6

Title IX for Women in Academic Chemistry: Isn't a Millennium of Affirmative Action for White Men Sufficient?

Debra R. Rolison

Naval Research Laboratory

The subtitle of this talk—“Isn't a Millennium of Affirmative Action for White Men Sufficient?”—serves as an exercise in putting the shoe on the other foot. The first university, the University of Bologna, was established, according to its Web site, in 1088.1 The actual date is debatable because one has to decide when the “modern” university—as a forum for open discussion and as a place to seek new knowledge —arose out of the ecclesiastical schools; but the University of Bologna pegs its establishment at 1088. During most of the ensuing millennium, universities blatantly practiced preferential hiring: men only.2 It is only recently that the hiring preference has started to change.

One might ask if a millennium isn't enough time passed before we diversify our university system. In the United States, a country blessed with a highly educated, diverse populace and where the modern university, public and private, lives and breathes by federal taxpayer dollars, one can rightly ask, Should the American taxpayer still support institutions that continue to hire white men preferentially?

Dan Greenberg, who writes a column in the Washington Post, touched upon something very similar one year ago: “Universities claim to be sources of enlightenment and progress. Of course they are, but in important respects they are also retrograde institutions detached from a society that is increasingly resentful about their ways.”3 Greenberg had numerous “retrograde” examples, some of which were tied to the MIT report that was issued in 1999 describing discrimination against the senior women faculty in MIT's College of Science.4 Greenberg faulted U.S. universities, in general, for the slow progress of women's academic careers, especially in the sciences.

|

1 |

The history of the University of Bologna, including the presence of women scientists and legal scholars on its faculty during the Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment, can be traced on the university 's Web site, <http://www.unibo.it/avl/english/story/story.htm>. |

|

2 |

Unlike most European universities, the Italian universities, and especially the University of Bologna, did have women faculty before the 1800s, including the outstanding physicist Laura Bassi (see <http://www.unibo.it/avl/english/biogr/bio15.htm>), but the faculty remained predominantly male. |

|

3 |

Daniel S. Greenberg, “Where higher ed has it backward,” Washington Post, 8 June 1999, p. A19. |

|

4 |

“A study on the status of women faculty in science at MIT,” MIT Faculty Newsletter, March 1999, available at <http://web.mit.edu/fnl/women/women.html>. This article summarizes a 150-page unpublished report on the suject that was prepared in 1994. |

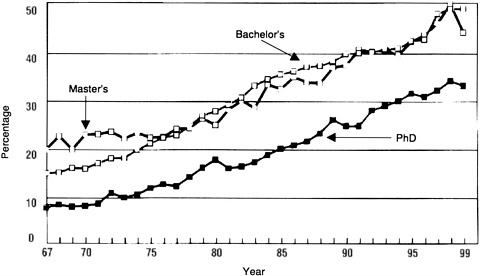

FIGURE 6.1 Percentage of chemistry degrees earned by women from 1967 to 1999. SOURCE: These figures are derived from the yearly starting salary surveys performed by the American Chemical Society. The figures for 1999 appeared in Chemical & Engineering News, March 13, 2000.

In a recent study of the paradox of the critical-mass issue,5 the authors cited a suggestion from B. Lazarus, a representative of WISE (Women in Science and Engineering), who advocated that the National Science Foundation (NSF) cut off grants to those universities that don't have a minimum number of female faculty in their science and engineering departments. That is a pretty drastic suggestion, but one can make it more drastic—cut off not just NSF funding but all federal funding.6

THE QUESTION UNDER CONSIDERATION

Should federal funds—not just NSF-derived, not just NIH (National Institutes of Health)-derived funds, but all federal funds—be withheld from those universities that do not increase their faculty hires to reflect the diversity of today's pool of U.S.-granted chemistry Ph.D.s?7 As seen in Figure 6.1, women composed one-third of that pool in 1999 and have been present at more than 20 percent since 1985. Despite that year-in, year-out production of talent, NSF reported in 1998 that only 12.5 percent of the senior faculty (associate and full professors) in the natural sciences and engineering at U.S. universities and 4-year colleges were women.8

|

5 |

Henry Etzkowitz, Carol Kemelgor, Michael Neuschatz, Brian Uzzi, and Joseph Alonzo, “The paradox of critical mass for women in science, ” Science, 1994, 266, 51. |

|

6 |

Debra R. Rolison, “A Title IX challenge,” Chemical & Engineering News, 13 March 2000, 78(11), p. 5. |

|

7 |

Debra R. Rolison, “A Title IX challenge,” Chemical & Engineering News, 13 March 2000, 78(11), p. 5. |

|

8 |

National Science Foundation. Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering: 1998. NSF 99-338, Arlington, VA, 1999. |

Is it time, in other words, to convince Congress (or the Judiciary) that the loss of federal funds can be a Title IX action against U.S. chemistry departments and their universities for their entrenched “inability” to hire women?

WHY TITLE IX?

The Education Amendments of 1972, commonly called Title IX, state in the first subsection (A: prohibition against discrimination): “No person in the United States shall on the basis of sex be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”9 I would argue being a professor in a federally funded university is an educational activity.

Subsection B, which discusses preferential or disparate treatment, includes language that states that Title IX cannot be used to discriminate. This subsection does permit, however, “the consideration in any hearing or proceeding under this chapter of statistical evidence tending to show that such an imbalance exists.”10 An imbalance exists, and has for over 15 years, between the fraction of women graduated with Ph.D.s in chemistry and the fraction of women who have applied and been hired for faculty openings in U.S. chemistry departments.

Now, Title IX is a very big hammer. I think a very plausible case can be made for using that hammer, but the laws usually applied to discriminatory work environments are those embodied in the Civil Rights Act and Equal Employment Opportunity legislation.11 This legal recourse means that one files a lawsuit against a specific workplace, and if the treatment is especially egregious, the lawsuit can be expanded to a class-action suit. Why not fight this problem —the acknowledged lack of women in the academic chemical workforce —through lawsuits taking one chemistry department at a time? My response is that women should not be asked to wage this campaign lawsuit by lawsuit by lawsuit, because that is a war of attrition—against the women. The system is broken. The women are not.

