10

Multisector and Interagency Collaboration

Previous chapters have demonstrated that commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors are intrinsically multifaceted such that they cannot be understood or addressed effectively through any one sector or discipline alone. Rather, an adequate response requires participation from numerous actors, including victim and support service providers, health and mental health care providers, legislators, law enforcement personnel, prosecutors, public defenders, educators, and the commercial sector. These actors work within different sectors, such as the nonprofit, health care, legal, and commercial sectors, and at different levels of government, including local, state, and federal. Individuals, groups, and organizations working within these systems can become “siloed,” gaining expertise by working primarily within their individual domains or specific areas of expertise, and can have differing goals, missions, and perspectives on how commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors should be handled. This can create barriers to collaborating effectively to address these problems.

In the health context, multisector and interagency collaboration refers to various governmental, nongovernmental, social, and public organizations, groups, and individuals coalescing around a shared common focus with the potential to affect current and future health (Armstrong et al., 2006; Nowell and Froster-Fishman, 2011). (Note that while the committee uses the terms “multisector” and “interagency,” the literature and various fields of practice use the term “multidisciplinary” synonymously.) In a report on the future of public health in the 21st century (IOM, 2002), the Institute of Medicine cites the need for planned interaction among all

relevant community-related organizations (government, nongovernmental organizations [NGOs], businesses, schools, media, and health care delivery systems). Multisector and interagency collaborative approaches can become catalysts for the design and implementation of strategies and policies with a good chance of being timely, effective, relative, and sustainable (Buffardi et al., 2012).

This chapter focuses on the growing emphasis on multisector and interagency collaborative approaches to addressing the systemic issues of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. These approaches range from formal relationships based on memoranda of understanding (MOUs) to ad hoc and case-by-case arrangements drawing on networks of informal personal contacts. The chapter begins with an explanation of the value of such approaches. Next, because multisector and interagency work on commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States has been underexamined, the chapter presents lessons from related fields of practice and areas of research, including child maltreatment, domestic violence, and sexual assault. The chapter then describes a number of noteworthy multisector and interagency efforts in the area of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors, including task force models and other state- and county-based collaborations. The committee used agency and organization reports, its public workshops, and its site visits to learn about these efforts; the descriptions of these efforts are meant to complement and supplement the limited published research. It should be noted that these models and activities have not been empirically evaluated. Thus, while the committee does not intend to imply that it is endorsing these approaches, it does endorse additional examination of their effectiveness. After reviewing these efforts, the chapter describes continuing challenges to multisector and interagency collaboration and identifies opportunities for additional collaboration. The final section presents findings and conclusions.

VALUE OF MULTISECTOR AND INTERAGENCY

RESPONSES AND COLLABORATION

Collaboration among multiple sectors, agencies, and organizations has the potential to help diverse entities gain a mutual understanding of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors, which may enable them to address the crimes themselves, as well as the needs of victims/survivors, more effectively (Clawson et al., 2006; Piening and Cross, 2012). Through regular meetings and other information-sharing mechanisms, agencies and organizations from different sectors can formalize networks and forge institutionalized relationships among actors and across siloes. Collaboration can engender intervention at various levels,

such as awareness raising, information sharing, resource sharing, and coordinated response to real-time situations. According to the Department of Justice’s Office for Victims of Crime:

The advantage of multidisciplinary anti-trafficking Task Forces is in the maintenance of a strategic, well-planned, and continuously fostered collaborative relationship among law enforcement, victim service providers, and other key stakeholders. A multidisciplinary response to human trafficking raises the likelihood of the crime being discovered, provides comprehensive protection of the victim, and increases coordinated investigative and prosecutorial efforts against the perpetrator. (OVC and BJA, 2011, Sec. 3.2)

Noting the promise of multisector and interagency collaboration, the Department of Justice has provided funding for communities to establish anti-human trafficking task forces, which include “state and local law enforcement, investigators, victim service providers, and other key stakeholders” (Office of Justice Programs, 2013, p. 1). Other multisector and interagency efforts to address commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors have been established without direct federal funding. As a result of the influence and goals of different funding sources, as well as the needs and strengths of communities, different sectors take lead roles in organizing and catalyzing action in collaborative networks. Thus, one task force might be led by law enforcement, while another might be more NGO driven. Also variable is the extent to which a particular task force includes representatives from multiple sectors. And in addition to multisector collaborations, intrasector and specific cross-sector collaborations are possible.

In some cases, information and communication technologies facilitate connectedness and information sharing among collaborators (Stoll et al., 2012), although sharing of information is complicated by trust, privacy, legal, and data security concerns. In other cases, a formal MOU is helpful to designate the roles and parameters for collaboration and partnership (Piening and Cross, 2012). While this chapter focuses on a few models of multisector and interagency collaboration, the committee does not advocate a one-size-fits-all approach to collaboration and acknowledges a variety of formulations, strategies, and mechanisms that support collaboration. As noted, few of these approaches have been evaluated, so the committee does not intend to endorse or promote any particular model of practice. It merely notes that communities that have established channels for collaboration among people who work in diverse sectors appear to have had some success in addressing commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors.

Ideally, multisector and interagency approaches to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States would include all groups necessary to adequately address the needs of victims and the prosecution of exploiters, traffickers, and purchasers. A robust litera-

ture evaluating the components of a multisector response to human trafficking or what individuals, organizations, and systems should be included does not exist. Nevertheless, the committee views the individuals, organizations, and systems listed in Box 10-1 as important components of a multisector response to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors (Clawson et al., 2006; Gonzales et al., 2011; Nair, 2011; OVC and BJA, 2011; Piening and Cross, 2012; Polaris Project, 2012).

Perhaps as important as involving the relevant individuals, organizations, and systems is the process for collaborating. The committee learned from site visit participants, workshop presenters, and published reports that multisector and interagency collaboration benefits from having a co-

BOX 10-1

Components of a Multisector Response to Commercial Sexual

Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States

• Local law enforcement

• State law enforcement

• Federal law enforcement

• State social service agencies

• Nongovernmental social service agencies

• Nongovernmental advocacy organizations

• Local prosecutors

• State and county prosecutors

• Federal prosecutors

• Defense attorneys

• Judges

• Victims/survivors

• Media

• Private sector

• Researchers and academics

• Child welfare

• Juvenile justice

• Health care providers, including mental health care providers

• Faith-based groups

• Public officials

• Social activists

• Homeless advocates

• Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) advocates

• Educators

SOURCES: Clawson et al., 2006; Gonzales et al., 2011; Nair, 2011; OVC and BJA, 2011; Piening and Cross, 2012; Polaris Project, 2012.

ordinator or coordinating agency, frequent formal and/or informal communication, personal commitment from individuals, consensual (rather than top-down) decision making, and organizational support (Nicholson et al., 2000).

LESONS LEARNED FROM MULTISECTOR AND

INTERAGENCY APPROACHES TO CHILD MALTREATMENT,

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE, AND SEXUAL ASSAULT

While little published research exists on multisector and interagency responses to the commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors, the literature indicates that coordinated multidisciplinary approaches have long been endorsed as an effective way to respond to the related and overlapping areas of child abuse and neglect (Alexander, 1993; Hochstadt and Harwicke, 1985; OJJDP, 1998). Key features of successful child maltreatment multidisciplinary teams noted in the literature include

• commitment from the ground up, as well as from leaders (mandating adoption of the multidisciplinary team approach will not succeed unless those responsible for its implementation are committed to its success and believe it is worthwhile);

• clear definitions of (and mutual respect for) the roles of each of the involved agencies and professionals;

• creation and adoption of a clear mission statement (representing shared values and commitment);

• development of written agreements (MOUs and/or joint protocols for child abuse investigation and intervention) specifying the ways in which team members will communicate and coordinate regarding cases and victims;

• a regular process for honest review and discussion of cases and issues (for example, regular case reviews) and a culture that allows for respectful disagreement and questioning of one another;

• open and respectful communication and ongoing relationships; and

• joint training and team social activities.

