APPENDIX C Estimating the Cost of Interventions: The Mother-Baby Package

The task of marshalling support for reproductive health care investments in reproductive health care is complicated by the resource constraints that face most developing country governments. Ideally, decisions about the mix and scale of reproductive health programs (like other public investments) should be guided by an enlightened form of cost-effectiveness analysis, with the costs being defined broadly so as to encompass all social costs, and effectiveness likewise defined broadly to include the dimensions of health, survival, and protection against unintended pregnancy. In practice, decisions have to be made with a great deal of uncertainty. As we have shown in the chapters of this report, there are large gaps in knowledge about the effects and costs of interventions and compelling reasons for thinking that results in different settings will vary widely.

In Chapter 7 we discuss results of an attempt by the World Bank to produce a set of cost-effectiveness comparisons for a broad range of health sector programs using a consistent set of estimates (World Bank, 1993). These estimates are useful, in our view, for highlighting areas where there are large differences between alternative forms of investment, rather than for detailed comparisons of narrowly defined interventions or for precise estimates of costs for a particular country. We called for further research on costs of interventions in different settings. In this appendix we illustrate one way in which the results of such research could be used in cost models for planning and budgeting in reproductive health. This exercise

also illustrates important limitations of the approach, given the data currently available or likely to be available in the near future.

The cost model discussed below was developed for one set of reproductive health interventions, known collectively as the Mother-Baby Package. The costs considered here are only public-sector costs—for example, there is no cost estimate for patient travel time—and even these estimates are subject to considerable uncertainty and would vary among settings. Nevertheless, we believe that it is useful to show how costs may be affected by elements of program design and scale.

As noted throughout the report, interventions vary considerably in the degree to which their effectiveness in developing countries is known. All the interventions included in the package have at least passed a minimal test of plausibility, that is, they have been judged by experts convened by the participating agencies to reduce a substantial amount of maternal/neonatal deaths or disability. In other words, the interventions embedded in the package make good sense, to judge from the clinical record, but that record has not yet furnished the numerical estimates needed for precise ranking.1

The data available do support an examination of the public-sector costs associated with the package's interventions and activities and enable us to determine the likely sensitivity of the cost estimates to changes in key assumptions. We believe that such calculations are informative and suggest promising directions for future research.

Throughout, we present hypothetical cost estimates that are built upon a series of assumptions. Apart from the published international prices of various drugs and supplies, there are few numbers that are based on empirical data. This exercise is not unlike a population projection in spirit. It is, in the end, no more than an extrapolation of assumptions. Its value lies in highlighting those assumptions that appear to be most critical and that therefore merit closest scrutiny.

THE MOTHER-BABY PACKAGE: OVERVIEW

The elements of the intervention package, described by the World Health Organization (1994), do not span the full range of reproductive health discussed in Chapters 2-5. Rather, they are focused on the events

and complications that surround pregnancy, delivery, and the postpartum period.

This focus on one segment of the reproductive lifespan, and the treatment of mother and child as a unit, have been proposed by the World Health Organization (1994:Table 3; also p. 11). The rationale is essentially that many complications of pregnancy and delivery for the mother are paired with complications that affect the child, at least in the case of neonates (see Chapter 5; see also Alisjahbana et al. [1995:Table 8]). For example, hemorrhage may bring on shock and cardiac failure for the mother, and this in turn may bring about asphyxia and stillbirth for the child. Some reproductive tract infections may induce premature onset of labor, and may also cause neonatal eye infections, pneumonia and the like.

In terms of service provision during pregnancy and labor, the package assigns the leading role to midwives. The World Health Organization (1994:18) describes the role of the midwife in this way:

The person best equipped to provide community-based, appropriate technology and cost-effective care to women during their reproductive lives is the person with midwifery skills who lives in the community alongside the women she treats. Midwives understand women's concerns and preoccupations. They accompany women through their reproductive lifespan, providing assistance at birth, then during adolescence, pregnancy and delivery, and providing family planning services when needed. Most interventions related to care of the mother and newborn are within the capacity of a person with midwifery skills.