Here is an example of the futility of one-chemistry-department-at-a-time lawsuits. One of the best known examples in chemistry is the Rajender case at the University of Minnesota. Dr. Shyamala Rajender was performing the duties expected of tenure-track faculty in the university's Department of Chemistry, but the university refused to consider her for a tenure-track position. She filed a lawsuit in 1973, alleging sex discrimination. That lawsuit was expanded in 1975 to the entire University of Minnesota system on behalf of all academic, nonstudent, female employees of the university. In 1980, the university signed a consent degree that agreed to policy changes, the scope of which is said by legal experts to be unmatched in the higher education system.12

|

9 |

A list of exclusions, listed in subsection A of Title IX, includes certain exemptions for specific organizations, such as religious and vocational and (my favorite) beauty pageants. The Department of Labor's Web site, <http://www2.dol.gov/dol/oasam/public/regs/statutes/titlexi.htm>, describes Title IX in detail. |

|

10 |

See the Department of Labor's Web site, <http://www2.dol.gov/dol/oasam/public/regs/statutes/titlexi.htm>. |

|

11 |

Information on the federal laws, through Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, that prohibit employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, can be obtained at <http://www.eeoc.gov/facts/qanda.html>, the Web site for the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. |

|

12 |

Nijole Benokraitis and Joe R. Feagin, Modern Sexism: Blatant, Subtle and Covert Discrimination, 2nd ed. (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1995), available at <http://www.runet.edu/~Iridener/courses/getrid.html>. The Rajender case is also summarized on the Web site for the Minnesota Women's Center, <http://www1.umn.edu/mnwomen/mwchistory.html>. |

The decision against the University of Minnesota looks like a clear verdict that women were being discriminated against by the university. What was the outcome? A lot of money was spent: $7 million in 1980 dollars in legal fees and settlements, including $1.5 million to Rajender's lawyers. And the departmental faculty today? If you check the University of Minnesota's chemistry Web site13 and count the number of assistant, associate, and full professors —excluding the professors emeriti and colisted faculty—46 professors are listed, 3 of whom are women. The University of Minnesota lost that lawsuit badly, and 20 years later women represent only 6.5 percent of the faculty in the university's Department of Chemistry.

This is why I believe that fighting this fight one department at a time is brutality against the women involved.

FINALLY! ROOM IN THE ACADEMIC POOL—A HISTORIC OPPORTUNITY

Employment opportunities for Ph.D. scientists have only recently become healthy again, so until now women who wanted to go into academia had a very tight job market in which to try to make their way into that workforce. Today, all the people hired in the 1960s, during the boom years for expanding the scientific enterprise in this country, are nearing retirement or emeriti status. For the first time, there is room in the academic pool.

This egress and accompanying ingress of faculty offers the chemical sciences a historic opportunity. Faculty positions are opening up and will continue to do so for the next 5 to 10 years. Are we, as a profession, going to seize this opportunity or are we going to squander it? Will a woman-free (or woman-sparse) faculty be locked in for another generation? If the number of women on chemistry faculties is not substantially increased during this historic opportunity, every chemist in this country should be ashamed.

WHY ARE THE NUMBERS OF WOMEN ON CHEMISTRY FACULTIES SO LOW?

One clue emerges in the contrast between cocktail folklore and real statistics. When one talks to (primarily male) chemistry faculty at professional gatherings, one is usually told that 10 percent of the applications for a new faculty opening came from women. This number is pathetically low. Why is the applicant pool not 20 percent, 30 percent, or 33 1/3 percent female, when for every two men to whom we give a Ph.D. in chemistry in this country, there is one woman? Why does the applicant pool so poorly reflect the actual candidate pool that exists?

As Figure 6.1 reveals, since 1985, more than 20 percent of the Ph.D.s in chemistry in the United States went to women. That span of 15 years covers more than two tenure cycles. The women are there, and they have been there for years. Why are they not even applying for faculty positions? The language I like to use is that they are voting with their feet—voting against the university.

Graduate students working toward a Ph.D. constitute the pool of candidates that ultimately chooses for or against the university as a career home. These doctoral students have spent 4 to 6 years working hard, trying to master the craft of chemistry and trying to hone their chemical creativity. They have spent far less time or thought on how to create a career in chemistry. The one institution known with any certainty to them is academia. They know that chemists get jobs in industry, but do they really know how to make a career in industry? They know next to nothing about the government labs.

|

13 |

The Web site for the Department of Chemistry at the University of Minnesota can be found at <http://www.chem.umn.edu/directory>. |

The graduate students of today also do not know much about career possibilities in small entrepreneurial companies and dot-coms, but —then and now—graduate students do know academia. More and more, men and women—and the women more than the men—are saying, “No, thank you” to a life in academia. Why? To answer that, I have borrowed a list of reasons from the speaking package assembled by the Committee on the Advancement of Women Chemists, or COACh.14 Part of this list is a realistic look at why women might not want to go into academia; some of it is tongue-in-cheek, and by being tongue-in-cheek it is even more spot on. Are women choosing not to go into academia—are they voting against a university career—because:

-

The hours are long and the pay is low?

-

They don't want to serve on so many fascinating university committees, including every affirmative action committee ever constituted on campus?

-

They don't wish to compete for grants when receiving four Excellents and one Very Good means their proposal is dead?

-

They don't want to postpone having children until they have gained tenure? (Or, as one of my colleagues at the Naval Research Laboratory likes to say, until they are almost postmenopausal?)

-

They don't want to be role models for every young woman on campus and beyond? All too often being a role model means being a mentor and adviser not only to a disproportionate number of students—male and female —but also to male colleagues seeking a friendly and unthreatening ear.

Or is it, as one male chemist commented, because once again women have shown that they are smarter than men? Some things in this list are funny but true, and some are sad but true.

I want to expand on this aspect of role model and mentor. That role is an enormous burden on one's energy, and it is a burden that many women take on gladly; but one person really cannot mentor the planet. After I proposed, in an editorial in Chemical & Engineering News, that it was time to apply Title IX to chemistry departments and presented a truncated list of reasons why that was a rational proposal,15 I received reams of supportive e-mail from both men and women—students and faculty, as well as people in industry and government.

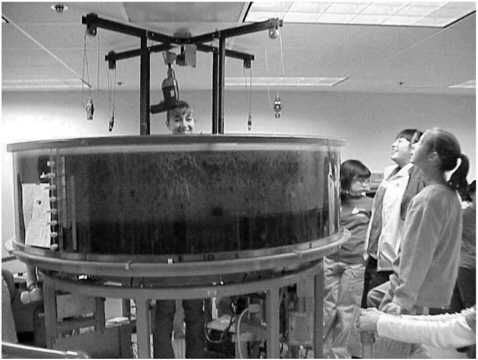

One of my electronic correspondents, Anna Farrenkopf, who is a postdoctoral researcher at the Oregon Graduate Institute, is also a leader in a mentoring program at OGI called Advocates for Women in Science, Engineering, and Mathematics (AWSEM). The AWSEM program brings young students to OGI over the course of the year, not just as a one-time event, to see how women do science: Anna and her compatriots have the students do experiments and show them what an exciting career science and engineering can provide.16 Some of Anna's science can be seen in Figure 6.2, in which the tank is actually a huge electrochemical cell containing a slice of the Columbia River. In this test bed, Anna has planted a microelectrode so that she can study the electrochemical properties of the sediment using a probe that has a characteristic dimension of about one micrometer.

