4

The Rating Schedule

This chapter reviews the Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA’s) Schedule for Rating Disabilities (Rating Schedule) and makes recommendations for improving its effectiveness as the basis for compensating for service-connected disabilities. It is judged specifically for its ability to compensate for impairments in earning capacity and impacts on quality of life, as well as disability more generally. The processes for applying the Rating Schedule are addressed in Chapter 5. This chapter describes how the Rating Schedule came about and its substantive medical content, as well as how it is managed organizationally, including how revisions are made to it. The committee also reviews the currency of medical knowledge represented in the Rating Schedule and makes recommendations for improving the medical basis of the Rating Schedule and keeping it up to date.

The first part of this chapter describes the long and complex history and development of the Rating Schedule into the current century. It should be noted that, although the practice of providing pensions for veterans with disabilities began in the English colonies in North America, the first national pension law in the United States was adopted by the Continental Congress on August 26, 1776. A number of amendments, consolidations, and veterans acts followed, leading up to the current Rating Schedule used in the determination of eligibility for disability compensation.

The second part of this chapter delves into a detailed description of the Rating Schedule as it currently exists and discusses the numerous aspects of its maintenance and updating to serve the expanded purposes of veterans disability compensation recommended in Chapter 3.

HISTORY

There has never been any question but that it is the Government’s duty and responsibility to provide, and to provide generously, for those who, while or as a result of serving their country in time of war, suffered disease or injury which resulted in their being unable to support themselves—in other words, those with service-connected disability. It has been accepted that the Government should compensate them in accordance with their disability…. Criticism of Government’s actions in this area of veterans’ benefits has been as much that the compensation paid these beneficiaries has been too small as that it has been too large (President’s Commission, 1956b:65).

The English set a precedent for providing benefits to men disabled in the military service (President’s Commission, 1956b:5). Another precedent was set in 1636, when the Plymouth Colony enacted the first law in the English colonies in North America, which provided money to veterans who acquired disabilities as a result of battles with Pequot Indians (VA, 2007a). Other colonies followed this example. The Continental Congress passed the new country’s first pension law in 1776 to encourage enlistments and curtail desertions (VA, 2007a,b). Compensation for service-connected disability at “half pay for life or during disability” was provided “to every officer, soldier, or sailor losing a limb in any engagement or being so disabled in the service of the United States as to render him incapable of earning a livelihood,” and those partially disabled from getting a livelihood were promised proportionate relief (President’s Commission, 1956b:5). Because the Continental Congress lacked the authority or the money to make the pension payment, it was left to the individual states to make the payments. At most, only 3,000 Revolutionary War veterans drew any pension because the obligation was met differently by the individual states (VA, 2007a). The impact of the Revolutionary War was important because awarding the pensions to these veterans set a precedent for later wars. Another key development was the recognition of the political importance of the veterans, although no formal organization among veterans for political purposes would come about until later. The most important development “was the establishment of the idea that the Government owed it to the veterans to protect them against indigency in their old age and also owed a debt of gratitude to all veterans which should be paid in the form of pensions” (President’s Commission, 1956b:9).

Basic benefits for veterans remained unchanged for 35 years following the end of the Revolutionary War (President’s Commission, 1956b:7). The U.S. Constitution was ratified and the first federal pension legislation was

passed in1789. The payment of benefits to veterans was assumed by the first Congress, and the Continental Congress pension law was continued. In 1802, the Secretary of War requested the U.S. Attorney General to interpret military pension law:

… the connexion [sic] between the inflicting agent and consequent disability need not always be so direct and instantaneous. It will be enough if it be derivative, and the disability be plainly, though remotely, the incident and the result of the military profession … such are the changes and uncertainties of the military life … that the seeds of disease, which finally prostrate the constitution, may have been hidden as they were sown, and thus be in danger of not being recognized as first causes of disability in a meritorious claim.1

By 1808, the Bureau of Pensions under the Secretary of War administered all veterans programs. In 1811, the federal government authorized the first domiciliary and medical facility for veterans (VA, 2007a,b). The War of 1812 and the Mexican War, which intervened between the Revolutionary and the Civil Wars, did not reflect significant developments regarding the nature or scope of veterans benefits; compensation for service-connected disability was provided for veterans of these wars at their onset (President’s Commission, 1956b:10).Veterans and dependents of the War of 1812 were included through subsequent laws, and benefits to dependents and survivors were extended as well. By 1816, there were 2,200 pensioners, and in that year Congress raised allowances for all veterans with disabilities and granted half-pay pensions for five years (and later for a longer time period) to widows and orphans of soldiers of the War of 1812 to acknowledge the growing cost of living and a Treasury surplus (VA, 2007a,b).2

As a result of the surplus, President Monroe suggested in December 1817 that provision be made for the surviving Revolutionary War veterans; he anticipated that the cost would be minimal because there were so few of them remaining. Impassioned arguments urging this expression of gratitude of the country for these veterans prevailed although there was a lack of unanimity expressed by a minority in both houses of Congress as to the proper approach that should be taken to compensating them. For example, Senator William Smith, South Carolina, condemned the measure because he felt it was based on good feelings and sentiment, which he did not believe to be appropriate guides to a legislator. He pointed out that veterans of the War of 1812 would be the next to have as good a claim to such pensions, and

predicted that this measure’s precedent would be regretted later (President’s Commission, 1956b:7-8).3

The Revolutionary War Pension Act of 1818 (3 Stat. L., 410) transferred administration of pensions to the Secretary of War (under the War Department), replacing the service pension programs run by a few states. Veterans who had served at least nine months in the Continental Army and who were also “in reduced circumstances” received lifetime pensions at half-pay of the rank held during the Revolutionary War. It was anticipated that the program would be “brief” and “inexpensive,” an expression of gratitude and an act of charity for the benefit of indigent veterans who would otherwise be put in the humiliating position of having to search for evidence or produce surgeons’ certificates. According to this legislation, every person who had served in the war and was in need of assistance would receive a fixed pension for life, at a rate of $20 a month for officers and $8 a month for enlisted men. Prior to this time, pensions were granted only to veterans with disabilities (VA, 2007a). There was an immediate rush of applications and efforts to prove need where none existed, perhaps indicating a sense of entitlement regardless of need (President’s Commission, 1956b:8). From 1816 to 1820, the number of pensioners increased from 2,200 to 17,730 and the cost of pensions rose from $120,000 to $1.4 million (VA, 2007a).

The act was amended in 1820 because the original program was found to be “long, costly, and divisive.” The program was converted to a hybrid of pension and poor-law provisions, and all recipients were suspended from the rolls pending proof of poverty. Claimants ages 65 and older were allowed the maximum rate only for senility.

There were about 80,000 war veterans at the time of the 1861 Civil War. By the end of the war in 1865, 1.9 million Union forces veterans were added to the rolls.4 Disability payments based on rank and degree of disability were provided by the General Pension Act of 1862 (12 Stat. L., 566) (the General Law), and it “applied to the Civil War and to any or all future wars in which the United Sates might be engaged” (President’s Commission, 1956b:13). Some changes in detail were made, and more liberal benefit provisions for widows, children, and dependent relatives came about, but it continued the same provisions and philosophy:

The claimant must show that his disability was the result of his military service, or, if it did not arise until after his separation from service, he must show that it arose from causes which could be directly traced to injuries

received or diseases contracted while in the military service (President’s Commission, 1956b:14).

With this act, included for the first time, was compensation for diseases (e.g., tuberculosis) incurred while in service (VA, 2007a).

