2

Defining U.S. Interests

SUMMARY POINTS

-

The major factors that contributed to predictability and smooth management of the U.S.-Japan relationship during the Cold War are now largely gone. However, there are compelling reasons why maintaining the security alliance remains an important interest for both countries. Due to the correspondence of fundamental interests between the two countries and the importance of the U.S. market for Japan’s economy, in addition to the U.S. security guarantee, the United States continues to enjoy leverage in the relationship.

-

Shifts in the geopolitical environment and in the relative economic strength of the United States and Japan mean that the conduct of the relationship will inevitably change. Indeed, elements of the partnership have changed in recent years, mainly because the United States has begun to seek greater reciprocity in the relationship and the common Soviet threat has dissipated.

-

Opportunities exist for the United States and Japan to build a stronger alliance as part of expanding regional institutions and discussions on security and in addressing global problems. However, the lack of a focused common threat, uncertainties about the future, and different perspectives on economic issues could lead to a cooler, more acrimonious relationship.

-

Although there are a number of uncertainties concerning the security environment surrounding the U.S.-Japan alliance, the Defense Task Force believes that the time has clearly passed when defense cooperation featuring primarily one-way transfers of technology from the United States to Japan could be justified by U.S. security interests.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

In the coming decades the United States and Japan will face a global security environment that is radically different from the one that prevailed during the Cold War. For most of the post-World War II period, the U.S.-Japan security relationship has been managed by specialists in each government in a fairly straightforward manner. The nature of “trade-offs” in the relationship and the terms of trade were stable and mutually understood. Two factors contributed to this stability. The first was an international environment in which key features, most importantly the Soviet threat, remained consistent over time. As a result, both the United States and Japan had a clear understanding of their own interests and intentions in the relationship, and each viewed the interests and intentions of the other as fundamentally compatible with its own. Consistency in the international environment contributed to predictability in the U.S.-Japan relationship.

The second factor was the basic asymmetry in the assets that each side brought to the relationship. Until fairly recently, Japan contributed mainly political assets (its importance as a strategic partner), while the United States brought economic, military, and technological assets.

As long as Japan’s contribution was highly valued by the United States and America enjoyed a preponderance in economic, military and technological power vis-à-vis Japan, this asymmetry facilitated stable and mutually agreeable patterns of bargaining and trading.1

Although the United States encouraged the adoption in 1947 of Japan ’s “Peace Constitution,” which contains in Article IX a renunciation of war as a sovereign right of the state, by 1950 concerns about Soviet military power and intentions had led the United States to alter its stance. From that time the major thrust of America’s Japan policy was to work toward solidifying Japan’s membership in the “Western” camp allied against Soviet expansion. One element of this policy involved encouraging Japan to increase its industrial and military capabilities. Another element was to work to ensure domestic Japanese political support for a continued U.S. military presence in Japan. U.S. forward deployment in Northeast Asia became important with the fall of China and the outbreak of the Korean War, and it has remained so. Japan became the key strategic partner for the United States in Asia, and the relationship has been seen as central to long-term Asian stability.2

Japanese policy has accommodated these American objectives. While opposition to large scale rearmament in Japan has continued over the postwar period, limited rearmament enjoyed initial support among Japanese conservatives, and the Self Defense Forces have gained greater public acceptance over time. The alliance with the United States and the stationing of U.S. forces in Japan have attracted vocal opposition in Japan at times. However, the alliance has generally enjoyed support across a range of policymakers and opinion leaders in Japan, as well as generally increasing support (or at least acquiescence) from the general public.

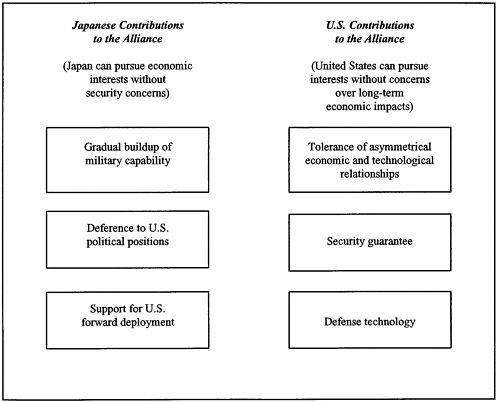

The Japanese conservatives of the Liberal Democratic Party, who enjoyed parliamentary majorities continuously from 1955 until 1993, pursued a policy of supporting the U.S.-Japan alliance and gradually increasing Japan’s military capabilities.3 Consistent support for the alliance, general acquiescence to U.S. political leadership in major international issues, and a forward position near the Asian land mass were the primary Japanese contributions to the U.S.-Japan relationship. In return the United States provided a security guarantee to Japan and tolerated asymmetrical economic and technological relationships because they were seen to advance overall U.S. interests.

