4

BioWatch Collaborative Planning

The objectives of the workshop’s fourth session were to explore the following:

- Review the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS’s) current collaboration activities across all levels of government and explore opportunities for additional collaboration and coordination between BioWatch and relevant federal, state, and local public health partners to support effective and efficient capability development.

- Discuss opportunities to strengthen the biodefense layer by identifying capabilities and partnerships that could be developed to respond in the event of a biological terrorism incident.

- Review ways that BioWatch activities can contribute to requirements placed on state and local public health departments for preparedness planning.

The session began with an overview presentation by Emily Gabriel, public health and preparedness director, BioWatch program, DHS. A panel of local public health officials, consisting of Mark Buttner; Kathy Forzley, health officer at the Oakland County (Michigan) Health Division; Julia Gunn; Philip Newton, policy advisor for biological preparedness, Homeland Defense Integration and Defense Support of Civil Authorities, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, Department of Defense (DoD); Roger Pollok; Al Romanosky; Wendy Smith; Sandy Wedgeworth, coordinator for public health emergency management at the City of Long

Beach (California) Department of Health and Human Services; and Jody Wireman, director of the Force Health Protection Division at U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM), then discussed the state of current local, state, and federal collaborations, after which the discussion was opened to workshop participants.

OVERVIEW OF BIOWATCH COLLABORATIVE PLANNING

The state and local operators of this program, said Emily Gabriel, are the BioWatch program’s customers. Her office has the responsibility to make sure that the local operators are getting what they need and that the BioWatch program is responding to their requests. One of the ways in which her office meets the needs of its customers, and of which the BioWatch program is most proud, is to collaborate with them and a number of federal partners in preparing to respond to a bioterrorism attack in general. This preparation, she said, is a tool that is not limited to bioterrorism.

The BioWatch program is engaged in multiple levels of collaboration, explained Gabriel. At the federal level, there is the federal BioWatch working group, which includes the program’s formal partners such as the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), DoD, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and Secret Service. The working group provides critical input to the BioWatch program and is a crucial component of the program’s efforts to protect the nation from bioterrorism. At the state and local levels, collaborative partners include public health officials, epidemiologists, veterinarians, law enforcement and intelligence, laboratory staff, and other officials who are members of the local BioWatch advisory committees. She noted that the BioWatch advisory committees have become important forums that bring people together in a way that may not have occurred otherwise to discuss matters including, but not exclusive to, the BioWatch program. She also said she and her colleagues work hard to foster the relationships between local programs and regional federal offices of agencies such as FEMA and ASPR.

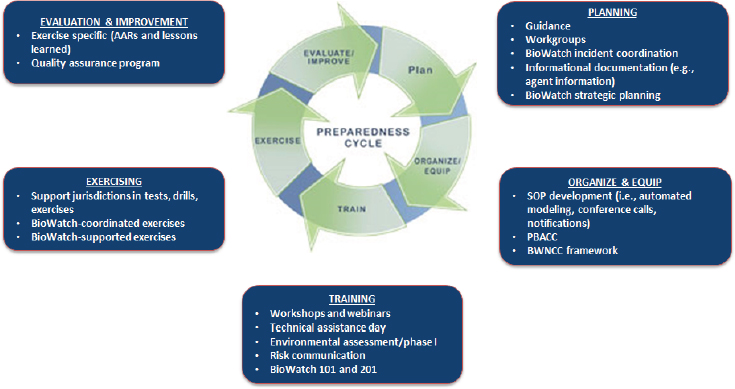

The crux of what BioWatch’s public health and preparedness section does is summarized by what Gabriel called the preparedness cycle (see Figure 4-1). She said that exercises and guidance are important and probably the best known components of the program, but there are more aspects to preparedness that her office supports. Each jurisdiction, she explained, develops its own response plan, and BioWatch does not dictate how a jurisdiction should respond to a BioWatch Actionable Result (BAR). In

NOTE: AAR = after-action review; BWNCC = BioWatch national conference call; PBACC = post-BioWatch Actionable Result (BAR) awareness conference call; SOP = standard operating procedure.

SOURCE: Gabriel presentation, July 28, 2016.

addition, the national program office also develops response plans, including an incident coordination document and process.

The guidance that BioWatch provides, said Gabriel, emphasizes the key pieces a local jurisdiction should incorporate into its response plan and the partners that should be engaged in the planning process. Guidance documents include an overview of the BioWatch program as well as a list of the program’s federal partners, their roles in supporting BioWatch, how they are connected, and how they can provide assistance and resources to state and local partners. There are also specific guidance documents for outdoor programs, indoor programs, special events, and environmental assessment. The guidance document for indoor deployment of the BioWatch system was developed with input from the few jurisdictions that have indoor deployments. This document, said Gabriel, outlines some of the important factors a jurisdiction needs to consider before even making a request for indoor deployment. Recently, the indoor and outdoor guidance documents were merged and will be going out for review in the next few months.