Trained midwives are linked to other health personnel, and these personnel to each other, by a system of referral. Midwives and other first-stage health care providers diagnose the type of complication a woman is experiencing and gauge its severity. Depending on severity, they then direct her to the appropriate facility, which is either a health post, a health center, or a district hospital. The package as a whole is envisioned as a set of interventions to be undertaken within health districts, administrative units with average populations of 500,000.2

Care for neonates, in this package, consists of the following (World Health Organization, 1994:x):

All health workers (including TBAs), wherever they perform deliveries, will be trained to provide basic newborn care. They will assure clean

delivery, clean cord care and prevent ophthalmia neonatorum, ensure that the room in which the delivery takes place is warm, prevent hypothermia by immediately drying the baby and putting it in skin-to-skin contact with the mother, and initiate and support early and exclusive breast-feeding. Health workers will be trained to identify asphyxiated babies by assessing their breathing and heart rates and to resuscitate them by using appropriate equipment. Mothers and family members will be taught to care for their newborns at home (e.g., keep them dry and warm, protect them from cold and excessive heat, breast-feed them exclusively). For low birth weight babies, mothers will be taught the need for more frequent breast-feeding and the importance of keeping the baby warm. They will learn how to recognize newborn illnesses and where to seek help. Control of diarrhoeal diseases and of acute respiratory infections are important complementary strategies to reduce neonatal mortality.

Further discussion is provided in WHO (1994:51-56) on asphyxia, hypothermia, and ophthalmia neonatorum.

The other major form of intervention envisioned in the package is the delivery of family planning information and services on a postpartum basis and condom use for protection against AIDS and other STDs. Safe abortion services are not included in the package, although the treatment of abortion complications is considered. Postpartum family planning counseling includes support for breastfeeding (World Health Organization, 1994:57-59).

In sum, the heart of the Mother-Baby Package is a set of services including prenatal care, delivery care performed in most cases by trained midwives, treatment of complications for the woman or child or both, and the delivery of postpartum information on contraception and family planning services for the women who want them.

THE MOTHER-BABY COST MODEL

The public-sector costs associated with the Mother-Baby Package interventions have been estimated by Cowley and Bobadilla (1995), with further revisions by Cowley and Gamponia.3 All costs are expressed in 1992 U.S. dollars. Estimates of the costs of vaccines; disposables; supplies; information, education, and communication campaigns; refrigeration; transport; and some salaries were drawn from the Indian Child Survival and Safe Motherhood Project (Nirupam, 1993). Data on drug costs

were provided by Management Sciences for Health (Management Sciences for Health, 1992; Rankin, Sallet, and Frye., 1993). Capital costs are based on estimates by Herz and Measham (1987) and Tinker and Koblinsky (1993).

Health Posts, Centers, and Hospitals

As noted above, the Mother-Baby Package links trained midwives directly or through referral to three levels of the district health care system: health posts, health centers, and district hospitals. (In some country settings, three levels of health service delivery might not be feasible.) The clinical staffing of these facilities is set out in Table C-1.

A health post is typically staffed by a midwife who has been trained in aseptic delivery practices, as well as basic antenatal and postnatal care, and a nurse auxiliary. In the baseline costs model, the post is assumed to be capable of seeing as many as 10 patients per day. Although the staff of the health post are meant to attend all deliveries in its catchment area, the deliveries are assumed to take place in the patients' homes or in the homes of their midwives.

A health center is staffed by a registered nurse as well as a midwife and nurse auxiliary, and has access to a pharmacist, with a doctor available during daytime hours. Some centers are assigned to be equipped with a laboratory that can do selected tests and staffed by a part-time technician. The center can treat as many as 18 patients per day. Among women who go to a center, most of their deliveries take place in the center.

