1

Information Technology, Productivity, and Creativity

The benefits of information technology (IT) extend far beyond productivity as it is usually understood and measured. Not only can the application of IT provide better ratios of value created to effort expended in established processes for producing goods and delivering services, but it can also reframe and redirect the expenditure of human effort, generating unanticipated payoffs of exceptionally high value. Information technology can support inventive and creative practices in the arts, design, science, engineering, education, and business, and it can enable entirely new types of creative production. The scope of IT-enabled creative practices is suggested (but by no means exhausted) by a host of coinages that have recently entered common language—computer graphics, computer-aided design, computer music, computer games, digital photography, digital video, digital media, new media, hypertext, virtual environments, interaction design, and electronic publishing, to name just a few.

The benefits of such practices have economic, social, political, and cultural components. IT-enabled creative practices have the potential to extend benefits broadly, not only to economic and cultural elites (where they are most immediately obvious), but also to the disadvantaged, and not only to the developed world but also to developing countries. And their impacts extend in two directions: Just as the engagement of IT helps shape the development of inventive and creative practices, so also can inventive and creative practices positively influence the development of IT. See Box 1.1. This report explores the complex, evolving intersections of IT with some important domains of creative practice—particularly in the arts and design—and recommends strategies for most effectively achieving the benefits of those intersections.

|

BOX 1.1 The Utility of Information Technology A common answer to the question, What good is information technology?, is that it enhances productivity. Unquestionably, information technology (IT) now helps one to perform many routine tasks with greater speed and accuracy, with fewer errors, and at lower cost. So computers and software products are marketed as productivity tools, investments in IT are justified in terms of productivity gains, and economists try (sometimes without success) to measure those gains. In this role, IT is a servant. An additional claim, which can be justified in certain contexts, is that IT enhances the quality of results. Laser-printed documents not only are quicker and cheaper to produce than handwritten or typewritten ones but may also be crisper and more legible. The outputs of detailed computer simulations of systems may be more reliable, and more useful to engineers, than the approximate, rule-of-thumb hand calculations that were used in earlier eras. And a sophisticated optimization program may produce a better solution to an allocation problem than manual trial and error. In this role, IT supports creative craftsmanship. A still stronger, but frequently defensible, claim is that IT enables innovation—the production of outcomes that would otherwise simply not be possible. Scientists may use computers to analyze vast quantities of data and thereby derive new knowledge that would not be accessible by other means. Architects may use curved-surface modeling and computer-aided design/manufacturing systems to design and build forms that would have been infeasible—and probably would not even have been imagined—in earlier times. And new, electronic musical instruments, which make use of advanced sensor and signal-processing technology, may open up domains of composition and performance that could not be explored using traditional instruments. In this role, IT becomes a partner in processes of innovation. Perhaps the strongest claim is that IT can foster practices that are creative in the most rigorous sense— scholarly, scientific, technological, design, and artistic practices that produce valuable results in ways that might be explained in retrospect but could not have been predicted. At this point, one might detect a whiff of paradox—a variant on Plato’s famous Meno paradox. Unless it offers users a means to produce something they already know they want, IT is not helpful. But if someone produces something merely by running a program, the production process is predetermined and potentially standardized, so how can the result be truly creative? |

INVENTIVE AND CREATIVE PRACTICES

Creativity is a bit like pornography; it is hard to define, but we think we know it when we see it.1 The complexities and subtleties of precise definition should not detain us here, but it is worth making a few crucial distinctions.

Certainly, creative intellectual production can be distinguished from the performance of routine (though perhaps highly skilled) intel-

lectual tasks, such as editing manuscripts for spelling and grammar, or applying known techniques for deriving solutions to given mathematical problems. Less obviously, creativity can be distinguished from innovation; there are plenty of software products and business plans that are (or were) innovative, in the sense of accomplishing something that had not been attempted before, without being particularly creative. And there are many original scientific ideas that turn out to be wrong. There is always something unexpected, compelling, and even disturbing about genuinely creative production.2 It claims value, and it has an edge. It challenges our assumptions, forces us to frame issues in fresh ways, allows us to see new intellectual and cultural possibilities, and (according to Kant, at least) establishes standards by which future work will be judged.3

The implicit and explicit ambitions reflected in creative production tend to differentiate it from routine production. It often focuses on unexpected questions rather than those that have already entered the intellectual mainstream. It goes for high payoffs and is undeterred by accompanying high risks. It seeks out big questions rather than opportunities to make incremental advances, and it looks for fundamental change. It is not bothered by rule breaking, boundary crossing, and troublemaking. And it is characteristically reflexive—engaged in reflecting upon and rethinking processes, not just applying them.

