1

Why Teens Stay Up All Night and Sleep All Day

When my friend Joan’s daughter was in high school, a constant battle raged between her and her mother. Fifteen-year-old Sarah followed a full day of classes with either a piano lesson, a tennis team practice or match, or a meeting of one of the many clubs she belonged to. Then, of course, there was dinner, phoning or IMing friends, working on one of the craft projects she loved to create, watching a little TV, plus hours and hours of homework. Most nights Sarah didn’t hit the sheets until midnight at the earliest—and then could barely be roused to make it to school on time the next morning. Joan was more than a little concerned that the five and a half to six hours of sleep Sarah routinely logged wasn’t close to the amount she needed and constantly urged Sarah to change her routine and go to bed earlier.

Sarah would have loved to feel less exhausted every school morning, but she enjoyed every one of her activities and refused to give anything up. She also told her mom that even if she wasn’t involved in sports and music and clubs and didn’t have tons of homework to do, she wouldn’t be able to fall asleep any earlier. On the rare evenings when she did have less homework or didn’t spend as much time online with her friends, she tried to go to bed a little earlier but nothing happened—she would just lie there getting frustrated until she finally fell

asleep close to the usual time. Sarah told her mom that she simply didn’t feel tired before midnight or 1:00 in the morning.

Hard as this was for my friend to relate to—Joan herself was so tired in the evenings after working all day at her public relations job, making dinner for her family, helping her younger kids with homework, and doing all the household and family things that needed to be done that day that she was more than ready to collapse by 10:00 p.m.—Sarah wasn’t being a stubborn, defiant adolescent (OK, maybe she was being a little stubborn). Like most teenagers, she didn’t feel the urge to sleep until well into the night. She would have loved to sleep all morning, and did sleep till close to noon on the weekends, but she just couldn’t manage to fall asleep at what her mom considered a reasonable hour.

A TEEN’S TAKE

“I’m convinced I need sleep—I just choose not to do it. There’s a lot going on in my life, but giving up activities isn’t the answer. Being up late is a social aspect of being a teenager. You want to talk to your friends and go online at night. If you took this away it would be like cutting out half your life.”

Does this scenario sound familiar? Most likely it does. I hear similar stories daily in my practice, and I’ve lived through similar scenarios with my own kids. Teenagers just about everywhere struggle with the negative effects of lack of sleep, but even when their schedule permits it they can’t seem to get to sleep early enough to get all that they need before the alarm goes off in the morning. We, as parents, could easily argue that our kids have time-management issues and that they could talk with their friends after school and in the early evening and still have plenty of time to do their homework. But the problem is that they feel most awake, alive, and ready to socialize late at night.

The reason? As we’ll talk about in Chapter 5, today’s competitive 24/7 world makes it hard for teenagers to turn off and tune out. But a major contributor to most teens’ tendency to stay up all night and sleep all day is the chemistry of their brains. Studies show that, while children’s and adults’ brains are wired to follow a sleep-wake cycle that makes them sleepy in the mid- to late evening and wakeful first thing

in the morning, teens’ brains signal both sleepiness and wakefulness at much later times.

|

WHAT’S YOUR TEEN’S NUMBER? The National Sleep Foundation (NSF) says that adolescents need between eight and a half and nine and a half hours of sleep every night to function optimally but that 85 percent get only six. How many hours of sleep a night does your teen usually get? To see where she falls on the sleep deprivation scale, encourage your teen to take one of the sleepiness tests in Chapter 6 or to keep a sleep log (see Chapter 8) for a week or two. |

The Changing Brain

Until recently, scientists believed that the human brain was nearly fully developed by the time its owner reached the age of 3. Babies are born with most of the brain neurons they’ll ever have, and unnecessary cells are weeded out during the last several months of gestation. By age 3, it was thought, the brain was pretty much a finished, polished product.

Not so, we now know—the brain continues developing well into the 20s. Dr. Jay Giedd, a neuroscientist at the National Institutes of Health, has led a number of studies that show that the brain undergoes enormous change around the time of puberty, a thinning or “pruning” of neurons, or nerve cells, that doesn’t stop until about age 25. Giedd has found that other changes, from a speeding up of neural transmissions to growth in several key areas of the cerebral cortex, occur in the brain as well. From these and others studies, it’s clear that the teenage brain is still very much a work in progress.

