2

Sanitary and Phytosanitary Risk Management in the Post-Uruguay Round Era: An Economic Perspective

DONNA ROBERTS1

Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, U.S. Trade Representative's Mission to the World Trade Organization, Geneva, Switzerland

Although many governments are now committed to reducing the number and rigidity of regulations that are thought to stifle economic innovation and competition, it is widely expected that the regulatory environment for agricultural producers and processors will become more complex in the coming years (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD], 1997). Income growth is fueling demand for environmental amenities and food safety, and increasingly regulators are being asked to provide these services when markets fail to do so. On the ''supply side" of regulatory activity, U.S. officials who devise sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures—regulations that sometimes restrict imports in order to reduce risks to animal, plant, and human health—face additional challenges. These officials are now bound by the multilateral legal obligations found in the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement; see Appendix A) of the World Trade Organization (WTO) which came into force in January 1995. Moreover, recent regulatory reform initiatives, including Executive Order (EO) 12866 and other Executive Branch directives, revise previous guidelines for

basing decisions about major regulations on assessments of their benefits and costs. Taken together, these developments have substantially changed the parameters for regulating imports of agricultural products from the time when "when in doubt, keep it out" was viewed as an appropriate decision rule.

It is clear that the domestic regulatory reform initiatives share many goals with the SPS Agreement. For example, both advocate transparency of regulatory rule making in order to promote symmetry of information among stakeholders, which include agricultural producers, processors, and consumers on one hand and trading partners on the other. Both also require that a regulation be based on a careful assessment of the risks that the measure is designed to mitigate and make provision for the inclusion of the costs of control programs as a factor in regulatory decisions.

However, in other respects, it is unclear whether the legal obligations found in the SPS Agreement are wholly congruent with U.S. Executive Branch guidelines for consideration of economic efficiency and distributional effects of measures as decision criteria. The SPS Agreement is primarily intended to aid WTO members in the decentralized policing of regulatory protectionism in foreign markets. Regulatory protectionism or capture occurs when domestic groups with a vested interest in a particular regulatory outcome successfully lobby for overly restrictive SPS measures that, by limiting or preventing safe imports, lower net social welfare. Two requirements in the SPS Agreement—to base SPS decisions on a risk assessment and to notify trading partners of changes in SPS measures—underpin the multilateral monitoring system. The risk assessment paradigm of the SPS Agreement, centered on the concept of "acceptable level of risk" (or "appropriate level of protection" in the language of the agreement), endorses risk-related costs as a normative basis for SPS regulatory decision making. This concept implicitly excludes consideration of benefits to other economic agents and generally fuses risk assessment with risk management by embedding value judgments about which risks are "acceptable" into scientific assessments. This approach stands in contrast to the economic paradigm of the Executive Branch directives in which normative rules for designing SPS measures rest on cost-benefit analysis tools to infer appropriate levels of protection from individual preferences.2

The simultaneous emergence of new multilateral and domestic rules for SPS regulatory decision making highlights the need for a comprehensive examination of this new regulatory environment. In this chapter I review the SPS Agreement with a view to examining how the agreement does or does not constrain the use of economic analysis in the design of regulations for imports

|

2 |

EO 12866 (1993) requires agencies to perform a cost-benefit analysis of all major regulations (those with an expected economic impact larger than $100 million). Directives published by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) clarify the general guidelines found in EO 12866. OMB's specific guidelines are found in Circular A-94 "Guidelines and Discount Rates for Benefit-Cost Analysis of Federal Programs." USDA guidelines are found in Appendix C of the Departmental Regulation on Regulatory Decisionmaking, DR 1512-1, "Guidelines for Preparing Risk Assessments and Preparing Cost-Benefit Analyses." |

that potentially pose biological and toxicological risks. In the first section of the chapter I examine the origins and principal provisions of the SPS Agreement. In the following section I provide a brief review of the use of cost-benefit analysis in regulatory decision making, which figures prominently in the Executive Branch initiatives. This review sets the stage for an assessment of the role of economic criteria in the multilateral rules for SPS measures. A close legal reading of the SPS Agreement is beyond the scope of this chapter and the expertise of this author. Rather, this review is intended to flag a number of potential issues and questions that could arise as the United States seeks to manage trade-related health and environmental risks more efficiently. The hope is that the answers to these questions can provide the basis for the design of an SPS regulatory template that gains international standing. In the final section I present some brief concluding remarks about the potential role for economics in risk management policies. This discussion notes that at this stage—in advance of extensive SPS jurisprudence and before many WTO members have acquired an understanding of their new international rights and obligations—the development of principles for efficient regulatory decision making could make a substantial contribution to the international trading system.