Creative production is not always positive and widely valued; one can be creatively evil, and one can waste creative talents on crazy projects that nobody cares about. But the products of creative science, scholarship, engineering, art, and design—even creative basketball— can bring immense benefits to society, as well as providing deep satisfaction to their originators. So respect is accorded to creative individuals and institutions, and society is often willing to invest in projects and programs that plausibly promise (though can never quite guarantee) creative results.

For Plato, and later for the Romantics, creativity was an ineffable attribute of certain mysteriously favored individuals—a gift of the gods. You could cultivate and exercise it if you had it, but there wasn’t much else you could do about it. Today’s consensus (endorsed by this Committee on Information Technology and Creativity) favors the view that creativity can be developed through education and opportunity,

|

2 |

Hausman (“Creativity,” 1998, p. 454) puts the point more technically, as follows: “Not just anything brought into being invites us to call it a creation, however. There is a stronger or radical and normative expectation that what is brought into being regarded as having newness and (at least for the creator) value. The newness of the outcome of such a radical creative act is a characteristic not simply of another instance of a known class—a numerical newness, such as may be attributed to a freshly stamped penny or a blade of grass that has just matured—but an instance of some new kind. It is a thing that is one of its kind that occurs for the first time, and being thus newly intelligible, is valuable.” |

|

3 |

Immanuel Kant, 1781, Critique of Pure Reason. See <http://www.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Philosophy/Kant/cpr>. Note that as this report went to press, all URLS cited were active and accessible. |

There is always something unexpected, compelling, and even disturbing about genuinely creative production.

that it can be an attribute of teams and groups as well as individuals, and that its social, cultural, and technological contexts matter. The committee tends to believe that it is possible to identify and establish the conditions necessary for creativity, and conversely, that we risk stifling creativity if we get those conditions wrong. Renaissance Florence clearly provided the conditions for extraordinary artistic and scientific creativity, but it is easy to name many modern cities (we will avoid getting ourselves into trouble by doing so) that apparently do not.

More precisely, creative practices—practices of inquiry and production that seek more than routine outputs and aim instead for innovative and creative results—can be encouraged and supported in some very concrete and specific ways. Society can try to provide the tools, working environments, educational preparation, intellectual property arrangements, funding, incentives, and other conditions necessary to support creative practices in various fields.

DOMAINS AND BENEFITS OF CREATIVITY

No intellectual domain or economic sector has a monopoly on creativity; it manifests itself (often unpredictably) in multiple fields and contexts. But the manifestations vary in form and character, in associated terminology, and in the types of benefits that result.

In science and mathematics, the most fundamental outcome of creative intellectual effort is important new knowledge. Generally, scientists and mathematicians are clear on the difference between such knowledge and that which results from incremental advances within established intellectual frameworks. Ground-breaking discovery is widely (though not universally) regarded as a product of great value in itself, but it is also valued more pragmatically—as an enabler of technological innovation.

In engineering, and in technology-based industry, creativity yields technological inventions. Such inventions can result in commercially successful products, in improvements to the quality of life (as, for example, when motion picture technology enabled a new form of entertainment, or when an innovative new drug provides a cure for a disease), and in the generation of income streams through intellectual property licensing arrangements. Thus the social and economic benefits are often clearly identifiable and measurable. In recent decades, information technology has been a particular locus of technological invention, the benefits of which need no elaboration here.4

An important manifestation of economic creativity is entrepreneurship—bringing together ideas, talent, and capital in innovative ways to create and make available products and services. Often, in fields such as information technology and biotechnology, close alliances emerge between the institutions of technological innovation (e.g., research universities) and entrepreneurial activity; each one requires and motivates the other. This is particularly evident in fast-moving, high-tech economic clusters, such as the information technology cluster in Silicon Valley or the biotechnology cluster of Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Cultural creativity manifests itself in the production of works of art, design, and scholarship. Like contributions to scientific and mathematical knowledge, such works are highly valued in themselves. Nations and cities take immense pride in their major cultural figures, their cultural institutions, and their cultural heritage. Many value the experience of producing as well as consuming art, design, and scholarship. Not only high cultural practices, such as opera at the Metropolitan in New York City, but also popular practices, such as amateur photography, may be valued for the participant experiences they provide.