The rise in importance of veterans groups developed during the Civil War:

The Civil War was fought under conditions well calculated to impress upon veterans their political power and importance as a group. During the war there was continuous jockeying for political power. Each time an important election was held large numbers of soldiers were furloughed to come home and vote. Particularly was this true in the election of 1864. The importance placed upon the soldier vote in this election was impressed upon the Army and helped lay the groundwork for the later emergence of the Grand Army of the Republic as a potent political force. Since the Republicans were in power, their party became the one which made efforts to save the Union by defeating the rebels; the Democrats, because they were the opposition party, became largely identified with the Copperheads. Service in the Armed Forces also became extremely important politically for candidates for national office for many years after the war (President’s Commission, 1956b:11).

After the Civil War, veterans groups (e.g., the Grand Army of the Republic representing Union Veterans of the Civil War) organized to seek increased benefits (VA, 2007a):

… the post-Civil War period was the first one when veterans had been organized for the purpose of exerting political pressure in favor of higher benefits for veterans…. The Civil War group was the forerunner of a whole series of veterans’ organizations which have been formed along similar lines for the purpose of representing veterans with an organized voice (President’s Commission, 1956b:12).

In 1866, to address the needs of the large number of veterans with disabilities, Congress authorized the National Asylum for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, which in 1873 was called the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. The 1873 Consolidation Act revised pension legislation, basing payment on the degree of disability rather than on service rank (VA, 2007a). The act came about because the laws had become so complex and conflicting, leading to the need for codification (President’s Commission, 1956b:21).

The Arrears Act was passed in 1879, and it applied to claims filed prior to 1880. Its expense was unanticipated, and it generated an influx of applications. It was precipitated by the 1873 consolidation; payment of arrears of compensation to veterans or dependents of veterans who had not

applied for compensation until after the five years specified by the law had elapsed was at issue:

For the individual who had applied within 5 years, the compensation commenced at the death or discharge of the person on whose account the compensation was granted; for anyone who did not apply within 5 years, the compensation commenced with the filing of the last evidence necessary to complete the claim. It was contended that this discriminated unfairly against the person who tried to get along without compensation and on that account delayed the filing of his application (President’s Commission, 1956b:21).

Until 1890, Civil War pensions were granted only to servicemen discharged because of illness or disability as a result of military service. However, that year the scope of eligibility was substantially broadened, and pensions were provided to veterans incapable of manual labor. By 1893, the number of veterans receiving pensions increased from 489,000 to 996,000, while the expenditures for the program doubled. There were no new pension laws after the Spanish-American War (1898)5 or after the Philippine Insurrection (1899 to 1901) (VA, 2007a).

With the passage of the Sherwood Act of 1912, all veterans were awarded pensions, whereas in the 19th century, recipients had been limited by a similar law to veterans of the Revolutionary War. Under the Sherwood Act, veterans from the Mexican War and Union veterans of the Civil War could receive pensions automatically at age 62 even if they were not sick or disabled. The record shows that of the 429,354 Civil War veterans on pension rolls in 1914, 52,572 qualified on the basis of disability (VA, 2007a).

Military factors clearly led to developments in pension policies prior to World War I; however, the poor medical care and service received by soldiers in all wars prior to World War I may have been a more significant factor:

Disease became a part of the disability picture, killing more men and probably disabling more men than did the bullets of the enemy. These disabilities due to disease, however, were very difficult to establish service connection for, and brought about much of the demand for pensions, particularly following the Civil War and the Spanish-American War. Confused and incomplete records of all kinds gave rise to much difficulty in establishing the facts of service and the facts of medical records on the basis of which to establish service connection of disabilities.

During this entire period there were no general social welfare programs of any kind in existence for either the entire population or for special groups within the general population. The ruling thought pattern seems to have been that the individual should be responsible for providing for his own

welfare without aid from the Government or from any other organization. Aid given to individuals was provided by private charity. There was no protection against such hazards as losing one’s job because of disability, because of old age, or for any other reason. Veterans’ pensions, especially those for Civil War Veterans, provided a comprehensive plan of security for eligible veterans against the hazards resulting in loss of income or in death (President’s Commission, 1956b:24).

Prior to World War I, the War Risk Insurance Act of 1914 (40 Stat., 398–411) was passed to insure American ships and their cargoes. In 1917, after the war began, benefits legislation reflected readjustment and rehabilitation. It is estimated that 4.7 million Americans fought in this war, which left 116,000 dead and 204,000 wounded. The War Risk Insurance Act Amendments of 1917 were enacted to provide insurance against loss of life, personal injury, or capture by the enemy of personnel on board American merchant ships (VA, 2007b). Government-subsidized life insurance for veterans with an option for dependent death or disability coverage was provided. Under the act, a dependent’s pension in case of death or disability was approved, as well as a $60 discharge allowance at war’s end in recognition of service rendered.

Other provisions included the authority to establish courses for rehabilitation and vocational training for veterans with dismemberment, sight, hearing, and other permanent disabilities, with eligibility established retroactively to April 6, 1917, when the United States entered World War I. Veterans injured in service were retrained for new jobs.

An average earnings impairment disability rating schedule was introduced and, for the first time, service-connected “aggravation” of preexisting conditions applied (Gosoroski, 1997). Section 302 of the War Risk Insurance Act of October 6, 1917, provided the following:

A schedule of ratings of reductions in earning capacity from specific injuries or combinations of injuries of a permanent nature shall be adopted and applied by the bureau. Ratings may be as high as one hundred per centum. The ratings shall be based, as far as practicable, upon the average impairments of earning capacity resulting from such injuries in civil occupations and not upon the impairment in earning capacity in each individual case, so that there shall be no reduction in the rate of compensation for individual success in overcoming the handicap of permanent injury. The bureau shall from time to time readjust this schedule of ratings in accordance with actual experience (cited by Paul Ising, retired VA executive, in a written communication provided to the committee).

The Act of June 25, 1918, further amended the War Risk Insurance Act of 1914 (Ch. 104, part 10, 40 Stat. 609, 611). It stated that in determining disability entitlement individuals having active service in the military

“shall be held and taken to have been in sound condition when examined, accepted, and enrolled in service.”

The Vocational Rehabilitation Act of 1918 authorized the establishment of the Federal Board for Vocational Education, an independent agency. Any honorably discharged veteran of World War I was made eligible for vocational rehabilitation training; those unable to undertake gainful occupation were also eligible for a special maintenance allowance (VA, 2007b).

In 1921, during the administration of President Harding, a committee investigating the administration of the laws pertaining to veterans recommended that

… there should be created a Veterans’ Service Administration, an independent agency to which should be transferred the Bureau of War Risk Insurance, the Rehabilitation Division of the Federal Board for Vocational Education, and such part of the Public Health Service as was necessary in dealing with the beneficiaries of the Bureau of War Risk Insurance and the Rehabilitation Division (Secretary of the Treasury, 1921).

Further, the committee recommended that the Secretary of the Treasury be empowered to consolidate veterans benefits under the Bureau of War Risk Insurance except for hospital and medical care. These recommendations led to the passage of P.L. No. 47 (67th Cong.) in 1921, under which the administration of all laws pertaining to World War I veterans was concentrated (President’s Commission, 1956b:30). The Veterans Bureau was established and the first codified Schedule for Rating Disabilities was drafted that same year. In debate on July 20, 1921, Senator Walsh argued:

It is very apparent to me that this wave of tuberculosis and nervous and mental disease that has taken such a deadly hold and grip of late upon our ex-service men must have been contracted in the service. I feel, therefore, that we ought not continue this requirement of endless affidavits, necessarily involving long delay, in demonstrating the fact that their illness is of service origin. The delays resulting from this affidavit requirement have often resulted in men dying before they ever got their compensation.

