1

The Corps and U.S. Flood Damage Reduction Planning, Policies, and Programs

Organized in 1802, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has long been a key player in helping reduce flood damages in the United States. The Corps's role in addressing the nation's flood problems was solidified with passage of the Flood Control Act of 1936. This act established flood control (generally referred to today as “flood damage reduction” by the Corps) as a nationwide policy on navigable waters and their tributaries, and it deemed flood control as an appropriate activity for the federal government.

One of the Corps's primary means for helping reduce flood damages has been levee construction. The Corps has constructed thousands of miles of levees that reduce flood damages for hundreds of American cities and thousands of acres of farmland. Uncertainties in the frequency of floods, changes in land use, climate variability and change, and the structural and geotechnical performance of levee systems complicate the levee design process. Furthermore, levee certification criteria and federal flood insurance policies, factor into flood hazard mitigation strategies.

The Corps has long recognized that uncertainties affect levee design and performance. To account for uncertainties, the Corps has historically established levee heights to pass a flood of a given recurrence probability. This flood has often been the flood with a probability of 1/100 of being exceeded in any given year, commonly called the “100-year flood ” and herein referred to as the 1%-flood. An increment of levee height, called “freeboard,” was then added to the levee design height. This freeboard was intended to account for operational contingencies, level-of-protection assurance, embankment settlement, and the like. But in his-

torical Corps guidance, freeboard was not considered as a “factor of safety,” per se. As described by Huffman and Eiker (1991),

“Conceptually, freeboard is provided to reasonably assure that the project design flow will be contained, given the uncertainty of water surface profile computation, and to minimize the damage and any threat to life in the event the levee is overtopped. In the design of freeboard it is convenient to consider that freeboard has two primary purposes (1) to achieve specific design objectives, and (2) to allow for the uncertainty inherent in the computation of a water surface profile. ”

A river at flood stage bears little resemblance to a lake on a calm day. It flows swiftly with rapids and waves, carrying trees, ice, and other flotsam. Waves or floating objects can overtop a levee, breeching it and causing flooding. Freeboard is a measure to prevent overtopping caused by higher water (river stage) than was forecast for the design flood, as some uncertainties may not have been explicitly considered. For decades, the Corps added 3 feet of freeboard to the design height of its levees, a principle that became a staple of Corps flood damage reduction studies and projects. The practice was also used by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in certifying levees under the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 (which created the National Flood Insurance Program) and two subsequent revisions (the Flood Disaster Protection Act of 1973 and the National Flood Insurance Reform Act of 1994).

Many levees have been designed, built, and certified to a standard equal to the 100-year flood plus 3 feet of freeboard. Nonetheless, this approach has drawbacks, and Corps engineers and planners, flood damage reduction project cosponsors, and others called this traditional standard into question during the 1990s. In particular, this fixed-freeboard approach provided inconsistent degrees of flood protection to different communities and provided substantially different levels of protection in different regions. In a narrow channel with variable hydraulics, a 3 foot safety margin may yield an unacceptably high probability of being overtopped. In a broad basin with overflow into storage areas, 3 feet may result in an exceptionally low probability of being overtopped.

RISK ANALYSIS APPROACH

In the early 1990s the Corps began to explore an alternative analytical approach to fixed freeboard. This alternative, referred to as riskbased analysis (RBA) by the Corps, is more generally known as risk analysis. A risk analysis approach uses probabilistic descriptions of the uncertainty in estimates of important variables, including flood–frequency, stage –discharge, and stage–damage relationships, to compute probability distributions of potential flood damages. These computed estimates can be used to determine a levee height that provides a specified probability of containing a given flood.