|

14 |

The Committee on the Advancement of Women Chemists (COACh) exists to increase the number and effectiveness of women in research and leadership positions in the chemical sciences. Seed funding to establish the committee was provided by the Camille & Henry Dreyfus Foundation. For more information on COACh and implementation of its strategies to enhance the leadership effectiveness of women chemists (including development of job skills for women already established as associate and full professors), contact co-chairs Geraldine Richmond, of the University of Oregon, <richmond@oregon.uoregon.edu>, and Jeanne Pemberton, of the University of Arizona, <pembertn@u.arizona.edu>. |

|

15 |

Debra R. Rolison, “A Title IX challenge,” C&EN, 13 March 2000, 78(11), p. 5. |

|

16 |

When women discuss their science, it makes the point far better than almost anything else that women do great science. Our energy, quality, and devotion are an important message we transmit when, as women in science, we talk about our work. |

FIGURE 6.2 The rotating annular flume surrounded by Advocates for Women in Science, Engineering, and Mathematics students. Microelectrodes are used to track chemical changes (fate and transport) across the sediment-water interface subsequent to resuspension of the sediment; the microelectrodes are obscured in the flume by the suspended solids in the river water overlying the Columbia River sediment bed. Photo taken by middle-school science teacher Laurie Denio.

Anna, the postdoc, read my “Title IX” editorial and wrote: “Hi, Debra. You go, woman. Wow. That was quite an editorial. I made 100 copies and put it in all the faculty and postdoc boxes here at the Graduate Institute.” I asked her to give me some feedback since she had taken that initiative, and she wrote back, “Well, one of my male colleagues walked in with a copy of the editorial and said, ‘Anna, this is for you.' I looked at him and said, ‘No, I put it in your box.' ”

Dr. Farrenkopf then expanded on that disconnect, about what it means to be a woman surrounded by people who need such reminders from women. “Everywhere I go, I am told that working as a woman in science is my issue. It isn't one to be shared by all of my colleagues. It is mine alone.” Anna's observation gets back to the point that women continually have to make to men: Women alone aren't supposed to solve this problem. Women and men have to solve this problem.

Anna continued: “It is funny: the same folks who dismiss the women-in-science issue as pertaining exclusively to me are the folks who send me their graduate students, postdocs, and staff to mediate or consult with me when perceived or imagined issues of gender or gender equity get raised. I definitely know that I am not alone, for quite often my workday consists of supporting a network of contemporaries and younger men and women.” This level of mentorship is being asked of a postdoctoral researcher.

WHY ARE WOMEN VOTING WITH THEIR FEET AGAINST ACADEMIA?

In my view, women are the canaries in the mines.17 The fact that women are not applying for academic openings in proportion to their presence in the candidate pool tells you that our chemistry departments are not providing an environment in which a human being can grow and thrive.18

What if we take the relative absence of women in the faculty applicant pool as a tacit statement from women that chemistry departments are not healthy places for human beings? Universities and chemistry departments are, as Dan Greenberg said, “retrograde”19—they are missing representation from women and minorities and do not serve a modern society.

The current departmental environment is unhealthy in several ways:

-

Unhealthy for men and women who want children—and who want to play a meaningful role in their lives, not just give birth to or sire them;

-

Unhealthy to the women who, once they demonstrate productivity, scholarship, and mentorship, still reap less respect than their comparably productive colleagues and less of all those things that indicate that one has respect: awards, raises, extra space, the right kind of committees;20

-

Unhealthy to those men and women who want to create teams, who want to do collaborative, cooperative research rather than cutthroat research;

-

Unhealthy to those men and women who think that the reason they are in a university is to educate and mentor and guide students; and

-

Unhealthy to those undergraduate students who are trying to picture what their life will be like as a chemist, especially as a chemist in academia, when what they often see are people they have no desire to be like.

This list makes a perfectly sound case that chemistry departments, as we have configured them, are not healthy environments for human beings, and that is why the women are ignoring these departments as a career home.

If the absence of women from the applicant pool is the observable, what is the mechanism? I would postulate that the problem lies with departmental and scientific culture, which in turn exists within this huge bubble of our societal culture. Wolf-laureate Chien-Shiung Wu, a physicist who arguably should have gotten a Nobel Prize but didn't, addressed that point before she died: “I sincerely doubt that any open-minded person really believes in the faulty notion that women have no intellectual capacity for science and technology.21 Nor do I believe that social and economic factors are the actual obstacles that prevent women's participation in scientific and technical fields. The main stumbling block in the way of any progress is and always has been unimpeachable tradition.”22 This observation came from a

|

17 |

Debra R. Rolison, “A Title IX challenge,” C&EN, 13 March 2000, 78(11), p. 5. |

|

18 |

Joan Selverstone Valentine captured the essence of this problem ( Science 1992, 256, p. 1615) by telling young women: “Shun departments with a record of hostility to women (and to assistant professors in general), no matter how high those departments may stand in national rankings.” |

|

19 |

Daniel S. Greenberg, “Where higher ed has it backward,” Washington Post, 8 June 1999, p. A19. |

|

20 |

This manner of disrespect hearkens back to the MIT report (see footnote 4). Students and young research scientists are not unaware of the treatment of senior women staff and faculty. Until a few years ago, my postdoctoral associates at the Naval Research Laboratory said that there was no way they would consider an opening at NRL because of how I was treated relative to my male colleagues. |

|

21 |

Unfortunately, many women chemists could easily generate a list of men chemists who feel that women have no intellectual capacity for science, but we will give Professor Wu that part of her statement. |

woman who left Shanghai and Chinese culture for the West, so she knew something about unimpeachable tradition.

What has our tradition been? In Western science it has been, since day one, a world without women. David Noble wrote a book about that. 23 In fact, his book jacket shows Albrecht Dürer's very famous etching of Adam and Eve—without Eve. Noble had this glorious piece of Dürer's art retouched by Kathy Grove to take Eve out of the picture in order to symbolize, all too accurately, Western science.

Western science derived from the intellectual context of monasteries and ecclesiastical schools and then moved into the universities, retaining almost all the vestiges of its beginnings in the monastery. 24 The ideal was, and in some ways still is, that one is dedicated around-the-clock to the scholastic pursuit of knowledge, and to do that either one must be a monk (or exhibit monastic dedication) or have an infrastructure. For most of our recorded civilized history, that infrastructure has been a wife, or as Garvan Medalist Janet Osteryoung has mused, “Every professional needs a wife.”

It certainly is not an option most women have open to them in today 's world. What the university requires is disconnected from what modern society has become—a world with women and minorities. As members of a profession, we should step back and ask if we want one of the most rewarding paths of our profession to be off-limits to men and women because they want their personal, human priorities to be given a place, too.

That disconnect—between what was and what is—is a major problem. But the current environment in departments is a multivariate problem—improving the environment will require more than one solution, even if Title IX is probably the biggest hammer we can take to it.