THE SPS AGREEMENT: ORIGIN AND PRINCIPAL PROVISIONS

Origin of the SPS Agreement

Prior to the conclusion of the 1986–1993 Uruguay Round of trade negotiations, multilateral disciplines on the use of SPS measures were found in the original General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) articles (primarily Article XX, General Exceptions( and the 1979 Tokyo Round Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (which was a plurilateral agreement known as the Standards Code). Although these legal instruments stipulated that measures could not be "applied in a manner which would constitute . . . a disguised restriction on international trade" or "create unnecessary obstacles to trade," the consensus view that emerged in the decade following the Tokyo Round was that multilateral rules had failed to stem disruptions of trade in agricultural products caused by proliferating technical restrictions (Roberts, 1998). Not one SPS measure was successfully challenged before a GATT dispute settlement panel after the Tokyo Round, and several prominent disagreements over SPS measures in the 1980s (most notably the U.S.-European Union beef dispute over hormone-treated beef) remained unresolved (Stanton, 1997). Meanwhile, the commitment to negotiate an Agriculture Agreement during the Uruguay Round, which would discipline the use of agricultural nontariff barriers for the first time, heightened concerns that governments would resort to regulatory compensation in the form of SPS barriers to appease domestic producers in this politically sensitive sector (Josling et al., 1996).

Consequently, the Punta del Este Ministerial Declaration, which launched the Uruguay Round in 1986, stated that one objective of the negotiations would

be to create disciplines that would minimize the "adverse effects that sanitary and phytosanitary regulations and barriers can have on trade in agriculture." Initial negotiations targeted perceived defects in the Standards Code, which had impeded resolution of some SPS disputes.3 But despite progress on closing some loopholes in early drafts of new Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) Agreement, support for the negotiation of a separate SPS Agreement emerged during the negotiations. Negotiators concluded that multilateral rules for adoption of risk-reducing trade measures, which routinely violate GATT Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) and National Treatment principles4 could not be conveniently incorporated into the new TBT Agreement. In 1988, a separate working party was created to draft an SPS Agreement. The working party, which included representatives from agricultural and trade ministries, as well as regulatory agencies, produced an agreement that established new substantive and procedural disciplines for SPS measures. The substantive requirements suggest a normative basis for SPS measures, whereas the procedural obligations facilitate decentralized policing of such measures.

Principal Provisions of the SPS Agreement

The SPS Agreement consists of a preamble that states the objectives of the agreement in broad terms, 14 articles that stipulate both procedural and substantive disciplines, and 3 annexes that set forth definitions and elaborate on procedural requirements (GATT, 1994). Articles 2 through 6, together with the definitions of SPS measure, risk assessment, and appropriate level of protection found in Annex A of the agreement, provide a basis for understanding what the principal multilateral rules for SPS measures are in the post-Uruguay-Round era.

The disciplines apply to regulations defined as SPS measures by the agreement: those measures that protect human, animal, or plant life and health within the territory of the member from risks related to diseases, pests, and disease-carrying or disease-causing organisms, as well as additives, contaminants, toxins, or disease-causing organisms in food, beverages, or feedstuffs. Two important points emerge from the definition. First, SPS

measures are defined with respect to the regulatory goal of a measure rather than the policy instrument itself (in contrast to other WTO disciplines for specific policy instruments such as tariffs). Thus, SPS measures span policy instruments of differing degrees of trade restrictiveness, from complete bans to information remedies (e.g., labels that list known allergens). Second, "plants and animals" in the definition include natural flora and fauna, and therefore SPS disciplines also apply to measures intended to protect unowned or commonly owned environmental assets. The agreement thus disciplines measures that protect both market and nonmarket goods.

The cornerstone of the SPS Agreement is Article 5 (Assessment of Risk and the Determination of the Appropriate Level of SPS Protection ). Article 5.1 contains the explicit requirement to base decisions about SPS measures on a risk assessment, which is defined as the evaluation of the likelihood and biological and economic consequences of identified hazards under different risk management protocols.5 Article 5.3 stipulates that countries are to consider direct risk-related costs (e.g., potential production or sales losses, administrative expenses, potential eradication costs) in risk management policies for plant and animal health. Members are also obligated to take into account the relative cost effectiveness of alternative approaches to limiting risks.6

