1

Introduction

A series of powerful cross-cutting trends, made more complex by the ongoing economic crisis, threatens to complicate international relations and make the exercise of U.S. statecraft more difficult. The rising demand for resources, rapid urbanization of littoral regions, the effects of climate change, the emergence of new strains of disease, and profound cultural and demographic tensions in several regions are just some of the trends whose complex interplay may spark or exacerbate future conflicts.

—U.S. Department of Defense, 2010, Quadrennial Defense Review

The February 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review notes that climate change will play a significant role in the future security environment for the United States.1 Concurrently, the United States Department of Defense (DOD) and its military services are already developing policies and plans to understand and manage the effects of climate change on military operating environments, missions, and facilities. For the Navy, the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) established Navy Task Force Climate Change (TFCC) that was charged initially with developing a road map for Navy actions in the Arctic, and then with addressing long-term Navy policy, strategy, and plans as a result of climate change.2 This National Research Council study, commissioned by the CNO and convened under the auspices of the Naval Studies Board (NSB), was tasked to provide an understanding of the national security implications of climate change for U.S. naval forces. The study’s terms of reference charge the committee to produce two reports over a 15-month period.3 The terms of reference direct that the committee in its two reports do the following:

-

Examine the potential impact on U.S. future naval operations and capabilities as a result of climate change….

-

Assess the robustness of the Department of Defense’s infrastructure for sup-

|

1 |

Secretary of Defense (Robert M. Gates). 2010. Quadrennial Defense Review, Department of Defense, Washington, D.C., February. |

|

2 |

See Vice Chief of Naval Operations (ADM Jonathan W. Greenert, USN). Memorandum 4000 Ser N09/9U103035, “Task Force Climate Change Charter,” October 30, 2009. |

|

3 |

The study’s terms of reference are provided in Appendix A. The terms of reference were formulated by the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) staff in consultation with the NSB chair and director. |

-

porting U.S. future naval operations and capabilities in the context of potential climate change impacts….

-

Determine the potential impact climate change will have on allied force operations and capabilities….

-

Examine the potential impact on U.S. future naval antisubmarine warfare operations and capabilities in the world’s oceans as a result of climate change; specifically, the technical underpinnings for projecting U.S. undersea dominance in light of the changing physical properties.

The committee’s first report, a letter report delivered to the CNO in April 2010, summarized near-term challenges and provided findings and recommendations for U.S. naval forces to address the more immediate climate-change-related challenges and planning issues.4 This report represents the committee’s final report and provides a more complete examination of issues identified in the study’s terms of reference.

ASSUMPTIONS FOR THE REPORT

The study’s terms of reference direct that this study be based on Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) assessments and other subsequent relevant literature reviewed by the committee. Therefore, the committee did not address the science of climate change or challenge the assessments on which the committee’s findings and recommendations are based. This report addresses both the immediate and the long-term climate-change-related challenges for U.S. naval forces for each of the four areas of the terms of reference and provides findings and recommendations for addressing these challenges.5 Additionally, this report identifies research and development needs for U.S. naval forces within the context of a changing climate, and it provides findings and recommendations that the committee believes will assist in reducing underlying uncertainties for naval planning and missions.

This chapter begins with an overview of climate change effects and their implications for national security. It then examines increased international activity in the Arctic as a result of climate change and the resulting implications of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) for U.S. naval forces. Following this, the chapter reviews the positioning of the U.S. naval leadership on climate change and provides a summary of additional relevant climate assessments. The chapter concludes with a discussion of risk management

|

4 |

The committee’s letter report is provided in Appendix D. |

|

5 |

For the purposes of this report, in making recommendations for naval leadership actions, the term “immediate” is defined as requiring action now through the next Program Objective Memorandum (POM) cycle, in this case POM-14; “near term” as requiring close monitoring with action anticipated to be needed within the next 10 years; and “long term” as requiring monitoring with action anticipated to be needed within 10 to 20 years. |

approaches for addressing future climate uncertainties and an overview of the remainder of the report.

CLIMATE CHANGE EFFECTS

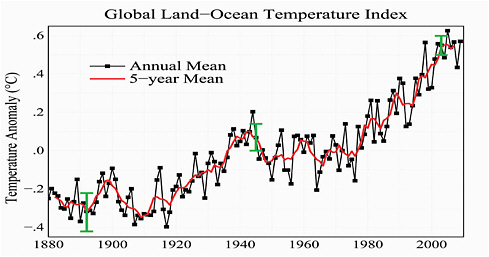

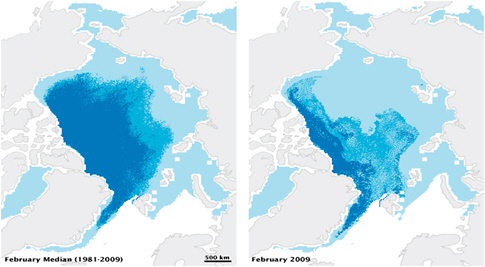

There is broad scientific consensus on many climate change topics.6 These climate certainties include measured or observed (1) higher surface, troposphere, and ocean temperatures; (2) more precipitation and drought extremes; (3) melting of mountain glaciers, Arctic sea ice, and ice sheets; and (4) a rising sea level.7 Each of the four certainties has the potential to impact U.S. naval forces’ operations and installations; if continued as projected, many will have national security implications as well. In most cases, the effects of climate change can be summarized through the effects on water—prolonged droughts, more intense storms and floods, melting ice, and/or changing ocean conditions, including ocean acidification. Many of these climate change effects and their resulting impacts are summarized in Box 1.1 and illustrated in Figures 1.1 and 1.2. In many regions of the world, the impact of climate change is likely to further exacerbate the preexisting stress on water supplies and the associated mounting pressures of population growth.8 While these issues and other potential climate change impacts are important, this report is focused through the lens of relevance and implications for U.S. naval forces.