COVERT RATHER THAN OVERT BIAS

Recently, Howard Georgi, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics at Harvard, enumerated a number of things that many people have said before, 25 but now a white male physicist is saying it: “Unconscious discrimination arises due to deep-seated habits that will be very hard to change,”26—much of which gets back to the in-built gender and racial schema of our species.27 Georgi continues: “Our selection procedures tend to select not only for talents that are directly relevant to success in science”—and one would hope that that includes brightness, creativity, the ability to persevere, and treating well those in our charge—“but also for assertiveness and single-mindedness. . . qualities that are at best very indirectly related to being a good scientist and that clash with cultural pressures. . . . It is not impossible to succeed as a scientist without being assertive and single-minded, but the system encourages and rewards people with these traits in a number of ways.”28

|

22 |

Sharon Bertsch McGrayne, Nobel Prize Women in Science, 2nd ed. (Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 1998), p. 279. |

|

23 |

David F. Noble, A World Without Women—The Christian Clerical Culture of Western Science (New York: Knopf, 1992). |

|

24 |

David F. Noble, A World Without Women—The Christian Clerical Culture of Western Science (New York: Knopf, 1992). |

|

25 |

For example, Elizabeth Zubritsky, “Women in analytical chemistry speak,” Anal. Chem. 2000, 72, 272A. |

|

26 |

Howard Georgi, “Is there unconscious discrimination against women in science?” APS News, 2000, 9(1), The Back Page, available at <http://www.aps.org/aspnews/0100/010016.html>; and Who Will Do the Science in the Future? (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 2000). |

|

27 |

Virginia Valian, “Running in place—After thirty years on the fast track, women are still hobbled by the cumulative effects of sexual stereotyping—a bias that begins in infancy and persists even among the most enlightened employers, ” Sciences-New York 1998, 38 (1), p. 18; and Gerhard Sonnert, “Women in science and engineering: Advances, challenges, and solutions, ” Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1999, 869, p. 34. |

|

28 |

Howard Georgi, “Is there unconscious discrimination against women in science?” APS News, 2000, 9(1), The Back Page, available at <http://www.aps.org/aspnews/0100/010016.html <; and Who Will Do the Science in the Future? (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 2000). |

What They Say Versus What They Do

Again, the crux of the problem appears to be the departmental culture as exemplified by its reward system. Professors are human beings —they are mammals who want to feel good and loved and respected and get fed well and patted on the head, so they respond to the operative reward structure. In my opinion, the reward structure of the university has evolved an organism—the chemistry department of today—that is extremely hostile, unhealthy, and brutal to people who want to do something besides chemistry around the clock.

What does the departmental reward structure say it rewards? The first duty of chemistry faculty is to the young people whom they have chosen to teach, mentor, and guide in the joys and rigors of chemistry. Their second duty is to quality scholarship. In my worldview, if you want to do chemical research and not teach, not mentor, not guide students in the joys and rigors of chemistry, you have no business being in a university. Go do research somewhere else. Students are not cannon fodder.

Whom do chemistry departments really reward? Those faculty who bring in the most overhead-bearing monies, who excel at promoting their science, and who are single-minded and aggressive. Many people—men and women—are not comfortable with these attributes being the most rewarded and respected professional expressions of competence.

A valid point can be made that the U.S. university system does in fact serve society very well, in many ways, and produces people who do great science. So what! Does this mean that the university won 't serve society and science better when it changes and integrally includes women and minorities? Science will look and be different when we bring in people with different perspectives, abilities, and even different analogies through which to think about their science. As scientists, we are always thinking in analogy, but if we always dip into the same pool, we limit the richness of our analogies.29 And, should U.S. taxpayers have to support a discriminatory institution? I think these are all fair questions.

REDEFINE WHAT DEPARTMENTS WANT

How can matters improve when 10 percent or less of the applications for faculty openings in chemistry come from women, although the candidate pool is at 33 percent? One way is to stop accepting the male dictionary as the operative lexicon. Women and men must challenge the standard terms and patterns and expectations. For example, most university faculty search committees are not really search committees; they are manila-envelope-opening committees. These committees do not seek out new life forms (i.e., women and minorities). If a life form sends in a manila envelope, the committee will open it, but the members of the committee are not going out there to search for new life forms. Universities understand that to build competitive functional teams, recruitment is absolutely vital—they would fire their basketball coach if he didn't do it. Chemistry departments also have to recruit what they need, and they need women. Chemistry departments already recruit the men they want as faculty.

Now the members of the manila-envelope-opening committees are the same people who have been generating the 20 percent—and higher—fraction of women Ph.D.s since 1985. Why have these faculty not wondered why more of their women doctorates were not applying to academia? That discrepancy should have made the faculty on the manila-envelope-opening committees wonder what that said about their department as a place to create a career. What does that lack of curiosity say about their ability as

|

29 |

Londa Schiebinger, Has Feminism Changed Science? (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999). |

scientists to observe and make deductions with respect to a natural phenomenon occurring right under their noses?

So our faculty search committees must recruit women and minorities and not just open envelopes. But if search committees really become search committees, one of the things they then need to recognize is that there is always bias in evaluating applicants' packages. Recruiting novel life forms is not going to help if they are evaluated in a way that makes it irrelevant that they applied.

GUARDING AGAINST THE MYTH OF OBJECTIVITY

Men need to get over this fantasy they have that they are objective. They aren't. As psychologists have shown,30 women are not objective either, but more of us do seem to be aware that we are not objective, and we step back and admit, Maybe I had better give this (situation, person, application) another look. That recognition is an important step. We now have to start training men to recognize that they are not objective and that they, too, need to step back and look at the situation in slightly different ways. As Georgi points out, expand the evaluation criteria. Do not use the standard-operating-procedure list of criteria as the only way to rank candidates.31

Men also need to recognize a chemical truism: like dissolves like. Like likes like. Like does not like unlike. When something in an applicant's package reminds a committee member of himself, he immediately becomes a champion for that package—and most men are not going to see something in a woman's application package that reminds them of themselves. Let us look at some examples where women are deemed “unlike” and less qualified for the job.

This first example, reported in the Washington Post in 1997,32 described the enormous increase in women appointed to orchestras once orchestras started holding auditions behind screens. Because the people evaluating the performances had no idea if a man or a woman was playing.