Four other articles comprise the remaining substantive disciplines in the SPS Agreement. Article 2 (Basic Rights and Obligations) stipulates that measures must be "based on scientific principles," "not maintained without sufficient scientific evidence," and "applied only to the extent necessary." It also states that members must ensure that their measures do not arbitrarily or unjustifiably discriminate between members where identical or similar conditions prevail, which includes between their own territory and that of other members.7 Thus, if the commodity risk is thought to be the same for imports from country X and Y, the language of the agreement suggests that the importing country should adopt the same import measure for both countries. Article 6 (Adaptation to Regional Conditions, Including Pest-or Disease-Free Areas and Areas of Low Pest or Disease Prevalence) codifies the same modified MFN and National Treatment principles for subnational units that are free from diseases and pests or where the prevalence of diseases and pests are low. Article 3 (Harmonization) stipulates that, although members can adopt a measure to

provide a higher level of health or environmental protection than that provided by an existing international standard, scientific evidence must support that claim, and Article 4 (Equivalence) states that an importing country must accept a foreign measure that differs from its own as equivalent if the foreign measure provides the same level of health or environmental protection.

The phrase "appropriate level of protection" is threaded throughout the agreement, from the preamble to the annexes, clearly reinforcing the fact that the risk assessment paradigm was the point of reference for the SPS Agreement negotiators. For example, the agreement states that members may adopt measures that do not conform to international standards if these standards do not provide the level of SPS protection that a member determines to be appropriate (Article 3); that members shall accept the SPS measures of other members as equivalent if the exporting country objectively demonstrates that its measures achieve the importing country's appropriate level of SPS protection (Article 4); and that members shall avoid arbitrary or unjustifiable distinctions in appropriate levels of protection if such distinctions result in discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade (Article 5). A member's appropriate level of SPS protection is tautologically defined in the agreement as the level of protection deemed appropriate by the member establishing SPS measures to protect human, animal, or plant life or health. An explanatory note states that many members otherwise refer to this concept as the "acceptable level of risk."

There are some implications of adoption of a risk assessment paradigm. In this paradigm, analysts typically identify measures that are determined to mitigate risks to acceptably small levels. The risk management decision—in this case, the choice of an import measure or protocol—is restricted to consideration of the set of measures identified by analysts as achieving the risk target. The determination of the acceptable level of risk or appropriate level of protection encourages a myopic focus on only the direct risk-related costs of import protocols. The potential benefits of different regulatory options are only intermittently factored into decisions that regulators view as "unarbitrary and justifiable" distinctions in the appropriate level of protection. For example, it is not uncommon for regulators to accept imports of live breeding stock while rejecting meat because of "industry needs." The role of economics in the risk assessment paradigm is relegated primarily to the calculation of the quantity of imports to help risk assessors with their job of calculating the likelihood and consequences of disease or pest introduction, rather than to provide an explicit accounting of the costs and benefits of a policy's effects on producers, consumers, taxpayers, and industries that use the regulated product as an input.

COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS OF SPS REGULATIONS

U.S. Executive Branch directives related to improvement in the content and process for regulations over the past 25 years reflect policymakers' increasing interest in the use of cost-benefit analysis (CBA) as a tool for regulatory assessment. The intellectual foundations of CBA are found in welfare economics, which provides a theoretical framework within which policies can

be ranked on the basis of how much they improve social well-being. Social welfare is the yardstick used by economists to provide a single metric that captures the relevant features of well-being that might be affected by a policy. CBA can be described simply as a study to determine what effect proposed alternative policies would have on the value of this social welfare metric.8 Although acknowledging the empirical challenges associated with CBA, it is nonetheless advocated by many as a means for conveying some normative information to decisionmakers. 9 Its principal merits include transparency, a consistent framework for data collection and characterization of information gaps, and the ability to aggregate dissimilar effects into one measure (Kopp et al., 1997).

The metric employed in CBA is a monetary measure of the aggregate change in individual well-being resulting from a policy decision. In the economic paradigm, individual welfare is assumed to depend on the satisfaction of individual preferences, and monetary measures of welfare change are derived from the measurement of how much individuals are willing to pay or to be compensated to live in a world with the policy in force. Within this paradigm, a policy that improved social welfare as indicated by the metric would be preferred to a policy that would reduce welfare, and a policy that would increase welfare more would be preferred to a policy that would increase welfare less. Because a policy can (and indeed usually does) make some individuals better off while making other individuals worse off, the metric employed in CBA is net social welfare. The use of net social welfare to guide policy choices rests on the compensation principle—that a policy is preferred to the status quo if all those who benefit from the policy could in principle compensate those who lose, and still be better off than before the policy went into effect.