A district hospital is staffed by full-time nurses and primary care doctors with specialists available on an as-needed or part-time basis. The hospital is equipped with X-ray and other equipment, most of the usual laboratories, has some microbiological capabilities, and employs a full-time lab technician.4 It has 29 beds devoted to maternity care. Among women who go to the hospital, all deliveries are assumed to take place in the hospital.

As discussed above, the baseline model allows some members of the clinical staff, and all other personnel, to be available to address other health needs not included in the package. The assumption of the baseline model is that, apart from certain clinical personnel whose is assumed to be fully devoted to the package (midwives, obstetricians, and nurseauxiliaries),

TABLE C-1 Assumptions Regarding Clinical Staffing in Rural and Urban Baseline Models of Mother-Baby Package

|

Clinical Staff |

Health Post |

Health Center |

Hospital |

|

Nurse Auxiliary |

1a |

2a |

6a |

|

Pharmacist |

|

1 |

1 |

|

Midwife |

1a |

2a |

2a |

|

General Physician |

|

1 |

1 |

|

Obstetrician |

|

|

1a |

|

Lab Technician |

|

0.25 |

1 |

|

Education Specialist |

|

|

1 |

|

Registered Nurse |

|

1 |

5 |

|

Nurse Anesthesiologist Respiratory Therapist |

|

|

1 |

|

X-ray Technician |

|

|

1 |

|

Pediatrician |

|

|

1 |

|

Total |

2 |

7.25 |

21 |

|

NOTE: The percentages assumed to be devoted to the package vary by type of facility: for health posts, 75 percent of time is devoted to the Mother-Baby Package; for centers, 50 percent, and for hospitals, 30 percent (see also Table C-4). In the case of health posts, all clinical personnel are fully devoted to the Package, but support personnel and other facility-level resources are not. |

|||

|

a Staff are fully devoted to the package. |

|||

some 25 percent of health post staff time and other resources are available for other uses, as much as 50 percent of health center time and resources, and 70 percent of hospital staff time and resources. 5

Diagnosis and Referral

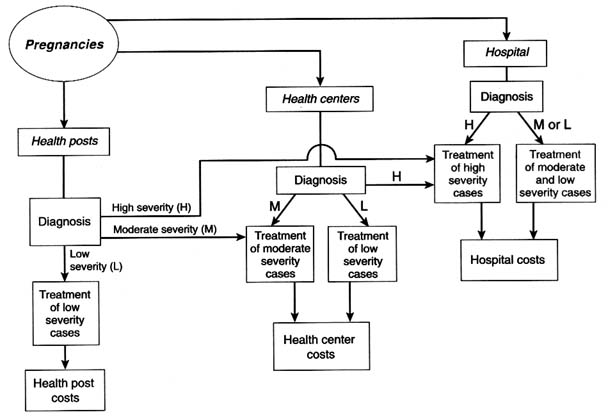

Figure C-1 shows the system of diagnosis and referral that is envisioned in the Mother-Baby Package cost model. In this model, diagnosis and referral is dependent on a set of assumptions regarding probabilities of complications; these are presented in Table C-2 by type of condition.

The baseline model assures that most pregnant women contact a trained midwife who is linked to the local health post. Some women will go to the nearest health center as walk-in patients for prenatal care and delivery, and, likewise, a few will go directly to the district hospital. At

|

5 |

The baseline model examined here departs from the Cowley-Gamponia model in assuming that the clinical personnel just mentioned are devoted full-time to the package activities; see Table C-1. |

TABLE C-2 Assumptions Regarding Conditions, Severity, and Referral in the Rural Baseline Model: in percent

|

|

|

Of those with condition, severity level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

