1

Historical Context Regarding Planning for Future Air Force Capabilities

The men in charge of the future Air Forces should always remember that problems never have final or universal solutions, and only a constant inquisitive attitude toward science and a ceaseless and swift adaptation to new developments can maintain the security of this nation through world air supremacy.

—Theodore von Kármán, 19451

In the spring of 1911, the young Lieutenant Henry H. “Hap” Arnold was sent to Dayton, Ohio, to learn about aviation from the Wright brothers, on what is now the site of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.2 From that date on, the development and application of technology has been an essential part of U.S. airpower, leading to a century of air supremacy. But that developmental path has rarely been straight, and it has never been smooth. Only the extraordinary efforts of exceptional leadership—in the Air Forces and the wider Department of Defense (DoD) in science and in industry—have made the triumphs of military airpower possible.

The earliest years of the U.S. Army Air Service were marked by mere halting steps in technological development, as the United States fell far behind the powers

_________________

1 Dik A. Daso, Architects of American Air Supremacy: Gen. Hap Arnold and Dr. Theodore von Kármán, Air University Press, Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala., 1997, p. 322.

2 H.H. Arnold, Global Mission, Harper, New York, 1949, pp. 15-29.

of Europe. Of all the factors that led to the defeat of Germany in World War I, U.S. aviation technology was clearly not one of them.

By the time the Armistice came, we did have 2,768 completely trained pilots and observers on the Western Front. Out of 20,000 officers and 149,000 enlisted men of the Army Air Service at home and abroad, almost 40 percent of the officers and 50 percent of the enlisted men were in France or at advanced training bases in England. Many more would have been there if there were airplanes for them…. No American-designed combat planes flew in France or Italy during the entire war.3

General Arnold was the first—and thankfully not the last—in a tradition of visionary airpower leaders who understood that U.S. air forces would always need to rely on technological advances rather than superiority in numbers. He also understood that those technology breakthroughs were not likely to come solely from within the Air Corps, but also from partners in academia, science, engineering, and business. He made his views on the matter clear in a 1937 speech, shortly before he became the U.S. Army Air Corps Chief.

Remember that the seed comes first: if you are to reap a harvest of aeronautical development, you must plant the seed called experimental research. Install aeronautical branches in your universities; encourage your young men to take up aeronautical engineering…. Spend all the funds you can possibly make available on experimentation and research. Next, do not visualize aviation merely as a collection of airplanes. It is broad and far-reaching. It combines manufacture, schools, transportation, airdrome building and management, air munitions and armaments, metallurgy, mills and mines, finance and banking, and finally, public security—national defense.4

To General Arnold, this emphasis on partnership was an essential part of planning for future airpower capabilities. He reached out to an unprecedented consortium of strategic thinkers at leading universities, as well as to inventors, aviators, aeronautical designers, automotive manufacturers, and financiers. He always recognized the need for these partnerships, because he believed that the degree of specialized genius required to plan for future Air Force capabilities was unlikely to be found solely within the ranks of the Air Force. Under the auspices of the National Academy of Sciences, he held meetings of top experts, meetings at which the military and scientific cultures did not always mix well.

Few high ranking Army officers seemed aware of the close relationship developing between these specialists and the little Air Corps—a relationship that was to grow to such importance in World War II that civilian scientists would work side-by-side with staff officers in our overseas operational commands, frequently flying on combat missions to increase their data. Once, after George Marshall became Chief of Staff, I asked him to come to lunch with

_________________

3 Ibid., pp. 61-64.

4 Daso, Architects of American Air Supremacy, 1997, p. 57.

a group of these men. He was amazed that I knew them. “What on earth are you doing with people like that!” he exclaimed. “Using them,” I replied. “Using their brains to help us develop gadgets and devices for our airplanes—gadgets and devices that are far too difficult for the Air Force engineers to develop themselves.”5

THE RISE OF DEVELOPMENT PLANNING

In the years following World War II, planning for future Air Force capabilities waxed and waned. General Curtis E. LeMay was a brilliant combat leader, but perhaps not the best choice to lead Air Force research and development (R&D) activities in 1946. His thinking tended to be short term—“Lemay’s responsibilities were largely tied to here-and-now requirements.”6 His short stint leading all Air Force R&D—he was off to command U.S. Air Forces in Europe within a year—was not exactly a highlight of his career.

