10

What Are Sleep Disorders and How Should They Be Treated?

Sometimes, even after they’ve adjusted their sleep-wake patterns and have put much better sleep habits into practice—and even when they’re finally getting eight to nine hours of sleep time—teens can still feel tired and irritable during the day. Their health and performance may also continue to suffer, leaving parents at a loss as to what the problem is and what to do next.

Just like adults, teens can suffer from a sleep disorder other than Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome (DSPS) that can have very serious consequences. It’s estimated that more than 70 million Americans endure one of the many known sleep disorders and that many of these people develop the problem in their teens.

But diagnosis and treatment are often slow in coming. A 1998 study of 548 patients with narcolepsy, the first major national study that provided extensive information about the history of symptoms, revealed that it took patients an average of 15 years from the first complaint of sleepiness to a health care professional until a diagnosis was reached and treatment begun.

The reasons for this? There are several:

-

Detailed knowledge of sleep disorders is lacking in the general medical community. For the past 18 years I’ve been given only one

-

hour of time (this year it’s up to an hour and a half) in George Washington University’s medical school curriculum to teach medical students about sleep—that’s it for their entire four years of medical school. Older docs may not have received any formal training on sleep, since sleep as a specialty wasn’t even on the map until the mid-1980s.

-

People who are sleepy are often thought of as lazy. That makes it less likely that they’ll complain to their doctor about sleepiness and less likely that their complaint will be taken seriously.

-

The importance of sleep for general health and wellness is just moving into the forefront of medical and societal thinking.

-

The soaring costs of health care have limited the time that doctors spend one on one with their patients as well as increased the probability that patients will change doctors as their health plans change. That makes it less likely that a doctor will get to know a patient well enough to make a more challenging diagnosis.

-

Symptoms of sleep disorders can mimic those of sleep deprivation. Patients may not pursue a diagnosis when they’re told that the answer to their problem is to get more sleep.

Diagnosing a teen’s sleep disorder can be even more challenging because society believes that sleepiness and sleep-ins are the norm for adolescents. But if your teen’s delayed-phase issues have been addressed and she still has trouble falling asleep and is excessively sleepy all day, it’s time to look into the possibility of a coexisting or alternative sleep disorder.

Because sleep disorders can be the result of, or be associated with, a number of medical conditions, the best way to begin your sleuthing is to have your teen undergo a general physical checkup. If nothing relevant is found, seeing a therapist or psychiatrist for depression-related or behavior-related symptoms may be called for. An overnight sleep study in a sleep lab may provide critical information about how and when your teen sleeps, and a daytime nap study will show the severity of sleepiness.

While there are many different sleep disorders—85 are recognized by the American Sleep Disorders Association—I’m going to cover the four I see most commonly in teens: sleep apnea, narcolepsy, restless

legs syndrome, and insomnia. I’ll describe typical symptoms and effects to look for and the best available treatments.

Sleep Apnea

While we don’t know exactly how many teens experience sleep apnea, it’s estimated that 18 million Americans suffer from its effects. The disorder is characterized by loud disruptive snoring, pauses in breathing, gasping for breath, and excessive daytime sleepiness. It can result in headaches, irritability and/or depression, concentration and memory problems, and frequent nighttime urination as well as the very serious consequences of increased risk of high blood pressure, stroke, heart attack, and, in severe cases, death. In adults it can also have the unhappy result of the bed partner needing to sleep in another room—the loud snoring can cause bunkmates to flee before they develop sleep problems of their own.

|

IT’S A FACT The word “apnea” comes from the Greek word “pnea,” which means to breathe or breathing. In its English version, with the prefix “a,” the word means without or not breathing. |

What causes all of this mayhem? When a person suffers from sleep apnea, the airway closes completely during sleep, keeping the necessary amount of oxygen from reaching the lungs, body, and brain. To understand how this happens, let’s first take a look at what goes on when we breathe.

