5

Idaho National Laboratory

The U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Office of Nuclear Energy (NE) is the lead program secretarial office (PSO) for the Idaho National Laboratory (INL), and as such, a significant part of DOE’s management responsibility and budget is devoted to INL. In FY 2006, for example, the Idaho Facilities Management budget of $99 million accounted for about 19 percent of the total NE budget. The PSO responsibility will continue to be a major one for NE, since to achieve the mission assigned to it by DOE, INL, as a large and aging facility, requires repair and maintenance as well as investment in new capabilities to support the NE program. INL and NE have developed the Ten-Year Site Plan (DOE, 2006a) to guide management of the site facilities to deal with these issues. This chapter presents the committee’s conclusions and recommendations regarding the site plan and NE’s management of this important asset. The chapter begins with a brief background on the INL and the site and a more detailed discussion of the issues facing the laboratory.

BACKGROUND

The Idaho site was established as a center of nuclear energy research in 1950, when the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, the predecessor of DOE, obtained land from the U.S. Navy to establish the National Reactor Testing Station. Later, lands were added for use in developing and testing nuclear reactors and related facilities. The site became the first location at which nuclear reactors were built to test the concept of nuclear power as a source of energy for peaceful commercial applications. In 1951, the INL achieved one of the most significant scientific accomplishments of the century—the first use of nuclear fission to produce a usable quantity of electricity at the Experimental Breeder No. 1 (EBR-1). The EBR-1 is now a registered national historical landmark open to the public. In its 57-year history, scientists and engineers at the site designed, constructed, and operated 52 nuclear reactors.

During the 1970s, the site began a succession of changes in mission and program. In 1974 its name changed from the National Reactor Testing Station to the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory (INEL) to reflect its broadened mission into areas like biotechnology, energy and materials research, and conservation and renewable energy. The site name changed again in the spring of 1997 to the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory (INEEL), reflecting a major refocusing of the laboratory’s work over the long term to engineering applications and environmental solutions for the United States. Thereafter, the site experienced declining support, and much of the activity was directed toward decontamination and disposal of its aging facilities. In July 2002, however, sponsorship of the site was formally transferred to DOE’s Office of Nuclear Energy, Science and Technology, which became today’s NE. The move to NE supports the nation’s expanding nuclear energy initiatives, placing INL at the center of work to develop advanced Generation IV nuclear energy systems; nuclear energy/hydrogen coproduction technology; advanced nuclear energy fuel cycle technologies; and solutions to the Department of Homeland Security’s need for a secure national infrastructure. Finally, on February 1, 2005, the site became INL. This change reflects a move back to the laboratory’s historic roots in nuclear energy and national security. The vision for INL is to transform its assets and capabilities to become the world’s preeminent laboratory for nuclear energy research, development, and demonstration (RD&D) within 10 years.

INL is operated by the Battelle Energy Alliance, LLC (BEA), which consists of Battelle; BWX Technologies, Inc.; Washington Group International; the Electric Power Research Institute; and an alliance of university collaborators, led by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

FACILITY ISSUES AT INL

The INL site presents two challenges in the management of its physical facilities: (1) new or rejuvenated facilities are required to support the new mission and vision for the labora-

tory and (2) NE/INL is the landlord for a large, multitenant site in deteriorating condition. Each of these challenges is described briefly below.

Building Scientific and Engineering Capability

INL’s Strategic Plan (DOE, 2006b, p. 3) states its assigned mission as “ensur[ing] the nation’s energy security with safe, competitive, and sustainable energy systems and unique homeland security capabilities.” The laboratory’s vision is that, “within ten years, INL will be the preeminent national and international nuclear energy center with synergistic, world-class, multi-program capabilities and partnerships.” To achieve its ambitious goals, INL must attract and retain world-class scientists and engineers in a multiplicity of engineering and scientific disciplines. INL must have a budget to acquire and maintain state-of-the-art facilities and equipment that will be used by researchers of the highest technical competence to lead the development of and sustain nuclear power as a valued energy option nationally and internationally.1

To specify the facilities and other capabilities required to realize its vision, INL has prepared three plans, all of which the committee has carefully studied and discussed with NE and INL management.