The Corps unveiled its basic proposal for using risk analysis techniques to substitute for fixed levee freeboard at a 1991 workshop in Monticello, Minnesota (USACE, 1991a). In 1992, the Corps issued a draft engineering circular (EC) Risk-Based Analysis for Evaluation of Hydrology/Hydraulics and Economics in Flood Damage Reduction Studies (EC 1105-2-205). In 1994, the Corps updated this engineering circular. In March 1996, the Corps issued engineering regulation (ER) 1105-2-101, which represents current Corps policy and procedures for risk analysis (USACE, 1996a). The Corps currently employs risk analysis across several of its civil works activities for water resources project planning. In addition to the Corps's internal planning procedures, risk analysis also influences the levee certification process that the Corps conducts jointly with FEMA.

As part of the Water Resources Development Act of 1996 (WRDA 96), the National Academy of Sciences (now part of the National Academies) was requested to conduct a study of the Corps's risk analysis methodology in its flood damage reduction studies. The 104th Congress of the United States passed Public Law 104-303 on October 12, 1996, which states in Section 202h the following:

The Secretary (Army) shall enter into an agreement with the National Academy of Sciences to conduct a study of the Corps of Engineers ' use of risk-based analysis for the evaluation of hydrology, hydraulics, and economics in flood damage reduction studies. The study shall include—

-

an evaluation of the impact of risk-based analysis on project formulation, project economic justification, and minimum engineering and safety standards; and

-

a review of studies conducted using risk-based analysis to

-

determine—

-

the scientific validity of applying risk-based analysis in these studies; and

-

the impact of using risk-based analysis as it relates to current policy and procedures of the Corps of Engineers.

A committee of the National Research Council's (NRC) Water Science and Technology Board (WSTB) was convened in late 1998 to address this charge, completing its study in May 2000.

THE CORPS'S WATER RESOURCES PROJECT PLANNING PROCEDURES

The Corps's use of risk analysis techniques is applied to certain hydrologic, hydraulic, geotechnical, and economic aspects of Corps planning decisions for flood damage reduction studies. Development, refinement, and application of these risk analysis techniques occur within a larger context of Corps planning procedures, federal planning guidelines, and other considerations. This section describes Corps planning and decision making in its water resources projects and draws partly from a recent National Research Council study (NRC, 1999a) of the Corps's planning procedures.

The Corps has been conducting studies and constructing projects to manage the nation's waterways for nearly 200 years. In addition to its flood damage reduction responsibilities, the Corps enhances and maintains navigability on the nation's rivers (some Corps dams also generate hydroelectric power). In its Civil works program for water resources development, the Corps is also involved in harbor improvements, hurricane damage prevention, and beach and shoreline protection. The Corps is also becoming more involved in ecosystem restoration; for example, the Corps plays a key role in the current effort to restore aquatic ecosystems in Florida's Everglades.

Several pieces of federal legislation and internal Corps planning documents guide Corps water resources project planning. One important document is the federal Economic and Environmental Principles and Guidelines for Water and Related Land Resources Implementation Studies (USWRC, 1983), familiarly known as the Principles and Guidelines, or simply the P&G. The Corps's Planning Guidance Notebook (USACE, 2000) is another key document, and contains advice on implementing the Principles and Guidelines within Corps planning studies. Corps plan-

ning procedures are further governed by the Digest of Water Resources Policies and Authorities (USACE, 1999a), guidance letters, and the Corps's own engineering regulations, engineering circulars, and engineering manuals (EM). The Corps is also obliged to conduct its studies pursuant to federal and state legislation and regulations, such as the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969.

From Principles and Standards to Principles and Guidelines

The predecessor to the P&G was the Principles and Standards (P&S). Adopted as regulations in 1973, the Principles and Standards is formally known as Water and Related Land Resources: Establishment of Principles and Standards for Planning (USWRC, 1973). This document defined four sets of objectives for U.S. federal water resources project plans: (1) national economic development (NED), (2) environmental quality (EQ), (3) regional economic development (RED), and (4) other social effects (OSE).