Net social welfare, or net benefits, produced by alternative SPS measures can be described most easily in the context of a single-commodity, partial equilibrium model to evaluate a proposed change in a plant or animal health measure. In this simple framework, SPS policy evaluation would entail the calculation of changes in the welfare of producers and consumers of the regulated product.10 For example, quarantine policy prohibits agricultural products from foreign sources unless the U.S. Department of Agriculture

(USDA) has specifically determined if and under what conditions a product may enter the United States. In this case, CBA-based decisions would require evaluation of whether the benefits of lower-priced imports (to consumers) would outweigh the potential costs (to producers) associated with these same imports. Producer losses would stem from two sources in this open-economy framework: lower product prices and the expected value of losses resulting from exotic pests or diseases.

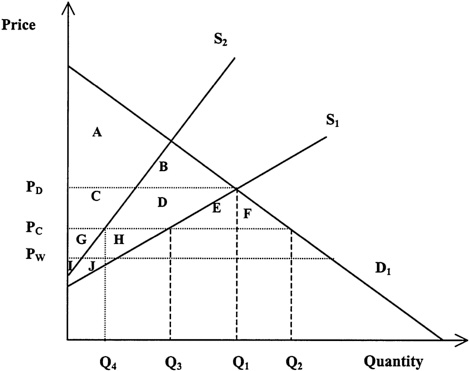

The net benefits of a proposed measure would be calculated from changes in producer and consumer surplus. Producer surplus is defined as producers' revenue beyond variable costs which provides a measure of returns to fixed investment. Consumer surplus is a measure of consumers' willingness to pay for a product beyond its actual price. Producer and consumer surplus can be seen in the context of the partial equilibrium model characterized in Figure 2-1. If the country did not import the product from any source prior to the import request received by the USDA, the price of the product in the domestic market (PD) would be determined by the intersection of the domestic supply and demand curves (respectively denoted S1 and D1). In autarky (when there is no trade), the quantity demanded and supplied in the domestic market is Q1. In this scenario, the area bounded by the demand curve and the price line is consumer surplus (areas A + B), and producer surplus is the area bounded by the supply curve and PD (C + D + G + H + I + J).

FIGURE 2-1. A Partial Equilibrium Model of the Welfare Effects of Alternative Import Protocols

Assume now that the USDA approves the import request, which allows imports of the product under a specified import protocol. These imports lower prices in the domestic market to PC, which is equal to the world price PW, plus compliance costs associated with the protocol. 11 (If the import request came from a country that produced the product at a higher compliance-cost inclusive price than the U.S. price, imports would not occur.) At PC, the quantity demanded by domestic consumers increases to Q2 while the quantity supplied domestically shrinks to Q3. (Imports equal to Q2 – Q3 make up the difference.) If scientists and regulatory officials judged that the probability of importing a disease along with the product was essentially zero—for example, if a disease had never been known to exist in the exporting country—producers would lose the area C + D, while consumers would gain the area C + D + E + F. The net benefits of this decision would be E + F. This "zero-risk" scenario is identical to the standard trade liberalization scenario wherein a country decides to eliminate a tariff.

However, evaluation of a change in an SPS measure to allow imports differs from the evaluation of removing a tariff if there is some probability, however small, that a disease will be imported along with the product. In addition to the producer and consumer surplus changes that result from a decrease in price in the domestic market from PD to PC, potential production losses from a disease must be evaluated as well. If pests raise production costs and lower yields with certainty, domestic supply will shift from S1 to S2, leading to a decline in domestic production to Q4 in Figure 2-1. Assuming trade is not embargoed, imports increase to Q2 – Q4. In this scenario, producers would lose C + D (the trade effect) as well as H + J (the disease effect), while consumers would gain C + D + E + F as before. In this simplified example, consumers are always better off, producers are always worse off, and the net benefit of this regulatory option is (E + F) minus (H + J), a difference that can be positive or negative. On a probabilistic basis, the expected domestic supply function will lie between S1 and S2 with its location depending on the assumed level of disease risk under the protocol. E + F is likely to be bigger than H + J in instances where there is a large price difference between the domestic and world price of a product, and the probability of introducing a relatively innocuous disease is negligible. H + J will be bigger than E + F in instances where there is little difference between the world and domestic price of a product, and the probability of importing an especially virulent disease is high. It is important to note that the choice among different risk mitigation alternatives will simultaneously determine the location

|

11 |

Two assumptions underpin the analysis presented in this discussion. First, it is assumed that the importing country is small in terms of the world market for the product, so its trade volume will not affect the world price. Hence, the excess supply curve faced by the importing country is perfectly elastic at PW. Second, Figure 2-1 reflects the assumption that the same regulation applies to all exporters and raises the price of the imported good by a fixed per unit amount, so that the compliance-cost inclusive price for the imported good can be characterized as PC. |

of S2 and PC, which complicates the evaluation of changes in producer and consumer surplus.