High |

|

|

Type of Condition |

Pregnancies with the Condition |

Low |

Moderate |

No Surgery |

Surgery |

|

Abortion complications |

2 |

90 |

0 |

7.5 |

2.5 |

|

Anemia |

30 |

50 |

30 |

20 |

0 |

|

Reproductive tract infection |

2 |

50 |

30 |

20 |

0 |

|

Eclampsia or hypertensive disorder |

5 |

20 |

50 |

22.5 |

7.5 |

|

Hemorrhage |

10 |

20 |

50 |

22.5 |

7.5 |

|

Obstructed labor |

5 |

20 |

50 |

22.5 |

7.5 |

|

Sepsis |

8 |

20 |

50 |

30 |

0 |

|

NOTE: Low severity cases are treatable at all levels; moderate severity cases are treatable at a health center or hospital; high severity cases are treatable only at a hospital. |

|||||

all facility levels, the existence of a potentially threatening condition for the woman is diagnosed, and an assessment made as to the severity of the condition. Mild severity conditions can be treated at any level of the system; moderate severity conditions can be treated only at the health center or hospital; and high severity conditions (some of which demand surgery) require treatment at the hospital. The diagnosis that decides such referrals is based on clinical observation only. For simplicity, the baseline model does not include an allowance for inappropriate referrals or for women who do not show up at the facility to which they have been referred, but these complexities can be added without changing basic results.

The assumptions about family planning information and service delivery are also somewhat artificial. As shown in Tables C-3 and C-4, the baseline model assumes that 15 percent of pregnant women will want to space or limit their next births. This figure is taken to be a constant and is not linked directly to the expenditures in the Mother-Baby Package on information, education, and communication efforts. The method mix is assumed to vary among facilities, with more clinical methods being delivered in the higher level facilities. In view of the leading role played by trained midwives in the Mother-Baby Package, it would be particularly important to refine estimates of training costs. Those used in the baseline

TABLE C-3 Assumptions Regarding Family Planning Use in the Rural Baseline Model: in percent

|

Of women wanting to space or limit births and presenting to |

Condom |

Oral Contraceptives |

IUDs |

Injectable |

Tubal Ligation |

|

Health Post |

25 |

50 |

|

25 |

|

|

Health Center |

10 |

50 |

25 |

15 |

|

|

Hospital |

5 |

50 |

25 |

10 |

10 |

|

NOTE: Of all pregnant women, 15 percent are assumed to want to space or limit births, following information, education, and communication exposure; see Table C-4. |

|||||

model are derived from cost studies by the MotherCare Project in two Nigerian states (Koblinsky, personal communication). All these simplifying assumptions would have to be modified in a rigorous analysis of cost-effectiveness for a particular setting.

Allocating Facility-Level Costs Across Activities

A key task for cost models is the distribution of costs of fixed inputs across various program outputs and services. For this model, these shared costs include salaries of clinical and support staff, infrastructural services, management, and transportation.

We can illustrate the approach using the example of a woman who appears at the health post and is not referred to the health center or hospital. Let k index the type of service required by the patient. A woman may require more than one type of service, such as delivery care plus treatment of complications plus postpartum family planning services. Let

Further, let

Then for a post operating at full capacity,

TABLE C-4 Major Miscellaneous Assumptions in the Rural Baseline Model (Not Otherwise Presented in Tables C-1 to C-3)

|

Factor |

Assumptions |

|

Information, Education, and Communication |

Advertising undertaken by both posts and centers; this plus outreach and audiovisuals occur at the district hospitals. To each health post some $6,010 is devoted; to each center, $4,250; and to each hospital, $5,500.; These expenditures do not affect the demand for family planning or other services at a particular facility. |

|

Demand for Services |

The crude birth rate (CBR) = .042; the crude pregnancy rate is 10 percent higher than this.; Some 15 percent of pregnant women wish to space or avert entirely their next birth. No explicit link is made between the CBR and the demand for family planning or between the CBR and actual family planning use by method.; 80 percent of pregnant women are attended (covered) by package-supplied personnel and services. Of these, 85 percent present to health posts for prenatal care and normal (uncomplicated) delivery; 12 percent present to centers and 3 percent to hospitals. |

|

Diagnosis and Referral |

Diagnosis is on the basis of clinical observation only; no other resources are involved.; The existence of a condition and its severity level are correctly diagnosed; no inappropriate referrals occur. Referred patients always arrive at the facility to which they were referred.; Some 12 percent of births require neonatal management. |

