CHAPTER THREE

Education and Preparedness of Individuals, Communities, and Decision Makers

SUMMARY

This chapter reviews progress in education and emergency management in preparation for future tsunamis. Effective education and emergency management have been credited with saving thousands of lives in recent tsunamis elsewhere and can also save lives in future tsunamis that strike U.S. communities. Ultimately, the ability to survive a tsunami hinges on at-risk individuals having the knowledge and ability to make correct decisions and act quickly. For local tsunamis, waves will arrive within minutes after generation, and at-risk individuals need to understand that natural cues (prolonged ground shaking and shoreline draw down) may be their only warning. Local officials will not be capable of assisting them in the initial moments or even potentially for days, so individuals need to know how to respond with no official guidance. The knowledge and readiness they acquire through pre-event education could save their lives. For distant tsunamis, waves will arrive several hours after generation and individuals need to understand where official warnings may come from, how they may receive the warnings, what those warnings might say, and what they need to do in response to those warnings.

Although much has been done to educate at-risk individuals, prepare communities, develop and deliver warning messages, and coordinate agency procedures, the committee concludes that these efforts could be more effective with improved coordination, baseline assessments of the target audience, evaluations of effectiveness, transfer of best practices among the National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program (NTHMP) members, and use of evidence-based1 approaches in the social and behavioral sciences of education, warning messaging, and emergency management. The committee commends the intent of the federally administered TsunamiReady program to coordinate community preparedness efforts but finds major gaps between stated program goals and current accomplishments. The recommendations listed here in summary form include:

-

Systematic and coordinated perception and preparedness studies of communities with near-field tsunami sources.

-

Consistent education among NTHMP members using evidence-based approaches in the social and behavioral sciences that is evaluated and archived.

-

A TsunamiReady Program that is based on professional and modern emergency management standards.

-

A review of the format, content, and style of tsunami warning center (TWC) warning messages, and how dispatchers and emergency personnel understand the messages.

-

The consolidation of the two TWC messages.

-

Formal attention and planning given to outreach efforts at the TWCs.

-

Strong local/state working groups that share best practices and lessons learned.

-

Guidelines on the design and an inventory of tsunami-related exercises.

INTRODUCTION

Tsunamis are natural events that threaten coastal communities. Effective public education and emergency management can prepare individuals and reduce the likelihood of fatalities when tsunamis occur. Education is credited for saving thousands of lives during the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, the 2009 Samoan tsunami, and the 2010 Chilean tsunami (Box 3.1), and education will save lives in future tsunamis that strike U.S. communities. Ultimately, the ability to survive a tsunami hinges on at-risk individuals having the knowledge and ability to make correct decisions and act quickly. For local tsunamis, waves will arrive in minutes after generation and at-risk individuals need to understand that natural cues (e.g., prolonged ground shaking, shoreline draw down) may be their only warning, that local officials will not be capable of assisting them, and that the knowledge and readiness they acquire through pre-event education could save their lives. For tsunamis generated at greater distance from coastal communities, the ground shaking might be too weak to alert residents of the imminent danger, but waves may arrive anywhere from an hour to many hours after generation. In these instances, individuals need to understand where official warnings may come from, how they may receive the warnings, what those warnings might say, and what they need to do in response to those warnings.

Regardless of tsunami sources, integrated public education and preparedness planning provide the context in which individuals will perceive, process, and react to future warnings. Education and planning are long-term, ongoing efforts that strive to make tsunami knowledge and preparedness commonplace and ingrained into local culture and folk wisdom. Enculturation requires a major commitment and diverse efforts to achieve this goal; however, once accomplished, it can perpetuate itself. This chapter discusses four areas in which targeted education-related efforts can increase the likelihood that people will be able to evacuate before tsunamis arrive and that agencies will be able to execute effective evacuations, such as:

-

Educating at-risk individuals in advance about what they need to know to prepare for and respond to tsunamis;

-

Preparing communities for future tsunamis;

-

Developing and delivering effective warning messages; and

-

Improving interagency coordination, as well as coordination among all segments of the community (public and private), in preparing for and responding to tsunamis.

EDUCATION OF AT-RISK INDIVIDUALS

Tsunami education in U.S. coastal communities is a major challenge because it requires reaching hundreds of coastal communities that contain hundreds of thousands of residents, employees, and tourists. There are 29 NTHMP partner states, territories, and commonwealths, each a sovereign entity with sub-jurisdictions (e.g., counties, cities) that have individual needs, priorities, and resources for tsunami education. Tsunami education needs to also adequately convey the different tsunami threats and proper responses to each—local tsunamis that require instantaneous, self-protective action to reach higher ground based on the recognition of natural cues and distant tsunamis that involve orderly evacuations over several hours that are managed by officials and informed by the tsunami warning centers.

The NTHMP Mitigation and Education Subcommittee (M&ES) is tasked with assessing tsunami mitigation and education needs for the nation, addressing these needs through targeted products and activities, and then sharing these products with other at-risk coastal states, territories, and commonwealths. An NTHMP-approved strategic implementation plan for tsunami mitigation projects (Dengler, 1998, 2005) identifies education as a critical element in mitigation and states that effective education projects define the audience and their needs, assess existing materials, and define a strategy for sustained support. This plan also discusses the need for a resource center to provide information exchange and coordination. With guidance from the M&ES, NTHMP members develop their individual education projects to support the goals and objectives of the subcommittee and often collaborate on regional products that address common issues between members. This section provides an overview of the factors that influence the effectiveness of education and reviews progress in NTHMP education efforts. Conclusions and recommendations in this section center on the need to assess the needs and knowledge of the at-risk audience and on making NTHMP education efforts more coordinated, consistent, and subsequently, more effective.

Factors That Increase the Effectiveness of Education

A rich research base has been developed to address the question of how to enhance what the public knows and to motivate them to take actions to prepare for future hazards (Mileti and Fitzpatrick, 1992; Mileti et al., 1992; National Research Council, 2006). Based on the current literature, the committee highlights 10 practical steps to increase public knowledge of and readiness for tsunamis (Box 3.2). Effective public education on hazards has been found to correlate with many factors: dissemination content and channels, social and physical cues, the status and role of the recipient, past experience with hazard(s), beliefs about the informa-

|

BOX 3.1 Cautionary Tales and Education Saves Lives from Tsunamis Traditional knowledge saves lives in Aceh, Indonesia, during the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami: Some 78,000 people were living on Simeulue Island, off the west coast of Aceh, Indonesia, at the time of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Most lived along the coast in villages the tsunami would strike. The tsunami began coming ashore as soon as eight minutes after the shaking stopped and too soon for official warnings. Although hundreds of thousands of lives were lost elsewhere, only seven people on Simeulue died. What saved thousands of lives was knowledge of when to run to higher ground. This knowledge had been passed down within families over the years by repeating tales of smong—a local term that entails earthquake shaking, the withdrawal of the sea beyond the usual low tide, and rising water that runs inland. Smong can be traced to a tsunami in 1907 said to have taken thousands of Simeulue lives and reminders of that event reinforced the story, such as victims’ graves, a religious leader’s grave untouched by the tsunami, and coral boulders in rice paddies. After any felt earthquake, a family member would mention the smong of 1907 and often concluded with this kind of lesson: “If the ground rumbles and if the sea withdraws soon after, run to the hills before the sea rushes ashore.” By contrast on mainland Aceh, where education had suffered from years of military conflict, only a tiny fraction of the population used the giant 2004 earthquake as a tsunami warning. After the initial earthquake, many people gathered outdoors, fearing further damage from aftershocks. Most missed their opportunity to evacuate—a time window of 20 minutes on western mainland shores and 45 minutes in downtown Banda Aceh.1 Elementary education from afar saves lives in Phuket, Thailand, during the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami: More than 100 tourists and locals on Maikhao Beach in Phuket, Thailand, were saved when a 10-year-old girl from England persuaded them to evacuate to higher ground after the initial earthquake. While other tourists watched as the tide rushed out and boats in the distance bobbed up and down, Tilly Smith, who was in Phuket on holiday with her parents and younger sister, recognized these as natural cues of an imminent tsunami. Just two weeks earlier, Tilly had studied tsunamis in her prep |

tion, perceived risk, perceived effectiveness of actions, and warning confirmation (Mileti and Sorenson, 1990). Recent work suggests that education effectiveness primarily depends on the quality and quantity of educational materials received by the public and the physical and social cues observed. The other factors (e.g., status, roles, experience) play a role when information is of low quality and of insufficient quantity (Linda Bourque, UCLA, personal communication). Each of the factors is briefly described below.

