3

MQSA Regulations, Inspections, and Enforcement

Mammography Quality Standards Act (MQSA) regulations have been in effect for more than 10 years, so a review at this time is appropriate to identify areas in need of enhancement. In addition to making suggestions for changes and possible additions to enhance the quality of mammography, the Committee examined the current regulations and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) data from inspection reports in an effort to identify components that could potentially be eliminated without a detrimental effect on quality. This was an important consideration because unnecessary regulations and tests add to the cost and workload of facilities, but do not benefit patients.

REGULATIONS OVERVIEW

Congress passed the Mammography Quality Standards Act of 1992 to provide a general framework for ensuring national quality standards in facilities performing screening mammography. The Secretary of Health and Human Services assigned FDA the authority to implement and regulate the Act’s provisions. FDA Final MQSA Regulations became effective in April 1999. A detailed outline of these regulations can be found in Box 3-1.

Briefly, FDA requires that each mammography facility be accredited and certified. Several accreditation and certification bodies exist today. Facilities must apply for accreditation once every 3 years, a process that requires review of both clinical and phantom images. Accrediting bodies are also responsible for reviewing equipment evaluations and quality control tests performed by each facility and reviewing the qualifications of mammography personnel.

All personnel at mammography facilities, including interpreting physicians, radiologic technologists, and medical physicists, must meet initial qualifications, demonstrate continued experience, and complete continuing education programs. To ensure the quality of patient care, FDA requirements also specify that facilities provide a summary of the mammographic assessment in lay terms to each patient in a timely manner.

The states and FDA perform annual inspections to verify personnel and quality control data and to examine compliance with quality standards such as radiation dosage and image processing. Inspectors also ensure that each facility has established a system to record medical outcomes audit data, such that positive mammographic results can be correlated with pathology outcomes. In order to measure and enforce compliance, FDA established a three-tiered violation system, with Level 1 being the most serious. Sanctions, such as directed plans of correction, civil money penalties, and certificate suspensions, can be imposed on delinquent facilities (Mammography Quality Standards Act Regulations, 21 C.F.R. § 900.12 [2003]).

|

BOX 3–1

|

SOURCE: Mammography Quality Standards Act, 42 U.S.C. § 263b (2003). 21 C.F.R. § 900.1 (2003). |

SUGGESTED CHANGES TO FDA REGULATIONS

The Institute of Medicine Committee on Improving Mammography Quality Standards was charged with making recommendations for changes to existing regulatory requirements in order to further improve quality and to reduce unnecessary burdens on mammography facilities. FDA citation data were one source of information used to identify inspection criteria that may be unnecessary to ensure quality mammography (FDA, 2004a). FDA should take responsibility for reviewing the current regulations to delete obsolete language, reduce redundancy, and improve overall clarity. Furthermore, review of regulations should be an ongoing process undertaken by FDA. The following is a summary of the Committee’s views on the current FDA regulations; a complete summary of suggested regulation changes is presented in Table 3–1.

Accreditation

Sections 900.3 and 900.4 of FDA regulations discuss application for approval as an accreditation body and standards for accreditation bodies, respectively. The Committee agreed on several changes to simplify the accreditation process. First, facilities should submit only the results of the medical physicist’s equipment evaluation to the accreditation body, not the full evaluation, during initial application of a new unit for accreditation. (This is the current FDA-approved practice for accrediting bodies; the regulation change would clarify the practice.) Second, facilities should no longer be required to submit surveys and equipment evaluations to their accreditation body annually; instead, they should be submitted every 3 years as consistent with the renewal process. This information is already being reviewed during the annual MQSA inspection, and additional submission to accreditation bodies is unnecessarily redundant.

New Mammography Units

Qualifications for MQSA certification in Subpart B should be expanded to require facilities to undergo accreditation of all new mammography units, including digital equipment. Inspection data collected since 2001 have revealed numerous citations for nonaccredited units (FDA, 2004a). FDA should employ a more strict enforcement policy for facilities lacking accreditation for all units. Additionally, the accreditation process for any newly purchased units should begin prior to use.

Luminance and Illumination

Viewing conditions are critical for accurate interpretation of subtle contrast differences on mammography films (Haus et al., 1993; Wang and Gray, 1998; Waynant et al., 1998, 1999). The 1999 American College of Radiology (ACR) mammography quality control manual suggests standards for viewbox luminance and illumination levels; however, compliance with these recommended standards varies. An estimate from facilities in North Carolina in 2002 suggests approximately 15 percent (40 out of 248 total) of facilities did not meet the recommended ACR viewing standards.1 FDA should require that viewboxes used for interpreting mammograms should produce a

TABLE 3–1 Suggested Changes to MQSA Regulations

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.2(aa) Definitions |

Mammography means radiography of the breast, but, for the purposes of this part, does not include: (1) Radiography of the breast performed during invasive interventions for localization (2) Radiography of the breast performed with an investigational mammography device as part of a scientific study conducted in accordance with FDA’s investigational device exemption regulations in part 812 of this chapter. |

Mammography means radiography of the breast, but, for the purposes of this part, does not include: (1) Radiography of the breast performed during invasive interventions for localization procedures; or (2) Radiography of the breast performed with an investigational mammography device as part of a scientific study conducted in accordance with FDA’s investigational device exemption regulations in part 812 of this chapter. |

(1) Stereotactic breast biopsy procedures utilize X-ray imaging. In the preamble to the final rules, the FDA stated the following: “Since the publication of the proposed regulations on April 3, 1996, significant progress has occurred in the professional community and FDA now believes that there is enough information to begin the development of interventional mammographic regulations. However, that development requires a comprehensive and careful approach that addresses all the factors involved in such procedures. The agency has already begun the development process by bringing this issue before NMQAAC during its October 1996 meeting and is continuing to gather information and data. Although the agency has concluded that the final regulations should exclude coverage of interventional mammography, FDA expects to propose regulations covering all aspects of interventional mammography in the near future.” Because the profession has considerably more experience with stereotactic breast biopsy since 1996, the FDA should remove this exemption. (2) FDA should not require accreditation specifically for non-stereotactic biopsy interventional procedures (e.g., wire needle localization), since accreditation programs do not exist for these procedures. Instead, FDA should only require that all mammography machines used for non-biopsy interventional procedures be accredited under the basic MQSA requirements. |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.4(c)(5)(i) Review physicians |

Have at least 50% of each year’s practice in breast imaging, be currently actively practicing in the modality reviewed at an MQSA-certified mammography facility, meet the interpreting physician requirements specified in Sec. 900.12(a)(1) and meet such additional requirements as have been established by the accreditation body and approved by FDA. |

Have at least 50% of each year’s practice in breast imaging, be currently actively practicing in the modality reviewed at an MQSA-certified mammography facility, meet the interpreting physician requirements specified in Sec. 900.12(a)(1) and meet such additional requirements as have been established by the accreditation body and approved by FDA. |

It is essential that accreditation body reviewers passing judgment on the performance quality of mammography facilities have considerably more experience than the minimum established by the regulations for physicians interpreting mammograms. Likewise, reviewers evaluating images of a specific modality (e.g., digital) should have current experience with that modality. |

|

900.4(e)(1)(i) |

With its initial accreditation application, the results of a mammography equipment evaluation that was performed by a medical physicist no earlier than 6 months before the date of application for accreditation by the facility. Such evaluation shall demonstrate compliance of the facility’s equipment with the requirements in Sec. 900.12(e). |

With its initial accreditation application, the results of a mammography equipment evaluation that was performed by a medical physicist no earlier than 6 months before the date of application for accreditation by the facility. Such evaluation shall demonstrate compliance of the facility’s equipment with the requirements in Sec. 900.12(e). |

