the most cost-effective health interventions considered. The World Development Report authors included estimates only for the direct health benefits of family planning for women and children, disregarding the benefits for children's education, women's status, and the household economy, as well as the social costs and benefits of lower fertility rates. A similar point was made about prenatal and delivery care: the cost-effectiveness models used for the World Development Report estimates focus on short-term health consequences and do not take into full account the long-term consequences of low birthweight, so interventions aimed at preventing low birthweight would appear even more cost-effective than others whose benefits were more completely accounted for.

The World Development Report presented results for two prototypical countries, one with low income and one with middle income. The package recommended for middle-income countries would typically involve an expansion of services for the poor, though not necessarily greatly increased health expenditures per capita. The World Bank is now assisting countries to use this framework for analysis with each country's own cost estimates, cause of death and morbidity estimates, and assumptions about the efficacy of services, to produce

|

1 |

The World Development Report was primarily concerned with health services typically provided in developing countries either by the public-sector health services or private practitioners. It did not attempt much analysis of nonhealth interventions like those discussed in the second part of this report. |

more detailed information on types of programs and target coverage and utilization, to tailor the global recommendations to local circumstances.

To illustrate the potential usefulness of calibrating such models with local data, Bobadilla and Peter Cowley presented preliminary estimates of costs and effectiveness of the “mother-baby package” of health services recommended by the World Health Organization, for three countries in which these efforts are under way: Mexico, Ghana, and Tanzania. The costs included amortized capital costs for clinics and vehicles, allocated among health services according to their assumed proportion of patient contacts at the facilities (Cowley and Bobadilla, 1995). For the purposes of the mother-baby package estimates, only clinic-based family planning services were included. Separate data on utilization, contraceptive prevalence, and salaries are used for each country.

The key results from their preliminary estimates are that costs (and cost per DALY saved) can vary widely across countries, even for the same services. Although this is due in part to different estimates of disease prevalence and service utilization, much of the variation is accounted for by differing costs of labor. For example, Bobadilla and Cowley estimated that early treatment of STDs costs more than 10 times in Mexico what it costs in Tanzania (about U.S. $40 per patient per year in Mexico, compared with about U.S. $3 per patient per year in Tanzania), mainly because of differences in salaries. Treatment of an obstetric emergency costs over five times in Mexico what it would in Tanzania (nearly $600 per patient in the former, compared with around $100 in the latter). In Tanzania, which has very high rates of STD prevalence and of HIV transmission, as well as high rates of maternal mortality, both STD treatment and emergency obstetric care appeared to be very cost-effective compared with alternative types of health intervention, despite their very different costs per patient. In the World Bank's preliminary estimates, each could generate an additional DALY for the population at a cost of under $20.

Such estimates rely on sketchy data for key parameters of both costs and effectiveness, and so they should not be pushed for fine distinctions among types of programs. But the World Development Report analysts found that many types of interventions differed in their estimated cost-effectiveness (cost per DALY) by orders of magnitude. However, even given the limitations of the method and the data available, in Bobadilla's view, such analyses are useful in challenging the often implicit rules under which allocation decisions have been made in the past. For example, it is not true that preventive measures are always more cost-effective than curative ones, nor that cheap measures (on a per capita basis) are more cost-effective than those using more resources for a subset of the population, nor that the measures directed against high-prevalence disease are always more cost-effective than those directed against low-prevalence diseases or conditions. Both cost and effectiveness in reducing the disease burden have to be taken into account. Efforts to control acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) are among the most costly elements of the package recommended in the World

Development Report for low-income countries, but they also appear to be among the most productive. Efforts to improve safe delivery are likewise very costly but have high potential effectiveness and thus appear among the most cost-effective investments in the health sector under a wide range of conditions.

To improve the usefulness of such models for health sector planning, Bobadilla recommended data collection to support more reasonable estimates for some of the large and variable cost items (salaries, pharmaceuticals, and overhead costs of facilities and equipment), along with research and estimates of the range of effectiveness of different interventions. Analysts, in his view, should test a wide range of estimates in their models and perform sensitivity analyses, so potential users will be aware of how much the qualitative results depend on particular assumptions.