I certainly hadn’t been screeching with enthusiasm about my new duties, but it didn’t take me long to become mighty interested. It was strictly a management job. I didn’t know much about Research and Development…. I still could never forget that I essentially considered myself a field commander.7

At the other end of the spectrum were leaders who exemplified General Arnold’s ideas about fresh thinking, close partnerships, and long-term vision. No better example exists than the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), led by General Bernard Schriever. Through the 1950s, while operational field commanders like General LeMay focused on improving current systems like the B-52, visionaries like General Schriever used alliances among scientists, technologists, manufacturers, and acquisition leaders to create a series of powerful missile systems—Navajo, Bomarc, Thor, Atlas, Titan, Minuteman—at an almost unimaginable pace. (For a long time, General LeMay, by then Commander in Chief of the Strategic Air Command, was notably unimpressed, referring to ICBMs and their thermonuclear warheads as Schriever’s “firecrackers.”8)

Many of the challenges arising in today’s acquisition environment are reminiscent of those that have come before. But organizational memory can be fleeting, and lessons learned today may be forgotten tomorrow. Changing threats, shifting requirements, ineffectual processes, chronic funding issues, and excessive oversight

_________________

5 Arnold, Global Mission, 1949, p. 165.

6 Daso, Architects of American Air Supremacy, 1997, p. 160.

7 Curtis E. LeMay and MacKinlay Kantor, Mission With LeMay; My Story, Doubleday, Garden City, N.Y., 1965, p. 400.

8 To see how the perspective of visionaries and operators can clash, see Neil Sheehan, A Fiery Peace in a Cold War: Bernard Schriever and the Ultimate Weapon, Random House, New York, 2009.

have existed as long as there has been a U.S. Air Force—and even before. In his 1949 autobiography, General Arnold explained as follows:

The tough part of aircraft development and securing an air program is to make Congress, the War Department, and the public realize that it is impossible to get a program that means anything unless it covers a period of not less than five years. Any program covering a shorter period is of little value. Normally it takes five years from the time the designer has an idea until the plane is delivered to the combatants. The funds must cover the entire period or there is no continuity of development or procurement. For years, the Army—and the Army Air Forces while a part of it—was hamstrung in its procurement programs by governmental shortsightedness.9

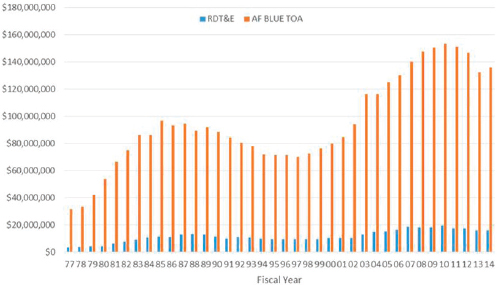

Around the time that General Arnold was writing these words, the newly established Air Force was creating the Ridenour Committee to study the Air Force’s R&D activities.10 The Ridenour Committee recommended the creation of a new organization, separate from the Air Materiel Command, to control all of the Air Force’s R&D. By the mid-1950s, there was recognition that formal channels were needed to connect combat commands, the science and technology (S&T) community, and acquisition program offices. These ideas resulted in the establishment in 1960 of an organization called the Advanced System Program Office, which was tasked with developing mission requirement analysis and operational assessment tools and using them to focus technology development.11 Figure 1-1 shows Air Force research, development, test, and evaluation (RDT&E) funding as a part of Air Force total obligation authority over time.

VANGUARD, APPLIED TECHNOLOGY COUNCILS, AND THE AIR FORCE SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY BOARD

The first development planning offices were begun in the 1960s, and their processes and policies were defined over the following years. In 1978, the Commander of Air Force Systems Command (AFSC), General Alton D. Slay, saw the need for a more comprehensive and complex development planning methodology.