Figure 2-1 illustrates the fundamental trade-offs in the relationship up to about 1980. From the standpoint of U.S. interests, the two salient points about this structure were (1) U.S. politico-military interests drove overall national strategy and policy toward Japan, and (2) in pursuing these interests, there was almost no opposition in the United States to trading off economic and technological assets, because prior to the late 1970s the United States was presumptively stronger than Japan economically and technologically.

During most of the 1950-1980 period, achieving market access and other concrete forms of economic reciprocity with Japan were not seen as important U.S. interests. Indeed, particularly in the early postwar years, providing economic and technological benefits to help build Japan into

|

1 |

Originally and as revised in 1960, the security relationship itself is fundamentally asymmetrical; the United States is obligated to come to the defense of Japan if the latter is attacked, but Japan is under no such obligation if the United States is attacked. |

|

2 |

See U.S. Department of Defense, United States Security Strategy for the East Asia-Pacific Region (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1995), particularly p. 10. |

|

3 |

Conservative rule even preceded formation of the LDP. Except for a brief period when the Japan Socialist Party led the government, conservative parties held power in Japan from the time that elections were resumed during the U.S. occupation. |

FIGURE 2-1 The U.S.-Japan relationship: Cold War status quo.

an Asian “bulwark of democracy” as a key component of Western economic muscle was seen as advancing fundamental U.S. strategic interests and was not perceived to be associated with any particular long-term costs. The United States followed a conscious policy of encouraging Japan’s participation in the alliance by providing extensive economic benefits during the 1950s, benefits that provided a short-term boost to the Japanese economy and helped lay the foundation for rapid growth over the next several decades. Examples include providing access to the U.S. market and supporting Japan’s membership in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade while tolerating restricted access to the Japanese economy and the U.S. military’s “special procurement” of Japanese automobiles during and after the Korean War.4In addition, the U.S. government generally did not exert pressure on behalf of U.S. firms trying to break into the restrictive Japanese market during the 1950-1980 timeframe, even though such pressure would probably not have impaired the security relationship.5

Prior to the emergence of large bilateral trade deficits with Japan and the strong competitive pressure from Japanese firms on the U.S. consumer electronics, auto, and semiconductor

|

4 |

See Jerome B. Cohen, Economic Problems of Free Japan (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University, 1952). Also, Robert A. Pastor, Congress and the Politics of U.S. Foreign Economic Policy: 1929-1976 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980), p. 98; Eiji Toyoda, Toyota: Fifty Years in Motion (New York: Kodansha International, 1985). |

|

5 |

See Mark Mason, American Multinationals and Japan (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1992). |

industries during the 1970s and 1980s, there was little interest among U.S. opinion leaders or the general public in U.S.-Japan trade or technology issues. Economic interests were not only subordinate, they were conceptualized in a different way than many Americans conceptualize them today. Reciprocity was not a consideration. There is still considerable debate and disagreement within the United States over exactly what our economic interests are in relations with Japan and how to go about pursuing them.6

Just as the structure of the U.S.-Japan security relationship during most of the Cold War appears, at least in retrospect, to have been relatively straightforward, so does the role of military technology. The transfer of military technology from the United States to Japan represented an inducement for Japan to rebuild its defense industrial base and procure systems consistent with an expanding defense capability within the framework of the alliance. Along with “off-the-shelf” purchases from the U.S. companies, Japan has produced a variety of aircraft and other U.S. weapons systems under license. While more expensive than exclusive reliance on purchases would have been, Japan has developed a relatively strong defense industrial base and dual-use technology base without making the large expenditures on indigenous systems that other U.S. allies, such as Great Britain and France, have made. U.S. arms makers have benefited from sales and licensing income, and Japanese industry has been a potent interest favoring expanding defense budgets and procurement.