-

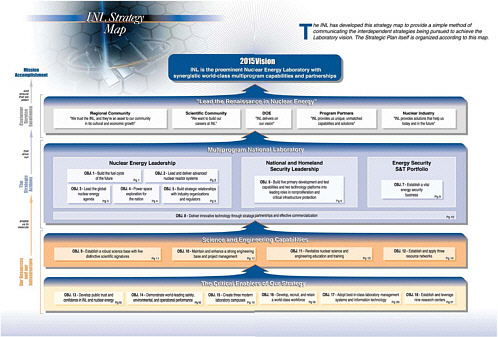

The INL Strategic Plan sets out 18 specific objectives that support the vision. Figure 5-1 reproduces the strategy map from the plan that specifies these objectives and the relationship among them. The Strategic Plan has been approved by NE and, according to the Idaho Operations Office (ID), is entirely consistent with the statement of work contained in the operating contract with BEA.

-

The Ten-Year Site Plan presents the building-by-building, year-by-year actions recommended to acquire the facilities that INL requires for its mission. Appendix B of the plan lists all of the facilities the laboratory believes it needs for its mission and programs. The Ten-Year Site Plan available to the committee was prepared in June 2006 and is currently being updated to ensure consistency with the INL Business Plan. As a result, the documented track from strategy to business plan to detailed facilities plan is not as tight as it might be. Based on its site visit and discussions with laboratory and ID management, however, the committee concludes that there are no major inconsistencies. Indeed, as a matter of process, the logical progression of plans that INL has developed and is developing present a clear picture of what laboratory management believes is necessary to become “the preeminent, internationally recognized nuclear energy research, development, and demonstration laboratory.”

-

The INL Business Plan disaggregates the broad objectives into business lines and the laboratory capabilities that distinguish it. While the Business Plan has not yet been made public, the committee discussed it extensively with INL and DOE staff and found it to be consistent with the Ten-Year Site Plan and the Strategic Plan.

It is important to note that the formal INL plan documents were all prepared by INL staff. The committee recognizes and emphasizes the need for NE and ID to fully participate in the planning activity and to eventually agree on what activities are to be carried out and the schedule.

To summarize this sequence of plans, it is useful to distinguish between facilities needed to support the capabilities envisioned for the laboratory and those that would be constructed by programs that might locate at the site, in part because of those capabilities. The latter, for example, might be the reactor or reprocessing demonstration facilities for the Global Nuclear Energy Partnership (GNEP) or the prototype of a Generation IV reactor for process heat applications. Site tenants other than NE might also build facilities there–for example, the Department of Homeland Security or the U.S. Navy. INL will compete with other laboratories for these program facilities.

Given the relatively large fraction of a PSO’s budget that must be devoted to landlord-related activities at a site,2 it is most important to closely couple the project-related facilities and those needed to achieve world-class status for the laboratory and attract capable personnel. Advanced computing capabilities, or highly technical facilities such as test reactors or postirradiation examination laboratories and hot shops are examples. These facilities are very expensive to obtain and keep operational and up to date, so there is a continuing burden on the PSO—first, for a large initial investment and then for the expense of long-term support. Thus the PSO needs to utilize a strategy of making sure facilities to establish world-class capabilities closely overlap with those needed for specific projects. This suggests that investments in those types of capabilities and facilities need to be paced and scheduled so they match project needs, and the capabilities provided should be developed based on specifications that satisfy specific project needs.

As an example, NE has indicated a potential need for major computation and simulation capabilities. This is analogous to the need for similar capability in DOE’s National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) Weapons Stockpile Stewardship Program. The needs of the specific weapons simulation and modeling projects were first established to define the minimum capability needed for those projects.

This then became the target for the computing facilities and capability to be provided, and funding was sought on this basis. In addition, as the technical programs were further developed and refined, the additional computational capability was defined and used to create a funding profile over several years. This approach provides a credible metric for infrastructure investments, for projecting future needs, and for replanning or adjustments as time passes and actual budgets and technology needs change (DOE, 2007a).