The 1921 Rating Schedule amended the presumption of soundness to exclude defects, disorders, or infirmities recorded at the inception of active service. It also provided for presumption of service connection for tuberculosis and neuropsychiatric conditions,6 and for creation of local rating boards around the country instead of a single rating board in Washington, D.C. (VBA, 2005).

The World War Veterans’ Act of 1924 required a new Rating Schedule, which was created and placed into operation January 1, 1926. Known as the 1925 Rating Schedule, it had evaluation percentages in increments of 1 percent. On the positive side, unlike the 1945 Rating Schedule presently in effect, it did not require an increase of 10 percent for each upward adjustment. On the negative side, the scale required arbitrary discrimination to determine the difference between one or two percentage points. This schedule provided a disability rating based on assumptions about the skills and functions needed for specific occupations. For example, a veteran with a disability resulting from an ocular disorder would receive a higher disability evaluation if the individual worked as an accountant as opposed to a laborer with the same disability. Put differently, good eyesight was considered to be more important to a veteran who worked with written materials and numbers than to a veteran who performed manual tasks. This kind of determination provided the original rationale for including an occupational specialist on the rating board.

This act consolidated, codified, and liberalized the regulations and made significant changes in benefits; however, it was not definitive. It extended the presumption of service connection for tuberculosis and neuropsychiatric diseases to January 1, 1925, and added paralysis agitans, encephalitis lethargica, and amoebic dysentery to the presumptive list, which if they appeared before January 1, 1925, were presumed to be service connected (President’s Commission, 1956b:33).

The next major liberalization occurred in 1926, with the establishment of a statutory tuberculosis award of not less than $50 a month for any ex-service person shown to have had a tuberculous disease of a compensable degree who had reached complete arrest of the disease; 43,719 veterans were receiving this benefit by June 30, 1932 (President’s Commission, 1956b:33). In 1930, P.L. No. 522 (71st Cong.) was passed to grant aid in the form of a pension to needy, disabled World War I veterans with other than service-connected disabilities, with payments ranging from $12 to $40 a month depending on the degree of disability; within a little over two years, 440,954 veterans were receiving pensions. This law was passed when the United States was going into the Depression and no Treasury surplus was available to pay for it (President’s Commission, 1956b:33–34).

The Economy Act of March 30, 1933 (P.L. No. 2, 73rd Cong.), which eliminated payments to all veterans without service-connected disabilities except those who were totally disabled and could meet an income test (President’s Commission, 1956b:39), authorized the next version of the Rating Schedule. The 1933 Rating Schedule eliminated evaluations in increments of 1 percent and substituted multiples of 10 percent. It also eliminated the

difference between temporary and permanent evaluations.7 Additionally, it provided for the bilateral anatomical loss (e.g., two eyes, two feet, two hands, or any combination thereof) factor as it is used today. Further, the 1933 Rating Schedule eliminated the occupational variance and substituted the concept of average impairment in civilian occupational earnings capacity resulting from certain diseases and injuries. Historically, the War Risk Insurance Act of 1917 had called for implementing a Rating Schedule to be based on “the average impairment in earning capacity” caused by a disability. Average impairment was to be based on average loss of earnings for all occupations performing manual labor. Legislation in 1924 provided that the Rating Schedule should still be based on the concept of average impairment with the recognition of the effects of the disability on the preservice occupation of the veteran. However, this 1933 legislation led to reverting back to “average impairment of earnings capacity” (Economic Systems Inc., 2004b).

The advent of the Economy Act brought Executive orders into the system of veterans benefits:

The Economy Act of 1933 cancelled all previously established benefits for veterans of wars since 1898 and substituted instead a system of veterans’ benefits established by Executive order. The new system drastically curtailed all benefits, reduced pension payments to those with total disability, sharply reduced the payments going to those with service-connected disabilities, removed many cases for the rolls altogether, and cut down sharply on the benefits. Some liberalizations were made in the Executive orders during the following 2-year period, and by the end of 2 years, former laws, with the exception of that one granting disability pensions to veterans with non-service-connected disabilities, were substantially reenacted. Pensions continued to be limited to those suffering from total disability (President’s Commission, 1956b:45).

The 1945 Rating Schedule became effective April 1, 1946, and formed the basis for the current schedule. This schedule raised the percentages of disability for some impairments and lowered them for others. It also provided for a review of all ratings under the 1925 and 1933 Rating Schedules. Under the 1945 Rating Schedule, a higher evaluation was assigned when possible, but “protection” of a higher rating under the prior Rating Schedule was not provided. (Protection in this context means that a disability rating would not be reduced solely on the basis of the application of the new Rating Schedule. However, a rating could be reduced if

medical evidence establishes that the disability being evaluated has actually improved.) In the 1925 and 1933 Rating Schedules, if the application of the new schedule resulted in a reduction in the rating, the disability rating under the prior Rating Schedule was retained in a protected status. Thus, the assigned rating could only increase. Under the 1945 Rating Schedule, however, the assigned rating could decrease.

According to a July 1954 General Accounting Office (GAO) report:

The disability ratings provided in the rating schedules are not based on an actual determination of the effect of the various disabilities on the average earning capacity of individuals in civil occupations. The Chairman of the VA Rating Schedule Board, in a statement dated January 21, 1952, regarding various aspects of the disability rating problems … indicated that the 1945 schedule is an outgrowth of other rating schedules which had been in use at various times from 1921 to April 1, 1946. He stated that the disability ratings provided in the 1921 schedule were not calculated on statistical or economic data regarding the average reduction in earning capacities from any disability because such data were not available, and that they undoubtedly represented the opinions of the physicians who had developed the schedules as to the effect of the various disabilities upon the earning capacity of the average man. He also stated that the disability percentage ratings provided in the 1945 schedule are based on very little calculations but that they represent the consensus of informed opinion of experienced rating personnel, for the most part physicians, and reflect many compromises of their views (as cited in President’s Commission, 1956a:33).

Currently, VA uses the 1945 Rating Schedule and its medical criteria with some revisions to evaluate veterans for disability compensation.

THE CURRENT RATING SCHEDULE

Body Systems and Rating Disability

The current Rating Schedule assigns a percentage of disability, called a rating, based mostly on the severity of the veteran’s medical impairment or diagnosis. The underlying assumption of this system of rating is that degree of disability is the equivalent or reasonably similar to percentage of impairment. The differences between impairment and disability, and the need to broaden the rating system to take account of dimensions of disability beyond impairment, were discussed in Chapter 3.

As discussed in Chapter 3, although the purpose of the current Rating Schedule is to determine the extent to which impairment reduces earning capacity (work disability), the operational basis for these ratings is an evaluation of the severity of impairments resulting from the service-

connected injury or disease. Impairments or diagnoses in 14 body systems are delineated, as follows:

-

musculoskeletal

-

organs of special sense (vision and hearing)

-

infectious diseases, immune disorders, and nutritional deficiencies

-

respiratory

-

cardiovascular

-

digestive

-

genitourinary

-

gynecological conditions and disorders of the breast

-

hemic and lymphatic

-

skin

-

endocrine

-

neurological conditions and convulsive disorders

-

mental disorders

-

dental and oral conditions

The assigned percentages are in increments of 10 in a scale of 0 to 100. (Many service-connected conditions have relatively minor consequences and are rated zero.) When the disability is judged to be service connected and a compensable evaluation (at least 10 percent) is assigned, the veteran is entitled to receive monthly monetary benefits. Currently, the benefits range from $115 a month for a 10 percent rating to $2,471 a month for 100 percent or total disability rating for a single veteran. (Depending on the rating level, a veteran may be eligible for additional benefits, which are discussed in Chapter 6.)