The second example comes from psychology, a field that is very aware that a gender schema exists and that men are overvalued and women are undervalued. Even psychologists are seriously hurt by gender schemas: a study showed that university psychology professors prefer two-to-one to hire Brian Miller over Karen Miller, even when the application packages under review are identical. Merely attaching a male name to the curriculum vitae raises the apparent quality of that application in the eyes of both male and female reviewers. 33

In the third example, a study of fellowships awarded by the Swedish Medical Research Council showed that the productivity of a woman candidate applying for the prestigious SMRC fellowship had to be 2.5 times more stellar to get the same competency score as the average male candidate.34

It is clear that serious bias exists in how women are perceived in terms of their productivity and competence: women are consistently undervalued for their qualities and accomplishments. Search committees, department heads, deans, provosts, and university presidents need to be aware of this

|

30 |

Virginia Valian, Why So Slow? The Advancement of Women (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998). |

|

31 |

Howard Georgi, “Is there unconscious discrimination against women in science?” APS News, 2000, 9(1), The Back Page, <http://www.aps.org/aspnews/0100/010016.html>; and Who Will Do the Science in the Future? (Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 2000). |

|

32 |

“Do unseen musicians get fairer hearings?” Washington Post, 13 July 1997, based on a report by Cecilia Rouse and Claudia Goldin to the National Bureau of Economic Research. |

|

33 |

Rhea E. Steinpreis, K.A. Anders, and D. Ritzke, “The effect of perceptions of gender in the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: A national empirical study,” Sex Roles: J. Res. 1999, 41, p. 409 (reported in the Washington Post, 2 April 2000). |

|

34 |

Christine Wennerås and Agnes Wold, “Nepotism and sexism in peer review,” Nature 1997, 387, p. 341. |

cultural, unconscious bias and devise mechanisms to evaluate candidates (and faculty) and their productivity more fairly.

Search committees certainly know how to be proactive because they are when they recruit men: they check in with their colleagues and ask, Who is in your group, who's going to be the star? They must ask this of groups that graduate excellent women candidates. If only those professional colleagues are contacted who graduate excellent male Ph.D.s but very few women Ph.D.s, the search committee is not doing its job.

WIN THE BATTLE, LOSE THE WAR?

If search committees are converted into search committees, will that be wasted effort? If the problems enumerated above with respect to the unhealthy environment in chemistry departments are not solved, women will still vote with their feet and not apply to a university. To highlight the difficulty posed by the current environment of chemistry departments, I will now anonymously quote some of my electronic correspondents.

This first message was sent by a male professor with 19 years' experience: “A recent graduate student, the student who gave the best preliminary exam I have ever sat on—she should have been quizzing the faculty, absolutely fabulous—is headed for industry despite intense urging by me and her adviser and several others, proactively lobbying for this woman to go into academics. She doesn't need this mess. You cannot hire someone who doesn't apply.” This stellar young scientist is not applying because she has treaded the water and she does not want to be in that particular pool.

Here is a discouraging observation from another male correspondent: “I do not sense that our best female graduate students are necessarily interested in academic careers. The strong economy and relatively low academic salaries may be partly to blame for this, but I think there is more.” He hasn't quite yet acknowledged that the departmental environment is the “more.”

I received the following message from a young woman who recently graduated from one of the premier groups at one of the premier California universities, who has just taken an academic job and chosen to dive into the pool. “This fall I conducted a job search for academic positions in chemistry. Many of the departments that had the lowest percentages of women were those that did not interview any, although there were certainly highly qualified candidates applying. I had a number of female colleagues with impressive academic achievements who applied this year. I think the departments that are most deficient in women are the ones most intent on staying that way, a difficult problem to remedy. I completely agree that without outside pressure it is likely that the situation will not change on a satisfactory timescale. ”

A satisfactory timescale is now, as we replace those scientists hired in the 1960s. Once that exchange of new-for-old faculty is complete, the door to academia will again be closed for a (long) while.

Here are some thoughts from another male correspondent: “I am on sabbatical with a small company and I think this is truly the future. This company is at least 50 percent women, and the upper management is also about 50 percent women. There isn't the slightest hint of friction or discrimination. I think this is where a lot of women are going and feeling very comfortable with their situation. It is extremely difficult for me”—and he is actively trying—“to encourage anyone into academics anymore, women or men.”

And, of course, we have President Vest's realization: “I have always believed that contempo-

rary gender discrimination within universities is part reality and part perception. True, but now I understand that reality is by far the greater part of the balance.”35

The environment is the problem, and the environment is populated by men. As a completely different male correspondent said (and, yes, his tongue was in his cheek): “Saw the editorial. I was shocked—shocked—after all these years to find out that men were the problem. I never would have guessed.”

It's not news. The men are the ones who run the system. They are the ones who are rewarded by the system. They are the ones who are going to have to agree to change the system. They will be helped by plenty of women, but they have to be a big piece of the efforts to change the system.

THREE OPTIONS FOR FIXING BROKEN INSTITUTIONS

First option: Complete demolition—start over.

Second option: Coercion—use a hammer or a very big stick. A very big stick would be the withdrawal of federal dollars. If the case can be made that chemistry departments have merited the application of Title IX, that will put universities in serious trouble, no doubt about it. And making a plausible case for Title IX appears possible. If so, where does the fault lie? Not with the women. They have done what was asked of them: stay in the pipeline long enough to get a Ph.D. Pumping more women Ph.D.s into the profession was long thought to be the start to the solution. But increasing the fraction of women with Ph.D.s in chemistry from 20 percent in 1985 to 33 percent in 1999 has not solved the women-in-science problem.

Third option: Change the reward structure—admit, as a profession and a society, that this system is still very vital, but that it must be changed. How does one change a standing structure? Change the reward structure. Do that and people change their behavior. Most mammals are not very adept at doing something just because it is the good, noble, moral thing to do. We do it because we are rewarded.

CARROTS ARE FOR VEGETARIANS

Another correspondent comments: “Title IX. I like the premise. It's just like with kids. If there is no consequence to bad behavior then what impetus is there to change it?” Yes, Title IX is a big stick. A number of other correspondents have offered suggestions that could improve the situation and perhaps avoid the stick. As more than one person wrote to me in the past few months: “I generally prefer carrots to sticks.” My rejoinder: We are dealing with carnivores; carrots are for vegetarians. The strategies that these correspondents propose, if started years ago, should have moved the environment toward one more amenable to women—but if these strategies are implemented right now and given the time they need to work, chemistry departments are in danger of locking in woman-sparse faculties for another generation.

The system is broken, but the system actually went out of its way to break itself. Departmental culture evolved into its current form because of what was rewarded. What the department chose to reward was success at winning overhead-bearing grants, arrogance, and skill at self-promotion. That is what has been rewarded and cherished, and that is what most women want no part of.

|

35 |

“A study on the status of women faculty in science at MIT,” MIT Faculty Newsletter, March 1999, 11(4), available at <http://web.mit.edu/fnl/women/women.html>. |

WHAT WOULD HELP UNIVERSITIES ATTRACT MORE WOMEN FACULTY?

