The achievement of health equity in the United States should be built on strengthened nursing capacity and expertise.

For the United States to advance health equity for all, the systems that educate, pay, employ, and enable nurses need to:

For too long, the United States has overinvested in treating illness and underinvested in promoting health and well-being and preventing disease. Health disparities in the country are stark: data show that people with higher levels of wealth live longer, those without health insurance are less likely to receive preventive care, and structural racism has contributed to public health crises, such as mass incarceration, that disproportionately impact people of color.

Even before COVID-19 illuminated such disparities and exacerbated inequities in the United States, nurses were advocating for better care and access for individuals, families, and communities.

At the request of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a National Academy of Medicine committee conducted a study aimed at charting a path forward for the nursing profession to help ensure that all people have what they need to live their healthiest lives. The report was published in May 2021 and builds on progress nurses have made over the past decade.

Explore this toolkit to understand how the United States can unleash the power of the nurse to achieve health equity for all.

“The state in which everyone has the opportunity to attain full health potential and no one is disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or any other socially defined circumstance” (NASEM, 2017).

The conditions of the environments in which “people live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks” (HHS, 2020).

Over the next decade, both the nation and the nursing workforce will face dramatic changes: more than 1 million registered nurses are expected to retire, the country’s aging population will become more diverse, health care needs will become more complex, and nurses will have to address the lingering physical and mental health effects of COVID-19.

Structural Racism: “The processes of racism that are embedded in laws, policies, and practices of society and its institutions that provide advantages to racial groups deemed as superior, while differentially oppressing, disadvantaging, or otherwise neglecting racial groups viewed as inferior” (Williams et al., 2019, p. 107).

Cultural Racism: “The ideology of inferiority in the values, language, imagery, symbols, and unstated assumptions of the larger society” (Williams et al., 2019, p. 110).

Discrimination: Occurs when people or institutions treat racial groups differently, with or without intent, and this difference results in inequitable access to opportunities and resources (Williams et al., 2019).

The achievement of health equity in the United States should be built on strengthened nursing capacity and expertise.

For the United States to advance health equity for all, the systems that educate, pay, employ, and enable nurses need to:

Policymakers need to expand scope of practice for advanced practice registered nurses, including nurse practitioners, and registered nurses.

Employers need to remove institutional barriers, such as telehealth restrictions and restrictive workplace policies.Public and private payers need to establish sustainable and flexible payment models to support nurses working in health care and public health. This includes school nurses, a group that is consistently undervalued and underutilized.

Preparing nurses should take many forms.

Nursing education programs need to strengthen education curricula and expand the environments where nurses train to better prepare nurses to work in and with communities.

Federal agencies, employers, nursing schools and other stakeholders need to strengthen the capacity of the nursing workforce to respond to public health emergencies and natural disasters, while also protecting nurses on the frontlines of this work.

Employers need to support nurse well-being so nurses can in turn support the well-being of others. They, along with other stakeholders, should create and implement systems and evidence-based interventions dedicated to fostering nurse well-being.Nursing schools need to intentionally recruit, support, and mentor faculty and students from diverse backgrounds to ensure that the next generation of nurses reflects the communities it serves.

Nursing accreditors can play a role by requiring standards for student diversity just like other health professions schools.

Everyone, no matter who they are or where they live, needs access to high-quality, affordable health care and opportunities so they can be healthy and well. But as of March 2020, more than 80 million people—roughly one-quarter of the country—lived in an area with a shortage of health professionals.

Nurses at all levels and in all settings have the education, skills, experience, and training to fill this critical care gap and address health disparities—if they are given the autonomy and institutional support to do so.

Expanding scope of practice for advanced practice registered nurses, including nurse practitioners, would significantly increase access to care, particularly in rural and underserved communities. During the pandemic, eight states expanded scope of practice for nurse practitioners. But, 27 states still restrict full practice authority for them.

Nurses at all levels and in all settings face institutional barriers to fully leveraging their skills to advance health equity. These range from restrictions on providing telehealth services to workplace policies that prevent them from providing the best care possible.

Increasing Care to Combat the Opioid Crisis

To address the opioid crisis, a 2017 federal waiver allowed nurse practitioners and physicians assistants to prescribe buprenorphine. This significantly increased access to care in some rural communities and kept many people experiencing addiction safe.

Improving the health of all people should drive how the U.S. pays for health care and public health. But that’s not how the current system works.

The current healthcare payment system prioritizes volume of care and underestimates the value nurses bring in addressing obstacles to good health, such as poverty and discrimination, and in expanding access to care.