According to the Principles and Standards, water resources projects were to be evaluated primarily by their effects on the first two objectives—national economic development and environmental quality. The National Economic Development alternative was the water development plan that maximized economic development benefits for the nation, while the Environmental Quality alternative was the plan designed to minimize negative environmental impacts. The two secondary objectives, regional economic development and other social effects, could be assessed but were not required for all projects. The Principles and Standards also required that nonstructural alternatives be considered, that environmental mitigation measures be evaluated, and that a water conservation plan be included among the alternatives.

Although the Principles and Standards represented “the most detailed attempt to insure a broad range of choice in United States water planning” (Wescoat, 1986), they were repealed in 1982 and replaced by the Principles and Guidelines in 1983. The Principles and Guidelines represented an important departure from the Principles and Standards in at least two ways. First, with the change from “standards” to “guidelines,” the planning document became merely recommended guidance rather than a requirement, thereby losing much of its regulatory force. Second, the Principles and Guidelines required the development of only one water project alternative, the National Economic Development alternative. According to the P&G, this alternative is to “contribute to the

national economic development consistent with protecting the Nation 's environment, pursuant to national environmental statutes, applicable executive orders, and other Federal planning requirements” (USWRC, 1983). Box 1.1 provides further discussion of the Principles and Guidelines and the National Economic Development alternative, especially as that alternative relates to flood damage reduction studies.

The Principles and Standards and the Principles and Guidelines were both established by the U.S. Water Resources Council (WRC1). The Water Resources Council was an executive-level agency created in 1965 to help coordinate and centralize federal-level water resource planning. The Water Resources Council was zero-funded in 1981 and therefore effectively terminated.

The Principles and Guidelines describe a six-step planning process:

-

specify problems and opportunities,

-

inventory and forecast conditions,

-

formulate alternative plans,

-

evaluate effects of alternative plans,

-

compare alternative plans,

-

select recommended plan.

The Corps uses these steps in its water resources planning, although they are not necessarily applied in this sequence. Formulation of plan alternatives, for example, may occur at various stages throughout a planning study.

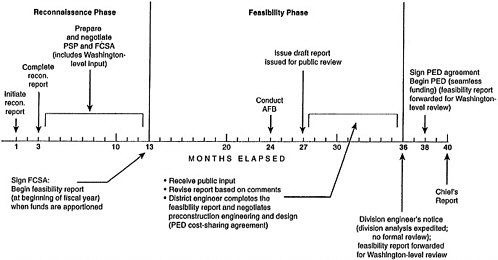

The Corps conducts its water resources project planning studies in two separate phases: a reconnaissance phase and a feasibility phase. An idealized time line showing these two study phases is depicted in Figure 1.1. (See NRC 1999a for a more detailed discussion of the Corps's water resources planning procedures).

The reconnaissance phase of a Corps planning study is conducted to determine whether a water or related land resources problem warrants federal participation in feasibility studies and to define the federal interest, consistent with U.S. Army policies (USACE, 1999a). The reconnaissance phase ends with a recommendation to either terminate or continue the study. This phase is to be completed in no more than 12 months, is to cost no more than $100,000, and is fully funded by the federal government. The reconnaissance phase of a Corps planning study is also used to create a project study plan, which describes the arrangements between the Corps and the project cosponsor for tasks beyond the reconnaissance study.

|

1 |

The Water Resources Council originally consisted of the secretaries of Agriculture, the Army, Commerce, Energy, Housing and Urban Development, the Interior, and Transportation and (starting in 1970) the administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency. |