|

6 |

For example, the National Research Council of the National Academies has recently released the first four reports from a congressionally mandated suite of studies known as America’s Climate Choices. These studies are discussed later in this chapter, and additional information is provided at the America’s Climate Choices website: http://americasclimatechoices.org/, accessed July 28, 2010. |

|

7 |

The U.S. Global Change Research Program, composed of 13 federal agencies, reported in 2009 that climate-related changes are already being observed in every region of the world, including the United States and its coastal waters. Among these physical changes are increases in heavy downpours, rising temperature and sea level, rapidly retreating glaciers, thawing permafrost, lengthening growing seasons, lengthening ice-free seasons in the oceans and on lakes and rivers, earlier snowmelt, and alterations in river flows. See Thomas R. Karl, Jerry M. Melillo, and Thomas C. Peterson, 2009, Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States, Cambridge University Press, New York, pp. 25-47. |

|

8 |

For example, Columbia University’s Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN) has compiled information from IPCC assessments, the 2005 World Bank report Natural Disaster Hotspots: A Global Risk Analysis, and CIESIN’s gridded world population data sets to present a projected geographic distribution of vulnerability in 2050. In presentations to the committee, CIESIN representatives reported that global population nearly doubled from 1968 through 2008, and that by 2048 it could grow another 40 percent, to more than 9 billion people, adding even greater stresses to water and food supplies (Robert S. Chen, Center for International Earth Science Information Network, Columbia University, “Human Dimensions of Climate Change,” and Marc Levy, Center for International Earth Science Information Network, Columbia University, “Climate Change and U.S. National Security,” presentations to the committee, November 19, 2009, Washington, D.C.). CIESIN also reported that population increases are fastest in areas most vulnerable to intense storms and flooding (e.g., coastal areas, islands, and river basins). The CIESIN analysis combines its population data sets with IPCC-projected climate-change-related vulnerabilities, economic data, and past disaster-related losses to identify areas at relative high risk from one or more hazards. |

IMPLICATIONS FOR NATIONAL SECURITY

Climate change alone is unlikely to cause conflict, but its manifestations can. The committee reviewed reports by the Center for Naval Analyses, the National Intelligence Council, and others that find that climate change can act as an accelerant of instability or conflict, placing a burden to respond on civilian institutions and militaries around the world and leading to potential national security implications.9 In addition, extreme weather events induced by a changing

FIGURE 1.1 Climate measurements indicate that Earth is getting hotter. Except for a leveling off between the 1940s and 1970s, Earth’s surface temperatures have increased since 1880. The last decade has brought the temperatures to the highest levels ever recorded. The graph shows global annual surface temperatures relative to 1951-1980 mean temperatures. As shown by the red line, long-term trends are more apparent when temperatures are averaged over a 5-year period. The hottest 14 years on record have all occurred since 1990. SOURCE: NASA/Goddard Institute for Space Studies. 2010. “Global Land-Ocean Temperature, 1880-Present,” December.

climate may lead to increased demands for defense support to civil authorities for humanitarian assistance or disaster response both within the United States and globally. Viewed from a national security standpoint, these changes would likely amplify stresses on weaker nations and generate geopolitical instability in already vulnerable regions.10

A range of military missions may result from such conditions, including the sorts of antipiracy and counterterrorism missions now being conducted in the waters off the coast of Somalia. However, the clearest implications of these changes are for humanitarian assistance/disaster relief (HA/DR) missions, which may increase in frequency, thereby potentially straining military transportation resources and the supporting force structures. The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, as a forward-deployed force, are in position to reach disaster relief sites faster than other agencies, and therefore will almost assuredly experience increased demand

|

10 |

See Statement of the Record of Dr. Thomas Fingar, Deputy Director of National Intelligence for Analysis and Chairman of the National Intelligence Council, before the Permanent Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming, House of Representatives, “National Intelligence Assessment on the National Security Implications of Global Climate Change to 2030,” June 25, 2008. Available at http://www.dni.gov/testimonies/20080625_testimony.pdf. Accessed November 24, 2009. |

FIGURE 1.2 Climate measurements indicate that Arctic sea ice is shrinking and thinning. These Arctic maps show the median age of February sea ice, 1981–2009 (left) and February 2009 (right). As of February 2009, ice older than 2 years accounted for less than 10 percent of the ice cover. (Dark blue represents multiyear ice.) SOURCE: National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), University of Colorado, Boulder; data provided by James Maslanik and Charles Fowler, Colorado Center for Astrodynamics Research, Aerospace Engineering Sciences, University of Colorado.

