Executive Summary

In response to a request from the Department of the Navy, the National Research Council, under the auspices of the Naval Studies Board, established the Committee on Naval Analytical Capabilities and Improving Capabilities-Based Planning to conduct a workshop on Navy analytic methods and capabilities-based planning (CBP) activities. The committee was tasked to address key elements of CBP, examine Navy analytical processes, assess current Navy CBP processes and evaluation tools, and recommend an approach to making improvements. The study effort was to be short term, with a relatively rapid response provided to the Navy.

NAVY CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITY

Current U.S. defense strategy calls for the capability to deal with the full spectrum of current and future threats within the limits of available financial and personnel resources. In the past 15 years, the Department of Defense (DOD) has faced a constant stream of new challenges. Now, rather than being prepared to face a major Soviet threat and a few major regional contingencies (e.g., North Korea) in conventional warfare scenarios, the United States must be prepared both to deal with a larger number of more diverse threats with varied attributes and to do so in circumstances involving complex and uncertain risks. Many of the challenges were laid out in the 2001 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR), which introduced the emphasis on capabilities-based planning.1 The DOD has also

|

1 |

Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. 2001. Report of the Quadrennial Review, Department of Defense, Washington, D.C., September. See also information available at <http://www.mors.org/cbp/read/AA-Korean-Presentation-Early-Spr.pdf>. Last accessed on October 18, 2004. |

emphasized jointness and initiatives to transform U.S. military forces so that they may better cope with the new challenges, including threats from non-nation-states.

As follow-up to the QDR, the Secretary of Defense commissioned a task force—the Joint Defense Capabilities Study Team—led by the former Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, which recommended “a capabilities-based process for identifying needs, creating choices, developing solutions, and providing capabilities.”2 In October 2003, the Secretary of Defense accepted many of the recommendations that appeared soon thereafter in the final, published report of the task force and issued implementing guidance for adopting CBP in the budget development process.3

Although the basic principles of capabilities-based planning and analysis are not new, they have not been emphasized within the DOD in recent decades. Even today there is no consensus within the department about precisely what CBP is and what its essential elements are. This report gives the committee’s view and seeks to contribute to the development of such a consensus. Basically, the challenge for the DOD and the Navy is, within fiscal constraints, to improve the development and execution of programs so as to ensure that they produce fully integrated joint warfighting capabilities in support of missions assigned to combatant commanders in the present or in the future. This challenge requires the management of complex risks within planned DOD funding levels to the satisfaction of the President and the Secretary of Defense.

The Navy has an opportunity to lead the Services as it improves its own internal CBP, analysis, and resource allocation efforts. The Navy can build on a historical legacy of analysis and of complex integrations across multiple functional areas, such as that of implementing layered defenses for antisubmarine and antiaircraft warfare.

WHAT IS CAPABILITIES-BASED PLANNING?

As there is no official government definition of the term capabilities-based planning, the committee adopted the following for purposes of this study: “Capabilities-based planning (CBP) is planning, under uncertainty, to provide capabilities suitable for a wide range of modern-day challenges and circumstances while working within an economic framework that necessitates choice.”4

Although concise, this definition highlights the need to deal with massive uncertainty (about both scenarios and details of assumptions in those scenarios) and to do so while considering a range of competitive options and trade-offs before making the choices necessitated by a budget. The definition given here reflects the committee’s focus on future force/program planning and the resources for achieving it rather than on operational planning.5 Capabilities-based planning may also be defined so as to include adaptive planning more explicitly.

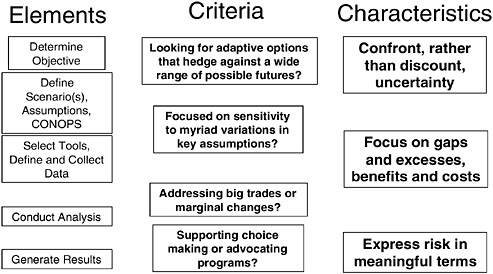

The committee’s review of the Navy’s methods included looking at whether major strategic choices and trade-offs are being assessed with due regard for the element of uncertainty and whether there is concern about ensuring strategic adaptiveness to deal with currently unexpected developments. Figure ES.1 summarizes the key elements and criteria for carrying out capabilities-based planning.