|

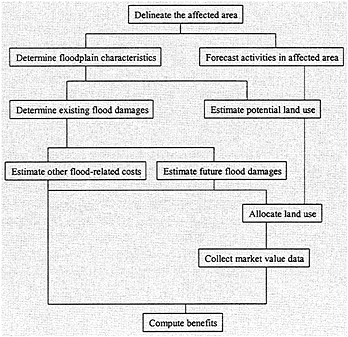

BOX 1.1 The Principles and Guidelines: National Economic Development and Flood Damage Reduction Studies The Principles and Guidelines (or P&G) is a key guidance document for all Corps of Engineers water resources project planning studies, including flood damage reduction studies, and has been referred to as the Corps's “philosophical source document ” (Yoe and Orth, 1996). The Principles and Guidelines has its roots in the 1970 Flood Control Act, in which Congress identified four equal national development objectives for water resources project planning: 1) national economic development, 2) regional economic development, 3) environmental quality, and 4) social well-being. In 1971 the Water Resources Council (WRC) issued the Proposed Principles and Standards for Planning Water and Related Land Resources. Major changes from the 1970 Flood Control Act were that social well-being was dropped as an objective, and that a plan maximizing contributions to national economic development would be required. After two years of review, the WRC in 1973 published the Principles and Standards for Planning Water and Related Land Resources in the Federal Register. The Principles and Standards placed environmental concerns on an equal basis with national economic development. In 1983 the Principles and Standards were replaced by the Economic and Environmental Principles and Guidelines for Water and Related Land Resources Implementation Studies (P&G). A major change from the Principles and Standards was that environmental quality was dropped as a planning objective, leaving national economic development as the sole required water resources project plan. The “principles” comprise a two-page statement (Appendix C) that ensures consistent planning by the federal agencies that conduct water resources planning studies (the Corps, the Bureau of Reclamation, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, and the Tennessee Valley Authority). The “guidelines” consist of a) standards, b) National Economic Development (NED) procedures, and c) environmental quality evaluation procedures. Chapter 2 of the Principles and Guidelines describes the procedures for estimating benefits for a range of water resource project planning studies. The approach and philosophy to estimating benefits under the National Economic Development is to “estimate changes in national economic development that occur as a result of differences in project outputs with a plan, as opposed to national economic development without a plan” (Yoe and Orth, 1996). Chapter 2 of the P&G describes specific procedures for estimating National Economic Develop |

|

ment benefits for the following types of water resources planning studies: Municipal and Industrial (M&I) Water Supply; Agriculture; Urban Flood Damages; Hydropower; Inland Navigation; Deep-Draft Navigation; Recreation; Commercial Fishing; Other Direct Benefits; Unemployed or Underemployed Labor Resources; and NED Costs. The economics analysis in Corps flood damage reduction studies is conducted using a discount rate that reduces future benefits so that they can properly be compared to present costs. All benefit-cost comparisons are made using annualized benefits and costs over an expected project life. The discount rate is used so that the annualized cost in any year reflects the actual timing of the years in which the benefits and costs actually occur (this is discussed in greater in detail in Chapter 5 of this report). Section IV of Chapter 2, “NED Benefit Evaluation Procedures: Urban Flood Damage,” provides specific steps (see flow chart in Figure 1) for calculating benefits in a flood damage reduction study, as well as specific guidance on the types of benefits that can be included in calculating the NED alternative (see Table 1 below). Regarding the benefits in a flood damage reduction study allowed within the P&G planning framework, Section IV states “Benefits from plans for reducing flood hazards accrue primarily through the reduction in actual or potential damages associated with land use” (USWRC, 1983, p. 32). Section IV identifies three benefit categories: 1) inundation reduction benefit, 2) intensification benefit, and 3) location benefit. The Corps has applied these steps (Figure 1) and benefit estimation guidelines in its flood damage reduction studies for nearly twenty years without significant modification. While the Principles and Guidelines represented the state-of-the-art in water resources planning when they were enacted in 1983, there have since been significant advances in economic and other analytical techniques, advances in aquatic biology, and shifts in public values related to water and related resources. A previous National Research Council (NRC) committee, formed in part to discuss possible revisions to the P&G, recommended “that the federal Principles and Guidelines be thoroughly reviewed and modified to incorporate contemporary analytical techniques and changes in public values and federal agency programs ” (NRC, 1999a, p. 4). That NRC committee also reviewed the guidance offered by the P&G for federal flood damage reduction programs, and concluded: “the P&G do not allow for the benefits of primary flood damages avoided to be claimed as benefits in all nonstructural projects. The committee recommends that the benefits of flood damages avoided be included in the benefit-cost analysis of all flood |