Examples of multidisciplinary teams and interagency approaches created to address child maltreatment and domestic violence include children’s advocacy centers (CACs) and family justice centers (FJCs). Examples of multidisciplinary teams and interagency approaches that have been used to address sexual assault include sexual assault response teams (SARTs). Each of these models is described in the sections that follow.

Children’s Advocacy Centers

A range of multidisciplinary team models have been used to respond to child maltreatment cases. Facility-based CACs are one such model. The purpose of a CAC is to provide a child-friendly environment and to centralize and coordinate the investigation of child abuse cases and related social, physical, and mental health care, as well as advocacy services (Cross et al., 2008). CACs require the use of multidisciplinary teams (which include law enforcement investigators, child protection workers, prosecutors, and mental health and other health care professionals, among others) to coordinate forensic interviews, medical evaluations, therapeutic interventions, and victim advocacy in connection with case review and case tracking. First developed in 1985, CACs now number more than 900 nationwide; 750 of these centers meet national accreditation standards set and administered by the National Children’s Alliance (2013). Despite the existence of these standards, individual CACs vary greatly in how they were created, how they are organized, and how services are administered. Leadership within CACs comes from a variety of distinct traditions and perspectives, including prosecution, law enforcement, and physical and mental health. Collocation of various professionals and victim services is a feature of most CACs, although the specific agencies and services at a CAC facility vary significantly from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

Studies comparing the efficacy of CACs with that of other approaches to multidisciplinary and interagency coordination have yielded mixed results, underscoring the complexity and difficulty of evaluating such efforts (Cross et al., 2008; Faller and Palusci, 2007). For example, Cross and colleagues (2008) conducted a multisite evaluation of CACs, collecting data between 2001 and 2004 on more than 1,000 cases of sexual abuse. Outcome data from four CACs were compared with outcome data from communities without CACs. The authors found that

• there was significantly more evidence of coordinated investigations for the CACs;

• more children involved with a CAC received a forensic medical examination;

• a referral for mental health services was made in 72 percent of CAC cases, versus only 31 percent of comparison community cases;

• parents and caregivers in the CAC sample were more satisfied with the investigation than those in the comparison sample (although the only difference found for children was that they were less frightened if they were interviewed at a CAC than at a non-CAC site);

• all of the CACs in the study were regarded as community leaders and experts in the area of child abuse; and

• only CACs with strong involvement from law enforcement and district attorneys’ offices showed an impact on criminal justice outcomes.

Cross and colleagues (2008) note several limitations of their research, including the small sample size and the absence in the sample of specific types of CACs (e.g., smaller CACs in suburban or rural locations and CACs based in prosecutors’ offices), making it difficult to generalize their findings to all CACs.

Other studies have demonstrated more clearly the value and effectiveness of multidisciplinary teams and CACs. In 2006, for example, Shadoin and colleagues conducted cost-benefit and cost-effective analyses of programs and services for child maltreatment. The researchers used contingent valuation methodology to study and elicit individuals’ willingness to pay for the services provided by a local CAC and concluded that the CAC program generated important net benefits that were valued by individual members of the community (Shadoin et al., 2006). In another example, a study in Florida found that benefits of multidisciplinary teams included increased substantiation of cases and a shorter investigative period, regardless of whether a CAC model or a Florida child protection team model (a local variation on the multidisciplinary team approach) was used, suggesting that interagency coordination was the key factor responsible for improvements over traditional child protective services interventions (Wolfteich and Loggins, 2007). Finally, another study found that the use of CACs to respond to child maltreatment increased felony prosecutions of child sexual abuse cases (Miller and Rubin, 2009).

As discussed in earlier chapters of this report, child maltreatment cases bear strong similarities to cases involving commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. Indeed, in most communities, many of the same professionals are responsible for some aspect of the response to both child abuse and commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors, especially when the latter are recognized and treated as a subset of the former (as this report argues they should be). It therefore follows that building upon and using existing CACs, multidisciplinary teams, and MOUs (or other protocols outlining agreements regarding collaboration and coordination of efforts) focused on child maltreatment may be one sensible starting point for undertaking collaboration to assist victims and survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors and to investigate and prosecute cases. Potential advantages to using existing CACs to organize improved responses to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors include

• an established, extensive network (more than 900 in the United States) and support that exist for CACs throughout the United States;

• the availability at CACs of trained child forensic interviewers, medical evaluation and services, and victim advocacy and mental health services; and

• the ability of CACs to innovate and develop services responsive to local needs.1

Kristi House, a children’s advocacy center in Miami, is an example of how the structure and resources of an established CAC can be leveraged to provide services to victims and survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. In 2007, Kristi House created Project GOLD (Girls Owning their Lives and Dreams) to provide links to health services, case management, and therapy services specifically for victims of these crimes. In addition, Kristi House has plans to open an emergency drop-in shelter for victims of these crimes in early 2013 (Kristi House, 2012).

While CACs are one well-established model of care, it is important to recognize the ways in which victims and cases of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors differ from victims and cases of child maltreatment traditionally dealt with by CACs and other multidisciplinary teams. As noted in Chapters 6 and 7, additional professionals, agencies, and services may be required to ensure an appropriate response to victims of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. Some of the differences noted in earlier chapters include the need for enhanced security procedures because of the possibility of exploiter/trafficker retaliation; the need for advanced training in forensic interviewing so interviewers understand how best to talk to victims of these crimes; and the need for enhanced and expanded victim and support services, such as stronger case management and specialized mental health care. In addition, many CACs may be focused on younger victims (e.g., ages 6-12) and consequently may not be as welcoming for adolescent victims and survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking.2 Box 10-2 describes an example of how the CAC model has been adapted to address the unique needs of those at risk for and victims and survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors.

__________________________

1E-mail communication received by T. Huizar, Executive Director, National Children’s Alliance, November 19, 2012.

2E-mail communication received by T. Huizar, Executive Director, National Children’s Alliance, November 19, 2012.

BOX 10-2

High-Risk Victims Model: Adaptation of the Children’s

Advocacy Center Model to Meet the Needs of Those

at Risk for and Victims and Survivors of Commercial

Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors

Recognizing the need to prevent and address the commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in their community, a variety of agencies in Dallas, Texas (including the Dallas Police Department, victim and support service agencies, and nonprofit organizations) came together to form a High-Risk Victims Working Group. This group meets at least once a month and focuses specifically on chronic runaways—a population that the Dallas Police Department identified as being at high risk for commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking. The group determined that the children’s advocacy center (CAC) approach would need to be modified or expanded to meet the distinct needs of minors who are at risk for or are victims and survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking. As a result of the group’s collaboration and reconceptualization, high-risk individuals and victims/survivors are referred to and served by the Letot Center, a runaway shelter, rather than the existing CAC model. The Letot Center has developed and delivers tailored programs and services for these youth. The Dallas Police Department considers this model to be an “adolescent advocacy center” and more appropriate than the CAC model for servicing these youth.

SOURCE: Fassett, 2012.