Gabriel explained that BioWatch had formed several workgroups to share lessons learned and best practices and to exchange ideas on how to improve the program. For example, one working group, the Public Health Engagement Network, was created to bring together public health stakeholders and others interested in public health to talk on a quarterly basis.

Recently, she noted, a veterinary-specific working group was rolled into the public health workgroup. BioWatch offers interactive webinars for this group on specific topics during which participants can ask and answer questions and exchange ideas that may benefit those in other jurisdictions. She recounted how at one quarterly conference call, a colleague from a jurisdiction that had been seeing a great deal of Francisella tularensis activity spoke to the program about how it has handled its response to this biological activity. “It is exciting when you see that dialogue and excitement and interest from one jurisdiction to another, and knowing that something one jurisdiction has experienced can benefit another,” said Gabriel.

Another working group, the public information officers’ network, is the most active group, said Gabriel, and it includes public information officers from around the country and from all of BioWatch’s federal partners. Among other topics, this group has been focusing on how to talk about BioWatch’s day-to-day planning and operations when speaking with an elected official who has limited time and no knowledge of the program. At one quarterly conference call, local public information officers spoke about how they were preparing for the two national political conventions. After the Super Bowl, the public information officers in the Bay Area spoke about what occurred during that time, how they responded, and what their communication practices were. She noted that these conversations help her office understand what tools these communicators might need in the future that could help them do their jobs better.

The BioWatch portal and its BioWatch toolbox are where the program shares information such as guidance documents, standard operating procedures, and fact sheets on specific biological agents with local jurisdictions. The portal’s toolbox is also becoming a place where the jurisdictions are sharing information with one another, posting the response plans and other documents that might be of interest to other jurisdictions. “That is something we had not seen before,” said Gabriel. She noted that information available via the toolbox is developed in a collaborative process with the local partners, and that her office has been putting more of the program’s accumulated knowledge into written form for inclusion in the toolbox.

The national BioWatch conference call is also an opportunity for collaboration, said Gabriel. The conference call brings together all of the federal partners and local stakeholders that would be experiencing a BAR to talk about what was happening. Recognizing that jurisdictions are busy during a BAR, there is also a post-BAR awareness conference call, typically held the day after the event, to rehash what happened and how the jurisdiction responded. She noted that while collaboration during planning is important, so, too, is collaboration during a response to a BAR, and she applauded how willing local jurisdictions have been to share information during a BAR. Gabriel added that if there is an urgent situation of which

the entire BioWatch community needs to be aware, a national conference call can be arranged within 4 hours.

Over the past few years, the BioWatch program has been building up its capacity to hold training exercises. Although it has been some time since the last national workshop was held—a new one is being planned—monthly, program-wide webinars, as well as workgroup-specific webinars, have been used as replacements for the national workshop. BioWatch program staff also spend time in person with local BioWatch advisory committees, and the program now offers technical assistance days. Gabriel explained that the toolbox provides a menu of offerings for topics that national program staff will come and address in depth. Risk communication has been the most requested subject, and Gabriel said one of the more successful training programs has been on environmental and Phase 1 sampling. She also said that when a local jurisdiction asks for advice on a topic that would be better addressed by another federal partner, she considers it her job to help connect the local jurisdiction with the right office in the right agency.

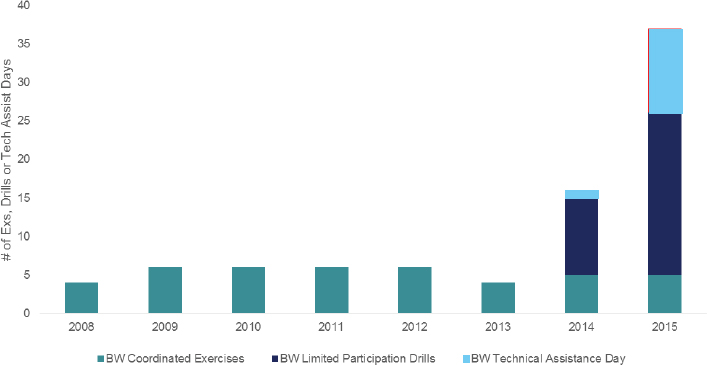

The program also offers an average of five complete BioWatch coordinated exercises per year, for which the BioWatch exercise team works with the local planning committee to design the training activity and then facilitates that exercise. However, that leaves the other 29 jurisdictions that cannot have a full training exercise each year. In response to stakeholder requests for more variety and flexibility in training, the program has tried to create opportunities for smaller drills that require fewer resources from the national program office, but allow for the local jurisdictions and BioWatch program office to interact within the resource constraints under which the national program operates. These limited drills can involve triggering a national conference call or a technical laboratory conference call, for example.