At the end of the reconnaissance stage, the Corps and the project cosponsor sign a feasibility cost sharing arrangement describing the details of project cost-sharing. Many terms of the feasibility cost-sharing arrangement are nonnegotiable, having been specified in legislation (e.g., the Water Resources Development Act of 1986).

Feasibility study costs are divided equally between the federal government and the project cosponsor. Risk analyses are conducted in the feasibility phase of a Corps flood damage reduction study. Alternative plans are identified at the beginning of the planning process and these

plans are screened and refined in subsequent iterations (USACE, 1999a, p. 5-4). As the Principles and Guidelines state, however, “A plan recommending Federal action is to be the alternative plan with the greatest net economic benefit consistent with protecting the Nation's environment (the NED plan), unless the Secretary of a department or head of an independent agency grants an exception to this rule” (USWRC, 1983).

The National Economic Development alternative does not necessarily represent the Corps's or the local sponsor's preferred alternative. The Corps will construct water resources projects in accord with a project sponsor's wishes and will share the costs of that project. Corps water resources project cost-sharing guidelines are specified in the Water Resources Development Act of 1986 (WRDA 86) and are modified in WRDA 96. But if a local sponsor desires a project that is larger or more costly than the National Economic Development alternative, then the local sponsor is responsible for at least a portion of the extra cost. For example, a local project sponsor is responsible for 100 percent of the extra costs of levees built higher than the elevation of the National Economic Development levee alternative.

The Principles and Guidelines requirement that the Corps select the alternative that maximizes net economic benefits to the nation has important implications for risk analysis applications and the construction of Corps levees. In a Corps flood damage reduction study, levee height is determined according to the National Economic Development criterion (i.e., based on prescribed benefit calculation procedures), rather than according to a levee's ability to withstand a flood of a given magnitude. As the Corps's Digest of Water Resources Policies and Authorities states, “There is no minimum level of performance or reliability required for Corps projects; therefore, any project increments beyond the NED plan represent explicit risk management options” (USACE, 1999a).

These issues can be problematic when, for example, a community requests the Corps to construct a levee for protection against an extreme flood, such as a 200-year flood (e.g., the flood with a probability of 1/200 of occurring in any given year). The Corps will pay the federal share of the National Economic Development levee (a minimum of 50 percent and a maximum of 65 percent of levee construction, pursuant to WRDA 86 and WRDA 96 cost-sharing guidelines); the local community, however, must bear the additional cost of constructing a levee higher than the level designated in the National Economic Development alternative. For instance, assume the Corps's National Economic Development alternative calls for a levee that provides protection only up to the 85-year flood. In this case the local sponsor would be required to pay

100 percent of the additional cost of raising the levee to protect against floods that exceed the 85-year flood. Such costs can be significant even when the additional levee height appears to be small. Engineers remind us that levees are raised from the bottom, not from the top.

Corps of Engineers levees figure prominently in the National Flood Insurance Program, which is conducted under the authority of FEMA. The following section describes the roles played by FEMA and other federal agencies in flood hazard mitigation, response, and recovery activities, and Chapter 7 discusses the Corps–FEMA levee certification program in more detail.

U.S. FEDERAL FLOOD PREPAREDNESS, MITIGATION, AND RESPONSE ACTIVITIES

Just as land use planning in the United States is not a federal responsibility, neither is comprehensive land use planning in the nation's floodplains. Nonetheless, federal agencies conduct extensive flood hazard reduction programs. Despite an impressive array of activities, however, no one agency coordinates these programs and there are no comprehensive floodplain management plans at the federal level. Although it is a key federal agency involved in flood hazard management, the Corps 's flood damage reduction activities are but a part of a larger effort —which includes other federal, state, tribal, and local governments —toward managing flood risks. Box 1.2 summarizes flood-related activities conducted by other federal agencies.