Changes During the 1980s

Of the two factors that served as a foundation for easy management of the U.S.-Japan security relationship—the stable international environment and the disparity in U.S. and Japanese capabilities— it was the latter that shifted first. It took until the early 1980s for the change in relative power to register on the conduct of the relationship. The changes did not immediately affect the outcome of major decisions but instead were reflected in contentious debates over matters that had not been debated previously and in heightened interest in U.S.-Japan issues on the part of nonspecialists.

One interesting indicator of the suddenness in the change in thinking concerns Japanese licensed production of the F-15 fighter. When the U.S. government originally considered the issue in the late 1970s, most of those holding reservations were concerned with possible leakage of technology to third countries rather than economic competitiveness or unbalanced technology flows.7 As a result, while the outflow of technology was carefully controlled, there were no technology flowback provisions written into the original government-to-government agreement. But by 1982, in recognition of the dramatic gains made by Japan in several important manufacturing industries, a U.S. General Accounting Office report explicitly raised the concern that F-15 technology transfers would help Japan develop a commercial aircraft industry that

|

6 |

A substantial segment of U.S. opinion, including many professional economists, holds that notions of competitiveness and reciprocity are not useful constructs for formulating U.S. economic policies and approaches to international economic relations. See Paul R. Krugman, “Competitiveness: A Dangerous Obsession,” Foreign Affairs, March/April 1994, pp. 28-44. The opposing view is represented by Laura D’Andrea Tyson, Who’s Bashing Whom? Trade Conflict in High-Technology Industries (Washington, D.C.: Institute for International Economics, 1992). |

|

7 |

The concerns in the interadministration debate were traditional ones, mainly the risk that sensitive technology would leak to the Soviets. See Michael Chinworth, Inside Japan’s Defense (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s (US), Inc., 1992), p. 108. |

could one day compete with the United States. Flowback provisions were then written into the agreement. In the intervening years, expanding Japanese trade surpluses and the rapid gains made by Japan’s auto industry in the U.S. market raised America’s awareness of Japan’s economic and technological strength.

The increased Cold War tensions of the early Reagan years and the Nakasone cabinet’s policy of pursuing a greater Japanese burden-sharing role in the security relationship served to ameliorate the impact of growing economic rivalry. One illuminating example that involved balancing U.S. economic and political-military interests, as well as divergent viewpoints over how economic interests should be conceived, is the 1983 decision of the Reagan administration to not take retaliatory action on a finding of unfair Japanese trade practices in the machine tool industry, following an appeal from Prime Minister Nakasone to the U.S. president. The U.S. political-military interest in the success of Nakasone’s policy of making Japan an “unsinkable aircraft carrier” of the West carried the day, buttressed by the argument that all market outcomes—even those that result from large foreign government subsidies and trade barriers—should be accepted.8

Improved U.S.-Japan cooperation in military and strategic areas, including the acquisition of important new capabilities and increased host nation support by Japan, could not prevent more frequent and contentious debate in U.S. business and policy circles over U.S.-Japan economic relations from affecting the security relationship. Routine management of the security relationship by specialists outside the political spotlight became increasingly difficult during the 1980s. When the strategic threat posed by the Soviet Union—the other factor underlying stability in the U.S.-Japan relationship—began to evaporate in the late 1980s, so did the logic of interests and trade-offs illustrated in Figure 2-1 (at least on the U.S. side). The contrast between U.S. decisionmaking in the F-15 and FS-X cases, particularly the heightened concerns expressed in the FS-X debate in 1988-1989 about the possible risks to U.S. leadership in the commercial aircraft industry posed by transfer of military aircraft technology to Japan, illustrated that security concerns were becoming subject to wider scrutiny and debate and that economic interests could no longer be controlled or ignored by those managing the security relationship.9

THE NEW ENVIRONMENT

Recent American and Japanese analyses are in general agreement about the key features of the Asia-Pacific security environment for the next several years.10 First, although the risk of great power conflict appears to be low at the present time, several of the world’s major military powers have vital interests in the region, meaning that global and regional security concerns are highly

|

8 |

Ironically, the U.S. government granted some trade relief to the U.S. machine tool industry several years later because of national security concerns about growing dependence on foreign, particularly Japanese, machine tools. See Clyde Prestowitz, Trading Places: How America Allowed Japan to Take the Lead (Tokyo: Charles Tuttle, 1988), pp. 223-229 and pp. 244-246. |