We breathe as a result of the activity of pacemaker cells located deep in the brain stem. When it’s time for us to breathe in, these cells send signals to the chest wall to expand and to the diaphragm to flatten. These actions cause negative pressure to form within the chest cavity, which results in air being sucked in. When it’s time to breathe out, the cells tell the muscles of the chest wall and diaphragm to relax, which results in the air being pushed back out. I like to think of people as living accordions, automatically taking air in and sending it out.

Sometimes, though, we choose to override that autopilot system and take an extra deep breath or hold a breath—to blow up a balloon, to dive into a lake, to torture our parents by seeing if we can hold our breath longer than our sibling, for any number of good or nonsensical reasons. We do have some voluntary control over our respiratory muscles and can clamp down on our chest wall muscles to prevent the breath that our pacemaker cells want us to take.

That’s fine for 10 or 15 seconds of a breath hold. Initially the pacemaker cells don’t get agitated and neither do you—you have a great time trying to outdo your brother or sister. But if you try to hold your breath much longer, the respiratory centers do get more agitated— they get the message that you didn’t take a breath and so start sending urgent signals for you to breathe. You can fight them a little longer if you want, but in the end they win—the brain’s respiratory centers, which are extremely powerful, force you to take a breath. (Darn, your sibling gets one up on you.)

Though this is the process that happens in the daytime, it’s important for understanding what happens with breathing—and sleep apnea—at night. When you lie down to sleep at night, whether or not you have sleep apnea, your brain stem respiratory centers are set to provide you with nice, deep breaths all night long. The muscles in your airway may relax a bit, the way all your muscles relax when you make the transition to sleep, but basically you’re set up to breathe well and easily and keep your brain and body oxygenated.

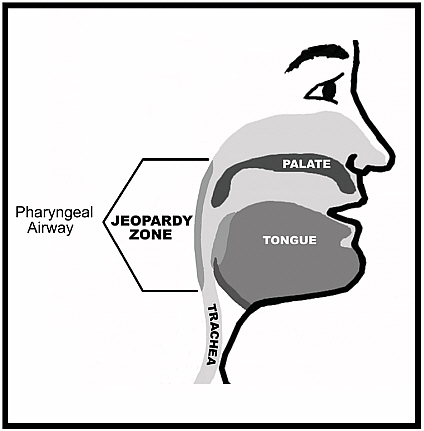

For people with sleep apnea, though, breathing during sleep does not go well. For reasons scientists don’t yet understand, sleep apnea sufferers have excessive relaxation of the muscles of the airway around the level of the pharynx—the part of the airway behind the mouth and the tongue—turning what is usually a smooth-walled tube into an irregularly walled, crinkly, smaller, more lax opening. This condition causes sleep apnea patients’ airflow to go from fast, efficient, direct, and quiet to loud and turbulent—air gets caught in the pockets of the airway, causing vibrations in the wall of the pharynx—which we know as snoring.

The pharyngeal segment of the airway is lined with muscles that form an open “tube” when the muscles have a good level of tone (resistance) during wakefulness. It is this region of the airway that may relax and close during sleep in individuals with sleep apnea.

|

IT’S A FACT Structures in the airway can also contribute to snoring. For example, if you have a long, wide uvula—the small, fleshy appendage that hangs down from the back of your throat—it can lose muscle resistance at night and vibrate in the breeze of breathing. If your tonsils are large, as they can be in kids, they can add to airway irregularity and contribute to snoring as well. |

If this is happening to you, things now get really dicey. You’re snoring, which is making your bed partner crazy. But beyond that, when you are soundly asleep (in Stage 2), your respiratory centers now signal your chest and diaphragm muscles to take in a bigger pull of

In an individual with sleep apnea there is normal airflow while awake (top). With the onset of drowsiness there is relaxation of the pharyngeal airway resulting in turbulent airflow and snoring (middle). Once asleep, further airway relaxation together with deeper breaths may result in episodic airway closure–sleep apnea (bottom).

air—nice, deep sleep breaths. But as the snoring indicates, your airway is partially closed. So when you draw in air, a vortex develops—a whirling, sucking force that pulls in everything around it—and you suck your own airway shut.