for assistance if climate-related disasters increase.11 Recent events have shown that the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps will often be called upon as first responders on behalf of the United States to provide immediate and large-scale international HA/DR assistance and to help secure U.S. interests in sensitive regions.12 While

|

11 |

A 2007 joint maritime strategy document for the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard calls out “humanitarian assistance and disaster response” as one of six capabilities that constitute the core of U.S. maritime power and that “reflect an increased emphasis on those activities that prevent war and build partnerships.” See Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, available at http://www.navy.mil/maritime/MaritimeStrategy.pdf. Accessed November 23, 2009. However, it is not the sole responsibility of the U.S. military to respond to national and international humanitarian and disaster-relief emergencies; many U.S. and international governmental and private agencies may be engaged in any given relief operation. |

|

12 |

For example, in the aftermath of Tropical Storm Ketsana striking the Philippines on September 25, 2009, the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps worked with the Philippine government (and in support of the U.S. Department of State and the U.S. Agency for International Development Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance) to rapidly provide critically needed supplies in support of disaster relief to help mitigate human suffering and prevent further loss of life. In this case, a team of approximately 100 personnel composed of Marines from the III Marine Expeditionary Force flew from Okinawa to the Philippines on September 29, 2009, to conduct humanitarian assistance assessments. On September 30, the USS Denver, USS Tortuga, and USS Harpers Ferry, with embarked Marines and sailors of the 31st Expeditionary Unit, set sail from Okinawa toward the Philippines. On October 1, the com |

the above scenarios are likely, the pace and extent of this increase are unknown at this time.

Of all the theaters of naval operations that the committee considered could be impacted by climate change, the Arctic13 was found to have the most immediate challenges, all of which have relevance to each of the four areas identified in the terms of reference. For example, the reduction of Arctic sea ice has already led to increased activity in the Arctic Ocean. It is anticipated that major international maritime passages in the Arctic will be accessible by the year 2030, at least during the summer months. This change is due to the continued reductions in summer sea-ice cover in the Arctic Ocean and the rapid disappearance of older, thicker multiyear ice (see Box 1.2).14 A result of this will be greater summer marine access and longer navigation seasons in the Arctic Ocean, both having direct implications for the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard. The January 2009 National Security Presidential Directive (NSPD)-66/Homeland Security Presidential Directive (HSPD)-25 discusses relevant U.S. national security concerns in the Arctic, including such matters as missile defense and early warning, deployment of sea and air systems for strategic sealift, strategic deterrence, maritime security operations, and ensuring freedom of navigation.15 The U.S. Navy and Coast Guard must be positioned to meet maritime domain awareness (MDA) requirements and to recognize and respond to any potential security interests confronting the United States in this changing maritime domain.16

The United States Geological Survey (USGS) notes that significant natural resources (oil, natural gas, and nonfuel minerals) may become increasingly accessible for exploration and exploitation as Arctic sea ice melts on a seasonal basis. The 2008 USGS Circum-Arctic Resource Appraisal reports that the extensive Arctic continental shelves may constitute the geographically largest unexplored area for petroleum products remaining on Earth, with an estimated 90 billion bar-

|

manding general of the 3rd Marine Expeditionary Brigade flew from Okinawa to the Philippines to lead planning and humanitarian assistance efforts. See U.S. Marine Corps News. Available at http://www.okinawa.usmc.mil/public affairs/info/archive/news. Accessed November 23, 2009. |

|

13 |

In this report, the Arctic region is defined as the land and sea area north of the Arctic Circle, the circle of latitude at approximately 66.56 degrees north of the equator. The North Pole, the northernmost point of the axis around which Earth rotates, lies at the center of the Arctic region. |

|

14 |

Multiyear ice remains frozen throughout the year and is typically 2 to 5 m thick. First-year ice is formed in the winter but melts during the summer and is typically 0.3 to 2 m thick. Sea ice, as a general term, includes multiyear and first-year ice. |

|

15 |

The January 2009 National Security Presidential Directive (NSPD)-66, dual titled as Homeland Security Presidential Directive (HSPD)-25, or NSPD-66/HSPD-25, establishes the policy of the United States with respect to the Arctic region and outlines national security and homeland defense interests in the region. See National Security Presidential Directive-66, Article III B 1; available at http://www.fas.org/irp/offdocs/nspd/nspd-66.htm. Accessed July 28, 2010. |

|

16 |

U.S. naval officials define maritime domain awareness as “the effective understanding of anything associated with the maritime domain that could impact the security, safety, or economy of the United States.” See Naval Operations Concepts 2010, Implementing the Maritime Strategy; available at http://www.navy.mil/maritime/noc/NOC2010.pdf. Accessed June 4, 2010. |