A decision rule based solely on CBA would imply that the decisionmaker would choose the import measure that would maximize the difference between E + F and H + J in this highly stylized example. Actual empirical estimates of the areas pictured in Figure 2-1 under different import protocols pose substantial challenges. The analyst must have a means for assessing the probability of introduction of a disease (a likelihood model) together with a means of assessing different disease outcomes (an epidemiological model) as inputs into the economic model to estimate (1) the expected value and standard errors of changes in producer surplus stemming from disease-related production and sales losses, (2) producer surplus losses resulting from lower prices, and (3) consumer gains from lower prices. Model results could then provide one input into the calculation of costs not pictured in Figure 2-1, including the administrative costs of the import protocol (if not covered by user fees) and the expected value of government disease eradication expenditures.

Earlier research on the costs and benefits of SPS measures typically overlooked the social welfare losses caused by restricting imports. For example, Aulaqi and Sundquist's CBA of the U.S. ban on imports from countries with foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) estimated the disease-related economic losses (a measure of the benefit of keeping the ban in place) and compared it to the public expenditures necessary to enforce the ban (a measure of the cost of the ban) (Paarlberg and Lee, 1998). Yet restrictive trade measures such as import bans impose welfare costs on society through higher prices, information that is omitted in studies that fail to account for the wider market effects of SPS policies.

How might a regulatory decision be altered by a full accounting of the costs and benefits resulting from a change in an import measure? By way of example, one could consider a recent study that calculated the costs and benefits of the USDA's 1996 rule which replaced an 80-year-old ban on imports of Mexican Hass avocados with a geographical and seasonal protocol (Orden and Romano, 1996). The new import protocol allows Mexican avocados to be exported to the Northeastern United States during winter months. In a long run model of the new measure, the estimates of net welfare increases ranged from $2.5 million to $55.7 million under different pest infestation scenarios.12 Had the ban been completely rather than partially rescinded, the estimates of net social benefits would have ranged from $32.4 million to $13.9 million under the same set of infestation assumptions. The primary difference between the alternatives is that, by completely rescinding the ban, consumers throughout the United States

would be able to purchase avocados at significantly lower prices year round, resulting in substantial increases in the benefits of this option relative to the alternative geographical and seasonal restrictions. If the decision rule were based solely on a CBA of the alternatives, the avocado ban would have been lifted altogether. 13

Another recent study of Australia's total ban on banana imports reinforces the same point—that in some instances the consumer (as well as processor and retailer) gains from removing a ban can far outweigh any loss to growers, even if diseases were to wipe out the industry (James and Anderson, 1998). In this sense, ''bad" phytosanitary policy can be "good" economic policy. The authors note that compensating producers out of consolidated revenue might be an affordable way to reduce opposition to changes in quarantine policies in these cases.

Although a single-commodity, partial equilibrium framework captures the direct costs and benefits for producers and consumers of a product (and is often the most feasible tool for analyzing specific regulatory proposals), it is important to recognize that there are always indirect economy-wide effects, and these can be larger than direct effects. Most importantly, any SPS restriction that increases the price of an imported good is, in effect, a tax on all exports. Raising the price of a tradable good bids resources away from other industries. Eliminating unnecessary SPS measures or improving the design of necessary measures to allow more imports allows trading nations to reallocate productive resources toward economic activities in which they have a comparative advantage. Modeling these global efficiency gains requires extending the analysis to include inputs, multiple commodities, and multiple countries in a general equilibrium framework.

IS THE SPS AGREEMENT CONGRUENT WITH EXECUTIVE BRANCH GUIDELINES?

From the previous discussion, what can be said about the apparent congruence or incongruence of the SPS agreement with recent U.S. Executive Branch directives? Examination of this issue is made somewhat difficult by the fact, that in aiming to avoid being overly prescriptive, both the SPS agreement and the CBA guidelines provide latitude for alternative interpretations.14 The

following discussion should be understood as only an attempt to flag potentially important issues for further discussion as the United States considers how best to incorporate CBA into its SPS decisions.

Disciplines that pertain to costs, benefits, and distributional effects of SPS measures are considered in turn. It is argued here that the language of the SPS Agreement, a product of the risk assessment paradigm, is clearest with respect to the risk-related costs associated with regulatory actions. How benefits of alternative regulatory options may factor into decisions is ambiguous, an ambiguity that slowed progress in fulfilling the mandate stipulated in the SPS Agreement to develop guidelines for measures to achieve the objective of providing a consistent "appropriate level of protection." Although distributional effects are not explicitly addressed in the agreement, it is not difficult to see how it does and does not circumscribe a regulator's ability to take distributional factors into account in risk management decisions.