But the respiratory centers don’t know this—they think you’re breathing because your chest and diaphragm are still moving, trying to

pull in air, and they’re sending feedback to the brain that they’re doing a good job. They don’t realize that no air is moving into the lungs. So they signal your muscles to take another deep breath, which causes you to try to pull air through the closed airway—and reinforces the closure. With your airway closed, you get stuck in a blind loop in which you take in no air—an apnea.

|

A MORE SUBTLE FORM OF SLEEP APNEA While some teens and children do have flagrant sleep apnea, many others have a more subtle pattern of slight airway closure that results in increased resistance to airflow and an increased rate of arousal. This pattern, called Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome, is considered pathological and can be associated with daytime tiredness. It is more challenging for physicians to make a diagnosis of this condition; a high index of suspicion is necessary. |

Luckily, though, your body comes to the rescue. Though your respiratory centers don’t recognize that you’re not moving air, sensory regions in the major blood vessels that supply blood to the brain—the carotid arteries—realize that the blood passing through them is not fully oxygenated and that carbon dioxide levels may be rising, which means the brain and the body aren’t getting the energy they need. Then the carotid arteries activate a reflex mechanism that causes you to partially awaken, though awakenings that accompany apnea events generally are too short to be seen. The awakening, though, increases muscle resistance in the pharyngeal airway and signals the respiratory centers to call for stronger air pulls from the chest wall muscles. This helps to break open the airway and causes you to make a big snorting noise. Airflow is restored—until you drift back to sleep and the whole process starts all over again.

How long does this destructive cycle last? Apnea events typically last 20 seconds but can last longer than a minute—much longer than most people can hold their breath—and they can occur repeatedly all night. Fewer than three events per hour is considered normal in teens and under five per hour in adults, but people with severe sleep apnea

have been known to have 60 or even 80 events an hour. That means that not only is their sleep constantly interrupted, making them exhausted and functionally impaired during the day, but also that their health is at greatly increased risk. Waking up to some extent with each apnea event keeps those with the disorder from cycling through all the stages of sleep in sequence and for the proper length of time. Instead, they drift into Stage 1, move into Stage 2, gasp awake to breathe, drift back into Stage 1, move into Stage 2, gasp awake to breathe, over and over again.

Who is most at risk for sleep apnea? While the typical age of onset is 50, and more men are affected than women, teens, especially those with small chin and jaw structures and those who are overweight, also can develop the disorder. Other conditions that put people at risk include:

-

A short neck

-

A large neck circumference, often 17 inches or greater

-

Smoking

-

High blood pressure

-

Obesity

-

A close relative with sleep apnea

-

Enlarged tonsils

-

Allergies

-

Sinus problems

-

Asthma

Children with Down syndrome also have increased risk because of small chins, enlarged tonsils, and reduced muscle resistance (hypotonia).

The signs of sleep apnea, as I said earlier, can include significant daytime sleepiness when getting plenty of sleep at night. Snoring is often a key as well, but kids can have sleep apnea without doing a lot of snoring (female adults can also snore less and more quietly). Restless sleep can be an indicator of sleep apnea—the bed covers may be greatly disturbed in the morning—as well as coughing, labored breathing while asleep, acid reflux or heartburn, and many brief awakenings.

During the day, teens with sleep apnea may have little energy and a low mood, but, unlike adults, they may also show their exhaustion in giddiness, hyperactivity, and distractibility. Sometimes teens with sleep apnea are thought to have attention deficit disorder (ADD), because the tiredness is manifested in difficulty with focus, concentration, and attention— key symptoms of ADD, a more common problem in this age group (see Chapter 11).

SNOOZE NEWS

In a recent study of professional football players, 30 percent met the criteria for a diagnosis of sleep apnea. Having a body type that includes a short neck and an increased neck circumference can protect players from neck injuries when they butt heads on the field, but it puts them at risk for obstructive sleep apnea.

Because sleep apnea—and other sleep disorders—may share symptoms of ADD and other more common disorders, it’s important for parents to bring concerns about sleep apnea to the attention of their son or daughter’s doctor. Many of today’s physicians aren’t tuned into the possibility of this diagnosis, because tiredness can be associated with the symptoms of several other medical, emotional, and behavioral problems. If you suspect your teen has sleep apnea or another sleep disorder, you may need to become an advocate to make sure she receives help. A sleep study and daytime nap study may be the ultimate diagnostic tools.

