4

Crisis Response and Outreach

WHAT IS VOLCANO CRISIS RESPONSE AND WHY SHOULD THE VHP DO IT?

The third operational component of the VHP mission, after assessment and monitoring, is crisis response. The transition from monitored volcanic activity to a volcanic crisis has as much to do with potential societal impact as with the nature of the eruptive phenomena. For example, mitigation of the nearly 20-year eruption of Kilauea volcano that began in 1983 passed back and forth between routine monitoring, when no human infrastructure was immediately threatened, to crisis response, when subdivisions and highways lay in the path of advancing lava flows. Similarly, the Mammoth Lakes resort area of eastern California had a serious volcanic crisis in the early 1980s triggered by a large number of earthquakes, even though no magma broke the surface. In contrast to research, assessment, and monitoring, which all can be carried out largely by scientists and technicians with minimal involvement of the general public, crisis response requires close coordination with civil defense officials and the potentially affected population. Consequently, this aspect of the VHP requires the integration of a broader set of political and social science skills than an organization of geoscientists would normally be expected to possess.

In the United States, the USGS is expressly and uniquely empowered by the Stafford Act (Public Law 93–288) to issue timely warning of potential volcanic disasters to affected communities and civil authorities. Warnings can lead emergency management officials to evacuate people and property from areas of high hazard and can help educate the public about the possible impacts of impending eruptions. The VHP maintains the capability and protocols for rapidly deploying response-ready staff and monitoring equipment. Since 1980, the program has provided major response to 10 domestic volcano-related emergencies: Augustine, Redoubt, Spurr, Akutan, and Pavlov volcanoes in Alaska; Long Valley in

California; Kilauea, Mauna Loa, and Loihi in Hawaii; and Mount St. Helens in Washington (Figure 1.1).

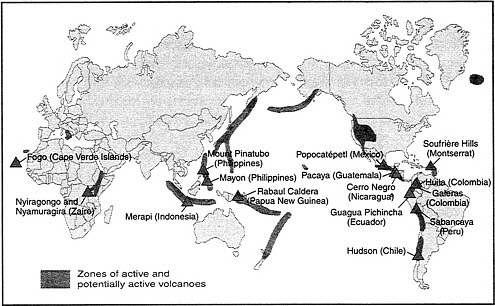

Although not an explicitly mandated part of its mission, the VHP has also developed an international crisis response capability, the Volcano Disaster Assistance Program. Following the disastrous eruption of Nevado del Ruiz, Colombia, in 1985, which killed more than 23,000 people, the USGS and the U.S. Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) developed VDAP, headquartered at CVO, to respond to select volcanic crises around the world. VDAP has proven to be highly effective in saving lives and property by assisting local scientists in determining the nature and possible consequences of volcanic unrest and communicating eruption forecasts and hazard mitigation information to local authorities. VDAP has responded to 15 international volcanic crises since 1980 (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 Map showing volcanoes to which VDAP has been deployed since the program was formed in 1986. Graphic designed by Sara Boore and Susan Mayfield.

VDAP offers direct and indirect benefits to the VHP and the U.S. government. Foreign responses provide valuable training for scientists from both the USGS and the affected country. Foreign responses also offer the VHP a statesmanship role and allow for the development of expertise and institutional capabilities in other countries so that they can better deal with subsequent crises both in the United States and abroad. They allow more frequent testing of equipment and techniques, eruption models, and process theories than would be possible solely from domestic responses. VDAP also helps further the global interests of the U.S. government by protecting U.S. businesses and military installations in foreign countries where large volcanic eruptions occur. With the growing globalization of the economy, damage to U.S. companies and industries from natural disasters in any part of the world can have both immediate and long-term impacts on domestic economic security.

WHAT IS THE STATUS OF CRISIS RESPONSE WITHIN THE VHP?

A successful volcano crisis response is built on information gathered during process-oriented research, hazard assessments, and monitoring campaigns. Fundamental research helps refine eruption models so that they can be applied more accurately to real situations. Prior hazard assessments provide essential clues about the possible impacts of future eruptions. A comparison with baseline monitoring data collected over years or decades gives the response team clues about the rate of development of the crisis.

Once unrest has been detected, a much more extensive instrumentation suite may be deployed on and around the volcano, and more personnel can be brought in to assist with data interpretation. If significant danger is thought to exist, a team of scientists from both inside and outside the VHP is assembled. It is essential that this group be able to work collaboratively, under increased public scrutiny, for long hours, and under intense pressure. It must be able to evaluate and update existing emergency response plans and to communicate them effectively to civil defense officials and the media.