The models developed for the World Development Report (like those used to produce cost estimates discussed at the ICPD) used average costs, not marginal ones. Much of the methodological debate surrounding this work has hinged on the appropriateness of discounting and the choice of a discount rate, that is, the relative weight assigned to costs incurred and benefits realized in future years compared with the present. In Bobadilla's view, the practical conclusions are little affected by discounting considerations.

Several participants felt that the models in the World Development Report are too optimistic about effective demand for services, especially for relatively new reproductive health interventions. Allan Rosenfield noted the problem of “silent diseases” like reproductive tract infections, which cause a great deal of suffering, although women do not complain or seek treatment for them, apparently because many assume that the symptoms are “normal” and that nothing can be done for them. Future work on the costs of reproductive health interventions, in the view of several participants, should incorporate greater expenditures for information, education, and communication programs to raise awareness of the health problems for which something can be done and to legitimize health-seeking behaviors.

There was also some discussion of the sensitivity of estimates of the effectiveness of programs of infectious disease control to assumptions about the dynamic effects of the interruption of disease transmission, that is, the program's effect on future morbidity and mortality among persons who have not yet contracted a disease. Primary and secondary prevention of STDs other than HIV infection is much more attractive when, as in the World Development Report work, HIV prevention is included as a benefit rather than only the reduction of morbidity due to the disease directly targeted.

Barbara Janowitz, commenting on the approach taken by the World Development Report, noted that there is no single “family planning package” that can be inserted into cost-effectiveness estimates. She questioned some of the assumptions about the method mix for postpartum family planning services that the World Bank group had made, noting that its estimates of the costs of contracep-

tive supplies seemed high. Decisions about the right mix of inputs for family planning have to be made, using whatever information can be produced about likely costs and effects on the quality of services. An example is whether the recommended number of revisits to the clinic after IUD (intrauterine device) insertion can be reduced (Janowitz et al., 1994). Nor can costs be assumed to be the same in the private and public sectors.

Janowitz raised the crucial issue of assumptions about the efficiency of service delivery that are required for cost-effectiveness estimates. To estimate the inputs that will be required to add new reproductive health services to a standard family planning program, one must ask the question, “How busy are the workers now?” In many countries, even those in which resources are clearly inadequate for health “needs,” existing facilities are underused; Janowitz cited the examples of operating theaters in hospitals in Bangladesh that are closed because surgeons are not available, community-based distribution workers who work far fewer hours than their job descriptions call for, and other examples. In such cases, better management could lead to considerably greater service output from the same amount of inputs (numbers of providers and facilities and equipment). But increasing efficiency in this way is not costless, Janowitz cautioned; it requires profound changes in management and supervisory styles and the disruption of routines. Higher salaries might have to be paid to managers and workers alike to attract and keep the right staff and to overcome the lethargic culture of many public bureaucracies. So for cost estimates, it would probably be a mistake simply to assume that adding new reproductive health services requires proportional increases in all inputs—but it would also be a mistake to assume that workers and facilities currently operating below capacity could produce additional services with only a little extra training. The incremental costs of new reproductive health services would lie below the average costs for existing family planning services—but they would not be zero.

Antenatal and delivery care were treated as a single intervention for these estimates, because much of the value of antenatal care consists in imparting information about warning signs of premature or complicated labor and about appropriate delivery care. Participants in the workshop agreed that in the past too many antenatal care interventions had introduced screening for high-risk pregnancies when there were no useful facilities to which women could be referred and no backup for the first-level providers. Programs had overemphasized the training of traditional birth attendants and underemphasized provision of emergency obstetric care, and little reduction of maternal mortality ratios had been achieved as a result of these efforts. Rosenfield made a related point about Pap smears: screening, even when highly sensitive and specific tests are available, is of little use if the requisite treatment is not available.

Nutrition interventions for pregnant women were not separately considered in these models (although iron and folate supplementation was included in the standard package for antenatal and delivery care). Bobadilla noted that the nutri-

tion literature does not provide a strong basis for saying that prenatal macronutrient supplementation produces an effect on the long-term health of the child.

There was also discussion of potential sources of financing for new initiatives in reproductive health care. Bobadilla noted that the 1993 World Development Report had recommended public financing of a package of basic services. Janowitz called for more studies of costs and financing and how they vary within a country: What do services cost, and who is paying for them now? The World Bank estimates presented by Bobadilla and Cowley showed a package of essential reproductive health services costing about 20 percent of current health care expenditures in Mexico and 25 percent in Ghana, but 66 percent of current health care expenditures in Tanzania.