Family Justice Centers (FJCs)

FJCs are a model of multisector and interagency collaboration similar to CACs. In an FJC, a multidisciplinary team of professionals is collocated and works together to provide coordinated services to victims of domestic violence. The first FJC opened in 2002 in San Diego (Gwinn et al., 2007). Since then, about 80 have been created (Family Justice Center Alliance, 2013). FJCs are designed to “provide one place where victims can go to talk to an advocate, plan for their safety, interview with a police officer, meet with a prosecutor, receive medical assistance, receive information on shelter, and get help with transportation” (Family Justice Center Alliance, 2013). As described in Chapters 3 and 6, commonalities between commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking and domestic violence include similar power and control dynamics and the need for safe shelter.

Sexual Assault Response Teams

SARTs (sometimes referred to as sexual assault interagency councils [SAICs], sexual assault multidisciplinary action response teams [SMARTs], or coordinated community response [CCR] teams) are another notable model of multisector collaboration. SARTs are community-based interventions that provide comprehensive care to victims of sexual assault and coordinate the legal, medical, mental health, and advocacy response (Greeson and Campbell, 2013). SARTs represent a shift from a case focus to a victim/survivor focus that emphasizes the centrality of victims/survivors and their needs to the overall process of dealing with sexual assault (Latimer, 2012; National Sexual Violence Resource Center, 2006). SARTs engage in a variety of activities, including, among others, conducting multidisciplinary training, providing direct support and advocacy to victims and survivors, developing protocols and policies for responding to cases, conducting case review to coordinate the response to cases, and educating the public about sexual violence and resources available to survivors (Office of Justice Programs, 2011; Zajac, 2009).

Evaluations of the impact and effectiveness of SARTs (and similar multidisciplinary efforts to respond to sexual assault, as well as family violence) are scarce. For example, fewer than a quarter of respondents to one recent national survey of SARTs (23 percent, n = 54) stated that their SART and its activities had been evaluated (Zajac, 2009). The evaluations reported consisted primarily of gauging victims’ satisfaction with services, the reliability of evidence collection, and satisfaction with sexual assault training. Despite the limited evidence on their effectiveness, however, SARTs, like FJCs, are examples of multisector collaboration in similar and related areas of victimization that may offer valuable insights and support for the development of multisector and interagency responses to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors.

MULTISECTOR AND INTERAGENCY EFORTS TO

ADDRESS COMMERCIAL SEXUAL EXPLOITATION

AND SEX TRAFFICKING OF MINORS

As noted throughout this report, since passage of the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) in 2000, the federal government has made significant investments in efforts to prevent and address the commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors, efforts that include multisector and interagency collaboration. Some of these efforts—particularly those focused primarily on collaboration among federal, state, and local law enforcement—have been described in earlier chapters. In addition, the federal government engages in a number of interagency efforts focused mainly on

international human trafficking (e.g., U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and the Office of Refugee Resettlement). In accordance with the committee’s charge, this section reviews multisector and interagency efforts as they relate to domestic human trafficking and specifically, to the extent possible, to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States.

Task Forces Funded by the Department of Justice

The Department of Justice’s (DOJ’s) anti-human trafficking task forces are one federally supported model of interagency and multisector collaboration to prevent and address commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States. While the committee recognizes that task forces exist at the federal, state, and local levels, those involving federal agencies are doing some of the most visible work. This section describes some of the major DOJ task forces focused on commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States.

Cook County Human Trafficking Task Force

Multisector and interagency collaboration is a key feature of the approach of Cook County (Illinois) to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. Formal collaboration among sectors and agencies occurs through the federally funded Cook County Human Trafficking Task Force, which is co-led by the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office; the U.S. Attorney’s Office; the Northern District of Illinois; and two local NGOs, the Salvation Army’s STOP-IT Program and the International Organization for Adolescents (Greene, 2012).

Members of this task force employ a mix of strategies in the pursuit of vigorous prosecution of exploiters, traffickers, and purchasers and the provision of comprehensive victim and support services for victims and survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking. For example, the STOP-IT Program has an office embedded at the State’s Attorney’s Office, where service providers are able to assist victims as soon as they come to the attention of law enforcement (Knowles-Wirsing, 2012). In addition, the U.S. Attorney’s Office convenes a subgroup of the task force each month. In these sessions, representatives of federal and local prosecutors, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the county sheriff, local police, and the Internal Revenue Service, among others, meet to discuss openly every case of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors that is under investigation or assigned to a prosecutor (Nasser, 2012).

Another aspect of Cook County’s multisector approach to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors is that the work of

both law enforcement and service providers is victim centered (Greene, 2012; Knowles-Wirsing, 2012). During the committee’s Chicago site visit, for example, representatives of the State’s and U.S. Attorney’s Offices asserted that investigations should be “victim-centered, but not victim-built” (Nasser, 2012), meaning that they help victims obtain services and do not rely on a victim’s testimony alone to build a case (see also Chapter 5). Examples of corroborative evidence have included wiretaps, victims’ journals, victims’ tattoos, evidence of traffic stops where a trafficker was stopped with victims, hotel records, and medical records (Greene, 2012). Service providers tailor services (including medical, mental health, sexual health, and case management) for each victim depending on that individual’s needs (Knowles-Wirsing, 2012).

Finally, because the Illinois Safe Children Act gives the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS) jurisdiction over all minors arrested for prostitution, the task force has worked with DCFS to build systems that can accept and process reports of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors and deliver appropriate services to victims (Walts et al., 2011). This work has involved convening groups of key leaders within DCFS to create a comprehensive blueprint for how DCFS should manage cases of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors, training DCFS staff to identify these crimes, providing technical assistance, and connecting DCFS with service providers in the community (Walts et al., 2011).

Office of Justice Programs Task Forces

DOJ’s Office of Justice Programs, through the Bureau of Justice Assistance and the Office for Victims of Crime (OVC), funds anti-human trafficking task forces to assist and support victims of human trafficking. To date, the Office of Justice Programs has funded 42 jurisdictions and 36 victim and support service providers to form such task forces (BJA, 2013). As noted earlier, Chapter 5 includes a review of anti-human trafficking task forces that are primarily in the law enforcement domain.

The Bureau of Justice Assistance and OVC work jointly to provide funding and support to multidisciplinary anti-human trafficking task forces through the Enhanced Collaborative Model to Combat Human Trafficking program (OVC and BJA, 2013). Each task force comprises a state, local, or tribal law enforcement agency (funded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance) and a victim service organization (funded by OVC) (OVC and BJA, 2013). Members of the task force work collaboratively, across sectors, and in close coordination with the local U.S. Attorney’s Office to strengthen investigations and prosecutions of exploiters and traffickers and to coordinate the delivery of comprehensive services to human trafficking victims identified

in their jurisdiction (OVC and BJA, 2013). (OVC’s comprehensive service model is described below.)

Varying degrees of collaboration take place among the members of task forces funded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance and OVC. Some of the task forces have adopted an all-comers approach to increase opportunities for collaboration and expand the reach of their activities. For example, membership in the Washington, DC, Metropolitan Police Task Force is “open to any D.C. metropolitan area law enforcement agency or non-governmental organization involved in anti-trafficking activities” (U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia, 2013). As a result, the task force has nearly 30 members, including the DC Office of the Attorney General, the Criminal Section within DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Department of Labor, Boat People SOS, the Asian Pacific American Legal Resource Center, Innocents at Risk, Polaris Project, Helping Individual Prostitutes Survive (HIPS), and Restoration Ministries. Additional research is needed to better understand and evaluate the level of collaboration and cooperation that results from these federally funded community task forces.