The Rating Schedule contains about 700 diagnostic codes. If the veteran has a condition that is not listed in the Rating Schedule, the rater uses an analogous condition listed in the Rating Schedule to evaluate it.

The medical evidence must support both the diagnosis and the percentage assigned for the condition. Following the spirit of the law as reflected in the grateful nation principle, when the rater assigns a disability rating higher than one evaluation, but not sufficiently high to qualify for the next higher evaluation, the higher evaluation must be assigned as a matter of policy, backed by regulation.

The Rating Schedule also includes regulations and provides guidance pertaining to such topics as the

-

essentials of evaluative rating (assigning evaluation percentages);

-

interpretation of examination reports;

-

resolution of reasonable doubt;

-

evaluation of evidence;

-

analogous ratings;

-

attitude of rating officers;

-

use of diagnostic code numbers; and

-

assignment of a zero-percent rating.

Status of Rating Schedule Updates

The rating schedule was originated and designed hopefully on a scientific basis; and was to be revised and readjusted in accordance with actual experience. This “experience” has materialized, and the schedule of ratings has undergone several revisions, but the question or questions still remain—Whose actual experience? What kind of actual experience? When should this actual experience dictate a revision? Who was to designate the time of revisions, after actual experience dictated? Or, does actual experience dictate any revision of the veterans schedule for rating disabilities? … What are the criticisms of the current schedule? Is it outmoded? Is it in accord with the accepted medical principles and standard nomenclature? Are the ratings for the various disabilities equitable (President’s Commission, 1956c:155)?

The Rating Schedule has been updated unevenly over the years since this 1956 observation made by the Bradley Commission, which was published 11 years after the last revision had been made and after the addition of nine amendments by extensions. At that time, medical specialists were asked to review the Rating Schedule and respond to the following questions:

-

(K) Are the disability ratings in accord with present-day accepted medical principles?

-

(L) Is the disease nomenclature in accord with present-day medical standards?

-

(M) Do the medical criteria reflect accurately the residuals of the injury or disease for different percentage ratings?

-

(N) Is it medically feasible to assign graduations (sic) within an accuracy of 10 percent, when determining the percentage of bodily and mental impairment? If not, what scale of graduations do you regard as feasible?

-

(O) In your opinion, do the ratings fairly represent the average impairment of earning capacity resulting from the various degrees of severity of physical impairment?

-

(P) Do the disabilities at 10 percent and 20 percent constitute a material impairment of earning capacity?

-

(Q) Do you know of any medical data which can be used to set

-

percentage ratings to represent the average impairment in earning capacity resulting from various diseases or injuries and their residual conditions for civil occupations (President’s Commission, 1956c:156)?

Concerns expressed in response to the above questions, which are useful to the reader and illustrative of some of the same issues discussed in this report regarding the current Rating Schedule, are summarized in the Bradley Commission report:

-

(K—accepted medical principles) “… a considerable number of respondents, who were of the majority [favorable] opinion, agreed with the minority that numerous disability ratings and items in the schedule need revision in the light of changes in modern treatment, both surgical and medical, as disability ratings are changed when residuals of injuries and diseases are improved by operations, prostheses, and other mechanical aids, and particularly in the light of the new dug and surgical treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis. A large number of disability ratings do not properly take into account recent advances in medical rehabilitation, improved prostheses, reconstructive orthopedic surgery, and improved plastic surgery procedures” (p. 161).

-

(L—nomenclature) “… some of the majority took exception to the outmoded terminology in the psychiatric section of the schedule. This viewpoint was taken by all of the respondents practicing psychiatry. Standard nomenclature of diseases should be required for the physical disability processing and evaluation of the serviceman while in the service and after he becomes a veteran beneficiary. There is confusion of disease nomenclature between the agencies which have to use the schedule for rating disabilities in their physical disability processing and evaluation” (p. 165).

-

(M—residuals of the injury or disease) “… it appears that the majority opinions are that medical criteria accurately reflect the residuals of the injury or disease … with exceptions…. The minority opinion maintained … that the criteria did not … the majority and minority did agree that a revision of the criteria was required and that the medical criteria should be modernized and more clearly correlated to percentages, disability, and average impairment in earning capacity. The criteria for tuberculosis were singled out, as an example, as requiring revision” (p. 171).

-

(N—medical basis and percentages) “Although there was a slight majority of the respondents who believed that it is not medically feasible to assign gradations within an accuracy of 10 percent when determining the percentage of bodily and mental impairment, this majority were divided in their recommendations as to what scale of gradations they regarded as feasible. Still, a sizable minority were definite and clear in their opinion, that it is medically feasible…. Both the majority and the minority recognized

-

the fact that any scale adopted was an arbitrary scale. It is not medically feasible … in any patient with tuberculosis—according to the 8 medical respondents practicing this medical specialty. One tuberculosis specialist suggested the scale of ‘slight, moderate, severe, and total disability’” (p. 176).

-

(O—average impairment in earning capacity) “Some respondents believe, and others do not, that the ratings do or do not represent the average impairment of earning capacity resulting from the various degrees of severity of physical impairment. Lower ratings do not fairly represent the average impairment in earning capacity … particularly those ratings below 30 percent” (p. 180).

-

(P—disabilities rated at 10 percent and 20 percent) “Most of the medical specialists who responded to the question, two-thirds, said that the disabilities rated 10 and 20 percent did not constitute a material impairment of earning capacity” (p. 184).

-

(Q—known medical data) “Two-thirds of the respondents commented that they did not know of any medical data which could be used to set percentage ratings to represent the average impairment in earning capacity resulting from various disease or injuries and their residual conditions for civil occupations … of the group of respondents who state they knew of medical data … some made reference to certain medical publications; some made references to commercial insurance companies; State industrial commissions; and other State compensation commissions; other respondents in this group referred to miscellaneous sources” (p. 189).

The most recent revisions for body systems or sections within body systems went into effect between 1994 and 2002. In addition, one revision has been pending since 1999, one is under review, and two were withdrawn in 2004 (see Tables 4-1 and 4-2). Although the codes within a single body system classification may appear to have been revised as a whole by the issuance of an overarching Federal Register item, some of the contents of the sections (e.g., descriptive material, guidance) or specific diagnostic codes have been updated at different times over the years, while others have not been revised since the 1940s or 1950s (e.g., musculoskeletal body system). (See Appendix Table 4-1 for more detailed information about the changes that have occurred, including those in the descriptive text that accompany the diagnostic codes, which revise the criteria for assigning rating levels.) The orthopedic components of the musculoskeletal system and the neurological system have undergone the fewest revisions (see Table 4-1). This is yet another obstacle to providing a valid disability rating for veterans.