Part of this ongoing brain development is evidenced in the adolescent tendency to fall asleep and wake up later than other folks. Chemicals in the brain, called neurotransmitters, send and receive messages, some of which signal when it’s time to go to sleep and others when it’s time to wake up. For example, norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, and hypocretin promote alertness and keep the brain awake. Cholinergic transmission is involved in wakefulness and rapid eye movement

sleep. Gamma-amino-butyric acid, or GABA, encourages sleep, and melatonin cues winding down in anticipation of sleep. While we are just beginning to understand the highly complex functioning of the sleep-wake cycle at a biochemical level, we do know that it is the dynamic balance of these neurotransmitters in pathways deep in the brain, plus the summary effect they have on a regulatory brain region called the hypothalamus, that puts us at a particular point along the sleep-wake continuum at a particular point in time. Behavior, genetics, light, and the myriad changes associated with puberty also influence the set point for sleep onset.

A TEEN’S TAKE

“ When I was younger I really, really wished I could stay awake to watch the ball drop on New Year’s Eve like everyone else. Then, one summer, I was just able to sleep till 10 in the morning and it was so much easier to stay up at night. Now it’s no problem at all.”

Children who haven’t yet gone through puberty receive these neurochemical sleep-wake signals at times appropriate to, and synchronized with, the day-night cycle. For example, their melatonin production is set in motion in the late afternoon as daylight fades, triggering the onset of the process that eventually produces sleep. Adolescents who have embarked on the puberty trail, however, receive these hormonal signals later in the evening, even though they require the same amount of sleep as their prepubertal friends. Teenagers and younger 20-somethings naturally stay up later because their pineal gland secretes melatonin later, which causes them to fall asleep later than children and adults. Studies done by eminent sleep researcher Mary Carskadon also suggest that the later secretion of melatonin may cause teens to sleep on and on in the morning.

The delayed sleep phase of adolescence.

|

IDENTIFYING LATER DIM LIGHT MELATONIN ONSET To determine if kids are receiving their melatonin signals later, it helps to understand where they are in their sexual development. Many doctors make this determination using the Tanner Stages or Tanner Scale (sometimes called the Sexual Maturity Ratings). Developed by pediatric endocrinologist James Tanner, the scale measures the development level of three external sexual characteristics—genital development in boys, breast development in girls, and pubic and body hair distribution in both boys and girls—and provides five stages of development for each characteristic. Stage 1 marks the beginning of puberty for children and Stage 5 signals the attainment of adulthood. The further along in maturation kids are, the more likely they’ll be experiencing a delay in sleep onset and the later that delay may become. (If you haven’t seen your child streaking through the house lately, it’s likely that puberty has at least begun.) Another way to measure melatonin levels and pinpoint the timing of the sleep cycle is to collect hourly saliva samples from your teen between noon and midnight in a sleep doctor’s office. If your teen keeps a careful sleep log for one or two weeks, though, it should provide all the information that’s needed to figure out how late the sleep delay is and where the sleep-onset clock is set. |

Why do these brain changes occur? Why is melatonin secreted later? We don’t really know. But the brain is intricately complex, and the changes it experiences likely benefit the process of maturation in ways we have yet to appreciate. It’s also possible that evolution plays a role: Primitive cultures considered pubertal adolescents to be adults, and their ability to stay awake at night to stand watch may have made a valuable contribution to their societies.

For now we only know that in teens the timing of sleep is much later. We also know that the overwhelming majority of young people experience this Delayed Sleep Phase Syndrome, or DSPS, which puts them at odds with the world around them (especially their parents!). It also contributes to making them chronically drowsy and exhausted at times of the day that we think they should be at their peak.

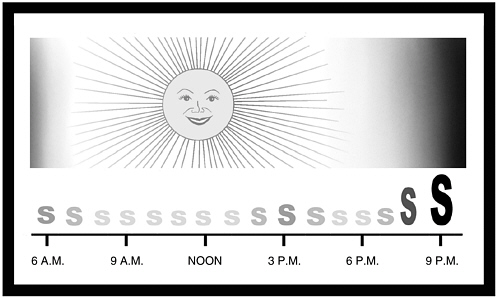

Process S and Process C

To truly understand the adolescent DSPS, you need to understand the biological factors behind it. Two processes—Process S, or the homeostatic sleep system, which refers to the buildup of sleepiness with increasing hours of wakefulness; and Process C, or the human circadian day-night timing system and clock-dependent alertness—are involved in the regulation of the timing of sleep, and both are disturbed in the DSPS. In simple terms, Process S drives the need for sleep and Process C controls the timing of sleeping and wakefulness. How alert or sleepy you are depends on the sum of the interaction of these two processes.

Process S is a pretty straightforward process: The longer you’re awake, the greater “sleep need” you accumulate. However, except for a dip in alertness between 2:00 and 5:00 in the afternoon, you don’t notice the need to sleep very much until bedtime. That’s because it’s opposed by powerful circadian clock-dependent alerting signals from a region of the hypothalamus called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (see below). By bedtime, however, the sleep debt is overwhelming and causes you to pull up the comforter for some much-needed ZZZZs.