Efforts Funded by the Office for Victims of Crimes

Multisector and interagency work on human trafficking through OVC has evolved over the last decade. In 2003, OVC awarded its first grants to organizations and agencies working with foreign national victims and survivors of human trafficking (including labor and sex trafficking). This work was followed by awards to law enforcement task forces, awards to agencies and organizations working with domestic minor victims and survivors, and finally awards to agencies and organizations providing comprehensive services and specialized mental health and legal services to all victims/survivors of human trafficking (OVC and BJA, 2011).

OVC’s comprehensive service model for victims of human trafficking includes

• wraparound services (i.e., support services tailored to the needs of individual victims/survivors);

• emergency and ongoing assistance;

• trauma-informed, culturally competent services; and

• support and advocacy during interactions with law enforcement.

The model includes the following specific services:

• intake and eligibility assessment,

• shelter/housing and sustenance,

• dental care,

• legal assistance,

• literacy education and job training,

• 24-hour response to client emergencies,

• intensive case management,

• medical care,

• mental health care,

• interpretation/translation services,

• victim advocacy, and

• transportation.

Implementing OVC’s comprehensive service model requires significant and sustained efforts among agencies and across sectors.

In 2009, OVC funded three pilot sites for its Domestic Minor Demonstration Project (OVC, 2013). Three service providers—Safe Horizon in New York, Standing Against Global Exploitation (SAGE) in San Francisco, and the Salvation Army’s Chicago Metropolitan Division—were selected to develop, enhance, or expand the community response to domestic minor victims/survivors of all forms of human trafficking. According to DOJ, an independent evaluation of the demonstration project is ongoing (OVC, 2013).

Interagency Task Force to Monitor and Combat Trafficking

At the highest level of federal involvement, the reauthorization of the TVPA, the William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008 (TVPRA), requires the continued functioning of a task force focused on human trafficking.3 The President’s Interagency Task Force to Monitor and Combat Trafficking is a cabinet-level task force that coordinates federal efforts to address human trafficking. Task force members include the U.S. Department of State (the Secretary of State serves as chair), the administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development, the attorney general, the secretary of labor, the secretary of health and human services, the director of the Central Intelligence Agency, the director of national intelligence, the secretary of defense, the secretary of homeland security, the secretary of education, and such other officials as may be designated by the President (U.S. Department of State, 2012).

The task force, which meets annually, is charged with measuring and evaluating progress in the United States and abroad on the prevention of human trafficking, the protection of victims and survivors, and the pros-

__________________________

3William Wilberforce Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2008, Public Law 110-457, 122 Stat. 5044.

ecution of traffickers. The task force also is responsible for ensuring that data collection and research on human trafficking are conducted by all task force member agencies.

In April 2013, the President’s Interagency Task Force to Monitor and Combat Trafficking released a federal strategic action plan on services for victims of human trafficking in the United States (President’s Interagency Task Force to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, 2013).4 This 5-year plan calls for collaboration across federal agencies to improve the availability and delivery of effective and comprehensive services to all victims of human trafficking. Among its goals, the plan emphasizes the need for increased coordination and collaboration at the national, state, tribal, and local levels, as well as the need to strengthen partnerships with nongovernmental stakeholders. While this plan lays the foundation for extensive multisector and interagency collaboration, it will be important to track the extent to which this collaboration occurs in the plan’s implementation over time.

Partnerships in the Trafficking Victims Protection

Reauthorization Act of 2013

On March 8, 2013, President Obama signed the TVPRA of 2013. The act includes a mandate that the federal government “promote, build, and sustain partnerships” between the U.S. government and “private entities, including foundations, universities, corporations, community based organizations, and other nongovernmental organizations to ensure that . . . United States citizens do not use any item, product, or material produced or extracted with the use and labor from victims of severe forms of trafficking; and . . . such entities do not contribute to trafficking in persons involving sexual exploitation.”5 Although it is too early to evaluate the impact of this new requirement, it provides a basis for expanding and strengthening efforts to develop multisector collaboration among public and private entities to prevent, identify, and respond to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States.

State and Local Efforts

State and local efforts to effect multisector and interagency collaboration to address commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of

__________________________

4At the time this report was written, the Federal Strategic Action Plan was open for public comments. The final plan may be revised to reflect input from the public comment period.

5Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 (VAWA) ![]() 1202 (2013) (the TVPA Reauthorization of 2013 was attached as an amendment to VAWA).

1202 (2013) (the TVPA Reauthorization of 2013 was attached as an amendment to VAWA).

minors are prosecution based, county based, and state based. In addition, a number of law enforcement agencies have implemented anti-human trafficking task forces and working groups among interested parties in local jurisdictions to address commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors, as well as human trafficking more broadly. Descriptions of such law enforcement efforts can be found in Chapter 5.

Prosecution-Based Efforts

The Alameda County District Attorney’s Office has developed and implemented H.E.A.T. (Human Exploitation and Trafficking) Watch, a “multidisciplinary, multisystem” approach to responding to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors (Alameda County District Attorney’s Office, 2012). The program, which brings together individuals and agencies from law enforcement, health care, advocacy, victim and support services, the courts, probation agencies, the commercial sector, and the community, has two primary goals: (1) to ensure the safety of victims/survivors and (2) to pursue accountability for exploiters/traffickers. Strategies employed by H.E.A.T. Watch include, among others, stimulating community engagement, coordinating training and information sharing, and coordinating the delivery of victim and support services, among others (Alameda County District Attorney’s Office, 2012).

One of the key features of the H.E.A.T. Watch program is its strong focus on prosecution of exploiters and traffickers. To that end, the district attorney’s office prosecutes as felons individuals who “solicit children under the age of 14 for sex, those who lure children into the commercial sex trade, and enforcers, who act as security guards and conspire to exploit victims for financial gain” (Alameda County District Attorney’s Office, 2010). The district attorney’s H.E.A.T. Unit prosecutes exploiters and traffickers under the California Human Trafficking Statute, as well as laws on pimping and pandering, sexual assault, kidnapping, and burglary. Since its inception in 2006, the H.E.A.T. Unit has charged 237 defendants and convicted 160 offenders of crimes related to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking. In addition, the district attorney’s office recognizes and treats children and adolescents who are exploited and trafficked as victims of child abuse, not criminals (see the discussion of this issue in Chapter 5) (Alameda County District Attorney’s Office, 2012), thus ensuring that the focus of prosecutorial efforts remains on traffickers and exploiters.

In addition to its focus on prosecution, the H.E.A.T. Watch program uses a multisector approach to coordinate the delivery of support services to minors who are at risk or who are victims/survivors of commercial sexual exploitation or sex trafficking (Alameda County District Attorney’s Office, 2012). For example, H.E.A.T. Watch uses multidisciplinary case review

(modeled on the multidisciplinary team approach) to create emergency and long-term safety plans for these youth (Alameda County District Attorney’s Office, 2012). Referrals for case review are made by law enforcement, prosecutors, probation, and social service organizations that have come into contact with these children and adolescents. This approach enables members of the multidisciplinary team to share confidential information with agencies that can assist youth in need of services and support.

County-Based Efforts

Multnomah County, Oregon In 2008, Multnomah County, Oregon, initiated a coordinated multisector response to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. This work originated as a partnership between the Sexual Assault Resources Center, a local nonprofit that serves survivors of sexual assault, and two law enforcement agencies, the Portland Police Bureau and the FBI (Baker and Nelson, 2012). Together, they conducted a needs assessment for victims and survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in Multnomah County. This work helped identify areas of need and essential community partners and laid the foundation for the Community Response to Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children (Baker and Nelson, 2012).

