Physical inactivity is a key determinant of health outcomes across the life span. A lack of activity increases the risk of heart disease, colon and breast cancer, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, osteoporosis, anxiety and depression, and other diseases. Recent studies have found that in terms of mortality the global population health burden of physical inactivity approaches that of cigarette smoking and obesity. Indeed, the prevalence of physical inactivity, along with this substantial associated disease risk, has been described as a pandemic.

Although complete data are lacking, the best estimate in the United States is that only about half of youth meet the current and evidence-based guideline of at least 60 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity daily. Moreover, the proportion of youth who meet this guideline declines with advancing age, so that younger children are more likely to do so than adolescents. Further, daily opportunities for incidental physical activity have declined for children and adolescents, as they have for adults, as a result of such factors as increased reliance on nonactive transportation, automation of activities of daily living, and greater opportunities for sedentary behavior. Finally, substantial disparities in opportunities for physical activity exist across racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic lines.

Perhaps it should not be surprising, then, that over the past 30 years the United States has experienced a dramatic increase in the prevalence of noncommunicable diseases, including obesity, many of which have their origins in childhood and persist as health burdens throughout adulthood. In examining this critical national health challenge, it becomes clear that increased physical activity should be an essential part of any solution.

The prevalence and health impacts of physical inactivity, together with evidence indicating its susceptibility to change, have resulted in calls for action aimed at increasing physical activity across the life span. Clearly, the earlier in life this important health behavior can be ingrained, the greater the impact will be on lifelong health. The question becomes, then, how physical activity among children and adolescents can be increased feasibly, effectively, and sustainably to improve their health, both acutely and throughout life. A recent report of the Institute of Medicine (IOM), Accelerating Progress in Obesity Prevention: Solving the Weight of the Nation, singles out schools as “a focal point for obesity prevention among children and adolescents,” stating: “Children spend up to half their waking hours in school. In an increasingly sedentary world, schools therefore provide the best opportunity for a population-based approach for increasing physical activity among the nation’s youth.”

STUDY APPROACH

In this context, the IOM’s Committee on Physical Activity and Physical Education in the School Environment was formed to review the current status of physical activity and physical education in the school environment (including before, during, and after school) and to examine the influences of physical activity and physical education on the short- and long-term physical, cognitive and brain, and psychosocial health and development of children and adolescents. The committee’s statement of task is provided in Box S-1.

The committee recognized that, although schools are a necessary part of any solution to the problem of inadequate physical activity among the nation’s youth, schools alone cannot implement the vast changes across systems required to achieve a healthy and educated future generation. Many more institutional players and supports will be necessary to make and sustain these changes. In approaching this study, therefore, the committee employed systems thinking to delineate the elements of the overall system of policies and regulations at multiple levels that influence physical activity and physical education in the school environment.

THE EVIDENCE BASE

Extensive scientific evidence demonstrates that regular physical activity promotes growth and development in youth and has multiple benefits for physical, mental, and cognitive health. Quality physical education, whereby students have an opportunity to learn meaningful content with appropriate instruction and assessments, is an evidence-based recommended strategy for increasing physical activity.

BOX S-1

Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) will review the current status of physical activity and physical education in the school environment. The committee will also review influences of physical activity and physical education on the short- and long-term physical, cognitive and brain, and psychosocial health and development of children and adolescents. The committee will then, as appropriate, make recommendations regarding approaches for strengthening and improving programs and policies for physical activity and physical education in the school environment, including before, during, and after school.

In carrying out its task, the committee will

• Review the current status of physical activity and physical education in the school environment.

• Review evidence on the relationship between physical activity, physical education, or physical fitness and physical, cognitive and brain, and psychosocial health and development.

• Within a life-stage framework, consider the role of physical activity and physical education-related programs and policies offered in the school environment in contributing to short- and long-term health, health behaviors, and development (e.g., motor and cognitive development).