TABLE 4-1 Revisions of Diagnostic Codes, by Body System, Since 1945

|

Body System |

Number of Current Codesa |

Number and Percent of Codes Not Revised Since 1945b |

Number and Percent of Codes Revised, 1945 Through 1989 |

Number and Percent of Codes Revised Since 1990 |

|

Musculoskeletal: Orthopedic |

162 |

105 (64.8%) |

54 (33.3%) |

3 (1.9%) |

|

Musculoskeletal: Muscle injuries |

29 |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

29 (100.0%) |

|

Organs of Special Sense: Vision |

60 |

29 (48.3%) |

31 (51.7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

Organs of Special Sense: Hearing |

26 |

1 (3.8%) |

1 (3.8%) |

24 (92.3%) |

|

Infectious Diseases, Immune Disorders, and Nutritional Deficiencies |

22 |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

22 (100.0%) |

|

Respiratory |

82 |

0 (0.0%) |

9 (11.0%) |

73 (89.0%) |

|

Cardiovascular |

36 |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

36 (100.0%) |

|

Digestive |

52 |

20 (38.5%) |

24 (46.2%) |

8 (15.4%) |

|

Genitourinary |

42 |

12 (28.6%) |

3 (7.1%) |

27 (64.3%) |

|

Gynecological Conditions and Disorders of the Breast |

19 |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

19 (100.0%) |

|

Hemic and Lymphatic |

16 |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

16 (100.0%) |

|

Skin |

31 |

1 (3.2%) |

0 (0.0%) |

30 (96.8%) |

|

Endocrine |

19 |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

19 (100.0%) |

|

Neurological Conditions and Convulsive Disorders |

119 |

105 (88.2%) |

13 (10.9%) |

1 (0.8%) |

|

Mental Disorders |

67 |

0 (0.0%) |

8 (11.9%) |

59 (88.1%) |

|

Dental and Oral |

16 |

8 (50.0%) |

1 (6.3%) |

7 (43.8%) |

|

Total |

798 |

281 (35.2%) |

144 (18.0%) |

373 (46.7%) |

|

aThis table does not include the number of diagnostic codes that have been dropped, or added and subsequently dropped, since 1945, although this number would provide additional information on how much each body system has been revised since the Schedule for Rating Disabilities was issued in 1945. It also does not include analogous codes, although substantial increase in use of an analogous code in a body system might indicate a new code is needed. bIn other words, these codes were in the original 1945 Schedule for Rating Disabilities. |

||||

TABLE 4-2 Dates of Rating Schedule Changes in the 14 Body Systems

|

Body System |

Proposed |

Final |

Effective Date |

|

Genitourinary |

12/02/91 |

01/18/94 |

02/17/94 |

|

Dental and oral conditions |

01/19/93 |

01/18/94 |

02/17/94 |

|

Gynecological conditions and disorders of the breast |

03/26/92 |

04/21/95 |

05/22/95 |

|

Hemic and lymphatic |

04/30/93 |

09/22/95 |

10/23/95 |

|

Endocrine |

01/22/93 |

05/07/96 |

06/06/96 |

|

Infectious diseases, immune disorders, and nutritional deficiencies |

04/30/93 |

07/31/96 |

08/30/96 |

|

Respiratory |

01/19/93 |

09/05/96 |

10/07/96 |

|

Mental disorders |

10/26/95 |

10/08/96 |

11/07/96 |

|

Musculoskeletal: Muscles |

06/16/93 |

06/03/97 |

07/03/97 |

|

Cardiovascular |

01/19/93 |

12/11/97 |

01/12/98 |

|

Organs of special sense: Hearing |

04/12/94 |

05/11/99 |

06/10/99 |

|

Skin |

01/19/93 |

07/31/02 |

08/30/02 |

|

Digestive: Gastrointestinal |

08/07/00 |

(withdrawn in 2004) |

|

|

Musculoskeletal: Orthopedic |

02/11/03 |

(withdrawn in 2004) |

|

|

Organs of special sense: Vision |

05/11/99 |

|

|

|

Neurological conditions and convulsive disorders |

(under review) |

|

|

|

Digestive |

(under review) |

|

|

Updating Process

In 2002, the General Accounting Office (now known as the Government Accountability Office) pointed out that the procedures for revising the Rating Schedule contributed to the obsolete medical knowledge found in significant portions of the schedule. Currently, all proposed changes must be reviewed by VA’s legal counsel, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the VA Office of Congressional and Legislative Affairs, the VA Office of Inspector General, and the Office of Management and Budget. Further, the number of staff assigned to coordinate the updates and train the raters is not sufficient for the complex task: one staff person is assigned less than half-time to coordinate such efforts. GAO found that “VA does not have a well-defined plan to conduct the next round of medical updates” (GAO, 2002).

In 1989, to address some of the existing shortcomings with the rating system, VA hired a contractor to convene practicing physicians, organized by teams according to specific body systems, to review and update criteria for several of the body systems. The physicians were asked to propose changes in the Rating System that were consistent with modern medical practice and phrased in language that rating personnel could easily interpret. VA in-house staff reviewed the teams’ results, made necessary adjustments, and forwarded that information to various VA offices for review. The proposed changes were published in the Federal Register for comments and final rules were issued. As of March 2002, VA had finalized the criteria for 11 of 14 body systems (GAO, 2002).

In general, VA publishes an Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM) in the Federal Register prior to issuance of a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) for each body system revision, or for revision of a specific diagnostic code or explanatory note in a body system, to allow the public preliminary commentary on revisions VA is planning to propose. There are comment periods for both the ANPRM and the NPRM (generally 30 or 60 days). These notices explain in detail the reasons why revisions are deemed necessary and the specific revisions being proposed. The public comments and other pertinent information received are recorded and considered in light of their medical and regulatory appropriateness. The NPRM item contains agency responses indicating whether or not and why in each case the comments made in response to the ANPRM were used as part of the revisions. The new rules go into effect shortly after the Final Rule is published in the Federal Register. The Final Rule document contains the agency’s responses to commentators’ suggestions regarding the NPRM.

Revising the Rating Schedule has not been based on systematic studies of the reliability or validity of the rating criteria for the various conditions. Few such studies have been done. In 1983, VA had the regional offices (then numbering 56) rate 16 sample claims with 26 claimed disabilities.

The evaluation concluded that it was possible for raters to assign different ratings to the same condition because of the lack of precision of some rating criteria, inadequate medical records and reports, and reluctance of raters to ask for additional or clarifying information because of time pressures (VA, 2005). In 2005, the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) initiated a study of the consistency of decisions on three conditions: hearing loss, posttraumatic stress disorder, and knee conditions. VBA had 10 subject matter experts review 1,750 regional office decisions and planned to follow up with additional studies of particular conditions and review areas identified with consistency problems every two to three years (FY05 PAR:221). The results were briefed to VA leaders but not made public. Also in 2005, VA contracted with the Institute of Defense Analyses to determine the major factors contributing to state and regional variation in disability compensation claims, ratings, and payments. VA expects the results to help in identifying corrective actions to increase consistency (IDA, 2007).

Evaluation of the Medical Knowledge in the Current Rating Schedule

The Rating Schedule contains a number of obsolete diagnostic categories, terms, tests, and procedures, and does not recognize many currently accepted diagnostic categories. Some examples of these are provided below. In other cases, the diagnostic categories are current but do not specify appropriate procedures to measure disability for the conditions.

Examples of Conditions in Need of Updating

Craniocerebral Trauma As an example of a condition that needs to be based on more current medical knowledge, the criteria for rating severity of craniocerebral trauma are not adequate because the description is out of date and does not provide guidance for the rating of multiple neurological disorders associated with craniocerebral trauma. The chronic effects of craniocerebral trauma include cerebrospinal fistula, pneumocephalus, carotid-cavernous fistula, vascular injury with thrombosis (although hemiplegia, seizures, and cranial nerve paralyses can be coded), infections, chronic headache, new onset migraine headaches, visual disorders, sleep disturbances, and (rarely) movement disorders. These criteria should be differentiated conceptually; they need to be updated to coincide with current knowledge and medical practice and should include not only more specific problems, such as acute and chronic sequelae, but also focal abnormalities from brain injury and symptomatic response to medication.