Costs

Article 5.3 is reprised here to facilitate comparison of costs that are recognized by the SPS Agreement and costs as they are routinely calculated in a CBA. The article states

In assessing the risk to animal or plant life or health and determining the measure to be applied for achieving the appropriate level of sanitary or phytosanitary protection from such risk, Members shall take into account as relevant factors: the potential damage in terms of loss of production or sales in the event of the entry, establishment or spread of a cost or disease; the costs of control or eradication in the territory of the importing Member; and the relative cost-effectiveness of alternative approaches to limiting risks.

The cost components of a standard CBA were identified in the previous section as (1) the expected value of changes in producer surplus stemming from disease-related production and sales losses, (2) producer surplus losses resulting from lower prices, (3) government expenditures (if not covered by user fees) in administering the import protocol, and (4) the expected value of public-financed disease eradication expenditures.

With respect to the first item, the agreement seems to neither endorse or prohibit the translation of the expected value of revenue (production and sales) losses estimated during the course of a risk assessment into the expected value of producer surplus losses in a CBA framework. The agreement explicitly allows (and indeed uses the verb "shall" which indicates a legal obligation) the third and fourth components to factor into risk management decisions. Consideration of the second component would likely be seen to be in violation of the spirit of the SPS Agreement. The agreement is predicated on the idea that countries should not factor lower product prices resulting from imports into a

SPS decision. Such producer surplus costs would be regarded as costs related to commercial activity, unrelated to health or environmental protection.15

So far, the discussion of regulatory measures throughout this paper has centered on SPS measures that protect market goods. However, SPS measures include border measures that protect native flora and fauna as well. In many circumstances one measure will simultaneously protect herds as well as wildlife, because diseases can affect both—FMD, for example, affects both cattle and deer. For a complete accounting of the potential societal costs of a regulatory decision to allow imports that could introduce FMD into the importing country, one would ideally have to also estimate the value that the society placed on deer. Formally, an economist could estimate the recreational or nonuse value of an environmental good by means of stated preference techniques (e.g., contingent valuation methods) or revealed preference techniques (e.g., travel cost methods). Sometimes, however, the value of an unowned or commonly owned resource is (implicitly or explicitly) set by legislation (e.g., the Endangered Species Act). The SPS agreement says nothing about how protection of nonmarket environmental assets can or should be factored into risk management decisions.

Benefits

It is interesting to note that the word benefits (in reference to trade or anything else) does not appear in the agreement.16 One's interpretation of this omission is likely to depend on how one views the GATT and the WTO. One view is that the recognition of the benefits of trade liberalization is so universal that it merits no further emphasis. A less magnanimous view is that the trading system built around the GATT over the past 50 years is the product of enlightened mercantilism, rather than the ideology of free trade.17 Statements found in the agreement such as "sanitary measures shall not be applied in a manner which would constitute a disguised restriction on trade" (Article 2.3) or "Members shall insure that such (SPS) measures are not more trade-restrictive than required to achieve their appropriate level of sanitary or phytosanitary protection" (Article 5.6) are broad enough to accommodate both views.

In view of the lack of explicit disciplines on if and how the gains from trade can factor into SPS regulatory decisions, what conclusions can regulators draw? An example can best illustrate the agreement's ambiguity about the standing that benefits have in SPS regulatory decisions. Consider an example in which the USDA decides to allow imports of beef, but not poultry, because, although the expected value of disease-related losses are the same for the two products, the benefits to consumers of importing beef outweigh those costs whereas the benefits of importing poultry do not (i.e., relative to foreign competitors, the United States is a more efficient producer of poultry than of beef). Although the choice to allow only imports of beef might be efficient regulatory policy from a CBA perspective, some in the WTO community (and most certainly the country whose import request for poultry was turned down) would view these choices as evidence of "arbitrary and unjustifiable distinctions" in the levels of protection that had resulted in discrimination or a disguised restriction on trade, in violation of Article 5.5.

The omission of explicit disciplines on the consideration of benefits in the SPS agreement can perhaps be defended on the grounds that the agreement is an international trade treaty, not a regulatory blueprint. The purpose of the legal obligations in the agreement is to limit the use of the putative scientific claims for protectionist purposes, not to establish templates for risk management decisions. In short, the trade disciplines were not intended to be good practice standards.