Quality Assessment and Assurance

Both in family planning and in other health sectors, and in rich as well as poor countries, there has been a resurgence of interest in recent years in ways to assess and improve the quality of services provided. In a presentation on the quality of reproductive health services, Beverly Winikoff cited a useful framework proposed by Judith Bruce (1990) for thinking about the quality of family planning services. Bruce lists six elements of the quality of care: (1) the availability of a choice of contraceptive methods, (2) the provision of information to clients, (3) the technical competence of providers of services and information, (4) the interpersonal relations between client and provider, (5) mechanisms to ensure continuity of service, and (6) the appropriate constellation of services. Although the headings can be rearranged and different indicators chosen to operationalize aspects of quality, most working definitions and studies of family planning have used some variant of Bruce's categories.

Winikoff drew on the results of “situation analyses” of family planning services conducted by the Population Council and collaborating institutions in several countries (see, for example, Miller et al., 1991, and Mensch et al., 1994). The linked elements of situation analysis are observation of service delivery, discussion of quality with clients, and discussion of quality with providers. Not only is situation analysis an instrument for measurement, but it is also intended as an intervention in its own right, building up discussion and awareness of the quality of services. Winikoff illustrated its usefulness with results from studies in Tanzania and Nigeria, which showed shortcomings in both method choice and technical competence. For example, counselors dealt far more often with information about resupply than with information on how to use contraceptives effectively. Providers did not ask whether potential clients were breastfeeding.

Winikoff discussed the difference between clients' and providers' (and researchers') perceptions of quality. Standardized questionnaire items eliciting clients' overall judgment of quality (e.g., “Would you return?” “Would you recommend this clinic to a friend?”) are not of much use, Winikoff reported,

since courtesy bias produces very high positive ratings even from clients who talk quite freely about important defects when asked more specific or open-ended questions. When asked to define good quality of services, clients in Chile referred mainly to interpersonal aspects of care—clean clinics, no cigarette smoke in the waiting rooms, respect from staff, and learning something about their bodies and health. Clients tend not to mention the technical competence of staff. Much of the advocacy for improving quality of care has been an outgrowth of consumerism. In both research and advocacy, more attention has been paid to the interpersonal aspects of care than to problems with technical competence, and Winikoff argued for increased attention to the latter.

Winikoff discussed problems of technical competence and interpersonal relations in maternal health services. Almost all maternal deaths, she noted, are preventable. The enormous differences in mortality rates are due to poor women's not getting some well-defined life-saving services. Winikoff used Deborah Maine's distinction among the “three delays”: delay in the decision to seek care, delay in getting to an adequate facility, and delay in getting the right service after presentation at a facility (Maine, 1990). A large number of deaths occurs at this third stage, Winikoff stated, even though this should be the stage most under the control of the health care providers—a situation that signals the need for concern with the technical quality of emergency obstetric care.

The problems of access and quality of care may well be linked for abortion and emergency treatment of the sequelae of abortion. A study in Argentina showed that even legal and mandated services can be abusive and accusatory. Winikoff cited studies in Brazil showing poor technical quality of care—the wrong intravenous fluids used, wrong decisions about procedures (Costa and Vessey, 1993). In many countries, including India, induced abortion is legal under various circumstances, but many hospitals have no provisions for referrals or for performing the procedure; for many women, the right to a safe abortion exists only de jure, not de facto. The introduction of manual vacuum aspiration, safer for first-trimester abortions than the dilation and curettage procedure, should be an opportunity to improve the entire service.

Winikoff also noted that the postpartum period provides an excellent opportunity for service integration. Postpartum family planning should not be seen as just a device for increasing contraceptive prevalence rates cheaply; she gave the example of a study in Mexico showing that the introduction of low-dose oral contraceptives into a postpartum service, even though popular with clients, was ended because it reduced the number of women choosing long-term methods. This decision, in Winikoff's view, stemmed from a narrow concept of cost-effectiveness, which did not take sufficient account of how well different contraceptive methods meet women's particular needs.

Wayne Stinson discussed the experience of the Quality Assurance Project and how lessons learned in the health sector generally could be applied to im-

proving the quality of reproductive health interventions. He organized the presentation around four issues:

-

What constitutes quality assurance in reproductive health programs?