|

BOX 1.2 A Sea-Ice Tutorial Several forms of floating ice may be encountered by vessels at sea. The most extensive ice is that which results from the freezing of the sea surface, namely sea ice; but mariners must also be concerned with “ice of land origin”—icebergs, ice islands, bergy bits and growlers. Both icebergs and sea ice can be dangerous to shipping and always have an effect on navigation. Young ice: Newly formed sea ice less than 30 centimeters thick is described as young ice or new ice. It forms extensively in the autumn as ocean surface temperatures fall below freezing and on leads that open in mid-winter due to shifts in the pack ice. Young or new ice is not a significant safety hazard for most Arctic vessels, although when placed under pressure by winds or currents, it can impede progress. First-year ice: First-year ice can easily attain a thickness of 1 meter but rarely grows beyond 2 meters by the end of the winter. First-year ice is relatively soft due to inclusions of brine cells and air pockets and will not generally hole an ice-strengthened ship operated with due caution. Under pressure from winds or currents, first-year ice can impede progress to the point where even powerful vessels can become beset for hours or even days. Old ice: If first-year ice survives the summer, it is then classified as old ice (subdivided into second-year and multiyear ice). Multiyear ice is typically 2 to 5 meters thick and is extremely hard. During the summer melt process, the brine cells and air pockets that characterize first-year ice drain out the bottom of the ice, leaving a clear, solid ice mass that is harder than concrete. Even ice-strengthened vessels are at risk of being holed by old ice. When under pressure, old ice can stop the most powerful icebreakers. Icebergs: These are large masses of floating ice originating from glaciers. They are very hard and can cause considerable damage to a ship in a collision. Ice islands are vast tabular icebergs originating from floating ice shelves. Smaller pieces of icebergs are called bergy bits and growlers and are especially dangerous to ships because they are extremely difficult to detect. SOURCE: Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment 2009 Report, Arctic Council, April 2009, p. 22. |

rels of oil, 1,669 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, and 44 billion barrels of natural gas liquids still to be found in the Arctic, of which approximately 84 percent is expected to occur in offshore areas.17 Although exploration conditions are projected to remain harsh and challenging in the Arctic, shrinking sea ice provides greater access to these potential resources.

In the committee’s view, the climate-change-related changes in the Arctic hold the potential for international competition, conflict, or cooperation. The current geopolitical forces at play in the Arctic, when combined with climate model projections of continued reduction in Arctic sea ice, provide compelling evidence that future requirements for U.S. naval operations in the Arctic will significantly increase over the next 30 years.

CLIMATE CHANGE, ARCTIC CLAIMS, AND UNCLOS

Related to the increased international activity and interest in the Arctic described above, the fact that the United States has signed but not yet ratified the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea18 will become even more problematic with time and as more states call for international recognition of their Arctic claims (see Box 1.3). For example, the five Arctic coastal states—Canada, Russia, Norway, Denmark (based on its territory Greenland), and the United States—are in the process of preparing Arctic territorial claims for submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf. Russia’s claims to the Lomonosov Ridge, if accepted, would grant Russia nearly one-half of the Arctic. By remaining outside of UNCLOS, the United States seriously compromises its ability to take part in negotiations regarding the claims of other nations.19 UNCLOS provides a legal framework for the settlement of such disputes.

The current nonparticipation of the United States in UNCLOS has serious negative implications for U.S. naval forces and their operations in the Arctic.20 In

|

17 |

See Kenneth J. Bird, Ronald R. Charpentier, Donald L. Gautier (CARA Project Chief), David W. Houseknecht, Timothy R. Klett, Janet K. Pitman, Thomas E. Moore, Christopher J. Schenk, Marilyn E. Tennyson, and Crain J. Wandrey, 2008, “Circum-Arctic Resource Appraisal: Estimates of Undiscovered Oil and Gas North of the Arctic Circle,” U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet, 2008-3049; available at http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/2008/3049/. Accessed June 4, 2010. |

|

18 |

An extensive discussion of the international legal framework for UNCLOS is provided in National Research Council, 2008, Maritime Security Partnerships, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C., Appendix C. |

|

19 |

An overview and full text of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea are available at http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_overview_convention.htm. Accessed November 23, 2009. |

|

20 |

U.S. Navy and Coast Guard leadership have provided public testimony on the potential value and impact of UNCLOS ratification on U.S. naval operations. For example, in a May 20, 2010, speech on the Arctic at the National Press Club, ADM Gary Roughead, Chief of Naval Operations, stated that the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea “is the vehicle by which we can collectively provide continuing stability in the maritime domain…. As the only permanent member of the UN Security |

|

BOX 1.3 Summary of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the Arctic UNCLOS provides an important international legal and political framework for the Arctic, with a broader aim to regulate all aspects of the resources of the sea and uses of the global ocean, including freedom of navigation. Its 320 articles and 9 annexes propose governing rules for all aspects of ocean space, including marine scientific research, commercial activities, the permissible breadth of the territorial sea (the part of the ocean nearest the shore, over which the coastal state enjoys sovereignty), maximum freedom of the seas, and the settlement of disputes relating to ocean matters. According to UNCLOS, coastal states have undisputed sovereign rights to their territorial sea and exclusive economic zone, which extend to a distance of 200 nautical miles from their coastal baseline. Upon ratification of UNCLOS, a country has 10 years to make claims to extend its 200-nautical-mile zone. As of January 2010, over 160 parties have ratified UNCLOS. Article 76 of UNCLOS provides the rules by which coastal states may establish those outer limits. The Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf is the governing body for these Arctic claims. In the case of the Arctic Ocean, the five Arctic coastal states are Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia, and the United States. Russia ratified UNCLOS in 1997. In December 2001, Russian officials submitted a claim that 120 million hectares of underwater terrain between the Lomonosov and Mendeleev ridges be confirmed as a continuation of the Siberian shelf. Norway ratified UNCLOS in 1996 and submitted its claim in November 2006. Canada and Norway ratified UNCLOS in 2003 and 2004, respectively, and are in the process of preparing claims for submission. The United States has not ratified UNCLOS. However, the United States is working closely with Canada to gather and analyze data through the Extended Continental Shelf Project for the submission of Canada’s claim. This effort is led by the U.S. Continental Shelf Task Force, an interagency body, chaired by the Department of State with co-vice chairs from NOAA and the Department of the Interior. Both U.S. Navy and U.S. Coast Guard representatives participate on the Task Force. According to the U.S. Arctic Research Commission, the United States could lay claim to an area in the Arctic of about 450,000 square kilometers and the seabed resources therein. However, as a non-party to UNCLOS, the United States cannot participate as a member of the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf; neither can the United States submit a claim under Article 76. SOURCE: See United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, available at http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/convention_overview_convention.htm. See also http://continentalshelf.gov/. |

