4

Workshop Two, Part Two

OPENING REMARKS

Workshop series co-chair Lt. Gen. Michael Hamel (USAF, ret.), independent consultant, welcomed participants to the second day of the second workshop in the series. He explained that the forthcoming panel presentations would highlight the essential dynamics for transformation from an organizational standpoint. Achieving such dynamics makes it possible for transformation efforts to gain traction and for the transformation mindset to become the new normal way of conducting business.

OUT-OF-THE-BOX LEARNING: PANEL ONE

Mr. Gerald J. Caron III, Chief Information Officer, Office of the Assistant Inspector General for Information Technology, Office of the Inspector General, Department of Health and Human Services, explained that zero trust offers a different approach to cybersecurity. Although many people talk about zero trust, they may not really understand what it requires and thus may not be achieving that level of security. He added that many vendors contribute to zero trust, but no single vendor does zero trust. As a result, vendors are beginning to form partnerships to enable zero-trust architectures.

Mr. Caron compared legacy networks, most of which are architected as flat networks, to Tootsie Roll Pops, with a “hard outer shell with a soft, gooey center”—once adversaries find an opening in the perimeter security, they can leverage vulnerabilities and gain full access. Many efforts have been made to prevent such breaches, but, referencing Frederick the Great, he said that “he who defends everything defends nothing.” He asserted that trying to protect all systems, applications, and data equally leads to a situation in which some are overprotected, others are underprotected, and overall network functionality is constrained. Instead, the optimal approach to cybersecurity is to determine where protections are needed based on the

sensitivity and associated risk of individual components. Because zero trust assumes that all users and devices pose a threat, it protects against both outsider and insider threats, if done correctly.

Mr. Caron emphasized that zero trust revolves around the need to protect data. He shared the five core principles of zero trust: (1) know the users and devices, (2) design systems assuming that they are all compromised, (3) use dynamic access controls, (4) constantly evaluate risk, and (5) invest in defenses based on the classification levels of the data. He underscored that zero trust is not a tool; it is an architecture. In order to protect data, it is critical to understand what and where they are. Data need to be properly categorized in terms of threat vectors and the related level of risk based on sensitivity (i.e., not all data are equally important). It is also critical to know where the data are going and how they are being accessed. Because some system owners do not understand their data flows (i.e., how data are moving from Point A to Point B), he suggested creating a baseline that highlights what is normal, and, even more importantly, when activity is abnormal and action needs to be taken.

Network segmentation, with its use of firewalls and perimeters to group like applications together, is a common approach to security; however, zero trust is a much more granular approach to segmentation in which applications and databases may be segmented (i.e., microsegmentation of data). He explained that the groupings are based on function, not physical location, and protections are tailored to the data’s sensitivity and mission criticality. Many other factors are critical for zero trust, such as different levels of risk related to identity (e.g., an on-site, cleared government employee has less risk than a vendor partner with a lower-level clearance). Zero trust considers the user’s role and location, the state of the device, and the type of data or services being accessed. He stressed that seeking security compliance is insufficient: security effectiveness is key.

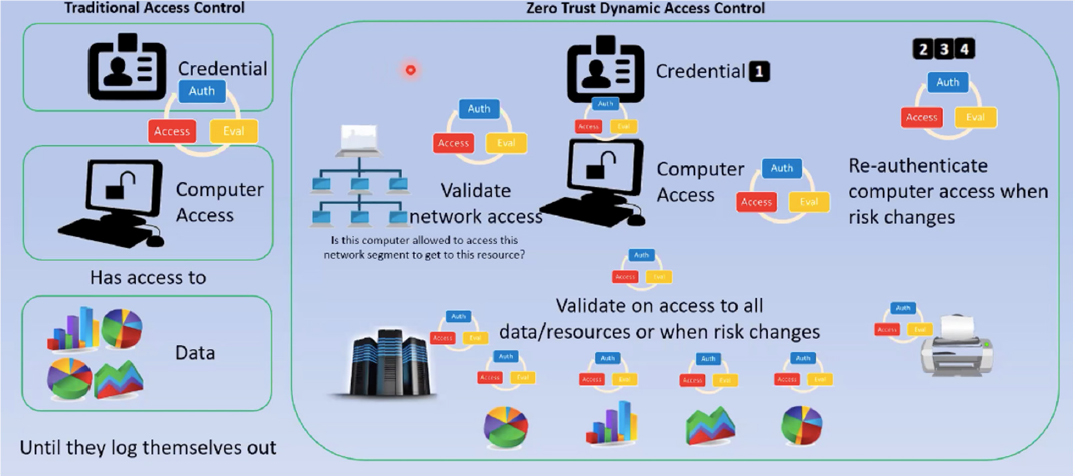

Mr. Caron noted that zero trust also offers dynamic access control. Instead of providing authentication only once at the start of a user’s session, zero-trust authentication is ongoing and allows only the right access to the right data at the right time by authenticating each time new data are accessed and each time a change in risk is triggered (see Figure 4.1). To better describe dynamic access control, he provided an analogy to a movie theater experience: instead of scanning a ticket in the lobby and allowing patrons to enter as many individual movie screenings as desired, the ticket would be scanned directly at the entrance to each movie screening, and ushers would check tickets again inside so that people only view the one movie for which they paid.

