3

Peer-Review Practices at EPA

PURPOSES AND BENEFITS OF PEER REVIEW

PEER review is a widely used, time-honored practice in the scientific and engineering community for judging and potentially improving a scientific or technical plan, proposal, activity, program, or work product through documented critical evaluation by individuals or groups with relevant expertise who had no involvement in developing the object under review (see Lock 1985; Rennie 1990; Rennie and Flanagin 1994, 1998; NRC 1998b). Peer review seeks to assess and potentially to foster the improvement of scientific and technical methodology, evidence, criteria, assumptions, calculations, extrapolations, inferences, interpretations, and documentation.

When scientific and technical information is used as part of the basis for a public-policy decision, peer review can substantially enhance not only the quality but also the credibility of the scientific or technical basis for the decision. After-the-fact criticisms of the science are more difficult to sustain if it can be shown to have been properly and independently peer reviewed.

In addition to benefitting the end-products of scientific work, peer review of the plans or early stages of a technical effort can promote efficiency by helping to steer further work in productive directions.

Peer review is not monolithic. There are considerable differences

among the logic, social dynamics, procedures, and validity of various forms of peer review. For example, peer review of a prospective (planning) document is typically more tentative than review of a final work product. Similarly, peer reviews of broad programs are different from reviews of individual reports.

LIMITATIONS OF PEER REVIEW

Peer review is not quality assurance or quality control per se. It is essentially advisory, not controlling. Although it can be an important guide and aid to those responsible for ensuring quality, the essence of peer review is to criticize constructively, not to decide. Peer review relies on impartial, independent experts who might have expertise only on some portion of the scope of the work and typically have many other demands competing for their time. The experts performing reviews cannot be expected to be aware of all scientific areas, practical considerations, or constraints of the subject of review, nor should they be held responsible for the ultimate decisions beyond their own review comments. They cannot be held responsible for matters beyond their expertise or, ultimately, for the quality of a work product they did not produce. Those decisions should reside with the individuals and organizations responsible for the outcome. A decision-maker needs to know the views of qualified peers, but such peers often cannot be expected to integrate factors outside the document presented for review, such as the relevance, need, and priority of a new research activity or the role of research findings in a context that necessarily includes statutory requirements, economics, and many other considerations.

The value of the peer-review process in assessing and improving a scientific or technical work product depends on a strong commitment to conduct and apply the results of peer review appropriately in judging or improving the technical merit of the product. The benefits of peer review are diminished if the integrity of the peer-review process is compromised or if the criticisms and suggestions received from independent peer reviewers are to some degree ignored or taken lightly by decision-makers who may be more interested in meeting a deadline or producing a desired answer than in judging or enhancing technical merit.

Peer review is an expensive and personnel-intensive process. It re-

quires the services of many types of persons–skilled program officers and advisers, imaginative investigators, competent peer reviewers, and efficient grants-administration specialists. These individuals should work together in a constructive, trusting, and harmonious way to make the peer-review process effective and efficient. It is also very important that the limited supply of qualified peer reviewers be utilized efficiently. The cost of a peer review effort should be carefully considered in terms of in-house staff time and resources, as well as the limited time and energy of busy experts who must take time from other worthwhile endeavors.

Excessive application of peer review in some cases (e.g., laboratory program reviews) can be disruptive to a research organization and might diminish the sense of responsibility of laboratory managers to take appropriate measures on their own.

Peer review cannot substitute for technically competent work in the development of a product. It is not a foolproof remedy for poor work. Although peer review can be a valuable tool for improving a work product, it cannot be relied upon to ensure excellence in a product that is seriously lacking in technical merit when it enters peer review.

Peer reviewers are human and therefore can occasionally be narrow, parochial, biased, over-committed, or mistaken.

Peer review cannot ensure that regulatory policies and actions will be based on “good science.” It can only seek to assess and to aid in improving the technical merit and validity of the scientific and analytical information that is made available to government decision-makers. Peer review does not control what they do with that information. It is inevitable that much of the decision-making in any government agency is part of a process influenced by legislation, the courts, value judgments, ideology, politics, and efforts to accommodate stakeholders. Good scientific input to a decision cannot ensure that the decision will be based on good science if the science is ignored or outweighed by other considerations.

Peer review of original scientific articles submitted to journals has received some study in recent years, but there has been no rigorous study of the processes, benefits, and limitations of peer review of regulatory documents or the science that underlies them. Public debate about peer review in this context is often characterized by strong opinion, self-interest, and selected anecdotal evidence.

PEER-REVIEW POLICY DEVELOPMENTS AT EPA

Under the Federal Advisory Committee Act, the Environmental Research, Development, and Demonstration Act, and other statutes, several standing groups of highly qualified experts from outside EPA periodically review various scientific and technical practices, policies, and activities of the agency. These groups include EPA's Science Advisory Board (SAB) and its independently chartered subgroups, the Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee (CASAC), the Advisory Council on Clean Air Act Compliance Analysis (ACCAACA), and the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) Scientific Advisory Panel, as well as the Office of Research and Development (ORD) Board of Scientific Counselors (BOSC). These groups conduct their reviews and meetings in public and document their findings and recommendations extensively.