NAVY-WIDE ENABLERS

This Executive Summary is organized in terms of two specific enablers of capabilities-based planning:

-

Frameworks, tools, and their use—the conceptual framework, the analytic framework (including the building blocks of capability), and related methods and tools of analysis such as modeling and simulation; and

-

Personnel and organizations—the resources for performing and managing key activities.

The Navy needs to address these enablers for its CBP activities both inside the Department of the Navy and within the larger DOD environment. In this report, the committee treats challenges inside the Navy separately from those for the Navy operating in the larger DOD environment, even though many of the

|

|

p. xi. Explanatory note: Current capabilities-based planning is very different from what became standard practice in the DOD over the past 20 years, but in some respects it harkens back to principles espoused in the 1960s (see, e.g., Charles J. Hitch and Roland N. McKean, 1965, The Economics of Defense in the Nuclear Age, Holiday House, New York, N.Y.). In other respects, current capabilities-based planning is different from the classic ideas of that era. For example, in the 1960s, sharp lines were drawn separating declaratory policy, programming, and operations. Today, efforts are being made to integrate them coherently. In addition, jointness was much less developed then than it is today. And, certainly, at that time analytical methods and computers did not permit either broad exploratory analysis or high-resolution detailed analysis of the sort that is possible today. |

|

5 |

See Chapter 4 for full definitions of these terms. Briefly, future force/program planning is the process by which the DOD builds its biennial budget proposals for the funding of future capabilities, whereas in operational planning, operational commanders devise and promulgate courses of action for any number of possible situations requiring the use of military capabilities currently available. |

FIGURE ES.1 Key elements, criteria, and characteristics for carrying out capabilities-based planning. NOTE: CONOPS, concept of operations.

same suggestions apply in both situations. It does so because the Navy can control what it does internally but can only hope to influence the broader DOD CBP activities led by the Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (OJCS). This latter situation is significant because the OSD and the OJCS capabilities-based planning activities are in a state of development, as are those in the Navy. Internally the Navy should carry out highly competent CBP, and in the broader DOD community it should be an integral participant, both by doing well what is required (by guidance from the Secretary of Defense) and by helping to further develop an integrated DOD process. However, the Navy should not delay in making internal improvements if the broader DOD community is slower in developing good CBP activities, is not as well focused, or cannot achieve consensus about the direction it will take.6

|

6 |

Any of these eventualities could be likely in the broader DOD community, given the current lack of consensus on CBP priorities and activities across different elements of the DOD (as observed by committee members in this effort and elsewhere). A former Deputy Secretary of Defense is said to have commented that when a decision is made in industry, subordinates go about implementing it, whereas a decision in government is seen as the beginning of a dialogue. (See also the section entitled “The Navy’s Current Problem and Challenge” in Chapter 1 of this report.) |

Inside the Navy

Assessment of Frameworks, Tools, and Their Use

The criterion of the committee for its assessment of current Navy CBP processes, tools, and related activities is whether the Navy possesses and is using the appropriate frameworks and tools for CBP. Its summary assessment, described more fully in Chapter 3, is mixed. The committee considered issues under the categories of “conceptual framework” and “analytic framework.” It considered matters at the top level of the Secretary of the Navy and the Chief of Naval Operations, at the supporting staff level of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV), and at the level of system commands.

Conceptual Framework. The committee concludes that the top level of the Navy has done a creditable job in laying out a broad strategic approach under Sea Power 21. The committee is also encouraged by the evidence of managerial rethinking about organization, process, and products to support CBP at the systems command (SYSCOM) level and by the organization of a Virtual Systems Command to increase agility and integration. At the level of OPNAV studies and analysis, however, the committee finds a disconnect and a number of reasons for concern. While top-level documents and briefings emphasize jointness and the need to address a broad range of general scenarios and cases within them, the OPNAV work that the committee saw ultimately relied upon point-scenario analysis inconsistent with CBP principles. Further, it appeared that this work reflected the conceptual framework in which studies were being developed.