this regard, the committee’s perspectives on UNCLOS are in line with those of Department of Defense leadership, including the Secretary of Defense, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Secretary of the Navy, the Chief of Naval Operations, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, and the Commandant of the Coast Guard regarding ratification of UNCLOS.21

Freedom of the seas issues addressed in UNCLOS are also important for U.S. naval forces, beyond an increasingly accessible Arctic due to melting sea ice. U.S. naval forces depend upon global strategic mobility and tactical maneuverability to conduct the spectrum of sea-air-land operations in the pursuit of national interests. Similar to NSPD-66, the 2005 United States National Strategy for Maritime Security identified freedom of the seas as a top national priority.22 Also, the Department of Defense and the Joint Chiefs of Staff discussed the major national security benefits of the Law of the Sea Convention in a 1996 report. The foremost benefit seen by this group was reported as global access to the oceans throughout the world—specifically, freedom of navigation, overflight, and telecommunications—and a stable and nearly universally accepted convention to promote public order and free access to the oceans and the airspace above them.23

The committee has studied the implications of the failure of the United States to ratify the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea from the standpoint of potential impacts on national security due to climate change. As climate change affords increased access to the vast Arctic, the committee envisions new opportunities for natural resource exploration and recovery as well as increasing shipping traffic of all kinds; with that will be a corresponding need for broadened naval

|

Council outside the convention, the only Arctic nation that is not part [of the convention], and one of the few nations still remaining outside one of the most widely subscribed international agreements in world history, we hinder our ability to lead…. We cannot stand outside the Convention and watch as other nations inside the convention accept the legal framework on issues of navigation, sovereignty, and resource rights that are critical to our nation. Having a seat at the table is extraordinarily important and it will diminish our maritime interests in the future if we do not subscribe to this.” Communication to the committee from CAPT Timothy Gallaudet, USN, Deputy Director, Navy Task Force Climate Change, June 4, 2010. |

|

21 |

For example, the 2010 DOD Quadrennial Defense Review provides endorsement for U.S. ratification of UNCLOS in its discussion of climate and energy (see Quadrennial Defense Review, February 2010, p. 86 [page 108 of the PDF file], available at http://www.nationaljournal.com/congressdaily/issues/graphics/Defense-Review-2010.pdf). The committee realizes that the U.S. ratification of UNCLOS involves a number of nonmilitary issues. For additional reading, see Ronald O’Rourke, 2010, Changes in the Arctic: Background and Issues for Congress, Congressional Research Service, Washington, D.C., March 30, pp. 6-7; and National Intelligence Council, 1996, Law of the Sea: The End Game, Intelligence Community Assessment, March. Available at http://www.dni.gov/nic/special_endgame.html. Accessed November 23, 2009. |

|

22 |

White House (George W. Bush). 2005. The National Strategy for Maritime Security, Washington, D.C., September. |

|

23 |

See U.S. Department of Defense, National Security and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, Second Edition, 1996; available at http://www.dod.gov/pubs/foi/reading_room/876.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2010. |

partnership and cooperation, and a framework for settling potential disputes and conflicts. By remaining outside the Convention, the United States makes it more difficult for U.S. naval forces to exercise maximum operating flexibility in the Arctic. Nonparticipation also complicates negotiations with partners for coordinated search and rescue operations in the region.

Beyond the Arctic, the committee anticipates increased HA/DR missions by U.S. naval forces as a result of projected increases in extreme climatic events. To support this potential increasing mission for humanitarian assistance to climate refugees and disaster-relief operations, allied partnerships will be essential. Hence the committee sees ratification of the Convention as an important national priority to leverage the enormous “soft power” of the treaty to share burdens and reduce the national security risks to the naval and joint forces and the nation. Becoming a party to the Convention then is clearly in the U.S. naval forces’ best interests as the Arctic opens as a fifth ocean of interest.

FINDING 1.1: The committee has studied the implications of the failure of the United States to ratify the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) from the standpoint of potential impacts on national security in the context of a changing climate. As climate change affords increased access to the Arctic, it is envisioned that there will be new opportunities for natural resource exploration and recovery, as well as increased ship traffic of all kinds, and with that a need for broadened naval partnership and cooperation, and a framework for settling potential disputes and conflicts. By remaining outside the Convention, the United States makes it more difficult for U.S. naval forces to have maximum operating flexibility in the Arctic and complicates negotiations with maritime partners for coordinated search and rescue operations in the region.