In General Slay’s view, the development planning activities that did occur were conducted primarily by Pentagon or AFSC elements, with insufficient involvement

_________________

9 Arnold, Global Mission, 1949, p. 156.

10 Kent C. Redmond and Thomas M. Smith, From Whirlwind to MITRE: The R&D Story of the SAGE Air Defense Computer, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2000, p. 23.

11 John M. Griffin and James J. Mattice, “Development Planning and Capability Planning, 1947 to 1999 and Beyond,” unpublished manuscript, 2010, pp. 5-6.

FIGURE 1-1 Air Force research, development, test, and evaluation funding as a part of Air Force total obligation authority over time (in $1,000s and “then-year dollars” versus constant or inflation-adjusted dollars). NOTE: Air Force RDT&E spending (in blue) tends to track with the overall Air Force budget, but with less variation. The funding chart reflects the geopolitical realities of the past 40 years: The post-Vietnam Carter years; The Reagan buildup of the 1980s; the “peace dividend” of the 1990s, and the military commitments in the Middle East and southwest Asia since 9/11.

from the field—the warfighters. As a result, General Slay began a new program to revitalize development planning by making it cohesive, cross-cutting, inclusive, and efficient. This new development planning effort was known as “Vanguard.”

With Vanguard, General Slay split the management of technology into two pieces. The first, what he called “planning for development,” was acquisition based; it codified user requirements and determined the systems, costs, schedules, and plans necessary to meet those requirements. The second piece was called “development planning,” and it was technology based, coordinating all research and development in the Air Force, focusing on Exploratory Development (budget category 6.2) and Advanced Development (budget category 6.3). Vanguard used advanced computer tools to increase visibility into technology efforts across all fronts, throughout industry, and across the armed services. A channel was established within the AFSC, from the Deputy Chief of Staff for Development Plans down to each individual program office and laboratory, through which Vanguard data were accumulated, sorted, analyzed, and redistributed. Participation was not optional.

Vanguard’s success hinged on a tool known as “hooks and strings,” which provided the linkages between the combat commands, the S&T world, and the acquisition centers. In connecting the three worlds, hooks and strings answered critical questions that are as important today as they were 35 years ago (see Box 1-1). Vanguard included the following three core planning areas: (1) mission plans, (2) major force elements, and (3) functional plans. Mission-level plans addressed specific tasks that must be completed, whereas major force elements included larger and more general categories of systems that would garner interest across the board. Functional plans

BOX 1-1

The Objectives of Vanguard

The Vanguard “hooks and strings” tool provided answers to the following questions:

• Do all Air Force advanced development (budget category 6.3) projects have a clear and recognized trace back to some stated Air Force capability, deficiency, or operational requirement?

• Do all advanced development (budget category 6.3) projects have a clear and recognized trace forward to some on-going, planned or projected engineering, or manufacturing development program or project?

• Do all advanced development (budget category 6.3) project funding profiles and schedules take into account the schedules of engineering and manufacturing development (EMD) programs or projects which they support?

• Do all Air Force exploratory development (budget category 6.2) projects have a clear trace to some existing or projected and officially recognized technology shortfall?

• Do all Air Force exploratory development (budget category 6.2) projects have a clear and officially recognized “path” to advanced development or to some other exploitation of the generated technology?

• Do all defense industry independent research and development (IR&D) projects supported directly by Air Force funds have a clear trace directly to some existing and officially recognized technology shortfall which, if filled, would enhance the ability of the Air Force to perform its mission?

• Can assurance be provided that technology work accomplished or under way by the Air Force laboratories is not duplicated in contracts issued to defense contractors by Air Force program offices?

• Can assurance be provided that each Air Force EMD program office fully recognizes and exploits the technology accomplishments and advances made by the Air Force laboratories which are applicable to the EMD program or project?

• Can each Air Force EMD program office be provided access to “entry level” information from all sources (Air Force laboratories, other Air Force programs or projects, other Services, defense industry) which identifies all available technology specifically related to their program or project?