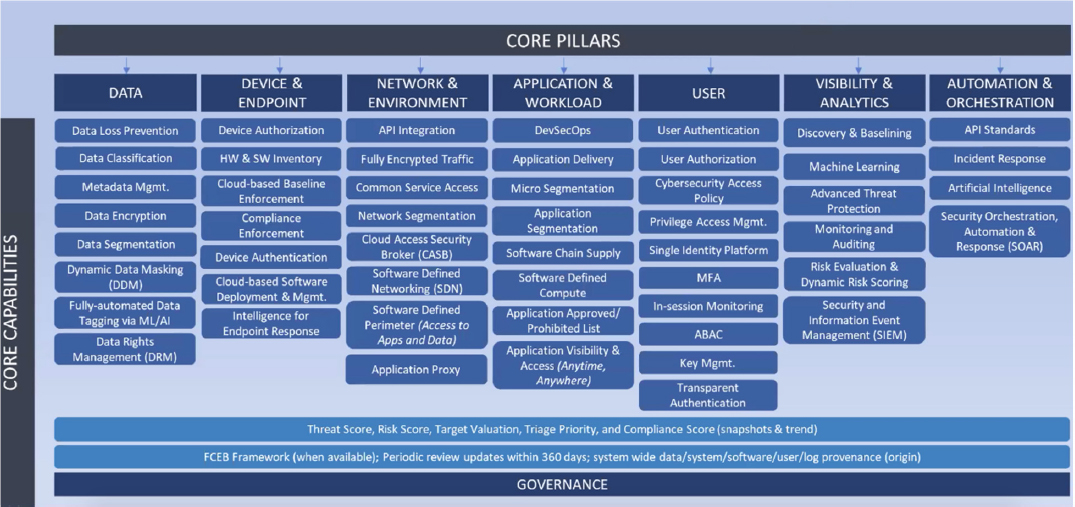

Zero trust also assesses the state of each device attempting to access the network to ensure that the client does not introduce additional risk to the environment. Continuous monitoring is a key aspect of zero trust; real-time data collected during this monitoring can be linked with known threats and data/system sensitivity to drive cyber protections. Mr. Caron highlighted the most significant advantage with zero trust: it is an integration effort (as opposed to the stovepiped approach of the past) that connects factors to determine a dynamic risk score (based on risk tolerance and the methodology to classify the data that need to be protected) and determine appropriate protective action. In closing, he shared a zero-trust capabilities framework, which helps to conduct an inventory of all capabilities and illuminates where gaps exist (see Figure 4.2). Workshop Two chair Dr. Pamela Drew, former executive vice president and president of information systems, Exelis, remarked that this framework would be a useful exercise for the Air Force to assess its data infrastructure.

Dr. Christopher Chute, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Health Informatics; professor of medicine, public health, and nursing; and chief health research information officer, Johns Hopkins University, discussed digital medical records and data governance. He suggested that the Air Force take advantage of digitization’s opportunities to enable analysis, interpretation, and discovery as a means to continuously improve the infrastructure, processes, and methods of its operations moving forward. He proposed that the Air Force develop an organization similar to that of the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology to facilitate data governance across the enterprise.

He explained that lessons about data governance could be applied from the past four decades of health information technology. For example, in the past, healthcare organizations had severe data fragmentation, few standards, and no interoperability specifications. Data governance in healthcare began with the creation of large entity relationship diagrams for relational structures to normalize data within an enterprise. However, this approach was unsustainable. He emphasized that a large master schema of all data in a relational context across the Air Force is not needed. Instead, he suggested a more modern approach that focuses on managing the important elements (e.g., the processes, activities, statuses, and outcomes) in an object framework.

Dr. Chute articulated that healthcare data are expected to be FAIR: findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable. Interoperable data are comparable (to draw conclusions) and consistent (i.e., people

throughout the organization use the same processes). He emphasized that interoperable objects require a dynamic infrastructure that will continuously improve and add new dimensions and components. The comparability and consistency allow for a “graceful evolution” of these objects, which can be related to other objects for inference and analysis.

He described two dimensions of having governance around an object or element: (1) syntactic (i.e., how to structure objects and elements, and having significant associated metadata to interpret and make sense of them) and (2) semantic (a formalized and reproducible way of managing vocabulary, names, tags, and identifiers so that they can be reconciled). Healthcare organizations seek to identify “off-the-shelf” ontological frameworks and schema, which increases interpretability across the broader healthcare community. However, not knowing fully what kind of data the Air Force has to organize and integrate, he was unsure whether it would practical for the Air Force to consider externalized standard resources. He emphasized that however the approach is structured in the Air Force, a coordinated, centralized data governance activity with decision-making authority is essential.

Dr. Chute explained that once (1) there is a catalogue of elements, functions, activities, outcomes, and statuses that are relevant to the Air Force enterprise; (2) a syntactic structure has been defined for each object; and (3) the elements of those syntactic layers have been populated with significant data types that are reproducible, the next step is to consider how the objects are connected (i.e., graph relationships, semantic relationships). If left ungoverned, however, this process can consume an entire organization with diminishing returns. Thus, he said that part of the data governance process is making rational decisions about the level of granularity needed to prioritize activities. He described the “sweet spot” as identifying enough data governance to enable the enterprise to sustain, manage, and scale the desired level of inquiry and discovery—enterprise-level digitization cannot happen with any efficiency without careful attention to data governance.

Mr. Michael Pack, founder and director of the Center for Advanced Transportation Technology Laboratory (CATT Lab), University of Maryland, discussed lessons learned while working with public safety and transportation officials to digitize and make sense of their data. Founded in 2002, the CATT Lab is comprised of more than 75 data scientists, software developers, designers, program managers, and IT and network engineers, as well as students and affiliated researchers, who build and deploy data analytics tools to manage, integrate, and archive these large data sets.

Mr. Pack explained that the transportation industry has many disparate systems; each department has deployed their own data sets and data collection technologies for their own individual use cases (e.g., travelers might see a light pole with several different sensors from several different agencies all collecting the exact same information). In addition to traffic data, there are weather data from ground-based weather stations, computer dispatch data from first responders, crowdsourced data from Waze usage, data from media reports, data from maintenance vehicles, data from traffic cameras, and data from cell phones. Yet, he emphasized that no one has a complete picture of what is occurring on the roadways, and there is a lack of situational awareness. Furthermore, data collected by individual departments for specific purposes are often used only in real time and then discarded instead of being archived for later use in planning decisions and after-action review. To eliminate this waste, the CATT Lab was asked to fuse these data to make them more readily accessible and usable by all of the different departments of transportation. Doing so would cut down on digital waste and excess spending. He underscored that data are only worth archiving if they are easily understandable for, usable by, and accessible to managers, decision makers, users, and applications. Because most users are not data experts or computer scientists, the CATT Lab builds compelling visual analytics tools (i.e., user interfaces) that simplify data access and increase buy-in for data sharing.

The CATT Lab has now built more than 50 data analytics platforms used by ~14,000 people in the United States. Mr. Pack provided an overview of a multi-agency common operational view of the roadways, which was created by fusing disparate data. This system is operational nationwide, with billions of data points and measurements collected in real time that are archived indefinitely. For example, when a crash occurs, it is possible to collect data on the locations of the first responders, on the number of lanes blocked, and from radio systems in the area. There are also videos being captured of the scene from the ground (e.g., dashcams) and from the sky. Cellular telephones and connected vehicles also provide a substantial amount

of data to the CATT Lab’s efforts (e.g., people using weather apps or map apps on their phones are contributing to the data samples). He emphasized that the data being collected from vehicles (e.g., using indications of traction control engagement to understand a situation on the roadway) are privacy-protected in certain ways. There are also tens of thousands of streaming closed-circuit television cameras on the ground, in police cars and maintenance vehicles, in the sky, and in bus stations that are collecting data. With the help of image and video processing capabilities, it is possible to predict where vehicles are going as they are tracked from one camera to the next.