Neurodegenerative and Neurological Disorders As another example, the criteria for rating severity of neurodegenerative disorders are inadequate,

principally because most of the disorders currently considered to be neurodegenerative have not been included. Moreover, among the four that are listed in the Rating Schedule, only one (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) is currently considered to be neurodegenerative. Among the three others, both multiple sclerosis and myasthenia gravis are now classified as autoimmune, and syringomyelia is usually a developmental abnormality, often associated with the Chiari type I or type II malformation. In present practice, the neurodegenerative diseases are defined as disorders characterized by the progressive loss of neurons in focal, multifocal, or more widespread parts of the nervous system. The diseases commonly considered neurodegenerative include Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, multiple system atrophy, frontotemporal dementia, corticobasal degeneration, progressive supranuclear palsy, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Similar concerns exist regarding neurological conditions such as spinal cord injury (SCI). There are no clear criteria by which to evaluate neurological impairment and functional limitations related to SCI in the current Rating Schedule. Information used is based on cranial nerve impairments and very outdated, suggesting the need for adopting a more widely known classification system such as the one used by the American Spinal Injury Association (known as the ASIA Classification System for Neurological Disorders).

Posttraumatic Arthritis An additional example of inappropriate medical knowledge used in the current Rating Schedule is that of posttraumatic arthritis. The existing criteria for determining disability in posttraumatic arthritis depend on anatomical findings and the assessment of working movement, a term that is both archaic and imprecise. Specifically included are X-ray evidence of past trauma and loss of range of motion. This does not use the most commonly used imaging techniques, such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which provide significantly more anatomical specificity than X-ray films and are most frequently used in clinical settings in which trauma is assessed. Using imaging techniques to assess disability assumes a strong correlation between anatomy or range of motion loss and functional ability. This relationship is often not linear. Hence, these measures are inadequate in determining disability. However, the musculoskeletal guidelines provide detailed information on the range of factors that need to be considered. They include an opportunity to record pain or fatigue during repetitive motion, which are needed in this type of assessment.

Mental Disorders Since the ratings for mental disorders were last revised in 1996, VA has used a single rating formula to evaluate all mental conditions. Each rating level is based on a mix of symptoms that is not appropriately applicable to any particular mental disorder but reflects psychopathology

more broadly. When evaluating claims for mental disorders, raters (or the Board of Veterans Appeals) may request a Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score.

The GAF is used to assess functioning on Axis V of the multiaxial assessment system within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (APA, 1994). The GAF, derived from the Global Assessment Scale (Endicott et al., 1976), assesses psychological functioning (i.e., severity of symptomatology) and social and occupational functioning together on a single 100-point scale. This combined assessment approach was criticized for producing confusing and sometimes uninterpretable ratings by the multiaxial workgroup that design this portion of the DSM-IV (Goldman et al., 1992). The authors proposed separating the GAF into two separate scales (Goldman et al., 1992), and the resulting Social and Occupational Assessment Scale (SOFAS) was introduced in the appendix to DSM-IV (APA, 1994).

In addition to these limitations, GAF scores have not been shown to be reliable without systematic training of evaluating psychiatrists or psychologists: “Evidence suggests that without training, some raters may base their ratings on average symptom occurrence or functionality over time, while others will rate the most recent episode or lowest level of these two components. In disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), where symptom severity and functionality can fluctuate, these two approaches will yield very different GAF scores” (VA, 2002). There are also different interpretations of mild, moderate, and severe in assigning levels of severity. The GAF also measures both functional impairment and disability (APA, 2002). Therefore, “two patients with severe delusions may function at completely different levels but will still receive the same GAF score of 20 because of the symptoms” (APA, 2002:212). Because of such problems with validity and reliability, the American Psychiatric Association might drop or greatly revise the GAF in DSM-V (Narrow, 2006).

Since the Social Security Administration (SSA) revised its mental impairment standards in the early 1980s, a single rating scale has been used to assess work-related functional limitations. The Psychiatric Review Technique Form (PRTF) assesses functional limitations on four dimensions (activities of daily living; social interaction; concentration, persistence, and pace; and adaptive functioning or decompensation) using an ordinal scale (none, mild, moderate, marked, and extreme) or a frequency count. The PRTF has been assessed and found to be reliable and also to measure functional loss related to work disability (Pincus et al., 1991).

Other Examples The classification of epilepsy is totally out of date and should be replaced with the current international classification of the epilepsies. The distinction between neuritis and neuralgia is no longer in

keeping with current practice or knowledge of neuropathological changes in peripheral nerves. Examiners cannot reasonably be expected to provide information needed to apply the criteria, as the criteria are conceptually inadequate, out of date, and incomplete.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The first order of business should be to ensure that the Rating Schedule is up to date medically. Up to date medically means that

-

the diagnostic categories reflect the classification of injuries and diseases currently used in health care, so that the appropriate condition in the Rating Schedule can be more easily identified and confirmed using the medical evidence;

-

the criteria for successively higher rating levels reflect increasing degrees of anatomic and functional loss of body structures and systems (i.e., impairment), so that the greater the extent of loss, the greater the amount of compensation; and

-

current standards of practice in assessment of impairment are followed and appropriate severity scales or staging protocols are used in evaluating the veteran and applying the rating criteria.

Making the Rating Schedule medically current and keeping it up to date is addressed in the first recommendation, below.

The second order of business should be to see if and how measures of a veteran’s ability to function in everyday life could be integrated with or be used to adjust the impairment criteria. The third area that needs addressing is the assessment of disability and rehabilitation needs. It should be possible to establish a more effective process for coordinating VA benefits for veterans to maximize their capacity to function by developing and implementing an initial assessment process for all VBA programs. Would it be possible to base compensation partly on this assessment of disability, if it is more severe than the degree of impairment? Fourth, an effort should be made to determine if it would be possible to measure health-related quality of life and develop a way to compensate for its loss, if it turns out that the criteria in the Rating Schedule do not predict loss of quality of life. These issues are addressed in the recommendations below, along with the need to collect information on the economic aspects of disability and compensation.

Updating the Medical Aspects of the Rating Schedule

The Rating Schedule mostly assesses the medical severity of service-related injuries or diseases rather than the impact of the injuries or dis-

eases on the veteran’s life and work, although there is an assumption that degree of impairment and its social and economic consequences are roughly related, on average. Given the importance of impairment rating in the veterans disability compensation program, it is critical that the categories and criteria in the Rating Schedule are based on current medical knowledge and practice.

We began the study with a careful review of a number of the medical conditions included in the current Rating Schedule and were very concerned by what we found. In many cases, the medical knowledge used in the Rating Schedule is inadequate, often because the information is obsolete or there has been inadequate integration of current and accepted diagnostic procedures. In some instances, the nomenclature used for some of the ratings is obsolete, many modern diagnoses are not included, and even when symptoms (e.g., pain, fatigue) are mentioned, they are not included in a systematic fashion as possible contributors to the rating. In some instances, the percentages recommended do not reflect the level of severity of specific conditions the committee reviewed. For example, the assignment of 10 percent disability for symptoms of dizziness and shortness of breath associated with exercise of more than 7 and less than 10 metabolic equivalents of task (equivalent to jogging 3 miles in 30 minutes, something most Americans cannot do) is a reasonable assessment of disability. It may be an underestimate of the functional impact of the cardiac condition for certain specific vocational activities. For example, any dizziness would ground a pilot or a courier on bicycle, and they would be more than 10 percent disabled. This creates a situation in which the Rating Schedule may correctly rate the condition, and it is medically agreed that it has properly scaled the impairment, but the rating has not properly reflected the disability.

In exceptional cases, when the Rating Schedule does not adequately evaluate the condition in the opinion of the rater, the case can be referred to the director of the Compensation and Pension (C&P) Service for special consideration of a higher percentage, but this is not a frequent occurrence.