• Recommend, as appropriate, strategic programmatic, environmental, and policy approaches for providing, strengthening, and improving physical activity and physical education opportunities and programs in the school environment, including before, during, and after school.

• As evidence is reviewed, identify major gaps in knowledge and recommend key topic areas in need of research.

Much of the evidence to date relating physical activity to health comes from cross-sectional studies showing associations between physical activity and aspects of physical health; nonetheless, the available observational prospective data support what the cross-sectional evidence shows. Conducting exercise training studies with young children is very challenging, so experimental evidence for the effects of physical activity on biological, behavioral, and psychosocial outcomes is limited for this population. It has been shown, however, that older children, especially adolescents, derive much the same health benefits from physical activity as young adults.

In addition to long-term health benefits, an emerging literature supports acute health benefits of physical activity for children and adolescents. Physical activity in children is related to lower adiposity, higher muscular strength, improved markers of cardiovascular and metabolic health, and higher bone mineral content and density. Physical activity in youth also can improve mental health by decreasing and preventing conditions such as anxiety and depression and enhancing self-esteem and physical self-concept.

Although evidence is less well developed for children than adults, a growing body of scientific literature indicates a relationship between vigorous- and moderate-intensity physical activity and the structure and functioning of the brain. Both acute bouts and steady behavior of vigorous-and moderate-intensity physical activity have positive effects on brain health. More physically active children demonstrate greater attentional resources, have faster cognitive processing speed, and perform better on standardized academic tests. Of course, academic performance is influenced by other factors as well, such as socioeconomic status, and understanding of the dose-response relationship among vigorous- and moderate-intensity physical activity, academic performance, and classroom behavior is not well developed. Nevertheless, the evidence warrants the expectation that ensuring that children and adolescents achieve at least the recommended amount of vigorous- and moderate-intensity physical activity may improve overall academic performance.

THE ROLE OF SCHOOLS

The evidence base summarized above supports the need to place greater emphasis on physical activity and physical education for children and adolescents, particularly on the role schools can play in helping youth meet physical activity guidelines.

Physical education has traditionally been the primary role played by schools in promoting physical activity. Despite the effectiveness of quality physical education in increasing physical activity, challenges exist to its equitable and effective delivery. Fiscal pressures, resulting in teacher layoffs or reassignments and a lack of equipment and other resources, can inhibit

the provision of quality physical education in some schools and districts. Schools may lack trained physical educators, and safety issues are associated with allowing children to play. Policy pressures, such as a demand for better standardized test scores through increased classroom academic time, further challenge the role of school physical education in providing physical activity for youth. Nearly half (44 percent) of school administrators report cutting significant amounts of time from physical education, art, music, and recess to increase time in reading and mathematics since passage of the No Child Left Behind Act in 2001. These challenges have been cited as reasons why the percentage of American schools offering physical education daily or at least 3 days each week declined dramatically between 2000 and 2006.

Children and adolescents engage in different types and patterns of physical activity as the result of a variety of factors, including age and access to resources. Exercise capacity in children and the activities in which they can successfully engage change in a predictable way across developmental periods. Young children are active in short bursts of free play, and their capacity for continuous activity increases as they grow and mature. In adults and likely also adolescents, improved complex motor skills allow for more continuous physical activity, although intermittent exercise offers much the same benefit as continuous exercise when the type of activity and energy expenditure are the same. Although the health benefits of sporadic physical activity at younger ages are not well established, children require frequent opportunities for practice to develop the skills and confidence that promote ongoing engagement in physical activity. Physical education curricula are structured to provide developmentally appropriate experiences that build the motor skills and self-efficacy that underlie lifelong participation in health-enhancing physical activity, and trained physical education specialists are uniquely qualified to deliver them.