With additional funding from local, state, and federal sources, Multnomah County formalized and enhanced its response to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors (Multnomah County, 2012). Enhancements included hiring staff, establishing a steering committee and work groups, engaging community partners, and aggressively training professionals and groups across systems to identify and assist minors who are at risk of or victims/survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking (Baker and Nelson, 2012). Specific work groups focus on legislation, assistance for victims and survivors, law enforcement practices (e.g., arrests, investigation, and prosecution of exploiters and traffickers), and physical and mental health care. Steering committee members include law enforcement; the district attorney’s office; the Departments of Health, Community Justice, and Human Services; survivors; and nongovernmental service providers (Multnomah County, 2012).

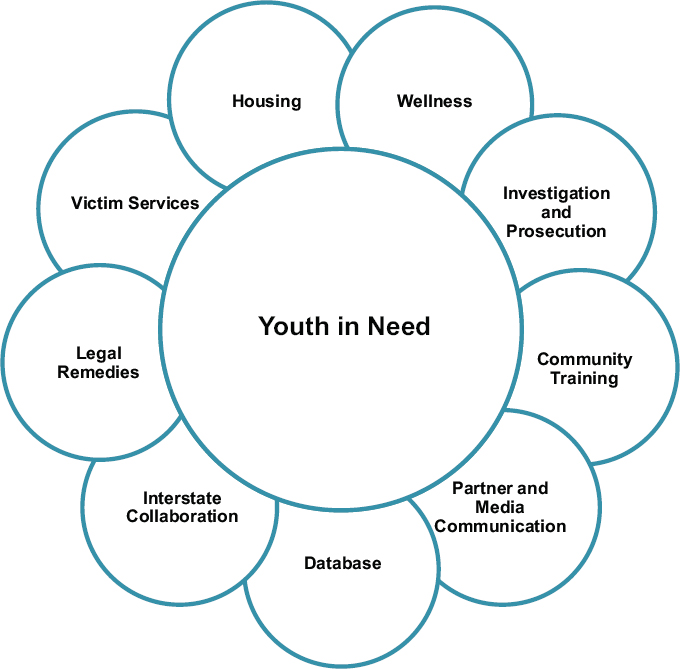

Multnomah County uses several strategies to ensure collaboration across agencies and among various systems. For example, the county created a special unit within the state child welfare agency for victims and survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking (Multnomah County, 2012). In addition, the county uses a multidisciplinary team approach to address cases of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors (Baker and Nelson, 2012). Finally, the county has created a vision for a multisector approach to “youth in need”—children and ado-

FIGURE 10-1 Components of a multisector response to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in Multnomah County, Oregon.

lescents who are at risk of or are victims/survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking (see Figure 10-1).

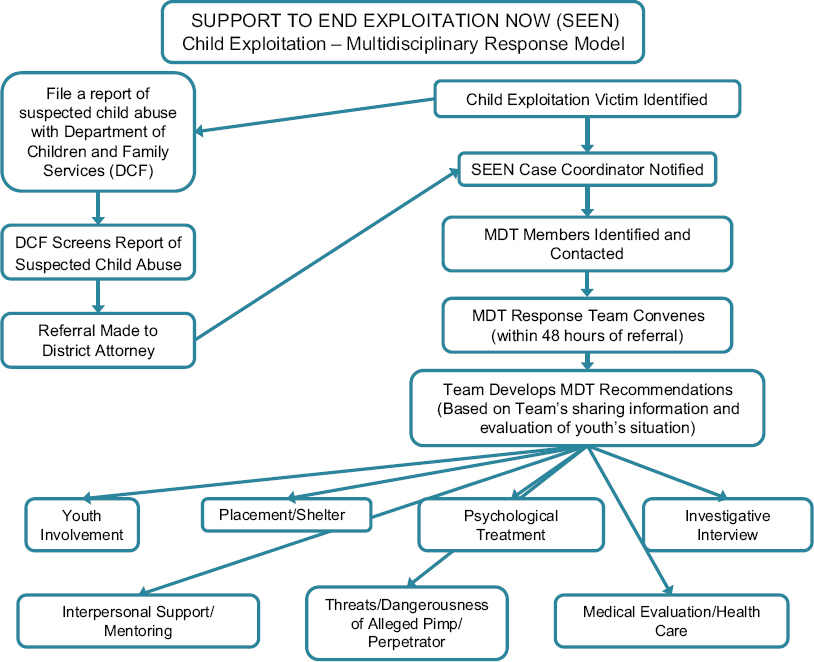

Suffolk County, Massachusetts In Suffolk County, Massachusetts, more than 35 public and private agencies participate in the Support to End Exploitation Now (SEEN) Coalition. SEEN represents a multisector, coordinated approach to identifying high-risk and sexually exploited minors. The SEEN approach includes three components: (1) cross-system collaboration, (2) a trauma-informed continuum of care, and (3) training for professionals who work with children and adolescents. The SEEN Coalition’s goals are “to provide effective coordinated interventions for young people involved with CSEC [commercial sexual exploitation of children] and to enhance

policy and programming to improve the system response to CSEC” (Piening and Cross, 2012, p. 8).

To facilitate collaboration and communication among coalition members, SEEN established formal relationships and protocols, including a steering committee and advisory group, multidisciplinary teams of professionals, and a case coordinator who serves as the central point of contact for all reported victims of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking. Figure 10-2 shows the SEEN multidisciplinary team protocol. In addition, SEEN maintains a database of individuals who have received services under its auspices. Activities carried out by the coalition are supported by safe harbor legislation (see Chapter 5) in the State of Massachusetts (Piening and Cross, 2012).

According to a recent report, since its inception in 2005, the SEEN Coalition has served 482 high-risk and commercially sexually exploited girls; the median age of SEEN clients is 15, and a majority (67 percent) are

FIGURE 10-2 A multidisciplinary response model for addressing child exploitation in Suffolk County, Massachusetts.

NOTE: MDT = multidisciplinary team.

girls of color. Sixty-two percent (n = 301) have run away from home, and 70 percent (n = 336) have current or prior involvement with child protective services (Piening and Cross, 2012).

State-Based Efforts

Washington State In November 2012, Washington State released a statewide model Domestic Minor Sex Trafficking protocol for responding to cases of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors (Bridge et al., 2012). The protocol was developed with input from nearly 200 stakeholders throughout Washington State, including judges, juvenile court representatives, law enforcement representatives, representatives of the Department of Social and Health Services’ Children’s Administration, service providers, and community advocates, among others (Bridge et al., 2012). The Center for Children & Youth Justice, a Seattle-based nonprofit organization, will assist in the implementation of the statewide protocol by training agencies that work with victims and survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking, establishing structures for revising and improving the protocol, monitoring emerging best practices, collecting data, and proposing needed statewide policies to address commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors (Bridge et al., 2012).

The overall goals of the Washington State protocol are to foster collaboration and coordination among agencies, to improve identification of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors, to provide services to victims and survivors, to hold exploiters accountable, and to work toward ending commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in Washington State (Bridge et al., 2012). The protocol calls for use of a victim-centered approach by law enforcement, the courts, victim advocacy organizations, youth service agencies, and other youth-serving professionals to ensure that victims of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking are recognized and treated as crime victims rather than criminals.

The Washington State protocol encourages multisector collaboration through state, regional, and local efforts to address the commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. For example, the protocol calls for the use of multidisciplinary teams to provide immediate consultation on cases of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors as they arise and to participate in meetings to share information and collaborate in the management of each ongoing case. In addition, the protocol calls for the creation of local and regional task forces of stakeholders who serve victims and survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking to promote a coordinated community response and adapt the model protocol to their jurisdiction. Finally, the protocol calls for a Statewide CSEC

(Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children) Coordinating Committee that will meet annually to receive reports from the local/regional task forces on data collection efforts, community response practices and results, and recommendations for policy and/or legislative changes.