Most of the CATT Lab’s analytics are after-action review analytics or planning analytics to help people determine what to invest in or where to move assets to respond to a specific incident. In closing, Mr. Pack described several challenges the CATT Lab has faced with its data analytics tools:

- Scalability. With a limited budget, it is critical to optimize and try to predict user requests, so as to have data precomputed to lead to solutions more quickly.

- Normalization. Although there might be hundreds of sensors collecting information at different time intervals, all of the data ultimately have to look somewhat similar for the user to be able to use them to answer a question.

- Ever-changing data landscape with new technology and new sensors.

- Private sector competition with the public sector. The CATT Lab has to be aware of private sector data sets and be able to fuse them with public sector data sets. Issues with acceptable data use terms and conditions can arise during this fusion.

- Protection of people’s privacy.

- Ease of access and usability with the development of compelling user interfaces.

- Creation of buy-in by convincing agencies to share data, with analytics that answered a question posed by someone of a senior level in the agency.

- Sustainable funding strategies.

Open Discussion

Dr. Drew observed that despite its challenges, the CATT Lab has successfully gathered, normalized, and scaled data. She asked about the framework used to integrate each data set and to build analytics. Mr. Pack said that when the CATT Lab first started to develop analytics tools, it built a common schema and expected agencies to provide their data in that format. Because no agency had the funding to convert their data, that approach was ineffective. Now, the CATT Lab accepts data in whatever format or transmission method the agencies choose, and an internal team is dedicated to the standardization and fusion of those data. Multiple review processes with the agencies ensure that data are mapped and fused appropriately, and an art and usability team is dedicated to continuous iteration and testing of the user interface. He emphasized that it takes a significant amount of time to normalize data (e.g., it could take several months to ingest one data set). Dr. Drew described this as a positive example of the centralized data governance concept championed by Dr. Chute.

Reflecting on the CATT Lab’s indefinite date retention policy, Dr. Julie Ryan, chief executive officer, Wyndrose Technical Group, asked how it manages both the volume of data over time and the challenges of media degradation and technology migration. Mr. Pack noted that this data retention policy emerged because it was more costly to reintegrate data than to store them indefinitely. Technology migration, however, is expensive and can inhibit growth; it is difficult to keep pace with the changing technology and the need to convert systems. In response to a question from Dr. Drew about the size of the CATT Lab’s data set, Mr. Pack replied that it is many, many petabytes, and growing daily. He added that Amazon Web Services is only used for backups; the CATT Lab found it more cost effective to build its own private cloud to host these data. Gen. James (Mike) Holmes (USAF, ret.), senior advisor, The Roosevelt Group, asked about the CATT Lab’s processes for cleaning and presenting data. Mr. Pack explained that some of the data

(e.g., incident data) cannot be cleaned; if the CATT Lab over-cleanses certain data sets, it obfuscates the truth of the data and could cause problems for the users. Therefore, the CATT Lab provides a visual overview of the entire data set, with the ability to zoom, filter, and view details on demand. Cleansing tools such as filters can be applied to user interfaces, however, to eliminate data that are likely suspect. When multiple data sets describe the same event in a different way, he continued, fusion becomes significantly more challenging. Dr. Marv Langston (USN, ret.), independent consultant, pointed out that Alabama has put all of the state’s data on Google Maps (“Virtual Alabama”), and he asked Mr. Pack about using a similar approach to make data available. Mr. Pack responded that the CATT Lab has some secure data that cannot be made publicly available. He emphasized that the CATT Lab’s system is a true fusion and analytics platform (as opposed to an open data.gov system) that helps people to address difficult problems.

Lt. Gen. Hamel inquired about the current status of zero-trust frameworks within the Department of Defense (DoD) and other large government agencies. Mr. Caron said that although he has yet to see a full implementation of zero trust, many of the agencies are pursuing that path. He suggested that agencies begin by developing a “playbook” to determine all of the key players and resources. He added that President Biden’s May 2021 Executive Order on Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity emphasized zero trust, and all agencies in the Executive branch were required to submit their plans for zero trust within 60 days of the executive order. The Air Force in particular has taken a step toward zero trust at the enterprise level. He mentioned that the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s National Cybersecurity Center of Excellence is developing a proof of concept for zero trust. He reiterated that because zero trust is a new way of thinking, it requires a culture change. Dr. Drew asked if any agencies have prioritized their most important assets in need of protection. Mr. Caron acknowledged that while progress is being made, this as an ongoing challenge, particularly when assets are miscategorized owing to a lack of information. Because it is usually the IT staff who are focused on zero trust, it is often viewed as a “technical” issue. However, the technology is the easy part; the integration, policy changes, identification of risk tolerances, baseline creation, and inventory of owned assets are difficult. To be effective (instead of merely compliant) in cybersecurity, he continued, these non-technical elements have to be prioritized.

Gen. Holmes asked how encryption and other advanced technologies relate to risk mitigation. Mr. Caron advocated for advanced encryption but noted that adversaries are leveraging the same technologies (e.g., quantum computing) as the United States—and the U.S. government is behind the competition. He explained that if security is so restrictive that it reduces performance, people will find ways to work around it. Instead, government agencies need to adopt an approach that is simultaneously sustainable, secure, and supportive of the mission.

Dr. Langston wondered how data governance forces a data schema across an organization as large as DoD and whether the medical field has a common schema. Dr. Chute noted that for many years, the healthcare industry did not have a centralized structure or coordination across its organizations. After the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) was stood up in 2004, incremental details of information would be requested to be comparable and consistent across organizations. It was not until 2020 that the 21st Century Cures Act required electronic health record vendors and other organizations to conform with ONC specifications (i.e., common ways to exchange medications, laboratory results, and diagnoses). Each year, the ONC publishes an updated U.S. Core Data for Interoperability. He emphasized that common schema are enabling national-level data aggregation and integration in healthcare. He recognized that the process takes time but added that there are precedents in this and other large-scale industries that prove it is evolving. He suggested that the Air Force could begin with an ontological characterization of “things that fly,” for example, and then delve into specific models. Each has metadata that are updated in near real time (e.g., flightworthiness, repair status), and dashboards could be used to make inferences about range of force projection, for instance. The goal is to begin with relatively discrete, achievable, feasible characterizations; create buy-in across the community on those assets and elements; and demonstrate the resulting value to the community. Confirming the feasibility of this approach for the Air Force, Dr. Drew shared an anecdote about when Boeing bought McDonnell Douglas, part of Hughes, and part of Rockwell International Corporation. Each of those companies had its own technical library and librarians who had created indices

of reference documents. Those indices were used to create knowledge bases and a searchable ontology that became the core of the search engine, which became a unifying force for all four companies.