Practices of cultural creativity also provide the foundation of the so-called creative industries that seek profits from production, distribution, and licensing.5 One component of the creative industries consists of economic activity directly related to the world of the arts— in particular, the visual arts, the performing arts, literature and publishing, photography, crafts, libraries, museums, galleries, archives, heritage sites, and arts festivals. A second component consists of activity related to electronic and other newer media—notably broadcast, film and television, recorded music, and software and digital media. And a third component consists of design-related activities, such as architecture, interior and landscape design, product design, graphics and communication design, and fashion.

There are some problems with the very idea of “creative” industries. Creativity clearly is not confined to them, and much of what they engage in could hardly be called creative in any sense. Sometimes, as when they devote their efforts to churning out routine “content,” they even seem actively counter-creative. Still, the creative industries do ultimately depend on talented, original artists, designers, and performers to create the value that they add to and deliver, while many artists, designers, and performers depend on the infrastructure of the creative industries and are rewarded by their engagement with the creative industries. The idea is problematic in some respects and there

|

5 |

The U.K. Creative Industries Taskforce, in its 1998 report Creative Industries Mapping Document, defined the creative industries as “those industries which have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent and which have the potential for wealth and job creation through the generation and exploitation of intellectual property.” See <http://www.culture.gov.uk/creative/creative_industries.html>. |

It is possible to identify and establish the conditions necessary for creativity, and conversely, we risk stifling creativity if we get those conditions wrong.

fore should be treated with appropriate critical caution, but it remains a useful one. And, in any case, the name “creative industries” has stuck.

THE CREATIVE INDUSTRIES

That the creative industries are now big business hardly needs emphasis. There have been numerous recent efforts to quantify this intuition by measuring their economic contributions. According to an estimate developed by Singapore’s governmental Workgroup on Creative Industries,6 the United States led the way in the creative industries in 2001, with the creative industries accounting for 7.75 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP), providing 5.9 percent of national employment, and generating $88.97 billion in exports,7 with the United Kingdom, Australia, and Singapore also exhibiting industry sectors of significant size (representing 5.0 percent, 3.3 percent, and 2.8 percent of national GDP, respectively).8

The United States has some important, major creative industry clusters,9 notably those of Los Angeles (with a particular emphasis on film, television, and music), New York (with a particular emphasis on publishing and the visual arts), San Francisco (with particular recent emphasis on digital multimedia), and some smaller, more specialized clusters in cities such as Boston, Austin, and Nashville. In Europe, many creative industry clusters, such as those of London, Paris, and Milan, have developed at long-established centers of culture. In Australia, significant new clusters, based mostly on film, television, and digital multimedia, have emerged in Sydney, Melbourne, and Adelaide. A cluster oriented toward software tools and production has developed in Canada, especially in Toronto and Montréal. The value of such clusters is obvious, so it is not surprising that there has been growing worldwide interest in the regional development strategy of

|

6 |

Workgroup on Creative Industries, 2002, Creative Industries Development Strategy: Propelling Singapore’s Creative Economy, Singapore, September, p. 5. |

|

7 |

For core copyright industries only. |

|

8 |

These numbers represent the percentages of GDP for different years between 1997 and 2001, though the fundamental point remains valid—the creative industries represent a significant segment in each nation’s economy. See Economic Review Committee, Government of Singapore, 2002, “The Rise of the Creative Cluster,” Creative Industries Development Strategy, p. 5. Available online at <http://www.erc.gov.sg/pdf/ERC_SVS_CRE_Chapter1.pdf>. |

|

9 |

Industry clusters are often defined as “concentrations of competing, collaborating and interdependent companies and institutions which are connected by a system of market and non-market links” (see definition of the Department of Trade and Industry, United Kingdom, available online at <http://www.dti.gov.uk/clusters/>). |

encouraging creative industry clusters.10 In the United Kingdom, for example, each of the ten Regional Development Agencies has focused on the creative industries as a growth sector, and each local authority is mandated by the Department of Culture, Media and Sport to produce a development strategy for the creative industries.11

It is important to recognize that these creative clusters do not just consist of large firms. They also encompass independent artists and designers, numerous small businesses, cultural institutions such as galleries and performing arts centers, and educational institutions. Many of those involved with the creative industries may play multiple roles; for example, artists and designers may combine independent practice with teaching, and employees of large firms may “moonlight” with small practices of their own.