Analytic Framework. At the mission and operational levels, the committee saw clear examples of generic problems which often beset DOD analysis that is intended to support capabilities-based planning but actually does not. These problems include the following: trivializing of issues involving uncertainty and exploratory analysis, focusing on the scenario details preferred by the organization (e.g., those that dramatize the organization’s role and needs) rather than presenting a more holistic view, and relying upon large, complex, inflexible models and databases, which often bury issues and preclude exploration.

The Navy’s analysis of its aggregate-level capability needs also has problems (which exist within the broader DOD community as well).7 The committee

is encouraged by the fact that parts of the Department of the Navy are now vigorously pursuing concepts, previously off the table, for improving aggregate effectiveness (e.g., the Fleet Response Plan and rotational crews). However, it is also concerned that such innovations are not appearing in higher-level capabilities analyses.

Based on what the committee saw and heard, it has a major concern related to the Navy’s ill-developed analytic framework for portfolio-management-style analysis (i.e., strategic-level portfolio analysis for the Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) and other senior leaders).8 The committee’s view is that the analyses and presentations provided to top decision makers should have a more strategic, top-down character, and should more explicitly address economic choices and trade-offs. Certainly, they should identify shortfalls as they do now, but they should also more explicitly identify opportunities, efficiencies, and sources of funding. They should better illuminate risks and ways to mitigate or otherwise manage and balance the risks. Developing appropriate portfolio views is complex and highly dependent on the particular issue and decision context. It requires a broad spectrum of analytic capability guided by a higher level of thoughtful, strategic analysis than that typically associated with operations research or even systems analysis. This need is addressed further in the following subsection, “Assessment of Personnel and Organizations.”

Recommendation 1: The Chief of Naval Operations should reiterate principles of capabilities-based planning and ensure that they are truly assimilated in Navy analytic processes.

The criteria for implementing Recommendation 1 include the following: The work accomplished should be joint and output-oriented, with the ability to actually execute operations as output. Successful CBP will require analysis over a broader scenario space, extensive exploratory analysis within selected scenarios, development of options both to solve capability problems and to achieve efficiencies, and portfolio-style assessments of those options at different levels of detail. The portfolio-style assessments should assist in making decisions on trade-offs and should address various types of risk that Navy leadership must take into

|

8 |

The precepts of portfolio-style analysis are discussed in detail in Chapter 3. Portfolio-management analysis is the combination of hard analysis with judgment and with qualitative, value-laden trade-offs across goals—matters that are in the province of top decision makers. This combination of hard analysis with judgment may be facilitated with appropriately structured scorecards that provide holistic views of how options fare under the varying criteria that top decision makers care about. Related, spreadsheet-based tools can enable such work, provide an audit trail to assumptions, and assist in exploring the consequences of different decision-maker perspectives on the ranking of alternatives for effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. See also Richard Hillestad, Jr., and Paul K. Davis, 1998, Resource Allocation for the New Defense Strategy: The DynaRank Decision Support System, RAND, Santa Monica, Calif. |

account. Strategic options should be adaptive, because world developments and technological developments will undoubtedly force changes, the potential need for which is not much discussed in the DOD’s Strategic Planning Guidance.9

The committee is quite aware that analytic organizations have trouble responding to the demands of good capabilities-based planning. The difficulties are rooted in excessive dependence on large, complex models and related databases; in demands for detail by managers; and in the ways that analyses have been framed and conducted. Breaking these molds will not be easy. It will require a family-of-models approach and new model building. Part of this process must include “smart,” low-resolution modeling and analysis (grounded in higher-resolution work or empirical data when appropriate) that puts a premium on higher-level insights rather than focusing on minutia.

Recommendation 2: The Chief of Naval Operations and the Secretary of the Navy should ensure that the Navy invests in defining and developing the new generation of analytic tools that will be needed for capabilities-based planning.

Some of the attributes needed in tools include the following: agility in low-resolution modeling coupled with the ability to go into greater depth where needed (achievable with a sophisticated family of models and games); the ability to represent network-centric operations well (including publish-subscribe architectures, rather than node-to-node representations); and the ability to deal with challenges such as those that the OSD refers to as disruptive, catastrophic, and nontraditional scenarios.

The committee is aware that the CNO has funded new work on a family of models. It is quite possible, however, that the funds will quickly be exhausted in improvements to “big models” and databases, with little benefit for higher-level capabilities-based planning, as described above. The committee encourages a balanced application of funds, including the potential purchase or use of available off-the-shelf tools.