In addition, said Gabriel, some jurisdictions conduct training exercises on their own using federal emergency planning grants. Other jurisdictions are using BioWatch as a trigger for a Cities Readiness Initiative exercise, which includes enacting a full-scale dispensing of medical countermeasures. “We are very supportive of those exercise opportunities,” said Gabriel, who added that BioWatch collaborates with the jurisdictions to the extent that program resources make possible. In total, from 2008 to 2015, approximately 2,880 federal, state, and local stakeholders from a range of disciplines participated in BioWatch exercises. The addition of limited participation drills and technical assistance days allowed for a dramatic increase in the number of jurisdictions participating in BioWatch-related preparedness activities (see Figure 4-2).

Gabriel explained that the national program office prepares after-action reports after every training exercise in which it participates. With the permission of the local jurisdiction, these reports are made available to the rest

NOTE: BW = BioWatch; Ex = exercise.

SOURCE: Gabriel presentation, July 28, 2016.

of the BioWatch community. She noted that, historically, the local jurisdictions prepare their own after-action reports following a real-world BAR, but starting in 2015, when the program had its first BAR in 18 months, the national program office started preparing its own after-action report focusing on how it participated in the response and how it could improve its operations. For events such as the Super Bowl and National Special Security Events, including political conventions and the presidential inauguration, the BioWatch program office has guidance it prepared with CDC, EPA, and FBI and tries to foster collaboration among the host cities and the jurisdictions that have experienced those events. For the Super Bowl, the jurisdiction hosting the following year’s event will participate in the planning for the current event so it can learn what lies ahead and start preparing early.

DISCUSSION

Lisa Gordon-Hagerty opened the discussion by asking Gabriel to talk about any interactions BioWatch has with the agriculture and food supply communities, aside from its support for veterinarians. Gabriel replied that the Office of Health Affairs (OHA) has a branch that focuses on food, agriculture, and veterinarians, and the in-house veterinarians in that branch collaborate closely with colleagues at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Several years ago, she noted, the BioWatch national office

expanded the veterinary network. Mike Walter spoke to different associations and experts who are not fully involved with the BioWatch community to raise awareness of the program in the animal health community, and to explain the role of that community in looking for possible signs of a biological agent release that is affecting the animal population. In fact, she added, BioWatch has conducted a training exercise that focused exclusively on the veterinary response to a BAR and gained valuable lessons on how to better coordinate the flow of information between veterinarians and BioWatch.

As far as food safety issues are concerned, Walter said those are beyond the BioWatch program’s specifications. The program has been approached at various times to see if it could monitor for outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease or bovine spongiform encephalopathy. “From a technical perspective, we could, but the issue is one of responsibility and funding,” Walter explained. The USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) has primary responsibility in this area, and there have been conversations in the past about BioWatch setting up collectors near feedlots. Walter clarified that BioWatch’s involvement with the veterinary community is directed toward the companion animal population rather than the agribusiness sector, which is out of the program’s scope. That is not to say, Jonathan Greene added, that ensuring the safety of the nation’s food supply is not considered during the response to a BAR, and USDA, FEMA, DHS, and other agencies have discussed how to respond in the case of an animal outbreak. However, actually monitoring in the agribusiness sector is the responsibility of USDA and the Food and Drug Administration, and is not part of the BioWatch mission, Greene noted. He added that this area should be discussed with respect to the future of the program. Dave Fluty, principal deputy assistant secretary at OHA, DHS, added that U.S. Customs and Border Protection has an agreement with USDA to transfer 3,000 agricultural specialists who would become on-the-ground inspectors in the event of a threat of contamination of the international food supply. If the threat was significant enough, BioWatch detectors potentially could be deployed at ports of entry in the United States.

Al Romanosky suggested that if BioWatch became involved with the agriculture sector, he believes the most vulnerable point of attack and the place to deploy sensors would be produce fields at the time of any spraying operation rather than processing plants, where USDA already has inspectors. Jonathan Greene said doing so would require extending the capability of BioWatch to detect a new set of agents. Romanosky added that in his view, the reasons to bring in the veterinary community that treats companion animals are both to track how widespread an outbreak is and to warn the veterinarians of their possible exposure to a biological agent. Gabriel noted that BioWatch uses open-source information, as well as information

from the jurisdictions, to track animal cases of the BioWatch agent-related diseases and makes that information available to the jurisdictions.