____________

SOURCE: Derived from an undated talking paper by General Alton D. Slay (USAF, Ret.) entitled “Vanguard.”

addressed those activities that spanned several mission areas. All these plans were supported by a wealth of information, such as applicable citations from the Air Force’s out-year development plan, relevant regulations, pertinent organizational dependencies, and proposed schedules, milestones, and requirements.

Key parts of Vanguard were frequent, regular, face-to-face meetings at the four-star level, to facilitate coordination among all parties. In the words of General Slay,

I hosted separate meetings each quarter at HQ AFSC with the operational commanders (e.g., SAC, MAC, TAC) and selected members of their staffs. Vanguard briefings described the Vanguard “hooks and strings” trace to all projects/ programs underway or planned in response to their requirements. Project funding levels and schedules were discussed in detail and comments solicited thereon.12

The results of Vanguard were mixed, according to its creator. Asked about his own level of satisfaction with the Vanguard implementation as of his retirement in 1981, General Slay said,

On the whole, I would rate my degree of satisfaction with its implementation as something just north of lukewarm. Maybe if I had been able to stick with it another year….13

This loss of momentum described by General Slay is an important feature of this story. From General Arnold to General Slay to today’s Air Force leadership, a common thread emerges again and again: A strong leader sees the need for a better system to integrate the warfighter, S&T, and acquisition worlds and creates a new management system to fill that need. With the powerful support of the senior leadership, the new management system is developed and implemented. But it is not long before the new system itself comes under fire. Perhaps the sponsoring leader moves on, or priorities change, or the system comes under attack from the outside.

Such was the case with Vanguard. The details of its demise are neither well documented nor well remembered, but it certainly faded away after General Slay’s 1981 retirement and subsequent criticism by watchdog agencies within government.14

_________________

12 Arnold, Global Mission, 1949, p. 4. Note: SAC, Strategic Air Command; MAC, Mobility Air Command; TAC, Tactical Air Command.

13 Ibid., p. 6.

14 For a deeper look at Vanguard, its successes and its shortfalls, a good source is an Air Force Institute of Technology master’s degree thesis, “An Evaluation of the Top-Level Air Force Long Range Planning Model Based on a Set of Planning Factors To Determine the Feasibility for Implementation,” by Captain Fredric J. Weishoff, September 1990, Air Force Institute of Technology, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio.

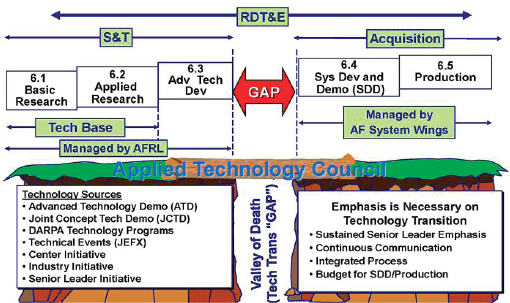

After the end of Vanguard, when it became clear that the need for coordination between the worlds of warfighters, S&T, and acquisition commands still existed, a new concept evolved at the product center level. Applied Technology Councils (ATCs) were instituted by product center and laboratory commanders to carry on the old Vanguard mission of integrating warfighter requirements with acquisition priorities and laboratory efforts (see Figure 1-2).

The major mission of the ATCs was to address the issue of the “valley of death,” a term used to describe the gap between funds allocated to develop a technology and the funds needed to support acquisition and testing to transform the technology into an operational capability. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Air Force had evolved to the point where final funding support in the budget came primarily from the using commands, the warfighters. If the warfighters did not understand a specific technology or how it related to their own operational needs, they tended to not support funds to carry the system through the valley of death. The ATCs were an attempt to ensure that warfighters clearly understood what was being developed

FIGURE 1-2 Applied Technology Councils (ATCs) serve to bridge the “valley of death” technology transition gap between budget category 6.3 and 6.4. SOURCE: Colonel Arthur Huber, Vice Commander, Aeronautical Systems Center, and Gerald Freisthler, Executive Director, Aeronautical Systems Center, presentation to the Committee on Evaluation of Air Force Pre-Acquisition Technology Development, June 1, 2010.

in laboratories and product centers and, consequently, better understood their role in funding that critical bridge across the valley of death.