Dr. Annie Green, data governance specialist, George Mason University, added that data governance and common schema are effective, but the latter is usually at the application level (i.e., defining databases). The next step is to create data catalogues that include data lineage. She noted that many people have not adopted common schema because they want to move quickly, which is not possible at the enterprise level. Lt. Gen. Hamel asked how these processes became self-reinforcing in the healthcare industry. Dr. Chute explained that before regulatory mandates were implemented, “carrots and sticks” (i.e., rewards and penalties) were used to incentivize conformance to ONC standards. He envisioned that Air Force contractors could have their devices and resources generate and transmit metadata in a way that is conformant and relevant to the Air Force’s needs for near-real-time situational awareness. He acknowledged that providing this level of electronic accessibility to enable inference could create serious new security vulnerabilities. Lt. Gen. Hamel observed that the mandates for protection of private health records have led to significant security measures. Dr. Chute commented that encryption and multiple-authentication for access are standard practices; cybersecurity is foremost in the mind of the chief information officer of any healthcare organization, which was not the case 25 years ago. He described this as a “co-existing cultural evolution” of the importance of security and the availability of the data. An unanticipated benefit is that the research community’s ability to draw inferences about the healthcare system has advanced, owing to the availability and integration of these data sets across organizations. Dr. Drew clarified that having a common data schema does not necessarily mean that only one system exists or that everything will be protected in the same way. Data can be segmented and prioritized, and the security posture can be tailored to priorities and risk management.

Lt. Gen. Hamel wondered which users should be involved in creating data definitions and whether they need to map to communities of practice across the enterprise. Dr. Chute replied that this should be a team effort. Because “the experts” may not know how to communicate content, both domain experts and knowledge engineers are integral. He noted that unless senior leaders are trained to think in information-enabling terms, the potential and the opportunities of data for decision making might not be obvious. Once these opportunities are presented, the benefits are clear. He asserted that with top-level leadership understanding that knowledge and data are primary assets that could be coordinated, the organization could become more successful and efficient.

Dr. Langston asked about the role of blockchain systems in supporting the movement of healthcare data. Dr. Chute responded that blockchain is computationally intense and might not be practical for medical data; but that may not be the case for military data. Lt. Gen. Ted Bowlds (USAF, ret.), chief executive officer, IAI North America, asked about authoritative data sources. Dr. Chute noted that healthcare tends to be a more federated environment, and the ONC is responsible for standards and specifications. Patient management is a localized decision, he continued, which is very different from the centralized approach of the military. Mr. Alden Munson, senior fellow and member, Board of Regents, Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, added that there is a basis to allow consolidation of data from various sources for a position report, for example, even though some are of much higher quality than others. Lt. Gen. Bowlds underscored that there has to be a way to identify ground truth when data are coming from multiple locations or sources.

Mr. Munson pointed out that if the Air Force achieves its vision, it will become a more attractive cyber target—a security construct that is included in the architecture at a fundamental level and is matched to that challenge is needed. While he expressed his support for use cases, he emphasized the need for an underlying holistic architecture process, because the pilot programs have to be compatible with the evolving architectural vision.

OUT-OF-THE-BOX LEARNING: PANEL TWO

Mr. Chris Lynch, chief executive officer, Rebellion Defense, and former head of Defense Digital Services (DDS), observed a need to reshape the overall focus for defense and national security, including

reconsideration of who serves as trusted advisors, builders, and creators. He described the cautionary tale of Healthcare.gov, which cost $1 billion yet only allowed six people to create accounts on its launch day. He expressed his frustration with the government spending so much on something that initially garnered so little value—a direct contrast to the progress in the software industry.

When the White House created the U.S. Digital Service, Mr. Lynch worked on medical record transfers from DoD to the Department of Veterans Affairs to ensure the best care for veterans. A simple file format conversion problem could result in the death of a veteran, a problem that was solved in 1 week by his team of software engineers who created file format converters. Motivated by this experience, he launched DDS, which recruited software engineering experts to address problems for which technology was failing a mission. This team worked on a ground-control system for the global positioning system; although hundreds of millions of dollars had been spent on this system, it was operating at a level comparable to that of 20 years prior. Because the ground-control system had 21 components, it took 3 months to test it. To address this problem, the team used DevOps to automate the process, reducing the testing time to less than 1 hour. The team addressed similar issues with the Joint Strike Fighter and its flight control system. During both projects, the team worked to secure the military’s software (e.g., through challenge programs such as “Hack the Pentagon”) using approaches that were standard in commercial software companies.

Mr. Lynch aimed to convince DoD senior leadership of the value of hiring technical people (with recent and relevant experience) in positions of authority to make decisions on technical problems. He emphasized that the world is entering an era with nearly unlimited compute and unlimited storage; software is going to transform the defense mission by creating competitive advantage as the industrial manufacturing era ends and the software superiority era emerges. The military currently solves problems with human capital; however, he asserted that because the scale of the global threat environment and the great power competition is too great for human beings, it is critical to leverage new technology to enable software superiority. Modern software will allow the military to see, decide, and act first at a scale greater than that of any one individual.

He explained that Rebellion Defense was created ~2 years ago with a vision for software superiority and a goal to enable better and faster decision making in a world in which the platforms, domains, Combatant Commands, and services have all been connected or collapsed. Rebellion Defense relies on unlimited compute and storage and uses artificial intelligence (AI) and data to lead to decision advantage (i.e., machines and humans each work to their respective strengths) in the era of great power competition. He shared several lessons learned from his experience in the commercial sector:

- Awareness that different types of technology companies have different roles and attract different types of talent. Hardware and industrial manufacturing companies build things, such as jets; services companies have conversations with the customer about what to build and follow through on making sure that it is built; and software companies build products.

- Value of a connected ecosystem. DoD would benefit from thinking about connections in terms of application programming interfaces (APIs), which make it possible to “rip and replace” other products when capabilities are introduced that better meet customer needs.