ORD, by virtue of its scientific staff and mission, has been familiar and comfortable with peer-review processes and has used them effectively for assessing and improving research publications and for various other purposes since the agency was created in 1970. Peer review has been a central feature of ORD's competitive research-grant program since that program was initiated in 1980, and ORD has had a formal peer-review policy in place since 1982 (40 CFR Part 40).

Some of the other offices of EPA have relied on scientific and technical information to various degrees, have substantial numbers of scientists on staff, and have utilized peer review in limited ways for many years. Prime examples are the Office of Prevention, Pesticides, and Toxic Substances; the Office of Air Quality Planning and Standards; and parts of the Office of Water. However, in some other parts of EPA, scientific activities and the use of peer review have not traditionally been prominent, and over the years, EPA has been criticized many times for having a poor scientific basis for many of its regulatory decisions (Powell 1999).

In 1991, EPA Administrator William Reilly requested a panel of four academic scientists, including two members subsequently appointed to our committee, to evaluate how EPA could meet the goal of using sound science as the foundation for agency decision-making. Their report, Safeguarding the Future: Credible Science, Credible Decisions (EPA 1992), reported that a perception existed that EPA lacked adequate safeguards to prevent the unacceptable practice of adjusting science to

fit policy. The panel recommended that an independent program of quality assurance and peer review be instituted and applied to the planning and results of all scientific and technical efforts to obtain data used for guidance and decision-making at EPA. This program would be applied not only to the research products of ORD, most of which were already being peer reviewed, but also to many activities and work products in the agency's regulatory program and regional offices, including model development and use, data collection and evaluation, monitoring plans, research, technical studies, scoping studies, and assessments. The panel considered such a program to be essential if EPA was to be perceived as a credible, unbiased source of environmental information.

In 1993, in response to those recommendations, Administrator William Reilly issued a policy memorandum that embraced the peer-review recommendations of the Safeguarding the Future report and promulgated an agency policy statement developed by EPA 's then-existing Council of Science Advisors (Reilly 1993). The policy strengthened and expanded the peer-review process in agency activities, but at the same time it specified that managers in the agency's programs should retain flexibility and discretion to apply peer review in the context of “program priorities and operating constraints.”

In his 1993 memorandum, Administrator Reilly noted that the process of peer review and other forms of peer involvement enable the agency to harness the knowledge of far more experts than those within the agency to improve the quality of its programs, documents, and decisions. He also noted that agency managers should maintain sufficient discretion to accommodate their program priorities and operating constraints, and he acknowledged a tension between peer review and the control of agency actions. He directed that major scientific and technical work products related to agency decisions should normally be peer reviewed, but that agency managers would continue to be accountable for decisions about when and how to utilize peer review. He noted specifically that peer review cannot be a substitute for required federal notice-and-comment requirements on rule-makings and adjudicative procedures. He requested the appointment of an agency working group to address implementation issues. Work products considered “non-major ” and non-technical were specifically excluded from the policy, but those items were not defined.

In February 1994, the General Accounting Office (GAO) issued a

report entitled Peer Review: EPA Needs Implementation Procedures and Additional Controls (GAO 1994) that found agency-wide peer-review practices to be deficient in several ways. It pointed out that the 1993 policy statement had not defined the technical products to be reviewed, and that implementation of the policy was being impeded by concerns among various EPA offices about the diversity of technical products and the scope, timing, cost, confidentiality, available expertise, and other aspects of reviews. The GAO reported a lack of consistent understanding, uniform procedures, and accountability mechanisms for peer review around the agency.

In June 1994, Administrator Carol Browner issued a peer-review policy statement that “reaffirmed the central role of peer review” in EPA (Browner 1994). The statement acknowledged concerns about the agency's lack of a comprehensive peer-review program, updated former-Administrator Reilly's 1993 statement on peer review, and articulated broad principles that remain in effect today. The 1994 statement designated EPA's Science Policy Council to coordinate the expansion and improvement of peer-review practices throughout the agency. It directed all EPA offices and regions to develop standard operating procedures for peer review and to work with the Science Policy Council in identifying “major scientific and technical work products” that should be required to undergo peer review. It described peer review as ranging broadly from informal consultations with previously uninvolved EPA staff colleagues (internal peer review) to external peer reviews by such groups as the EPA SAB or FIFRA Science Advisory Panel. While stating that major scientific and technical work products related to agency decisions “normally should be peer-reviewed,” the policy statement delegated to individual managers in the agency's headquarters offices, regions, laboratories, and field components the responsibility and accountability for deciding in individual circumstances whether to use peer review, and if so, deciding its “character, scope, and timing.” It cautioned that formal peer review should not be conducted in a manner that caused EPA to miss statutory or court deadlines.

In July 1994, an EPA agency-wide steering committee recommended strengthening the use of peer review throughout the agency (EPA 1994b), and in October 1994, EPA's ORD reported to Congress that it planned to work with the National Science Foundation to improve its peer review process for extramural grants and would expand the use

of peer review in other areas, including research plans, research contracts, cooperative agreements, interagency agreements, laboratory programs, intramural laboratory proposal competitions, research investigator performance, and research work products (EPA 1994c).