Information dissemination. The effectiveness of education is increased when verbal and written information is frequently disseminated from multiple sources over multiple communication

|

school geography class in Surrey, England, and quickly realized everyone was in danger. She convinced her parents that everyone needed to evacuate, who then alerted other tourists and hotel staff, and people quickly evacuated. The waves started to flood the area a few minutes later, but no one on the beach was killed or seriously injured (The Daily Telegraph, 2005). School and community education saves lives in American Samoa during the September 2009 tsunami: The tsunami of September 29, 2009, took 34 lives in American Samoa but could have taken far more in the absence of tsunami education. September had been emergency preparedness month and tsunami education efforts, supported by the TsunamiReady program, included videos of the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and school tsunami evacuation practices. Long-term education efforts of the American Samoa Department of Homeland Security, in collaboration with Department of Public Works and National Weather Service Pago Pago, included school evacuation plans and awareness campaigns for agencies, schools, and businesses (Laura Kong, International Tsunami Information Center, written communication). After the initial earthquake ended, schools and community members knew to evacuate, and many did (Laura Kong, International Tsunami Information Center, written communication). In the community of Amenave, the mayor credited an earlier workshop for village mayors on tsunami hazards for his ability to recognize and then personally warn with a bullhorn his constituents of the potential for a tsunami after the earthquake (Earthquake Engineering Research Institute, 2010). Signage and other education products save lives in Chile during the February 2010 tsunami: Initial observations of post-tsunami survey teams suggest tsunami-savvy residents knew to use the parent earthquake as a natural warning to run to high ground. Several towns had posted tsunami hazard and/or evacuation-zone signage, some communities had practiced drills, and others had held preparedness workshops. Some survivors cite their memory of the Valdivia earthquake in 1960, while others cited various books, television, documentaries, and other media information as the source of their awareness (Lori Dengler, Humboldt State University, written communication). |

channels with consistent information regarding what recipients need to know and about actions that they should take (Mileti and Fitzpatrick, 1992; Linda Bourque, UCLA, personal communication).

Physical and social cues. Observing cues—when consistent with the verbal and written information that is being disseminated—can reinforce learning. Physical cues that reinforce knowledge include tsunami evacuation route signage and NTHMP-related household products (e.g., coffee mugs, refrigerator magnets); and social cues include preparedness drills and community workshops (Wood et al., 2002; Connor, 2005; Alexandra et al., 2009).

|

BOX 3.2 Practical Steps to Grow Public Knowledge and Readiness The following are recommendations for maximizing the effectiveness of tsunami public education, based on social science evidence (Mileti and Sorenson, 1990; Linda Bourque, UCLA, personal communication) and lessons learned from tsunami education efforts in Hawaii (Alexandra et al., 2009) and Oregon (Connor, 2005):

|

Statuses and roles. Factors that correlate with public hazard education effectiveness relate to status (e.g., having higher income, education, and occupational prestige, not being either young or old, being white, being female, and being native born) and roles (e.g., being in a partnership relationship, belonging to a larger family, and being responsible for children). A demographic analysis of at-risk population composition and distribution is a first step in developing targeted education for demographic sub-groups where education is not as effective (e.g., the very young, low-income families, foreign-born).

Experience. People are more inclined to be educated about and/or prepare for hazards that they have experienced. In communities where there haven’t been recent tsunamis to give individuals any personal experiences with tsunamis, community memory of past events can be sustained through oral histories of tsunami preparedness passed down through the generations (McMillan and Hutchinson, 2002; Box 3.1), disaster memorials (Iemura et al., 2008; Nakaseko et al., 2008), and survivor stories from recent tsunamis, such as the growing archive of survivor stories at the Pacific Tsunami Museum in Hilo, Hawaii (Dudley, 1999). Tsunami survivor stories and oral histories not only build hazard awareness but also increase the perception that tsunamis are survivable if certain actions are taken (Paton et al., 2008). Although experience can increase the likelihood that people prepare, personal experience also biases people to interpret educational information in the context of their own experience, which can either support or contradict their notion of the risk’s reality and severity. Prevalent myths and misunderstandings need to be addressed in education efforts because existing misperceptions may serve as obstacles and prevent people from hearing and correctly interpreting information (Connor, 2005; Alexandra et al., 2009).

Perceived risk and action effectiveness. At-risk populations have their own perceptions of risk which rarely match the calculations described by experts. Perceiving increased probabilities for events did not increase public readiness action-taking (Kano et al., 2008). Instead, an intentions-to-prepare model suggests people are more inclined to act on hazard education information when they believe their present actions can mitigate their future losses (Paton et al., 2008). Education efforts that dwell only on the uncontrollable aspects of tsunami hazards, specifically event probabilities, do not influence public action. Instead, risk awareness should be framed to include information on uncontrollable tsunami hazards and controllable individual consequences if a tsunami occurs, where individual actions can reduce these consequences. An example of this is information included on tsunami evacuation maps (e.g., maps in Oregon, Washington, and California) on how to prepare for tsunamis, develop emergency kits, and evacuate to safe areas if individuals recognize natural cues or receive an official warning.

Warning confirmation process. This process refers to individuals talking about educational topics with others, seeking more information from other sources and places on their own, and then making their own decisions about what they will think, do, and not do prior to taking any action (Quarantelli, 1984; Mileti, 1995). It is part of understanding how individuals convert information into actions (Quarantelli, 1984). Effective education incorporates activities that encourage people to talk about getting ready with each other, such as discussion groups during workshops (e.g., Wood et al., 2002; Connor, 2005; Alexandra et al., 2009).

Understanding the Local Risk Conditions and the Target Audience

Effective public education for tsunamis begins with an understanding of the risks that tsunamis pose to coastal communities (see Chapter 2) and of the existing knowledge and beliefs

of the target audience. For example, all at-risk communities would benefit from evacuation signage and educational programs regardless of tsunami source. Education to prepare individuals for far-field tsunamis would emphasize official warnings disseminated by tsunami warning centers and organized evacuations managed by local officials, whereas those for near-field tsunamis would instead emphasize the public’s ability to recognize natural cues and take timely protective actions for their own survival. Distinctions between warnings for near- and far-field tsunamis are important to convey to at-risk populations, because the public is often confused by differences between the two and this confusion can create false expectations (Connor, 2005).

