9

Scientific Research, Information Flows, and the Impact of Database Protection on Developing Countries

Clemente Forero-Pineda1

Universidad de los Andes, Universidad del Rosario, Colombia

INTRODUCTION

This paper addresses the potential economic and scientific effects on developing countries of database protection and of the general trend toward restricting the public domain of scientific information. The analysis takes into consideration the specificities of scientific practices in developing countries and the institutional framework. Scientific knowledge and databases are produced differently in developing and developed countries. Some issues relating to differential access to scientific information are discussed. The economic and scientific impacts of granting further intellectual property protection to databases not covered by copyright agreements under the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement are analyzed from this perspective.

The following questions guide this line of thought:

-

What is the role of information flows in science?

-

How is scientific knowledge produced in developing countries?

-

Is there any difference in the way scientists from developing countries use information compared with the use of information by their peers in developed countries?

-

How are databases produced in developing countries and for what kinds of markets?

Should developing-country scientists expect effects of sui generis protection of databases different from those envisaged for science in the developed countries?

-

What is the relevance of certain specific institutional arrangements, such as the public domain, “fair use,” and differential or discriminatory pricing?

-

Are compensatory direct subsidies to developing countries viable?

-

What are the consequences of database protection and a narrower public domain of scientific information for international scientific collaboration?

Recent studies on the research process point out new roles of information flows and cooperation in the production of scientific knowledge. Although well recognized by writers on the social and institutional conditions

of scientific communities, the role of the public domain in information is now being emphasized in the study of knowledge formation as a social, collective process.

An interesting approach to understanding the benefits of collaboration and fluid exchange of information is the evolutionary stance of Loasby (1999), who views a knowledge-rich society as “an ecology of specialists” that may grow provided it is “sufficiently coordinated to support increasing interdependencies” (p. 130). Nonaka and Konno (1998), in their attempt to explain the foundations of Nonaka’s model of the conversion of tacit into explicit knowledge and vice versa, relate knowledge with the notion of ba, the Japanese word for a shared space for emerging relationships, and where knowledge conversions can unfold. Stacy (2001) has advanced the view that “knowledge is not a ‘thing’ or a system, but an ephemeral, active process of relating.” Exchange and collaboration are central to this new epistemology, where flows of information are perhaps more valuable than stocks of information.

These three views converge into stressing the importance of a public domain in science and knowledge processes in general. They point precisely at the critical role of information flows for scientific activity in developing countries. Communication and collaboration are at the heart of these countries’ aspiration to science, and access to scientific information is critical to their work.

INFORMATION AND THE PRODUCTION OF SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE IN DEVELOPED AND DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

From an economic and social perspective the practice of science in developing countries is paradoxically akin to scientific research being performed in emergent areas of knowledge in developed countries. The replication of many simple experiments in developing countries usually requires creating a specialized and costly laboratory. Entering the circuits of world scientific activity or building networks of interested peers is accordingly difficult. Environmental, sociometric, and econometric research often demand initiating the collection of ad hoc statistical series. Scientists in these countries cannot easily reap the economic advantages of nonrivalry, in contrast with the belief of many economists who take for granted the nonrivalry of information, knowledge, and scientific networking. In this respect, science in developing countries is akin to frontier research carried out in developed countries, even when the purpose is obtaining a marginal result.

Based on detailed empirical studies by H. Collins (1985) and others, Michel Callon (1999) makes a distinction between two categories (or dynamic states) of science: emergent and consolidated science. In emergent science (science being done in emergent fields of knowledge) the diffusion of knowledge is not without cost. The transfer of knowledge (through replication for instance) demands heavy investments on the part of peers. Measurement instruments, seminars, and sometimes the building of new laboratories are necessary for knowledge to be appropriated. In contrast when scientific activity in one field is in a state of consolidated science (a concept akin to Kuhn’s normal science), the traditional assumption of cost-free transfer of knowledge is acceptable. In the dynamic perspective proposed by Callon one scientific field may alternate between phases of emergent and consolidated science.

In certain aspects science in developing countries resembles emergent science. The replication of all experiments demands heavy investments. Transfers of knowledge from international peers require important local capital investments in scientific equipment, just as in the projects of their emergent science peers of developed countries. The percentage of equipment in project budgets is high. The process of networking and gaining the interest of their peers2 is very demanding.