In March 1995, our committee expressed support for those actions of EPA and for ORD's stated plans to strengthen and expand its uses of peer review for both work products and plans (NRC 1995b). We recommended that an appropriate set of peer-review procedures be developed and applied with strong presumptions favoring peer review, the involvement of external experts, and the nomination of such experts by independent referees instead of project managers. We recommended that peer review be applied to intramural and extramural research projects and programs, including research conducted by EPA scientists and engineers at ORD laboratories and centers, as well as extramural research conducted by others (or cooperatively with others) through individual investigator grants, multidisciplinary grants, research centers, other cooperative agreements, interagency agreements, fellowships and training grants, on-site research support contracts, and other research contracts.

In September 1996, the GAO reported that EPA's implementation of its 2-year-old peer-review policy remained “uneven” (GAO 1996). The GAO acknowledged some improvements in peer-review practices, especially in ORD, but it attributed the spotty performance across other offices of the agency to misunderstanding of the nature, requirements, and benefits of peer review by many agency staff and managers, and also to inadequate mechanisms of oversight and accountability for peer review in EPA. The GAO selected and considered nine EPA scientific and technical documents that it judged to require peer review; and it concluded that EPA's peer-review policy had been fully followed for only two of them, not fully followed for five, and not conducted at all for two, including EPA's critically important Mobile Source Emissions Model, which was subsequently reviewed by the National Research Council (NRC 2000) at the request of Congress. The GAO observed that EPA's peer-review oversight mechanisms essentially consisted of a two-part reporting scheme in which each office and region annually self-nominated products for peer review and updated the status of previously nominated products. The GAO argued that agency managers were being given too much leeway to avoid conducting peer reviews without adequate, documented justification. It recommended

that managers be required to catalog all major scientific and technical work products, the plans for review of each, and the reasons why any of them were not chosen to be reviewed.

In response to the GAO report, EPA's deputy administrator asked the assistant administrator for research and development, in consultation with the other assistant administrators, to develop procedures for reviewing peer-review decisions and ensuring adequate peer reviews on all major scientific and technical documents throughout the agency (Hansen 1996). An agency-wide evaluation of peer-review implementation was initiated early in 1997. The evaluation was mainly conducted by ORD through case studies and interviews with cognizant managers and staff across the agency. It discovered a considerable variety of approaches, understandings, and attitudes around EPA with respect to peer review. Although it found some excellent examples of peer-review practices, it confirmed the GAO's finding of misunderstanding in various quarters and found that some offices were not considering all agency activities or the agency's regulatory agenda in identifying major products to be considered for review.

The problem was perhaps exemplified in the case of EPA's mathematical models. Many EPA rule-makings rely substantially on mathematical models that attempt to predict toxic risk, exposure, emissions, or other variables. It is important that the design, assumptions, and validation of such models be carefully peer reviewed. In response to concerns raised by the SAB in 1989 and a 1994 report of an agency task force on mathematical modeling for regulatory uses, ORD organized a “Models 2000” workshop, held in December 1997 in Athens, GA. At that workshop, many EPA staff members involved in developing and applying such models indicated that agency peer-review policies had not been followed and were not even widely understood.

In February 1998, Administrator Browner and Deputy Administrator Hansen issued a new peer-review handbook (EPA 1998a) to replace the standard operating procedures that had been developed by individual offices and regions in response to the administrator's June 1994 peer-review policy statement (Browner 1994). The new handbook, developed in an agency-wide effort under the leadership of EPA's Science Policy Council, was designed to provide uniform implementation guidance to managers and staff in the agency's offices, regions, and laboratories for peer review of the 2,000 major scientific and technical

work products per year estimated to require such review across the agency.

The handbook acknowledges that peer reviews at EPA take many different forms depending on the nature of the work product, statutory requirements, and office-specific policies and practices. In question-and-answer format with flowcharts and checklists, the new handbook provides guidance on basic principles and definitions, including distinctions between peer review and peer input, public comment, and stakeholder involvement; planning and preparing for peer review, including the identification of “major scientific and technical” work products, appropriate peer-review mechanisms, and qualified experts; and conducting peer reviews, including materials required, record-keeping, and the utilization of peer review comments.

It specified three categories of annual reporting from each EPA office and region: (a) a cumulative list of products reviewed since 1991 with a short summary of the review; (b) a list of candidate products for future review; and (c) a cumulative list of products for which a decision has been made not to review, with a brief description of the reasons for not reviewing it. The lists are to indicate the names of all decision-makers and dates of decisions concerning peer review.

The 1998 handbook reiterated that the agency's assistant administrators and regional administrators were responsible for peer reviews within their programs. It authorized these officials to delegate various responsibilities to subordinate managers and designated staff peer-review coordinators in each office and region. It assigned a special role to the assistant administrator for research and development to monitor and assist the other offices in ensuring adherence to the guidelines. The deputy administrator was identified as having ultimate responsibility for peer review across the agency and for arbitrating any conflicts or concerns about peer review.

In June 1999, Acting Deputy Administrator Peter Robertson instituted a new requirement that all action memoranda from EPA assistant administrators accompanying rule-makings submitted to the administrator for approval must include a statement certifying compliance with the agency's peer-review policies (Robertson 1999).