But the creative industries also have a strategic importance that extends beyond regional economic development. In a progressively interdependent world where culture tempers and inflames politics as well as markets, strong creative industries are a strategic asset to a nation; the predominance of Hollywood movies, Japanese video games, and Swiss administration of FIFA soccer are forms of soft power that have global, albeit subtle, effects, particularly in countries whose bulging youth populations have access to television and the Internet. Movies, music videos, fashion, and design foster aspirations in the developed and developing world. It matters that teenagers in China—or Pakistan—idolize Michael Jordan. The ability to generate a cultural agenda via the arts, design, or media is a form of deep, pervasive influence and is as integral to global leadership as trade policy or diplomatic relationships.12 Globally available cultural products serve as a kind of common social currency in an increasingly fractured and fractious world. To that extent, the reach and robustness of a nation’s creative practices can constitute a form of global leadership—while also, of course, potentially attracting charges of cultural imperialism. A nation’s creative practices can also provide valuable visibility and branding, as with Italian and Finnish design.

|

10 |

See Chapter 7 for further discussion. |

|

11 |

See Department of Culture, Media and Sport, Creative Industries Program, 2000, Creative Industries: The Regional Dimension, Report of the Regional Issues Working Group, February. Available online at <http://www.culture.gov.uk/creative/index.html>. |

|

12 |

See Shalini Venturelli, 2001, From the Information Economy to the Creative Economy: Moving Culture to the Center of International Public Policy, Center for Arts and Culture, Washington, D.C., available online at <http://www.culturalpolicy.org/pdf/venturelli.pdf>; and Joseph S. Nye, 1999, “The Challenge of Soft Power: The Propounder of This Novel Concept Looks at Lloyd Axworthy’s Diplomacy,” Time, February 22, available online at <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/intl/article/0,9171,1107990222-21163,00.html>. |

Creative clusters encompass independent artists and designers, numerous small businesses, cultural institutions such as galleries and performing arts centers, and educational institutions.

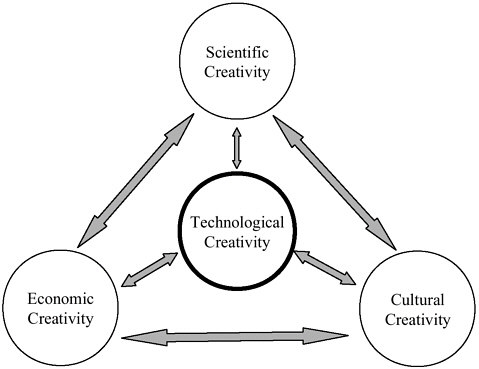

FIGURE 1.1 Domains of creative activity.

INTERACTIONS AMONG DOMAINS OF CREATIVE ACTIVITY

For some purposes it is useful to distinguish scientific, technological, economic, and cultural creativity, as discussed above. But it is also important to emphasize that these domains are often tightly coupled, and that activity in one may depend on parallel activities in others. This committee was charged and constituted to focus primarily on creative practices in the arts and design, and their intersections with information technology, but it recognized that the coupling to other domains of creative practice could not be ignored.

Figure 1.1 illustrates the approximate nature of that coupling— each broad domain of creative practice in two-way interaction with every other. Reflecting a National Academies/Computer Science and Telecommunications Board perspective, technological creativity is shown at the center of the diagram, which of course could also be redrawn to show any of the other domains at the center.

Consider, for example, some important interactions of technological creativity with other domains. Scientific discovery sometimes drives technological invention, but conversely, the pursuit of technological innovation often suggests scientific questions and ideas. Similarly,

entrepreneurial energy may motivate engineering and product innovations, but such innovations may also demand creative strategies for successfully bringing inventions to the market. And newly invented technologies may produce bursts of artistic and design creativity—as with Renaissance perspective, photography, film, radio, television, and computer graphics—while the work of artists and designers may generate desire for technological innovations, shape the directions of technological investigations, and provide critical perspectives.