In other respects there are similarities between consolidated science in developed countries and science in general in developing countries. Expected results of projects are in general normal science propositions, developed within dominant paradigms or confronting marginal aspects of these paradigms. In both cases the reliance upon information resources is critical.

There are great differences as well between the normal practice of science in developing countries and both emergent and consolidated science in the developed world. Even the replication of simple experiments demands high investments because of the sparseness of scientific infrastructure, usually built in response to the demands of a few previous projects of each laboratory. The structure of expenditures in research projects shows that simple research projects in developing countries grant a share to library and digital resources, documentation, travel, and communication activities in a proportion that is considerably higher than that observed in emergent science projects of the developed world (CTS-Columbia Project, 2003). At the same time, access to financial resources is scarce.

Independent from the institution-building efforts by universities, public libraries, and special documentation projects in developing countries, it is common that a single research project will have to build information resources practically from scratch. For example, journal collections frequently are incomplete and subscriptions are restored only when individual projects demand it. This is the case when a research group or laboratory is built to nest a returning, recently graduated young researcher or when a team of experienced scientists joins to open a new avenue of interdisciplinary research. It is also true for new projects of well-established research teams. As a consequence, though reliance on information is equally critical for scientific activity in both developed and developing countries, a higher share of resources must be allocated in the latter to information resources to compensate for the sparseness of library and documentation resources.

The benefits to global science of incorporating researchers from developing countries have been analyzed elsewhere (Forero-Pineda and Jaramillo, 2002). Under a wide range of circumstances scientists from developed countries have shown interest in the research being done by researchers from developing countries. Both academic interest and altruism of scientists in the more developed world have played a role in meeting part of the information requirements of research projects in developing countries. In the basic sciences research projects in developing countries almost invariably refer to international links with laboratories and researchers in other countries. Scientific collaboration is the rule for leading research groups and fair use of copyrighted information is an important mechanism facilitating the access of researchers from developing countries to scientific information not directly available to them (CTS-Columbia Project, 2003). Some developing and transition countries have at times created networks of expatriate scientists that have played a key role in mobilizing scientific altruism (Forero-Pineda, 1997).

Besides the general argument showing how critical access to information resources is for scientific endeavors in developing countries, there are reasons to believe that scientists in developing countries may find comparative advantage in information-intensive research, provided access to information is maintained or enhanced. Consider the high cost of scientific equipment and reduced budgets for science in countries of lower income. Under these circumstances scientists in these countries would normally tend toward methodologies that rely specifically on open access to information. The types of research that depend more on the availability of and open access to information than on investments in scientific equipment are theoretical research in all disciplines; evidence-based research, both in medicine and in social practice; environmental, climatic, econometric, and genetic research based on internationally available data; and case-based or best-practices research in management or in technology applications. These types of research offer advantages to developing-country scientists. As the cost of buying and maintaining equipment is higher than that of maintaining well-informed scientists, and developed countries face less cost constraints, developing countries may have comparative advantages to develop these information-intensive types of research; even if their resources are scarce, the cost of supplying them with information resources is lower than buying and maintaining equipment.

OBSTACLES TO ACCESS

The scarcity of information resources and sometimes of the knowledge necessary to use them still affects the conditions of science in some developing countries. In others this situation has improved considerably as a result of three factors: considerable networking efforts by their scientists, altruism of their peers in the developed world, and the existence of rules (such as the exception of fair use in copyright) allowing and sustaining this cooperation. These rules allow information and other resources to be readily available throughout scientists’ personal networks, and mitigate the handicap of developing-country scientists. They also allow a more important contribution of the

latter to the objectives of the common research programs of those networks. Considerable efforts have been displayed by some developing countries to strengthen these networks, sometimes supported and mobilized by metanetworks of expatriate scientists (Forero-Pineda, 1997). Nonetheless, legal and economic obstacles to information flows remain. The trend toward stronger protection of intellectual property rights over information that is deemed necessary for the production of knowledge, combined with the concentration of databases in developed countries, poses serious obstacles to scientific information flows for researchers in developing countries.