The Washington State effort, although not yet implemented, is noteworthy for the degree of multisector collaboration involved in the development of the protocol, as well as for the extent to which it calls for continued multisector collaboration at the local and regional levels throughout the state.

State of Georgia As described in Chapter 6, the Georgia Care Connection is a statewide effort established by the Georgia Governor’s Office for Children and Families. Its purpose is to serve as “a central hub” for victims/survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking and for professionals (e.g., law enforcement personnel, school personnel, child welfare professionals, health care providers) seeking assistance for them (GCCO, 2013).

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

Despite the multisector and interagency efforts described in the preceding sections, a number of factors inhibit collaboration across sectors and among agencies. Through testimony during its workshops and site visits and the limited information in the published literature, the committee identified common challenges faced by agencies and other organizations seeking to engage in collaborative efforts to respond to the commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. For example, one frequently cited barrier to such collaboration is the lack of a shared framework for understanding the experience of victims. The committee heard from workshop presenters and site visit participants that collaboration was most successful when groups had a shared understanding and a shared framework (Alameda County District Attorney’s Office, 2012; Baker and Nelson, 2012; Goldblatt, 2012; Greene, 2012). The differences in the personnel, principles, practices, and approaches of the different systems noted earlier make this agreement all the more critical. This section provides an overview of the factors that inhibit and support collaboration and identifies opportunities to advance collaboration across sectors and among agencies.

Lack of Training

As noted in each of the sector-specific chapters in this report, one barrier to effective prevention, identification, and intervention for children and adolescents who are at risk for or are victims of commercial sexual exploi-

tation and sex trafficking is a lack of training. Lack of training assumes added significance when a problem requires that a range of sectors work together. It is critical for professionals in all agencies and sectors that serve youth to be adequately prepared to identify and assist victims/survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking, and training is an essential element of such preparation.

While unable to assess current levels of training across sectors and systems that serve children and adolescents, the committee learned that a lack of training—and of availability of training—remains a challenge to adequately addressing the commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States. Current multisector and interagency collaborations present an opportunity to provide training across systems and agencies. Many of the efforts described in this chapter, such as Georgia Care Connection and the Multnomah County community response, use cross-sector training to enhance partnerships and conduct retraining to address turnover within systems and organizations. However, more work is needed to bring these efforts to scale and to ensure that training is evaluated and informed by evidence.

Lack of Shared Frameworks, Data Systems, and Incentives

Another barrier to multisector and interagency collaboration is the lack of a shared understanding of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors, particularly with respect to victims and survivors. As noted throughout this report, victims and survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking may be perceived and treated differently by different sectors and systems. They may be viewed as “bad kids,” uncooperative youth, and criminals by some and as youth in need of assistance, victims, and survivors by others. These perceptions are influenced by such factors as local laws and practices (as described in Chapter 4), levels of awareness and biases (as described in Chapter 7), and the presence of task forces (as described in Chapter 5). Having a shared understanding of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors is particularly important when agencies and sectors collaborate. Workshop presenters and site visit participants stressed that until the various sectors and systems have a shared understanding of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors, work to address these problems will be impeded (Baker and Nelson, 2012).

Concerns about privacy, confidentiality, and data sharing also can inhibit collaboration across sectors and among agencies and systems, such as health care, juvenile justice, law enforcement, schools, and child protective services. As noted in Chapter 4, certain laws (i.e., the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act [FERPA] and the Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act [HIPAA]) regulate how information is shared and with whom. In addition, the lack of integrated data systems can make sharing data and coordinating services difficult. For example, few municipalities or states have data systems that share or link data from different systems to facilitate effective communication and case management. In many cases, concerns about confidentiality, data sharing, and potential legal liability, whether perceived or real, serve as barriers to effective coordination among the multiple systems and sectors addressing commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States.

Finally, the lack of explicit incentives for collaboration across sectors and among agencies and systems is another barrier to addressing commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States effectively. Multisector approaches may require that professionals and systems accept alternative frameworks and new practices, undergo additional and ongoing training, or engage in increased interaction with new partners, which in turn may require more work. Without clear incentives for collaboration, individuals may be resistant to such additional work, regardless of its effectiveness. Participants in the multisector and interagency approaches described in this chapter have acknowledged the need to address the perceived or real burden of additional work involved in such collaborative efforts. One strategy for incentivizing collaboration, used by Multonomah County, Alameda County, and Suffolk County, is to create paid positions and to institutionalize collaboration through formal arrangements (Alameda County District Attorney’s Office, 2012; Baker and Nelson, 2012; Goldblatt, 2012).

Stakeholders can draw valuable lessons from collaborations among child protective services, law enforcement, juvenile justice, health care, and other sectors that have required agencies and systems to create shared frameworks, to share data, and to devise incentives for collaboration. CACs, FJCs, and SARTs (described earlier in this chapter) are three models that may provide insights in this regard.

Lack of Sustained Funding

Lack of funding in both the short and long terms is often a barrier to sustaining multisector collaborations and partnerships. The presence of funding can serve as the catalyst to encourage individuals from different sectors to start working together, and also can promote the evaluation of efforts. Conversely, in the absence of sustained funding, multisector efforts may be unable to continue. One strategy described in this chapter for working with the limited funds available to support multisector approaches to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States is to adapt or expand models used to address related and overlapping

issues. CACs, such as Kristi House, or multidisciplinary SARTs, such as those used by Multnomah County, are noteworthy examples of multisector approaches that have been adapted and expanded to meet the needs of victims/survivors of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors.

At the same time, ample funding in the absence of political will or strong leadership is unlikely to establish lasting multisector collaboration. Conversely, with political will and/or strong leadership, even limited resources can be leveraged to accomplish beneficial changes that can then serve as the basis for continued progress and justification for increased resources in the future. The Dallas High-Risk Victims Working Group, described earlier in this chapter (see Box 10-1), is an example of a multisector effort that started without any funding, but was supported by the shared commitment of service providers, law enforcement, government agencies, and others in the community (Fassett, 2012).

While the dedication of an influential leader is often critical to initiating and maintaining focus on a problem such as commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors, a commitment to multisector approaches needs to be institutionalized to ensure that a continued focus on the problem is not dependent on the passion and personality of a strong leader. Widespread community awareness and acknowledgment of the seriousness of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors are pivotal to ensuring that adequate attention and resources are devoted to developing solutions and to overcoming the challenges inherent in multisector and interagency coordination.

Barriers to Communication

Another barrier to multisector collaboration is the challenges of communication among individuals in different sectors. Different organizational cultures within sectors often entail different terminologies, definitions, and world views. Communication plays a key role in successful multisector collaboration. For example, sharing information about cases of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors across sectors and among agencies and systems requires communication and a shared understanding of the problem and solutions (Alameda County District Attorney’s Office, 2012; Baker and Nelson, 2012; Goldblatt, 2012; Littrell, 2012). Regular meetings of groups and task forces can create a sense of shared purpose and community among participants. Many factors are involved in facilitating the ideal communication environment for collaborators, including who is able to speak and when, and whether the ideas of certain individuals or groups are accepted or perceived as more or less valid than those of others. The highly coordinated multidisciplinary case review activities of SEEN in

Suffolk County and H.E.A.T. Watch in Alameda County, discussed earlier in this chapter, are noteworthy examples of how multiple agencies and sectors have made frequent communication an integral part of their overall approach to addressing commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors.