|

Initial Staffing and Resource Levels |

None of the resources required for package are treated as sunk costs. Assumption is that long-run average costs equal marginal costs (whether supplies, clinical and support personnel, or additional infrastructure, management and transportation). |

|

Training |

All training costs are allocated to the district as a whole, not separately to hospitals, centers, or posts.; District-level site preparation, cost of $16,000, one-fifth of the estimated total cost. Training will take place at the provincial level, each province having five districts. The depreciation period is 10 years.; The total number of midwives required in the district is calculated, then the number of master trainers is derived on the assumption that 10 midwives can be trained by each master trainer. Training costs are $500 per master trainer and $125 per midwife. The depreciation period is 5 years. |

|

Facility Capacities |

One health post can engage in a maximum of 10 patient contacts per day, for 240 days per year. Effective capacity, however, is only 82 percent of this maximum. |

|

Factor |

Assumptions |

|

|

One health center can provide a maximum of 18 patient contacts per day, for 240 days per year. Effective capacity is 85 percent of the maximum.; One district hospital can accommodate 29 beds per day, for 365 days per year. Effective capacity is 95 percent of the maximum. |

|

Transportation |

Each health post has a bicycle; each center, two-way radios, bicycles, a motorbike, and a claim on one-fourth of a jeep and driver; four centers will share the vehicle; each hospital has radios, bicycles, a jeep, and an ambulance, plus $2,500 per year in transportation subsidies. |

Let W = total clinical salaries at the post. Now since it is identically true that

it seems reasonable to apportion total clinical salaries W into components ak that are specific to types of patients, where

We can then view the product Ykak as the clinical salary costs associated with all patients of type k at a given post. This amounts to an allocation rule whereby (short-run) fixed costs, such as salaries, are allocated across patient types in proportion to the number of clinical contacts required. Similar expressions, differing only in what is assumed about the required clinical contacts ck and capacity C, apply to centers and hospitals. For costs of nonclinical staff, infrastructure, and services, costs are distributed across patients of various types in proportion to the required clinical contacts.

The baseline cost model provides estimates of total costs assuming that posts, centers, and hospitals operate at their full effective capacity (Table C-4). In determining the required number of posts, centers and hospitals, the model takes into account only the number implied by the Mother-Baby Package in conjunction with the assumed demographic characteristics of the district.

HYPOTHETICAL COST ESTIMATES

We begin by describing the implications of the baseline model of a low-income rural area and vary the parameters of that model to explore the impact on total costs. We then turn to a second baseline model that is meant to represent a middle-income and more urbanized area.

Total Costs: Rural Baseline Model

The baseline cost estimates suggest that for a district of 500,000 population, with 80 percent of pregnancies covered by the package services, annual total costs would be $1,500,000 (in 1992 U.S. dollars). Of this total, some $740,000 is expended at the health post level, $360,000 at the health clinic level, and $420,000 at the level of district hospitals. The total estimated costs for the Mother-Baby Package are thus just over $3 per person per year. Given a total of 23,100 total pregnancies, 80 percent of which are covered by the package, the cost per pregnancy is $66. The cost per attended pregnancy, of which there are 18,480, is $83. The package is supported by training activities for midwives; on an annual basis this requires $4,600 per district. The required number of health posts is 59; some 11 centers are required, and a total of 3 district hospitals.

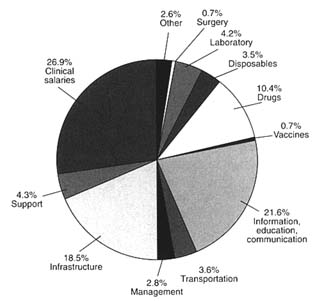

Figures C-2 and C-3 provide breakdowns of costs according to type of cost and patient condition. Figure C-2 shows that the two largest areas of expenditure are clinical salaries, 27 percent of the annual budget, and information, education, and communication 22 percent. Infrastructure is also an important item, accounting for 18 percent. This percentage reflects assumptions about the lifespan of infrastructure: straight-line depreciation is used to convert initial construction or purchase costs into annual figures.