Concentration of Database Production

The production of databases is highly concentrated in North America and Western Europe; 94.1 percent of 12,111 databases traded worldwide and listed in the Gale Directory of Databases are produced in these areas (Williams, 2002, as cited by Braunstein, 2002). These figures do not cover all existing databases, only those that are commercially traded. In the case of databases from South America, for instance, the Gale Directory lists 21 databases, in contrast with 694 reported by Pereira et al. (1999) for Brazil in 1996. Many of the latter are governmental, legislative, and bibliographical databases and are not offered in international trade. As illustrated by this inventory for Brazil most databases produced in developing countries are of local interest. Many of them are not digitized, and most are provided at no charge. In the case of India a similar underestimation on the part of the Gale Directory seems to have occurred. It lists 413 databases for the whole Asian continent, including Japan, while Vandrevala (2002) mentions between 400 and 500 scientific databases in India alone. While the Gale Directory aggregates are perhaps an indicator of the concentration of internationally traded databases and reflect international payments flowing from South to North, they appear to ignore a large majority of databases in both developed and developing countries.

Network Access

There are network limitations for developing countries to access the production of databases that come from the absence of network economies in these countries. Internet networks in these countries are thin and small. Their cost has to be shared among fewer users, making them more expensive.

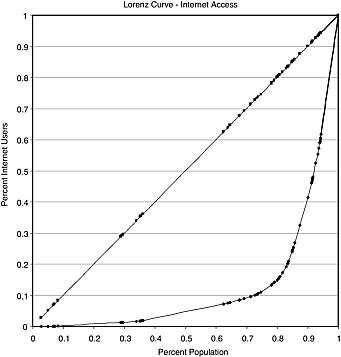

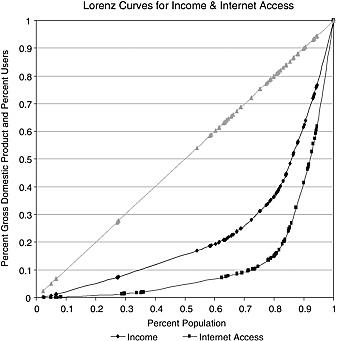

A Lorenz curve may be built, based on Kirkman and Sachs (2001) data on network readiness and United Nations statistics of world population, showing the concentration of Internet access (see Figure 9.1). Eighty-five percent of Internet users are in countries with only 20 percent of the world population. Figure 9.2 shows the size of the problem and the disparity of conditions in terms of income and Internet access. While income was not well distributed in the world in 2001, it was better distributed than Internet access.

The average size of telephone networks in the 75 developing countries studied by Kirkman and Sachs (2001) is 8 million telephone lines. In Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries it is 20 million lines. The average size of the Internet network is 1.5 million telephone lines in developing countries compared with 12 million telephone lines in OECD countries.

There are important economic consequences of this statistical analysis. Developing countries have less opportunity to take advantage of network economies and therefore less potential for database development. Though database markets appear to be global, database development is linked to data production, and both are concentrated.

THE LEGAL PROTECTION OF DATABASES AND SCIENTIFIC ACTIVITIES IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

Original and Nonoriginal Databases

Among the varied information resources useful in scientific research that may be included in the wider definitions of databases, digital databases are extremely important for international scientific collaboration, since the Internet enables the immediate transfer of pieces of information. The debate on providing additional statutory protection for databases has centered on sui generis protection of nonoriginal databases, since original databases

FIGURE 9.1 Worldwide Internet access.

are already protected through copyright, with special exemptions including fair use for academic purposes. That focus, however, should not preclude consideration of the importance of databases in scientific activities of developing countries. The arguments presented previously apply to both.

The border between these two categories is not always sharp, as many authors recognize but often dismiss in their theoretical thinking. Database developers frequently integrate their own information with information available in the public domain. If additional protection is granted to databases already protected by copyright, the exceptions for fair use and the de facto perpetual protection that is granted to databases in certain regimes, equally affect the supply of information for research activities in developing countries.