In the best-possible scenario, however, physical education classes are likely to provide only 10-20 minutes of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity per session. Physical education, then, although important, cannot be the sole source of the at least 60 minutes per day of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity recommended to enhance the health of children and adolescents. Other ways to promote physical activity in youth must therefore be systematically exploited to provide physical activity opportunities. Family, neighborhood, and community programs can be a source of such additional opportunities. Moreover, other school-based opportunities, including intramural and extramural sports programs, active transport to and from school, classroom physical activity breaks, recess, and before- and after-school programming, all can help youth accumulate the recommended 60 or more minutes per day of physical activity while in the school environment. Yet educators and policy makers may lack awareness and understanding of how physical activity may improve academic

achievement and the many ways in which physical activity can and has been successfully incorporated into the school environment.

Traditionally, schools have been central in supporting the health of their students by providing immunizations, health examinations and screening, and nutrition programs such as school breakfasts and lunches, in addition to opportunities for physical activity. They also have acted as socioeconomic equalizers, offering all students the same opportunities for improved health through these services and programs. Moreover, local, state, and national policies have been able to influence what schools do. Given that children spend up to 7 hours each school day in school and many attend after-school programs, it is important to examine the role schools can play in promoting physical activity in youth. Although more physical activity at home and in the community is an important goal as well, the opportunity to influence so many children at once makes schools an extremely attractive option for increasing physical activity in youth.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee formulated recommendations in six areas: taking a whole-of-school approach, considering physical activity in all school-related policy decisions, designating physical education as a core subject, monitoring physical education and opportunities for physical activity in schools, providing preservice training and professional development for teachers, and ensuring equity in access to physical activity and physical education.

Taking a Whole-of-School Approach

Recommendation 1: District and school administrators, teachers, and parents should advocate for and create a whole-of-school approach to physical activity that fosters and provides access in the school environment to at least 60 minutes per day of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity more than half (>50 percent) of which should be accomplished during regular school hours.

- School districts should provide high-quality curricular physical education during which students should spend at least half (≥50 percent) of the class time engaged in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity. All elementary school students should spend an average of 30 minutes per day and all middle and high school students an average of 45 minutes per day in physical education class. To allow for flexibility in curricu-

- lum scheduling, this recommendation is equivalent to 150 minutes per week for elementary school students and 225 minutes per week for middle and high school students.

- Students should engage in additional vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity throughout the school day through recess, dedicated classroom physical activity time, and other opportunities.

- Additional opportunities for physical activity before and after school hours, including but not limited to active transport, before- and after-school programming, and intramural and extramural sports, should be made accessible to all students.

Because the vast majority of youth are in school for many hours, because schools are critical to the education and health of children and adolescents, and because physical activity promotes health and learning, it follows that physical activity should be a priority for all schools, particularly if there is an opportunity to affect academic achievement. As noted earlier, schools have for years been the center for other key health-related programming, including screening, immunizations, nutrition, and substance abuse programs. Unfortunately, school-related physical activity has been fragmented and varies greatly across the United States, within states, within districts, and even within schools. Physical education typically has been relied on to provide physical activity as well as curricular instruction for youth; as discussed above, however, physical education classes alone will not allow children to meet the guideline of at least 60 minutes per day of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity. Interscholastic and intramural sports are another traditional opportunity for physical activity, but they are unavailable to a sizable proportion of youth. Clearly schools are being underutilized in the ways in which they provide opportunities for physical activity for children and adolescents. A whole-of-school approach that makes the school a resource to enable each child to attain the recommended 60 minutes or more per day of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity can change this situation.

The committee therefore recommends a whole-of-school approach to physical activity promotion. Under such an approach, all of a school’s components and resources operate in a coordinated and dynamic manner to provide access, encouragement, and programs that enable all students to engage in vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity 60 minutes or more each day. A whole-of-school approach encompasses all segments of the school day, including travel to and from school, school-sponsored before- and after-school activities, recess and lunchtime breaks, physical education classes, and classroom instructional time. Beyond the resources

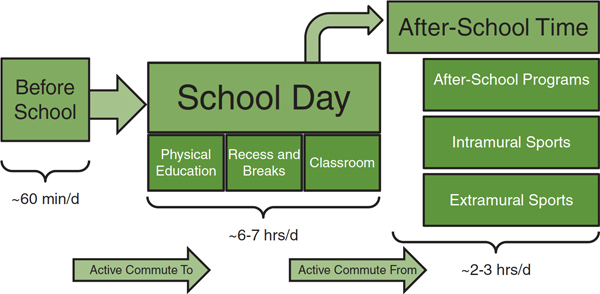

FIGURE S-1 A whole-of-school approach.