- Need for continuous deployment of new models. Most of the advantages of AI and machine learning (ML), computer vision, and joint all-domain command and control (JADC2) will only be realized by embracing the ability to continuously deploy new capabilities quickly and cheaply into the warfighting environments.

- Value of leveraging the right resources. Defense is a world-scale business that requires resources that far exceed the DoD research and development budget. It will not be possible to attract commercial software companies into defense if DoD infrastructure and technology is orthogonal to what they are already building—they have used commercial cloud for more than 20 years at scale, have billions of users, and process data at volumes that far exceed most missions within DoD.

In closing, Mr. Lynch advocated for creating disruption among processes that are fundamentally broken and doing them better, faster, cheaper, with more trust, and at scale. Despite the fact that DoD partners with many top tier universities, graduates choose jobs in other sectors because they fear that the government bureaucracy is untenable. He said that the government has to present opportunities to do incredible, forward-leaning work in support of the nation in order to hire the right people.

Col. David (Matthew) Neuenswander (USAF, ret.), Chief of Joint Integration, The Curtis E. LeMay Center for Doctrine Development and Education, explained that the Defense Information Systems Agency is responsible for U.S. Message Text Format (USMTF). Approximately 330 USMTF messages define air space coordination measures, fire support coordination measures, and defense coordination measures, and they identify the areas where business is conducted as machines communicate and attempt to exchange messages. The Theater Battle Management Core System (TBMCS), the Air Force’s largest command and control system, wrote the air tasking order, air space control order, and air space control plan, and communicated with all of the other joint systems (e.g., the Army Tactical Air Integration System and the Air Defense System Integrator) using USMTF. In 2004, he continued, the Air Force replaced TBMCS with another system that ultimately did not work. In the interim, the funding stream for USMTF that was in TBMCS at the 2004 level was frozen. Since that time, the doctrine community created new doctrine and put it in USMTF; while the doctrine version is up to 2020 and there have been substantial changes to USMTF, none of those changes are in the machines. So, an important question emerged: Is the doctrine what is in the machines, or is doctrine what is written on paper?

Col. Neuenswander provided an example of a significant airgap that was recently revealed. The 2004 version of USMTF uses “restricted operation zone” (“ROZ”). However, “ROZ” is not in the 2004 version of TBMCS; only “ROA” (for “restricted operation area”) is included. Thus, while ROA is found in TBMCS, only ROZ appears in the doctrine. Although a human could understand and navigate this mismatch in terms, a machine could not. He noted that first step to address this problem was to determine what command and control systems exist and what version of USMTF each is using. It became apparent that some of the air operations centers are still using the 2000 version because some of the allies did not want to update their machines to the 2004 version. The use of different languages to communicate with machines across the world creates significant issues for JADC2. He asserted that everyone should adopt the same format, but that requires first determining what formats are still in use. He anticipated that funding will be restored so that TBMCS can be updated.

Dr. Drew asked how likely it is that everyone would conform to the same format and, if not, how to solve the problem. Col. Neuenswander pointed out that there is already a standard directed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, although not everyone is part of it. He added that in 2019, doctrine was demoted to “advice,” which could be one of the reasons people use different systems. However, he underscored that if people want machines to take over certain tasks, it is imperative that everyone use the same language format. He hypothesized that the Chinese likely all use the same system and emphasized that this is a real problem for the United States; someone needs to take ownership and provide authoritative direction because it is crucial to update so as to have the capacity for all systems to communicate.

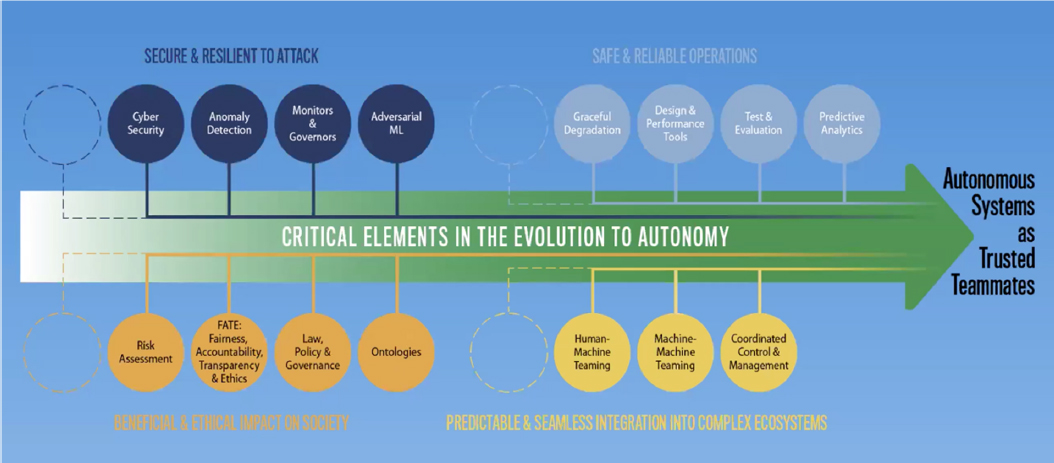

Dr. Cara LaPointe, co-director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Assured Autonomy, described the role of autonomous systems in digital transformation. Echoing Mr. Lynch’s perspective, Dr. LaPointe said that the national security enterprise is entering a software era, and autonomy and AI will be key to success. She emphasized that a level of trust has to be developed, as people who do not trust autonomy will not use it. The first step is to understand the ways in which AI and autonomy could transform an organization’s ability to accomplish its missions by identifying the problems that need to be solved and how to approach solving them differently by leveraging these technologies.

She defined autonomy as anything AI-enabled that begins to interact without human intervention (e.g., cyber physical systems, decision algorithms). Autonomy is increasingly entering every realm of society. The first wave of AI included handcrafted knowledge and human-built models based on expert systems. In the past two decades, the technology progressed to machine learning, and now the focus is on contextual reasoning. Getting autonomous and AI-enabled systems to work safely, securely, and robustly is challenging, especially given that these technologies are expected to integrate into an entire ecosystem. She

stressed that policy and other governance mechanisms are equally important, as is understanding the complex strategic feedback loops among all of these areas.

Dr. LaPointe highlighted several questions related to the unsolved challenges of autonomous systems:

- How do we ensure that autonomous systems will operate safely in an unconstrained world? How do we do more test and evaluation?

- How do we create better design tools to build more reliable autonomous systems?

- Do all autonomous systems need to be explainable?

- If accidents happen, how do we know what went wrong, and how are these systems auditable?

- How do we prevent systems from learning bad behaviors in data sets?