An issue of special concern in developing countries is that of legal protection of nonoriginal databases. While the TRIPS agreement allows protection of original databases, the protection of nonoriginal databases is granted in the European Union, some northern European countries, Mexico, and South Korea. A significant concern is that even information that is in the public domain simply could be reorganized or versioned and included in proprietary databases.

Preliminary analyses made for Latin American countries show that local production of nonoriginal databases does not seem to be affected by the absence of legal protection (López, 2002), and that most nonoriginal databases are produced elsewhere. This could explain the reluctance of most of these countries to support additional legal protection of databases in the WIPO discussions of 1996.

FIGURE 9.2 Income and Internet access.

Information as a Public Good and Information in the Public Domain

The border between private and public-domain information is not well defined. From an economic point of view a distinction should be made between information as a public good and information being in the public domain. Information may be viewed as a public good when nonrivalry applies to its use and it is difficult to exclude others from its use. This is a category that covers most information. As a corollary a piece or set of information may be viewed as a global public good when nonrivalry and nonexcludability apply to it on a global scale.

In contrast, the public domain may be analyzed in an institutional setting or arrangement. Information is not in the public domain by its public good nature or even by its governmental origin but as the result of a network of formal and informal social agreements, explicit or implicit but entrenched in common law and in the culture of a society. There is a tradition ascribing most information obtained in government-funded science to the public domain, with the important exception of classified research for purposes of national security or economic competitive strategy. Nonetheless, the public domain for information generally is wider than that. It includes information that has lapsed protection, information produced by intergovernmental agencies, or information “contractually designated as unprotected,” just as a legal definition may state. From an economic perspective an undefined area still remains. In the case of information produced by a private firm, data might be gathered by an explicit, intentional, and marginally costly effort on the part of the firm; alternatively, data collection may be “incidental”

to a public activity. For instance, it could be related to a government-granted concession for providing a public service or in general be a virtually costless by-product of other public activities. Should exclusive exploitation rights be granted to the firm over this information? Or, extending the principle and tradition of ascribing government-agency produced information, should it be considered as part of the public domain? The implications of defining these borders as well as those of the definition of databases protected under sui generis legislation are important (Maurer et al., 2001).

Pricing Methods, Transaction Costs, and Access

The market for industrialized countries’ databases in developing countries has very specific characteristics. As in all network products there is an incentive to use introductory pricing or discriminatory pricing.

Differential pricing is a common practice in the database market. Databases may have a posted price of U.S. $50,000 and sell for U.S. $20,000 to a consortium of universities in one developing country and for U.S. $6,000 in a smaller country as an introductory price. As predicted by both the theory of discriminating monopolies and the theory of networks, the pricing rule applied by intermediaries appears to be directly related to the income of countries and to the expected volume of use of the database.

Database trading in developing countries is also subject to high transaction costs. Besides the price charged by database owners there is a dense network of intermediaries operating in developing countries. In the Andean region of South America there are at least five permanently based intermediaries, who operate through representatives. One more intermediary acts in this region through a subsidiary in Brazil.

The strategy used by universities in developing countries to deal with the problem of the cost of these databases has been relatively successful. These universities have created consortia to negotiate access to databases. The perception of academic consortia of database users is that negotiations with intermediaries are considerably harder than dealing directly with database owners.

On the supply side it should be observed that incentives for the production of new database firms increased sharply for one to two years after the European database directive according to Maurer, Hugenholtz, and Onsrud (2001). However, in developing countries, as López (2002) states, “…we have not observed that infant DB industry in the region (apparently concentrated in the most advanced countries) is being affected by the absence of sui generis legislation. Commercial losses seem instead to derive from an inadequate enforcement.”

There is concern that if protection were extended and public agency databases were transferred to private dealers, price increases in developing countries could be substantial. According to López existing protection schemes in these countries are being effectively used, as observed in court cases, and the problem for the development of this industry is more one of enforcement and costs of legal processes than one of insufficient protection.