SOURCE: Beets, 2012. Reprinted with permission from Michael Beets.

devoted to quality daily physical education for all students, other school resources, such as classroom teachers, staff, administrators, and aspects of the physical environment, are oriented toward physical activity. Intramural and extramural sports programs are available to all who wish to participate, active transport is used by substantial numbers of children to move from home to school and back again, recess and other types of breaks offer additional opportunities for physical activity, and lesson plans integrate physical activity as an experiential approach to instruction. Figure S-1 illustrates the breadth of opportunities available for physical activity in the school environment.

A whole-of-school approach encompasses all people involved in the day-to-day functioning of a school, including students, faculty, staff, and parents. It creates an atmosphere in which physical activity is appreciated and encouraged by all these groups. School buildings, outdoor grounds and playgrounds, indoor and outdoor equipment, and streets and pathways leading to the school from the surrounding neighborhood encourage and enable all persons to be more physically active. Moreover, the school is part of a larger system that encompasses community partnerships to help these goals be realized.

Considering Physical Activity in All School-Related Policy Decisions

Recommendation 2: Federal and state governments, school systems at all levels (state, district, and local), city governments and city planners, and parent-teacher organizations should systematically consider access to and provision of physical activity in all policy decisions related to the school environment as a contributing factor to improving academic performance, health, and development for all children.

Many examples exist of effective and promising strategies for increasing vigorous- and moderate-intensity physical activity in schools. The most thorough yet often most difficult to implement are multicomponent interventions based on a systems approach that encompasses both school and community strategies. For strategies with a singular focus, the evidence is most robust for interventions involving physical education. Although physical education curricula should not focus only on physical activity, those curricula that do emphasize fitness activities result in more physical activity. Quality physical education curricula increase overall physical activity, increase the intensity of physical activity, and potentially influence body mass index (BMI) and weight status in youth. However, the lack of consistent monitoring of physical activity levels during physical education classes in schools (especially elementary and middle schools) impedes monitoring and evaluation of progress toward increasing physical activity during physical education classes in schools across the nation (see Recommendation 4).

Beyond physical education, opportunities for increasing physical activity are present both in the classroom and, for elementary and middle schools, during recess. Classroom physical activity and strategies to reduce sedentary time in the school setting hold promise for increasing overall physical activity among children and adolescents, yet isolating the impact of these strategies is complex, and they are often met with resistance from key stakeholders. With respect to recess, its use to increase physical activity is a nationally recommended strategy, and there is evidence that participating in recess can increase physical activity and improve classroom behavior. However, implementation of recess across school districts and states is not currently at a sufficient level to increase physical activity.

Effective and promising strategies beyond the school day include after-school programming and sports, as well as active transport to and from school. After-school programming and participation in sports are important physical activity opportunities in the school setting, but implementation of and access to these opportunities vary greatly. Moreover, formal policies adopting physical activity standards for after-school programs are needed. Finally, evidence shows that children who walk or bike to school are more

physically active than those who do not. Successful active transport interventions address policy and infrastructure barriers.

Also associated with the school environment are agreements between schools and communities to share facilities as places to be physically active. Although this is a relatively new research topic, these joint-use agreements can be a way to give youth additional opportunities for physical activity outside of school. Further research is needed on utilization of facilities resulting from such agreements and their impact on physical activity.

Designating Physical Education as a Core Subject

Recommendation 3: Because physical education is foundational for lifelong health and learning, the U.S. Department of Education should designate physical education as a core subject.