Pursuing this line of questioning further, Gordon-Hagerty asked if BioWatch could detect something like wheat rust if intelligence pointed to a possible release. Walter replied that deploying sensors to detect a possible release in the wheat fields of Kansas is within BioWatch’s technical capabilities if provided with the necessary resources. One possible application that Romanosky suggested was to deploy sensors at feedlots to detect natural animal-to-animal spread of organisms such as Francisella tularensis. Walter thought that was an interesting idea if it could get funded and if BioWatch could adopt that mission with USDA’s approval. The federal BioWatch working group could be a venue for addressing this possibility with USDA.

James Lambert commended the program for considering the “why this program is important” as much as the “how it works” and for including that information into the guidance documents. One concern he has, based on a study he conducted in the Washington, DC, area on radiological emergency response, is that the public may not respond as expected to an announced bioweapon event. “We found there would be considerable unexpected behaviors, people would not do as they were told, they would not trust particular sources of information, and they would not have particular channels of communication available to them,” said Lambert. He encouraged BioWatch to gain an understanding of how third parties would react and if the BioWatch workforce would be able and willing to do what is needed in the event of a real-world release.

Gordon-Hagerty asked Gabriel if BioWatch has started to integrate improvement plans in its process based on information in the after-action reports from the exercises the program conducts. Such plans, she said, can be useful when seeking additional funds for program improvement, both at the federal level and for the localities. Gabriel replied that areas of improvement are part of what is identified and outlined in the after-action reports, though there are no separate improvement plan documents. She also noted that BioWatch jurisdictional coordinators check in with the local jurisdictions at 3, 6, and 12 months to see how they are progressing on responses to issues raised in the after-action reports. As far as whether the local jurisdictions develop a formal improvement plan, Gabriel guessed that they do not. Part of her responsibility, she said, is to make sure areas of improvement raised during the exercises are triaged internally and addressed, either by BioWatch, its federal partners, or the local jurisdictions, while recognizing and respecting the fact that BioWatch is not anyone’s full-time job outside of those working in the national program office and DHS. Gabriel added that she had not considered that the jurisdictions might find improvement plans useful for getting federal emergency planning grants or securing additional funding for their programs.

Daren Brabham commented that the exercises are likely to be a good source of best practices that could then be codified in guidance documents. Lambert, referring to Gabriel’s statement that jurisdictions are starting to post documents to the BioWatch portal, asked if the majority of those contributions are coming from a few jurisdictions. Gabriel answered yes, and that getting more participation is one of her biggest challenges, given that most people in the local jurisdictions wear multiple hats and have little spare time. She noted, though, that when she asks someone in a local jurisdiction to add a document to the portal, the answer is never no. She has also observed that once a jurisdiction sees the benefit of having information from another jurisdiction about how to handle a particular issue, the willingness to share increases. She said she welcomed any ideas on how to attack this problem. Lambert suggested having someone from her office reach out periodically to ask for contributions. Gabriel thanked him for that idea and said the jurisdictional coordinators, who are close to the local programs, could identify topics to showcase and be the ones to solicit those contributions.

Terry Mullins said he spoke to the director of Arizona’s state laboratory in preparation for this workshop, and the director, who is intimately involved with BioWatch, reported that the technical assistance and support he receives from the national program office has been extraordinary. He then asked if the national program office’s job is made more difficult by the fact that many jurisdictions may have multiple people in charge of various aspects of the program, and by turnover of personnel at the state and local levels. Gabriel replied that the local BioWatch advisory committee chair serves as the contact point for the national program office with support from the jurisdictional coordinator. She noted that the structure of the advisory committee varies across jurisdictions, but it is the advisory committee chair who determines how coordination and communication take place. Turnover, however, is one of the biggest challenges because education about the program, its mission, and how it is implemented is such an important component of BioWatch. She said she suspects that turnover is a big issue for the advisory committees as well.

Jack Herrmann, a senior program officer with the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, asked if there was a “BioWatch 101” video on YouTube that new local staff could watch to learn about the program. Gabriel replied that she had not thought of using YouTube, but that there is a webinar available that jurisdictions have found useful. Herrmann noted that CDC’s H1N1 influenza YouTube videos were shown to be helpful to those who viewed them and added that running a similar video on YouTube could also serve as a corrective tool for those in the media who want to portray BioWatch as “just a refrigerator that captures dust.” Gabriel said this was a good idea that she would raise with Walter

and that it could raise awareness of the program because only a limited public BioWatch website is available.

Romanosky pointed out that distributing after-action reports could be problematic because they raise shortcomings that could serve as fodder for program critics. What he would like to see happen is for BioWatch to conduct a de-identified data analysis of the accumulated reports to identify the most common failure points reported by multiple jurisdictions. Gabriel replied that the national program office does exactly that on an annual basis and posts the results of those analyses in the online toolbox as part of the exercise toolkit. These analyses look for both common problems and common successes, and she and her team are looking for additional ways to analyze those reports to make them even more useful to the jurisdictions.