- How do we manage autonomous systems in a crowded dynamic ecosystem, especially in environments where people and autonomous systems are operating side-by-side?

- How do we monitor autonomous systems to ensure that they are operating as intended, while recognizing that it is impossible to eliminate all risk?

- How do we proactively create effective policy? It is important to understand both the policies for the actual use of the systems and the policies involved in the creation ecosystem in order to realize the full benefits of autonomy and provide “guardrails” against potential negative impacts of the technology.

- How could the technologies be attacked (e.g., via manipulating inputs to algorithms)?

She emphasized that building a holistic framework of assured autonomy is critical to achieving safe and reliable operations that are (1) secure and resilient to attack, (2) predictively and seamlessly integrated into complex human ecosystems, and (3) beneficial (e.g., saving money and time) and ethical. She said that many tools need to be created to fully realize the benefits of autonomy (see Figure 4.3), and challenges remain to collect and fuse underlying data.

In closing, Dr. LaPointe shared several lessons learned and success strategies. Most importantly, digital transformation is a human challenge that will not be solved in isolation by technologists. Robust communication, cooperation, and feedback mechanisms are needed across organizational siloes (i.e., operators, users, and technologists). Contractors also have to be brought into the conversation to enable streamlined acquisition. Change is difficult, and cultural impediments are real, she continued. In DoD, the main challenge is that often no one “owns” the whole transformation process. Leaders who understand both the mission and the technology are critical, as is a human-centered approach that is inclusive of all stakeholders. She asserted that change management is essential to overcome cultural impediments. Technology is rarely the barrier in moving from proof-of-concept to solutions at scale—it is the enablers, assurance, and transformation of the entire “DOTMLPF-P” (doctrine, organization, training, materiel, leadership, personnel, facilities, and policy) ecosystem. She emphasized that government acquisition processes underestimate the sustainment needs of digital technologies and suggested adequate resourcing for digital sustainment and preparation to make trade-offs among priorities.

Dr. Langston asked if explainable AI can be used to mitigate any of the aforementioned challenges. Dr. LaPointe replied that the ultimate goal is to make the technology trustworthy and trusted; explainable AI is one approach, but it is not sufficient on its own.

Mr. Randall Hunt, director of developer relations, Vendia, described an evolution in business logic over the past 15 to 20 years from monolith, to microservices, to functions-as-a- service and ephemeral compute. A monolithic application is essentially one large code base that is expensive, and difficult to create and run. These applications are powered by monolithic databases that have complex entity relationship diagrams, which become even more complex when trying to add and share data with partners, vendors, customers, or users. He explained that managing these relationships is a full-time job, and the entity relationship models become tribal knowledge—understanding and contributing to these models requires a significant investment of time. Although schema-less data stores have made improvements, they have not solved this problem.

Approximately 20 years ago, Mr. Hunt continued, monoliths began to split into service-oriented architectures. For example, rather than residing within the existing monolithic layer, an authentication layer would live on its own server and communication would occur over XML and other early protocols that were parseable by machines. This allowed for individual services to be scaled and then abstracted, and it improved the pace of iteration for individual teams. Approximately 10 years ago, microservices became the primary method by which teams were building applications.

Mr. Hunt noted that because the same code was being written 100 times to do functionally the same thing, the focus shifted from the servers to the business-based, product-based logic between all of the foundational bricks. And because most were not running continuously, it was possible to invoke functions, leading to the use of functions-as-a-service. Functions-as-a-service models power telephone tree systems and text messaging, for example.

He defined DoD as a unique “business” that has a global platform and a substantial amount of work proceeding in thousands of different directions. As networking and compute continue to improve over time, DoD will need an infrastructure that leverages those improvements as soon as they happen. This core infrastructure, however, is already built—it exists in the commercial, private, and secured government sectors. He emphasized that there is no reason for DoD to reiterate or expand that infrastructure, because vendors continue to innovate and improve regardless of defense investment. Software is becoming the “differentiating factor” because it has the ability to make strides well beyond the fixed advances of hardware (e.g., changing one line of code can increase performance by 100,000) for minimal investment. He suggested that organizations like DoD focus on the logic and the software of their product instead of the logic and the operational infrastructure of their compute backends. People often dedicate too much time to building large operations teams; managing cloud resources; sharing; continuous integration/continuous delivery; and authorizing, complying, and auditing but not enough time on the data model—understanding the data model and how to create something from it drives improvement. With its focus on business logic, Vendia provides a GraphQL API when customers submit a data model, which allows customers to iterate quickly. In closing, Mr. Hunt underscored that any organization investing in or building a monolith in 2021

is making a mistake. The next generation of businesses will be those who take advantage of their data quickly and effectively to make decisions, move forward, and iterate.

Dr. Drew championed Mr. Hunt’s advice to DoD to avoid investing time, energy, and resources in the creation of infrastructure that is already available, because doing so does not add value to the business or the mission. Dr. Langston asked about the differences between developing functions-as-a-service and developing microservices and containers. Mr. Hunt explained that each functions-as-a-service platform has advantages and disadvantages, but the primary benefit is that a single developer can focus on a single function and reason over a set of functions. To take advantage of functions-as-a-service, he continued, one should separate the area of interest and the data layer. When building with containers, there is concern about compute and memory usage given the individual number of containers that are deployed on a server; with functions-as-a-service, the only concern is roundtrip network latency. A case in which a container would be a better choice than functions, however, would be a live speech transcription. Dr. Drew inquired about the largest enterprise that has used functions-as-a-service as a substrate for its product development and whether this approach is being used in DoD. Mr. Hunt replied that a substantial portion of Amazon runs on functions-as-a-service, as does the Financial Regulatory Authority, for example. Several large organizations have built entire platforms on top of functions-as-a-service, and their business models have pivoted: they have become more resource effective and can iterate more quickly on smaller pieces of the application. There are a few functions-as-a-service deployments in the government sector more broadly. In response to a participant’s question about blockchain, Mr. Hunt noted that much of the public chain is slow. He advised against DoD’s investing significantly in any public chain, because it is unlikely to solve the specific problems in need of solutions. However, the concept of a ledger data store could be powerful.

WORKSHOP TWO CLOSING REMARKS

Gen. Holmes referenced an article1 that considers the U.S. military’s intent to connect every sensor and shooter to be the wrong approach. Because China dedicates resources to counter each U.S. effort (e.g., communications paths, electronic warfare systems), it is important for the Air Force to build systems that are resilient to attack as well as to be prepared to continue the fight when those systems fail.