For example, payment systems often reimburse for physicians’ services—excluding services of other care providers, including nurses, and team-based care. Many nurses are also unable to bill for telehealth services.

Value-based payment models and alternative payment models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and accountable health communities (AHCs) link quality of services and value, thus focusing on outcomes that advance health equity.

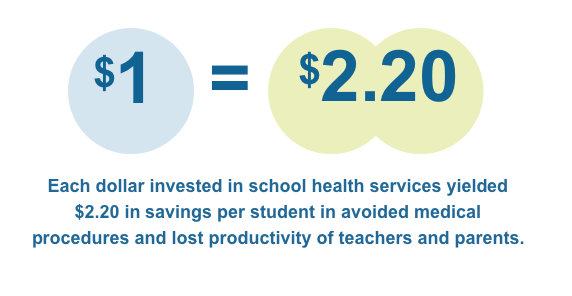

Support for community and public health nursing is one area with glaring gaps. For instance, though school nurses are a lifeline for 56 million students, particularly for children from low-income families, the average school nurse works simultaneously across three schools and funding sometimes must be pieced together. But some evidence shows that money invested in school health services reaps real benefits.

Scaling the Impact of the School Nurse

Robin Cogan, MEd, RN, NCSN, a school nurse in Camden, N.J., has long seen the role that systems and factors like low income and nutrition have on a child’s health and well-being. After working for change at her own school, she partnered with fellow school nurses and public health officials in the region to understand what local parents needed. They started a “community cafés” initiative to hear directly from families about challenges they face. These conversations have led to work with local health care providers and discussions on topics ranging from the immigrant experience to father’s roles in their children’s lives. Cogan’s work has shown the powerful role school nurses play in reforming systems and building healthy communities.

Nurses at all levels and in all settings are not yet prepared to advance equity for all. Preparing them to address the evolving health, social, and economic needs of their communities should take many forms.

The pandemic has reinforced that all nurses should possess deep, empathetic, real-world knowledge and understanding of the social, economic, and environmental factors that affect health and well-being. But many nurses are still not taught about these issues in the classroom.

Most nursing schools cover health equity and the social determinants of health as a siloed topic, leaving nurses unprepared to work in a wide variety of settings and with people from diverse backgrounds.

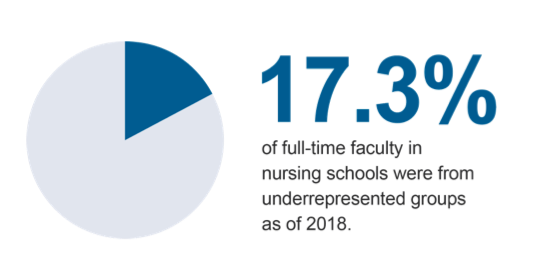

There is also a significant shortage of faculty, which played a role in nursing programs turning away otherwise qualified applicants.

Natural disasters and public health emergencies disproportionately affect people of color, those with low incomes, those experiencing housing insecurity, and those with limited access to health care and transportation.

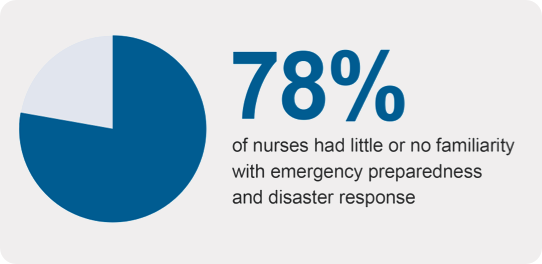

Nurses serve on the frontlines of these emergencies, helping people and communities cope and recover. But the U.S. nursing education, health care, and public health systems do not educate, prepare, equip, and support nurses to do this work, particularly through an equity lens:

As the COVID-19 pandemic has starkly revealed, responding to crises takes a serious toll on nurses’ mental and physical health. But nurses were experiencing a well-being crisis long before this:

Providing Real-World Training in Health Equity

In 2017, Washburn University and the Topeka Housing Authority partnered to open the Pine Ridge Family Health Center. A nurse practitioner leads the center, which focuses on providing care to community members, many of whom have low incomes and limited access to care. The university uses the center as an educational forum for students, including those from the School of Nursing, with a curriculum that covers topics ranging from social justice to trauma-informed care. The center is also a dedicated training site for nurse practitioner students, giving them real-world training in addressing the social determinants of health.