On-site day care, for one thing. University presidents may say that there is not enough space or enough money to make on-site day care happen for the numbers of male and female faculty who want it, but if the university gets hit with Title IX, there will be no federal dollars and there will then be no (or a greatly limited) university. The priorities of the administration will suddenly change. Universities have already demonstrated how fast they move when their federal biomedical research funds are held in abeyance due to violations of regulations regarding human subjects.36 The priorities of the administrations must change to solve this problem.

For another, mentor the junior (and senior!) faculty in a way that illuminates career choices and that shows where the pitfalls and minefields are en route to building a respected career.

We could scale back the demands on faculty. Many of my faculty correspondents point out that they do too many things in the current university environment. People have always worked hard in universities, but now they are working insanely hard. The faculty members deemed highly successful by the reward structure have become the equivalent of CEOs—which requires working 80+ hours a week.

We could also bite the bullet and return faculty to their primary function, the reason we have universities in the first place: to train and challenge students and to conduct scholarly research that contributes to the greater store of human knowledge.

Lastly, change the reward structure. I have posited Title IX as a course of action37 because I think punitive measures have been earned and paid for in full, but changing the reward structure also has much to offer as a strategy. Really reward those faculty who are there for the right reasons: for the students and for scholarship. The university that does so will inevitably alter its departmental environment to one that women will choose and one in which men and women will enjoy being citizens.38

People in academics do it right—we all know faculty who do. Let us start rewarding them. And why should we do that? Because a brutal environment—and I would, again, postulate that the typical U.S. chemistry department is a brutal environment—drains the joy out of doing science. Let me give you a personal example. A former postdoctoral associate of mine commented recently that it was a high tribute to my Ph.D. adviser, Royce Murray, that every person she had met who had come through his group—and she has now met about 10—retained a love of science, a desire to get in there and tussle with science and scientific questions. Coming from one of the Ivy League schools, she has seen more than her share of the browbeaten, and they are not joyous scientists. This country should want joyous scientists.

CAN THE FUNDING AGENCIES PLAY A ROLE?

A number of my correspondents have suggested that it is time to start funding graduate students outside the competitive grant-proposal-writing system. Faculty spend much of their time writing too many proposals instead of mentoring students. Others have suggested that if the federal government wants to step in and provide half the start-up package for women, strong but unfairly undervalued candidates will immediately be raised higher in the ranked list.

|

36 |

Sheila Kaplan and Shannon Brownlee, “Duke's hazards-Did medical experiments put patients needlessly at risk? ” U.S. News & World Report, 24 May 1999 (the Web version of the story can be found at <http://www.usnews.com/usnews/issue/990524/nycu/trials.htm>). |

|

37 |

Debra R. Rolison, “A Title IX challenge,” C&EN, 13 March 2000, 78(11), p. 5. |

|

38 |

I predict that if the reward structure is changed, the system will turn on a dime. |

A rather provocative suggestion comes from someone who served as a rotator at NSF in the early 1990s: If a graduate student costs $33,000 a year,39 just fund every chemistry graduate student in this country at $33,000 a year. The faculty can then do their job without fear that the students will starve. If people want more than that, including postdoctoral researchers, then write a proposal. This correspondent also looked at the support of graduate students through NSF-funded proposals (in the early 1990s) and contrasted that with the total number of third- and fourth-year graduate students in the country. The dollar amount spent via NSF grants on students was the same number as would be spent funding every third- and fourth-year chemistry graduate student in the country—and all without writing one proposal. Those two pots of money are the same, but in the current scheme of things faculty have to work nonstop to ensure the funds are kept flowing and the students supported.

What if block-funding of graduate students were made available? Would that allow the funding agencies to focus on reviewing and funding the less safe proposals, the ones exploring nonmainstream problems, the ones so difficult to get through the current funding system? One can also wonder what such an arrangement would mean for student choice and market freedom. A block-funded graduate student would be the “buyer” and the professor the “seller,” so the research program and environment would need to be appealing in order for the student to join the group. Might a marked change in graduate-school dynamics result?

With respect to the many proposals that any active researcher must write these days, the reality is, We have met the enemy, and it is us.40 Researchers are trying to do more than they did 30 or 40 years ago. We tackle multiple problems requiring cross-disciplinary skills (if not teams of people) with multiple people per problem and all the high-tech instrumentation that that implies—ergo, we require multiple funding lines and must satisfy multiple sponsors. Gone (for most of us) are the days of specializing in one system, one technique, and exploring it with a few graduate students for many years. The science is more interesting now, I think, but we have contributed to the systemic breakdown.

CRITICAL MASS

The need to achieve a critical mass of women in chemistry departments is often mentioned as the way to solve the problems women face in academic science. But does critical mass magically solve the problem? Does getting women onto the faculty of science and engineering departments at critical mass—deemed to be about 15 percent—solve the problem? Only partly, according to Etzkowitz and coauthors,41 who wrote, “The fallacy of critical mass as a unilateral change strategy is that female faculty pursue strikingly different strategies. They differentiate themselves because they have different goals.” Women, like men, are not monolithic; we differ. We do things in different ways from one another—and we don't all like each other. And this differentiation among female faculty sometimes produces isolation even when the numbers on an absolute basis have reached the purported critical mass.

Etzkowitz et al. make another important statement in their paper: “Informal networks are indispensable to professional development, career advancement, and scientific progress. Contiguity of helpful colleagues improves the conditions for scientific achievement.” Contiguity is the key. It is not just a

|

39 |

The figure of $33,000 arises from the following estimate: a generic stipend for a graduate student plus tuition plus overhead, costs about $30,000 a year. Add another (burdened) $3,000 so that the student can do research, whether with chemicals or computers or a laser. |

|

40 |

Apologies to Walt Kelly and Pogo. |

|

41 |

Henry Etzkowitz, Carol Kemelgor, Michael Neuschatz, Brian Uzzi, and Joseph Alonzo, “The paradox of critical mass for women in science, ” Science, 1994, 266, 51. |

critical mass that must be achieved, it is a percolation threshold. For example, in a three-dimensional system in which the volume is filled with black balls and white balls, in order to achieve continuity of transport properties among the minority component, you have to reach a percolation threshold (a volume fraction) of either 15 percent or 18 percent.42 Until the percolation threshold is reached, the minority component is isolated from the community of the whole. It is the communication between the minority balls that is critical to impart their character to the whole.

If a nominal critical mass is reached and 15 to 18percent of the faculty in a chemistry department is (finally?!) female but that critical mass does not communicate, it isn't a critical mass, because a percolation threshold has not been achieved. It is the communication that is important. In my opinion, critical mass as a singular goal will not solve the problem women face in science any more than keeping women in the pipeline has solved the problem. We are keeping women in the pipeline: 33 percent of our Ph.D.s in chemistry are now women, which helps—it has to help—but which has not solved the lack of women in academic chemical sciences. My concern is that if reaching a critical mass of women in an academic department is defined as the goal—the only goal—then achieving it may still not solve the problem of fully integrating women into the enterprise of science.