RECOMMENDATION 1.1: The ability of U.S. naval forces to carry out their missions would be assisted if the United States were to ratify UNCLOS. Therefore, the committee recommends that the Chief of Naval Operations, the Commandant of the Marine Corps, and the Commandant of the Coast Guard continue to put forward the naval forces’ view of the potential value and operational impact of UNCLOS ratification on U.S. naval operations, especially in the Arctic region.

NAVAL FORCES’ POSITIONING ON CLIMATE CHANGE AND ENERGY

The leaders of the U.S. Navy, Coast Guard, and Marine Corps have recognized the potential impact of climate change on naval forces and have positioned their organizations to make adaptive changes.24 For example, a joint Navy, Marine,

and Coast Guard maritime strategy document identifies climate change as an area of concern and discusses areas for future potential naval attention.25 In this regard, the CNO has recognized the linkage between energy use and climate change by establishing two key task forces: Navy Task Force Energy (charged with formulating a strategy and plans for reducing the Navy’s reliance on fossil fuels—and thus reducing carbon dioxide emissions, operational energy demands, and, potentially, energy costs);26 and Navy Task Force Climate Change (charged initially with developing a road map for Navy actions in the Arctic, and then with addressing longer-term Navy actions regarding global climate change policy, strategy, and plans).27 This committee engaged with Navy Task Force Energy and Navy Task Force Climate Change and found that each is providing strong leadership on these issues across the Navy and DOD. Both task forces are well positioned in capability and credibility to continue their strong contributions.

Navy Task Force Climate Change issued its first report, U.S. Navy Arctic Roadmap, on November 10, 2009. The Arctic Roadmap is the first phase of a planned multistep approach for the U.S. Navy to address major climate change issues. The road map offers a chronological listing of Navy action items, objectives, and desired effects to address climate-change-related Arctic issues for the period FY 2010-FY 2014. Included in this Arctic road map are the following recommended FY 2011-2014 actions, actions that the Navy is reported to be acting upon or taking under consideration:28

-

Initiate assessments of required Navy Arctic capabilities

-

Develop recommendations to address Arctic requirements for program proposals in the Navy’s Program Objective Memorandum for FY 2014 (POM-14)

-

Continue biennial Navy participation in Arctic exercises, including ICEX-11, ICEX-13, Arctic Edge, and Arctic Care

-

Formalize new cooperative relationships that increase Navy experience and competency in search and rescue (SAR), maritime domain awareness (MDA), and humanitarian assistance and disaster response in the Arctic, and defense support of civil authorities (DSCA) in Alaska.29

|

25 |

See A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, Washington, D.C., 2007, p. 3. Available at http://www.navy.mil/maritime/MaritimeStrategy.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2010. |

|

26 |

CAPT James L. Brown, USN, Director, Navy Energy Coordination Office, Office of the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Fleet Readiness and Logistics, “Navy Task Force Energy, Perspectives and Related Climate Change Initiatives,” presentation to the committee, September 17, 2009, Washington, D.C. |

|

27 |

See Vice Chief of Naval Operations (ADM W. Jonathan Greenert, USN), Memorandum 4000 Ser N09/9U103035, “Task Force Climate Change Charter,” October 30, 2009. |

|

28 |

CAPT Timothy Gallaudet, USN, Deputy Director, Task Force Climate Change/Oceanographer of the Navy, “Task Force Climate Change Update and Gaps and Projected Future Needs,” presentation to the committee, October 19, 2009, Washington, D.C. |

|

29 |

CAPT Timothy Gallaudet, USN, Deputy Director, Task Force Climate Change/Oceanographer of the Navy, “Task Force Climate Change Update and Gaps and Projected Future Needs,” presentation to the committee, October 19, 2009, Washington, D.C. |

As is evident in this report, the committee fully agrees with these initial actions and recommendations of TFCC. In developing future plans for Navy actions in and beyond the Arctic, TFCC has reported that it will draw upon the findings and recommendations from this report and other commissioned assessments.30 Related, the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) has commissioned the U.S. Coast Guard High Latitude Region Mission Analysis study to better define its specific requirements for protecting U.S. national security interests in the Arctic. The USCG study is anticipated to be completed in the third quarter of 2010.31

ADDITIONAL RELEVANT CLIMATE CHANGE ASSESSMENTS

Additional assessments on climate change and its impacts include the U.S. Global Change Research Program’s 2009 report on Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States. Key findings of this government document were as follows:32

-

Global warming is unequivocal and is primarily human induced.

-

Climate changes are under way in the United States and are projected to grow.

-

Widespread climate-related impacts are occurring now and are expected to increase.

-

Climate change will stress water resources.

-

Crop and livestock production will be increasingly challenged.

-

Coastal areas are at increasing risk from sea-level rise and storm surge.

-

Threats to human health will increase.

-

Climate change will exacerbate many social and environmental stresses.

-

Thresholds will be crossed, leading to large changes in climate and ecosystems.

-

Future climate change and its impacts depend on choices made today.