The ACR currently requests only the equipment evaluation results with the initial accreditation application. The FDA has approved this process. |

|

900.4(e)(1)(ii) Reports of mammo equipment evaluations, surveys, and QC |

Prior to accreditation, an annual survey that was performed no earlier than |

Prior to accreditation, an annual survey that was performed no earlier than 14 months before the date of application for accreditation or accreditation renewal by the facility. Such survey shall assess the facility’s compliance with the facility standards referenced in paragraph (b) of this section. |

“Annual” and “or accreditation renewal” should be included to be consistent with other regulations in this part and minimize confusion about what is required. “Six months” should be changed to “14 months” to make this requirement consistent with the current MQSA inspection process as well as the process currently used by ABs. The way it is currently written may force a facility to unnecessarily have more than one annual survey in the same year. |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.4(e)(2)(iii) Reports of mammo equipment evaluations, surveys, and QC |

|

(NONE) |

Inspectors currently review annual surveys and equipment evaluations during the facility’s annual MQSA inspection. The current requirement that facilities also submit annual survey results to the AB each year is a redundant process and an unnecessary burden for mammography facilities. Eliminating this redundancy would allow the AB to focus on obtaining important identification and contact information. |

|

900.4(h)(1) |

Collect and submit to FDA the information required by 42 U.S.C. 263b(d) for each facility when the facility is initially accredited, when notified by the facility and every three years during renewal, in a manner and at a time specified by FDA. |

Collect and submit to FDA the information required by 42 U.S.C. 263b(d) for each facility when the facility is initially accredited, when notified by the facility and every three years during renewal, in a manner and at a time specified by FDA. |

Consistent with the suggested change to 900.4(e)(2)(iii). |

|

900.11(b)(1)(i) Certificates |

In order to qualify for a certificate, a facility must apply to an FDA-approved accreditation body, or to another entity designated by the FDA for accreditation of all mammography units. The facility shall submit to such body or entity the information required in 42 U.S.C. 263b(d)(1). |

In order to qualify for a certificate, a facility must apply to an FDA-approved accreditation body, or to another entity designated by the FDA for accreditation of all mammography units. The facility shall submit to such body or entity the information required in 42 U.S.C. 263b(d)(1). |

Add “for all units” to ensure all new mammography units, including digital, are accredited. |

|

900.11(b)(1)(iii) Certificates |

Facilities must notify their accrediting body of new units and begin accreditation before use. |

Facilities must notify their accrediting body of new units and begin accreditation before use. |

Ensures all new equipment is reported to the accrediting body. |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.11(c) Reinstatement policy |

A previously certified facility that has allowed its certificate to expire, that has been refused a renewal of its certificate by FDA, or that has had its certificate suspended or revoked by FDA, may apply to have the certificate reinstated so that the facility may |

A previously certified facility that has allowed its certificate to expire, that has been refused a renewal of its certificate by FDA, or that has had its certificate suspended or revoked by FDA, may apply to have the certificate reinstated so that the facility may be eligible for a provisional certificate. |

The current wording confuses facilities. In practice, a reinstating facility is not “considered to be a new facility” because they retain their MAP ID number, their MQSA certificate number, and, most importantly, their accreditation history. |

|

900.12(a)(1)(ii)(A) Continuing experience and education for interpreting physicians |

Following the second anniversary date |

Following the second anniversary date in which the requirements of paragraph (a)(1)(i) of this section were completed, the interpreting physician shall have interpreted or multiread at least 960 mammographic examinations during the previous two calendar years. Continuing experience obtained outside of the U.S. is also acceptable. |

(1) The current timeframe for counting this experience has been extremely confusing for personnel and even inspectors. Basing these numbers on calendar years will simplify compliance with no loss of quality. (2) There are a number of instances where physicians who initially qualified in the U.S. under MQSA practice temporarily outside the U.S. and then return. While at a foreign facility they continue to interpret mammograms using the skills they obtained while qualified in the U.S. They should not be prevented from using the examinations interpreted at a foreign site (as long as it is adequately documented) toward meeting the continuing experience requirements in the U.S. upon their return. Currently, FDA guidance prohibits the use of this foreign experience toward meeting MQSA requirements. |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.12(a)(1)(ii)(B) Continuing experience and education for interpreting physicians |

Following the third anniversary date |

Following the third anniversary date in which the requirements of paragraph (a)(1)(i) of this section were completed, the interpreting physician shall have taught or completed at least 15 category I continuing medical education units in mammography during the previous three calendar years. |

(1) The current timeframe for counting this education has been extremely confusing for personnel and even inspectors. Basing these numbers on calendar years will simplify compliance with no loss of quality. (2) Delete “six category I continuing medical education credits in each mammographic modality used by the interpreting physician in his or her practice.” The interpreting physician has already obtained the required initial 8 hours of training to begin interpreting from a new modality. It is more important to allow the physician to select CMEs for continuing experience to help improve breast disease interpretation skills. These do not change with the modality used. |

|

900.12(a)(2)(iii)(A) Continuing education for radiologic technologists |

Following the third anniversary date |

Following the third anniversary date in which the requirements of paragraphs (a)(2)(i) and (a)(2)(ii) of this section were completed, the radiologic technologist shall have taught or completed at least 15 continuing education units in mammography during the previous three calendar years. |

The current timeframe for counting this education has been extremely confusing for personnel and even inspectors. Basing these numbers on calendar years will simplify compliance with no loss of quality. |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.12(a)(2)(iii)(C) Continuing education for radiologic technologists |

|

This continuing education shall include training appropriate to each mammographic modality used by the technologist. |

The current requirement that technologists (and, in effect, continuing education-granting organizations) designate credits with the modality (i.e., screen-film or FFDM) is not reasonable. Most current existing credits are either on general breast disease or specific to screen-film mammography, thus, awarding 6 credits is excessive. They should just be required to include some (as with the original requirements for medical physicists). |

|

900.12(a)(2)(iv)(A) Continuing experience for radiologic technologists |

Following the second anniversary date |

Following the second anniversary date in which the requirements of paragraphs (a)(2)(i) and (a)(2)(ii) of this section were completed or of April 28, 1999, whichever is later, the radiologic technologist shall have performed a minimum of 200 mammography examinations during the previous two calendar years. |

The current timeframe for counting this experience has been extremely confusing for personnel and even inspectors. Basing these numbers on calendar years will simplify compliance with no loss of quality. |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.12(a)(3)(iii)(A) Continuing education for medical physicists |

Following the third anniversary date |

Following the third anniversary date in which the requirements of paragraph (a)(3)(i) or (a)(3)(ii) of this section were completed, the medical physicist shall have taught or completed at least 15 continuing education units in mammography during the previous three calendar years. This continuing education shall include hours of training appropriate to each mammographic modality evaluated by the medical physicist during his or her surveys or oversight of quality assurance programs. Units earned through teaching a specific course can be counted only once toward the required 15 units in three calendar years, even if the course is taught multiple times during this time period. |

The current timeframe for counting this education has been extremely confusing for personnel and even inspectors. Basing these numbers on calendar years will simplify compliance with no loss of quality. |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.12(a)(3)(iii)(B) Continuing experience for medical physicists |

Following the second anniversary date |

Following the second anniversary date in which the requirements of paragraph (a)(3)(i) or (a)(3)(ii) of this section were completed or of April 28, 1999, whichever is later, the medical physicist shall have surveyed at least six mammography units during the previous two calendar years. No more than one survey of a specific facility within a 10-month period or a specific unit within a period of 60 days can be counted towards this requirement. |