ATCs were thus instituted by product center and laboratory commanders to carry on the old Vanguard mission of integrating warfighter requirements with acquisition priorities and laboratory efforts. As with the Vanguard meetings, ATCs were scheduled quarterly and attended by senior-level warfighters, top laboratory management, and high-level acquisition leaders. Warfighters clarified their combat requirements, S&T leaders explained what was feasible technologically, and the acquisition community laid out programmatic plans for matching requirements with new systems or subsystems. Priorities were established, funding was committed, and plans were made to transition technologies from the S&T world, over the valley of death, to operational success—all as in the days of General Slay’s Vanguard.

As with Vanguard, however, the ATCs were eventually allowed to erode past the point of usefulness, in at least some instances. The causes were many: Different commands had different assessments of the value of the ATC process. New commanders—whether warfighters, laboratory leaders, or top acquisition management—at times had other priorities. Sometimes, overtaxed leadership let the intervals between ATCs increase—from quarterly to semiannual, then to annual, and sometimes beyond that. The staffs of participating organizations began to require multiple pre-briefings, adding bureaucracy to the process and arguably watering down the frank dialog on what systems engineering is needed and why. Eventually, the rank—and the perspective and the power—of ATC attendees declined: What had at one time been meetings of lieutenant generals eventually became meetings of lieutenant colonels who generally lacked the required strategic view.

Vanguard and ATCs were both aimed at integrating the needs and capabilities of operational commands, S&T organizations, and acquisition centers. Both enjoyed some success, and both eventually declined in importance. As with the demise of Vanguard, the erosion of ATCs in some areas represents a significant setback in the pursuit of a fully integrated technology development and systems acquisition mission.

The Role of the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board

The U.S. Army Air Force’s Scientific Advisory Group (SAG) (later known as the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board, AFSAB) was formally commissioned by General Arnold in 1944 to advise him and to guide the technological strategies of the Army Air Forces. Led by General Arnold’s trusted colleague and advisor Theodore von Kármán, the SAG provided the foundation and blueprint for General Arnold’s vision of Air Force technological supremacy. Its prescient 1945 report,

Toward New Horizons, foresaw many of the scientific developments that would come to fruition over the next seven decades, which are taken for granted today.15, 16

The AFSAB, like so many other activities related to development planning, has gone through good times and bad in the past 70 years, but it continues today.17 While not directly involved in the development planning process, the AFSAB has played an important role in the management of technology and innovation through its summer studies and its annual assessment of S&T activities in the laboratories. In those reviews, the AFSAB assessed laboratory programs for both technology excellence—that is, how laboratory activities rate in relationship to “best-of-class” R&D and how they rank in accordance with relevance to warfighter needs. It was understood among the Air Force research laboratories, the AFSAB, and warfighters that the warfighter would be unlikely to support further funding for a technology research effort that was either technically deficient or failed to meet standards of relevance that spanned from near-term requirements to longer-term envisioned needs that would enable operational dominance and avoid technology surprise. Thus, the AFSAB had an influence on what technologies ultimately were developed.

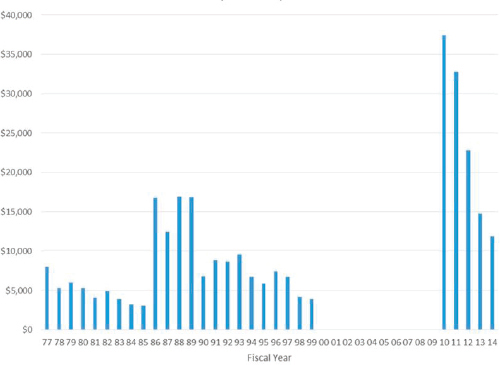

Vanguard and development planning cost money, of course, and that money had to come from somewhere. In 1986, the General Accounting Office (GAO; now the Government Accountability Office), released a review of AFSC’s Aeronautical Systems Division’s assessment of authorized programs to fund and account for certain development planning activities titled Appropriated Funds: Air Force Needs to Change Process for Funding Some Activities (see Figure 1-3).18 Beginning in fiscal year (FY) 1981, Congress slashed funding for the Air Force’s development planning work.19 But, despite the reduction of congressionally appropriated funds, AFSC’s spending on development planning climbed from less than $1 million in 1982 to more than $20 million in 1984.20 To support development planning efforts, includ-

_________________

15 U.S. Army Air Force Scientific Advisory Group, Toward New Horizons, multi-volume report to General of the Army H.H. Arnold, 1945.