|

9 |

See Chinworth, op. cit., pp. 132-161. |

|

10 |

See Admiral Charles R. Larson, Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Command, United States Pacific Command: Posture Statement 1994 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1994) and Advisory Group on Defense Issues, The Modality of the Security and Defense Capability of Japan: The Outlook for the 21st Century, as translated in Patrick M. Cronin and Michael J. Green, Redefining the U.S.-Japan Alliance: Tokyo’s National Defense Program (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1994). |

interdependent and that the course of great power rivalries and interests will impact on regional and global security.11 The future political and economic development of Russia and China are two of the most significant long-term issues. The United Nations, the establishment by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) of the ASEAN Regional Forum, efforts to realize a limited nuclear free zone in Northeast Asia, and other institutions and mechanisms aimed at ensuring global and regional security could also have an impact, although there are significant challenges in building more effective multilateral institutions.

A second feature of the environment is the existence of a number of potential trouble spots in the region that could flare up in coming years, with risks somewhat heightened by ongoing weapons modernization programs in several countries and in some cases by the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. Some of these possible security challenges are left over from the Cold War. The Korean peninsula is the most obvious potential trouble spot in Northeast Asia. There are also several territorial disputes in East Asia, including the conflicting ownership claims to islands in the South China Sea. The relationship between Taiwan and China may also present security challenges.12

A third factor is the economic dynamism of much of the region, which is expected to continue and spread. Although progress in economic and political development will have beneficial impacts mainly in the long-term, economic rivalry of various forms between nations and perhaps groups of nations is also likely to grow and intensify. Currently, and for the foreseeable future, U.S.-Japan economic rivalry, along with some mutual concern about China, will be at the center of this trend. A key question is whether these rivalries and related disputes over trade, investment, and other issues can be managed to ensure that expanded commerce contributes to overall stability and security.

What are the implications of this environment for U.S. and Japanese security policies? In 1993, President Clinton articulated a vision for a New Pacific Community based on “shared strength, shared prosperity and a shared commitment to democratic values and ideals.”13 The security priorities for this New Pacific Community are (1) a continued American military presence in the Pacific, (2) stronger efforts to combat the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, (3) a flexible approach to cooperation that may include new regional security dialogues as well as maintaining strong bilateral relationships, and (4) support for democracy and more open societies. As indicated in bilateral relations with Japan, China, and Vietnam, as well as in efforts to build the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, the Clinton administration has placed U.S. economic interests at the forefront of initiatives in the region.

Japanese security policy still operates officially under the National Defense Program Outline (NDPO) of 1976.14 Although the process of political reform and realignment begun in 1993

|

11 |

For a wide-ranging analysis of security issues and future scenarios for the region, see Richard K. Betts, “Wealth, Power and Instability: East Asia and the United States After the Cold War,” International Security, Winter 1993-94, pp. 34-77. |

|

12 |

See “China: New Menace or Misunderstood Miracle,” Far Eastern Economic Review, April 13, 1995, pp. 24-30. |

|

13 |

See William J. Clinton, “Remarks by the President in Address to the National Assembly of the Republic of Korea,” July 10, 1993. |

|

14 |

For an English translation of this document, see Japan Defense Agency, Defense of Japan 1994 (Tokyo: The Japan Times, 1994), pp. 259-264. At this writing, it was not clear whether the Japanese government would replace the NDPO or when this might happen. News reports in the spring of 1995 indicated that JDA planners were preparing a draft for review by the cabinet. See “Kagaku Tero ni mo Sonae” (Even Provisions for Chemical Terrorism), Nihon Keizai Shimbun, April 16, 1995, p. 1. |

continues, several important developments have occurred recently. 15 Perhaps most significantly, the Social Democratic Party of Japan (SDPJ) reversed two long-standing policy positions shortly after the formation of the Murayama cabinet in July 1994. The SDPJ now recognizes the Self Defense Forces as constitutional and favors continuation of the U.S.-Japan security treaty. These positions are now baselines in Japanese politics, agreed to by all major political forces except the Japan Communist Party.

Over the next few years the direction of Japanese security policy is likely to involve debate among several schools of thought.16 One line of thinking, whose best-known advocate is Representative Ichiro Ozawa of the newly formed Shinshinto, or New Frontiers Party, envisions Japan developing into a “normal country” that plays an international role in political and military affairs commensurate with its industrial and financial strength. Most of those embracing this view favor a strong U.S.-Japan alliance but also advocate a significant boost in the capabilities of the Self Defense Forces, including those required for peace-keeping activities.