Foot and colleagues (Foot and Toft, 2010; Foot and Vanek, 2012; Stoll et al., 2012) studied the communication contexts that engender collaboration among individuals and groups that work on antitrafficking efforts. Stoll and colleagues (2012) demonstrate the potential for information and communication technology to provide a platform for communication and connectedness to support the building of multisector collaborations. Connectedness among antitrafficking networks was instantiated by exchanging contact information and objectives, enabling connections through coordinating meetings, and reinforcing connections through follow-up meetings and events (Stoll et al., 2012). Caution is warranted, however, as information and communication technology can either strengthen connectedness or result in miscommunication or mishandling of information. While lessons can be drawn from this research and efforts in Suffolk County and Alameda County, among others, additional research is needed to advance understanding of communication strategies for multisector collaboration.

Limited Resources for Rural and Tribal Communities

Commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors do not occur exclusively in urban areas. However, most of the infrastructure designed to respond to these crimes is located in cities. For example, most task forces and service providers are located in urban areas (BJA and OVC, 2012). As a result, most rural areas have few resources with which to respond to these crimes. Similarly, while some evidence suggests high rates of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of American Indian and Alaska Native adolescents (Koepplin and Pierce, 2009; Pierce, 2012), few resources currently are dedicated to addressing these crimes among these populations.

Despite the general lack of resources for rural areas and tribal communities, the need for additional attention to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors among these populations is increasingly being acknowledged (Pierce, 2012; President’s Interagency Task Force to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons, 2013). However, special challenges and barriers may be entailed in preventing, identifying, and responding to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in rural areas and in tribal communities. As limited as awareness of and training on these issues are nationally, for example, research indicates that levels of awareness and training are even lower in rural areas. A study on the

identification of victims and potential victims of human trafficking found that, among a random sample of 60 counties across the United States, law enforcement personnel in rural counties often lacked awareness of and/or training in human trafficking (Newton et al., 2008). The authors found that service providers in larger metropolitan counties reported recognizing human trafficking more often than service providers in rural and suburban counties. Finally, the authors found that service providers in rural areas were especially lacking in training in human trafficking (Newton et al., 2008). The committee spoke with several service providers that are making an effort to expand their services to outlying parts of their state, but nearly all noted challenges to providing services to rural areas, including long distances for staff travel, the lack of reliable transportation for victims and survivors to reach service providers, and few housing options (Carlson, 2012; Goldblatt, 2012).

In its examination of the evidence, the committee was able to identify just a handful of task force and multisector efforts focused exclusively on human trafficking in rural communities and among Native populations. One example of a multisector approach to addressing commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of Native Americans is the Phoenix Project in Minnesota, a collaboration between the Minnesota Indian Women’s Resource Center and the Division of Indian Work, the Minneapolis Police Department, and Hennepin County Juvenile Probation. Through this effort, these organizations have developed a formal process for referring Native girls who are suspected of being commercially sexually exploited or trafficked for sex to culturally based, gender-focused services (Pierce, 2012). Specifically, if victimization is suspected or disclosed to an outreach worker or law enforcement personnel, the victim is referred to the Minnesota Indian Women’s Resource Center for services, including educational programs on healthy relationships, support groups, and case management (Pierce, 2012). In addition, the Minnesota Indian Women’s Resource Center advocates for program participants with child protective services and schools and provides referrals to other programs and services (i.e., basic needs, shelter) as needed (Pierce, 2012).

More research is needed to advance understanding of the extent of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in rural areas and tribal communities, as well as the potential for multisector collaboration to address these problems among these populations.

Multisector Information-Sharing Tools

As noted above, information-sharing tools can offer a beneficial opportunity for multisector collaboration. In the last decade, such tools have been developed for the law enforcement sector as the U.S. government has sought

to improve and centralize information- and intelligence-sharing capabilities among various government agencies. One example is the Department of Homeland Security’s coordinated national network fusion centers, which centralize information and data collection on potential terrorist threats at the national, state, and local levels (Department of Homeland Security, 2013). Another initiative is the Regional Information Sharing Systems (RISS) Program, a congressionally funded program that allows access to information and data for law enforcement and criminal justice professionals. These systems increasingly are being used to investigate case of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States.

While direct access to these systems is limited to law enforcement, they have the potential to serve as models for information-sharing platforms across sectors dealing with domestic commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. A movement is occurring toward building technological systems and platforms that enable real-time data collection and analysis to facilitate rapid response to vulnerable and at-risk minors (Latonero, 2011). One challenge to developing such information-sharing technologies is that the process itself requires multisector collaboration. Government, the private sector, social services, and the research community need to be involved in such a development project. The Obama Administration has stated its intent to use technology to respond to human trafficking in the United States (White House Office of the Press Secretary, 2012), as have private-sector technology firms such as Microsoft (Microsoft Research and Microsoft Digital Crimes Unit, 2012) and Google (Ungerleider, 2012) and nongovernmental organizations such as Polaris Project (Latonero, 2011). How these entities can ultimately work together to develop shared information environments for multisector collaboration to address commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States remains to be seen.

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

While this chapter has provided examples of a range of current and emerging models of multisector collaboration to address commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States, the committee does not advocate a one-size-fits-all approach and acknowledges a variety of formulations, strategies, and mechanisms whereby collaboration and partnerships may occur. The committee’s review of the literature and its careful consideration of expert testimony revealed several themes related to multisector and interagency approaches to preventing, identifying, and responding to commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States. This chapter has highlighted a range of noteworthy and emerging efforts and drawn lessons from multisector approaches in related

fields of practice. However, the committee reminds readers that evaluation of these and future efforts is a crucial need. In addition, the committee formulated the following findings and conclusions:

| 10-1 | Multisector and interagency collaboration is necessary to respond adequately to the multifaceted nature of commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. |

| 10-2 | Existing multisector and interagency approaches to child mal-treatment, sexual assault, and domestic violence can serve as models for approaches to address commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors. |

| 10-3 | Federally funded task forces are highly visible multisector approaches, yet have not yet been evaluated for effectiveness. |

| 10-4 | Many of the same challenges that exist in individual sectors and systems (e.g., communication, funding, information sharing) arise within multisector and interagency approaches and need to be resolved. |

| 10-5 | Sustained funding, strong leadership, and formal arrangements are important drivers for the institutionalization of multisector and interagency approaches. |

| 10-6 | Broad-based multisector and interagency collaborative approaches that are victim centered and tailored to the unique needs and circumstances of victims/survivors and their communities appear to hold the most promise for positively impacting commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking of minors in the United States. |

REFERENCES

Alameda County District Attorney’s Office. 2010. District attorney’s office unveils H.E.A.T. Watch. http://www.alcoda.org/news/archives/2010/jan/office_unveils_heat_watch (accessed July 10, 2013).

Alameda County District Attorney’s Office. 2012. H.E.A.T. Watch program blueprint. http://www.heat-watch.org/heat_watch (accessed September 13, 2012).

Alexander, R. C. 1993. To team or not to team: Approaches to child abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 2:95-97.

Armstrong, R., J. Doyle, C. Lamb, and E. Waters. 2006. Multi-sectoral health promotion and public health: The role of evidence. Journal of Public Health 28(2):168-172.

Baker, J., and E. Nelson. 2012. Workshop presentation to the Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States, on Multi-Disciplinary Responses, May 9, 2012, San Francisco, CA.