A Case History

Chris, a 16-year-old boy, came to see me because he was sleepy all the time and his parents were concerned that he had sleep apnea; Chris’s dad had sleep apnea, and they wondered if it could run in families. When I took Chris’s history and examined him, I discovered that he had large tonsils but a normal chin position and neck circumference. He wasn’t overweight; in fact, he was more on the thin side. His mother told me that he snored a lot, and Chris told me that he played basketball, went to a tough school, had a major academic load, and that he always felt exhausted. He was getting six to seven hours of sleep a night, usually from about midnight to 6:00 or 6:30, and a little more on weekends.

Because of the snoring and the fact that Chris’s dad had sleep ap-

nea, my antenna went up and I recommended Chris undergo an overnight sleep study. In addition, I asked him to do a daytime nap study to see exactly how sleepy he was; from his information I knew he was severely sleep deprived. For two weeks before the studies, though, I had Chris regulate his sleep-wake schedule, allocating eight hours for sleep and maintaining a regular pattern. Regulating his schedule in this way would allow us to get an accurate read of his baseline degree of sleepiness.

When Chris did the nap study, it showed that he was profoundly sleepy—he fell asleep in less than five minutes at every nap opportunity we gave him throughout the day. (Well-rested people don’t normally sleep at all during nap opportunities.) But the overnight study had even more striking results. It showed that Chris had severe sleep apnea, with 42 apnea events during each hour of sleep—a very surprising finding in a young man without many common risk factors.

Treatment came in three parts. First, I urged Chris to continue to allocate a minimum of eight hours for sleep so that sleep deprivation would not confound his symptoms. Second, because his tonsils were very large, nearly obstructing his airway, I recommended an evaluation by an ear, nose, and throat surgeon. Third, I highly recommended he use a CPAP device (see below) to prevent his airway from closing so that he could have uninterrupted airflow and quality sleep. After protesting quite a bit, because of the way the device would make him look, he decided to use it, and at his first checkup the combination of a longer sleep time and normalized sleep airflow made for a huge improvement. Chris was well rested and felt great. His parents’ suspicions had resulted in needed treatment and relief from his symptoms.

If a diagnosis of sleep apnea is made, there are several forms of treatment available. For teens with large tonsils like Chris, a trip to an ear, nose, and throat doctor may result in a tonsillectomy, which can do a great deal to open up the airway. Kids with allergies can use a topical nasal spray or decongestant to ease blocked passages and improve airflow. Overweight teens can help manage their apnea by going on a weight loss and exercise program and keeping the weight off permanently. A dental appliance, in which the top and bottom plates are hinged together, also helps by moving the lower jaw and tongue for-

CPAP treatment may be delivered by a small mask covering the nose or a nasal pillow system that seals against the nostrils and connects via tubing to a small air compressor unit at the bedside. The pressure of the inspired air acts like a splint and holds the airway open, which normalizes airflow.

ward to make more space for the airway. If teens have a very small or receding chin or a chin or jaw malformation, surgery to realign the jaw, though a major undertaking with risks, can bring substantial relief. For teens with Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome, any of the above recommendations may help as well as a noninvasive procedure, such as a laser-assisted uvolopalatectomy or injection snoreplasty, to trim the uvula and soft palette.

The most effective, and least risky treatment, however, is for patients to use a CPAP, or Continuous Positive Airway Pressure, device while they sleep. The device, which consists of a mask that fits over the nose or plugs that fit into the nostrils and an air compressor attached

to the mask with a hose, pressurizes the air that users breathe in. The increased pressure acts like a splint and holds the airways open, preventing collapse.

Though it’s cumbersome to be hooked up to and takes some getting used to, the CPAP device is more than 95 percent effective in preventing apnea events. If adolescents feel weird wearing the mask— or if adults feel self-conscious in front of their bed partner—I always remind them that no one cares what you look like when you sleep, especially if you can be pleasant, energetic, and upbeat the next day.