The format and dissemination of education products also vary based on the intended audience. As discussed in Chapter 2, the demographics of the audience, such as age, income, or educational background, influence the ability of an individual to anticipate and react to a natural hazard (Wisner et al., 2004) and therefore are important considerations when designing evacuation signs and public education efforts. An education campaign designed for residents capitalizes on their familiarity with their surroundings, emphasizes household preparedness strategies, and could be delivered through existing social networks. An education campaign designed for tourists focuses on easily identifiable landmarks, assumes individuals would have no local friends or relatives to assist them in an evacuation, and would be delivered by employees in the tourist industry and through posted information on road-side signage, along coastlines, and in commercial establishments. The challenge of having employees serve as tsunami educators was made clear in a recent survey of hotel employees along the southwest Washington coast that indicated only 22 percent of interviewees said they had been trained about how to respond to tsunamis and had tsunami-related information available for guests (Johnston et al., 2007). However challenging, educating tourists and the businesses that serve them is critical—initial observations from the February 2010 Chilean tsunami suggest that tourists, specifically campers on an island campground, represented a significant percentage of the fatalities (Lori Dengler, Humboldt State University, written communication).

In addition to taking the local risk conditions into account, effective tsunami education is built upon an understanding of what the target audience already knows and believes. Building this knowledge requires conducting routine assessments (such as Dengler et al., 2008) of the at-risk population’s perception, knowledge, and capacity to respond, which provides officials with a baseline for measuring progress in awareness and preparedness. It is also useful in evaluating an educational program’s effectiveness, highlighting areas for improvement, and guiding officials in their evacuation planning. Case studies suggest that segments of coastal communities are aware of tsunami hazards, but may have difficulty evacuating if an event were to occur (Gregg et al., 2004, 2007; Johnston et al., 2005, 2007). A survey in Oregon and Washington revealed that although public officials and coastal business owners consider near-field tsunamis related to Cascadia subduction zone earthquakes to be significant threats, they had done little to make their own organization or office less vulnerable to these hazards (Wood and Good, 2005). Other studies confirm that current dissemination activities increase awareness but are inadequate to translate into increased preparedness or appropriate evacuation actions (Johnston et al., 2005, 2007; Gregg et al., 2007). Baseline measurements and post-outreach assessments documented positive changes in tsunami knowledge and prepared-

ness of at-risk populations after a series of recent tsunami outreach efforts in Seaside, Oregon (Box 3.3; Connor, 2005).

Knowledge assessments of the at-risk population can also be used for determining the effectiveness of warning systems. For example, a survey of 956 individuals from across Hawaii found that 59 percent of respondents did not understand the meaning of the tsunami-alert sirens, even though 69 percent of respondents also said that some sort of official warning would be their signal to evacuate from a tsunami (Gregg et al., 2007). Similar confusion of what sirens signify has been expressed during educational workshops in Hawaii (Alexandra et al., 2009). Surveys of Hilo, Hawaii, residents who survived the 1960 tsunami indicate that only 40 percent of people who heard warning sirens evacuated, whereas many people waited for additional information from other information sources (e.g., television, relatives) before evacuating (Bonk et al., 1960; Lachman et al., 1961). A survey of 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami survivors in Padang, West Sumatra, indicates that the majority of people received information through social networks and not through official channels (Birkman et al., 2008).

These isolated case studies highlight the need for additional perception, knowledge, and preparedness surveys of at-risk populations to assist in developing and implementing effective education efforts, particularly in communities that are threatened by near-field tsunamis because of the lack of adequate warning time. The committee commends the NTHMP for citing the need for evaluations and surveys to determine the effectiveness of tsunami education products and the level of preparedness of at-risk populations in its draft 2009-2013 strategic plan. The committee encourages the NTHMP to focus future preparedness assessments on communities threatened by near-field tsunamis, where successful evacuations will be more the result of a well-informed population taking self-protective actions and less from official response procedures.

Conclusion: For far-field tsunamis, successful evacuations will depend on at-risk individuals understanding official warnings and following instructions given by local agencies. For near-field tsunamis, successful evacuations will depend on the ability of at-risk individuals to recognize natural cues and to take self-protective action. The committee concludes that previous knowledge gained through sustained education efforts will likely play a larger role in saving lives from near-field tsunamis than warnings issued by the tsunami warning centers, given the current scientific and technological constraints on issuing warnings fast enough. Regardless of the kind of tsunami, understanding the needs and abilities of at-risk populations is a critical element in developing effective education. Although numerous isolated studies have been conducted in coastal communities, the NTHMP has not systematically assessed the perception, knowledge, and levels of preparedness of at-risk individuals. Lacking this information, the NTHMP has limited baseline information from which to gauge the effectiveness of education efforts, to tailor future efforts to local needs, or to prioritize limited funds.

Recommendation: Faced with limited resources, the NTHMP should give priority to systematic, coordinated perception and preparedness studies of communities with near-

field tsunami sources, in order to discover whether at-risk individuals are able to recognize natural cues of tsunamis and to take self-protective actions. Consistent, evidence-based approaches from the social and behavioral sciences should be used in the various study areas to allow the NTHMP to compare communities and prioritize future education efforts and resources.

Increasing the Effectiveness of Public Education of Tsunamis

Although tasked to review the availability and adequacy of tsunami education and out-reach for children, adults, and tourists, the committee discovered it could not fully comment on

|

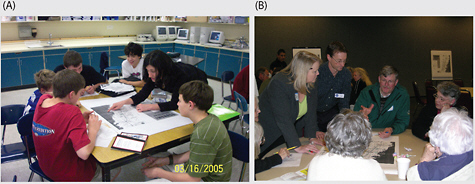

a pilot tsunami awareness program in 2004 (above figure; Connor, 2005). The goal was to develop a comprehensive tsunami outreach program that reached various segments of the community through multiple channels and outreach types. Baseline measurements followed by post-outreach assessments were integral to gauging the influence of outreach efforts on public knowledge of and capacity to respond to future tsunamis. The outreach efforts were managed by a tsunami outreach coordinator, made possible with NTHMP funding, and were primarily driven by the involvement of more than 50 volunteers, including local students, retired residents, and officials. The tsunami awareness program was based on five outreach strategies designed to reach target audiences and provide multiple channels for learning: a neighborhood educator project had volunteers going door to door to discuss tsunami issues with homeowners; a business workshop focused on improving the business community’s emergency plan and preparedness planning; a school outreach program educated elementary-school children through auditorium-style presentation and activities and middle-school youth through small-group discussions; a public workshop was geared for involving the community and tourists in discussing tsunami preparedness; and a tsunami-evacuation drill was run at the end of the outreach program as a chance for individuals to practice what they had learned. Surveys were conducted before and after the various outreach strategies to determine their influence on public understanding of tsunamis and their preparedness to future events. Post-outreach surveys indicate that 68 percent of Seaside households received information and more than 2,200 people participated in outreach events. The surveys documented measurable differences in tsunami knowledge and preparedness of Seaside community members because of the various outreach efforts. The project demonstrated that each of the five strategies served a different role to fully prepare the community and create a culture of awareness. Project organizers concluded that program success was largely due to the “people-to-people, face-to-face discussions” at each event. An important next step is to see if and how these lessons could be transferred to larger communities (e.g., Los Angeles, Honolulu) where social networks are more complicated and the magnitude of people in tsunami hazards is much greater. |

this topic for several reasons. One obstacle to this task is that the true breadth of U.S. tsunami education efforts is not currently known by the NTHMP. There is no existing compilation or inventory of NTHMP-related tsunami education efforts, nor is there a physical or electronic repository for aggregating education efforts. Lacking an existing compilation or national assessment of tsunami education efforts, the committee compiled a list of efforts that demonstrates the breadth of activity across the NTHMP and outside of the program (Appendix E). Based on this incomplete list of examples, it is clear that tsunami education is being done by various organizations (e.g., county and state emergency management departments, K-12 educators, International Tsunami Information Center (ITIC), Pacific Tsunami Museum, United Nations, nonprofit organizations) in various ways (e.g., coloring books, DVDs, fairs, school curriculum,

brochures, business planning guides, media kits, websites, museums, online games, newsletters, workshops) to various audiences (e.g., children, adults, households, business owners, officials, tourists) and at various scales (e.g., villages, unincorporated towns, cities, counties, states).