16 The scanning of scientific innovation was part of the role of the SAG/SAB. Toward New Horizons was a textbook example, addressing all sorts of scientific breakthroughs that could be capitalized upon by the Air Force. Some of the topics in Toward New Horizons presage such modern developments as unmanned aerial vehicles, automatic target recognition, and precision “fire and forget” weaponry, among other things.

17 General LeMay in particular had some skepticism about it; see Daso, Architects of American Air Supremacy, 1997, pp. 160-162.

18 GAO, Appropriated Funds: Air Force Needs to Change Process For Funding Some Activities, GAO 86-24, Washington, D.C., January 1986.

19 Ibid.

20 Ibid., p. 8.

FIGURE 1-3 Air Force spending for development planning from fiscal year (FY) 1977 to FY 2014 (in $1,000s and “then-year dollars” versus constant or inflation-adjusted dollars). NOTE: Stability of funding for development planning has been inconsistent at best, and was actually zeroed from FY 2000 through 2009. In periods where funding plummeted, Air Force leaders were forced to adapt and innovate, in attempts to keep development planning alive. The committee’s research revealed that there were at times major differences between development planning funding, and actual spending on development planning. SOURCE: Jerry Lautenschlager, Development Planning Program Element Monitor, Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Science, Technology, and Engineering.

ing Vanguard, the Air Force began to “tax” existing programs of record to support development planning, even for unrelated systems. For one example, beginning in 1982, just after General Slay’s retirement, existing aircraft programs, including the B-52 and B-1, were assessed $1.7 million to support development of space vehicles.

Not surprisingly, the GAO took some exception to this. In its response to the criticisms in the GAO’s 1986 report, DoD agreed that the Air Force’s accounting was indeed a bit too creative, and DoD agreed to direct the Air Force to cease its practice of taxes and assessments to support development planning. But this would not be the last time that development planning would face a loss of funding, nor would it be the last time that Air Force leaders would try to find ways to keep it alive.

Whenever appropriated funding for development planning withered, leaders throughout AFSC (and its successor, the newly formed Air Force Materiel Command) were forced to adapt to the new and dangerous financial reality. Continuing to recognize that the need to plan for the future is essential, the acquisition and development communities tried various ways to substitute for the lack of institutional funding. As seen previously, centralized “taxation” of programs was prohibited as a result of the 1986 GAO report. However, some product center commanders urged program directors under their command to carve out a portion of their appropriated funds to look at future capability modifications that could enhance their individual programs in the future. For example, the F-16 System Program Office had the authority and funding to look into the future for technologies and architectures to keep the F-16 platform relevant into the 21st century. That project, begun in 1982 and called “Falcon Century,” was a mini-development planning process, focused on that one platform.21

THE DECLINE OF DEVELOPMENT PLANNING

Contributing to the decline in development planning within the Air Force was what some have described as the “perfect storm” of circumstances. During the early 1990s, the Air Force began a series of actions to both downsize and reorganize after the collapse of the Soviet Union and to right-size the Service for the future. These actions were a recognition that resources for the military would probably decline in the new post-Soviet Union era. The Air Force leadership decided to combine major commands with common or complementary missions as the primary focus of its reorganizations. Therefore, the former Strategic Air Command (SAC), with its strategic bomber force, was combined with Tactical Air Command (TAC), with its fighter aircraft forces, to create Air Combat Command (ACC). Similarly, AFSC, whose mission was the research, development, and acquisition of new weapon systems, was combined with Air Force Logistics Command (AFLC), whose mission was the maintenance and sustainment of weapon systems, to create Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC).