CURRENT LOCAL, STATE, AND FEDERAL COLLABORATIONS

The panel session, moderated by Mullins, began when he said he was anxious to hear how federal resources are playing out in the day-to-day activities in the local jurisdictions. He then asked Jody Wireman to explain DoD’s operational role in mounting a response to a biological agent release in the United States. Wireman explained that DoD installations can provide support locally through their immediate response authorities and memorandums of agreement, and USNORTHCOM, the operational arm for any DoD response, coordinates additional DoD support where needed.

USNORTHCOM, said Wireman, supports the lead federal agencies that plan and respond to natural disasters such as hurricanes and earthquakes, as well as events such as chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) attacks. USNORTHCOM has approximately 5,200 individuals, half National Guard members and half DoD members, in its CBRN response enterprise. A DHS liaison at USNORTHCOM Headquarters advocates for USNORTHCOM involvement in various DHS programs when appropriate, including BioWatch. In fact, a memorandum of understanding enables USNORTHCOM to participate in BioWatch national conference calls, webinars, and other information-sharing activities and to access the BioWatch portal and toolbox.

Wireman said the BioWatch staff has always been upfront about what BioWatch can and cannot do technologically, and the program has been direct in letting USNORTHCOM know who is managing each jurisdiction’s BioWatch system and when they are performing exercises. He added that DoD benefits directly from these systems through a military installation’s proximity to the jurisdictional areas, and in some cases, military bases are in those jurisdictional areas. BioWatch also benefits USNORTHCOM’s ability to prepare for and respond to biological events. He likened BioWatch’s

early warning capabilities as akin to the North American Aerospace Defense Command serving as an early warning for ballistic missile defense.

Any improvements to the BioWatch program, said Wireman, could be made through continued coordination with federal agencies and by increasing the number of exercises conducted in conjunction with FEMA and HHS. The latter, he said, offers the possibility of helping the local jurisdictions as they develop response plans that cover all phases, from detection and verification to response and recovery. He also suggested involving the Defense Threat Reduction Agency in joint risk communication activities.

Philip Newton noted that DoD has long been an interested partner in BioWatch. “It is something we have found very valuable, both as a participant and as a customer of the information and results that come out of it,” said Newton. In the past, he noted, many DoD installations had sensors, but budget cuts have reduced the program’s footprint on military installations. In his opinion, more collaboration could occur at the installation level beyond those that already exist for mutual fire support and public health emergencies. Encouraging participation at the installation level, however, is hard when it comes from the Pentagon or USNORTHCOM, said Newton. He suggested that contacts between state and local BioWatch personnel and the local military installations could be a better way to encourage installations to become more involved partners. “Base commanders want to be part of their communities, so having interest come to us would be fantastic,” said Newton. “I cannot tell you how important that would be.”

Kathy Forzley, who has been involved with BioWatch for 8 years and is the current BioWatch advisory committee chair for the four jurisdictions in the Detroit metropolitan area, said the advisory committee chair rotates among the health officers of these four jurisdictions to ensure that everyone stays fully integrated in the program and that there is always experience among the committee members. She explained that BioWatch is “hardwired” into each of the four jurisdictions and is considered an important component of the region’s emergency preparedness programming. For example, the telephone call scripts created for BioWatch have been used as a template for all call scripts in the entire region for any kind of risk communication. “They look the same, they sound the same, and we work through a very methodical process in our call script, all of which came about because of BioWatch,” said Forzley. She also credited BioWatch with improving communication and preparedness planning among the jurisdictions and for having federal, state, and local representation all represented in that planning. In particular, she noted that the Michigan Department of Agriculture and the veterinary community have been active participants in planning for a biological attack and responding to a BAR.

Forzley said that involving public health with the BioWatch advisory committee has been an advantage in bringing partners to the table because

public health is recognized as a neutral convener in the Detroit area. “We are experienced at building strong collaborations and pride ourselves in doing that with the advisory committee as well,” she said, though noting that it has been challenging at times to show non-traditional partners such as the veterinary community and the Detroit zoo what their role can be in preparing for and responding to a biological attack. She suggested that holding a conference call with the OHA veterinary working group and the veterinarians in her area could help with that task.

Roger Pollok, who serves as the BioWatch advisory committee chair for the San Antonio area, said that BioWatch is one of the cornerstones of his jurisdiction’s planning and response enterprise for any type of regional public health emergency. Other cornerstones he listed included the CDC Strategic National Stockpile, the pandemic influenza stockpile, and the hurricane evacuation system. All of these pieces, he said, are networked together. Specific to BioWatch, there are more than 25 members on the advisory committee, including representatives of the local and state health departments, the laboratory, epidemiology, emergency preparedness, the Texas Center for Environmental Quality, and the Texas Division of Management, which oversees district-wide disasters. Federal agencies represented on the local advisory committee include DoD, FBI, and EPA, as well as the Red Cross. The biggest challenge he faces is turnover in committee membership. New individuals rotating into the program are required to go through the security clearance process and watch a 30-slide PowerPoint presentation to bring them up to speed.