Another group, while favoring a Japanese role in U.N.-directed peace-keeping operations, would prefer that Japan’s defense capability be maintained at a minimum level, perhaps even be cut or restructured, rather than significantly expanded, with some favoring creation of a non-SDF force to assist in emergency responses and natural disasters. Reliance on the alliance with the United States would continue. This group, which bridges a number of political parties and encompasses many subtle and not-so-subtle differences on policy specifics, envisions Japan’s future role in global affairs as a “civilian power” to evolve on a trajectory from the present. The concept of “comprehensive security,” which has developed in Japan over the past several decades and emphasizes development assistance, investment, and other nonmilitary means of pursuing national interests in world affairs, would be embraced by many in this group.17

As mentioned above, recent changes on the Japanese left have substantially marginalized those who would favor ending the U.S.-Japan security relationship, scrapping the Self Defense Forces, and pursuing some form of unarmed neutrality. Although some on the left might be active in pursuing a limited nuclear free zone in Northeast Asia or other initiatives, the more interesting developments in the coming years are likely to occur on the right.18 During the Cold War, some measure of dissatisfaction with aspects of the alliance with the United States among the Japanese right (including conservative mainstream politicians such as former Representative Shintaro Ishihara as well as ultranationalist fringe groups) was subsumed under even greater antipathy for the Soviet Union. The absence of a Soviet threat made it possible for many members of the LDP to favor forming a coalition government in 1994 with their long-standing enemies in the SDPJ. Whether a significant group of Japanese conservatives stakes out a position seeking greater independence from U.S. foreign policy positions will be an important barometer to watch over the next several years.

|

15 |

For an overview, see John E. Endicott, Japan, the Japanese and the World (McLean, Va.: Brassey’s Inc., forthcoming). |

|

16 |

See Michael J. Green and Richard J. Samuels, Recalculating Autonomy? Japan’s Choices in the New World Order (Seattle: National Bureau of Asian Research, 1994). |

|

17 |

Sogo Anzen Hosho Kenkyu Gurupu, Sogo anzen hosho senryaku (A Strategy for Comprehensive National Security) (Tokyo: Okurasho Insatsukyoku, 1980). |

|

18 |

This is not to imply that a limited nuclear free zone would be supported only by the Japanese left; the initiative could potentially draw support from a fairly wide spectrum in Japan. |

IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S. INTERESTS

While predicting or prescribing the future course of the U.S.-Japan security relationship is beyond the scope of this particular study, setting U.S. goals and policies for maximizing U.S. security interests in our scientific and technological relations with Japan requires a basic conception of those interests and some understanding of how the security relationship might evolve in the future.

Although it is currently not as essential to the security of either country as it was just a few years ago, the U.S.-Japan security alliance —with some of its explicit and implicit asymmetries—is very likely to be maintained since it clearly continues to serve the fundamental interests of both countries.

For the United States, the alliance and the presence of U.S. forces in Japan demonstrate the continuing commitment to the security of the entire region. Fundamental U.S. interests in Asia-Pacific security include (1) denying control of the region to a hostile power or coalition; (2) maintaining and enhancing U.S. economic access to the region, which is the fastest growing in the world; (3) guaranteeing the security of sea lanes vital to the flow of Middle East oil; and (4) promotion of democratic values and human rights.19 In the short term, Japan is perhaps the only country with the economic and technological capabilities to constitute itself as a power able to overturn the Asian regional balance. A strong U.S.-Japan alliance helps prevent a significant expansion of the Japanese military, including acquiring a nuclear arsenal, and discourages Japan from assuming a political stance opposed to that of the United States. In the longer term, a continued U.S.-Japan alliance would serve to balance the emerging power of China, a resurgent Russia, or North Korea.20