It is not possible for the committee to make more detailed suggestions here without a more extensive study. The committee notes, however, that examples of the kinds of tools mentioned above have been developed and applied.

Assessment of Personnel and Organizations

The criterion of the committee for its assessment of current Navy CBP processes, tools, and related activities in the area of personnel and organizations

is the ability of personnel and organizations to implement CBP principles. The committee’s summary assessment in this area is also mixed.

The committee is encouraged by the progress made on approaches being taken in the Office of the Deputy Chief of Naval Operations (DCNO) for Manpower and Personnel (N1) and the Office of the DCNO for Fleet Readiness and Logistics (N4) with regard to personnel analyses, and by the work being done in N4 to better relate resources to readiness levels and to provide analytically based trade-off options to the CNO. The committee is also encouraged by the work presented to it by the Space and Naval Warfare Systems Command (SPAWAR), the Naval Sea Systems Command (NAVSEA), and the Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR), including a description of the Virtual Systems Command intended to provide integrated options and information across the previously more vertically oriented systems commands. The presentation by the Navy Warfare Development Command (NWDC) was also oriented toward some of the larger issues that need to be addressed in good capabilities-based planning, albeit with a near-term focus.

During its workshop, the committee also saw some competitive analyses work done by the Assessments Division of the Office of the DCNO for Resources, Requirements, and Assessments (N81) that related to earlier work done by the Warfare Integration Division of the Office of the DCNO for Warfare Requirements and Programs (N70). The idea and use of competitive analysis and creative tension can be productive, and the intention of generating alternative perspectives is always commendable. However, the competition between parts of the Office of the DNCO for Warfare Requirements and Programs (N6/N7) and the Office of the DNCO for Resources, Requirements, and Assessments (N8) does not appear to be helpful and involves high opportunity costs. What the committee observed during discussions with these two groups were two alternative, ad hoc views of the issue and the results of two undocumented analyses. It would be better if the Navy were to produce for the CNO an objective, well-structured analysis informed by alternative points of view. Such an analysis would be more comprehensive, systematic, parametric, questioning of assumptions, and transparent than what the committee observed.

A particularly deficient element in the Navy’s current ability to support capabilities-based planning relates, as mentioned above, to providing options for choice in portfolio-style analysis modules suitable for decision making by the CNO and the Secretary of Defense.

Presenting broad, discerning, strategic-level analysis for the CNO requires a higher level of analysis than that characteristic of operations research or systems analysis. This broad analysis is in the realm of strategic planning and policy analysis. It requires a strategic sense, questioning of assumptions (even of “blessed” assumptions), applied common sense, and critical review of “how much is enough.” This capability, in turn, requires having a mix of multidisciplinary warriors, policy analysts, systems analysts, engineers, economists, and managers

(perhaps with master’s degrees in business administration), who can effectively apply the right tools to the issues at hand. Current personnel “requirements” for OPNAV analysis are predominantly limited to capabilities and experience possessed by operations-research-oriented personnel. Those requirements need to be expanded. The committee believes that the Navy needs to change some current manpower and personnel policies to enhance its ability to build a longer-term, high-quality OPNAV staff with enhanced capabilities to perform excellent capabilities-based planning and analysis. A key element of those changes should involve creating career paths for future leaders in order to introduce such individuals early to the discipline of analytical thinking in a real-world context (e.g., the analysis for, preparation of, and review of the Navy Program Objective Memorandum (POM) and/or equivalent parts of the overall DOD program). Such career paths should continue to expose such individuals to the world of analysis and trade-offs in which outcomes influence budgets and/or major programs.

Where should such higher, strategic-level analysis be performed within the Navy? If the Chief of Naval Operations and the Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) are to benefit fully from a first-rate analytical organization, then it is essential that the organization—

-

Be able to report directly, or relatively directly, to the CNO/SECNAV (rather than being relegated to low levels in the Department of the Navy with layering to dilute its influence);

-

Be institutionalized, so that it cannot easily be disbanded; and

-

Be close to program builders to ensure that it reflects the reality of the issues that the decision makers must address, including funding limitations.