One of the primary objectives for creating AFMC was to eliminate the perceived problem of developing weapon systems in one command (AFSC) without adequately considering the long-term implications and costs of how to sustain that same weapon system for years, or even generations, in the future in another command (AFLC). AFMC was envisioned to provide the Air Force with a single command that looked at weapons development from cradle-to-grave and planned

_________________

21 Frank Camm, The F-16 Multinational Staged Improvement Program: A Case Study of Risk Assessment and Risk Management, Rand Report N-3619-AF, 1993, available at http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a281706.pdf.

their designs and capabilities up front with maintenance as a forethought, not an afterthought.

Development planning was a major process in AFSC. As part of the perfect storm mentioned earlier, the funding for development planning was also being reduced significantly around the same time as the Air Force began its reorganization to create ACC and AFMC. The operational pull and requirements strengths of SAC and TAC, which informed the front-end of the development planning process, suffered as the new ACC was being formed. Simultaneously, the objectives and mission of AFMC led to a renewed emphasis on the transition between the development of a new system and its maintenance/sustainment. Initially, AFMC even created an Integrated Weapon Systems Management (IWSM) process as the hallmark of the new command. IWSM’s key focus was on the smooth transition between development and sustainment, not the front-end development of a system that was the primary focus of development planning. As AFMC was being established and IWSM was maturing, the commander of AFMC stated that the decision to locate the new command at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base was made to counter the perception that sustainment, maintenance, and logistics were being de-emphasized in the Air Force at the expense of R&D. AFMC’s commander also stated that he would probably have to spend most of his time working sustainment issues for the corporate Air Force because of their long-term implications and costs, instead of S&T or R&D and acquisition issues.

Finally, the location of AFMC at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base had the secondary effect of removing a “four-star” champion for development planning from the crucial, time-critical decision-making apparatus of the Pentagon and Congress. All of these factors helped define a perfect storm of circumstances that contributed to the decline of development planning within the Air Force.

In reviewing the history of what has become known as development planning, one thing stands out, not for its historical presence, but for its absence: In none of the Air Force histories reviewed by the committee did leaders perform, or cite, what today would be called a formal cost-benefit analysis. General Arnold never once wrote of modern corporate concepts like return on investment or internal rates of return. Surely, this is at least partly due to the impossibility of reducing issues of war and peace, and the relevance therein of revolutionary technologies, to mere financial or quantitative terms. But it also reflects another reality: For the people who built the Air Force, keeping that Air Force at the cutting edge technologically was instinctive. They did not need to hear fiscal arguments about payback on current investment and future rates of return. They knew and accepted a much more important relationship—that technological progress leads to victory in war.

This is important to understand: In the research for this report, the committee heard more than once that the funding turbulence and fiscal shortfalls plaguing development planning were a result of no one making the case for development planning to senior leadership. As intuitively appealing as that argument seems, it is also disingenuous. No subordinate made the argument for technology to those Air Force pioneers, because it was unnecessary. They already understood the importance, and they knew that an effective process for supporting technological development was their responsibility, as the top leadership. From a 1945 letter from General Arnold to his successor, General Spaatz,

In connection with programs for scientific research … it is of the utmost importance that there be no administrative obstructions between the officer in charge of these research problems and programs and the Commanding General of the Army Air Forces. As I visualize it, in time of peace the one man who should have time to think more than anyone else in the whole Air Forces organization … is the Commanding General, Army Air Forces. He should be able to project himself farther into the future than any of the staff.22

Planning for future Air Force capabilities has followed an inconsistent path for much of the past century. Whether in the hands of legendary giants of aviation—Arnold, von Kármán, LeMay, Schriever, and Slay—or leaders less well known but no less knowledgeable, capitalizing on technological innovation has always been a priority for the Air Force. But countervailing pressures have also always existed—the immediate demands of wartime operations, financial constraints driven by domestic economic conditions, or changing political powers and priorities are just some examples. The results of all this—a variety of attempts by subordinate commanders to keep development planning alive and a fragmented development planning system that is well intentioned but lacking in clarity, consistency, and coherence—will be described in Chapter 2.

_________________

22 Letter from General Arnold to his successor, General Spaatz, 1945.