In light of the Air Force’s plans for digital transformation, Col. Scott McKeever, director, Chief of Staff of the Air Force Strategic Studies Group (SSG), mentioned a case study2 about the challenges of the recent evacuation operations in Afghanistan. He said that the Air Force is a global organization with many components and many chiefs—achieving unity of effort is essential but is proving difficult. He noted that the first two workshops in the series have provided several useful paths forward for the Air Force—for example, via investments in people, processes, and technologies at scale.

Col. Douglas DeMaio, 187th Fighter Wing Commander, Alabama Air National Guard, provided an overview of the planned agenda for the final workshop of the series, and Lt. Gen. Hamel invited planning committee members and workshop participants to share their observations from the first two workshops of the series. Dr. Green said that with the exception of a few small integration case studies, too many stovepipes remain in the Air Force: the large-scale integration needed to move from data to decisions is missing. She noted that Mr. Caron’s model of zero trust is a good first step, but it only addresses the security aspect of data (i.e., how to protect them), not necessarily the distribution aspect of data. She also observed that although presenters discussed “structure” and “taxonomy,” there was no discussion of “knowledge.” She explained that algorithms have to reference knowledge, which is actionable for decision making. She emphasized that AI and knowledge go hand in hand: intelligence creates information, and information

___________________

1 C. Dougherty, 2021, “Confronting Chaos: A New Concept for Information Advantage,” War on the Rocks, https://warontherocks.com/2021/09/confronting-chaos-a-new-concept-for-information-advantage/.

2 A. Eversden, 2021, “Lack of Access to Data During Afghanistan Exit Shines Light on Tech Gap,” C4ISRNet, https://www.c4isrnet.com/battlefield-tech/it-networks/2021/09/08/lack-of-access-to-data-during-afghanistan-exitshines-light-on-tech-gap/.

creates data. In addition to these data challenges, Lt. Gen. Hamel noted that figuring out how best to use available technology and create the organizational constructs and governance to do so remains difficult. Dr. Green described this as an issue of the connection between the vision and the mission: the Department of the Air Force (DAF) has to determine what it wants to achieve and improve before creating a strategy.

Dr. Ryan shared her observations from the first two workshops in the series. She echoed Robert Tross’s suggestion that the Air Force focus on the how rather than the what for digital transformation. The discussion about the value of managing change, monitoring progress, and reimagining processes instead of digitizing existing processes resonated: because data have become a major weapon system and the DAF plans to exploit data to an unprecedented degree, the DAF has to be prepared for those data to become a major target for the adversaries. Therefore, she continued, the Air Force has to translate its strategic needs for future competition and conflict into improvements to the data superstructure, without being overwhelmed by current acquisition processes but also by developing new system requirements and decision-making policies and processes. The barrier to achieving this vision is thinking about digitization in terms of only the data objects instead of the entire digital ecosystem. In a digital ecosystem, everything but the hardware is data. She cautioned that total digitization is not a simple process: a series of decisions has to be made about the target data format; sampling rates; storage strategy; and transition plan, which prioritizes goals, considers how data storage obsolesces, and maps how to migrate data from old to new platforms. She emphasized that it is critical for the Air Force to have a strategy for creating and maintaining minimum essential data sets that are immediately available for continuity of operations when data repositories, including cloud enclaves, are attacked physically or virtually. She explained that decision pathways (and their roadblocks) need to be considered as part of the overall digitization strategy. Human knowledge about how to use data appropriately is important, especially when operating in a degraded data environment—quality training and education thus become a higher priority than certification. Last, she remarked that the strategic use of data (particularly the logistics of data) needs to be studied specifically from a warfighting perspective. Dr. Green noted that all of these activities require the right people who understand strategic warfare and can develop the architecture. While operations are ongoing, the Air Force has to take a step back for planning.

Dr. Langston observed that not enough energy, time, or resources are being spent on data: data sharing has been a long-standing problem within DoD, one that has become worse as cybersecurity issues have increased. The DoD Instruction Series 8350 states that everyone must share their data, but people are not penalized for failing to do so—that has to change, he asserted. For example, Virtual Alabama ceased funding for people who did not add their data to the Google Earth Layer. Lt. Gen. Hamel asked whether the military’s existing systems make it difficult to share data or if people are simply unwilling to do so. Dr. Langston suggested that the problem is multi-layered. Those in charge of funding will lose the money if it is not spent properly and quickly; if there is no “requirement” to share data, people may not want to focus what little money they have on that activity.

Dr. Paul Nielsen (USAF, ret.), director and chief executive officer, Software Engineering Institute, Carnegie Mellon University, remarked that with so much data flowing in and out of the system, sometimes decision making occurs at a high level where people are not in immediate contact with the problem and thus do not have the right context to make a decision. He supported Mr. Lynch’s assertion that technical decisions need to be made by technically competent people. Dr. Langston noted that although some of the current senior leadership understand the need to reduce time cycles and become more efficient, an overabundance of Pentagon oversight remains a barrier to progress. Dr. Nielsen added that the Director of Defense Research and Engineering for Research and Technology staff grew substantially from 2000 to 2010, and Lt. Gen. Bowlds said that these additional staff are essentially generating work that does not need to be done. Lt. Gen. Hamel advocated for the active use of new tools and authorities, the empowerment of lower-level decision makers, and action on smaller and shorter time scales to better meet user needs—large programs of record often collapse under their own weight.

Lt. Gen. Hamel commented that because digital transformation affects every member of the organization, it is important to identify communities of practitioners and their responsibilities across the enterprise. He advised against using the Advanced Battle Management System (ABMS) as the “flagship of

transformation.” Dr. Langston said that in the Navy, progress is slowed by the requirement for program managers to report to the contracts and legal departments. Lt. Gen. Bowlds noted that the Air Force has made the same mistake by giving more power to the contracting officers than to the program managers. Dr. Langston suggested the adoption of something similar to Platform One across all of the services, and using it iteratively to build software programs. However, he cautioned against having all of its components maintained by the Air Force instead of by commercial providers.