Each VHP observatory has its own crisis response needs and protocols. At HVO, the eruption that began on Kilauea’s east rift zone in 1983 continues unabated to this day; and this has led to an ongoing

atmosphere of alert, sometimes punctuated by true crisis, that has strained the observatory’s human and instrumental resources. The future response of HVO to this eruption might well be reassessed so that staff members could be freed for other tasks. AVO’s responses are directed chiefly at the needs of the aviation community: rapid and accurate confirmation of the existence of ash plumes followed by up-to-date trajectory information. CVO has not had to deal with a local crisis since the end of the eruption of Mount St. Helens nearly 15 years ago, although CVO scientists have responded to crises elsewhere, including Long Valley.

When the VHP is asked to respond to an international crisis, it uses a systematic approach. At the request of host countries and in conjunction with the USAID, an experienced team of USGS and other scientists can be dispatched rapidly to developing volcanic crises with a portable cache of state-of-the-art monitoring equipment. In contrast to domestic crisis response, foreign deployments generally build upon monitoring and assessment efforts carried out by agencies of other governments following protocols that may be significantly different from those used by the USGS.

The USGS contribution to VDAP includes two seismologists, several engineers and technicians, administrative and outreach specialists, links to the academic community, and access to volcanologic expertise throughout the agency. The USAID provides half-time salary support for seven core scientists, a full-time geoscience adviser to the OFDA, and an emergency fund that covers rapid response, technical assistance visits, collaborative scientific work, training for staff in developing countries, an equipment cache, and development funds. Other beneficiaries of VDAP, such as the overseas offices of U.S. corporations or the U.S. military, make very limited or no financial contributions to sustaining the program.

The committee heard widespread praise for the scientific quality and commitment of the VDAP team. This group has a proven track record of directly and sensitively assisting many countries. Perhaps best documented is the response to the eruption of Mount Pinatubo, Philippines (see Sidebar 4.1), during which accurate prediction of the timing and magnitude of the explosive phase led to great savings of lives and property. The VDAP response left the PHIVOLCS better able to deal with future volcanic crises.

|

SIDEBAR 4.1 On April 2, 1991, after being dormant for 500 years, Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines awoke with a series of steam explosions and earthquakes. About 1,000,000 people lived in the region around the volcano, including about 20,000 American military personnel and their dependents at the two largest U.S. military bases in the Philippines: Clark Air Base and Subic Bay Naval Station. The slopes of the volcano and the adjacent hills and valleys were home to thousands of villagers. VDAP responded immediately by joining the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology and installing monitoring instruments and interpreting deposits from previous eruptions. On the morning of June 15, 1991, Pinatubo experienced the largest volcanic eruption on earth in more than 75 years. The most powerful phase of this eruption lasted more than 10 hours, creating a cloud of volcanic ash that rose as high as 35 km and grew to a diameter of nearly 500 km. Falling ash covered an area of thousands of square kilometers, and pyroclastic flows filled valleys with deposits of ash as much as 200 meters thick. Estimates show that the monitoring performed by the USGS and PHIVOLCS saved at least 5,000 lives. The alerts allowed residents living around Pinatubo to flee to safety. It also permitted more than 15,000 American military personnel and their families to evacuate Clark Air Base for safe locations. In addition, property worth hundreds of millions of dollars was protected from damage or destruction in the eruption. Aircraft and other equipment at the U.S. bases were flown to safe areas or covered, and losses of at least $200 million to $275 million were avoided. Philippine and other commercial airlines prevented at least another $50 million to 100 million in damage to aircraft by taking similar actions. Other commercial savings and the sentimental or monetary value of the personal property salvaged by families are difficult to quantify but nonetheless important. These savings in lives and property were the result of quick response and monitoring of Mount Pinatubo by scientists in PHIVOLCS and VDAP. |

WHAT ARE THE OBSTACLES TO SUCCESSFUL CRISIS RESPONSE BY THE VHP?

Although crisis response is clearly one of the most successful aspects of the Volcano Hazards Program, the committee heard several suggestions for ways in which these functions could be improved. These ideas, which parallel proposals raised in Chapters 2 and 3, fall under the

headings of training and knowledge dissemination, infrastructure and budget, and partnerships. Here the committee highlights some of these potential problem areas and makes recommendations for their solution. Additional suggestions can be found in Chapter 5.