But what sends our bodies into sleep mode? It’s still a bit of a mystery. However, many scientists follow one of two theories: Either a chemical is building up in the brain and when there’s enough of it sleep results or a chemical is being depleted in the brain and when it’s used up the sleep curtain falls. Whichever is the case, Process S works like a clock, ticking off the time until you get drowsy enough to fall

Building sleep debt as the day progresses.

Suppression of the feeling of building sleepiness during the day by Process C: clock-dependent alertness. Note the slight increase in sleepiness at “siesta” time in the later afternoon.

asleep and counting the hours of sleep necessary to restore energy and alertness.

The problem with Process S and teens, though, is that teens don’t get as sleepy as quickly as adults and younger kids do; the curve for how sleepy teens get actually slows down and teens don’t accumulate as many “sleepiness points” as their younger siblings or parents. So a 15-year-old going through puberty can be up for the same number of hours as a 10-year-old or a 40-year-old but not feel as sleepy. That makes feeling awake well into the wee hours much easier for teens, but they still need nine hours of sleep to discharge their sleepiness.

Superimposed on this pattern lies the workings of Process C, in which our internal body clock regulates all of our biological processes. Process C causes us to feel more alert at certain times of the day even if, according to Process S, we’ve been awake long enough to have gained a large number of sleepiness points.

Our internal body clock is actually centered in a pinhead-sized nucleus called the suprachiasmatic nucleus, or SCN, that is deep in the hypothalamic region of the brain and receives environmental information about daylight and darkness via the retina. When that information

Later onset of alertness and slower accumulation of sleep need in adolescence.

is relayed to the SCN by way of the retino-hypothalamic pathway, the hypothalamus establishes body process patterns in accordance with the day-night cycle. Those processes include brain wave activity, hormone production, cell regeneration—and sleeping and waking times.

In teens, however, Process C is set to a later clock time, enabling them, as we well know, to sleep late in the morning even though it’s light outside. While Process C causes most adults to experience robust alertness during the day and the strongest need for sleep between 2:00 a.m. and 4:00 a.m., teens’ sleep phase delay causes their strongest dip in alertness to be between 3:00 and 7:00 a.m. and can make that dip last until 9:00 or 10:00 a.m. if the teens are sleep deprived. If it’s hard

Contrast between the sleep-wake schedule of a prepubertal child and that of an adolescent. Specifically note the later onset of alertness, later dim light melatonin onset signaling the initiation of processes leading to sleep, and later sleep onset time for the teen.

to understand why it’s so incredibly difficult to wake a sleeping teen at 6:00 a.m., think how hard it would be if you had to get up for work at 3:00 a.m.—it’s pretty much equivalent.

For sleep to occur, the clock-dependent alertness that’s generated by Process C needs to be turned off by melatonin. For children and adults who go to bed at 10:00 p.m., melatonin secretion, or dim light melatonin onset, typically begins about six hours earlier, around 4:00 p.m. But in adolescents melatonin onset may not occur until hours later.

Still another problem is the length of the day. Children’s and adults’ body clocks follow a day that is approximately 24.3 hours long, but— you guessed it—the adolescent body clock beats to a different drum. Teens’ biological processes work to a slightly longer day, one that can

last up to 24.7 hours. Their longer day makes it even easier for them to sleep late in the morning, especially when they’re sleep deprived.

SNOOZE NEWS

The circadian rhythm your body follows not only regulates when you fall asleep and when you wake up but also influences how alert or tired you are, how long you sleep, and how well you sleep. The word “circadian” comes from the Latin word circa and literally means “around a day.”

All of this means trouble for teens. Because their day-night cycle doesn’t follow the typical 24-hour clock, they don’t make the day-night shift when everyone else does—their morning comes later and their day lasts longer. And because they typically need to follow the schedule adults adhere to, they feel out of whack and are always trying to cram a longer day into a 24-hour period—and suffering the consequences. Alterations of the three sleep-wake factors—the slower buildup of sleepiness during the day, the delayed influence of light, and the longer day—make our adolescents different and uncomfortably out of sync.

Teens’ sleep phase shift desynchronizes them from the 24-hour day that the circadian rhythm is entrained, or geared, to—in other words, it upsets the balance between teens’ timing for sleeping and waking and the timing of what’s going on in their environment. And as they progress through puberty and go to sleep later and later, becoming sleep deprived from having to get to school so early in the morning, they desynchronize even further and become true night owls. Without intervention and treatment to put teens back in sync, their circadian

Physiologic and social pressures resulting in a restricted total sleep time.

|

Another Teen Says … “I don’t like being a night owl. It makes it very hard for me to maintain a normal schedule and I feel like I miss so much—mornings, breakfast, a lot of daytime productivity, classes, relationships. Now that I’m working I’m missing out on the opportunity to make a good impression by showing up early—or even on time.” |

clocks get pushed out so late at night that they fail to put them to sleep at anything like a normal hour.