The committee commends all those involved in tsunami education for their individual efforts to raise tsunami awareness in coastal communities. However, the lack of NTHMP mechanisms to systematically compile, evaluate, and disseminate these efforts at a national scale breeds the potential for the duplication of efforts and for conflicting messages. For example, the committee found that several states (e.g., Hawaii, Oregon, Washington) are developing their own tsunami education guidelines (often referred to as “train the trainer” workshops) with little communication among the parties and uneven application of evidence-based approaches.

With regard to new education efforts, a web-based repository for tsunami education material is a vital first step for avoiding duplication of efforts, transferring lessons learned and best practices, and identifying gaps in education coverage. Duplication of efforts could be reduced if education efforts were conducted involving several NTHMP members to develop common tsunami education materials for certain sectors (e.g., broadcasters, hotel owners, tourists, households, and schoolchildren). Local differences can be added to education materials to reflect local needs, but a core set of materials with national relevance could be developed and maintained by the NTHMP to ensure a more consistent message, which—as previously noted—increases the effectiveness of educational efforts.

A second obstacle that prevents the committee from fully commenting on the status of tsunami education is the lack of tsunami education programs that explicitly included pre- and post-outreach evaluations of effectiveness, such as the evaluation associated with a series of tsunami outreach efforts in 2005 in Seaside, Oregon (see Box 3.3). Because there are few studies that have documented the perceptions, knowledge, and capacity to prepare at-risk populations, there is no consistent baseline from which to gauge the effectiveness of education programs. That an education effort occurred could be confirmed, but there is no information on whether the knowledge of participants increased because of an effort.

Besides lacking education evaluations, the NTHMP also lacks standards and criteria for evaluating the multitude of tsunami education efforts occurring in member states, territories, and commonwealths with regard to their information content, dissemination process, presentation style, and enculturation of new information. For example, tsunami education products have not been evaluated for the level at which they discuss tsunami hazards, the vulnerability of individuals and communities to tsunamis, how at-risk populations can reduce their vulnerability, and how people should act if a tsunami occurs. A national tsunami research plan (Bernard et al., 2007) also notes that there has been little analysis on the effectiveness of education programs or coordination among states to define messages with desired outcomes. Having consistent evaluation criteria is critical if the NTHMP is to evaluate isolated education efforts and to determine funding priorities for future education programs, in terms of location (e.g., Alaska versus Puerto Rico) and focus (e.g., tourists versus residents).

The need for measurable outcomes and standards for educational programs was also noted in the NTHMP five-year review (National Tsunami Hazard Mitigation Program, 2007) and the 2007 national tsunami research plan (Bernard et al., 2007). Currently, school curricula

are evaluated for their compliance with education standards (e.g., National Research Council, 1996b), but other tsunami outreach efforts (e.g., workshops, media kits, hotel training guides) do not undergo any formal evaluative review by the NTHMP. This committee commends the NTHMP for recognizing these and other deficiencies in tsunami education in its 2009-2013 draft strategic plan. The plan cites several performance measures related to tsunami education. Such performance measures include an inventory of current efforts, an education implementation plan, and electronically available curricula by 2009 (which has not been met). Goals for 2010 include guidelines for tsunami education and a national tsunami media toolkit. Further goals include outreach materials for coastal businesses and tourists, integration of tsunami information into K-12 education through at least one state pilot project by 2011, and a web-based repository for NTHMP-related products by 2012. The draft strategic plan also recognizes the need for evaluation, and it plans to conduct evaluations that determine the effectiveness of tsunami education products and programs in 10 selected communities by 2010.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Tsunami Program and the NTHMP are not alone in their mission to safeguard coastal communities from hazards. Other organizations, including other NOAA entities, also share the mission of educating communities about coastal hazards. For example, the NOAA Sea Grant College Program strategic plan (2009-2013) includes a focus area on hazard resilience in coastal communities that includes research aimed at increasing the availability and utility of hazard-related information and the development of comprehensive education programs of coastal hazards and how to prepare for them. The NOAA Office of Education’s strategic plan (2009-2029) cites a need for a NOAA education community that functions in a unified manner and coordinates with agency extension, training, outreach, and communications programs. The NOAA Coastal Services Center works with private and public sector partners to address coastal issues, such as resilience to natural hazards, and offers training and information on stakeholder involvement in local management, needs assessments, project/program evaluation, and resilience assessments. In the course of this review, the committee heard of little, if any, interaction between the NOAA Tsunami Program and other NOAA efforts devoted to coastal hazards education (e.g., NOAA Office of Education, NOAA Sea Grant College Program, NOAA Coastal Services Center). The committee found no evidence that TWC staff interact with staff at other NOAA warning centers (e.g., National Severe Storms Laboratory [NSSL], National Hurricane Center [NHC], Aviation Weather Center [AWC], Storm Prediction Center [SPC]), representing missed opportunities to learn best practices in educating the public about extreme events and warning messaging.

Conclusion: Current tsunami education efforts are not sufficiently coordinated and run the danger of communicating inconsistent and potentially confusing messages. The committee was not able to fully evaluate the effectiveness of current educational efforts because the NTHMP lacks an inventory of education efforts or evaluative metrics. The committee concludes that current tsunami education efforts of each NTHMP member are conducted in an ad-hoc, isolated, and often redundant nature and without regard to evidence-based approaches in the social and behavioral sciences on what constitutes effective public risk education and preparedness training. The lack of NTHMP mechanisms

to systematically compile, evaluate, and disseminate these efforts at a national scale breeds the potential for the duplication of efforts and for conflicting messages. There is little evidence that the NOAA Tsunami Program or the NTHMP are leveraging the education efforts and expertise of other NOAA entities that also focus on coastal hazards, extreme events, and warning messaging.

Recommendation: To increase the effectiveness of tsunami education, the NTHMP should do the following:

-

Develop consistent education efforts among its members using evidence-based approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. The goal of this education should be to teach at-risk people to correctly interpret natural cues and understand official warnings, to motivate them to appropriately prepare for tsunamis evacuations, and to make that knowledge and motivation a permanent part of the local culture.

-

Tailor tsunami education to local circumstances and the specific needs and abilities of at-risk individuals in a community, including tourists.

-

Create and maintain an online repository of education efforts.

-

Develop and implement a program to evaluate the effectiveness of education efforts and use conclusions from evaluations to make education programs even more effective.

-

Leverage the hazard education efforts and expertise of other agencies and NOAA offices.