-

How important is quality under conditions of severe resource constraint?

-

Who “owns” quality?

-

How much can be done within vertical program interventions?

He urged participants to think of quality assurance as a set of activities, including quality design, quality control or monitoring, and quality improvement. He proposed organizational changes that inculcate a continuous search for opportunities for improvement, rather than efforts that focus on identifying problems and punishing malefactors.

Quality design is the specification of essential programmatic and service delivery characteristics and the development of structural, process, and outcome standards to achieve them. International specialists (among them the staff of the Quality Assurance Project) have identified dimensions of quality but, to be effective, these must be locally adapted and adopted, and individual managers must feel a sense of ownership and responsibility (Brown et al., 1991). There are many ways to control quality, through routine monitoring or periodic assessments, but most current systems are managed by those well above the service delivery level. There is a great need, in Stinson's view, for simple and replicable monitoring techniques, including self-assessments and peer review (for an example of the latter from Indonesia, see MacDonald et al., 1995). Quality assurance should not be treated as a research activity but as a routine management responsibility. Efforts to improve quality used to depend on material inputs and relatively scarce technical expertise, which led many decision makers to think of quality as unaffordable in poor countries. Specialists now concentrate on simplified problem-solving techniques and empowering district managers to use them routinely (Franco et al., 1994).

Higher-quality services are often more cost-effective, and may even cost less, than lower-quality ones. This is especially so, Stinson claimed, if the “invisible costs” of poor quality (such as development of antibiotic-resistant organisms) are taken into account. Quality improvements can increase consumers' willingness to pay for services and may be a necessary prerequisite to any attempts to increase sustainability through cost recovery.

Health-sector managers may nonetheless face real trade-offs between quality and coverage. They cannot simply choose to expand coverage of public services all the time, despite strong external pressures to do so. There are some services that are best not done at all if they cannot be done correctly, such as injections, multidose immunizations, and antibiotic treatments. At the same time, choices have to be made between maximizing the quality of individual case management and the quality of the program as a whole, viewed as impact on public health. As

professionals serving the entire community, those responsible for public health programs have to consider the needs of the total population in need, both “clients at the door” and those not yet reached.

Quality problems are pervasive in reproductive as in other health programs, and it makes little sense, in Stinson's view, to segregate activities into separate family planning and health “boxes.” Most quality problems relate to clinic management, deployment of staff, supervision, lack of monitoring, and poor relationships between communities and health care providers. Stinson referred to two projects in Niger, one working with district and regional management to institutionalize quality assurance, and the other a national family planning project. Most of the differences between the two in quality assurance had to do with location and organizational level rather than technical content. Both projects set standards, train personnel, strengthen supervision, and struggle with problems of worker motivation and clinic management. There has been little interaction between the health and family planning communities on quality issues, but this will need to change as they move past the stage of simply defining and measuring quality.

Provider-client interaction is central to reproductive health services, according to Christopher Elias, who commented on Stinson's presentation. Any attempt to improve quality that does not have an effect on providers ' behavior in those interactions means little. But Elias was also concerned that an exclusive focus on providers can often mean that front-line providers are simply blamed by those higher up for deep-rooted failings of the entire system.

Service Integration

Integration of services is generally considered a good thing, and for a variety of reasons: greater coordination of services, ease of referral, convenience to the clients, and reduction of administrative and other shared costs. But integration, like other good things, has its costs as well, and managers of programs must decide how much of it, and which types, are worth the effort; the general injunction to integrate and coordinate is not a sufficient guide to action.

Pierre Mercenier drew on experience in several types of health services for guidelines that could be useful for those who must decide whether to add new reproductive health services to the repertoire of existing organizations and providers or to seek specialization. He began by noting the characteristics that define general health services as they exist in both rural and urban areas: they offer comprehensive services, have continuous contact with the population (at least those near enough to a facility to be served), and are for the most part adapted to local felt needs. Most contacts are initiated by the clients for relief of symptoms. In contrast, many preventive or vertically organized public health programs are introduced, not in response to needs expressed by those who currently present at health care facilities, but in response to opportunities or man-

dates perceived by those in charge of the services, who must convince both potential clients and the front-line providers that the new service is worthwhile.