(1) The current timeframe for counting this experience has been extremely confusing for personnel and even inspectors. Basing these numbers on calendar years will simplify compliance with no loss of quality. (2) Remove the requirement for two facilities every 24 months. It is becoming more difficult for medical physicists to provide services to more than one facility over a 24-month period. Some facilities do not allow employees to provide outside consulting. In addition, the ratio of units to facilities has increased significantly since MQSA went into effect (1.2 to 1.5). Many large facilities have over 10 units. Physicists have adequate experience surveying mammography units and evaluating QA at one place of employment. |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.12(c)(1)(iv) Medical records and mammo reports—contents and terminology |

Overall final assessment of findings, classified in one of the following categories: (A) “Negative:” Nothing to comment upon (if the interpreting physician is aware of clinical findings or symptoms, despite the negative assessment, these shall be explained); (B) “Benign Finding(s):” Also a negative assessment; (C) “Probably Benign Finding—Initial Short-Term Follow-up Suggested:” Finding(s) has a high probability of being benign; (D) “Suspicious Abnormality—Biopsy Should Be Considered:” Finding(s) without all the characteristic morphology of breast cancer but indicating a definite probability of being malignant; (E) “Highly Suggestive of Malignancy—Appropriate Action Should be Taken:” Finding(s) has a high probability of being malignant; (F) “Known Biopsy—Proven Malignancy—Appropriate Action Should be Taken:” Reserved for lesions identified on the imaging study with biopsy proof of malignancy prior to definitive therapy. |

Overall final assessment of findings, classified in one of the following categories: (A) “Negative:” Nothing to comment upon (if the interpreting physician is aware of clinical findings or symptoms, despite the negative assessment, these shall be explained); (B) “Benign Finding(s):” Also a negative assessment; (C) “Probably Benign Finding—Initial Short-Term Follow-up Suggested:” Finding(s) has a high probability of being benign; (D) “Suspicious Abnormality—Biopsy Should Be Considered:” Finding(s) without all the characteristic morphology of breast cancer but indicating a definite probability of being malignant; (E) “Highly Suggestive of Malignancy—Appropriate Action Should be Taken:” Finding(s) has a high probability of being malignant; (F) “Known Biopsy—Proven Malignancy—Appropriate Action Should be Taken:” Reserved for lesions identified on the imaging study with biopsy proof of malignancy prior to definitive therapy. |

These changes will make the regulations more consistent with the 2003 BI-RADS categories and minimize confusion between the interpreting physician and the clinicians. The FDA has already approved these changes in an alternative standard. |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.12(c)(1)(v) Medical records and mammo reports—contents and terminology |

In cases where no final assessment category can be assigned due to incomplete work-up, “Incomplete: Need Additional Imaging Evaluation and/or Prior Mammograms for Comparison” shall be assigned as an assessment and reasons why no assessment can be made shall be stated by the interpreting physician. For cases rated 0 because of need for prior examinations, reassessment must be performed within 30 days to assign category. |

In cases where no final assessment category can be assigned due to incomplete work-up, “Incomplete: Need Additional Imaging Evaluation and/or Prior Mammograms for Comparison” shall be assigned as an assessment and reasons why no assessment can be made shall be stated by the interpreting physician. For cases rated 0 because of need for prior examinations, reassessment must be performed within 30 days to assign category. |

These changes will make the regulations more consistent with the 2003 BI-RADS category and minimize confusion between the interpreting physician and the clinicians. The FDA has already approved the change in an alternative standard. |

|

900.12(d)(1)(i) Lead interpreting physician |

The facility shall identify a lead interpreting physician who shall have the general responsibility of ensuring that the quality assurance program meets all requirements of paragraphs (d) through (f) of this section. No other individual shall be assigned or shall retain responsibility for quality assurance tasks unless the lead interpreting physician has determined that the individual’s qualifications for, and performance of, the assignment are adequate. Lead interpreting physician must provide regular feedback to technologist on quality of images. |

The facility shall identify a lead interpreting physician who shall have the general responsibility of ensuring that the quality assurance program meets all requirements of paragraphs (d) through (f) of this section. No other individual shall be assigned or shall retain responsibility for quality assurance tasks unless the lead interpreting physician has determined that the individual’s qualifications for, and performance of, the assignment are adequate. Lead interpreting physician must provide regular feedback to technologist on quality of images. |

Data from ACR SOSS surveys suggest 43.8 percent of facilities failing to pass accreditation after three consecutive attempts could benefit from improved physician-technologist communication. Requiring regular feedback may improve quality for facilities overall. |

|

900.12(e)(2)(i) Weekly quality control tests |

The optical density of the film at the center of an image of a standard FDA-accepted phantom shall be at least |

The optical density of the film at the center of an image of a standard FDA-accepted phantom shall be at least 1.40 when exposed under a typical clinical condition. |

Higher contrast films that perform better at higher densities are standard since the final regulations were developed, improving the quality of mammography. The regulations should be changed to reflect this. |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.12(e)(4)(i) Semiannual quality control tests |

Darkroom fog. The optical density attributable to darkroom fog shall not exceed 0.05 when a mammography film of the type used in the facility, which has a mid-density of no less than |

The optical density attributable to darkroom fog shall not exceed 0.05 when a mammography film of the type used in the facility, which has a mid-density of no less than 1.40 OD, is exposed to typical darkroom conditions for 2 minutes while such film is placed on the counter top emulsion side up. If the darkroom has a safelight used for mammography film, it shall be on during this test. |

Consistent with 900.12(e)(2)(i). |

|

900.12(e)(4)(ii) Semiannual quality control tests |

Screen-film contact. Testing for screen-film contact shall be conducted using 40 mesh copper screen. All cassettes used in the facility for mammography shall be tested |

Screen-film contact. Testing for screen-film contact shall be conducted using 40 mesh copper screen. All cassettes used in the facility for mammography shall be tested annually. The test shall also be earned out initially for all new cassettes as they are placed in service, and whenever reduced image sharpness is suspected. |

This is a low-yield test that only needs to be performed annually, and when new cassettes are placed into service, as the majority of rejected cassettes are found upon initial placement into service. |

|

900.12(e)(5)(i)(C) Annual quality control tests |

Automatic exposure control performance. The optical density of the film in the center of the phantom image shall not be less than |

The optical density of the film in the center of the phantom image shall not be less than 1.40. |

Consistent with 900.12(e)(2)(i). |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.12(e)(5)(ii) Kilovoltage peak (kVp) accuracy and reproducibility |

Facilities with older three-phase screen-film systems shall perform the following quality control tests at least annually: (ii) Kilovoltage peak (kVp) accuracy

(1) The lowest clinical kVp that can be measured by a kVp test device; (2) The (3) The highest available clinical kVp,

Newer units with medium- and high-frequency generators will not require this test. |

Facilities with older three-phase screen-film systems shall perform the following quality control tests at least annually: (ii) Kilovoltage peak (kVp) accuracy. The kVp shall be accurate within +/− 5 percent of the indicated or selected kVp at: (1) The lowest clinical kVp that can be measured by a kVp test device; (2) The kVp that is obtained when the accrediting body phantom is imaged with the mammography X-ray unit set to the most commonly used clinical AEC mode; and (3) The highest available clinical kVp. Newer units with medium- and high-frequency generators will not require this test. |