COMMUNITY PREPAREDNESS EFFORTS

While tsunami detection and warning messages are the responsibility of the federal tsunami program, local and state officials are responsible for preparing communities for future tsunamis, issuing evacuation orders, and managing evacuations and response efforts. Community preparedness and emergency management of tsunamis are largely the responsibility of county emergency managers. Other agencies and organizations play roles as well, including K-12 educators, land-use and building regulatory agencies (e.g., location and type of construction, inspection of construction, and mitigation/abatement of existing hazards), health and social services agencies (e.g., post-disaster care and sheltering, care for special-needs populations), economic-development agencies (e.g., business continuity planning, post-disaster loans), and multi-department working groups (e.g., post-disaster community recovery planning). Because of the significant breadth and depth of actions that can be implemented by various actors to prepare communities for tsunamis, the committee restricted its review of community tsunami preparedness to the NOAA TsunamiReady program. This program is considered by NOAA to be the primary vehicle for preparing communities for future tsunamis.

The NOAA TsunamiReady program is modeled after the National Weather Service (NWS), StormReady program and its objective is to help communities reduce the potential for

tsunami-related disasters through redundant and reliable warning communications, public readiness through community education, and official readiness through formal planning and exercises. Jurisdictions (e.g., cities, counties, or states) are recognized after they submit an application to the NOAA NWS and a local TsunamiReady Advisory Board verifies information in the application. Since the NTHMP approved the implementation of the TsunamiReady program in 2001, it has been constantly under review to increase its ability to effectively measure and take into account the goals and objectives of the NTHMP. Draft TsunamiReady criteria currently being discussed within the NTHMP broaden the emergency management scope of the original criteria and include aspects of mitigation through land-use planning and regulation; promulgation of inundation maps and their use in public education; alert and warning systems to notify the public of potential dangers; training emergency response and management staff in the nature of tsunami impacts and their roles and responsibilities in public notification, response, and recovery; and sustained education on evacuation procedures, routes, and refuge areas.

Based on the committee’s discussion with representatives from the NOAA Tsunami Program, the TsunamiReady Program, the emergency management community, and a review of the original and new draft standards of the TsunamiReady Program (draft November 2008), the committee observed the following:

Standards. The TsunamiReady program lacks a professional standard (such as NFPA 1600 or the Emergency Management Accreditation Program) regarding what actually constitutes tsunami readiness and how success would be evaluated. The new, draft criteria for TsunamiReady include an extensive list of possible actions, but local officials have no guidance on which actions are most effective and how to prioritize the various actions. The actions taken during a tsunami on June 13, 2005, in Crescent City (see Box 3.4 and Table 3.1) illustrate how current standards might not result in sufficient community readiness. There is no current national database of actions taken by each TsunamiReady community; therefore, it is not possible to identify best practices, lessons learned, or additional needs in community resilience. Maintaining an electronic database of TsunamiReady applications, for communities new to the program and for those seeking re-certification, would provide the NTHMP with the ability to conduct annual needs assessments across the nation and to identify where additional efforts may be warranted.

Accountability for standards. The practice of local committees (led by a local Warning Coordination Meteorologist) to verify that communities have met program standards allows communities to implement a flexible program but requires a level of accountability to be maintained by the national program. In the course of our review, the committee observed situations in which communities are not satisfying mandatory criteria (e.g., hazard or evacuation signage) but are still recognized as TsunamiReady communities. The current metric for the TsunamiReady program is the number of communities that are annually recognized, yet if mandatory criteria are being ignored in the recognition process, the effectiveness of the program and its success criteria are questionable. Some states (e.g., Washington) have recognized the issue of accountability and now require state emergency management agency approval of TsunamiReady applications before a community is recognized.

|

BOX 3.4 Evaluation of a TsunamiReady Community’s Response to a Tsunami The primary missions of the TsunamiReady program are to educate at-risk individuals on what to do when a tsunami warning is issued and to mitigate, if possible, potential losses. Evaluating the effectiveness of the program is difficult, given the infrequency of tsunami warnings. Therefore, as a case study to provide insight on the program (as opposed to a full evaluation), the committee reviewed the actions taken in the community of Crescent City, California, a recognized TsunamiReady community during two tsunami events—the June 14, 2005, tsunami (which originated offshore Crescent City within the Gorda Plate) and the November 15, 2006, tsunami (which originated in Russia’s Kuril Islands) (based on a California Emergency Management Agency [CalEMA] internal action report). Both events illustrate the limited effectiveness and challenges of the current TsunamiReady program. Crescent City was no stranger to tsunamis when it received warnings in 2005 and 2006. The1964 Good Friday earthquake and tsunami in Alaska inundated Crescent City harbor and parts of its business district, resulting in extensive damage and the loss of lives. After the 1991 Petrolia, California, earthquake, a focused study of tsunami potential and preparedness centered in Humboldt and Del Norte Counties, where Crescent City is located. Extensive media coverage of the earthquake and tsunami threat resulted in funding a public education and preparedness campaign and developing an earthquake/tsunami scenario to support state and local emergency planning efforts. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) provided funding to prepare public information brochures and to make improvements to the local siren warning systems. The designation of Crescent City as TsunamiReady was a direct result of the heightened awareness and commitment of the community in preparing for a tsunami. Observations of the 2005 and 2006 tsunami events suggest the community has more work to do with regard to community education and mitigation (Table 3.1). During the 2005 event, there were spontaneous car-based evacuations by the public into areas of potential inundation, and some overwhelmed dispatch offices failed to follow notification procedures. In 2006, alert and warning procedures were followed, but extensive damage was incurred because of deferred maintenance of port facilities. Despite its TsunamiReady recognition, the community observed significant weaknesses in its ability to effectively respond to tsunamis during the 2005 and 2006 tsunamis. As is likely the case in all communities, sustaining public awareness and maintaining this knowledge of evacuation procedures is a significant challenge for local officials. |

Effectiveness. There are no assessments of the effectiveness of the prescriptive readiness actions, the sustainability of the readiness capabilities at the local level, or whether mitigation actions reduce exposure to losses. The program does not identify baselines against which to assess progress other than a count of the number of recognized communities. Additionally, there has not been an assessment of how TsunamiReady communities have performed in actual events or if the criteria used in the program relate to performance.

TABLE 3.1 Actions During Tsunami Events on June 14, 2005, and November 15, 2006

|

|

Event |

Prescribed Action |

Actual Response |

|

June 14, 2005 |

Felt earthquake |

Evacuation on foot to high ground along prescribed evacuation routes |

Spontaneous evacuation of population, in vehicles, on routes into areas of potential inundation |

|

June 14, 2005 |

Notification of tsunami warning |

Public safety dispatch to activate sirens and provide notification |

Dispatch was overwhelmed by 911 calls and failed to follow activation/ notification procedures |

|

June 14, 2005 |

Verification of notification by state |

Public safety dispatch to receive call and verify receipt of warning |

Dispatch could not answer calls from state authorities |

|

November 15, 2006 |

Distant earthquake and tsunami warning issued by west Coast/ Alaska Tsunami Warning Center (WC/ATWC) |

Notification and cancellation of warning by WC/ATWC, based on updated information from Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis (DART) buoy data and projections from Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory (PMEL) model |

Alert and warning procedures followed. Extensive damage occurred in the Crescent City marina where deferred maintenance resulted in structural deterioration of dock facilities |

|

SOURCE: Committee member, based on CalEMA internal action report. |

|||

Entities. TsunamiReady Program recognition currently can only be given to legally recognized jurisdictions (e.g., states, counties, tribes), excluding other entities such as unincorporated communities. Previous studies have shown that significant percentages of individuals living in tsunami-prone areas are in unincorporated villages (Wood, 2007; Wood et al., 2008).