Whether or not the site becomes home to any of these program facilities, however, the INL facilities should be configured to efficiently support the laboratory’s ongoing mission. The laboratory plan would group these facilities into three campuses:

-

The Science and Technology Campus would consolidate a wide variety of scientists and research facilities into a single area in Idaho Falls. Presently, much of the INL scientific and engineering staff is scattered among 36 buildings in Idaho Falls or work at the site itself. Most of INL’s scientific and engineering staff would be located at the new campus, and their research would cover all of INL’s lines of business. The new campus would house administrative offices as well as research laboratories.

-

The Reactor Technology Complex would focus on testing of advanced and proliferation-resistant fuels for NE, the U.S. Navy, and other users. Nearly half of the buildings at this site were built before 1967. The new Reactor Technology Complex would be built around the existing Advanced Test Reactor (ATR), which would have an upgraded mission capability to support an extended life.

-

The Material and Fuels Complex would be the center of research on new reactor fuels, the nuclear fuel cycle, and related materials. It would incorporate and modernize a number of existing facilities for this purpose. Over half of the existing buildings at this site are more than 30 years old.

BEA, the operating contractor, expects to build or upgrade 400,000 ft2 of space in implementing these plans over the next 10 years.

Managing Site Infrastructure

BEA is also responsible for management of the overall site and its infrastructure. As noted earlier, the site infrastructure is old and deteriorating. About 45 percent of it is under the jurisdiction of DOE’s Office of Environmental Management, which is responsible for decontamination, decommissioning, and disposal of assets no longer required for INL’s present mission. NE is responsible for maintaining or closing the balance. As a first goal, INL/BEA is committed to eliminating 1.1 million ft2 of existing space during the 10-year horizon of the site plan. The result would be to reduce the space under NE active stewardship at the site by about one-third from the present 3.2 million ft2.

A second goal is to maintain the remaining infrastructure in good condition. DOE employs several metrics to assess the condition of infrastructure. At INL, these metrics rank the overall condition of the facilities as adequate and the overall utilization as good. However, the deferred maintenance backlog is high in relation to the value of the assets involved. In FY 2004 the ratio stood at 11.8 percent for INL’s nonprogrammatic assets; the DOE target for this ratio is 2 to 4 percent (see Table 5-1). NNSA also maintains a target ratio of roughly 2 to 4 percent for its laboratories but has struggled to achieve this.

ASSESSMENT OF THE TEN-YEAR PLAN

The Ten-Year Site Plan recommends a series of investments to bring the site into compliance with the INL vision and DOE’s goals for infrastructure management. While the committee has not attempted to analyze the Ten-Year Plan in detail, it has been able to test it for reasonableness in reaching both objectives.

Building Scientific and Engineering Capability

INL’s plans for building the scientific and engineering capability needed to realize its vision are logically constructed and link broad visions with clear and consistent objectives. The Business Plan and the Ten-Year Site Plan, while still in flux, appear systematically to translate the strategy into specific capabilities and facilities plans. The committee has also

TABLE 5-1 Comparison of Multipurpose Laboratory Infrastructure Conditions and Uses

|

Laboratory |

Asset Utilization Index |

Asset Condition Index |

Deferred Maintenance Ratio (%) |

|

Idaho National Laboratory |

0.95 |

0.92 |

11.8 |

|

Argonne National Laboratory |

0.96 |

0.96 |

2.0 |

|

Brookhaven National Laboratory |

0.97 |

0.83 |

1.9 |

|

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory |

0.97 |

0.92 |

2.0 |

|

Oak Ridge National Laboratory |

0.98 |

0.92 |

2.0 |

|

SOURCE: DOE (2006c). |

|||

reviewed the work statement for the operating contractor, BEA, and finds that the planning is consistent with the work statement. Its interviews with laboratory personnel, ID, and NE have not revealed any disagreement with this hierarchy of plans, at least conceptually.