Sandy Wedgeworth noted that the Long Beach health department is unusual in California in that it is one of only three city-run health departments, with the rest being part of county governments. Her program, therefore, coordinates activities across multiple counties. When she became involved with BioWatch 6 years ago, only two people in her department knew about the program, and nobody was allowed to talk about it. In fact, she was denied her request to work on BioWatch initially because of concerns stemming from the secrecy surrounding the program. However, 2 years ago, Long Beach public health realized it needed more partners involved in the program, and now she is the BioWatch advisory committee chair.

When she first approached the fire and police departments, they wanted to know why they had been kept in the dark for so long. “But once we got past that, they really did embrace the program,” said Wedgeworth. One of the deputy chiefs at the time asked why BioWatch was not deployed at the Long Beach Grand Prix, which was not something anyone in the local BioWatch program previously had considered. Collectors were deployed for the first time at that event in 2015, and it served as a test run that brought together public health and the hazardous materials response team for the

first time. “It was a great learning experience and we did get some support from DHS to do that,” said Wedgeworth.

Since then, BioWatch has gained a great deal of momentum in the region, and today there are more than 20 local, state, and federal agencies on the advisory committee. She, too, commented on the challenge of dealing with turnover; her solution has been to ask each agency to send two people to every advisory committee meeting. She noted that Long Beach has been using a federal emergency planning grant to support BioWatch in the absence of local funding, and that both the police and fire departments have absorbed the costs of their staff participation in trainings and other BioWatch activities. In fact, both departments will take an entire unit offline to participate in an 8-hour field exercise. Wedgeworth said she is looking for other funding sources because her program just lost 10 percent of its federal emergency planning grant funds, which has her worried about being able to cover the Grand Prix again. One surprising outcome of her quest for additional funds was that Long Beach’s congressional staff requested having one of its members on the advisory committee.

Addressing the GAO report, Wedgeworth said that as a local representative she believes it is part of her responsibility to counter some of the messages that have resulted from that report, which “really does not represent what we feel locally,” she said. “To me, the program is an absolute success if for no other reason than the fact that it has gotten all of us together in the same room and it has done such a great job of improving our ability to respond, not just to a biological attack, but anything that gets thrown our way.” She added that she could not have made that same statement even 1 year ago.

Al Romanosky started his remarks by praising the working relationship his jurisdiction has developed with the BioWatch national program staff. He noted that the BioWatch program he represents, which extends from Baltimore to Richmond and includes the District of Columbia, is perhaps unique in that it has to deal with the special challenges and visibility that come with being in the National Capital Region. Because of the involvement of so many counties, cities, and unincorporated areas in Maryland, as well as the different governmental structures in Virginia and the District of Columbia and the presence of multiple DoD installations in the region, BioWatch planning has been conducted at the Maryland state level, which he said has worked well. Unlike other BioWatch programs, a BAR in his program is declared at the state level, which triggers communication from the state level to the localities in Maryland and between the relevant state and federal agencies. He noted that developing the formalized, collaborative interactions among all of the agencies and levels of government was challenging and required addressing the nuances of preexisting working relationships.

Wendy Smith explained that her program is completely funded by a public health emergency preparedness grant. BioWatch program activities help Georgia meet the requirement for community preparedness, information sharing, early warning, and epidemiology. “I feel this program is essential to us achieving our objectives, and for our strategy for being prepared as a state and the metropolitan jurisdictions where BioWatch lives in Georgia,” said Smith. BioWatch exercises have been extremely beneficial to the program as they allowed it to engage the state agriculture department and emergency management agency in the BioWatch advisory committee. She also said that BioWatch activities have enabled the state to create a surveillance strategy for relevant infections in companion animals that enhances the state’s epidemiologic surveillance program.

Smith then discussed the planned third annual public health emergency response super exercise that will involve the state’s veterinary medical association’s members. This exercise will be based on having a national BAR event and notification of those members that there has been an intentional release. They will be asked to call a hotline to get information about the agent and to find out what to do if they are seeing sick animals in their practice.

In Massachusetts, the BioWatch program is run by the state health department, said Julia Gunn, who is a member of her jurisdiction’s advisory committee. Her employer, the city of Boston, brings to the table a horizontal network that unites the city’s health care community, should there be a need for that. She noted there has been a great deal of monitoring since the Boston Marathon bombing, including flyovers in the days preceding the marathon. She also explained that Boston has a biosafety officer and that research laboratories in Boston working with select agents and other high-risk pathogens are required to be permitted by the city health department and to report occupational exposures. Gunn called this a valuable program because otherwise it would be difficult to know who is working with what agents in her city.