(1) The phrase “most commonly used clinical kVp” often presents confusion because a different range of patient technique settings may be reviewed by the inspector than was examined by the medical physicist. (2) Data from DMIST trials show that this test rarely, if ever, fails during an annual survey. Modern equipment voltage regulation is extremely tight, making this test unnecessary on an annual basis. Reducing the scope of this test during annual surveys would allow the medical physicist to troubleshoot those productive tests that have a higher probability of failing. The test should be retained for equipment evaluations. |

|

900.12(e)(5)(ix) Annual quality control tests |

System artifacts. System artifacts shall be evaluated with a high-grade, defect-free sheet of homogeneous material large enough to cover the mammography cassette and shall be performed for all cassette sizes used in the facility using a grid appropriate for the cassette size being tested. System artifacts shall also be evaluated for all available focal spot sizes |

System artifacts. System artifacts shall be evaluated with a high-grade, defect-free sheet of homogeneous material large enough to cover the mammography cassette and shall be performed for all cassette sizes used in the facility using a grid appropriate for the cassette size being tested. System artifacts shall also be evaluated for all available focal spot sizes, targets, and filters used clinically. |

To assess for image quality and artifacts, only one test of target size, filter, and target is necessary, not combinations. |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.12(e)(5)(xii) Annual quality control tests |

Viewboxes used for interpreting mammograms and clinical image quality review by the technologist should be capable of producing a luminance of at least 3,000 candela per square meter. The illumination levels must be less than or equal to 20 lux. |

Viewboxes used for interpreting mammograms and clinical image quality review by the technologist should be capable of producing a luminance of at least 3,000 candela per square meter. The illumination levels must be less than or equal to 20 lux. |

Viewing conditions are critical in perceiving subtle contrast on film images. The 3,000 candela per square meter is consistent with the 1999 ACR mammography QC manual recommendations. Although the 20 lux value for illumination is lower than the 50 lux recommended in the ACR QC manual, more is known now about the importance of low ambient lighting than was known in 1999 when the manual was written. |

|

900.12(f) Quality assurance-mammography medical outcomes audit |

Each facility shall establish and maintain a mammography medical outcomes audit program to followup positive mammographic assessments and to correlate pathology results with the interpreting physician’s findings. Facilities with the same interpreting physicians should combine medical audit data. This program shall be designed to ensure the reliability, clarity, and accuracy of the interpretation of mammograms. |

Each facility shall establish and maintain a mammography medical outcomes audit program to followup positive mammographic assessments and to correlate pathology results with the interpreting physician’s findings. Facilities with the same interpreting physicians should combine medical audit data. This program shall be designed to ensure the reliability, clarity, and accuracy of the interpretation of mammograms. |

(1) Medical audit data are more meaningful for a facility performing a larger number of examinations. Allowing facilities with the same interpreting physicians to combine their medical audit data across facilities will allow for more meaningful audit data and decrease the burden on individual facilities. (2) Using “should” instead of “may” suggests aggregate data are preferred, but will not result in noncompliance citations for those facilities submitting nonaggregate data. |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.12(f)(1) Quality assurance-mammography medical outcomes audit |

General requirements. Each facility shall establish a system to collect and review outcome data for all mammograms performed, including follow-up on the disposition of all positive mammograms and correlation of pathology results with the interpreting physician’s mammography report. Analysis of these outcome data shall be made individually and collectively for all interpreting physicians at the facility for: (i) Screening examinations, where a positive examination is defined as “Incomplete: Need Additional Imaging Evaluation and/or Prior Mammograms for Comparison,” “Suspicious Abnormality—Biopsy Should Be Considered,” or “Highly Suggestive of Malignancy—Biopsy Should Be Considered,” and (ii) Diagnostic examinations, where a positive examination is defined as “Suspicious Abnormality—Biopsy Should Be Considered,” or “Highly Suggestive of Malignancy—Biopsy Should Be Considered.” (iii) In addition, any cases of breast cancer among women imaged at the facility that subsequently become known to the facility shall prompt the facility to initiate follow-up on surgical and/or pathology results and review of the mammograms taken prior to the diagnosis of a malignancy. |

General requirements. Each facility shall establish a system to collect and review outcome data for all mammograms performed, including follow-up on the disposition of all positive mammograms and correlation of pathology results with the interpreting physician’s mammography report. Analysis of these outcome data shall be made individually and collectively for all interpreting physicians for: (i) Screening examinations, where a positive examination is defined as “Incomplete: Need Additional Imaging Evaluation and/or Prior Mammograms for Comparison,” “Suspicious Abnormality—Biopsy Should Be Considered,” or “Highly Suggestive of Malignancy—Biopsy Should Be Considered,” and (ii) Diagnostic examinations, where a positive examination is defined as “Suspicious Abnormality—Biopsy Should Be Considered,” or “Highly Suggestive of Malignancy—Biopsy Should Be Considered.” (iii) In addition, any cases of breast cancer among women imaged at the facility that subsequently become known to the facility shall prompt the facility to initiate follow-up on surgical and/or pathology results and review of the mammograms taken prior to the diagnosis of a malignancy. |

Combining medical audit data for screening with diagnostic examinations dilutes the meaning of the results and makes it impossible to compare facility/practice performance with current literature or established databases. Furthermore, the ACR BI-RADS Committee believes that a meaningful audit of screening examinations requires that the recommendation for recall imaging (BI-RADS Category 0) also be considered “positive.” These changes will make the regulations more consistent with the BI-RADS follow-up and outcome monitoring guidance. |

|

Regulation |

Additions/ |

Proposed Regulation |

Rationale |

|

900.13(a) FDA action following revocation of accreditation |

If a facility’s accreditation is revoked by an accreditation body, the agency may conduct an investigation into the reasons for the revocation. Following such investigation, the agency may determine that the facility’s certificate shall no longer be in effect or the agency may take whatever other action or combination of actions will best protect the public health, including the establishment and implementation of a corrective plan of action that will permit the certificate to continue in effect while the facility seeks |

If a facility’s accreditation is revoked by an accreditation body, the agency may conduct an investigation into the reasons for the revocation. Following such investigation, the agency may determine that the facility’s certificate shall no longer be in effect or the agency may take whatever other action or combination of actions will best protect the public health, including the establishment and implementation of a corrective plan of action that will permit the certificate to continue in effect while the facility seeks reinstatement. A facility whose certificate is no longer in effect because it has lost its accreditation may not practice mammography. |

After an AB revokes a facility’s accreditation, the facility must take corrective action, have it approved by the AB and reinstate, not “reaccredit.” “Reinstating” requires a facility to submit corrective action for review. |

luminance of at least 3,000 candela per square meter, and should also require that illumination levels be less than or equal to 20 lux. Viewboxes used for clinical image quality review would not need to be inspected.

Personnel

Continuing Education and Experience

Quality standards for mammography personnel include specifications for continuing education and experience. Interpreting physicians are required to read a minimum of 960 mammographic examinations over a given 2-year period as evidence of this continuing experience. Increasing this volume requirement has been discussed as a potential way to improve interpretive quality, yet doing so may inadvertently jeopardize access to mammography services in some areas. Furthermore, current literature remains divided on whether volume alone has a positive effect on physician accuracy in detecting breast cancer (see Chapter 2). Until consensus is reached on the value of interpretive volume, this minimum requirement should remain unchanged.

MQSA-qualified physicians temporarily practicing mammography abroad are currently prohibited from using this foreign experience toward meeting the MQSA requirements. FDA and the ACR have reported requests for clarification on this policy, and, provided adequate documentation is available, such foreign practice should qualify as continuing experience and count toward the volume requirement.