And a final concern: If we cannot pull women chemists into academics when we are graduating one woman for every two men, how are we ever going to get minorities on chemistry faculties?

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank Janet Osteryoung and the Organizing Committee of the Chemical Sciences Roundtable for allowing me to expand on the 650-word editorial, written for the March 13, 2000, issue of Chemical and Engineering News, in which I proposed applying Title IX to U.S. universities for their “entrenched inability to hire women” in their departments of chemistry. I am deeply grateful for (and to) the numerous correspondents—students, postdoctoral associates, governmental and industrial scientists, professors, and nonscientist taxpayers—who sent and continue to send me their observations and suggestions with respect to the absence of women in the academic chemical sciences. Many of their comments have been included in this article. My greatest debt is to George M. Whitesides of Harvard University, for catalyzing my thinking on this topic and for providing a rigorous contrapuntal line: his half of the conversation considerably sharpened the shape and flow of my arguments.

DISCUSSION

Marylee Southard, University of Kansas: I have two questions. First, is there any way that we can get copies of your slides?

Debra Rolison: Yes, if your server will take a 6 MHz file you can get a copy from me.

|

42 |

Richard Zallen, The Physics of Amorphous Materials (New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1998), chap. 4. The percolation model distinguishes between bond percolation, in which a pairwise connection exists between sites with bonds either connected or unconnected (percolation threshold is reached at 18 percent), and site percolation, in which all sites are connected and the sites, rather than the bonds between sites, establish the character of connectivity (percolation threshold is reached at 15 percent). If the analogy holds, and the number of connected bonds is the critical component for women in an academic department, then the “critical mass” threshold is reached at 18 percent. |

Marylee Southard: Thank you. My second question concerns a system that is more completely broken, I believe, than what you had time to talk about today. This example is not in a chemistry department or a chemical engineering department but in a biology department that I know about. Six people were up for tenure. Two of them made it; the other four were two couples who didn't make tenure primarily because they didn't get a federally funded grant during their first 5 years. One of them was up for the highest teaching award conferred by the student body. Do you have any comments about this?

Debra Rolison: I think we often try to reassure ourselves that things are better for women in biology because the numbers are so much bigger. But two days after my editorial came out I heard from a plant physiologist: “Please come talk to us because we have the same problem.” Clearly, critical mass has not solved the problem, and I agree it is broader than just chemistry and chemical engineering departments. I think we have to retrain universities as a whole to understand what their function is.

Linda McGown, Duke University: I loved your talk—you raised a lot of really good points. I would like to address one of these, the myth of the 150-hour work week, which I think is one of the things that keeps people from trying to participate in academics. In my own group I try to encourage my students to integrate their lives with their graduate studies. I think it is the best preparation you can give them for life after graduate school regardless of what area they go into. If they want to get married, I don't feel that they should have to ask my permission in the first place, but I go further and give them my blessing. If they (or their wives) have children, that is okay. I don't feel that I should have input in those sorts of decisions as long as they do their job.

Then the question is, What is their job? Is it face time or is it getting the work done? I have never seen that there is a significant difference between really good people who work for 40 hours and other people who are around for 90 hours. I just don't think that you can sustain that level of intellectual activity. I am lucky if I have 2 hours of serious original creative thought a week. The true gems do not occur often. You cannot force them. The rest of it is fluff, and I can do that fluff at home, at work, or in the car.

There are other kinds of things that you have to do, granted, although I don't think that is science, and I don't think that 90 hours makes a better scientist, although people have that perception. They believe that there is a linear track for certain times of your life. It is the medical school model as well, where you put off doing something—such as getting married—until you get your Ph.D. Then you put off kids until you are in your forties or fifties, and that doesn 't work either. I had both of my children while I was in my tenure-track years. You could look at my productivity and the productivity of my colleagues, male or female, and I really don't think you could tell from the statistics if—or when—I (or they) had children.

I don't think there is a significant difference between my colleagues and myself. I think it's more an attitude of hazing in some respects and a culture that tries to make it as difficult as possible for people to do anything else—particularly if it involves time.

This is academia. We have the most flexibility of any job, and yet here we are saying that it's easier in industry to have children. I do not understand this. When my children were born, I was at home, and I had group meetings at home—we have computers now, and we have all kinds of means of communication—so I was gone for just a month or two. Now, I have never taken a sabbatical—which is my personal choice—but I have colleagues who were on sabbatical, and I could not tell because I hadn't seen them in 2 or 3 years anyway. These are all side tracks off the main issue of integrating your life into your career. It is so terribly discouraging that for some reason academia is not perceived as a wonderful

place where you can think and ponder—do wonderful science and have a life. Instead it has been turned into a dungeon-like atmosphere.

Debra Rolison: Hamster on a wheel!

Linda McGown: It is really terrible, but I do think a lot of the problem is perception, because it hasn't been that way for me. I am not always happy, but I still choose to remain in academia. I have never opted out because deep down I love it, and I hope that I am an example to my students and to other people that you don't have to do things according to some schedule that other people give you. Just take the flak and tell your students to take the flak because academia is worth it. Others have no business telling you what to do with your time, if you are pulling your load.

Mary L. Mandich, Bell Labs: I really enjoyed your talk, and I think your proposal for withholding the funding would get right to the heart of this problem. At a recent lunch of professors in physics and chemistry, more than one professor suggested that distance learning is threatening higher education, especially really good higher education. I asked them why they thought that. They said, “Well, you know the quality of the teaching is really going to go down.” And I said, “With all due respect to you folks in academia in this room, I've had some really lousy teaching at universities, and I've had some very good teaching. I would think you would get the same thing over the Internet—some really good course material and some really lousy course material.” They said, “No, no, no, it's going to be really lousy.” “Well,” I said, “I have actually seen some really good stuff, so what we need is some way to sort through and find the really good stuff. Maybe the ACS and the APS could promote the good Web sites and help people find good material.” To which a very distinguished professor said, “It would ruin universities because we would no longer have students to teach in chemistry and physics. They would go on the Internet, and our departments would shrink, and we would not get federal grants, the overhead of which is absolutely vital to the university.” This is why I think going after funding goes right to the heart of where the university will be hurt and will have to change in order to survive.

Patricia L. Watson, DuPont: I have a comment about effecting change that comes from our experience at DuPont in the late 1980s and the early 1990s, when we were concerned about many issues in the workplace. Now, there are lots of professional issues, but as far as work and family issues were concerned, people at DuPont were working very hard. All the stresses that are seen in academia are certainly there in industry as well. We had a person, Faith Wool, in our human resources office who was an extremely innovative and assertive woman—in fact she was recruited by the Clinton Administration to help frame the Family and Medical Leave Act. Faith took the initiative to do several surveys at DuPont—very large and inclusive surveys—and after the second or third survey in which she had gathered a lot of information about retention and satisfaction, a lot of things started to happen around family and work issues.