Whether these criteria can be met within the current OPNAV organization was not something that the committee could easily assess in the time allotted for this study. The committee has thus refrained from making specific organizational recommendations in this area. However, the committee makes the following two substantive recommendations based on the relevant government service experience of a number of its members as well as the committee’s collective knowledge of the Navy, good practices in government, and good practices in industry.

Recommendation 3: The Chief of Naval Operations and the Secretary of the Navy should develop a clearly delineated concept of the Navy’s future senior-level analytic support organization and define goals for its composition, including multidisciplinary orientation and officers appropriate for high positions.

The CNO and the SECNAV should insist on having analysis and presentation of decision packages that are as close to objective as possible, and on having the ready means to obtain special independent assessments on important issues when needed. In Chapter 3, the committee briefly discusses several historic mod-

els used in different Services to achieve this goal. No recommendations on a specific model would be possible without more study. In any case, the committee believes that the CNO and the SECNAV should take the time and effort necessary to ensure that they are obtaining the best analytic support possible. How they choose to organize for meeting this need could be the most important decision they make regarding the future success of the Department of the Navy’s capabilities-based planning for a decade or more.

It will take considerable time to implement any decision made on this issue. Thus, the committee offers suggestions to assist the Navy for the short term.

Recommendation 4: In the short term, the Chief of Naval Operations and the Secretary of the Navy should go outside their organizations to sharpen concepts and requirements, drawing on the external community of expert practitioners in analysis. Also, they should augment their in-house analytical capabilities in the short term by drawing on Intergovernmental Personnel Act assignments (and other individuals who could take leave from their home organizations), Federally Funded Research and Development Centers, and national and other nonprofit laboratories.

Within the Larger Department of Defense Environment

Background

As discussed in Chapter 4, the committee recognizes that the DOD’s capabilities-based planning is not yet fully defined. Indeed, it is both complex and confusing to participants. Nonetheless, it is the primary process that the Secretary of Defense is currently using to guide and assess Service program proposals. It is therefore important for the Navy to assume a strong role both in influencing the DOD process as it evolves and in structuring Navy program proposals in ways that are responsive to the guidance from the Secretary of Defense.

Assessment of Analytic Frameworks, Tools, and Their Use

The criterion of the committee for assessment of the use of analytic frameworks and analytic tools within the larger DOD environment is whether Navy frameworks and uses of these tools are suitable for effective work in the larger DOD environment. The summary assessment of the committee on this issue is generally negative.

The CNO’s guidance to the Navy for 2004 emphasizes joint capabilities. However, in presentations at its workshop, the committee saw very little evidence of jointness in the process that the Navy uses to develop its multiyear program plan. While the Navy has done a creditable job in laying out a broad strategic approach for its own analysis and for allocation of resources, that approach is

organized under the top-level components of Sea Power 21.10 There is not yet adequate linkage between the Sea Power 21 framework and the evolving DOD capabilities-based planning framework being developed under leadership from the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the Office of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. This dichotomy is recognized by the Navy, as discussed in Chapter 4 (see Figure 4.5). However, the lack of a clear mapping from the Navy’s decomposition of defense functions to the broader DOD decomposition of such functions is a potential source of a major problem that may jeopardize the Navy’s credibility and effectiveness in the broader DOD capabilities-based planning and analysis processes. If this mapping problem cannot be resolved (by developing adequate crosswalks and/or by the Navy’s influencing the structure of the DOD functional decomposition), the Navy may need to drop or modify its Sea Power strategic approach for its capabilities-based planning, analysis, and resource allocation efforts. It is too soon to reach a conclusion on this subject, and the Navy leadership should assess it on a periodic basis to determine if a major shift is required.

In its brief workshop, the committee also was shown no evidence of the integrated Navy and Marine Corps program planning and analyses that one would expect if the Department of the Navy was attempting to optimize its investment in such combined forces. The naval forces taken together, after all, have remarkable current and potential capabilities.