In November 1999, the Research Strategies Advisory Committee of the SAB reported that the agency has shown “diligence” with respect to peer review, that its peer-review process is “well-articulated,” “fun-

damentally sound,” and “with a few exceptions, working as intended” (EPASAB 1999). It concluded that EPA has been responsive to previous recommendations of the SAB, the GAO, and other organizations regarding peer review. It commented that EPA's peer-review processes are continuing to improve through high-level management commitment and a mechanism of continued internal examination and process changes led by the agency's ORD and Science Policy Council.

WHAT DOCUMENTS ARE PEER REVIEWED?

EPA's overall policy on peer review states (Reilly 1993; Browner 1994),

Major scientific and technically based work products related to Agency decisions normally should be peer reviewed. Agency managers within Headquarters, Regions, laboratories, and field components determine and are accountable for the decision whether to employ peer review in particular instances and, if so, its character, scope, and timing. These decisions are made in conformance with program goals and priorities, resource constraints, and statutory or court-ordered deadlines. For those work products that are intended to support the most important decisions or that have special importance in their own right, external peer review is the procedure of choice. Peer review is not restricted to the penultimate version of work products; in fact, peer review at the planning stage can often be extremely beneficial.

As discussed in the previous section, this policy led to the development of the Peer Review Handbook by EPA's Science Policy Council (EPA 1998a). Both the 1994 policy and the 1998 handbook concentrate on the peer review of “major scientific and technical work products” that affect agency decisions, although the 1994 policy also encouraged the review of certain planning documents.

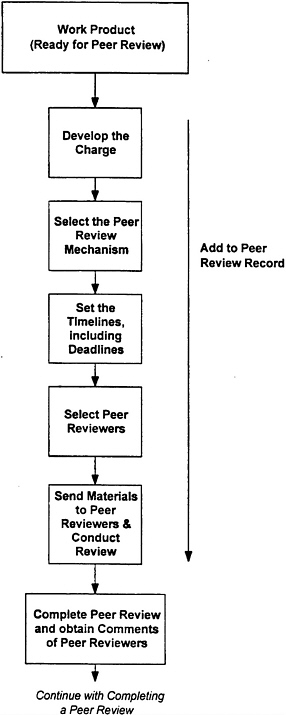

The peer-review handbook provides detailed guidance on deciding what documents should be peer reviewed (Figure 3-1). It specifies that peer review should be conducted on scientific and technical work products that support a research agenda, regulatory program, policy position, or other agency position or action. Such work products may

include risk assessments, technical studies and guidance, analytical methods, scientific database designs, technical models, technical protocols, statistical studies, technical background materials, technical guidance, and research plans and strategies. Examples of work products not to be reviewed are documents addressing procedural matters or policy statements. For work products supporting rule-making actions or site-specific regulatory decisions, the handbook specifies that the peer review should be performed on the scientific or technical document, not the rules, regulations, or decisions themselves. It specifies that scientific and technical work products supporting major rules, including rules determined to be “significant” by the Office of Management and Budget under Executive Order 12866, should be closely scrutinized.

In determining whether a scientific or technical work product warrants peer review, section 2.2.3 of the handbook allows case-by-case decisions to be made by agency officials but identifies several criteria for such judgments. These criteria include work products that significantly establish or depart from a precedent, model, or methodology; address novel, controversial, or emerging issues; have cross-agency or interagency implications; involve substantial resources; take innovative approaches; or satisfy statutory or other legal mandates for peer review. The handbook concludes overall that when there is doubt about whether to peer review a work product, the decision should be to make it a candidate for review.

Section 2.2.4 of the handbook includes certain categories of economics in its definition of work products needing review. They include guidance documents for conducting economic analysis; new economic methodologies; novel applications of economic methods; and broadscale economic assessments of regulatory programs. The handbook envisions that peer reviews of such work products will normally be conducted independently by the Environmental Economics Advisory Committee, a subgroup of EPA 's SAB.

Section 2.3 of the handbook exempts certain categories of work products from peer-review requirements, including derivative summaries or compendiums of previously peer-reviewed products or preliminary analyses subsequently replaced by peer-reviewed products. In addition, the handbook allows that in rare cases, statutory or court-ordered deadlines or financial constraints may limit or preclude peer review of major scientific or technical work products that would other-

wise be required to undergo review. Decision-makers are required to document justification for such decisions.

ORD has had a formal peer-review policy in place since 1982. As befitting a scientific organization, ORD utilizes peer review in many ways. Its current peer-review practices address not only the end-products of scientific work, but also research strategies and plans, research proposals, ongoing laboratory programs, research staff performance, fellowship applications, and other items.

Although the Research Strategies Advisory Committee (RSAC) of the SAB recently judged the agency's peer-review handbook to be “an excellent guidance document” that “provides definitive criteria for deciding what to peer review,” it expressed concern that the current mechanisms for deciding whether to peer review a particular product might in some cases be unduly influenced by available funding, timing constraints, and pressures to complete the product (EPASAB 1999).