That said, however, no adolescent on the planet wants to sleep with a CPAP device. So we usually make every effort to use alternate means to treat sleep apnea in teens. However, some teens, like Chris, have such a severe case and such severe symptoms that CPAP is warranted. It helped him enormously, as did having his enlarged tonsils removed several months after I saw him. In fact, the improvements in both the sleep apnea and the daytime sleepiness were so dramatic that Chris was able to stop using the CPAP device.

Narcolepsy

Narcolepsy is a chronic sleep disorder that affects 1 in 2,000 people. The disorder impairs the brain’s ability to maintain a normal, sustained awake period—patients have overall sleepiness and may experience sudden sleep attacks at times when they should be awake. They also may experience cataplexy, a condition brought on by strong emotion in which muscle resistance is either abruptly weakened or extinguished and the person wobbles or falls to the floor. Other symptoms can include vivid dreams, or hypnogogic hallucinations, while making the transition into or out of sleep, and the normal paralysis of REM sleep persisting into wakefulness—a frightening condition in which you’re awake but can’t move. People who have narcolepsy generally sleep an appropriate number of hours at night but still feel sleepy during the day.

While the reason behind the disorder isn’t fully understood, a genetic theory and an immunological theory have both been proposed. Recent studies indicate that the disorder is associated with a lack of hypocretin, a brain neurotransmitter that’s found in the sleep-

|

One Patient Says … “Before I was treated, all I did was think about sleep. I rearranged my schedule so I could sleep. On the weekends I never wanted to go anywhere because I knew I had a finite amount of energy and when it was gone I would have to nap. I was always planning how I could sleep and when I could sleep and where I could sleep. But I never talked to people about the problem because I was embarrassed by it and because people misinterpreted my sleepiness as laziness. Plus I come from a family of workaholics, and I always thought fatigue and sleepiness came from overworking and overachieving. It never occurred to me I could have a disease. “Now that I’ve been treated, I keep to a strict sleep regimen. And it’s so wonderful to wake up feeling refreshed and not think that it’s a tragedy that my sleep is over. I don’t have to have my entire life revolve around sleep any longer.” |

regulating region of the hypothalamus and the brain stem. Researchers believe that hypocretin is critical for promoting and maintaining wakefulness during the day.

Narcolepsy can affect both men and women and can develop at any age—I’ve treated patients as young as 6 and as old as 82. However, the peak age of onset is during the teens and early 20s, so narcolepsy should certainly be considered during an evaluation of excessive teen sleepiness. If left untreated, it can significantly impair all aspects of a patient’s daily life. Patients who weren’t diagnosed until their 30s or later often say that their sleepiness kept them from achieving both their academic and social potential.

What would make you suspect narcolepsy? Sleepiness alone can be a very difficult symptom to evaluate in a teen because there are so many reasons for teens to be sleepy. Certainly evidence of cataplexy would be diagnostic, but episodes of reduced muscle tone may not be an issue for young people at all and adults often have fairly subtle signs of cataplexy because they subliminally blunt their emotions to avoid

the extremes that cause severe weakness. Classic cataplexy is seen when a narcoleptic person laughs at a very funny joke and crumples to the floor. But such an obvious manifestation is rare. A much more typical manifestation was evidenced in a patient of mine. Each time she was called to her rather stern boss’s office, she’d get halfway through her doorway and her knees would start to buckle—she’d have to stop and regroup.