The requirement for six category I continuing medical education (CME) credits in each mammographic modality used should be eliminated for interpreting physicians—only the more general requirement for 15 category I CME units in mammography should remain. Continuing education requirements for physicians should be broadened to allow physicians to select CME courses that help improve breast disease interpretation skills, rather than requiring specific courses in each mammographic modality (see Chapter 2 for more information on improving interpretive performance). However, the requirement for initial training in new mammographic modalities (regulation 900.12(a)(1)(ii)(C)) should remain unchanged.

Similarly, the requirement for modality-specific continuing education should be more flexible for radiologic technologists. The current regulations should be changed to eliminate the specific requirement for six continuing education units in each modality. Instead, regulations for radiologic technologists should more closely parallel those for medical physicists, which require only that “continuing education shall include hours of training appropriate to each mammographic modality.” Because most existing credits are either on general breast disease or are specific to screen-film mammography, radiologic technologists and medical physicists should be required to specifically document only initial training in new modalities, as required in regulations 900.12(a)(2)(iii)(E) and 900.12(a)(3)(iii)(C), respectively. Finally, language describing the timeframe for completion of continuing education and experience should be based on calendar years, to improve clarity.

Continuing experience for medical physicists includes surveys of at least two mammography facilities during the previous 24 months. The number of mammography facilities in the United States has decreased by approximately 9.5 percent over the past 10

years. However, the number of mammography units has increased from 12,076 to 13,652, approximately a 13 percent increase, since 1998 (Destouet et al., in press). Thus the ratio of units to facilities has increased without clear indication of the impact on access, from 1.22 units to facilities in 1998 to 1.52 in 2004, and many large facilities are equipped with more than one unit. It has become increasingly difficult for medical physicists to meet the two-facility requirement, given the number of units at each facility. Sufficient experience is possible from quality control evaluations at one multiunit facility, and FDA regulations should be modified to reflect this.

Physician-Technologist Feedback

Regulation 900.12(d)(1)(ii) addresses the role of the interpreting physician in quality assurance procedures, specifically, taking corrective action when film images are of poor quality. Evidence from ACR site visits suggest radiologic technologists would benefit from improved feedback from physicians regarding image quality; in several instances, technologists have directly requested this feedback.2 Furthermore, facilities with quality problems frequently lack regular communication between interpreting physicians and technologists. Facilities unable to pass ACR accreditation after three consecutive attempts participate in a Scheduled On-Site Survey (SOSS). The ACR team reviewing the facility in question recommends several areas for corrective action; improved communication between radiologists and technologists is suggested in 43.8 percent of SOSS cases (ACR, unpublished). Such improvements for all facilities, not only those under review, may positively impact quality overall.

Regulation 900.12(d)(1) should be expanded to require documentation of routine feedback to technologists from interpreting physicians; documentation of compliance could prove as simple as records of phone calls, e-mails, and quality control meeting minutes. Although a specific regulation requiring documentation may increase facility workload, the Committee agrees that strong communication between radiologists and technologists is an important factor in maintaining quality.

Foreign-Trained Radiologists

The quality of mammography programs abroad, including those in Canada and Europe, has been well documented (Dean and Pamilo, 1999; Hendrick et al., 2002; Elmore et al., 2003). While FDA currently accepts Canadian Board Certification and Canadian residency programs toward meeting initial requirements for interpreting physicians, interpreting physicians obtaining their initial qualifications in any other foreign country (e.g., the United Kingdom) remain effectively excluded from interpreting mammograms in U.S. facilities. FDA should further expand the initial qualification requirements to allow highly qualified interpreting physicians trained in foreign countries other than Canada to interpret mammograms under MQSA.

Ensuring Quality Personnel

Mandatory preceptorship training is typically recommended for mammography personnel deemed to be performing at a substandard level. However, such training can currently be avoided if the individual in question moves to a different facility. The state of Texas accreditation body has reported multiple instances of this, for both interpreting physicians and mammography technologists.3 The initial qualification requirements for interpreting physicians and radiologic technologists should be modified to require documentation of employment history or radiology board qualifications prior to hiring. Individuals with incomplete training requirements should be required to continue and complete training at their new facility. Facilities should practice due diligence and verify employment history prior to hiring new personnel.

Technical Quality

Several quality control tests should be modified to better assess current mammography practice. Optical density (OD) of mammography films is evaluated through weekly quality control tests; FDA inspection data demonstrate few citations for below-threshold OD phantom scores (FDA, 2004a). Additionally, the high-contrast films currently in use require higher optical densities for optimal performance (Hendrick and Berns, 2000). Therefore, the minimum OD requirements should be increased from 1.2 to 1.4. Screenfilm contact tests, previously performed semiannually, should be tested annually, given the low failure rate on inspection (National Mammography Quality Assurance Advisory Committee, 2004). Finally, Digital Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial (DMIST) data show that annual evaluations of kilovoltage peak (kVp) accuracy and reproducibility rarely fail for newer medium and high-frequency generators (Bloomquist et al., submitted). Older three-phase generators should still be tested annually, along with any new unit or equipment recently undergoing major repair.

Medical Audit

Facilities should be required to separate screening and diagnostic medical audit data. Combined screening and diagnostic examination data confound the meaning of the results and make it difficult to compare facility/practice performance with current literature or established databases. Further expansion of the medical audit is discussed at length in Chapter 2. Developing specific regulations to adopt the enhanced audit system recommended in Chapter 2 would be the responsibility of FDA.

The mammography medical outcomes audit currently requires data to be compiled for each radiologist practicing in each separate facility. Facilities with the same interpreting physicians should be allowed to merge the medical audit data for their interpreting physicians. Doing so will result in more meaningful physician data and reduce the burden on individual facilities. Although combined audits would be preferable, FDA inspectors should continue to accept nonaggregate data.

Reports

Mammography letters provided to patients are discussed in regulation 900.12(c)(1). FDA has approved an additional assessment category, “Known Biopsy-Proven Malignancy—Appropriate Action Should Be Taken,” as an alternative standard. This revision should be incorporated into the final regulations because it ensures that the appropriate notification is sent to patients undergoing mammography examinations given that assessment. In addition, each assessment category should also be updated to be consistent with the 2003 Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) categories in order to reduce confusion between the clinician and interpreting radiologist.

Currently, cases where an incomplete workup prevents final assessment should be given a deadline for evaluation. The Committee discussed the possibility of requiring interpreting physicians to resolve all BI-RADS Category 0 assessments (incomplete—requires comparison with previous films)4 within 30 days; however, such a requirement could prove problematic if a patient does not return for a complete workup within that time period. Thus resolution of Category 0 assessment should be required within 30 days for cases where full evaluation only depends on obtaining images from previous mammographic examinations.

According to FDA guidance, a lay summary must be sent to patients when images are compared with previous films, or when an addendum is added to the medical report, even if there is no change in the findings or recommended course of action (FDA, 2005b). Consequently, a lay summary must be sent even if the addendum merely states that the referring physician had been notified of the examination results. This requirement is burdensome on facilities, but more importantly, patients may be confused by receiving multiple letters that do not directly pertain to interpretation of their mammograms. Therefore, FDA guidance should be modified to require a patient letter only when images are reviewed and reinterpreted, even if there is no change in interpretation findings.

Interventional Procedures and New Technologies

Interventional Procedures

Standard mammography equipment is frequently used for interventional procedures, such as preoperative wire needle localization or ductograms. In addition, specialized mammography units can be used by physicians to guide minimally invasive tissue diagnosis procedures such as core needle biopsy. However, nationally recognized standards for such procedures were nonexistent at the time of MQSA implementation, and thus interventional mammographic procedures are currently exempted from regulation by FDA.