As a scientist who studies bioaerosols, Mark Buttner said he is a BioWatch supporter who has seen the program go from receiving almost no interest to attaining total buy-in by the Las Vegas Health District. In fact, the reason why the BioWatch laboratory is at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, is that the previous public health officer was not interested in the program. Today, however, the new public health officer is fully engaged in the program and has worked to expand the BioWatch advisory committee. One result of this newfound enthusiasm for BioWatch in Las Vegas has been the development of a unified planning and response approach to emergencies and interagency cooperation among police, fire, and other agencies.

Buttner then explained that after a full-scale BioWatch training exercise in 2015, the Las Vegas BioWatch program issued a combined after-action

report and improvement plan. One result of that plan is that the Las Vegas BioWatch program has doubled its coverage and significantly increased the number of special events covered. Las Vegas BioWatch is also looking to engage Nellis Air Force Base.

With regard to involving military installations, Wireman said that when the San Diego and Los Angeles BioWatch programs held a joint exercise last year, the U.S. Marine installations in the region expressed strong interest in being part of that exercise. He suggested that his office at USNORTHCOM might be able to engage new partners, such as Nellis Air Force Base, by working through its connections to the branches of the military to encourage those installations to participate in the program. Wireman also noted that USNORTHCOM has joint regional medical operations officers that work with HHS regional emergency coordinators. Through their involvement in the BioWatch process, they are working together to develop a medical countermeasure plan for anthrax response. “There are a lot of intangibles you can get through the BioWatch program,” said Wireman.

DISCUSSION

Collaboration

Commenting on the presentations, John Vitko, Jr., said the consistent theme he heard was that BioWatch has served as a catalyst for enduring collaboration that did not develop with other public health issues. He wanted to know what was different about BioWatch that led not only to enduring coordination around BioWatch, but extended to other aspects of the panelists’ public health missions. Forzley replied that four Detroit area jurisdictions are represented on her BioWatch advisory committee, and BioWatch forced them to work together to write an emergency preparedness plan. In other emergency preparedness efforts, each jurisdiction created its own siloed plan that is similar to the others, but is carried out separately. She noted that the BioWatch collaborative experience is now spilling over to the region’s other preparedness efforts.

For Long Beach, one key driver of collaboration was the program’s strong connection to DHS. “Some of our local partners find it exciting to be part of something that is happening at the federal level,” said Wedgeworth. The other driver for collaboration was having the public health department actively soliciting input from all stakeholders rather than having public health tell stakeholders what was expected of them. This approach allowed each stakeholder to define what its role would be in addition to contributing to the emergency preparedness plan. “I don’t know any other time when we have been able to get this level of participation,” said Wedgeworth, who added that the stakeholders are now asking to be part of the BioWatch advi-

sory committee without having to be solicited to join. She noted, too, that other departments in DHS, including Critical Infrastructure, have offered to collaborate with the BioWatch advisory committee.

Romanosky commented that at the time BioWatch was first deployed public health emergency preparedness was in its infancy and revolved mainly around planning for pandemic influenza. “BioWatch was one of the factors that helped push the evolution of public health from the traditional disease surveillance paradigm to one that is more of a technology-based and forward-thinking-based paradigm of practice,” said Romanosky. He also credited BioWatch with helping the field evolve from planning for outbreaks of specific diseases to one that plans more broadly for emerging infectious diseases. Romanosky, like Wedgeworth, said BioWatch has encouraged greater collaboration and participation for federal partners, which in the National Capital Region has truly enhanced the capabilities of the local jurisdictions’ emergency preparedness response. He noted, too, that BioWatch’s approach to coordinated response planning is now being modeled by other programs, such as the Safe Cities Initiative and various radiation detection initiatives.

With regard to cooperation between law enforcement and public health, Romanosky said that BioWatch has helped trigger a paradigm shift in law enforcement’s attitude about public health personnel having first responder status and having a level of expertise that can be valuable. He also cited an example in which the connections made through the BioWatch advisory committee between law enforcement and epidemiology led to a joint investigation of an individual who had an unusual infection.

Gunn said that BioWatch has led to greater cooperation between public safety and public health in Boston, especially as new and emerging diseases evolve. “[Public safety] is now reaching out to us proactively for information and education,” said Gunn. One result of this closer relationship, she said, is that it has forced her department to think more broadly about how infectious diseases might enter her city. As an example, early in the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, she was asked what the risk would be to the harbor pilots who might board a tanker on which a crew member was infected. This question led to a great deal of planning and education with stakeholders she had never thought about, Gunn explained.