The committee has also examined these plans for consistency with the research program the committee recommends elsewhere in this report. The Business Plan lists “distinguishing capabilities” and “distinguishing performance” for INL. The committee reviewed these capabilities and performances for consistency with the specific programmatic plans. Overall, it concludes that the high-level objectives stated in the Ten-Year Site Plan are generally consistent with the program objectives. However, the committee emphasizes the importance of directly attaching facilities’ capabilities to specific programs. Tighter coupling is needed for two reasons. First, particularly in view of tight budgets for the foreseeable future, NE needs to ensure facilities at INL do not duplicate those at other laboratories. Second, close attention is needed to ensure facility dollars at INL are closely coupled to specific programs and projects and the requirements are derived from the needs of the program/project, in terms of both capability and timing.

Managing the Infrastructure

As noted above, DOE measures several aspects of infrastructure condition and use. The committee has compared the metrics for INL with those of other multipurpose laboratories, as shown in Table 5-1.

It appears from these data that the metrics for the utilization and condition of INL’s assets are within a range comparable to that of other national laboratories. However, deferred maintenance is clearly out of line. The Ten-Year Site Plan estimates that an investment in maintenance of $150 million to $175 million per year would bring deferred maintenance within the high end of the target range by 2014. While the committee has not made an independent estimate, the high level of deferred maintenance at INL would seem to require significant investments to achieve parity with other DOE assets.

It appears the ratio is high at INL because the facility tends to be underfunded: There are many projects seeking funding, and maintenance work has been deferred to support more pressing issues. Other PSOs—for example, NNSA—have had similar difficulties and have evolved approaches to reduce the balance, including limited periods of specific investment in facilities to obtain or reestablish needed levels of performance. In addition, activities at other national laboratories have been graded so that maintenance in direct support of facilities critical to particular programs is ensured; maintenance of needed, but not program-critical, facilities is funded next (an example is fire protection), and other facilities receive the lowest priority.

Resources Available to Implement the Plan

The Idaho Facilities Management Account requested $95.3 million in FY 2007 for support of the INL site (DOE, 2007b). The FY 2008 request is $104.7 million. This account appears to be the chief source of funding for infrastructure support, although another $129 million is requested in FY 2008 for safety, security, and the management of radiological facilities. The FY 2007 request is shown in Table 5-2.

This account contains funds for building capacity and for infrastructure management. In FY 2007, it contains no new capital expenditures or general plant projects funding.

Other funds come through the indirect charge INL makes on program funding. The FY 2007 budget for INL is shown in Table 5-3.

Of these, only the space cost looks much like a facility charge. INL’s laboratory-directed research and development (LDRD) is in the mid-range of the national labs, with the NNSA labs leading the pack (see Table 5-4). However, the committee considers that INL is a lead technology laboratory, more like the NNSA lead technology laboratories (Los Alamos National Laboratory, Sandia National Laboratories, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory) than the more general-purpose DOE laboratories such as Oak Ridge National Laboratory or Argonne National Laboratory. The percentage of total funding spent on LDRD at the NNSA laboratories is about twice that at INL, and the total funding allocated to LDRD at these laboratories is 4.5 to 6 times more. The committee also notes that INL is just starting a steep climb to establish its prominence and capability as the

TABLE 5-2 FY 2007 Request for the Idaho Facilities Management Account (millions of dollars)

|

Account |

MFC |

RTC |

Sitewide |

ATR Life Extension |

|

Infrastructure |

29.7 |

11.6 |

15.9 |

18.5 |

|

Capital projects |

0.6 |

5.0 |

2.3 |

|

|

Operating projects |

0.2 |

0 |

0.4 |

0 |

|

Capital equipmenta |

0.3 |

0.2 |

2.4 |

1.4 |

|

NOTE: ATR, Advanced Test Reactor; MFC, Material Fuels Complex; RTC, Reactor Technology Center. aExcept for the ATR life extension, all capital equipment funding in FY 2007 is carryover from FY 2006. SOURCE: Materials supplied to the committee by DOE on November 28, 2006. |

||||

TABLE 5-3 FY 2007 Budget for the Idaho National Laboratory (millions of dollars)

|

Account |

Funding |

Description |

|

General and administrative |

131.9 |

Primarily management systems costs and fixed costs like fees, taxes, and insurance |