In 1997, the ACR and the American College of Surgery (ACoS) developed a joint set of qualifications for physicians performing stereotactic breast biopsy procedures, which included requirements for CME training and continuing experience. These standards became the basis for the ACR’s and the ACoS’s voluntary stereotactic biopsy ac-

creditation programs (American College of Surgeons and American College of Radiology, 1998; ACR, 2004). However, in testimony to the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions on the reauthorization of MQSA, the American Cancer Society noted that of the 4,000 to 5,000 interventional mammography machines in use, fewer than 500 are accredited through the ACR program (American Cancer Society, 2003). Only 11 are accredited by the ACoS program. In similar testimonies, speakers on behalf of the Susan G.Komen Breast Cancer Foundation (Rowden, 2003) and the Society of Breast Imaging (Dershaw, 2003) advocated removing the exemption on interventional mammographic procedures from MQSA.

Furthermore, in the preamble to the final MQSA regulations, FDA noted that “although the agency has concluded that the final regulations should exclude coverage of interventional mammography, FDA expects to propose regulations covering all aspects of interventional mammography in the near future” (FDA, 1997). More than 7 years have passed, and in that time sufficient standards by which interventional breast imaging procedures can be measured have been developed. The Committee urges FDA to promptly remove the exemption of all interventional mammography from MQSA regulations. Specifically, all stereotactic breast biopsy procedures and equipment should be accredited by the appropriate accreditation body. Equipment used for other interventional procedures (e.g., needle localization) should also be regulated by FDA. (While there are accreditation programs for stereotactic biopsy, no programs exist for the other interventional procedures; the Committee believes mandatory accreditation of interventional equipment, not the interventional procedures themselves, is sufficient.) In addition, FDA inspectors should be trained to perform onsite inspections of stereotactic breast biopsy procedures and interventional equipment, as a paper review and review of films obtained by the site would be insufficient for ensuring quality.

Digital Mammography and CAD

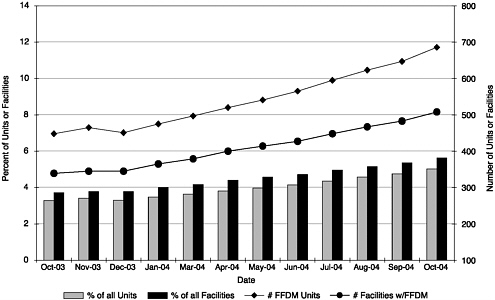

The lack of specific regulation in MQSA for digital mammography is of particular concern because of the increasing prevalence of its use; the number of FFDM units has increased by 4 percent each month over the past year. The number of facilities offering FFDM rose from approximately 320 (approximately 4 percent of all facilities) in October 2003 to just over 500 (6 percent of all facilities) in October 2004 (Figure 3–1) (Destouet et al., in press). Since FDA regulations were enacted in 1999, little action has been taken to delineate oversight of digital mammography. Accrediting bodies are currently approved to accredit the General Electric 2000D, the General Electric DS, the Fischer Senoscan, and the Lorad Selenia FFDM units; other FDA-approved FFDM units (at the time of this writing, this only includes the Siemens Mammomat Novation) are permitted to operate under FDA’s screen-film certification extension policy. Currently, facilities are instructed to adhere to the manufacturer’s quality control manual when operating such devices. This can prove burdensome because the manuals are continually updated and there is little consistency between devices. Only the maximum 300 millirad dosage for a breast of average thickness and tissue composition is specifically covered in the regulations at this time. Regulation 900.12(b) should be expanded to include more specific regulation of digital mammography. Specifically, FDA should develop a uniform set of

FIGURE 3–1 Full Field Digital Mammography (FFDM) growth. Data collected by the American College of Radiology and reported by Destouet et al. (in press) demonstrate an increase in both the number of FFDM units and the number of facilities with FFDM units since October 2003. The percentage of FFDM units and facilities with FFDM units is also represented graphically.

SOURCE: Destouet et al. (In press). Reprinted from the Journal of the American College of Radiology, In press, Destouet JM, Bassett LW, Yaffe MJ, Butler PF, Wilcox PA. The American College of Radiology Mammography Accreditation Program—10 years of experience since MQSA, with permission from The American College of Radiology.

QC tests and test criteria across all digital systems. Uniform standards should not preclude performance of additional tests on some digital systems, as recommended by the equipment manufacturer. MQSA inspectors should be trained to perform onsite inspections of all digital equipment.

Computer-aided detection (CAD) is yet another emerging technology utilized in mammography to facilitate interpretation. However, CAD is software that physicians typically apply to FFDM or digitized film images after the images have been acquired, and may therefore be outside the purview of MQSA. FDA has considered this issue in the past in conjunction with issues surrounding double reading, and came to the conclusion that CAD was not a technology that could be readily dealt with through regulation.5 The Committee concurs with this determination.

Facility Closures

The ACR has reported that between April 2001 and October 2004, approximately 19 percent (1,563 out of 8,325 fully accredited facilities) of their accredited mammography facilities have closed (Destouet et al., in press). Approximately one-third reportedly closed for financial reasons; movement to a sister site, equipment problems, and staffing shortages were also cited as reasons leading to closure. FDA has received a number of complaints from patients who were not informed when their mammography facility closed, and as a result were unable to or unsure of how to access their mammography records (FDA, 2003). Currently FDA guidelines suggest the “facility should make reasonable attempts to inform its former patients of how they can obtain their mammography records [original mammography films and reports],” but no official patient notification is necessary (FDA, 2003). This reflects a serious lapse in patient care. Mammography facilities that close should be required to notify all patients and their doctors of the closure, and should be required to provide information regarding future access to mammography films and reports. However, in cases where facilities are unable to notify patients (e.g., facility bankruptcy), FDA should notify patients and referring physicians on that facility’s behalf.

Enforcement of MQSA

Inspection Testing

Review of FDA inspection data from 2001 to 2003 revealed several inspection areas that could be streamlined, based on the low number of citations issued and the redundancy of the measurements by other entities. Radiation dose is currently measured by the accrediting body and annually by the medical physicist, and measurements rarely fail to meet MQSA regulation. Consequently, FDA should no longer measure radiation dose during inspection; analysis of dose measurements collected by the medical physicist will suffice. Additionally, inspectors should review and score phantom images taken previously by the facility; generation of new phantom images during the inspection is unnecessary. The exposure reproducibility coefficient of variation evaluation should be made only for three-phase units, as the medical physicist evaluates this annually. Half-value layer should no longer be evaluated for the same reason. Inspectors should continue the darkroom fog, collimator, and compression paddle tests due to the relatively larger number of FDA citations during annual inspections. Likewise, the inspectors should continue the processor tests primarily because these are not conducted by the medical physicists (FDA, 2004a).

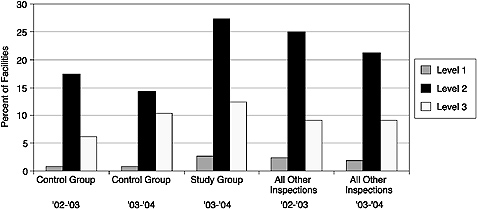

Reducing the frequency of inspections for facilities with good performance records was considered as another way to reduce the burden of MQSA on mammography facilities. As part of the Mammography Quality Standards Reauthorization Act of 1997, Congress gave FDA the authority to organize an inspection demonstration program (IDP) to determine whether MQSA inspections could be conducted less frequently than annually (Mammography Quality Standards Reauthorization Act. Pub. L. No. 105–248 [1998]). Eligible facilities had undergone at least two annual inspections under the final regulations and had received no regulatory (i.e., compliance) actions. After 2 years,

FIGURE 3–2 Percentage of facilities by highest violation level. Data collected from the FDA Inspection Demonstration Program suggest there are a higher percentage of Level 1, 2, and 3 violations at facilities undergoing biennial inspections as compared with facilities undergoing the currently mandated annual inspections.