Mercenier distinguished “administrative integration” from “operational integration.” He once found in a West African country, for example, that a leprosy control program relied on special-purpose leprosy workers who operated entirely independently of the rest of the health services. But this program was deemed by the regional office of the World Health Organization (WHO) to be integrated because the leprosy workers reported to the district medical officer: in Mercenier's terms, this program may have been administratively integrated but was not operationally integrated with the other services. If a program is operationally integrated with general health services, then it must also be administratively integrated. If it is not operationally integrated, then whether or not there is administrative integration matters little, according to Mercenier.

Operational integration is sometimes chosen by default, because mounting a vertical program is deemed too expensive. At other times, integration is selected to achieve better access for the new program, taking advantage of the existing facilities and providers and their acceptance by the population to be reached.

A specialized program fares best with integration when the technology requires frequent contact with the clients, as, for example, does chemotherapy for tuberculosis, and when the service responds to a need felt by the local population and is seen as important by the health workers. This is a problem for programs aimed at diseases with low prevalence, such as leprosy. But leprosy control is also a good example of a program with much to gain from integration with the general health services, since there is some stigma attached to the disease. The easiest programs to integrate are those relying on standardized skills that can be taught to multipurpose health workers. Integration of a new program into the general health services works well when it brings visible results and the new skill increases the confidence of the workers and of the community. These positive attributes make many proposed reproductive health initiatives good candidates for integration into general health services.

Integration works less well when precise operational targets have to be met within a short time, as with EPI (Expanded Programme on Immunization) programs, because they take workers away from what they and their clients consider their primary tasks, often not in response to an immediate need perceived by the client. For example, malaria control programs in several Indian states were designed so that surveillance would be a continuing responsibility of the general health services. But this assignment was made just after the vertical program had brought endemic malaria under control—that is, just when the need for malaria control was not felt by the local populations and health workers.

There is a price to be paid for integrating a program rather than maintaining it as a vertical one. Some technical proficiency may have to be sacrificed. There is also a compromise in data collection, since general health workers can quickly be overburdened by reporting requirements. Integration, Mercenier concluded, is

often useful, but not a panacea. If proponents of reproductive health interventions want to realize the gains from integration, then they will do best to accept the defining characteristics of the general health services and look for areas of commonality.

Ruth Simmons raised further questions that need to be addressed in assessing the balance of costs and benefits of operational integration. Is it a matter of bringing together some existing services or adding new ones (and if the latter, are new resources to be made available or will job descriptions simply be rewritten)? And at which precise levels of the service are new tasks to be added?

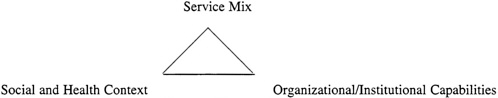

She described a simple framework that the WHO Task Force on Contraceptive Introduction and Technology Transfer has found useful:

All three apices of this triangle—the service mix, the social and health context, and organizational and institutional capabilities—have to be considered in any proposal for integration.

The social and health context includes not only needs as defined by professionals, but also needs felt by the intended clients. One has to listen carefully to the voices of the users, something that is not commonly done in family planning (or in most other public services). Often users express needs for particular combinations of services. Simmons gave examples from the family planning program in Vietnam, which relies heavily on IUDs. The family planning clinics can provide initial treatment for reproductive tract infections, but women are then reluctant to follow up the referrals to health clinics, since they know that the health workers will usually advise removal of the IUD while the infection is treated. The excessive reliance on IUDs can thus interfere with the goal of treating reproductive tract infections. To cite other examples, many polyclinics offer menstrual regulation but not contraceptive services, and condom promotion has been transferred from family planning to HIV programs, as has happened in several other countries, and the availability of methods has suffered on both accounts.

With each proposed expansion of services, one must ask the difficult questions about feasibility. Failing to do so can lead to designs of comprehensive services that look good on paper but do not in fact do many of the things that are advertized. “Requisite organizational capabilities to implement complex service packages or to ensure administrative integration and interagency coordination are rarely present” (Simmons and Phillips, 1987:204). There is no guideline for how

this must be done, since much depends on organizational history, culture, and resources. Comprehensiveness and complexity must often be balanced with quality of service. Simmons cited the example of a recent plan by the Vietnamese Ministry of Health to introduce implantable contraceptives. A government team sponsored by the World Health Organization recommended against implementation of the plan at this time, since existing family planning and reproductive health services did not seem capable of ensuring acceptable levels of quality.