Funding

In response to a question about whether these new relationships between public health and law enforcement have led to increased funding for training exercises, Wedgeworth said that having law enforcement on board has not been beneficial yet in terms of direct funding, but it has enabled her program to participate in activities that would not have hap-

pened before. The fire department, for example, now considers BioWatch to be its partner in training of first responders. Pollok said that in San Antonio, funds for emergency preparedness from a variety of sources are now shared with public health for activities including and beyond BioWatch, such as how to respond to a life-threatening heat wave.

Pollok then noted that BioWatch in San Antonio benefits from already existing capabilities that serve other supported functions, such as laboratory equipment and emergency preparedness staff. BioWatch provides additional laboratory and field staff, and everything else is paid for from its federal emergency planning grant or from grants that its partners have. He noted, too, that his program so far has been able to weather reductions in the federal emergency preparedness planning grants. Romanosky added that budget cuts have reduced the amount of traveling and training for his program, but salaries and staffing levels have remained steady. He is, however, concerned that further funding cuts will start to negatively impact not only BioWatch but other public health emergency preparedness programs as well. He noted that there has been a steady reduction in public health staff in what he estimated to be 60 percent of the nation’s public health departments, and that entire programs, such as maternal and child health programs, have been completely eliminated at some facilities in Maryland. Communicable disease nurses, who would have played a critical role in a response to a bioterrorism incident, are completely gone in Maryland, he said.

Forzley said that the four medical directors and health officers on her BioWatch advisory committee are not funded by the federal emergency preparedness grant, but cutting staff who are funded by that grant is a real possibility for her program. “As that funding is cut we will be forced to pull them out of BioWatch because we have mandates and work plans that we have to adhere to for whatever is left in our grant dollars, and that is something we’re currently quite worried about,” said Forzley. Wedgeworth, echoing the previous comments, said that staff time is the critical issue when funding gets cut given that no personnel are dedicated solely to BioWatch. “There is going to be a new grant cycle coming out with the federal emergency preparedness program next year, and if there is a significant departure from the current focus, it is possible we will not be at liberty to dedicate our resources the way we have prioritized them so far,” said Wedgeworth.

Gerald Parker asked the panelists what would happen to their community preparedness and response capabilities if DHS had to terminate funding for BioWatch in 2017. Romanosky replied that “an important tool and data point would be taken away from us,” which he said would slow down the response to a biological agent release. For anthrax, this could mean the difference between life and death because there is a 24- to 48-hour period to get postexposure countermeasures to any exposed individuals. “If

you look at the pathophysiology and the clinical time line of these cases, I would lose my head start by not having BioWatch there to at least give me the idea that I need to start ramping up, depending on what the particular agent is that has been identified.” Pollok agreed with Romanosky’s assessment and said eliminating BioWatch would cut staffing in half because, currently, BioWatch and a CDC-funded laboratory response network support each other in San Antonio. Forzley said her program would lose crucial laboratory capacity and skills. “We can do planning, but [those skills] are not easily replaced and it is not something you can quickly drop in,” she explained.

Communication

Fluty asked Wedgeworth to describe the process her BioWatch advisory committee uses to communicate with her team in the event of a BAR in her community. After reiterating that the Long Beach advisory committee is distinct from the Los Angeles advisory committee, she explained that the two committees have regular quarterly meetings to coordinate plans and training exercises. At the local level, her team has developed a call script that it is now working through as a group to improve and it does routine notification drills to ensure that people are receiving notifications. She noted that as large as the Los Angeles metropolitan area is, she runs into her colleagues from the other BioWatch advisory committees often and participates in some of the same collaboratives.

In San Antonio, there are three different routes for communication, said Pollok. The laboratory first notifies him of a presumptive positive BioWatch sample, which gives him enough advance notice to prepare to trigger a broader notification. “Generally, when I get that presumptive positive, I’m letting our health authority know, our emergency management coordinator know, and my FBI coordinator know.” Once he receives confirmation, he goes through a short call tree that includes as many as eight people and sends out a predrafted email to which he adds specifics on the agent detected and how many monitors went off. He then directs the person who operates his city’s automated notification system to alert emergency management, public health, and all of the region’s hospitals.

Forzley said that coordinating cross-jurisdictional communications is still a work in progress because there are too many phone calls going back and forth. “We need to force ourselves to address some of that in our exercises,” she said. One challenge her program faced was that the state of Michigan’s emergency preparedness regions are not the same as BioWatch’s regions, but dealing with that challenge forced her program to cross those boundaries and develop better working relationships. Michigan, she noted, may now align its emergency preparedness regions with BioWatch’s based

on lessons learned from coordinating activities. In Boston, said Gunn, cross-jurisdictional communication takes on a different meaning because people fly into Boston to receive specialty medical care from places all over the world. For her, cross-jurisdictional communication can therefore span the nation or even the globe.

This page intentionally left blank.