The Rating Schedule should be revised to remove ambiguous criteria and obsolete conditions and language, reflect current medical practice, and include medical advances in diagnosis and classification of new conditions. For a number of reasons, however, as indicated above, updates have been made slowly and relatively randomly, and the Rating Schedule remains outdated in both its organization and the current body system content, thereby hindering raters from providing accurate assessments of veterans’ disabilities.

The body system structure of the Rating Schedule is not necessarily based on current knowledge of relationships among conditions and comorbidities (e.g., autoimmune disorders, neurodegenerative diseases). Some related conditions are scattered throughout the body systems, such

as diabetes, a multisystem disease, and malignancies, should they become metastatic. We now understand that a common process underlies them wherever they occur.

The committee considers it important for VA to be as up to date as possible in current medical approaches to diagnosis and terminology as pertains to the Rating Schedule in order to serve veterans with disabilities more effectively and help them integrate or reintegrate into a productive and meaningful civilian life. VA should undertake a comprehensive revision of the Rating Schedule now and make it a formal process to revise the schedule every 10 years thereafter. One possible approach would involve the revision of several body systems each year on a staggered basis.

Recommendation 4-1. VA should immediately update the current Rating Schedule, beginning with those body systems that have gone the longest without a comprehensive update, and devise a system for keeping it up to date. VA should reestablish a disability advisory committee to advise on changes in the Rating Schedule.

The disability advisory committee should be appointed by and report to the head of VBA, although it might be staffed by the C&P Service. Its members should be experts in medical care, disability evaluation, functional and vocational assessment, and rehabilitation, and include representatives of the health policy, disability law, and veteran communities. The committee would meet several times a year to review developments in medicine and rehabilitation and consider the implications for the Rating Schedule. The committee could also advise on research needs and plans related to measurement of veterans’ disability and quality of life.

To make Recommendation 4-1 feasible, VA will also need to increase its staff capacity to update and revise the Rating Schedule. As an example, SSA’s disability program has an Office of Medical Policy with six doctors, representing a range of fields, and several times that number of analysts for the revision process. SSA is guided by the same Administrative Procedures Act in revising regulations, including the publication of ANPRMs, NPRMs, and Final Rules in the Federal Register. In the SSA process, however, health-care professionals are more systematically and extensively involved by serving as in-house medical experts. SSA also gathers feedback on relevant medical issues from state officials who help the agency make disability decisions. In addition, SSA uses its in-house expertise to keep current with advances in medicine and identify aspects of the criteria that need to be revised (GAO, 2002). In its informal notice and comment period, after the issuance of an ANPRM, SSA hosts at least one outreach conference, which includes invited medical experts, advocates, and patients. SSA staff review the input from the outreach conferences and uses this input to inform the

development of the NPRM. In contrast, VBA has one physician who works with staff in a unit responsible for all C&P regulations.

The Uses of the Rating Schedule

The Rating Schedule should be based on the best current medical evidence, which was the topic examined in the previous portions of this chapter. The Rating Schedule should also be designed to serve the purposes of the veterans disability compensation program, which is the topic examined in the balance of the chapter. Those purposes were identified in Chapter 3, namely to provide compensation for the impact of service-connected injuries and diseases on (1) work disability (loss of earning capacity), (2) the degree of nonwork disability incurred (loss of ability to engage in usual life activities other than work), and (3) loss in the quality of life (QOL).

The discussion of how the Rating Schedule serves the purposes of the veterans disability compensation program is based in part on the paper in Appendix C of this report, “The Relationship Between Impairments and Earnings Losses in Multicondition Studies” (Relationship Study). The Relationship Study examines the relationship of ratings to earned income in the workers’ compensation programs in Wisconsin and California and the Economic Validation of the Rating Schedule Study.

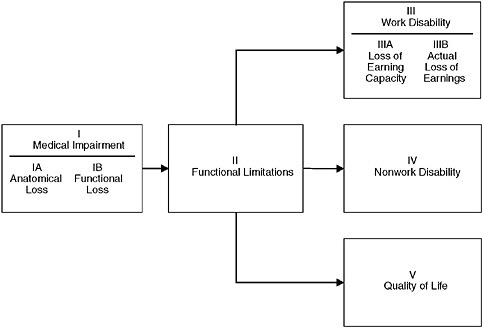

One of the important contributions of the Relationship Study is the distinction between the purposes of the disability benefits and the operational basis for the benefits. That distinction can be illustrated by the entries in Figure 4-1.8

The concepts in Figure 4-1 correspond to the operational measures actually or potentially used to determine the amount of cash benefits provided by the workers’ compensation and veterans disability programs, as well as the outcome measures used in research on disability and health-care programs. (The terms are defined in greater detail in Appendix C.)

IA. Medical impairment: anatomical loss refers to impairment ratings that are based on anatomical loss, such as amputation of the leg.

IB. Medical impairment: functional loss refers to impairment ratings that are based on the extent of functional loss, such as loss of motion of the wrist.

II. Limitations in the activities of daily living refers to limitations on the veteran’s ability to engage in the activities of daily living, such as bending, kneeling, or stooping, resulting from the impairment, and to participate in usual life activities, such as socializing and maintaining family relationships.

|

8 |

Figure 4-1 corresponds to Figure A2 in the Relationship Study. |

FIGURE 4-1 The consequences of an injury or disease.

IIIA. Work disability: loss of earning capacity refers to the presumed loss of earning capacity resulting from the impairment and limitations in the activities of daily living.

IIIB. Work disability: actual loss of earnings refers to the actual loss of earnings resulting from the impairment and limitations in the activities of daily living.

IV. Nonwork disability refers to limitations on the veteran’s ability to engage in usual life activities other than work. This includes ability to engage in activities of daily living, such as bending, kneeling, or stooping, resulting from the impairment, and to participate in usual life activities, such as reading, learning, socializing, engaging in recreation, and maintaining family relationships.

V. Loss of quality of life refers to the loss of physical, psychological, social, and economic well-being in one’s life.

The essential point of the distinction between the purposes of the disability benefits and the operational basis for the benefits is this: While the purpose of the workers’ compensation benefits and the current veterans disability compensation program is to compensate for work disability,

the operational basis for the benefits is almost invariably one of the other concepts shown in Figure 4-1, such as ratings based on an assessment of the extent of anatomical loss (IA) or functional loss (IB). In essence, the ratings of impairment are being used as predictors or proxies for the work disability that is assumed to follow from the impairments. Whatever the merits of the assumption, the use of proxies from the left side of Figure 4-1 as the operational basis for benefits that are provided for a purpose on the right side of the figure is ubiquitous in disability programs. Whether that assumption is warranted is one of the issues examined in Appendix C and in the balance of this chapter.

The Rating Schedule and Work Disability

One of the purposes of the veterans disability compensation program endorsed in Chapter 3 is to provide compensation for work disability resulting from service-connected injuries and diseases. For the Rating Schedule to support this purpose, several questions need to be resolved.

Question One: What Is the Measure of Work Disability That the Rating Schedule Is Supposed to Compensate?

The current Rating Schedule states that “the percentage ratings represent … the average impairment in earning capacity … in civil occupations.”9 This corresponds to the loss of earning capacity concept (IIIA) in Figure 4-1. However, there is no meaningful test of the accuracy of the current Rating Schedule if a comparison is made between (1) the ratings produced by application of the criteria for evaluating medical conditions contained in the Rating Schedule and (2) the average reduction in earning capacity because in practice they are the same thing. The meaningful test is whether the ratings produced by the Rating Schedule (which are the estimates of loss of earning capacity) correspond to the actual average loss of earnings among veterans with the same rating degree (IIIB) in Figure 4-1. This is the test that has been consistently used by researchers in the disability field, and corresponds to the test used in the Relationship Study for the workers’ compensation programs in Wisconsin and California and VA’s veterans disability compensation program.