BJA (Bureau of Justice Assistance). 2013. Anti-Human Trafficking Task Force Initiative. https://www.bja.gov/ProgramDetails.aspx?Program_ID=51 (accessed July 5, 2013).

BJA and OVC (Office for Victims of Crime). 2012. BJA/OVC human trafficking task forces. https://www.bja.gov/Programs/40HTTF.pdf (accessed April 30, 2013).

Bridge, B. J., N. Oakley, L. Briner, and B. Graef. 2012. Washington State model protocol for commercially sexually exploited children. Seattle, WA: Center for Children and Youth Justice.

Buffardi, A. L, R. Cabello and Garcia, P. J. 2012. Toward greater inclusion: Lessons from Peru in confronting challenges of multi-sector collaboration. Pan American Journal of Public Health 32(3):245-250.

Carlson, K. 2012. Site visit presentation to the Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States, on Roxbury Youthworks, Gaining Independence for Tomorrow (GIFT) Program, March 23, 2012, Boston, MA.

Clawson, H. J., N. Dutch, and M. Cummings. 2006. Law enforcement response to human trafficking and the implications for victims: Current practices and lessons learned. Fairfax, VA: Caliber.

Cross, T. P., L. M. Jones, W. A. Walsh, M. Simone, D. J. Kolko, J. Szczepanski, T. Lippert, K. Davison, A. Cryns, P. Sosnowski, A. Shadoin, and S. Magnuson. 2008. Evaluating children’s advocacy centers’ response to child sexual abuse. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. http://www.unh.edu/ccrc/pdf/CV136.pdf (accessed April 30, 2013).

Department of Homeland Security. 2013. State and major urban area fusion centers national network of fusion centers. http://www.dhs.gov/state-and-major-urban-area-fusion-centers (accessed April 27, 2013).

Faller, K. C., and V. J. Palusci. 2007. Children’s advocacy centers: Do they lead to positive case outcomes? Child Abuse and Neglect 31(10):1021-1029.

Family Justice Center Alliance. 2013. What is a family justice center? http://familyjusticecenter.com/home.html (accessed April 27, 2013).

Fassett, B. 2012. Workshop presentation to the Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States, Dallas Police Department’s Approach to CSEC, February 29, 2012, Washington, DC.

Foot, K., and A. Toft. 2010. Collaborating against human trafficking. In Second Annual Interdisciplinary Conference on Human Trafficking. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska.

Foot, K., and J. Vanek. 2012. Toward constructive engagement between local law enforcement and mobilization and advocacy nongovernmental organizations about human trafficking: Recommendations for law enforcement executives. Law Enforcement Executive Forum 12(1):1-12.

GCCO (Georgia Care Connection Office). 2013. Georgia Care Connection. http://www.georgiacareconnection.com (accessed January 6, 2013).

Goldblatt, L. G. 2012. Site visit presentation to the Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States, on My Life, My Choice, March 23, 2012, Boston, MA.

Gonzales, A., M. Guillén, and E. Collins. 2011. A multidisciplinary approach is the key to combating child sex trafficking. Police Chief 78:26-36.

Greene, J. 2012. Site visit presentation to the Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States, on Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office, Human Trafficking Task Force, July 11, 2012, Chicago, IL.

Greeson, M. R., and R. Campbell. 2013. Sexual Assault Response Teams (SARTs): An empirical review of their effectiveness and challenges to successful implementation. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse 14(2):83-95.

Gwinn, C., G. Strack, S. Adams, R. Lovelace, and D. Norman. 2007. The Family Justice Center Collaborative Model. Saint Louis University Public Law Review 79.

Hochstadt, N. J., and N. J. Harwicke. 1985. How effective is the multidisciplinary approach? A follow-up study. Child Abuse and Neglect 9(3):365-372.

IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2002. Primary care and public health: Exploring integration to improve population health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Knowles-Wirsing, E. 2012. Workshop presentation to the Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States, on Salvation Army STOP-IT, July 11, 2012, Chicago, IL.

Koepplin, S., and A. Pierce. 2009. Commercial sexual exploitation of American Indian women and girls. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska.

Kristi House. 2012. Commercial sexual exploitation. http://www.kristihouse.org/commercial-sexual-exploitation (accessed on January 4, 2013).

Latimer, D. 2012. Site visit presentation to the Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States, Mount Sinai Sexual Assault and Violence Intervention (SAVI) Program, September 12, 2012, New York.

Latonero, M. 2011. Human trafficking online: The role of social networking sites and online classifieds. Los Angeles, CA: University of Southern California, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Littrell, J. 2012. Workshop presentation to the Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States, on the Grossmont Union High School District Services and Programs, May 9, 2012, San Francisco, CA.

Microsoft Research and the Microsoft Digital Crimes Unit. 2012. The role of technology in human trafficking—RFP winning proposals announced. http://research.microsoft.com/en-us/collaboration/focus/education/human-trafficking-rfp.aspx (accessed April 10, 2013).

Miller, A., and D. Rubin. 2009. The contribution of children’s advocacy centers to felony prosecutions of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse and Neglect 33(1):12-18.

Multnomah County. 2012. Multnomah County: Community response to Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children (CSEC). Multnomah County, OR: Department of Community Justice.

Nair, P. M. 2011. Theme-1: Multidisciplinary and multistakeholder approach in the capacity building and empowerment of responders on human trafficking. http://www.wjp-forum.org/2011/blog/multidisciplinary-and-multistakeholder-approach-anti-human-trafficking-1 (accessed August 20, 2012).

Nasser, M. 2012. Site visit presentation to the Committee on the Commercial Sexual Exploitation and Sex Trafficking of Minors in the United States, on the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Northern District of Illinois, July 11, 2012, Chicago, IL.

National Children’s Alliance. 2013. History of National Children’s Alliance. http://www.nationalchildrensalliance.org/index.php?s=35 (accessed on January 4, 2013).

National Sexual Violence Resource Center. 2006. Report on the national needs assessment of sexual assault response teams. Enola, PA: National Sexual Violence Resource Center.

Newton, P. J., T. M. Mulcahy, and S. E. Martin. 2008. Finding victims of human trafficking. Chicago, IL: National Opinion Research Center.

Nicholson, D., S. Artz, A. Armitage, and J. Fagan. 2000. Working relationships and outcomes in multidisciplinary collaborative practice settings. Child and Youth Care Forum 29(1):39-73.

Nowell, B., and P. Froster-Fishman. 2011. Examining multi-sector community collaborative as vehicles for building organizational capacity. American Journal Community Psychology 48:193-207.

Office of Justice Programs. 2011. OJP fact sheet: Human trafficking. http://www.ojp.usdoj.gov/newsroom/factsheets/ojpfs_humantrafficking.html (accessed February 4, 2013).

Office of Justice Programs. 2013. What is a SART? http://ovc.ncjrs.gov/sartkit/about/aboutsart.html (accessed April 27, 2013).

OJJDP (Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention). 1998. Forming a multidisciplinary team to investigate child abuse. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, OJJDP.

OVC. 2013. OVC-funded grantee programs to help victims of trafficking. http://www.ojp.gov/ovc/grants/traffickingmatrix.html (accessed April 10, 2013).

OVC and BJA. 2011. Anti-human trafficking task force strategy and operations e-guide. Washington, DC: OVC and BJA. https://www.ovcttac.gov/TaskForceGuide/EGuide/Default.aspx (accessed July 5, 2013).

OVC and BJA. 2013. Enhanced collaborative model to combat human trafficking FY 2013 competitive grant announcement. https://www.bja.gov/Funding/13HumanTraffickingSol.pdf (accessed April 27, 2013).