But one might have hoped to see good practice standards emerge from the SPS Committee's efforts to develop guidance for Members to further the practical implementation of Article 5.5, as mandated by the Agreement. It has been clear in Committee debates, however, that many WTO Members hold the view that consumer/processor gains from trade fall in the same category as producer losses that result from decreases in domestic prices brought about by imports—as commercial considerations that might be appropriately factored into a country's choice of its single "appropriate level of protection," but which should not be used as decision criteria for individual risk mitigation measures. This view has stemmed from both philosophical objections as well as pragmatic concerns that CBA-based import protocols would complicate the effective decentralized policing of SPS measures by WTO Members. The Committee is scheduled to adopt a set of non-binding guidelines in June 2000, after struggling with its mandate over the past five years. It appears as though WTO endorsement of the use of economic criteria in risk management decisions will, for the present, remain restricted to the consideration of risk-related costs.

Distributional Issues

It would appear that many animal and plant health import measures in both developed and developing countries reflect the fact that regulators have historically placed greater (implicit) weight on producer rather than consumer welfare. Over time, the net costs of some extremely conservative import protocols have likely risen as technological advances in transport have

dramatically reduced economic distances. Executive Branch initiatives that include the requirement for the calculation of net social welfare for major regulatory actions can be viewed in the context of quarantine measures as an effort to prompt regulators to reexamine these implicit weights.

However, the directives reflecting the current mainstream view also state that, although net social benefits should be an important factor in regulatory decisions, it need not be the only one. For example, the USDA's Departmental Regulation on Regulatory Decisionmaking (DR-1512-1) encourages regulators to consider a broad range of qualitative factors such as equity, quality of life, and distributions of benefits and costs (USDA, 1996). These guidelines reflect societal concerns over a strictly utilitarian approach to policy making (e.g., adopting a policy that results in substantial benefits for the wealthy while impoverishing the poor).

Nothing in the SPS agreement precludes a member from maintaining extremely conservative import protocols to protect animal and plant health that favors producers over consumers, as long as there is some scientific basis for the measure. In fact, the agreement can be read as explicitly protecting the right of members to do so in the language regarding the choice of "appropriate levels of protection." According to the U.S. Statement of Administrative Action (SAA) to Congress, the agreement "explicitly affirms the rights of each government to choose its levels of protection including a 'zero risk' level if it so chooses" (President of the United States, 1994, p. 745). The SAA also notes that "In the end, the choice of the appropriate level of protection is a societal value judgment." Thus the agreement places no constraints on the USDA's choice of weights for producer and consumer welfare in a CBA framework as long as any variation in the weights does not appear to be connected to creating disguised restrictions on trade.

The use of other distributional effects as SPS decision criteria may be more limited by the agreement. For example, adopting more conservative protocols to provide a greater degree of sanitary protection for certain types of livestock because they are an important component of the income of poor farmers clearly runs counter to many basic SPS Agreement principles. However, potential conflict between the SPS Agreement and guidelines for consideration of distributional impacts in regulatory decisions is limited by the obvious fact that governments generally rely on other types of policies to remedy social ills.

The foregoing discussion highlights some issues that multidisciplinary teams will need to consider as U.S. agencies judge how best to incorporate CBA and other aspects of the Executive Branch directives into its regulatory decisionmaking process. One issue, the valuation of unowned resources, emerges within the risk assessment paradigm as well as the economic paradigm. Another, the issue of how policymakers should weigh the effects of a decision on producers and consumers, is implicit in the determination of the appropriate level of protection in the risk assessment paradigm and is explicit in the economic paradigm. Perhaps the most important issue is examination of the circumstances where using net benefits as a decision criterion (as recommended in the

economic paradigm) might run afoul of provisions of the agreement that hinge on comparisons of disease-related costs (the end product envisioned in the risk assessment paradigm).

CONCLUSIONS

Further study of individual SPS measures will provide evidence about the degree to which the SPS disciplines contribute to good economic policy. To date, debate over SPS measures has generally focused on the roles of national sovereignty; consumer concerns; and risk assessment in policy formulation, primarily reflecting legal, political, and scientific perspectives on risk management. The economic perspective on SPS regulatory decision making—that regulatory decisions should be informed by an analysis of the costs and benefits of the proposed regulatory options—has not been prominent in these policy discussions. Perhaps the conclusion to be drawn from discussions in the SPS Committee and elsewhere is that it is inaccurate to portray the SPS Agreement as a binding constraint that prevents regulators from using economic efficiency criteria as guideposts in making risk mitigation decisions. It would appear that such criteria have not systematically factored into SPS regulatory decisions in many WTO member countries, either before or after the Uruguay Round. It may therefore be more accurate to view the SPS Agreement as a mirror rather than a yoke for current approaches to risk management. But despite differences between what economists would recommend and what the agreement might allow or proscribe, the risk assessment paradigm of the SPS Agreement has clearly reduced the degrees of freedom for the disingenuous use of SPS measures to restrict imports in response to narrow interest group pressures. Because the past four years have been witness to a number of unilateral and negotiated decisions to ease SPS trade restrictions, the principles and mechanisms established by the agreement are credited with being an important institutional innovation that has, in some instances, counterbalanced regulatory protectionism or prodded regulatory inertia.