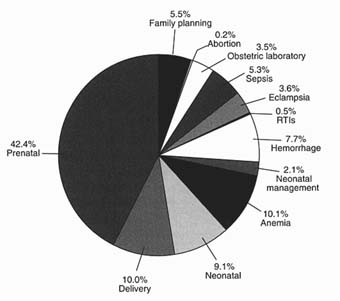

Figure C-3 shows the use to which these services are put: some 42 percent of expenditures for prenatal care, 10 percent for normal delivery care, and 9 percent to normal neonatal care. These services are supplied for all pregnancies and births. Postpartum family planning services take up 5.5 percent of the budget. The remaining service costs shown in Figure C-3 reflect the incidence and severity of pregnancy-related complications as well as the clinical and variable resources required to treat such complications. For example, anemia treatment occupies just over 10 percent of the annual budget, and treatment of hemorrhage some 8 percent.

Sensitivity Analyses

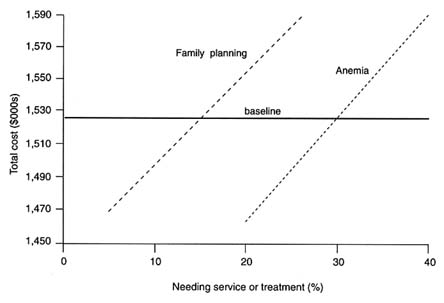

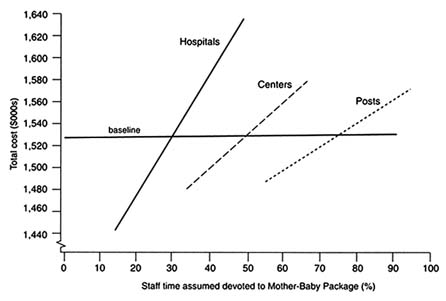

Figures C-4 and C-5 show how the incidence of particular conditions affects total costs. Here the baseline level of total costs, $1.5 million, is the

horizontal line. For each condition, the probability of occurrence is varied in a range around the baseline value given in Table C-3. For example, in the baseline the percentage of pregnancies with hemorrhage is assumed to be 10 percent. We assess how total costs vary as this percentage is varied over the range from 5 to 15 percent. The result is shown in the dotted line in Figure C-4. Note that the distribution of hemorrhage severity is not altered during the calculations, only the likelihood that a hemorrhage occurs.

Changes in the incidence of abortion complications, RTIs, and neonatal complications appear to exert rather modest effects on total costs. By contrast, changes in the incidence of eclampsia and obstructed labor, hemorrhage, and sepsis have much larger effects on costs. This is important for projections of costs of safe pregnancy and delivery care because, as Chapter 5 shows, there is considerable uncertainty about the incidence and prevalence of these conditions.

Figure C-5 shows the result of similar calculations for the incidence of anemia and also presents the cost implications of changes in the level of demand for family planning. Changes in anemia incidence and family planning demand exert considerable influence on total costs.

The role of assumptions about joint costs is explored in Figure C-6. Recall that in the rural baseline model, it is assumed that certain staff—obstetricians,

FIGURE C-6 Total costs by joint cost assumptions.

midwives and nurse auxiliaries—are devoted full time to package activities. Support staff, however, and services such as transport and infrastructure, are not fully charged to reproductive health care and are available for other health care needs. At the health post level, the assumption in the baseline model is that 75 percent of support staff, transport, and infrastructure are devoted to package activities; at the center level, 50 percent; and at the hospital level, 30 percent. These assumptions about joint costs prove to be critical in estimating the total costs of the Mother-Baby Package since the costs shared with other health care needs are a large proportion of the total. Especially at the hospital level, assumptions about joint costs have a strong impact on the total estimated costs of the Mother-Baby Package.