Training and Knowledge Dissemination

Often the most valuable asset for a scientist responding to a crisis is relevant prior experience. Because its members are exposed to a wide variety of eruption styles and settings, VDAP offers the most effective way to prepare VHP staff for future domestic crises. The present system for selecting non-VDAP members of the VHP to join its foreign deployments appears too haphazard. The VHP should implement a more formal mechanism for participation in VDAP to see that as many people as possible are exposed to this type of training. Inservice workshops provided to staff members at VHP observatories by VDAP personnel would be another way to disseminate the knowledge gained at foreign volcanoes. These workshops, by allowing a number of staff members from various observatories to discuss crisis situations, provide good opportunities for team building prior to the onset of an actual eruptive crisis to which they must respond.

Another missed opportunity for expanding the training potential of foreign volcanic crisis responses comes from the inability of VDAP members to archive their observations. In the high-stress environment of a volcanic eruption, scientists and technicians rarely have the time to provide good documentation (to national standards where they exist), archiving, and open access to their data. Yet these data could be used for background studies in preparation for dealing with new unrest elsewhere in the world. A possible solution would be to create one or more documentation and archive specialist positions for each response team, somewhat like the journalists assigned to military units during wartime. The success of VDAP should be measured not only in terms of mitigation of eruption impact, but also in terms of how well information and knowledge are disseminated in anticipation of future crises. This change of strategy might ensure greater access to data that could be used to prepare future crisis teams.

A related programmatic issue is how staff members balance their responsibilities. Even if assistance were provided for archiving and

distributing data from volcanic crises, individual scientists still have to incorporate their experiences into the published scientific literature. There is no question that the VHP and USGS benefit from the firsthand, frontline knowledge gained by VDAP workers in crisis situations. However, timely publication of the results enhances the flow of information that eventually leads to better understanding, improved forecasting, and crisis response. In addition, by publishing their observations, techniques, and conclusions, the scientific staffs maintain their stature and credibility. This issue demands close monitoring, coordination, and allocation of staff time by the relevant scientists in charge to ensure that such information is forthcoming. The stated VHP goal of carefully documenting actual volcanic crises and responses is extremely important if the maximum information is to be obtained from any given eruption and is strongly endorsed by the committee.

Infrastructure and Budget

In addition to the valuable staff training opportunities provided by VDAP missions, foreign responses also allow new hardware and software to be evaluated under crisis conditions. Technical development of new instrumentation requires field tests for accurate calibration. Domestic volcanic crises are generally too infrequent (Cascades), too inaccessible (Alaska), or too limited in scope and applicability (Hawaii) to permit adequate assessment of a broad range of equipment needed during a serious eruption. In contrast, foreign volcanic activity occurs in a wide variety of geologic, climatic, and sociopolitical settings, allowing for much more rapid calibration and improvement of new instruments.

A consequence of continuing tight VHP budgets has been the growing obsolescence of much of the equipment used in crisis response. One way the VHP can extend its equipment budget is to partner with manufacturers and other government agencies that design new instruments. In the 1970s and 1980s, the national laboratories of the Department of Energy had programs to develop new techniques for monitoring volcanoes. In the past decade, NASA has supported a working group focused on finding better ways to monitor active volcanoes using remote sensing. The Department of Defense is actively involved in the development of microelectronic sensors of various types that can operate in extreme conditions such as volcanic craters, flows and

plumes. Coordination between the VHP and programs such as these could help stretch the limited funds available for crisis response while expanding the range of information obtainable from dangerous volcanoes. The committee encourages the VHP and VDAP to work more closely with NASA, DOE, DOD, and NOAA, as well as with NSF-funded consortia like University NAVSTAR Consortium (UNAVCO) and Incorporated Research Institutions for Seismology (IRIS), in the development of new instrumentation and approaches suitable for detecting the conditions within erupting volcanoes. However, the testing of new instruments and methods should never compromise VDAP’s ability to effectively respond to a volcanic crisis.

The current level of VDAP funding allows a maximum of one deployment at a time, leading to occasional difficult decisions about priorities when multiple crises occur almost simultaneously. Available funding also does not allow the VHP to hire replacements for those VDAP scientists who are prevented from carrying out their domestic assignments because of extended foreign commitments. Furthermore, budget constraints limit the number of scientists able to participate in crisis response activities. This in turn reduces the ability of the deployments to serve as training opportunities for workers responsible for domestic crisis response. The committee unconditionally supports the stated VHP desire to expand the size of the VDAP.