Catching Up—Or Staying Behind?

With their changing, out-of-sync brain chemistry, and suffering from the phase shift that results, is it any wonder that teenagers are often out of sorts and out of energy? On the one hand, their bodies are telling them to go to sleep at midnight or even later, and on the other hand society is telling them they have to get up early to go to school. The physiological demands of adolescence are daunting enough on their own—and starting earlier and earlier (girls, on average, now get their first period at the age of 11)—without the negative effects of sleep deprivation and the added demands that lack of sleep puts on the body.

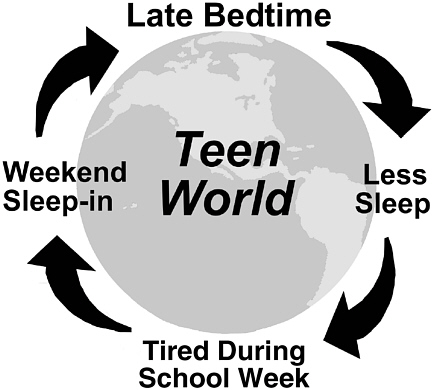

So what do most teens do to counter that feeling of total exhaustion and to help them make it through their school-, sports-, family-, and activity-filled weeks? Well, they sleep till noon on the weekends, of course, trying to catch up on as much sleep as they can beyond the five or six hours that is the norm on school nights.

But that’s not a solution. In fact, in the long run, catching up by sleeping late on the weekends actually causes more problems. If teens get up at noon on Sunday, they’ll need to accumulate sleepiness for 15 or 16 hours before they can go to sleep again—which means they may not be able to fall asleep until 4:00 a.m. on Monday! The late weekend wake-up time only reinforces the underlying sleep phase delay. It also makes it hard for teens to fall asleep at a reasonable time on Sunday night and causes them to be significantly sleep deprived come Monday morning. By sleeping late teens may feel better because they’ve paid

Adolescent vicious cycle of sleep deprivation and late sleep-ins on weekends perpetuating the delay in sleep phase.

back some of their sleep debt, but at the same time they’re perpetuating the desyncronization between their day-night cycle and their school schedule.

The NSF agrees that sleeping late on the weekends is not a solution to sleep problems. It reports that irregular sleep schedules, which include those with major differences in the time and duration of sleep between weekdays and the weekend, further contribute to a shift in sleep phase. Not only that, but irregular sleep patterns result in difficulty falling asleep or waking up and in poor sleep quality. These problems can produce teens who not only stay just as exhausted as ever but who suffer a whole raft of emotional, behavioral, physical, and health problems.

Can sleep-deprived kids ever really catch up? Without getting their circadian rhythm back on track, the answer is probably not. Think of it this way. Say, your daughter gets to bed around midnight on a routine

basis. She’s got to catch the 6:30 bus to get to school for the 7:20 start time, which means she drags herself into the shower at about 6:15. Most weekdays she barely gets six hours of sleep—which is at least three hours less than the nine-plus hours teens need to function optimally. So over the course of a school week, your daughter is deprived of 15 hours of all-important sleep.

Then, let’s say, she sleeps from 1:00 a.m. to noon on both Saturday and Sunday. Ah, you think, she’s catching up, she’s getting her much-needed nine hours on both days plus two extra hours. But we have to look at the big picture. Yes, she’s getting more sleep than she does on school nights, but since she needs nine hours, she’s only paying back two hours of sleep debt each night. Even after a great weekend of sleep, your daughter is still deprived of nearly 11 hours of the good stuff—and that’s after only one week of school!

Being so significantly sleep deprived causes problems. (Getting a bit less than nine hours a night on occasion may not have a major negative impact on your teen’s well-being, but chronic sleep restriction of less than eight hours a night has been proven to impair it.) What are those problems? Everything from being downright grouchy and more than a little unpleasant to health problems, including a higher risk for infections and obesity; emotional problems, such as increased anger and sadness; judgment problems, including the inability to think clearly; increased risk of injury; poorer sports performance; and an increased propensity to abuse alcohol and other drugs. In the following chapter I’ll go into depth on these and other problems related to sleep deprivation, and in Chapter 4 you’ll find an in-depth look at the newly discovered, critical link between learning and sleep. In both chapters you’ll learn how sleep deprivation is a major threat to your teen’s well-being.