On the basis of a review of EPA's lists of documents reviewed, chosen as candidates for future review, or considered but not chosen for review, the RSAC generally concluded that “the right products are being peer reviewed,” although it expressed uncertainty about whether some of the products classified as “not for peer review” should have been reviewed (EPASAB 1999). The RSAC cautioned that decisions to review or not to review a product are not always being documented consistently, and it stressed the importance of transparency in EPA's process of deciding the subjects and mechanisms of peer review.

The RSAC also recommended that the agency expand its peer-review practices beyond the “major scientific and technical work products ” specified in the 1994 peer-review policy statement and defined in the peer-review handbook (EPASAB 1999). In particular, the RSAC recommended that EPA also apply peer review

-

to interagency and international work products considered important to environmental decision-making;

-

not only to final work products but also to early review of significant scientific and technical planning products, such as strategic plans, analytical blueprints, research plans, and environmental-goals documents;

-

to social-science research and work products instead of only natural-science work products; and

-

to policy analysis documents that are not purely science-based

-

but involve the application of policy and values to ensure that appropriate methods and procedures have been used, including an explicit treatment of assumptions and value judgments, adequate sensitivity analysis, and adequate treatment of uncertainty.

The RSAC judged the omission of planning documents to be an important deficiency in the agency's peer-review handbook. It pointed out that peer review early in a project can have a significant impact on the direction of the effort and the quality of the final product. It observed that changes can often be made more easily in the planning stages of an activity than in the final-product stage, when there might be more resistance to change and greater deadline pressures.

Our committee generally concurs with the RSAC recommendations. Some of those recommendations already are being addressed to some extent in EPA's peer-review program. For example, Section 2.2.10 of the handbook specifies review of scientific and technical work products produced by organizations other than EPA when they are used in EPA decision-making. Also, the administrator's 1994 peer-review policy statement states, “Peer review is not restricted to the penultimate version of work products; in fact, peer review at the planning stage can often be extremely beneficial.” Section 2.2.1 of the 1998 handbook includes research plans and strategies among the work products requiring review, and ORD now does that routinely. Nevertheless, the other EPA offices have often failed to submit planning documents to peer review, and this NRC committee believes that greater emphasis in the agency's peer-review handbook on the categories of documents identified by the SAB could help improve the scientific and technical basis for agency actions.

FORMS AND MECHANISMS OF PEER REVIEW

Although Administrator Browner's 1994 peer-review policy statement directed that major scientific and technical work products related to agency decisions “normally should be peer-reviewed,” it delegated to individual managers in EPA headquarters offices, regions, laboratories, and field components the responsibility and accountability for deciding in individual cases whether to use peer review, and if so, de-

ciding its “character, scope, and timing.” It cautioned that formal peer review should not be conducted in a manner that caused EPA to miss statutory or court deadlines.

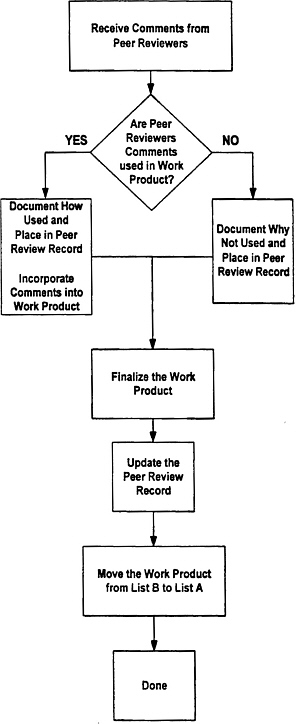

EPA's 1998 peer-review handbook provides detailed guidance on choosing the form and planning the conduct of peer reviews (Figure 3-2). It devotes considerable discussion to some issues that apparently had not been well understood in some parts of the agency. For example, it emphasizes that peer review is not “peer input,” sometimes called “peer consultation” – the involvement of experts, even outside experts, in the development of a work product – because adequate impartiality and detachment cannot be assumed for experts who participated in the creation of a document, even parts of it. It states that no amount of peer input can substitute for peer review by independent, third-party experts. It further stressed that peer review is not stakeholder input or consensus building; it is important to get the science correct before the values and policies are negotiated. It also distinguished peer review from public comment, such as that required by the Administrative Procedures Act or other statutes and obtained through the Federal Register or other means. It emphasized that peer review requires evaluation by individuals carefully chosen for relevant expertise and should focus on technical issues, whereas public comment is open to all individuals and all issues.

The handbook emphasizes that the greatest credibility is provided when peer reviewers are external to the agency and the peer-review process is formal. However, it acknowledges that peer reviews at EPA might take many forms and allows substantial flexibility in determining the forms and mechanisms of peer reviews, depending on the importance and complexity of a work product; the relevant statutory and judicial deadlines and other requirements; the financial resources; and the office-specific policies and practices.

Section 2.4.2 of the handbook provides examples of the kinds of external and internal peer review that may be conducted. External-review mechanisms may include reviews by individual outside experts; ad hoc groups of outside experts; agency-sponsored peer-review workshops; groups established under the Federal Advisory Committee Act, such as the SAB, FIFRA Science Advisory Panel, Clean Air Scientific Advisory Committee, or ORD Board of Scientific Counselors; special boards or commissions; interagency committees; committees convened by other agencies; or nongovernmental groups such as the National

Academy of Sciences or the Society of Risk Analysis. Internal-review mechanisms allowed by the handbook include reviews by experts from ORD or other offices of the agency or ad hoc panels of experts from the agency.