Training. NWS Warning Coordination Meteorologists (WCMs) are the designated local points of contact and advocates for the TsunamiReady Program. Proposed TsunamiReady standards seek to frame the program as an effort to increase community resilience, yet WCMs are trained meteorologists and receive little technical training in preparedness, emergency management, education, planning, and risk. Although NOAA is currently working on a training course with the WC/ATWC to inform WCMs on center operations, it is not apparent that WCMs are receiving training in mitigation, education, or other approaches to build resilience that are now being touted as the new direction of TsunamiReady.

Resources. The TsunamiReady Program objective to encourage tsunami resilience of all coastal communities in our nation is commendable, but the program has access to few resources and little staff time to accomplish this objective. As a result, the TsunamiReady Program at the

national and local level becomes an additional duty of a WCM instead of the primary duty of a scientist trained in emergency management or community resilience. The situation has been exacerbated with the addition of Atlantic and Caribbean communities without an increase in overall program budgets.

Public education. The committee found that the current education criteria of inventorying the number of annual tsunami awareness programs is vague and lacks specific guidance on the target audience (e.g., residents, employees, tourists) and on how to accomplish goals. Proposed standards for outreach include a commendable list of potential activities, such as incorporating materials into public utility bills or providing tsunami safety training to local hotel staff. However, jurisdictions can meet the mandatory criteria for outreach by implementing just “one or more” of the several potential activities. Therefore, a jurisdiction could technically meet the outreach criteria simply by passively posting tsunami information on an agency website and ignoring more active efforts, such as training local hotel staff and working with faith-based and civic organizations.

Incorporation of Social Science. The TsunamiReady Program currently lacks involvement from researchers trained in the social sciences, land-use planning, and emergency management. The NOAA Tsunami Program needs to be more proactive in incorporating social science findings in program deliberations, evaluation, and criteria development.

During deliberations about the TsunamiReady Program, the committee compared TsunamiReady to other approaches to improving community preparedness to natural hazards. The Emergency Management Accreditation Program (EMAP)2 is one such program that also aims to mitigate the risk from natural hazards, but unlike TsunamiReady, EMAP is more broadly geared toward all-hazards mitigation. EMAP is the nationally recognized standard for emergency management and establishes “a common set of criteria for disaster management, emergency management, and business continuity programs … (and) provides criteria to assess current programs or to develop, implement and maintain a program to mitigate, prepare for, respond to and recovery from disasters and emergencies.”3 Standards are established by the EMAP Standards Committee in a process complying with procedures and processes as prescribed by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI). Compliance with the standard is voluntary, and assessments and accreditation are applied through a review process conducted by peers from the emergency management profession.

Although the most current TsunamiReady draft (November 6, 2008) includes many elements of the above EMAP standards (http://www.emaponline.org/), it is currently a mix of requirements that are not well structured. At the time this report was written, the draft

|

2 |

Supported by FEMA, National Emergency Management Association (NEMA), International Association of Emergency Managers (IAEM), Council of State Governments (CSG), National Association of Governors (NCG), National League of Cities (NLC), National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs (OJP), and U.S. Department of Transportation. EMAP is managed by the CSG and is overseen by an appointed commission. http://www.emaponline.org/. |

|

3 |

EMAP Standard, April 2006, |

TsunamiReady community requirements do not fit within the concept, terminology, and format of a standard, but they would more appropriately be described as a detailed assessment scorecard for rating a local government. EMAP provides a concept and structure that could serve as a model for TsunamiReady. The documentation and costs of EMAP assessments and accreditation may preclude its application below the level of state emergency management agencies, but the process of developing standards, use of baseline assessments, peer review, periodic assessment of program sustainability, and continuous improvement of both programs and standards could be a model for the TsunamiReady Program. Alternatively, the NOAA Tsunami Program could simply encourage larger jurisdictions to become accredited through EMAP, with the requirement that tsunami events be part of the multi-hazard plan. The NTHMP, through EMAP, could initiate an ANSI-compliant standard development process, within which the existing scorecard would be restructured and simplified. At a minimum, the NTHMP could consider the five elements of EMAP as mandatory requirements, in addition to a public education requirement based on the latest social science on hazard education: (1) hazard identification, risk assessment, and consequence analysis; (2) a mitigation program to reduce structural vulnerability in areas subject to tsunami inundation; (3) emergency operations, recovery, and continuity of operations plans and procedures; (4) redundant communication systems capable of communicating alerts; and (5) training of officials and responders, exercises, program evaluations, and development of corrective action plans.

Conclusion: The primary mechanism for increasing community preparedness for tsunamis in the United States is the NOAA TsunamiReady Program. The current success metric for the program is the number of communities that are annually recognized. The committee questions the effectiveness of the program and its success criteria because the program lacks the following elements: (1) a professional standard to guide its development, (2) metrics to assess baseline readiness and community needs, (3) evaluative criteria to assess community performance during a tsunami, (4) accountability measures to ensure recognized communities meet mandatory requirements, (5) local points of contact with training in community preparedness, and (6) criteria and guidance on what constitutes effective public outreach and preparedness efforts. Although signage is considered mandatory under TsunamiReady, the use of tsunami signs is inconsistent among NTHMP members, suggesting the need for greater TsunamiReady program accountability and likely creating the incorrect impression that areas without signage are not tsunami hazard zones.

Recommendation: The NOAA Tsunami Program should strengthen the TsunamiReady Program by making the following changes:

-

Implement professional and modern emergency management standards following the example of EMAP.

-

Develop evaluative criteria for the assessment of community performance during actual tsunamis.

-

Increase the level of accountability required of communities in order to maintain their TsunamiReady status.

-

Increase program transparency by creating a publicly accessible, digital database of actions taken by TsunamiReady communities.

-

Conduct baseline assessments of readiness for all at-risk communities.

-

Rate communities on several levels of readiness rather than a simple ready-or-not status.

-

Have local points of contact who are trained in risk communication regarding public warning messaging and public warning dissemination, emergency management, and community preparedness.

-

Develop guidelines as to what constitutes effective public outreach, make these guidelines publicly available, and regularly evaluate public outreach efforts.

-

Ensure that program criteria are evidence-based by including social scientists in the development of the criteria.

-

Provide guidance to states and local communities on state-of-the-art preparedness plans that elicit appropriate public protective actions.

The committee believes that many of these recommendations can be accomplished if the NOAA Tsunami Program folded the TsunamiReady Program into the all-hazard Emergency Management Accreditation Program, instead of continuing to maintain its own, separate recognition program.

DEVELOPING AND DELIVERING EFFECTIVE WARNING MESSAGES

Long-term education and community preparedness efforts set the stage for changing the behavior of at-risk individuals and, in the case of near-field tsunamis, may be the only guidance people receive to help them evacuate. However, the likelihood of individuals evacuating tsunami-prone areas is also influenced by the official warning message they receive from the tsunami warning centers and from local and state emergency management agencies. To be effective, these messages need to (1) contain the necessary information that leads individuals to take appropriate protective action, and (2) reach at-risk people in a timely fashion. This section reviews progress in developing and delivering effective warning messages that motivate individuals to take protective action. Topics discussed below represent active fields of research across all hazards, and the tsunami community can draw from lessons learned particularly in the severe weather (e.g., Weather and Society*Integrated Studies (WAS*IS); http://www.sip.ucar.edu/wasis/) or the earthquake community.