Additionally, in response to a request from Congress, the National Research Council initiated the study America’s Climate Choices, designed to inform and guide responses to climate change across the nation. Experts representing various levels of government, the private sector, nongovernmental organizations, and research and academic institutions populated panels on the following:

|

30 |

The reader should note that Navy Task Force Climate Change was chartered to focus on issues for the U.S. Navy, whereas the terms of reference for this committee focus on issues impacting the U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard. |

|

31 |

ADM Thad Allen, Commandant, U.S. Coast Guard, briefing to the committee, November 20, 2009, Washington, D.C. |

|

32 |

U.S. Global Change Research Program. 2009. Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States, Cambridge University Press, New York. |

-

Advancing the Science of Climate Change,

-

Adapting to the Impacts of Climate Change,

-

Limiting the Magnitude of Future Climate Change, and

-

Informing Effective Decisions and Actions Related to Climate Change.

Reports from each of the first four America’s Climate Choices panels are now available and should help inform future U.S. naval leadership decisions. For example, the Advancing the Science of Climate Change report recommends that a single federal entity or program be given the authority and resources to coordinate a national research effort integrated across many disciplines and aimed at improving both understanding and responses to climate change. The U.S. Global Change Research Program, established in 1990, could fulfill this role, but it would need to form partnerships with action-oriented programs and to address weaknesses in its current program. A comprehensive climate observing system, improved climate models and other analytical tools, investment in human capital, and better linkages between research and decision making are also essential to a complete understanding of climate change.33 As discussed in Chapter 6 of this committee’s report, the Navy is in position to both contribute to and benefit from such an effort.

PROPOSED NATIONAL AND GLOBAL FRAMEWORKS FOR CLIMATE SERVICES

In addition to needs expressed by the DOD and military services for better (decadal or longer) climate model projections, individuals and decision makers across widely diverse sectors—from agriculture to energy to transportation—increasingly are asking for information about climate change in order to make the best choices for their families, communities, and businesses. This translates to the provision of climate information on the regional level that investors, business leaders, natural resources managers, and policy makers need to help prepare for the adverse impacts of potential climate change on industries, communities, ecosystems, and nations. While global mean metrics of temperature, precipitation, and sea-level rise are convenient for tracking global climate change, many sectors of society require actionable information on considerably finer spatial and temporal scales—such as seasonal predictions with regard to Arctic sea ice and the seasonal prediction of hurricanes and other severe storms in specific areas of the world.

To meet the rising demand of these requests, the U.S. Commerce Secretary announced in February 2010 the intent to create a NOAA [National Oceanic and

|

33 |

The initial four reports from the America’s Climate Choices (ACC) studies are these: National Research Council, 2010, Advancing the Science of Climate Change, Informing an Effective Response to Climate Change, Limiting the Magnitude of Future Climate Change, and Adapting to the Impacts of Climate Change, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. Additional information on the ACC studies is available at http://americasclimatechoices.org. Accessed June 4, 2010. |

Atmospheric Administration] Climate Service line office dedicated to bringing together the agency’s strong climate science and service delivery capabilities.34 One of the challenges to be faced by an effective Climate Service is the sheer interdisciplinary breadth of providing climate services across such sectors as agriculture, parks and recreation, terrestrial ecosystems, insurance and investment, energy, state/local/municipal governments, water, human health, commerce and manufacturing, transportation, and coastal and marine sectors.

The impact of climate on many of these sectors has direct implications for national security. Internationally, a question of paramount importance confronting nations is how to adapt to the prospect of climate variability and change in the next half century. In response, the World Climate Conference-3 convened in Geneva, Switzerland, in 2009 to establish a Global Framework for Climate Services that addresses the needs of decision makers worldwide for accurate and timely climate information and predictions. Delegations from 163 nations met in Geneva to ensure that current and future generations have access to the climate predictions and information necessary for various socioeconomic sectors to cope with climate variability and change.35

RISK MANAGEMENT IN THE FACE OF FUTURE CLIMATE CHANGE PROJECTIONS

This committee believes that there is strong scientific evidence to recommend that U.S. naval leadership should continue their ongoing attention to the national security implications of climate change, specifically its potential impact on future naval operations and capabilities. However, current scientific understanding and predictive capability for climate change lack the specificity that the Navy needs for planning purposes. Deficits in knowledge include, for example, the rate of future sea-level rise, the timing for the opening of Arctic waters, and reliable predictions of regional climate (given the current inability to project specific regional impacts). Considering that it is unlikely that the precision of climate change projections will dramatically improve in the next few years, the committee believes that the Navy should adopt a risk management approach for addressing these issues. Such an approach should include a range of contingency plans for the potential onset of climate-driven severe-weather disasters.

|

34 |

See Commerce Department Proposes Establishment of NOAA Climate Service, NOAA news release, February 8, 2010; available at http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2010/20100208_climate.html. Accessed June 4, 2010. |

|

35 |

Participants at the World Climate Conference-3 approved, by acclamation, a conference declaration deciding to establish a Global Framework for Climate Services (GFCS) to strengthen production, availability, delivery, and application of science-based climate prediction services, and they outlined a path forward for establishing the GFCS. “Summary of the World Climate Conference,” World Climate Conference Bulletin, Vol. 165, No. 1, September 2009. Available at http://www.iisd.ca/ymb/climate/wcc3/html/ymbvol165num1e.html. Accessed June 4, 2010. |

Some recent reports have also noted the possibility of “climate surprises,” that is, unexpected rapid changes outside of current climate model projections.36 Such surprises would likely be associated with fast processes and interactions/feedbacks among different Earth system components, including physical, chemical, and biological aspects. Naval operations could be particularly affected by these “surprises” if there is abrupt acceleration of sea-level rise, rapid sea-ice loss, rapid thawing of the permafrost releasing additional CO2 or methane into the environment, or an increase in strong tropical cyclones. However, means for reliably predicting such abrupt changes are not currently available.