SOURCE: Adapted from FDA (2005).

compliance data from the control (annual inspection) and study (biennial inspection) groups revealed more Level 1, 2, and 3 violations at facilities undergoing biennial inspections than at the facilities undergoing annual inspections. By percentage, there were more violations at each level for study facilities than there were at all facilities inspected nation-wide (Figure 3–2) (FDA, 2005a). Thus, current evidence suggests that reducing the frequency of inspections, even at historically compliant facilities, would negatively impact mammography quality.

Accreditation Failure

The inability of FDA to require facilities to cease performing mammography after two consecutive unsuccessful attempts at accreditation is another area of concern. The ACR has always strongly recommended that these facilities cease mammography, and has terminated accreditation until these facilities take corrective action and reinstate. Until 2003, FDA required facilities to cease in these cases. In 2003, FDA informed accrediting bodies that they can no longer require facilities to cease mammography if their MQSA certificate is still valid. However, FDA does tell these facilities they “should” cease mammography (FDA, 2004a). In the past year, the ACR has documented two cases in which a facility denied accreditation during the renewal process continued to practice mammography, one for 29 days and the other for 32 days, under a valid MQSA certificate.6 Regardless of MQSA certificate status, facilities failing to reaccredit after two at-

tempts should be required to cease performing mammography until reinstated; FDA should have the authority to enforce this requirement.

Suspensions or Revocations of MQSA Certificates

Regulation 900.13 outlines the role of FDA following the revocation of a facility’s accreditation. Currently, FDA can either declare a certificate “no longer in effect” under Section 900.13, or can fully revoke a certificate under Section 900.14, when a facility’s accreditation is revoked or when the facility is deemed a serious risk to human health. Both regulations prevent the facility in question from performing mammography; as a result, FDA typically invokes 900.13 for timing and efficiency purposes.7 Between 2001 and 2003, FDA declared a facility’s certificate “no longer in effect” once for reasons of accreditation revocation (FDA, 2004b). Although FDA usually requires these facilities to notify their patients and referring physicians of such action (i.e., Patient/Physician Notification), there is currently no public notification system warning consumers in general about such facilities. FDA should require facilities to notify patients and their physicians if the MQSA certificate either is revoked or deemed no longer in effect.

NATIONAL QUALITY STANDARDS

Prior to the enactment of MQSA, the quality of mammography varied tremendously across the United States (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 1990; Galkin et al., 1988). Much of that variation stemmed from differences in the degree that states enacted legislation or regulations to ensure the quality of mammography within their borders. State legislation details requirements in four main areas: equipment specifications, equipment performance testing, facility quality assurance procedures, and personnel qualifications. More than 40 states enacted laws governing mammography quality in one or more areas, although how extensive these laws are varies from state to state. Required enforcement procedures were also variable from state to state (Fintor et al., 1995). MQSA was designed to foster uniform, high-quality mammography throughout the country by providing national standards that would eliminate the need for the patchwork of state regulations governing mammography standards. In recent years, this patchwork has begun to reemerge; vague regulations regarding requirements for accreditation bodies and the role of states has resulted in significant inconsistencies in the regulation of mammography in different states.

Inconsistencies Across Accreditation Bodies

MQSA provides a degree of decentralized oversight of mammography through the accreditation process. As discussed previously, a mammography facility must apply for reaccreditation through a qualified accreditation body every 3 years, once initial accreditation is granted. Currently, the American College of Radiology and the states of Texas, Iowa, and Arkansas have been approved by FDA to act as accreditation bodies. (California was also approved to accredit facilities, but the state’s accreditation program

was closed in late 2003.) However, MQSA sets standards only for the data that accreditation bodies must collect; specific requirements for accreditation vary across accreditation bodies. One particular area of issue is discussed below.

Qualifications for Review Physicians

Qualifications for physicians serving as image reviewers for accreditation bodies should be more comprehensive than the minimum required to interpret mammograms under MQSA. Accreditation body reviewers reviewing the performance quality of mammography facilities should have considerably more experience than the minimum established for physicians interpreting mammograms. The ACR currently requires review physicians to have 5 years of post residency experience in diagnostic radiology, with at least 50 percent of each year’s practice in breast imaging, and be actively practicing in the modality reviewed. Increasing FDA standards to this level is not expected to cause a shortage of qualified review physicians for the state accreditation bodies of Iowa, Texas, or Arkansas. Texas already contracts with ACR-qualified reviewers, and the state of Iowa unofficially applies similar criteria to its own review physicians.8,9,10 Thus, all accreditation bodies should require review physicians to match current ACR review physician criteria.

Inconsistencies Across States

Many states continue to impose regulations beyond those currently required by FDA, which can lead to confusion regarding state requirements for accreditation or certification that conflict with, or are in addition to, federal MQSA requirements. State requirements can also add to the cost of mammography because states that act as certifying bodies can require facilities to undergo additional inspections and can impose additional inspection fees and fines. For example, Missouri charges an additional per-unit fee at every facility in the state (Mo. Rev. Stat. § 192.764 [1992]; Mammography Authorization 19 C.S.R. 30–11.010 [1992]). Evidence is lacking to evaluate the effects of additional state requirements on facility practices, but these measures do not necessarily improve quality, and might detract from the time and resources devoted to breast imaging. The potential for conflict of interest is also a concern because reviewers for state programs generally reside in the same state they are inspecting. Because an increasing number of states are pursuing status as certification bodies, the Committee agreed that this trend warrants close observation.

MQSA regulations cannot supersede those of states; part (m) of the Act specifically states that “Nothing in this section shall be construed to limit the authority of any State to enact and enforce laws relating to the matters covered by this section that are at least as stringent as this section or the regulations issued under this section.” However, because MQSA regulations are so extensive, there may be a compelling reason to

|

BOX 3–2 Federal laws and regulations generally preempt state laws of the same scope if that is the expressly stated intent of the federal law or regulation. An example of such preemption is found in Section 521 [360k] of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA). This section specifies for devices intended for human use, that no states may establish, or continue to enforce, any requirement related to safety or effectiveness that is different from, or in addition to, those the federal act requires. Because the preemption clause in regard to the agency’s regulation of devices was expressly stated, a case brought against the maker of a heart pump was denied. The claim stated that the device caused a death because it was defectively designed and manufactured, as well as inadequately labeled. The Food and Drug Administration considered the design, manufacturing process, and label of the heart pump before it approved the device for marketing; thus its regulation preempted state law tort claims, the court ruled. When national laws or regulations do not specify a preemption clause, they can still preempt state laws if there is implied preemption. Such preemption presides when state law conflicts with federal law. For example, California passed a law called Proposition 65, which requires companies to include in the labeling of their products any chemicals that might cause cancer or reproductive toxicity. Armed with this law, a plaintiff sued the maker of nicotine gum and patches for failing to warn that its products were allegedly known to cause reproductive harm. The California Supreme Court ruled that the state law was preempted because it conflicted with the labeling requirements of the FFDCA. Implied preemption also occurs when federal law is so extensive and pervasive that it can be assumed that Congress did not intend states to supplement it. But it can be waived if state rulings are more comprehensive and traditionally relied on, as was seen in a case regarding the labeling of wines in California. That case hinged on a California law that prohibits the use of the name “Napa” on the label of any wine not made with at least 75 percent of Napa County-grown grapes. This state law was not preempted by federal law because the protection of consumers from potentially misleading brand names and labels of wine is a subject that traditionally has been regulated by the states, the California Supreme Court stated in its ruling. Deference to state rules on wine labels is especially appropriate, the ruling added, considering the importance of the industry to California. Both implied and expressly stated preemption will prevail only if courts find the state law in question governs the same area as the federal law presumed to preempt it. SOURCES: High court (2004); Pitney Hardin LLP (2004); California court (2004); Drug and medical device cases (2002); California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (2003). |

explicitly include a preemptive clause (Box 3-2) in the legislation.11 Replacing part (m) with a reemption clause could help ensure that MQSA regulations are uniformly followed by facilities in all states, largely because these regulations would provide both minimum and maximum requirements for mammography facilities and personnel. An expressly stated preemption clause would also relieve mammography facilities and per-

TABLE 3–2 Self-Reported Estimate of the Cost of MQSA Compliance

sonnel from the burden and confusion of trying to meet both MQSA and state certification and accreditation requirements.