|

Laboratory-directed research and development |

21.1 |

Long-term research initiatives |

|

Program development |

9.2 |

Business line development |

|

Organization management |

49.7 |

Management overhead |

|

Space |

44.5 |

Common use facilities and space management |

|

Common support |

23.8 |

Infrastructure services line buses, cafeteria, fire, and landfill |

|

SOURCE: Materials supplied to the committee by DOE on November 28, 2006 |

||

TABLE 5-4 Reported FY 2006 Overall Laboratory Costs and LDRD Costs at Participating DOE Laboratories (millions of dollars)

lead laboratory for nuclear technology in the DOE complex, while the NNSA laboratories are already established. Since LDRD funds are so important for attracting and motivating the kind of people needed to achieve a strong capability, NE should consider expanding the availability of LDRD funds at INL.

INL is attempting to set up ATR as a user facility. This would produce some revenue, but only at an incremental cost level.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The committee finds as follows:

Finding 5-1. Overall the committee considers that INL is an important facility and provides important capabilities to support NE’s mission, which is to use nuclear technology to provide the United States with safe, secure, environmentally responsible, and affordable energy. INL has developed a strategic vision and a long-term (10 years) plan for this purpose.

Finding 5-2. The funding being provided to INL by NE is substantially less than what is needed to be consistent with INL’s current vision. INL has been further short-changed in that it has not received sufficient funding to stay even with the other national laboratories in terms of maintenance and funding of known efforts, which include commitments to the state of Idaho for the cleanup of certain state facilities. NE should consider expanding the availability of LDRD funding at INL; the target range should be competitive with or greater than that of the NNSA lead technology laboratories, 6-8 percent.

Finding 5-3. The NE/INL budgeting system and the budget documents themselves are opaque and hard to understand. It is difficult to trace budget amounts to particular projects and programs and to specific activities within the INL subbudget. The committee observes that the de facto budget process seems to be that INL and the direct overseers at ID and NE come up with a list of tasks they consider to be desirable or needed in a given year, and then NE senior management allocates some fraction of the overall NE budget that remains after allocations are made to other high-priority programs. The sum assigned to the INL facilities budget is then distributed over the original task list so that the highest priority tasks are funded and the others are postponed.

Finding 5-4. A much more transparent, structured, and jointly supported (by NE, ID, and INL-BEA) planning and budgeting process is needed. This will ensure that all parties are in full agreement about the long-term plan and that budget decisions are made more carefully and on a more balanced basis. It will also enhance the credibility of the budget and its bases to reviewers in Congress and the Office of Management and Budget and will, in the long term, provide more stable and effective funding for the agreed-on plan.

Finding 5-5. NE has limited experience of being the PSO for a national laboratory. As such, its procedures for this responsibility are not yet well defined. NE could benefit from discussions with other organizations at DOE (e.g., the Office of Science and NNSA) with longer-standing, more mature PSO efforts.

The committee’s recommendations fall into three broad categories: improve the NE organization to better discharge its responsibility as the lead PSO for INL; establish a joint baseline vision and plan for INL; and modify the form of the INL facilities budget documentation to improve credibility and usefulness.

NE as the Lead Program Secretarial Office for INL

Recommendation 5-1. NE should set up and document a process for evaluating alternative approaches for accomplishing NE-sponsored activities, assigning the tasks appropriately, and avoiding duplication. For example, although INL is identified as the lead laboratory for nuclear-energy-related tasks, this does not mean that all such work is to be assigned to INL. Rather, NE should take into account the existing skills and facilities and make best use of available and new resources. The basis for the decision should be clear to INL and the other laboratories and facilities.

Recommendation 5-2. NE should set up a formal, high-level working group jointly with ID and INL (BEA). Consideration should be given to also having one or more knowledgeable outsiders participate on an ongoing basis to provide a wider perspective. This joint group would review the long-term project plan recommended below and serve as a forum for discussion and resolution of issues, such as changes to the plan and the best way to make the inevitable adjustments that will be needed. It will also be a ready source of informal, expert advice to NE senior management on INL facilities management.

Recommendation 5-3. NE should meet with DOE and NNSA organizations that are PSOs for other laboratories to review and discuss their practices and processes. Based on the lessons they learned, it should develop and document its own internal processes and procedures for discharging its responsibilities as the PSO for INL.