For scientific and technical work products supporting major rules, including rules determined to be “significant” by the Office of Management and Budget under Executive Order 12866, the handbook emphasizes that external peer review is the procedure of first choice, and any decision to use internal peer review for such work products, although acceptable in some circumstances, should be the exception rather than the rule.

While generally praising EPA's 1998 peer-review handbook and program, the RSAC of the SAB recently cautioned that the agency needs to ensure that the process does not become “inappropriately bureaucratic” (EPASAB 1999). It stressed the importance of keeping the focus of the peer-review process on the improvement and credibility of scientific products. It emphasized the need to avoid making peer-review requirements seem punitive or wasteful. ORD's BOSC reached a similar conclusion in its 1998 program review of the National Center for Environmental Research and Quality Assurance (EPABOSC 1998e). The BOSC expressed concern that peer-review and quality-assurance procedures in some cases might become or be seen by others as bureaucratic burdens that did not produce added value commensurate with their cost.

Our committee concurs with the above findings of the SAB and the BOSC. As discussed at the beginning of this chapter, peer review must be viewed and used as a tool for improving quality. It must become accepted as a part of the agency's culture, not merely a bureaucratic requirement. Steps should be taken to foster this cultural change (e.g., regular dissemination of the benefits of completed reviews).

The committee recommends that the Science Policy Council's reviews of the agency's peer-review handbook and experience with its implementation include an explicit focus on promoting appropriate forms and levels of review for different types of work products and on reducing unnecessarily complex or inefficient requirements. The Science Policy Council should not necessarily wait the 5-year interval specified in the peer-review handbook; it should make changes as needed. The agency cannot afford to allow unnecessary or inefficient

requirements to continue so long. The Science Policy Council's review should be ongoing. We also recommend that the Science Policy Council review a true random sample of peer-reviewed work products, examining the decisions made in structuring the review, the responses to review, and the cost, quality, timeliness, and impact of the review.

SELECTION OF PEER REVIEWERS

The 1998 peer-review handbook specifies that it is fundamental to the peer review process that reviewers be technically qualified – professional peers of the authors whose work is reviewed. The handbook also emphasizes that peer reviewers should be independent – not associated with the development of the work product, either through substantial contribution to its development or through significant consulration during its development.

Section 1.4.8 of the 1998 handbook specifies that peer reviewers are expected to perform their role with objectivity, as free as possible from institutional or ideological biases or financial conflicts of interest, although it notes that in many cases, some of these requirements might be impossible to meet or might not promote the best possible reviews. In such cases, the deliberate selection of some reviewers with offsetting biases can be appropriate and even necessary. Such cases should be fully disclosed. In many peer-review systems, reviewers are asked to maintain confidentiality to promote candor and to protect the authors whose work is being reviewed, but some peer reviews, such as those performed by EPA's SAB or other groups under the Federal Advisory Committee Act, are conducted openly.

Section 1.4.9 of the handbook allows EPA staff to be considered “independent” reviewers if such staff are in a different organizational unit of EPA and outside the chain of command of the responsible decision-maker.

In September 1999, EPA's Office of Inspector General issued a report stating that, in some cases, the management controls in place were insufficient to ensure that EPA program offices and contractors adequately screened peer reviewers for independence and potential conflict of interest (EPA 1999b). From a sample of 32 work products scheduled for review in 1997 or 1998, the report identified several cases in which EPA program offices or contractors had not attempted to de-

termine potential conflict of interests or had not properly documented their determinations. However, the report acknowledged that these instances might have occurred before the implementation of, or staff training on, the 1998 peer-review handbook. The Inspector General recommended that ORD supplement the handbook with additional guidance and training materials on the independence of peer reviewers, including any financial relationships with EPA, and ORD agreed to do so. The Inspector General also recommended that agency contracts should include specific provisions requiring contractors to address concerns about the independence of peer reviewers. The Inspector General also commented that some of the peer-review schedule information reported by program and regional offices to ORD was inaccurate. ORD responded that a new peer-review database, which became operational in July 1999, is expected to reduce such errors, and the SAB Research Strategies Advisory Committee recently commented that Section 3.4 of the 1998 peer-review handbook contains “good guidance on issues related to conflict of interest for the peer reviewers” (EPASAB 1999).

Our committee considers the most important resource required for a good peer-review program to be the availability of qualified expert reviewers who are willing and able to perform the reviews. The limits to this resource can be important. In its site visit to the ORD Extramural Center, members of our committee were informed that the review of STAR research grant applications alone requires the efforts of more than 1,000 peer reviewers per year, and EPA's Science Policy Council has estimated that over 2,000 major scientific and technical work products affecting agency actions currently require such review each year. That means EPA must identify and obtain the services of many thousands of expert reviewers annually. It is important to maximize the benefits from their efforts.

DOCUMENTATION AND RESPONSE TO PEER REVIEWS

EPA's 1998 peer-review handbook specifies that the completion of a peer review requires careful evaluation of reviewers' comments and recommendations, utilization of reviewers' comments to complete the final work product, and creation of a record of the review. The handbook provides guidance on each of these requirements (Figure 3-3).