Further, the security alliance with Japan does not impel the United States to spend anything on defense that it would not be spending anyway. Some would assert that it allows the United States to maintain its strategic position in Asia at reduced costs.21 Also, Japan’s increasing direct and indirect contributions to the alliance and global security should not be overlooked. In addition to the relatively high level of host-nation support that Japan provides for U.S. forces stationed there and Japan’s financial contribution in support of Desert Storm, these contributions include increased aid to strategic U.S. allies such as the Philippines and Turkey during the 1980s, growing financial contributions to the United Nations, participation in peace-keeping operations in Cambodia and elsewhere, and “behind the scenes” support for various U.S. positions and initiatives. Some analysts also believe that the flow of portfolio and direct investment capital from Japan to the United States during the 1980s and early 1990s helped hold down U.S. interest rates and provided needed resources for productive investments.22 The continuation of a strong

|

19 |

U.S. Department of Defense, op. cit., especially pp. 5-7. It should be noted that there are those who argue that U.S. security commitments in Asia do not enhance economic access, and may indeed serve as a restraint on the aggressive pursuit of market access. See David B. H. Denoon, Real Reciprocity: Balancing U.S. Economic and Security Policy in the Pacific Basin (New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 1993). |

|

20 |

See Betts, op. cit. |

|

21 |

In any alliance the benefits of sharing burdens with allies come with the obligation to consult and coordinate, implying some constraint on pursuing independent foreign policy initiatives. |

|

22 |

Others point out that Japan’s rise to the world’s largest net creditor and America’s simultaneous emergence as the largest net debtor has been “the source of considerable Japanese pride and sense of superiority toward the United States and the rest of the world.” See Edward J. Lincoln, Japan’s New Global Role (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1993), p. 59. |

U.S.-Japan alliance is a critical element in the overall environment facilitating a growing, positive Japanese role in international affairs.

For Japan the relative benefits of the alliance are arguably greater. Some analysts have recently contended that Japan is in the midst of a major shift in foreign policy orientation, from a preoccupation with the United States to a focus on Asia, partly due to the growth in economic and technological linkages.23 However, there are reasons to believe that a “turn toward Asia” that involves deemphasizing the U.S.-Japan alliance would not be a desirable long-term strategy for Japan. Even if Japan chooses to play a more active role in regional and global security affairs, the alliance with the United States will continue to serve as a substitute for an expensive indigenous military and military-industrial establishment. It is often pointed out that the alliance increases Japan’s flexibility in Asian diplomacy, prevents a large-scale arms race in the region aimed at Japan, and enhances Japanese economic access to the region. Recognition of Japan’s technological and industrial capability to field a formidable military force and doubts that Japan has come to terms with its past are underlying themes in relations with a number of Asian countries.24 There is also potential for heightened economic friction between Japan and its Asian neighbors.25 The possible consequences of a rupture in the U.S.-Japan security relationship—an isolated and rapidly rearming Japan setting off an Asian arms race and the formation of counter-strategies by countries in the region—would not be attractive to Japan or to other countries in Asia.

Beyond the baseline assumption that the alliance will continue for the foreseeable future, however, there is a range of possible directions that the relationship might take, each with different implications for cooperation in defense technology and for U.S.-Japan scientific and technological interactions more broadly. Domestic politics in both countries as well as the security environment in the Asia-Pacific region will affect the future course of the alliance. A number of concrete variables can be identified.

Defense Budgets

Barring a sudden shift for the worse in the global security environment, downward pressure on both U.S. and Japanese defense budgets is likely to continue. In Japan, for the past several years, this has meant essentially flat budgets, while in the United States it has involved significant cuts.26Still, U.S. defense spending will remain much greater than Japan’s.

|

23 |

Some analysts believe that Japan is increasingly central to an emerging hierarchical industrial structure in Asia, particularly in critical industries such as electronics. See Mitchell Bernard and John Ravenhill, “Beyond Flying Geese: Regionalization, Hierarchy and the Industrialization of East Asia,” World Politics, January 1995, pp. 171-209. The counterargument is presented by Edward M. Graham and Naoko T. Anzai, “The Myth of a De Facto Asian Economic Bloc: Japan’s Foreign Direct Investment in East Asia,” The Columbia Journal of World Business, Fall 1994, p. 6. |

|

24 |

This is illustrated by debates and uncertainties surrounding Japan ’s nuclear weapons capabilities and intentions. See Satoshi Isaka, “Going Nuclear Not an Option, Asserts Government,” The Nikkei Weekly, August 15, 1994, p. 4. |

|

25 |

In the economic sphere, for example, despite growing Japanese development assistance and direct investment in the region, access to the Japanese market continues to be an issue for Asian countries, as it is for the United States. Japan runs trade surpluses with most Asian countries, and its surplus with the Southeast Asian region grew from $20.6 billion in 1989 to $53.6 billion in 1993. See Ministry of Finance statistics compiled by Japan Economic Institute, JEI Report, No. 35A, September 16, 1994, p. 21. |

|

26 |

In the United States, Republican victories in the 1994 midterm elections imply that these cuts may be less severe than had been planned when the Democrats controlled Congress and the presidency. The defense budget debate will revolve around priorities and the amount of planned cuts that might be restored, not the overall trend, which is down. |