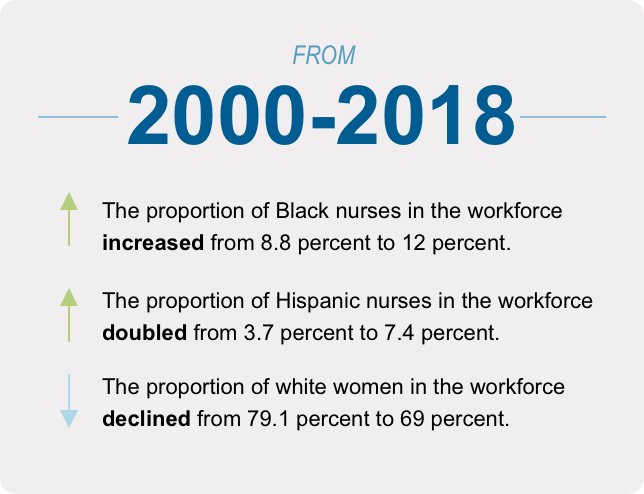

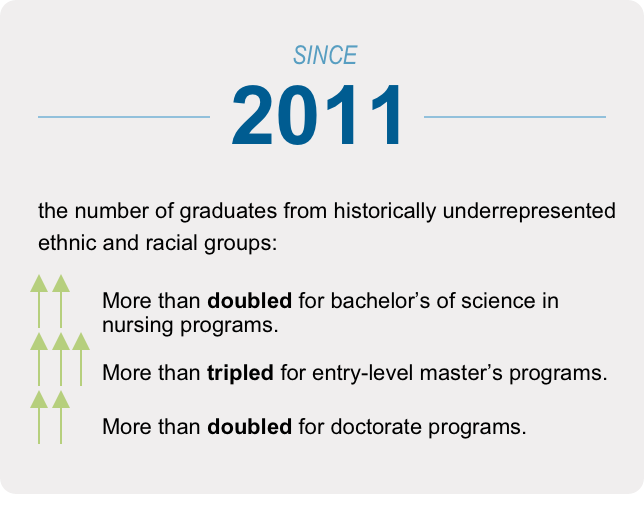

To better serve and understand the changing needs of the nation, it’s critical that the diversity of the nursing workforce reflects that of the country. Over the past few decades, the nursing workforce has steadily grown more diverse.

But, there are still significant cost, cultural, social, and awareness barriers that prevent people of color, those with low incomes, first-generation college students, and others from pursuing careers in the field—and particularly from pursuing advanced degrees.

Nursing program faculty are also overwhelmingly white and female. Currently, these faculty are not all prepared to educate students in the social determinants of health and health equity.

Creating a Pathway to Nursing that Starts in High School

Providing fair and equitable access to education will be key to diversifying the nursing workforce. The Rhode Island Nurses Institute Middle College Charter High School (RINIMC) is one model for this. The school provides a free, nursing-focused high school education for any student in Rhode Island. About half the program’s participants are Latinx and one-third are Black, and many come from underserved and low-income communities. Students graduate with real-world work experience and up to 20 college credits. The school also has agreements with multiple colleges in the state to offer students a direct, affordable path to a career in nursing. Seventy-nine percent of RINIMC’s graduates have enrolled in college within two years of graduating from the program.

Nurses at all levels and in all settings need to leverage their own power to advance health equity by:

Nurses can learn about the social determinants of health and health equity both in the classroom and through real-world experiences.

For instance, nurse Sarah Szanton, PhD, ANP, FAAN, had early career experiences working with migrant farmworkers in rural Pennsylvania and later made house calls to home bound older adults in west Baltimore. This work inspired her to co-create a program called CAPABLE (Community Aging in Place—Advancing Better Living for Elders), designed to help seniors with low incomes age safely in their own homes.

This can take many forms both in and out of the workplace.

One example: MINDBODYSTRONG, adapted from the COPE cognitive-behavioral skills-building intervention, is delivered by a nurse to new nurse residents. It is comprised of eight weekly sessions focused on caring for the mind, caring for the body, and building skills. Evidence from randomized-control experiments shows that MINDBODYSTRONG improves mental health, healthy lifestyle behaviors, and job satisfaction and sustains these impacts over time.

Nurses at all levels and in all settings can advocate for equity in their communities.

For instance, two nurses in Baton Rouge, LA—Terrie Sterling, MSN, MBA, RN, FACHE, and Coletta Barrett, RN, MHA, FAHA, FACHE—worked with the city’s mayor to establish a community group, Healthy-Baton Rouge, to address food insecurity, obesity, and social isolation.

National nursing organizations also need to work together to advance the report goals. In 2021, they should start to develop a shared agenda for addressing social determinants of health and achieving health equity. This agenda should include explicit priorities across nursing practice, education, leadership, and health policy engagement.