INL Facilities Baseline, Vision and Plan

Recommendation 5-4. NE, ID, and INL (BEA) should establish an agreed-on multiyear, resource-loaded, high-level schedule and plan for the INL facilities, such as the Primavera Project Planner (P3). This plan should establish the level of funding needed from NE, recognizing the contributions expected from other agencies that use the site and funding from projects located at INL. It should be based on funding levels that are practical for the foreseeable future, not a wish list. It should be used for developing an annual budget for the INL facilities and should be updated annually as part of the budget cycle. This will support directly assessing the effect of annual budget changes and answering questions on the impact of additional money or the effect of shortfalls.

Recommendation 5-5. The initial version of this plan should be based on the current BEA baseline assessment, vision, and supporting Ten-Year Site Plan. This does not mean that the committee gives the BEA plan and documents across-the-board endorsement. Rather, these documents appear to contain the most complete and up-to-date information available, and their structure is such that there is reasonably good traceability from objective to needed funding. They should pay attention to the connections between major programs and facilities. In particular, the capability and timing of facilities should be tightly tied to the program needs.

Recommendation 5-6. For INL to accomplish its expected mission, a number of large, sophisticated, and unique facilities will be needed. These could include large hot cells and associated laboratories for postirradiation examination of materials and test reactors such as the ATR. The intent is for INL to have magnet facilities attracting researchers and industrial users. For these facilities to attract users, the full costs cannot be charged, and the user would pay only the justified incremental costs associated with use. This arrangement is typical of user facilities in the Office of Science laboratories. The result is that the user facilities must also receive dedicated funding from the PSO. NE and INL have begun work to make the ATR at INL into such a user facility. The committee endorses this approach for ATR and recommends as follows:

-

NE should promptly address the inclusion of needed funding to support the base costs of the ATR in the INL facilities funding and develop an equitable basis for allocating justified user costs over the longer term.

-

As they develop a long-term plan for INL facilities, NE and INL should consider hosting other key capabilities—say, hot cells—as user facilities. Any such user facilities should be separately identified.

-

NE and INL should include LRDR tasks associated with establishing and strengthening INL personnel capability in the INL baseline, vision and plan.

Form and Content of the INL Facilities Budget Documentation

Recommendation 5-7. NE, ID, and INL (BEA) should improve the form and content of the INL facilities budget documentation. Currently, a wide variety of documents need to be reviewed to understand the budget and its basis, and even then discussions with the main participants are necessary. NE, ID, and INL (BEA) need to decide on the final form for the budget documentation, and both the Office of Science and NNSA documentation would be worthy of emulation. The improved budget documentation should have the following attributes:

-

Budget items should be readily traceable to specific items in the overall plan and schedule.

-

Big-ticket items that affect the budgets—for example, the resolution of cleanup commitments with fixed future end dates—should be explicitly identified and accounted for in funding plans.

-

The impact of budget amounts on maintenance items should be documented. For example, it appears maintenance is chronically underfunded, the maintenance backlog is rising, and the backlog appears to be out of line with that of other comparable national laboratories. Data that allow discerning trends and drawing comparisons need to be provided or clearly referenced in the budget. Traceability to a living, readily updated overall plan and schedule will also help in this regard.

-

The amount and sources of indirect funding at INL used to support facilities-related expenditures should be clarified.

-

Work funded by government agencies other than NE should be explicitly accounted for, along with the attendant impacts on resources needed to maintain and enhance INL facilities. The costs of managing for multiple users should also be shown.

REFERENCES

Department of Energy (DOE). 2006a. Idaho National Laboratory Ten-Year Site Plan. August.

DOE. 2006b. INL Strategic Plan: Leading the Renaissance in Nuclear Energy. Summer.

DOE. 2006c. Laboratory Plan FY2007-2011.

DOE. 2006d. FY 2006 Report to Congress, Laboratory Directed Research and Development at the DOE National Laboratories.

DOE, National Nuclear Security Administration. 2007a. NNSA Stockpile Stewardship Plan, (Unclassified) Final Coordination Draft–Working papers (April 2).

DOE. 2007b. Department of Energy FY 2007 Congressional Budget Request.