Obviously, defense spending patterns in both countries will have a significant impact on opportunities for technology cooperation, which is explored in detail elsewhere in this report. However, in the absence of the serious geostrategic threat represented by the Soviet Union, it is the judgement of the Defense Task Force that the time has passed when defense cooperation featuring primarily one-way transfers of technology from the United States to Japan could be justified by U.S. security interests in areas such as increased Japanese defense procurement. 27

Defense Capabilities

In a recent report to the prime minister, a Japanese private sector advisory committee endorsed exploring a number of new capabilities for Japan, such as reconnaissance satellites and other forms of intelligence capability, long-haul transport, in-air refueling, and theater missile defense.28 Given budget pressures, Japan is unlikely to acquire all of these capabilities in the near term and will be setting priorities. In the more detailed discussion below, we consider some of the factors likely to influence specific decisions.

What Sort of U.S.-Japan Security Alliance?

It is possible to conceive of a number of scenarios for the concrete substance of the U.S.-Japan alliance. Although it is possible that both countries will increasingly link their foreign policy initiatives to the United Nations or emerging regional fora such as the ASEAN Regional Forum, developments over the past several years illustrate the significant barriers that exist to building effective multilateral institutions. Alternatively, Japan might take a stance that, vis-à-vis its Asian neighbors, is more independent of the United States. Under this scenario, the U.S.-Japan alliance would be maintained largely because of the negative impacts associated with ending it rather than any positive commitment by the two countries to the joint pursuit of shared goals and values in world affairs. It is also possible that the United States and Japan will build the “global partnership ” aspects of the relationship, such as cooperation to help alleviate global environmental problems. Some opinion leaders in Japan have expressed the view that the most important future role for the U.S.-Japan alliance is as a foundation underlying Asian security, with some advocating expanded U.S.-Japan efforts to build multilateral dialogue and institutions.29 Recent discussions between U.S. and Japanese officials that have become known as the Nye or Lord-Nye initiative have been aimed at ensuring the long-term cohesion of the security alliance.30

|

27 |

The United States continues to have an interest in the composition of Japan’s defense budget and individual items, such as host-nation support. |

|

28 |

Advisory Group on Defense Issues, op. cit. |

|

29 |

The Institute for International Policy Studies and the Center for Naval Analyses, The Japan-U.S. Alliance and Security Regimes in East Asia, January 1995. |

|

30 |

See Joseph S. Nye, Jr, “Leadership and Alliances in East Asia,” speech before the Japan Society, New York, May 11, 1995. |

The Course of Economic Relations

Although the large and persistent trade and investment imbalances constitute the central feature of the overall U.S.-Japan relationship in the minds of most Americans, there is considerable disagreement in the United States over the causes, desirable remedies, or even the ultimate importance of these imbalances. Further, in contrast to security interests, which are defined and pursued by a few key agencies in each country and thus at least theoretically amenable to straightforward policymaking and implementation, economic interests are defined and pursued mainly in the private sector by millions of Americans in their roles as consumers and producers.

Still, since U.S. economic strength ultimately provides the foundation for national security, defining and pursuing economic interests should not pose a conflict with security interests in the long term. There is no reason for the United States to refrain from pursuing reciprocal access to markets and technology with Japan and other nations if this advances overall U.S. strategic interests. As discussed above, the “terms of trade” illustrated in Figure 2-1 have already shifted somewhat.

Managing the economic, security, and global partnership aspects of the U.S.-Japan relationship is likely to be challenging for both countries in the coming years. In particular, the long-term course of economic interactions and how both sides perceive the balance of mutual benefits will continue to have a significant impact on the overall atmosphere for cooperation. Leaders in both countries will continue to reevaluate the role of the alliance. Despite the challenges to effective management, however, the U.S.-Japan security alliance and other aspects of the overall relationship continue to serve the fundamental interests of Japan, and the United States continues to have leverage in the relationship as a result. For reasons that will be explored in the following chapters, however, exercising this leverage in defense technology relationships is by no means easy or straightforward.