The Committee believes that federal preemption of state standards is necessary. However, this national standard must be flexible in order to facilitate adoption of standards that may advance the quality of breast imaging. Similarly, if a preemption clause is enacted, provisions should be developed to foster the efforts of states that traditionally have been on the forefront of quality improvement initiatives, and to add such approaches to the national standard in a timely fashion.

THE COSTS AND BENEFITS OF MQSA

In 1997, FDA commissioned a study to assess the economic impact of compliance with MQSA Final Rules (Eastern Research Group and FDA, 1997). The Eastern Research Group (ERG) estimated that the average annualized total compliance cost at the time was $38.2 million by “identifying the most typical, least-cost methods of complying with each requirement,” although the report likely underestimated the true cost of compliance. For example, ERG estimated no compliance costs for the medical audit and outcome analysis because project consultants indicated that outcomes analysis was already standard practice at most facilities. However, a recent cost survey conducted by the ACR

indicated that substantial costs are associated with medical audits.12 The ACR collected self-reported cost data from 37 facilities and estimated that the cost of MQSA compliance was $14–$15.70 per mammogram, as shown in Table 3–2. At the time of their study, the FDA estimated that approximately 22.5 million mammograms were performed per year, which translates to $1.70 per mammogram ($2.00 in 2004 dollars). The true cost of MQSA compliance likely falls somewhere between the two estimates from FDA and the ACR. FDA also used a model to estimate health outcomes at various levels of mammography quality (measured by sensitivity and specificity). The report concluded that a 5 percent improvement in quality would have associated annual benefits of between $182 million and $263 million, with 75 fewer annual breast cancer deaths.

It is difficult to estimate the cost of the Committee’s recommendations aimed at improving interpretive quality because costs will vary considerably depending on the current set up of a given facility. For example, facilities that already use software that separates screening and diagnostic exams may be able calculate the required measure with little change. Facilities that do all of their tracking and auditing on paper may find it more expensive to meet the new requirements. Similarly, some facilities already track patients with a BI-RADS 0 assessment, but most do not and thus will experience an additional compliance cost. The added cost of tracking women with 0 assessments will depend in part on the population being served and the recall rate for a particular facility.

Facilities that participate in the voluntary advanced medical audit procedures will likely incur additional costs for data entry, but they will save the time and costs that would be needed to organize and analyze the data (since that will be done by the statistical coordinating center). Also, some facilities may already have established methods of communication with pathologists, whereas others may need to devote considerable effort to establish and maintain adequate communication in order to meet the requirements of the advanced audit. The statistical coordinating center will require funds for staff and infrastructure, perhaps similar to the core costs of the Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium, but ultimately the cost per mammogram will depend in part on how many providers participate in the advanced medical audit program.

It might be useful for FDA to survey all facilities regarding their intentions to participate in the voluntary advanced audits or to seek designation as a Center of Excellence prior to implementation. FDA could also commission another study on the economic impact of compliance with the new medical audit procedures, as they did in 1997.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The final FDA Mammography Quality Standards Act regulations, promulgated in 1999, understandably require revision given the development of mammography practice in recent years. Advancements in technology, particularly digital mammography, require expansion of the current regulations to ensure quality in each mammographic modality. The Committee specifically recommends removing the regulatory exemption on interventional mammographic procedures. The experience of facilities, personnel, and accreditation bodies with MQSA has revealed several areas of overlap that should be addressed; for example, inspection data have demonstrated that several quality control tests are un-

necessary due to redundancy and exceptionally low rates of citation, and therefore could be removed. Regarding enforcement of MQSA regulations, FDA must have the authority to stop facilities from performing mammography following two unsuccessful attempts at reaccreditation, regardless of the validity of that facility’s MQSA certificate. The Committee also recommends that patients and their referring physicians should be notified when a mammography facility either decides to close or has had its MQSA certificate revoked. Finally, the Committee believes that federal preemption of state standards is necessary to preserve the nature of MQSA as a single, unified set of mammography quality standards.

The Committee recognizes that the recommended revisions will require a substantial amount of work by FDA. The regulation revision process is staff-intensive; formal revisions would require solicitation of input from outside scientific and medical experts as well as mammography facilities and practitioners, followed by public hearings and a public comment period. Current guidance documents would also require revision. In addition to the staff costs associated with regulation revision, additional costs would be incurred by FDA following promulgation of the updated regulations. FDA would be responsible for educating facilities, providers, and inspectors about the revisions, and would also be responsible for strengthening enforcement. Therefore, sufficient funding should be made available to FDA for the additional resources and costs associated with revision of the current MQSA regulations.

In short, revision of the current FDA regulations is necessary to ensure that adequate enforcement of quality standards continues, to streamline the inspection process, and ultimately to reduce the burden of inspections on facilities without reducing mammography quality. Screening is only one stage in the process of breast care. Although the purview of MQSA is limited to breast imaging, other chapters in this report more fully discuss how the process of breast care can be improved.

REFERENCES

ACR (American College of Radiology). 2004. Stereotactic Breast Biopsy Accreditation Program. [Online]. Available: http://www.acr.org/s_acr/sec.asp?CID=593&DID=14257 [accessed September 14, 2004].

ACR. Unpublished. ACR Mammography Accreditation Program Scheduled On-Site Surveys: Recommendations for Corrective Action [as of December 2004].

American Cancer Society. 2003. Reauthorization of the Mammography Quality Standards Act. Statement at the April 8, 2003, hearing of the Subcommittee on Aging, Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions, U.S. Senate.

American College of Surgeons and American College of Radiology. 1998. Physician qualifications for stereotactic breast biopsy: A revised statement. Bulletin of the American College of Surgeons 83(5):30–33.

Bloomquist AK, Yaffe MJ, Pisano E, Hendrick RE, Mawdsley GE, Bright S, Shen SZ, Mahesh M, Nickoloff E, Fleischman R, Williams M, Maidment A, Biedeck D, Och J, Seibert AB. Submitted. Quality control for digital mammography in the ACRIN DMIST trial. Medical Physics.

California court ruling could set legal precedent. 2004 (April 26). Washington Drug Letter. 36(17).

California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment. 2003. Proposition 65. [Online]. Available: http://www.oehha.org/prop65/background/p65plain.html [accessed December 8, 2004].

Dean PB, Pamilo M. 1999. Screening mammography in Finland—1.5 million examinations with 97 percent specificity. Mammography Working Group, Radiological Society of Finland. Acta Oncologica 38(Suppl 13):47–54.