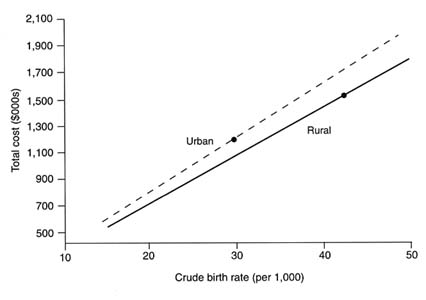

Model for an Urban Population with Lower Birth Rate

The rural baseline costs can be compared with estimates for a moderate-income urbanized area. The principal differences in the urban model are in the following assumptions: the crude birth rate is 30 per thousand, as compared to 42 in the rural baseline; the proportion of postpartum women wishing to use family planning is 25 percent, compared with 15; and the prevalence of RTIs is 5 percent rather than 2 percent; see Table C-5. In addition, a higher proportion of women are assumed to use centers and hospitals for prenatal and delivery care, 40 percent, compared with 15 percent in the rural model. Personnel costs, however, are assumed to be the same as in rural areas; this assumption would not hold in many health services. We also incorporated lower costs for vehicles, assuming that clinics in densely populated areas would rely less on mobile services.

These differences in assumptions have clear implications for total costs. For an urbanized district of the same population size, 500,000, as

TABLE C-5 Urban Baseline Model: Differences in Assumptions

|

Factor |

Assumptions |

|

Demand for Services |

The crude birth rate = .030.; Some 25 percent of pregnant women wish to space or delay their next birth.; As with rural model, some 80 percent of pregnant women are attended by package-supplied personnel and services; but of these, 60 percent present to health posts for prenatal care and (uncomplicated) delivery, 30 percent to health centers, and 10 percent to hospitals.; 5 percent of pregnant women have RTIs or STDs. |

FIGURE C-7 Total costs by crude birth rates, rural and urban.

the rural district modeled above, the total costs of the package are estimated to be $1.2 million, about 80 percent of the costs for the rural district. On a per capita basis, the urban costs are $2.46; this translates to $75 per pregnancy and $93 per attended pregnancy. The urban-rural cost differences are mainly attributable to the smaller number of pregnancies. The difference in crude birth rates is partly offset by a greater demand for family planning services in urban areas, by greater incidence of RTIs and STDs, and by the greater use of centers and hospitals.

These urban-rural differences are depicted in Figure C-7, which indicates that at a given level of the crude birth rate (on the horizontal axis), urban total costs exceed those for rural areas. The baseline urban and rural cost estimates, which use different crude birth rates, are shown in the two dots.

REFERENCES

Alisjahbana, A., C. Williams, R. Dharmayanti, D. Hermawan, B. Kwast, and M. Koblinsky 1995 An integrated village maternity service to improve referral patterns in a rural area in West Java. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 48(Supplement):Table 8.

Chalmers, M.E., M. Enkin, and M. Keirse, eds. 1989 Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Cowley, P., and J.L. Bobadilla 1995 Costing the Mother-Baby package of Health Interventions. Population, Health, and Nutrition Department, World Bank, Washington, D.C.

Herz, B., and A. Measham 1987 The safe motherhood initiative: Proposals for action. World Bank Discussion Paper No. 9. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Management Sciences for Health 1992 The International Price Indicator Guide, 1991. Boston: Management Sciences for Health.

Nirupam, S. 1993 Child Survival and Safe Motherhood Project Costs in India. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Rankin, J.R., J.P. Sallet, and J. Frye 1993 International Drug Price Indicator Guide, 1992-93. Arlington, Va.: Management Sciences for Health.

Tinker, A., and M. Koblinsky 1993 Making Motherhood Safe. World Bank Discussion Paper No. 202. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

World Bank 1993 World Development Report 1993: Investing in Health. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

World Health Organization 1994 Mother-Baby Package: Implementing Safe Motherhood in Countries . Geneva, Switzerland: The World Health Organization.