Gen. Holmes perceived that the absence of Air Force Systems Command is palpable: under that system, it was possible to identify a threat, create a concept of operations, and acquire the needed platforms or networks. By connecting acquisition and sustainment, a focus on the acquisition process was lost: the Air Force Materiel Commander was removed from the loop, and the program executive officers (PEOs) worked directly for the senior acquisition authority without any real link to the operators, warfighters, or the threat. This model has essentially turned PEOs into contracting officers. Significant staff cuts in the Air Force have also reduced its capacity to think through a problem and deliver and execute a solution (e.g., the Air Force Materiel Command has lost 5,000 acquisition PEOs who are needed to manage existing programs). He noted that the Air Force has aging, ineffective, and expensive systems that have to be replaced because China and Russia have had 40 years to learn how to defeat these systems. Digital modernization provides the opportunity to leapfrog Russia and China and negate their investments. He advised against purchasing “next-gen” systems; they are too expensive and often function in the same way as the old platform. He emphasized that although there are many people in the Air Force who are interested in transformation and are trying to move forward, the coordination and cooperation needed to create a unity of effort are missing. The lessons learned from other large organizations and the commercial sector become meaningless if the Air Force does not develop this unity of effort. To leapfrog Russia and China, the Air Force has to lead a change management effort, which includes incentives, that allows for the acquisition of new capabilities in a reasonable time frame. He shared a motto from a former maintenance group commander that is still relevant today: “the purpose of analysis is insight, and the purpose of insight is to drive decisions. And anything that does not lead to insights to help with decision making is wasted time.”

Dr. Rama Chellappa, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of electrical and computer engineering and biomedical engineering, Johns Hopkins University, observed that in the case study on medical records, the strategy was driven by a clear goal (e.g., diagnose a disease, monitor patient improvement). Before it can consider how to do digital transformation, the Air Force needs to specify its goals. Dr. Green suggested that the goals be broken down into objectives that are aligned with functions. Instead of having technology drive the process, she continued, the emphasis should be why and how technology will be inserted into a current function to improve performance. Lt. Gen. Hamel added that it is critical to define problems so that they can be logically decomposed and reintegrated as solutions are identified.

Lt. Gen. Bowlds shared several themes that he noticed over the course of the first two workshops: (1) Senior leadership has to drive the culture change needed for digital transformation, and the strategy has to be consistent as these leaders change. Trust has to be decentralized—more data are exposed and people are given more tools, and the decisions are driven further down into the organization. (2) Stovepipes have to be removed to enable true integration. (3) A plan is needed to remove critical legacy systems without interrupting operations. (4) Digital transformation is about data. When acquisition programs generate their own data rather than sharing data, duplication emerges. It is important to instead identify authoritative sources and focus on data integrity. He emphasized that ABMS and JADC2 are not “strategies” to enable data sharing; an operational concept is needed.

Mr. Munson commented that when there is a difficult problem to solve, it is important to consider why the solution is elusive. He defined acquisition in two ways: “acquisition” includes the contracting programs and the budgeting staff from the agency, while “Acquisition” includes those with oversight in the Pentagon; the administration; and congressional committees, authorizers, and appropriators. He suggested that the Air Force create a team focused on “Acquisition” to increase program effectiveness. He also proposed that the Air Force pursue industrial-strength security for its enterprise; if it achieves a true digital transformation, it will become an even larger target for adversaries. Although many pilots and prototypes have been successful, Mr. Munson described them as “the enemy of the enterprise-level effort” because it is unlikely

that any of these prototypes can serve as the foundation on which to build the needed architecture. Although prototypes provide a learning opportunity, the resources needed to fund prototypes detract resources from larger initiatives. He encouraged domains across the service to define their use cases: What result do they desire? What data do they need? What communications and connectivity do they need? He advocated for the creation of a “recipe” to define use cases, complete dozens of them, and learn how their integration could characterize the architecture that is derived from core mission needs. Last, he posited that the intersection of Air Force and Space Force needs does not extend beyond human resources functions and suggested a distinct separation between the ways in which the Air Force and Space Force think about their respective missions. Lt. Gen. Hamel recognized that the Air Force and Space Force have different missions, but he reiterated Gen. David Thompson’s assertion that because the Space Force is small (in size and in funding), it is dependent on the Air Force beyond personnel. The common digital infrastructure has to come from the Air Force because it is funded at a higher level. He added that when done well, use cases are an effective mechanism to extend an abstract concept of operations. He suggested broadening the notion of “community of practitioners” across the whole of the services before identifying important use cases. Gen. Holmes said that policy, resource, and funding gaps prevent people from executing a strategy, which could be achieved if someone would take charge and issue the request.

Mr. Edward Drolet, deputy director, Chief of Staff of the Air Force SSG, suggested that the planning committee contact Maj. Gen. Michael Schmidt for his perspective on digital transformation. Mr. Drolet noted that an innovation ecosystem is being developed for the Air Force, as it works diligently to move programs to minimum viable products, demonstrate capabilities, and balance cost and scale. Gen. Holmes said that vice chiefs and chiefs sometimes create entities similar to the SSG when their own staff are underperforming. This approach often leads to resentment, in which case it could be difficult to achieve buy-in among those staff. These entities may represent an organization that is not functioning appropriately as opposed to an organization that is transforming. Mr. Drolet assured Gen. Holmes that the SSG is tracking several initiatives that provide overall direction and monitor digital issues for the transformation (see Appendix D).

Dr. Nielsen observed that companies that have had successful digital transformations, such as Walmart and Amazon, are DoD-size organizations. However, with the added challenge of legacy systems and processes, it will be difficult for the Air Force to transform—but doing so is essential to remain relevant in the future. He stressed that if the Air Force does not use modern software engineering techniques and modern systems engineering and architecture, the uniformed, civil service, and defense industrial staff will seek jobs elsewhere to do more innovative work.

Dr. Drew categorized the discussion from the first two workshops in the series into five themes: (1) Outcomes, decisions, and goals can be realized when there is a specified problem to solve, which is not currently the case for the Air Force. The Air Force could focus its work in areas of mission operation, acquisition/development, maintenance, and business support/administration. (2) Leadership and governance, as well as funding, are key aspects of the digital transformation. She suggested the creation of a “digital board” to carry out the governance of projects (versus retaining siloes). (3) A variety of approaches toward (e.g., starting with an enterprise view, seeking quick wins) and methodologies for (e.g., agility, failing fast, experimentation, change management) transformation exist. Focusing on data and mission logic instead of the backend infrastructure is critical, she continued, as are considerations for cybersecurity, zero trust, data governance, and cross-functional teams. (4) Several challenges remain for the Air Force, the first of which is that ownership of processes that span multiple groups needs to be determined. Other potential barriers include creating buy-in, incentivizing people to share their data, and balancing centralized and decentralized control. (5) Many case studies exist to demonstrate the “what” and the “how” of successful transformations.