Physical education in school is the only sure opportunity for all school-aged students to access health-enhancing physical activity and the only school subject area that provides education to ensure that students develop the knowledge, skills, and motivation to engage in health-enhancing physical activity for life. Yet states vary greatly in their mandates with respect to time allocated for and access to physical education. As stated previously, 44 percent of school administrators report having cut significant time from physical education and recess to increase time devoted to reading and mathematics in response to the No Child Left Behind Act. Moreover, while the literature on disparities in physical education by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status is limited and not always as straightforward, disparities have been documented in access to physical education for students of Hispanic ethnicity and lower socioeconomic status.

Currently, despite growing concern about the negative consequences of physical inactivity, physical education is not considered or treated as a core subject. Several national studies and reports have pointed to the importance of implementing state laws and regulations mandating both time requirements for physical education and monitoring of compliance with those requirements. Although a number of national governmental, nongovernmental, private industry, and public health organizations and agencies have offered specific recommendations for the number of days and minutes per day of physical education, no policy that is consistent from state to state has emerged. If treated as a core academic subject, physical education would receive much-needed resources and attention, which would enhance its overall quality in terms of content offerings, instruction, and accountability. Enactment of this recommendation would also likely result in downstream accountability that would assist in policy implementation.

Monitoring Physical Education and Opportunities for Physical Activity in Schools

Recommendation 4: Education and public health agencies at all government levels (federal, state, and local) should develop and systematically deploy data systems to monitor policies and behaviors pertaining to physical activity and physical education in the school setting so as to provide a foundation for policy and program planning, development, implementation, and assessment.

The intent of this recommendation is to give citizens and officials concerned with the education of children in the United States—including parents and teachers as well as education and public health officials at the local, state, and federal levels—the information they need to make decisions about future actions. Principals, teachers, and parents who know that regular vigorous- and moderate-intensity physical activity is an essential part of the health and potentially the academic performance of students and who have adopted a whole-of-school approach to physical activity will want and need this information. This information also is important to support the development of strategies for accountability for strengthening physical activity and physical education in schools.

Aside from a few good one-time surveys of physical activity during physical education classes, remarkably little information is available on the physical activity behaviors of students during school hours or school-related activities. Even the best public health monitoring systems do not collect this information. This dearth of information is surprising given that school-related physical activity accounts for such a large portion of the overall volume of physical activity among youth and that vigorous- and moderate-intensity physical activity is vital to students’ healthy growth and development and may also influence academic performance and classroom behavior.

The few existing monitoring systems for school-related physical activity behaviors need to be augmented. Information is needed not only on the amount of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity in which youth are engaged but also on its distribution across segments of the school day (i.e., physical education, recess, classroom, travel to and from school, school-related before- and after-school activities). Existing national surveys are not designed to provide local or even state estimates of these student behaviors. State departments of education, local school districts, and state and local health departments will need to collaborate to provide adequate monitoring. Also needed is augmented monitoring of physical activity– related guidelines, policies, and practices at the federal, state, and local levels.

Evidence is emerging that laws and policies at the state and district levels have not just potential but actual influence on the physical activity behaviors of large numbers of children and adolescents. Also emerging is evidence of a gap between the intent and implementation of policies, so that their final impact is commonly less, sometimes appreciably so, than expected. While the factors that create an effective policy are still being elucidated, policies that entail required reporting of outcomes, provision of adequate funding, and easing of competing priorities appear to be more likely to be implemented and more effective. Further evaluation of physical activity and physical education policies is needed to fully understand their impact in changing health behavior.

Monitoring of state and district laws and policies has improved over the past decade. In general, the number of states and districts with laws and policies pertaining to physical education has increased, although many such policies remain weak. For example, most states and districts have policies regarding physical education, but few require that it be provided daily or for a minimum number of minutes per week. Those that do have such requirements rarely have an accountability system in place. Although some comprehensive national guidelines exist, more are needed to define quality standards for policies on school-based physical activity and to create more uniform programs and practices across states, school districts, and ultimately schools.