The designated peer-review leader is responsible for assessing the validity and objectivity of all comments in consultation with other agency staff and, as appropriate, agency management. For each peer review conducted, the handbook requires the creation of a peer-review record that includes information such as the draft work product submitted for review; the charge and other materials given to the reviewers; the comments and other information received from the reviewers; materials prepared in response to the reviewers' comments, indicating acceptance or rebuttal and nonacceptance of the comments; the final work product revised in response to review; and other (e.g., logistical) information about the review.

The effectiveness of peer review in the improvement of a scientific or technical work product obviously depends not only upon the independent expert evaluations, but also upon what is done in response to those evaluations. If the criticisms and suggestions received from independent peer reviewers are to some degree ignored or taken lightly by decision-makers who might be more concerned about meeting a deadline or producing a desired answer than enhancing technical merit, then the benefits of peer review are compromised. On the other hand, in most types of peer reviews, there is no requirement for a consensus among the reviewers. In fact, there is no requirement to accommodate all reviewers ' comments. Reviewers can be mistaken. But the integrity and value of the peer-review process depends critically on thoughtful and conscientious consideration and application of the comments.

MANAGEMENT AND OVERSIGHT OF PEER REVIEWS

In 1996, the GAO observed that EPA's peer-review oversight mechanisms essentially consisted of a two-part reporting scheme in which each office and region annually self-nominated products for peer review and updated the status of previously nominated products (GAO 1996). The GAO argued that agency managers were being given too much leeway to avoid conducting peer reviews without having to justify the decisions. It recommended that managers be required to catalog all major scientific and technical work products, the plans for review of each, and the reasons why any of them were not to be reviewed.

In response, EPA's deputy administrator initiated an ongoing “audit” that was assigned to the Quality Assurance Division of ORD's National Center for Environmental Research and Quality Assurance to evaluate on an ongoing basis the extent to which the agency's offices and regions were complying with the administrator's 1994 peer-review policy. The agency's 1998 peer-review handbook reinforced this ongoing evaluation by requiring that decisions on whether to peer-review any scientific or technical work product be documented through the agency's annual peer-review reporting process. As specified in Section 1.3.2 of the handbook, three lists are maintained: (a) a cumulative list of work products peer reviewed since 1991, (b) a list of candidate products for future peer review, and (c) a list of products for which a decision has been made not to undergo peer review. The lists contain information on each work product, such as the responsible EPA office or region, peer-review leader, agency decision-maker, review mechanism, review dates or schedule, a summary of the review, and comments on the review process or a rationale for not conducting a peer review. The handbook specifies that the designated peer-review coordinator for each EPA office or region is responsible for organizing an annual review of all peer review activities in that office or region and providing it to ORD according to annual guidance issued by the EPA deputy administrator.

Pursuant to the EPA administrator's 1994 peer-review policy statement, the agency's Science Policy Council is responsible for overseeing agency-wide implementation of the policy. This oversight includes an ongoing responsibility to interpret the policy, assess its implementation, and revise the policy as necessary. The Science Policy Council has established a peer-review advisory group to assist it in carrying out these responsibilities.

Section 1.4 of the 1998 handbook specifies that the assistant administrator or regional administrator in charge of an EPA office or region is ultimately accountable for implementing the peer-review policy in his or her respective organizations, and that the EPA deputy administrator is ultimately responsible for peer review across the agency, including final arbitration of any conflicts or concerns about peer review. Section 1.4 also defines the roles of “decision-makers,” “peer-review coordinators,” and “peer-review leaders.” Although the assistant administrator or regional administrator is the ultimate decision-maker for each peer

review, the handbook allows this role to be delegated to subordinate office directors, division directors, or even project managers. The decision-maker is responsible for determining whether a work product gets reviewed, determining what peer-review mechanism to use, ensuring the necessary time and resources for the review, and ensuring the proper performance and documentation of the review or decision not to review a work product. The peer-review coordinator is the staff member responsible for monitoring and overseeing all peer-review activities within a given EPA office or region, coordinating peer-review training, mediating difficult issues, ensuring proper record-keeping on peer reviews, and functioning as the office or regional peer-review liaison with ORD and the Science Policy Council. For each peer review (i.e., the review of each work product), the decision-maker designates a peer-review leader. Section 1.4.4 of the handbook allows the decision-maker or the project manager for a work product to be the peer-review leader. The peer-review leader is responsible for organizing, overseeing, and documenting the individual review, including selecting and instructing the peer reviewers and responding to the reviews. Either directly or through an agent such as the SAB or a contractor, the peer-review leader is to select peer reviewers with appropriate expertise and independence, as specified in Section 1.4.8 of the peer-review handbook, and write an appropriate charge to the reviewers, including information on the purpose of the material to be reviewed, its potential use in agency decision-making, and the key scientific and technical findings and issues. The peer-review leader or agent should be trained in peer-review practices and should understand the scientific content and issues in the material to be reviewed.