The Corps of Engineers today uses the term “flood damage reduction,” as opposed to flood control. This is consistent with recognition that no flood damage reduction program can provide complete protection against all floods. As demonstrated in the Mississippi River flooding of 1993 and in the extreme flooding in eastern North Carolina in 1999, there are classes of floods that exceed most, if not all, human experience and simply cannot be fully controlled by reasonable engineering structures. Thus, despite the best efforts of several federal, state, tribal, and local agencies and organizations, it bears repeating that no program or set of engineering structures can provide absolute control of all floods.

The Corps's flood-related programs have historically been in the realm of “structural measures”: dams, reservoirs, levees, walls, diversion channels, bridge modifications, channel alterations, pumping, land treatment, and related structures intended to modify the flow of flood waters through storage or diversion. The Corps has also implemented “non-

structural” flood damage reduction projects. Section 212 of the Water Resources Development Act of 1999, for example, authorized the Corps's “Challenge 21” initiative. This legislation calls for the Corps (in cooperation with FEMA) to “undertake a program for the purpose of conducting projects to reduce flood hazards and restore the natural functions and values of rivers throughout the nation” (H.R. document 106-298, 1999). It further states that “the studies and projects shall emphasize, to the maximum extent practicable and appropriate, nonstructural approaches to preventing or reducing flood damages.”

The “Galloway Report”

A comprehensive review of U.S. floodplain management activities was conducted by a special Interagency Floodplain Management Review Committee following the tremendous Mississippi River flooding in the summer of 1993. The committee was headed by U.S. Army Brigadier General Dr. Gerald Galloway; its report is thus more familiarly known as the “Galloway Report.”

The report pointed out the lack of inter-agency coordination in floodplain management, identifying this fragmentation as one of the nation' s major flood management problems: “the division of responsibilities for floodplain management among federal, state, tribal, and local governments needs clear definition. Currently, attention to floodplain management varies widely among and within federal, state, tribal, and local governments” (IFMRC, 1994, p. vii).

The Galloway Report emphasized that floodplain management is a responsibility that must be shared among all levels of government. To help promote better coordination, the report recommended the following actions:

-

The president should enact a Floodplain Management Act which establishes a national model for floodplain management, clearly delineates federal, state, tribal, and local responsibilities, provides fiscal support for state and local floodplain management activities, and recognizes states as the nation's principal floodplain managers;

-

Issue an Executive Order clearly defining the responsibility of federal agencies to exercise sound judgement in floodplain activities; and

-

Activate the Water Resources Council to coordinate federal and federal-state-tribal activities in water resources; as appropriate, reestablish basin commissions to provide a forum for federal-state-tribal coordination on regional issues.

|

BOX 1.2 U.S. Federal Flood Hazard and Floodplain Management Several federal agencies other than the Corps of Engineers and FEMA conduct flood damage mitigation, response, and recovery activities. This box does not describe all such programs but indicates the variety of federal-level activities. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) provides emergency loans to farmers impacted by floods. The loans cover losses to crops, livestock, and farm buildings and machinery. The USDA's Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) operates an Emergency Watershed Protection Program, which conducts local-level damage assessment and recovery planning (sometimes in cooperation with FEMA). The NRCS also provides technical assistance to local sponsors in a variety of watershed protection and conservation programs, some of which aim to reduce the magnitude of floods. The USDA's Farm Service Bureau oversees the Flood Risk Reduction Program, in which farmers contract to receive USDA payments on flood-prone lands in return for foregoing certain USDA program benefits. The USDA's Risk Management Agency sponsors a crop insurance program; about 22% of crop losses in the U.S. are caused by “excess moisture” (USDA, undated). The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has federal responsibility for assisting citizens with health and medical problems during floods and other emergencies. The HHS Office of Emergency Preparedness (OEP) coordinates federal health and medical response and recovery activities for HHS, working with other federal agencies and the private sector. HHS is the primary agency for health, medical and health-related social services under the Federal Response Plan, which provides for medical, mental health and other human services to disaster victims. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) provides Community Development Block Grants to communities damaged by floods and other disasters. HUD's Disaster Recovery Initiative (DRI) Grants provide financial assistance to low- and moderate-income families that may have extreme difficulties in rebuilding after floods and other disasters. HUD employees also provide technical expertise in housing and construction to local officials as they develop strategies to rebuild and renovate communities after floods. The Department of Transportation (DOT) operates the Federal-Aid Highways Emergency Relief (ER) program within the Federal Highway Administration. The ER program provides states up to $100 million in emergency relief funding for highways damaged by floods or other natural disasters. |