Providing Preservice Training and Professional Development for Teachers

Recommendation 5: Colleges and universities and continuing education programs should provide preservice training and ongoing professional development opportunities for K-12 classroom and physical education teachers to enable them to embrace and promote physical activity across the curriculum.

Teaching physical education effectively and safely to youth requires specific knowledge about their physical/mental development, body composition (morphology) and functions (physiology and biomechanics), and motor skills development and acquisition. Teaching physical education also requires substantial knowledge and skill in pedagogy, the science and art of teaching, which is required for any subject. In addition, because health is associated with academic performance, priority should be given to educating both classroom and physical education teachers about the importance of physical activity for the present and future physical and mental health of children.

The current wave of effort to curb childhood physical inactivity has begun to influence teacher education programs. Data appear to suggest that training programs for physical education teachers are beginning to evolve from a traditionally sport- and skill-centered model to a more comprehensive physical activity– and health-centered model. However, education programs for physical education teachers are facing a dramatic decrease in the number of kinesiology doctoral programs offering training to future teacher educators, in the number of doctoral students receiving this training, and in the number of professors (including part-time) offering the training. Additional data suggest a shortage of educators in higher education institutions equipped to train future physical education teachers. With unfilled positions, these teacher education programs are subject to assuming a marginal status in higher education and even to being eliminated.

Professional development—including credit and noncredit courses, classroom and online venues, workshops, seminars, teleconferences, and webinars—improves classroom instruction and student achievement, and data suggest a strong link among professional development, teacher learning and practice, and student achievement. The most impactful statement of government policy on the preparation and professional development of teachers was the 2002 reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. Although Title I of the act places highly qualified teachers in the classroom, Title II addresses the same goal by funding professional development for teachers. According to the No Child Left Behind Act, professional development should be offered to improve teachers’ knowledge of the subject matter they teach, strengthen their classroom management skills, advance their understanding and implementation of effective teaching strategies, and build their capabilities to address disparities in education. This professional development should be extended to include physical education instructors as well.

Ensuring Equity in Access to Physical Activity and Physical Education

Recommendation 6: Federal, state, district, and local education administrators should ensure that programs and policies at all levels address existing disparities in physical activity and that all students at all schools have equal access to appropriate facilities and opportunities for physical activity and quality physical education.

All children should engage in physical education and meet the recommendation of at least 60 minutes per day of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity regardless of their region, school attended, grade level, or

individual characteristics. However, a number of studies have documented social disparities in access to physical education and other opportunities for physical activity by race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, and immigrant generation. Moreover, because not every child has the means or opportunity to participate in before- and after-school activities and intramural/extramural sports, curriculum-based physical education programs often provide the only opportunity for all school-aged children to access health-enhancing physical activity.

FUTURE RESEARCH NEEDS AND AREAS FOR ADDITIONAL INVESTIGATION

As stated at the beginning of this Summary, an extensive scientific literature demonstrates that regular physical activity promotes growth and development in children and adolescents and has multiple benefits for physical, mental, and cognitive health. Looking forward, gaps remain in knowledge about physical activity and physical education in the school environment and key areas in which research would be useful to those who are implementing programs and policies designed to improve children’s health, development, and academic achievement. These research needs are covered in greater detail throughout the report and especially in the final chapter. They include topics such as

• the effects of varying doses, frequency, timing, intermittency, and types of physical activity in the school environment;

• the relationship between motor skills and participation in physical activity;

• baseline estimates of physical activity behaviors in school;

• standardized data on participation in physical education, including the degree of vigorous- or moderate-intensity physical activity in these classes;

• the extent and impact of sedentary behavior in school;

• the influence of school design elements;

• the impact of school-community physical activity partnerships;

• the impact of physical activity–related policies, laws, and regulations for schools; and

• the effectiveness of various physical activity–enhancing strategies in schools to address the needs of students who typically have not had equal access to opportunities for physical activity.