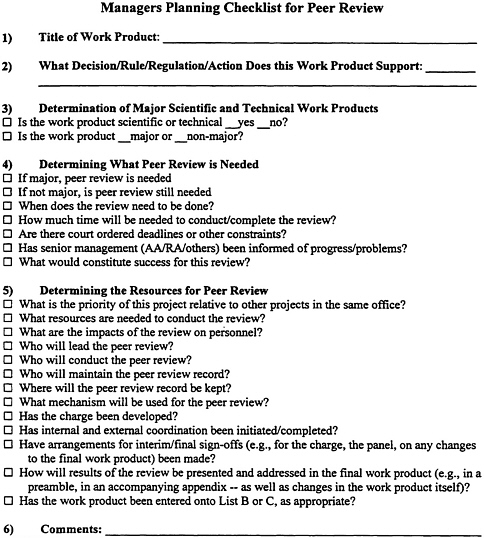

The 1998 peer-review handbook also emphasized the importance of proper planning for peer review, stating that peer review “needs to be incorporated into the up-front planning of any action based on the work product – this includes obtaining the proper resource commitments (people and money) and establishing realistic schedules.” It recognized that peer review unavoidably adds to the time and cost of a project and should be realistically planned into the project. The handbook provided a “manager's planning checklist” for this purpose (Figure 3-4).

In 1999, the SAB began a multiyear effort to assess the peer-review program in EPA. In the first report resulting from this effort, the SAB

FIGURE 3-4 Managers planning checklist for peer review. Source: EPA 1998a.

praised “the Agency's diligence” and high-level management commitment to peer review” (EPASAB 1999). It judged EPA's peer-review process to be “well established” and that it “is well articulated and appears to be fundamentally sound and, witha few exceptions, working as intended.” It noted that EPA's peer-review program is “continuing

to improve through a mechanism of continued internal examination, led by the Office of Research and Development and . . . the Science Policy Council.” The SAB emphasized that a key to success in implementing the peer-review process has been the involvement of ORD in the oversight role, and that “ORD scientists have an understanding of the importance of peer review in developing good scientific and technical products. ” The SAB noted favorably ORD's effective role in the development and implementation of peer-review training, collection of data on products and their review status, and bench-marking of EPA's peer review efforts against reviews at other organizations. The SAB plans to continue conducting an in-depth assessment of trends in EPA's uses of peer review, the impacts of the peer reviews, and additional opportunities for enhancing the benefits from peer review in the form of quality, credibility, relevance, and the agency's leadership position.

The SAB expressed concern about potential conflict of interest on the part of designated peer-review leaders, noting that current agency policy, as stated in Section 1.4.4 of the peer-review handbook, allows an agency decision-maker on a particular work product to be the peer-review leader (EPASAB 1999). Such a manager might have a special interest in the outcome of the review and might therefore be unable to ensure the essential degree of independence of a peer review. The SAB compared this policy to the agency's data-quality-assurance practices, in which a quality-assurance staff officer is empowered to stop activity if there is a quality-assurance problem. It recommended that peer-review leaders be similarly empowered to stop a work product from moving forward if a peer review has not been properly completed. In addition, it recommended that agency staff be required to complete appropriate training before being designated as a peer-review leader.

EPA has made excellent progress in expanding and strengthening its peer-review practices, and in most respects, EPA's 1998 peer-review handbook is consistent with the recommendations of a previous NRC report (NRC 1998b). However, our committee concludes that the agency should find a way to ensure a greater degree of independence in the management of its peer reviews. The committee acknowledges that it is appropriate for the agency's peer-review policies and handbook to afford flexibility to accommodate statutory and court deadlines and resource limitations, and this committee does not disagree with EPA's policy of holding the assistant administrators, regional administrators,

and subordinate managers in the agency's regulatory programs accountable for peer review. Nevertheless, independence is essential to the proper functioning of the peer-review process, and EPA's current policies fail to ensure adequate independence. Our committee shares the SAB's concern about the potential conflicts of interest of EPA peer-review leaders and decision-makers.

Therefore, our committee recommends that EPA change its peer-review practices to more strictly separate the management of a work product from the management of the peer review of that work product. The committee believes that the decision-maker and peer-review leader for a work product should never be the same person, and that wherever practicable, the peer-review leader should not report to the same organizational unit as the decision-maker. Although the decision-maker should retain the authority to overrule provisionally any decisions or objections from a peer-review leader, with the final decision to be made by the EPA administrator, the independent decisions and any objections of a peer-review leader should be preserved and made a part of the agency decision package and public record for a work product. If such an independent assessment produces criticism of the adequacy or outcome of a peer review, EPA's policy should be to ensure that such criticism is clearly noted, divulged, and explained.

For completed research work products, our committee encourages ORD to continue and to expand its longstanding practice of urging the in-house and extramural research scientists it supports to publish their research in peer-reviewed journals that meet international standards of scientific quality. To the extent possible, intramural and extramural research supported by EPA should be published in peer-reviewed journals that are open to scientific and public scrutiny. When such publication is not possible (e.g., when the volume of the research results that are important to the agency is so large that the pertinent results cannot be accommodated in a peer-reviewed journal), panels of experts should make an evaluation of quality that is essentially equivalent to that of the peer-reviewed scientific literature. Evaluations should include scientists and engineers from outside ORD and also outside EPA.