It is from this perspective that others will monitor how the United States will allow an integrated assessment of the costs and benefits of mitigation alternatives to factor into decisions about regulations that govern if and how agricultural products gain accesses to U.S. markets. Therefore, the challenge is to develop a framework in which mitigation alternatives can be ranked on the basis of efficiency and distributional goals with sufficient transparency to permit judgment about compliance with specific SPS agreement obligations that WTO trading partners now expect. A truly integrated assessment will involve coordination of multiple disciplines: entomologists and epidemiologists; agronomists, ecologists, and veterinarians; and political scientists, philosophers, and economists. It is likely that differences in paradigms, unstated assumptions, and expected end products of analysis will make such collaboration difficult at first. But the new regulatory environment for SPS regulators in the United States demands that such challenges be met. One hope is that the intragovernmental discussions about the use of CBA as a normative tool for public decision making

in the United States will help to clarify the international dialogue about criteria for the determination of levels of risk that are acceptable or appropriate.

REFERENCES

Evangelou, P., P. Kemere, and C. Miller. 1993. Potential economic impacts of an avocado weevil infestation in California. Unpublished paper, APHIS, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C.

Firko, M.J. 1995. Importation of Avocado Fruit (Persea americana) from Mexico: Supplemental Pest Risk Assessment. BATS, PPQ, APHIS, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C.

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). 1994. The Results of the Uruguay Round of Multilateral Trade Negotiations: The Legal Texts. Geneva: WTO.

James, S. and K. Anderson. 1998. On the need for more economic assessment of quarantine/SPS policies. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 42 (4):425–444.

Josling, T., S. Tangerman, and T.K. Warley. 1996. Agriculture in the GATT. London: Macmillan.

Kasperson, R. 1992. The Social Amplification of Risk: Progress in Developing an Integrative Framework. In Social Theories of Risk, S. Krimsky and D. Golding, eds. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger.

Kopp, R., A. Krupnick, and M. Toman. 1997. Cost-Benefit Analysis and Regulatory Reform: An Assessment of the Science and the Art. Discussion Paper 97-19. Washington, D.C: Resources for the Future.

Krugman, P. 1991. The move toward free trade zones. Economic Review, November/December:5–25.

Nyrop, J.P. 1995. A critique of the risk management analysis for importation of avocados from Mexico. Report prepared for the Florida Avocado and Lime Committee and presented at the public hearings on the avocado proposed rule, Washington D.C. and elsewhere, August.

Orden, D., and E. Romano. 1996. The avocado dispute and other technical barriers to agricultural trade under NAFTA. Paper presented at the conference NAFTA and Agriculture: Is the Experiment Working? San Antonio, Texas, November.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). 1997. Regulatory reform in the agro-food sector, in OECD Report on Regulatory Reform, Sectoral Studies, Vol. 1. Paris: OECD.

Paarlberg, P. and J. Lee. 1998. Import restrictions in the presence of a health risk: an illustration using FMD. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 80(1):175–183.

President of the United States. 1994. Message from the President of the United States Transmitting the Uruguay Round Trade Agreements to the Second Session of the 103rd Congress, Texts of Agreements Implementing Bill, Statement of Administrative Action and Required Supporting Statements, House Document 103–316, Vol. 1:742–763.

Raiffa, H. 1968. Decision Analysis: Introductory Lectures on Choice Under Uncertainty. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley.

Roberts, D. 1998. Preliminary assessment of the effects of the WTO agreement on sanitary and phytosanitary trade regulations. Journal of International Economic Law 1(3):377–405.

Stanton, G. 1997. Implications of the WTO agreement on sanitary and phytosanitary measures. In Understanding Technical Barriers to Agricultural Trade, D. Orden and D. Roberts, eds. St. Paul, Minn: International Agriculture Trade Research Consortium.

USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture). 1996. Guidelines for preparing risk assessments and preparing cost-benefit analyses, Appendix C, Departmental Regulation on Regulatory Decisionmaking, DR-1512-1. Available online at <http:/www.aphis.usda.gov/ppd/region/dr1512.html>>

WTO (World Trade Organization). 1998. EC Measures Concern Meat and Meat Products (Hormones), Complaint by the United States. Report of the Appellate Body, WT/DS48/AB/R. Geneva: WTO.