The methodology used to calculate the actual loss of earnings resulting from a work-related or service-related injury or disease is explicated in the Relationship Study. A comparison is made between persons with disabilities

|

9 |

The full text of § 4.1 of the Code of Federal Regulations is provided in Section A.4.b of Appendix C. |

and persons without disabilities who have similar age, education, and other factors that affect earnings.

Question Two: How Should the Rating Schedule Be Evaluated?

The Rating Schedule should be evaluated by the ability of the ratings produced by the schedule to accurately predict the extent of actual losses of earnings for veterans with disabilities. The Relationship Study in Appendix C provides such evaluations for the Wisconsin and California workers’ compensation programs and for the veterans disability compensation program as of 1967. We are not suggesting that the results from these three programs should be used to evaluate the current Rating Schedule for the veterans program, in large part because we are aware that a study of the current schedule is being conducted by the Center for Naval Analysis. Rather, we are suggesting that the criteria that should be used to evaluate the accuracy of the current Rating Schedule for the veterans disability compensation program are the extent of horizontal and vertical equity in the relationship between the ratings and the actual loss of earnings for veterans with disabilities.

There is a long-standing tradition of the use of the equity criterion to evaluate programs for persons with disabilities. An example is the Report of the National Commission on State Workmen’s Compensation Laws (National Commission on State Workmen’s Compensation Laws, 1972), which defined equitable as

Delivering benefits and services fairly as judged by the program’s consistency in providing equal benefits or services to workers in identical circumstances and its rationality in providing benefits and services in proportion to the impairment or disability for those with different degrees of loss.

One variant of the equity test—intra-injury horizontal equity for ratings—requires that the actual wage losses for workers or veterans with the same disability ratings and the same type of injury should be the same or similar. In the case of the Rating Schedule, this test is whether all veterans with the same rating for a given condition have approximately the same earnings. For example, say veterans rated 70 percent for loss of a hand average 50 percent less earnings than veterans without service-connected conditions. One would not want to see a substantial number of veterans earning significantly less than the average. The evidence from the Wisconsin workers’ compensation program suggests this equity test is very difficult to satisfy (see Figure C-5 in Appendix C).

Another variant of the equity test—inter-injury horizontal equity for ratings—requires that the actual wage losses for workers with the same

disability ratings, but different types of injuries, should be the same or similar. Regarding the Rating Schedule, the test is whether veterans rated at the same degree for different conditions experience approximately the same loss of earning capacity. For example, are the average earnings of veterans rated 50 percent for depression and the average earnings of veterans rated 50 percent for a bad knee or loss of all fingers about the same? To put it another way, the Rating Schedule is not fulfilling the statutory intent if veterans at any given rating degree for impairments in one body system average substantially lower earnings than those with the same rating degree in another body system.

The evidence indicates that the Rating Schedule in use in 1967, as well as the two workers’ compensation programs, had serious deficiencies meeting this test. Each of the programs systematically treated some injuries or medical conditions differently than other injuries in terms of the extent of earnings losses associated with similar disability ratings (see Figures C-6, C-11 and C-12, and C-14 and C-15 in Appendix C for results from the Wisconsin workers’ compensation, California workers’ compensation, and VA disability compensation programs circa 1967, respectively).

A third variant of the equity test—vertical equity—requires that actual wage losses increase in proportion to increases in disability ratings. To meet this test, the Rating Schedule would consistently assign higher ratings to veterans with a given disabling condition who have lower average earnings. For example, veterans rated 30 percent for arteriosclerotic or coronary heart disease should earn less, on average, than those rated 10 percent, while those rated 60 percent should earn, on average, less than those rated 30 percent, and so on. At the aggregate level (the entire sample of workers or veterans), the evidence indicates that the Wisconsin rating system did an excellent job, the California rating system did a moderately good job, and the VA Rating Schedule in use in 1967 did a fairly poor job meeting the vertical equity criterion (see Figures C-4, C-13, and C-16 in Appendix C, respectively).

The answers to the first two questions in this section are the basis for our next recommendation.

Recommendation 4-2. VA should regularly conduct research on the ability of the Rating Schedule to predict actual loss in earnings. The accuracy of the Rating Schedule to predict such losses should be evaluated using the criteria of horizontal and vertical equity.

Question Three: What Factors Should Be Included in the Rating Schedule in Order to Improve the Accuracy of the Predictions of Actual Loss in Earnings?

The current Rating Schedule largely relies on assessments of medical impairment (concepts 1A and 1B in Figure 4-1) to determine the disability ratings. Would the inclusion of other permanent consequences of an injury or disease in the rating formula improve the accuracy of the predictions of actual loss of earnings?

One threshold issue is whether to base the disability ratings on direct measures of the actual loss of earnings for each veteran since that is the purpose of the benefits. There are two reasons why disability systems have generally avoided this approach. First, the earnings of a particular person are affected by a myriad of factors, and the workers’ compensation programs that have used the actual wage loss approach have generally abandoned it because it was found to be unworkable.10 Second, as discussed in Appendix C, the direct link between disability ratings (and the accompanying disability benefits) and the actual loss of earnings can create incentive problems for active participation in the labor force.11

The more relevant issue is whether the predictions of actual loss of earnings (IIIB in Figure 4-1) would be improved by adding more information about the veteran, such as age, education, or work experience, which typically are used to predict loss of earning capacity. However, the examination in Appendix C of the two workers’ compensation programs and VA’s disability compensation program as of 1967 provided some evidence that the accuracy of the predictions of actual wage loss was worse in terms of horizontal and vertical equity. We are not endorsing this finding as typical or necessary but rather as a warning that an attractive assumption—including data from more factors in the disability process is worthwhile—needs to be tested empirically, which leads to our next recommendation.

Recommendation 4-3. VA should conduct research to determine if inclusion of factors in addition to medical impairment, such as age, education, and work experience, improves the ability of the Rating Schedule to predict actual losses in earnings.

Question Four: How Can the Ability of the Rating Schedule to Predict Actual Losses of Earnings Be Improved?

The evidence from the research produced by Recommendations 4-2 and 4-3 can be used to improve the accuracy of the predictions of earnings losses made by the Rating Schedule. The study in Appendix C provides examples of how certain medical conditions may consistently have more (or less) earnings losses than predicted by the disability rating systems used in the workers’ compensation programs and VA’s disability compensation program as of 1967. A current study of the disability compensation program is likely to produce similar findings. Likewise, research can determine whether the inclusion of additional factors (such as measures of the limitations in activities of daily living) produces more accurate estimates of the actual losses of earnings.

These research results can be used in at least two ways to improve the accuracy of the Rating Schedule. First, the disability ratings assigned to a particular medical condition can be increased (or decreased) to incorporate the research results. Second, the value of the ratings in the Rating Schedule can be maintained, but a series of modifiers can be used to translate the “standard rating” from the Rating Schedule into an “adjusted rating” that will serve as the basis for calculating benefits. This second approach may be preferable because the expertise and knowledge needed by the people conducting the disability ratings will not have to be updated each time that research indicates changes are needed to improve the accuracy of the predictions of losses of earnings.

Recommendation 4-4. VA should regularly use the results from research on the ability of the Rating Schedule to predict actual losses in earnings to revise the rating system, either by changing the rating criteria in the Rating Schedule or by adjusting the amounts of compensation associated with each rating degree.