Developing Effective Messages

Because some people believe disasters will not happen in the near future and will happen to someone else, warning messages need to first overcome people’s natural belief in their own safety and then guide them to take protective actions that are inconsistent with their perception of safety (Slovic et al., 1980; Burningham et al., 2008). An effective warning message

provides content about what to do using language that allows a person to visualize the response (e.g., “Climb the nearest slopes until you are higher than the tallest buildings” instead of “Evacuate to higher ground”). It also informs people when they should start and complete the recommended protective action, which groups are in harm’s way and must take action, and how protective actions will reduce pending consequences of inaction. Effective warning message style is simply worded, precise, authoritative, and non-ambiguous, even when discussing uncertainty in forecasts (e.g., “We cannot know exactly how high the tsunami will be when it reaches our shores, but all experts agree that it is likely high enough that everyone should evacuate now”). Accurate messages are critical because information errors confuse people and affect their response to a pending disaster. Consistent messages (both consistent internally and across messages from different sources) are needed to reduce the public’s choices regarding risk. The protective action to be taken and changes from previous messages need to be clearly explained (Mileti and Sorensen, 1990).

To date, the committee is not aware of any previous efforts to formally review the messages from the TWCs relative to evidenced-based approaches from the social and behavioral sciences. The current and future warning messages of both the TWCs and the NWS would both benefit from review and improvements based on the latest social and behavioral sciences about how and why such messages influence the behavior of people at risk and from being rendered consistent with this knowledge base.

The committee reviewed the standard messages that are composed and delivered by the TWCs and observed that several of the principles for effective warning-message content and style have not been followed. For example, the information statement issued at 12:57AM on February 27, 2010 (see Box 3.5), does not clearly identify who needs to take action because it describes the affected area twice using different descriptions (listing individual West Coast states by name once and then referring to the U.S. West Coast once). Although most informational statements of the WC/ATWC were issued when the earthquake was too small to generate a tsunami, this statement was more like a preliminary statement that at the end said to stay tuned for more. The message was also ambiguous and internally inconsistent—it stated “A tsunami is not expected” at one point and then later stated “A tsunami has been generated that could potentially impact the U.S. West Coast/British Columbia and Alaska.” Recommended actions for states to take were largely absent in this message, except for the last sentence, which encouraged people to see the warning center website. A true warning message includes required next steps; therefore, this message was more of an alert of a physical process.

With regard to providing recommendations for required actions, the committee recognizes the limitations placed on the TWCs. Because of existing laws, the TWCs, as part of the federal government, cannot order evacuations. Therefore, unless new national policies are implemented, the TWCs are limited to what they can say for recommended next steps and official warning messages will continue to lack specificity with regard to what protective actions need to be taken. Agreements have been made in certain states (Hawaii and Washington) where warning messages issued by the TWCs can automatically trigger sirens, but only in cases where tsunamis are expected to arrive within minutes of generation. In all other cases, however, it is the responsibility of county emergency managers, in close consultation with state emergency managers,

|

BOX 3.5 Example of a Message from a Tsunami Warning Center WC/ATWC Information Statement – TW WEAK53 PAAQ 270857 TIBAK1 PUBLIC TSUNAMI INFORMATION STATEMENT NUMBER 3 NWS WEST COAST/ALASKA TSUNAMI WARNING CENTER PALMER AK 1257 AM PST SAT FEB 27 2010 …A STRONG EARTHQUAKE HAS OCCURRED BUT A TSUNAMI IS NOT EXPECTED ALONG THE CALIFORNIA/ OREGON/ WASHINGTON/ BRITISH COLUMBIA OR ALASKA COASTS… NO WARNING…NO WATCH AND NO ADVISORY IS IN EFFECT FOR THESE AREAS. A TSUNAMI HAS BEEN GENERATED THAT COULD POTENTIALLY IMPACT THE U.S. WEST COAST/ BRITISH COLUMBIA AND ALASKA. THE WEST COAST/ALASKA TSUNAMI WARNING CENTER IS INVESTIGATING THE EVENT TO DETERMINE THE LEVEL OF DANGER. MORE INFORMATION WILL BE ISSUED AS IT BECOMES AVAILABLE. A TSUNAMI HAS BEEN OBSERVED AT THE FOLLOWING SITES |

to issue evacuation orders based on the messages released by the TWCs. Given the separation in responsibilities and authorities, close coordination between the TWCs, states, and local jurisdictions is needed to ensure that the public receives information about the threat and proper protective action (see the section on interagency coordination for more discussion). Observations during the 2010 Chilean event suggest that confusion still exists among the public about actions to take in response to the TWC messages (Wilson et al., 2010). Initial observations of the warning messages issued related to the 2010 Chilean earthquake and tsunami suggest that California jurisdictions did not have a consistent understanding of lines of communication, what an “advisory” alert level means in terms of recommended next steps, or who should be involved in taking next steps (Wilson et al., 2010).

The committee also found inconsistencies between the warning products of the TWCs and those of the NWS. For example, the NWS issues a “watch” for an event that has an 80 percent chance of becoming a warning, but this is not the case with the TWCs whose watches rarely

become warnings. Another current inconsistency is how the TWCs and the NWS deal with “all-clears.” The TWCs cancel a bulletin, which could be read by the public as a signal that it is safe to return, which is not the same as an “all-clear” issued by the NWS. The NWS will soon move from using the “alert bulletin system” to an “impact-based system,” which will introduce another inconsistency with the TWCs. An additional potential source of confusion stems from the fact that “information statements” are used for conveying two different types of messages: first to convey some initial information and the notion to stay tuned for more, and second to convey that a certain earthquake has not generated a tsunami.

Recommendation: The NOAA/NWS should remedy current differences between the TWC’s and the NWS’s warning products and ensure consistency in the future. A mechanism should be put in place so that pending and future inconsistencies are quickly identified and acted upon so that products from the TWCs and the NWS match.

Once the TWCs issue warnings, watches, or advisories, it is the responsibility of county emergency management and/or public-safety agencies to issue their own messages to individuals in tsunami-prone areas (except in the case of near-field tsunamis where evacuations will be spontaneous and local agencies will have to react to, and instead of lead, the evacuations). In many cases, after the TWCs issue their messages, county and state agencies discuss the situation and potential strategies with the TWCs through teleconferences. Following these conversations, individual jurisdictions will then make their own decisions regarding whether to evacuate tsunami-prone areas or not. Pre-event tsunami education of local public-safety officers is important because their knowledge of tsunami threats, the vulnerability of local populations, and the time and logistics required to evacuate these populations all play a factor in the evacuation decision making process.

Disparities in knowledge and risk tolerance at the local level can lead to different decisions. Although the TWCs are releasing information to an entire region (e.g., the Cascadia subduction zone from northern California to Washington), individual county jurisdictions will decide how to use this information in their own warning messages sent to people along their coasts. In the response to the warning messages released during the June 14, 2005, event, there were cases where adjacent counties in Oregon received the same information from the TWCs and yet made different decisions. One county called for an evacuation, while the adjacent county did not. To the public, these disparities in response are inconsistent and create confusion.

Effective Delivery of Warning Messages

Actions taken by the public are influenced by the warning delivery method because of the time it takes people to convert pre-warning perceptions of safety into current perceptions of risk. The frequency of warning-message communications and the increasing number and types of communication channels are shown to positively impact people’s warning response. There is no one single credible source of information, because various groups attach credibility to different spokespeople, perceptions of credibility change with time, and credibility and warning message belief are not identical. Consequently, it is vital to create diverse sources of public warnings, an effort that requires pre-event emergency planning and agreement from many partners to disseminate the same warning message long before an event occurs.