Sandra Kabir described in her presentation an example of how family planning and other reproductive health services were built up by a nongovernmental organization (NGO), the Bangladesh Women's Health Coalition (BWHC).2 The BWHC had started offering abortions when restrictions on funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development had caused other NGOs to stop providing abortions. Later, BWHC added family planning (in part so that women using the abortion services would not be conspicuous) and child immunizations. The 10 BWHC clinics also treat large numbers of cases of respiratory, gastrointestinal, and skin infections. The nonreproductive health services were added to the package, not because of a policy decision to integrate services, but in response to requests from clients. This has extended even beyond the health sector, as some of the clinics organize women's literacy programs, and many clients seek referrals to sources of legal assistance or credit. Treatment of reproductive tract infections (chlamydia being most common) is being added now, as staff are being trained.

The lessons Kabir drew from the BWHC experience included that services should be available at times when women can use them conveniently; services for women should be available in the same places as some services for children (since Bangladeshi women will often seek care for themselves only during a visit for the more socially approved purpose of seeking services for the children); and that reproductive health services should not be separated from other services, as for example with separate waiting areas, so as not to stigmatize clients. She noted that an important function of NGO clinics is to demonstrate what is possible, so that government health services can be emboldened to innovate. NGOs in general can influence policy by having representatives serve on national committees (e.g., the ICPD delegations and national AIDS committees) and by exerting pressure for health sector reform and quality improvements and changes in legal systems.

Willard Cates elaborated on the theme of organizational cultures, with illustrations from family planning and STD control programs (Cates, 1993). In family planning, providers typically believe that they should be presenting options to clients, whereas providers at STD clinics are far more directive. Clients at family planning clinics are taking action for the future, whereas STD clients are most

|

2 |

The BWHC is also described in a 1991 publication of the Population Council (Kay et al., 1991). |

often seeking care for immediate symptoms. There can be “two-way stigmatization,” as those responsible for both family planning and STD control assume that their clients will not want to mix in clinics with the clients of the other program.

When integration is being urged on existing services, then separate power structures can be involved in effective resistance. The example Cates gave was the attempt in the 1980s in the United States to link AIDS control with STD programs; the two had separate staffs in state and local government, as well as separate sources of federal funding. In some states the merger was successful, and in some it never happened.

There have been some notable successes in service integration, according to Cates. In the United States in the 1970s, intensive screening for gonorrhea in family planning settings proved effective. Chlamydia control based on screening in family planning clinics has also showed impressive results in many areas. Cates felt that the linkages with family planning have probably brought into STD control a greater concern with the interpersonal relations with clients.

Beverly Winikoff pointed out that, in most developing countries, enhancing treatment of reproductive tract infections or linking safe abortion to contraceptive services would not involve merging existing bureaucracies, since these typically do not yet exist. It is not so much a matter of integrating as of rethinking existing services. In Winikoff's view, there is a “service vacuum” for postpartum women, an opportunity for sensible integration of services. Women express a range of needs—for the baby's care, for their own health, for fertility control—but these either do not exist or are needlessly inconvenient and poorly publicized.

Several participants discussed the trade-offs between comprehensiveness of services and technical quality of care. Barbara de Zalduondo recommended development of lists of minimum sets of reproductive health skills required by providers at different levels (comparable to the WHO guidelines for services that should be available at facilities at different levels of a referral system). Judith Wasserheit noted the tension between loading too many tasks onto a single provider and having them overspecialized in particular organ systems. One can have vertical programs, according to Huda Zurayk, but not “vertical providers,” since clients will always present multiple problems. Wayne Stinson felt that the problem of excessive specialization can be exaggerated, especially since systems that have such specialists can often implement reasonable referral systems. Allan Rosenfield noted that certain types of integration make sense in terms of providers ' skills and training. For example, in clinics in which the staff have been trained to insert IUDs, the addition of the treatment of abortion complications makes sense. Similarly, staff trained to provide female sterilization can also be trained in the management of abortion complications and, if the necessary equipment and supplies can be provided, can provide emergency obstetrical care.