Partnership Issues

Crisis responses provide opportunities to better link the VHP with outside groups such as university faculty, foreign scientists, and emergency management officials. In the past, university researchers have commonly been excluded from the volcanic crisis situations coordinated by the VHP. Strengthening ties with faculty members and their students by integrating them into VDAP teams could provide long-term benefits to the VHP, by bringing in new perspectives and expertise, and to the greater volcanological community, by helping to train the next generation of volcanologists. There must, however, be clear ground rules for such participation, especially in international responses, because non-VHP personnel are not directly answerable to the local government. In particular, academic scientists should avoid increasing local confusion by offering opinions to the press or to civic officials that conflict with those

expressed by the coordinating government agency. The involvement of non-VHP personnel should contribute to the quality of the crisis response and to the VHP’s stated goal of improving forecasting ability. Students could be responsible for ongoing routine measurements and could provide help with data archiving, thus enabling the professional team to spend more time on data integration and assimilation. International responses should be coordinated with local investigators; VHP members have generally accomplished this and have developed professional relationships in other countries on the level of both individual scientists and institutions. One goal of this collaborative work should be greater use by all parties of deterministic forecasts based on theoretical models rather than more widespread, purely empirical approaches.

Establishing working relationships with local emergency management officials before the onset of a crisis is an important, though difficult, goal. The formulation of local emergency plans is an excellent way to set up these relationships before they are put under pressure in a crisis. Though the VHP has already been done much work in this area and good collaboration exists, this should be enhanced and expanded. As in all partnerships, the roles and responsibilities of all parties have to be defined clearly.

Another way to partner during volcanic crises is to use “expert elicitation” (Sidebar 4.2), a technique that relies on group expertise to evaluate and prioritize different scenarios when available data are inherently ambiguous. Recently, this approach was used to assess the likely eruptive behavior of the Soufriere Hills volcano on the island of Montserrat. A globally distributed group of experts set up a decision tree to attempt to forecast future volcanic behavior. Probabilities of specific eruptive outcome “branches” (timing, magnitude, products) on this tree were estimated by the collective best judgment of the participants. The group was re-polled periodically to allow members to debate, incorporate, and respond to the latest events. In this way an assessment could evolve continuously, in parallel with changing eruptive conditions. It allows individuals to focus on those factors that are the most uncertain. This is a promising approach that has to be refined through wider application, both inside and outside the VHP.

|

SIDEBAR 4.2 Expert elicitation is a useful technique when data are open to alternative interpretations, yet decisions based on these data must be made. In some implementations of expert elicitation, such as during the extended volcanic crisis at Soufriere Hills volcano, Montserrat, a hazard event tree is constructed and transition probabilities are estimated by a team familiar with the volcano and likely eruption outcomes. Event trees, which may vary from volcano to volcano, graphically illustrate the potential outcomes of volcanic unrest and eruption in a clear sequence.  The likelihood of activity progressing to a given state is governed by transition probabilities at each branch of the hazard event tree. Each of these transition probabilities is debated and estimated by the expert team. In an expert elicitation during volcanic unrest, each expert volcanologist would have to create such a logic tree and defend the branches and the transition probability that she or he estimates for each possible outcome. Ideally, this would make the reasons for variation in the estimated transition probability clear. The advantages of using event and logic trees during episodes of volcanic activity include the following:

|

|

A point to remember is that consensus is not always correct. Expert elicitation is not a substitute for data, and the elicitation is most valuable when it is treated as a very dynamic process in which probability distributions change continuously as the analysis proceeds. Provided this is understood, expert elicitation can be a useful tool to explore variation in likely outcomes and to understand the origins of uncertainty in eruption forecasts. |

HOW DOES CRISIS RESPONSE RELATE TO PUBLIC OUTREACH?

Just as the acquisition of volcanic knowledge takes place within a continuum between process-related research and hazards assessment, so does the application of this knowledge occur within the spectrum between crisis response and public outreach. The USGS in general and VHP workers in particular see their primary role as being advisory to civic officials responsible for making decisions about public welfare, rather than devising such policy themselves. This distinction leads to some potentially awkward situations, since the communities surrounding an active volcano have great interest in the information obtained by VHP geoscientists and apply pressure to politicians to make it available. The VHP must remain sensitive and responsive to the public’s desire for interpreted hazard data, especially during a crisis. At the same time it has to avoid creating panic by releasing premature or inadequate information about ongoing or imminent eruptions.