Subtle evidence of cataplexy can also show up as a weakness in the shoulders or jaw. After laughing for a few seconds, your jaw muscle might get tired and you might not be able to laugh any longer, or your head might sag for a moment. Headaches are also a red flag for possible narcolepsy. Continuing and extreme sleepiness is also something to watch out for, though as I’ve said sleepiness is symptomatic of many sleep-related issues. As with other sleep disorders, you’ll need to first determine if there are underlying physical or emotional causes for your teen’s sleepiness, aggressively treat any elements of DSPS, have your teen catch up from any accumulated sleep debt, and then have her do a sleep study and a daytime nap study.

|

IT’S A FACT A family history of narcolepsy should also raise the possibility of narcolepsy in your sleepy teen if she doesn’t improve after increasing total sleep time and adjusting the sleep-wake schedule. |

If narcolepsy is the diagnosis, what are the possible treatments? The first step is to make sure your teen is getting at least the minimum number of hours of nighttime sleep; even though that sleep doesn’t relieve sleepiness, it’s needed for energy to get through the day. Naps can be helpful, too, though teens should keep them to no more than 20 to 30 minutes and finish them before 6:00 p.m.; they can help teens feel refreshed for the three to four hours following.

Treatment can include the use of wakefulness-promoting drugs such as Modafinil, a nonamphetamine-based compound that improves alertness by supporting the brain’s sleep-wake switch and increasing

hypocretin. Other standard medications include long- and short-acting methylphenidate derivatives and dextroamphetamine derivatives. Cataplexy in teens is rarely severe enough to require treatment wth drugs.

If your teen needs to take one of the stimulant medications, you may need to speak to her school administrator if she needs to receive a midday dose at school. You or your teen may also need to educate teachers and friends about the possible occurrence of cataplexy if your teen exhibits it.

Restless Legs Syndrome

There’s not a lot known about restless legs syndrome (RLS) in kids, though a fair number of adults who have it say that their symptoms first appeared in late childhood or adolescence. But the disorder can make those who have it very uncomfortable. It’s characterized by an overwhelming urge to move your limbs, especially your legs, usually beginning at bedtime when you’re lying quietly waiting for sleep. You get a creepy, crawly sensation in the calves of your legs—some of my patients call it a building tension—that ends in the urgent need to move them. You also might make a jerky movement with your feet or sometimes a stretching movement. Moving relieves the uncomfortable feeling—many patients resort to pacing—but tension begins to build again almost immediately, ending in another movement in as little as 20 seconds.

Because RLS symptoms often occur when you’re ready to sleep, they can impair your ability to relax and transition into sleep. The symptoms may also continue as periodic limb movements while you sleep, causing microarousals during sleep and resulting in daytime sleepiness. Patients who have severe RLS may have symptoms earlier in the evening or even during the daytime when sitting quietly, which can make it torture to read, go to the movies, or drive for a long time.

What causes RLS? Unfortunately, the precise mechanism isn’t known. However, Chris Early, a neurologist and sleep expert at Johns Hopkins, recently observed a relationship between RLS and low and low-normal serum iron levels (iron is a critical element of pathways involved in controlling and executing movement). Dr. Early has also

observed an improvement in some patients when body iron stores were replenished. Other studies have found a relationship between RLS and diseases of the peripheral nerves and spinal cord, kidney failure, dialysis, pregnancy, Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative conditions, and alcoholism. RLS can also occur as a side effect of some medications, particularly SSRIs, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which are prescribed for depression. Researchers from Stanford University’s School of Medicine have reported that about half of the 10 to 15 percent of the population who suffer from RLS have a family member with a history of the disorder, providing evidence that they inherited it.

|

IT’S A FACT If you have RLS, the National Sleep Foundation warns that your symptoms can become more severe if you consume caffeine or take antidepressants. |

While a diagnosis of RLS in kids is made very infrequently, if your teen is excessively tired and you’ve seen involuntary movements or your teen has complained of discomfort in her legs or arms and the need to move them, be sure to mention the symptoms to your daughter’s doctor. A history of building discomfort in the limbs that is relieved by movement helps distinguish a sleepy teen with DSPS from one with RLS. The doctor should see if an underlying condition exists—iron levels should definitely be checked—or if any medication the teen is taking precipitated or is aggravating the condition (a trial of a lower dose, a dose taken earlier in the day, or an alternative medication may be in order). You don’t want to neglect the problem when relief is available.