Effective dissemination of warnings involves multiple organizations using multiple channels to frequently deliver the same message. Both TWCs disseminate their messages over multiple channels, such as the National Warning System (NAWAS), State Warning Systems (e.g., Hawaii Warning System (HAWAS), California Warning System (CALWAS)), the Global Telecommunications Service (GTS), the NOAA Weather Wire, the Aeronautical Fixed Telecommunications Network, the military-related Gateguard circuit, emails, faxes and telex, and phone calls (among others). With two warning centers sending messages over multiple channels, it is most important that messages be consistent in order to minimize confusion by the public. However, because the TWCs have different areas of responsibility (AORs), warning messages from the two centers are designed for different audiences and contain different information (see more

discussion on this AOR issue in Chapter 5). Although these messages are not intended for public consumption (Paul Whitmore, NOAA, personal communication), products from both TWCs are distributed to members of the public and the media who have signed up on the TWCs’ websites to receive these alerts. Consequently, the messages are immediately disseminated to the public via television, radio, and the Internet—as was the case during the 2009 Samoan tsunami (Appendix I) and the 2010 Chilean tsunami (Appendix J).

The generation of two sets of warnings, although technically appropriate due to different areas of responsibilities, can be a major source of confusion among the emergency management community and the public, as illustrated by the June 14, 2005, event (Appendix F). During the 2005 event, media outlets in the Pacific Northwest received messages from both TWCs that appeared to contradict each other because the distinction between areas of responsibility was not well understood. It is likely that media outlets and the public will continue to misunderstand this jurisdictional distinction in future warnings. Therefore, it is central to the success of the TWCs that they further improve the consistency and clarity between their messages to prevent any confusion resulting from the distinct AOR. Alternatively, the issuance of a single message after internal consultation between the TWCs could definitively eliminate the potential for confusion from differences in message content.

Local officials will receive warning messages from the TWCs typically within five minutes of an event. Information will come via the NAWAS to the state warning centers and via state versions of the warning system (e.g., HAWAS) to county Public Safety Access Points (PSAPs or 911 dispatch) if a warning has been issued. If the jurisdiction is an incorporated municipality, warning messages are sent from the PSAP and law enforcement teletype to the local dispatch. If local officials are directly linked to seismic network displays (e.g., the California Integrated Seismic Network (CISN)), then they will receive confirmation of the earthquake via both ShakeMap4 and TWC documentation. Once local officials decide to issue an evacuation order, they will issue it via pre-determined channels (e.g., sirens, AHAB (All-Hazard Alert Broadcast), reverse-911 calls, etc.).

It is important to note that current dissemination routes and plans described by the TWCs and local emergency management resemble the old paradigm of a linear message pathway from the warning center to the local emergency officials, who then notify the public and order an evacuation. Such a linear information transfer can no longer be assumed with the rise of the Internet and other telecommunications technology. Instead, communication networks resemble a web of sources with information coming from multiple systems, both official (e.g., local sheriff, NOAA Weather Radio (NWR)) and unofficial (e.g., TV, Internet, friends). As mentioned earlier, the media and many members of the general public now receive alerts directly from the TWCs, thereby removing local emergency management from the communication path.

Another factor likely to change warning messaging is mobile social networking technology (e.g., Twitter, Facebook, and Google Maps). These technologies have all been harnessed

through grassroots efforts to disseminate frequent updates on personal safety and relief support after a disaster, such as the 2007 San Diego wildfires and the 2008 Virginia Tech University shootings (Hughes et al., 2008; Winerman, 2009) and hold great promise in complementing current warning dissemination methods for communities threatened by both near- and far-field tsunamis. For at-risk individuals who may only have minutes to escape tsunami-prone areas, being warned by social networking technology used by other people in tsunami hazard zones may be a more realistic and timely way to quickly disseminate information than traditional message-dissemination paths. The number of people using these technologies will surely grow in the future, and their applications to disaster warnings and response efforts will be more prevalent.

The use and role of social networking and mobile technologies in emergency, crisis, and disaster management is an active research area (International Community in Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, 2008, 2009). A persistent concern about their use is the potential for inconsistent information that promotes confusion, and additional research is needed to contend with this problem. The future of tsunami warning likely involves a concerted effort by local, state, and federal agencies to integrate and leverage social networking technologies with the current message dissemination methods. Public agencies and officials with disaster warning and response duties could also monitor the spread of social networking technologies in coastal communities threatened by near-field tsunamis. Unofficial messages from these social networks could confirm official warnings, minimizing the amount of time people typically take for the warning confirmation process and before they evacuate (Mileti and Sorenson, 1990; International Community in Information Systems for Crisis Response and Management, 2008, 2009). Collaborative web-based tools (e.g., chat rooms, blogs, wikis, instant messaging) could assist in maintaining situational awareness and clarify concerns at the state or local level.

Although social networking technology holds great promise in supporting near-field tsunami evacuations, the technology is not currently embraced by many local or federal officials. The incorporation of social networking technologies into official emergency response efforts may be difficult as federal and local disaster response agencies operate under the Incident Command System—a standardized protocol that includes a top-down chain of command for information flow (Winerman, 2009). The committee reviewed a draft white paper from the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center (PTWC) on the topic of the use of social networking and is encouraged that the TWCs are at least considering such new technologies. Although there is evidence of the TWCs investigating the potential use of collaborative information technologies with emergency managers, the committee saw little evidence that they were also embracing mobile social networking technologies that empower the general public to warn each other.

Conclusion: Messages from the two tsunami warning centers do not completely follow evidence-based approaches in format, content, and style of effective messages. The generation of two different TWC warning messages to accommodate different areas of responsibility has created confusion among the media and the general public and will likely continue to do so. Little formal attention has been paid to the use of traditional, non-

traditional, or next generation technologies (e.g., mobile and social networking) in support of community outreach and dissemination.

Recommendation: The NWS should establish a committee of experts in the social science of warning messaging to review the format, content, delivery channels, and style of TWC messages. If distinct messages are to be produced by the two TWCs, then the messages should be consistent. Ideally, the committee recommends that one message be released by the two TWCs that internally covers information for all areas of responsibilities.

IMPROVING COORDINATION OF PREPAREDNESS NEEDS AND EVACUATION PROCEDURES

Because tsunami evacuations involve multiple actors (e.g., the at-risk individual, TWCs, media outlets, critical facilities, schools, and local, state, and federal officials), significant pre-event planning, coordination, and testing of procedures are necessary to increase the likelihood that evacuations are successful. As the June 14, 2005, tsunami warning case study demonstrates (Appendix F), warning dissemination and coordination of responses is not trivial. The next section discusses efforts to ensure effective communication within the NTHMP and to test interagency coordination in the event of a tsunami.

Improving Communication Among TWCs and NTHMP Members

Because the TWCs can only provide the public with alerts about the hazard and local officials are responsible for the public response (e.g., issue evacuation orders and facilitate the evacuation), the TWCs need to establish and maintain partnerships with agencies responsible for managing evacuations. Because information flow is no longer linear or hierarchical (i.e., TWC to emergency manager to public), the TWCs need to consider not only emergency managers, but also the media and the general public as an audience when refining the warning and dissemination plans. To date, the TWCs and the NTHMP have done a great deal to engage with the customers and establish community connections, including the following actions.

-

The creation of the NTHMP Tsunami Warning Coordination Subcommittee (WCS), which enables members to give input on TWC warning products and dissemination, coordinates major tsunami exercises and tsunami end-to-end tests, exchanges experiences of past events, and discussses improvements related to operational products and dissemination.

-

NAWAS is routinely tested, including communication between the TWCs, states, and local jurisdictions. The test results and issues resolved are published by the TWCs and disseminated to all stakeholders.

-

The TWCs and the NTHMP support the development of “State Alert and Warning

-