The committee discussed, but did not explore in depth, risk management for climate change planning. The committee is aware, however, of a growing body of knowledge in this area. These risk analysis approaches examine means for conceptualizing and managing risk for “fat-tailed distribution” events, which may exhibit abrupt change or have high impact and are not mathematically well behaved.37 While the insurance industry is the target and sponsor for many of these examinations, the principles and issues explored are applicable to naval climate change risk analyses.38

Many uncertainties remain about the course of climate change, and these will probably continue in the near term. It is noteworthy that the U.S. Navy’s assets and entities, including the Office of Naval Research, the Naval Research Laboratory, and the Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command, are recognized by climate scientists as critical partners in advancing the understanding of climate science and related policy implications.39 The committee strongly supports the continuation of dedicated efforts by the Navy to remain engaged with and assist

|

36 |

Thomas R. Karl, Gerald A. Meehl, Susan J. Hassol, Anne M. Waple, and William L. Murray (Eds.). 2008. Weather and Climate Extremes in a Changing Climate, Department of Commerce, NOAA’s National Climatic Data Center, Washington, D.C. |

|

37 |

In statistics, the term “fat-tail distribution” is used to describe the probability of high-consequence events that fall on the tail end of a statistical distribution and cannot be accurately described by the normal distribution bell-shaped curve. In these cases, the probability of an extreme event, though unlikely, is higher than it would have been under the normal hypothesis and assignment of risk. |

|

38 |

For example, see Carolyn Kousky and Roger M. Cooke, 2009, “Climate Change and Risk Management: Challenges for Insurance, Adaptation and Loss Estimation,” discussion paper, Resources for the Future, Washington, D.C., February. Available at http://www.rff.org/documents/RFF-DP-09-03.pdf. Accessed July 28, 2010. |

|

39 |

U.S. Navy and Coast Guard assets have been highly important in providing critical scientific data associated with both ice mass and ocean changes over extended periods. Also, the Measurements of Earth Data for Environmental Analysis (MEDEA) Program, a project of the 1990s, has been highly valuable in providing sea-ice data from military and intelligence assets that would otherwise be unavailable in the civilian sector. See National Research Council, 2009, Scientific Value of Arctic Sea Ice Data, The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. In another example, Scientific Ice Expeditions (SCICEX) was a 5-year program in which the Navy made available a Sturgeon-class nuclear-powered attack submarine for unclassified science expeditions to the Arctic Ocean to gather ice-thickness measurements. Additional information on SCICEX is available at http://www.nsidc.org/noaa/scicex/. Accessed May 10, 2010. |

in leading advancements in climate science and understanding its impacts within the broader context of the DOD’s responsibility to assess the effects of climate change on all DOD missions, capabilities, and facilities. The Navy brings significant historical experience and unique assets to this arena, such as its specialized oceanographic fleet and its submarine under-ice data collection capabilities. The committee views these naval assets and related advances in fundamental knowledge as supportive of the national security interests of the United States. These advances will also aid in reducing the uncertainties in future climate change and response projections and the necessary national response.

FINDING 1.2: Many climate change issues with potentially high impact for U.S. naval forces are known through direct scientific evidence. However, many climate change uncertainties remain.

RECOMMENDATION 1.2: Naval leadership should continue leading the understanding of the impact of climate change for the DOD and contribute to better technical understanding. Naval leadership should adopt a risk analysis approach for dealing with the climate change uncertainties by developing response scenarios for accepted projections and for excursions away from the projections.

Throughout this report, the committee recommends actions that would address these more extreme excursions as a hedge against the possible and to help address a risk management approach.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

This report is organized to address the key naval issues requested in the study’s terms of reference and presents findings and recommendations in the six areas for naval leadership action outlined in the report Summary. Following the Chapter 1 introductory comments, Chapter 2 addresses national security and climate-change-related operational issues for U.S. naval forces.40 Where appropriate, Arctic operational issues for naval forces are articulated separately from global climate-change-related naval operational issues. Chapter 3 addresses physical infrastructure issues for U.S. naval forces, due primarily to projected climate-induced sea-level rise and storm surge and their potential impact on naval coastal installations around the globe. Allied forces issues are discussed and explored in Chapter 4, not only providing findings and recommendations for climate change issues associated with traditional U.S. allies but also addressing the need for broader naval military and international partnerships in planning for projected climate-induced HA/DR events. Chapter 5 discusses climate-change-

related technical issues for U.S. naval forces, including addressing antisubmarine warfare in a changing world ocean. Where appropriate, Chapter 5 also explores Arctic technical challenges separately from global climate-change-related technical challenges. Chapter 6, the concluding chapter of the report, provides an examination of future research and development needs and associated findings and recommendations for U.S. naval forces—concentrating on those areas in which the committee believes the naval forces have particular interests that might not likely be met in the near term by other groups pursuing climate science research.