That relief may come in the form of different kinds of behavioral interventions, such as gentle stretches or yoga exercises in the evening. Some patients have reported that a warm bath or shower can be beneficial. Adult patients may get relief by drinking a glass of quinine water, but I know of no information about the chronic use of quinine water in teens. Boosting potassium stores with orange juice or a ba-

nana in the evening also may have some effect, though most likely it won’t improve full-blown RLS symptoms.

Sometimes, though we prefer to avoid it with teens, successful treatment requires the use of medication. Drugs that increase brain dopamine, gamma-amino-butyric acid, opioids, and newer-generation anticonvulsants may relieve symptoms. I use anticonvulsants for teens whose symptoms are severe enough to warrant intervention (there is precedent for using these drugs with teens for seizures). There is no increased risk to RLS patients of having any of the disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease and epilepsy, that these drugs are usually used to treat.

Insomnia

Though RLS is found infrequently in teens, the sleep disorder insomnia is much more prevalent. According to a report presented at the Associated Professional Sleep Societies’ annual meeting, one-third of the 1,014 teenagers who were interviewed for a study said they had had symptoms of insomnia at some point in their lives. A full 94 percent of those teens experienced insomnia symptoms at least twice a week for a month or longer, and 17 percent had full-blown insomnia that “caused noticeable distress and impaired their normal functioning.”

I think of insomnia as a symptom of a group of disorders rather than one disease. That’s because insomnia encompasses three different sleep problems:

-

Trouble falling asleep at night

-

Multiple awakenings during the night

-

Waking up too early in the morning

For teens the most common problem is falling asleep at night, but they also experience insomnia’s other difficulties.

When patients, especially teens, come to see me because they’re tired and are having trouble falling asleep, it can be difficult to sort out whether they have a delayed sleep phase or true sleep-onset insomnia. That makes it very important to take a careful history, because stress,

anxiety, and lack of a wind-down period in the evening can manifest in insomnia—they’re the most common causes of insomnia in teens. While some people respond to stress with stomachaches and by overeating—I get a crick in my neck—many people find that stress greatly disturbs their ability to fall asleep. They lie in bed and worry and either can’t fall asleep or wake up later in the night when they don’t want to.

When anxiety and stress dissipate, however, as the problem gets solved, most people move on and return to a regular sleep pattern after just a few sleep-restricted nights. But for other, more susceptible people, the stress-induced insomnia becomes a terrible pattern. Though the stressor goes away, these people continue to associate their bed, where they laid awake worrying, as a place to continue to lie awake and worry—and not sleep. Like Pavlov’s dog, who learned to salivate at the ring of a bell that accompanied food—a conditioned response— they become conditioned to getting into bed and having trouble falling asleep. This form of insomnia is called chronic psycho-physiological insomnia.

To help figure out whether a teen has insomnia or a shifted circadian rhythm, it’s very helpful to know what time she wakes up. While late sleep-ins are the hallmark of DSPS, a teen with insomnia tends to feel tired during the day but wakes up at an appropriate time in the morning. And unlike kids with a delayed sleep phase, teens with insomnia are usually not impossible to wake up.

It’s also important to find out what teens are doing at night. Can they not fall asleep because they just watched a violent TV show? Did they stay up very late talking to a friend? Did they eat a huge snack or exercise just before getting in bed? Are they worrying about something or maybe showing signs of depression? If stress or anxiety appears to be what’s keeping your teen awake, the first thing to do is to encourage your teen to talk about what’s bothering her with you, a trusted friend, teacher, or counselor. Many problems are tough for teens to solve on their own.

There are also several behavioral therapies that teens can use to keep stress from ruining their sleep. One is to stay out of bed until they’re truly tired enough to sleep. Keeping a sleep log will help identify when your teen actually falls asleep, and then she can wait until

approximately that time to get into bed. (If it gets too late, resulting in not enough sleep time, your teen can slowly move bedtime earlier after getting into a pattern of falling asleep more easily.) You can also suggest that your teen make some changes to make being in bed a different experience; this will help break the association between being in bed and not sleeping. Rearranging the bedroom, changing rooms with a sibling, or sleeping with their feet at the head of the bed are all ways to create a more positive sleep experience.