What actually got people's attention—after they had absorbed the percentage of women that had considered leaving DuPont because of these issues—was the number of men who had considered leaving DuPont. It was at least half as large as the number of women. Until that point women were considered more of an issue because more of them had taken action to go to small companies and so on, as we have heard. But what I think precipitated changes at DuPont was when men in upper management noticed the number of men leaving. And I don't believe that at universities all the men are satisfied with the situation either.

Debra Rolison: Yes, we are hearing more about how unhappy they are with the situation.

Patricia Watson: Right. So getting some data on that could be very useful.

Debra Rolison: I would also comment that this is what made Ruth Bader Ginsburg's career: She sued to get family privileges for men. Women were having no luck in the courts, but she started to make the same points for men, and they succeeded. I think Joan Valentine said it best a long time ago: “When departments treat people well, women will do well in those departments.”

Elizabeth Theil: I would like to comment on the stick approach as opposed to the carrot that was the NIH response on the issue of salary equity in the 1970s. I know, because I was a beneficiary under the Carter Administration, which encouraged salary equity. The NIH did surveys of PIs by gender at different institutions. They then wrote to the provosts of those institutions where the women were way out of line in terms of salary and threatened to withhold future NIH funding. That certainly got the attention of the provosts, and so the two women at my institution (North Carolina State University, where I was a faculty member for many years) who had NIH grants as PIs got salary increases for 2 years in a row. But the deans never bought into it, and as soon as the NIH went away, the salaries receded. So, it does work, but it has to be built in a way that provides continuity. I think the only way to do that is to have a money component that is also related to the requirement for critical mass. If you get a large enough number of women or men with the right ideas into a department with this threat, then when they are in place they will be able to make sure it continues. But if you just have isolated cases it won't work.

Debra Rolison: You almost need the entire chain involved. We all know departments that are really trying to bring women in—but the women aren't applying because they perceive academia as a career they don't want. And yet the departments don't necessarily have the money to do what needs to be done. The dean, the provost, and even the president have to be willing to redirect money because gender parity has now become a priority. We all know how fast universities implement the missing human studies requirements once the government yanks biomedical funding: one week later they are up to code. So it does get the attention at the right level, and then they have to be able to put pressure all the way down. I am surprised the provost didn't start yanking some of the dean's slush fund. That's what I would have done.

Robert L. Lichter, Dreyfus Foundation: I wanted to make a couple of comments that don't at all take away from the premise of the discussion but may help put some things into historical perspective. First, I would argue that the origin of the problem is not the grants themselves or the concept of grants but the structure of universities, because that structure long preceded the post-World War II grants-based mechanism for research support. For example, the argument doesn't apply in disciplines and departments in which grants play a much less dominant role, such as in humanities departments. I was a vice provost for research and graduate studies at a doctoral institution where you could find the same kinds of circumstances for women but where grants weren't the source. However, the grant-based mechanism can indeed exacerbate the barriers to the advancement of women.

My second point is really a side issue. A recent article in Science about Italian universities (including Bologna) pointed out that in the 19th century they were actually very welcoming toward women.

Debra Rolison: They were. Germany and other European countries are discussed in Noble's book.43

Robert Lichter: Portugal actually was hostile.

Debra Rolison: I think Portugal still is. I know a number of women scientists from Portugal.

Catherine Woytowicz, American Chemical Society: For the few of you who stopped me in the hallway and thought that I was complaining about the ACS, I want to say that that is absolutely, 100 percent, totally wrong. The ACS is the best place I have ever worked; I think it is a fantastic environment, a fantastic resource. I cannot say enough about it. If you are not involved, you should be. Really, I cannot say enough about it. It is what brought me here to Washington.

A second point is that while you made me feel really bad that I am an academic dropout—I quit academia to take this job—I guess I may now feel browbeaten into going back.

The third thing that I want to say is about women who are trying to make a case for their own advancement. Men are traditionally far better than women at self-promotion, and we haven't been doing a lot of that. So when you are doing your networking with those five pink pages, be sure to speak up when you have something worth crowing about. And if no one else says that you have done a good job, be sure that you say you've done a good job. Because it takes a few people saying, “Oh, yes, she did a good job,” and if they hear it enough they will start saying it, too. That is one way that a little bit of promotion goes quite a long way.

One last thing, kind of a horror story. One of the reasons I nearly didn't go into academia was a professor—you probably know who she is, and if I said the school you would know exactly who she is—who was between departments. She had a joint appointment, which meant she was neither a bird nor a bee. She got pregnant, and with the stress of trying to make tenure in both of the departments and trying to be all these different things, she suffered two miscarriages in 2 years, while her students were working 70-hour weeks. She was put on bed rest. The whole world was going kaplooey and all of us came to the same conclusion: Why do we want to do this?

There is a lot to be said for an environment that is good for women and much to be discussed about an environment that is bad for women. If you don't have the right kinds of policies in place, go back home and see what you can do about them.

Debra Rolison: I very much agree about the self-promotion. As women we are socialized not to brag, to be modest. You don't necessarily have to do it the way the men do, but you can at least tell your colleagues what your latest neat result was. Just focus on the science. I recommend Liz Sobritsky's article in Analytical Chemistry on 1 April.44 She interviewed 28 women analytical chemists, and there were a lot of these very same points brought up. The point is that you really can tell people about yourself and just focus on the science, because your colleagues aren't necessarily paying attention to what you are doing. They are busy, so you have to tell them what you are doing, and it doesn't have to look like hype or bragging.

|

43 |

David F. Noble, A World Without Women—The Christian Clerical Culture of Western Science (New York: Knopf, 1992). |

|

44 |

Liz Sobritsky, Analytical Chemistry, 1 April 2000. |

Marion C. Thurnauer, Argonne National Laboratory: Your comments reminded me of two studies carried out in the mid-1980s, one at MIT45 and the other at Stanford.46 These studies examined graduate student life and surveyed both male and female graduate students, asking questions about their situations as graduate students. I believe the conclusions were that male and female students had similar (rather negative) assessments of the situation. Women, however, were willing to discuss the situation and act on it—by dropping out. It was disheartening to see similar articles a year or two ago, because they appeared after a student had committed suicide. I think you have offered some solutions to this somewhat negative situation. For me, this is the difference between now and 15 years ago.

Debra Rolison: I like to be provocative.

|

45 |

M.S. Dresselhaus, IEEE Trans. Educ. E-28, 196 (1985). |

|

46 |

L.T. Zappert and K. Stansbury. “In the pipeline: A comparative analysis of men and women in graduate programs in science, engineering, and medicine at Stanford University. ” Tech. Rep. Working Paper 20, Institute for Research on Women and Gender, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, 14 November 1984, p. 11. |