The Navy also has a long history of conducting detailed quantitative analysis at several levels of aggregation in support of both Navy program planning and the operational planning of naval component commanders. However, as mentioned above, as of mid-2004, Navy campaign analyses briefed to the committee were structured around scenarios that the Navy believes are appropriate for its purposes but that do not fully conform with the defense planning scenarios specified by guidance from the Secretary of Defense for department-wide program planning. While the Navy should certainly explore scenarios and cases that depart substantially from the DOD’s baseline cases (as the guidance encourages), the credibility and effectiveness of the Navy within the DOD are jeopardized by the Navy not clearly assessing its proposed capabilities in the Secretary of Defense’s mandated baselines.

On a related matter, the committee is struck by the apparent lack of Navy analysis of homeland defense (i.e., the direct defense of the United States against external attack), which is described in the Secretary of Defense’s guidance as the department’s highest priority. With the exception of its program to increase the capability of its Aegis ships to detect, track, and possibly engage a larger spectrum of cruise and ballistic missiles, the committee saw no evidence of Navy programs that directly address homeland defense.

|

10 |

See Chapter 3 and, in particular, Figure 3.1. |

Recommendation 5: The Chief of Naval Operations should direct that Navy force planning consistently include use of the baseline scenarios (including concepts of operations, threat assessments, and so on) specified by the Office of the Secretary of Defense. The Chief of Naval Operations should also work with the Secretary of the Navy and the Commandant of the Marine Corps to establish a more integrated, joint Navy/Marine Corps Program Objective Memorandum development process that could serve as a model for the Department of Defense more broadly. Navy force planning should also include extensive exploration to lead to better understanding of the consequences of scenario details and other assumptions of analysis.

Of course, within the extensive exploration recommended above, Navy planning should address in particular depth those scenarios and the cases within them that affect Navy missions, capabilities, and needs. The point here, however, is that to be a credible joint participant, the Navy should address the DOD’s standard baseline cases. Navy leadership should also reassess periodically its success or failure in getting adequate linkage between Navy and DOD-wide decompositions of defense functional capabilities and adjust its program as necessary to be fully effective in the broader DOD capabilities-based planning and analysis processes.

Assessment of Personnel and Organizations

The criterion of the committee for its assessment of the effectiveness of Navy personnel and organizations in the larger DOD environment is the quality of Navy participation and influence in the OSD- and the OJCS-led capabilities-based planning efforts. The summary assessment of the committee in this area is mixed to negative.

During the workshop, Navy briefers described their organizations’ attempts to cover all the bases in CBP meetings called by OSD and OJCS personnel, but indicated that the organizations had insufficient resources to participate fully and effectively. Some lack of coordination and of internal Navy scheduling control was also evident. This may be due in part to the lack of clarity in OPNAV lines of responsibility for CBP activities; that lack sometimes results in a duplication of effort. In addition, other information provided to the committee indicates that the Navy is not always well represented in the DOD joint CBP processes. Several non-Navy briefers noted that Navy representatives on the various boards and committees are often unfamiliar with the issues, not empowered to speak on behalf of the Navy, or absent. Regardless of whether these difficulties result from insufficient staff resources or other problems, they preclude justice being done regarding naval issues in the larger DOD environment and undercut Navy interests in competition for both influence and funding.

Recommendation 6: Over the longer term, the Chief of Naval Operations should identify and staff a central activity that is charged with the responsibility for harmonizing the Navy’s capabilities-based planning processes with those of the larger Department of Defense (DOD) force planning community, and should staff that activity to represent Navy interests effectively in the DOD joint planning activities.

Currently, the most logical place for this assignment would be in the Office of the DCNO for Resources, Requirements, and Assessments, because the processes involved in capabilities-based planning include resource-allocation issues across all force and support areas. However, the decision on how best to accomplish the tasking for such a central activity should logically follow from or be consistent with the model chosen by the CNO to ensure having a highly competent analytical group to support the CNO in all aspects of capabilities-based planning. In the short term, to achieve the best possible utilization of resources, a possible solution would be to designate one individual (e.g., the director of the Navy staff) to be responsible for resolving any capabilities-based planning coordination problems within the OPNAV staff.

FUTURE EFFORTS

Chapter 5, “Potential Future Efforts,” summarizes important sources of information that the committee was not able to investigate during this “quick-look” effort. It also identifies additional areas for further investigation that could be of benefit for the Navy to improve its capabilities-based planning.