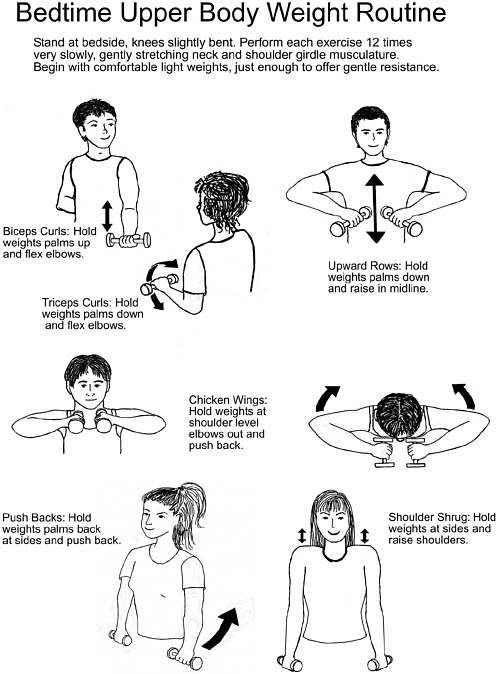

Stretching before bed is also a great way to de-stress. Teens can use the routine I recommend (see below) or develop their own set of easy stretches to help them wind down. As I suggested in Chapter 8, teens can also flush to paper: make lists of things that are bugging them, describe troublesome events to help them see another perspective, express wishes or dreams. Listing things they need to do can help them feel more organized and less anxious.

A great tool for getting your mind off your worries is called guided imagery. The idea is to picture a place and an experience you love and relive it—in multisensory, technicolor detail—in order to keep your mind focused on something pleasant and relaxing rather than on something worrisome or stress inducing. Since I love the beach, I relive the sights and sounds of the shore: waking up in a different bed, listening to the sounds of the apartment, going out on the balcony and looking at the early runners on the beach, listening to the ocean, feeling the sun. Then I recall typical beach day events: walking to the bagel shop for breakfast supplies, making sandwiches—who’s helping and what we’re making—packing the cooler with beach-specific junk food. I also recall the texture of the damp sand on the aluminum frame of the lawn

|

One Teen Says … “When I can’t fall asleep because I’m stressing about something, I close my eyes and picture a big stop sign. I use the sign to stop myself from going over and over my problem. Then I replace the sign with something relaxing or pretty, like some candles or the lake where I go.” |

chairs when I pick them up and stepping out of the building into the sun and the heat. I reach into my memory bank and remember every possible detail. It’s a great way to relax and enjoy a positive experience all over again.

Solving the problem of insomnia manifested as multiple wake-ups is a little more difficult, because when you’re asleep, of course, you can’t use behavioral remedies. The first thing to do is to make sure there are no external causes of the problem, such as the room being too hot, having eaten a late dinner, noise from elsewhere in the household, or having a pet in the bed. Then a careful history should be taken, looking for signs of health-related conditions, such as sleep apnea, RLS, heartburn, or continuing effects from daytime medications, that could be the cause. Since depression is strongly linked to multiple unwanted awakenings, it’s also important to rule it out.

SNOOZE NEWS

Major life stressors can also be a cause of multiple and early morning wake-ups. The worries of the day can disrupt sleep between 2:00 and 5:00 a.m—3:00 is a particularly fragile time for sleep—and it can be particularly difficult to fall soundly back to sleep afterward. Weeks of early morning awakenings and insufficient sleep time are signals that help is needed. Screening for depression and anxiety disorders, and treating them, is critical.

While behavioral strategies are extremely effective for managing sleep-onset insomnia, and should be the first line of treatment, they may be less effective for treating multiple nighttime and early morning awakenings. Sleep studies may be needed to evaluate for nocturnal sleep disorders. At times medication may be a reasonable source of relief for these problems, especially extended release hypnotics and selected antidepressants and anticonvulsants. Care needs to be taken, however, when selecting the appropriate drug: Some of these medications promote wakefulness. You’ll need to work with your teen’s doctor to discover which drug provides relief but, very importantly, you should also continue to use behavioral interventions to minimize prescription drug use.