Closely linked to the issue of prices is that of exclusive use. If there is complete freedom for pricing, the level of the price might be so high as to preserve an exclusive or almost exclusive use, discriminating through the buyers’ ability to pay. Access is clearly affected by these monopoly practices, whether illegal or compliant with the law. Misuse of exclusive rights could be confronted by antitrust litigation, but such legislation is uneven in developing countries and transaction costs of suing in developing countries are very high. The risk of being condemned through litigation is therefore low and it would hardly dissuade monopoly practices in developing countries.3

The economic and scientific consequences of the legal protection of databases on the scientific and technological activities of developing countries should be analyzed in this perspective. Additional legal protection might stimulate new information businesses, in both developed and developing countries. Nonetheless, a simple market analysis would predict that greater legal protection will make access to protected databases more expensive on the average. The incentives for the production of open-access scientific information will accordingly diminish. If, as

shown by Kirkman et al. (2002), access to scientific information is today more expensive for residents of developing countries, these shifts tend to further reduce the possibility of access by scientists in university and government research institutions in developing countries, especially those where university and public library budgets have shown a sharp reduction in the past decade.

CONCLUSION

The arguments presented here are based on a stylized analytical description of how science is produced in developing countries. Results are similar to those of authors who have analyzed the impact of database protection in an institutional context. They differ, however, from those of other authors who present the classical arguments in favor of a strong protection without taking into account the specific ways of producing science in developing countries.

If one adopts the view that institutions and the production of science matter, then the fair use exception of copyright over original material as well as nonoriginal databases; the disclosure provision of patent law; and effective limits to the time span of property rights appear to be fundamental to the advancement of science in developing countries.

If the observed trend toward stronger legal protection of databases were to advance, the end result might not be the end of scientific collaboration, as some have claimed. A new topology of scientific research networks would probably emerge, however. Rather than a global commons for scientific information, a collection of closed and relatively isolated networks would dominate scientific activities worldwide. In this scenario the role of researchers from developing countries in global science would diminish even further in relative terms, as a consequence of the narrower availability of scientific information.

REFERENCES

Braunstein, Y. 2002. “Economic Impacts of Database Production in Developing Countries,” WIPO, November.

Callon, M. 1999. “Réseau et Coordination,” Economica, Paris.

Collins, H. 1985. Changing Order, Replication and Induction in Scientific Practice, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

CTS-Colombia Project. 2003. “The impact of science and technology on Colombian Society,” Universidad de los Andes, Universidad del Rosario, OCYT, Colciencias, Progress Report, September 20, Bogotá.

Forero-Pineda, C. 1997. “Convergence of research processes, big and small scientific communities,” Proceedings of the Global Science System in Transition , Austria, May.

Forero-Pineda, C., and H. Jaramillo-S. 2002. “The access of researchers from developing countries to international science and technology” (coauthor), International Social Science Journal, Special Issue on the Economics of Knowledge, No. 171, February.

Kirkman, G. S., P. Cornelius, J. Sachs, and K. Schwab, eds. 2002. The Global Information Technology Report 2001-2002: Readiness for the Networked World, Oxford University Press, New York, April.

Kuhn, Thomas. 1962. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Loasby, Brian. 1999. Knowledge, Institutions and Evolution in Economics, Routledge, London.

López, A. 2002. “El Impacto de la Protección de las Bases de Datos No Originales sobre los Países de América Latina y el Caribe,” World Intellectual Property Organization, Geneva, November 4-8.

Maurer, S., P. B. Hugenholtz, and H. J. Onsrud. 2001. “Europe’s Database Experiment,” Science, 294, October.

Nonaka, I., and M. Konno. 1998. “The Concept of Ba: Building a Foundation for Knowledge Creation,” California Management Review, 3(40):40-54.

Pereira, M. N. F., C. J. S. Ribeiro, L. Tractenberg, and P. Loureiro Medeiros. 1999. “Bases de Dados na Economia do Conhecimento: A Questão da Qualidade,” Revista Ciência da Informação, Volume 28, No. 2.

Stacy, R. 2001. Complex Responsive Processes in Organizations: Learning and Knowledge Creation (Complexity and Emergence in Organizations), Routledge, London.

Vandrevala, P. 2002. “A Study on the Impact of Protection of Unoriginal Databases on Developing Countries: Indian Experience.” National Association of Software and Service Companies (NASSCOM), WIPO, Geneva, November.

Williams, M. E. 2002. The State of Databases Today: 2002, Gale Directory of Databases, Gale Research Inc., Detroit.