|

The Federal Emergency Management Agency's (FEMA) flood-related responsibilities revolve around flood mitigation, response, and recovery activities and its administration of the National Flood Insurance Program. Communities can participate in the National Flood Insurance Program if they agree to regulate future floodplain construction by assuring that future structures are built to safe standards. For participating communities, FEMA makes federal flood insurance policies available to property owners (flood insurance is not underwritten by private insurers). As of May, 2000, federal flood insurance through the NFIP was available in over 19,000 communities in the U.S. and Puerto Rico. FEMA also conducts a variety of other programs related to flood hazard mitigation and response activities. For example, FEMA's Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) provides funding to assist states and communities in implementing measures to reduce or eliminate the long-term risk of flood damage to buildings, manufactured homes, and other structures insurable under the National Flood Insurance Program. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) is involved in flood hazard reduction through an agency-wide effort, the “Natural Disaster Reduction Program: Space Access and Technology, Management Systems and Facilities, Life Sciences, and Space Communication.” Within this program, NASA's Solid Earth and Natural Hazards Program aims to improve local and regional flood forecasts by incorporating satellite-derived data on parameters such as topography, land cover, and soil moisture into watershed modeling research. NASA also conducts research on the consequences of inter-annual climate variability for rainfall and storm patterns. The National Weather Service (NWS) sponsors the Hydrologic Information Center (HIC), which prepares national summaries of hydrologic conditions, including river conditions with emphasis on extreme events such as floods. In late winter and early spring, the HIC issues national outlooks for flood conditions based on data from its river forecast centers, weather forecast offices, and national Centers. The NWS also provides data on fatalities and some loss estimates in floods. The Small Business Adminstration (SBA) operates a Disaster Loan Program that offers financial assistance through low-interest (4-8%) loans for renters, and home and business owners, who have suffered damages from a flood or other natural disaster. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) operates a nation-wide system of stream gages that provides data used in making flood forecasts. The USGS is currently helping FEMA update its flood inundation maps through the use of geographic information system (GIS) technology, high-accuracy digital elevation data and models, and existing hydraulic models. The USGS also compiles and reports information on major floods across the nation. |

The report also recommended goals for floodplain management: “Establish, as goals for the future, the reduction of the vulnerability of the nation to the dangers and damages that result from floods and the concurrent and integrated preservation and enhancement of the natural resources and functions of floodplains. Such an approach seeks to avoid unwise use of the floodplain, to minimize vulnerability when floodplains must be used, and to mitigate damages when they do occur” (IFMRC, 1994, p. viii).

This chapter has described the planning, policy, and inter-agency context in which the Corps executes its flood damage reduction studies and plans. Although the Corps plays several important roles, they clearly are but a part of larger efforts in flood damage reduction. And, as the Galloway Report stressed, the different components of that effort require much better coordination than they have had to date. These inter-agency relations are further examined in Chapter 7, which describes coordination between the Corps and FEMA in a federal levee certification program within the National Flood Insurance Program.