Recent improvements in mapping and monitoring techniques and expansion of the Internet and telecommunications infrastructure mean that opportunities for the VHP to communicate with the public are greater than ever. Thus, in the United States, eruptions are less likely to have unexpected and disastrous consequences than in the past. On the other hand, as populations, economic development, and tourism increase in volcanically active regions, the VHP will face greater pressure to continuously update and improve existing hazard assessments and to keep the public informed about the status of nearby volcanoes.

In a crisis situation, the scientist in charge of the relevant observatory plays a crucial communication role. Although the USGS is not responsible for acting on the hazard assessments it produces, once a crisis develops the scientist in charge can and should provide clear evaluations of the evolving situation to all involved public officials. To the extent possible, the scientist in charge must have already established

trust among members of other government agencies and the public so that their recommendations will be taken seriously.

In times between volcanic crises, communication and educational outreach remain essential functions of the VHP. Of the many forms of outreach, perhaps the most important is establishing good relations with local civil authorities, especially those concerned with emergency management. Many of these interactions require one-on-one briefings, but others consist of lectures, workshops, and field excursions during which dialogue is established with larger groups of officials. These individuals, once made aware of the hazards posed by volcanoes, play critical roles in disseminating this information to the concerned public and generating support for other VHP activities. Many VHP staff members, including the scientists in charge, have successfully carried out such communication.

The VHP also communicates directly with the broader public in many ways. These include one-page fact sheets, simple maps and brochures, videos, exhibits, booklets, and presentations to citizen groups. In recent years, large amounts of information have been made available through observatory Web sites. Members of the HVO staff write a weekly article entitled “Volcano Watch” that is published in a local newspaper, and a group of volcano specialists from the CVO has set up a “volcano hazards booth” at the Western Washington State Fair, downslope from nearby Mount Rainier. Collectively, these products and activities reach a broad cross section of the public and do a good job of informing them about volcanoes and associated hazards.

What Are Some Obstacles to Successful Outreach?

Although the committee finds the VHP’s varied outreach activities to be highly successful, there are some steps that the VHP, the USGS in general, and DOI could take to improve these programs. Many VHP outreach products, such as maps, booklets, and other “hard-copy” items, are sold at museums and other public institutions. However, either by law or by USGS policy, the program cannot retain proceeds from these sales. This is unfortunate, because the income could be reinvested, providing both the incentive and the means to generate new outreach products or to disseminate existing ones more widely. The National Park Service (NPS) has addressed this situation by fostering “natural history

associations” to promote the interests of many of its parks. These associations, outside the official NPS structure but located within park boundaries, operate much like usual nonprofit enterprises and are able to retain proceeds from the items they sell. A USGS “Volcano Hazards Association” might operate in much the same way, promoting sales of VHP products and ensuring that profits are retained for future outreach activities.

Similarly, USGS policy dictates that flyers and other inexpensive VHP outreach products be distributed free of charge to the public. Some of these materials are in great demand and are given out in large numbers. Paradoxically, the success of these items poses a problem for the VHP because the program bears all costs for their production and distribution. The result is a disincentive to disseminate these popular items because the costs involved constrain other outreach activities of the VHP.

There is a widespread belief within the VHP that staff members who devote significant time to outreach are penalized in the USGS performance review process. Although many public statements extol the importance of outreach, when it comes time for promotions, work in this area is thought to interfere with, rather than help, career advancement of scientists. The committee was told that at present, only senior scientists who have reached the top rungs of the career ladder and expect no further promotions can safely involve themselves with outreach. Those at lower organizational levels hesitate to divert their careers to such nonscientific pursuits. Administrative supervisors have to change this perception by suitably recognizing effective public service. The committee believes that there should be adequate rewards, at all levels, for involvement in outreach activities.

SUMMARY

Crisis response procedures at VHP observatories are well integrated and applied to hazards mitigation. VDAP, while evoking strong praise from the committee, needs to be strengthened, in both personnel and budget. The committee urges wider involvement of VHP personnel in VDAP activities, which—besides providing depth to the VDAP—would permit a wider circle of scientists to gain firsthand experience with volcanoes in crisis. Data gathered during international volcano crises

must be better archived and, where appropriate, published. The committee realizes that data acquisition and use can be a sensitive issue with foreign governments and organizations but urges that protocols be explored to improve the ways in which data from one overseas crisis might be better integrated and applied to the next crisis. Existing outreach products of the VHP were judged by the committee to be of high quality and effective in helping mitigate volcano hazards. This effectiveness can be increased by developing ways for the VHP to retain proceeds from the sale of these products and by removing the impediments that limit the involvement of midcareer VHP personnel in their preparation and dissemination.