The additional reciprocal relationships indicated by Figure 1.1 are no less worthy of note. In the creative industries, innovative entrepreneurs develop new ways to produce and distribute creative products, while creative production often demands of businesses and institutions (such as museums, cultural foundations, and art and design schools) new distribution, curatorial, preservation, and other strategies. There is a subtle, complex, but undoubtedly important (in some periods, at least) relationship between the intellectual frontiers of the creative arts and the sciences. And there are even cross-relationships between scientific and economic innovation—as when physics Ph.D.s moved to Wall Street and brought with them new tools and methods for the financial industry.13

Innovative design is often situated precisely at the intersection of technologically and culturally creative practices. On the one hand, designers are frequently avid to exploit technological advances and to explore their human potential. On the other, they typically have close intellectual alliances with visual and other artists. And innovative design can yield high economic payoffs; firms such as Apple, Sony, Audi, and Target have differentiated themselves and in some cases turned themselves around through innovative design. Volkswagen remade its image, and refreshed its reputation for witty innovation, with the revived and redesigned Beetle. Bilbao put itself on the world map by building the highly innovative Bilbao Guggenheim Museum— a work that embodies many technological innovations and at the same time is engaged with the frontiers of the visual arts. South Korea has recently had great success with a national policy of emphasizing quality and innovation in the design of consumer products.

These various interrelationships suggest the importance not only of specialized loci of creativity, such as highly focused research laboratories and individual artist’s studios, but also of creativity clusters— complexes of interconnected activity, encompassing multiple domains, which provide opportunities and incentives for productive cross-fertilization. Thus a laboratory director might seek to establish a creative, cross-disciplinary cluster of individuals and research groups at the scale of a small organization; a research university provost might seek a creative cluster of departments, laboratories, and centers at the scale

|

13 |

See, for example, “Physicists Graduate from Wall Street,” The Industrial Physicist, December 1999, available online at <http://www.aip.org/tip/INPHFA/vol-5/iss-6/p9.pdf>. |

Innovative design is often situated precisely at the intersection of technologically and culturally creative practices.

of a campus; regional planners might try to encourage formation of creative industrial and institutional clusters within their jurisdictions; and national strategists might seek to do so at even larger scales.

The importance of such efforts is increasingly widely recognized, and a related research and policy literature is emerging: Economists explore the proposition that “economic growth springs from better recipes, not just from more cooking”—that is, from the generation and application of innovative and creative ideas;14 planners analyze “creative cities” and “creative regions” that attract and retain talent, and that provide environments in which creative practices flourish;15 the idea of a “creative class” has quickly become popular;16 and the possibility of shifting from “the information economy” to “the creative economy” has become a hot topic among policy makers from Scotland to Hong Kong.17

THE ROLES OF INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

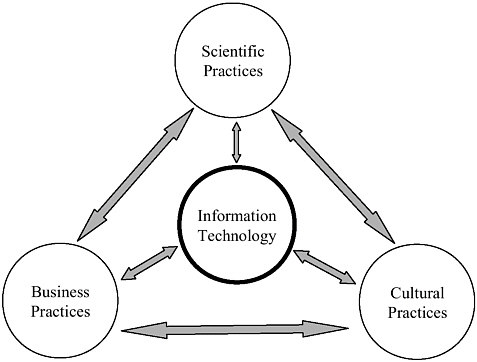

Figure 1.2 shows a more specialized version of Figure 1.1, in which information technology replaces technological creativity at the center. Information technology has important relationships to creative practices in other domains. It benefits enormously from basic scientific and mathematical advances, and in return, it provides scientists and mathematicians with powerful new tools and methods. It provides entrepreneurs with a stream of opportunities to develop and market new products and services, while benefiting from the research and development investment that the prospect of successful commercialization motivates. It provides artists and designers with whole new fields of creative practice, such as computer music and digital imaging, together with tools for pursuing their practices in both new and established fields, while benefiting from the inventive and critical insights that artists and designers can bring to it. Increasingly, the committee suggests, information technology constitutes the glue that holds clusters of creative activity together.

The effectiveness of information technology as glue is enhanced by its extraordinary capacity to apply the same concepts and techniques across many different fields. Once content is reduced to bits, it doesn’t much matter whether it represents text, music, scanned im

FIGURE 1.2 Information technology as glue.

ages, three-dimensional (3D) computer-aided design (CAD) models, video, or scientific data; the same techniques, devices, and channels can be used for storing and transporting it. Once you have a stream of digital data, whatever the source, you can apply the same techniques to process it. Once you have an efficient sorting algorithm, you can use it to order vast files of scientific data or to arrange polygons (digital objects) for hidden-surface removal in rendering a 3D scene. Once you have a library of software objects, you can use those objects as building blocks to quickly construct specialized software tools for use in many different domains.

Furthermore, information technology can support the formation of non-geographic clusters of creative activity. In the past, such clusters depended heavily on geographic proximity for the intense face-to-face interaction and high-volume information transfer that they required. (If you were in the movie business you wanted to be in Hollywood, if you were in publishing you wanted to be in New York, and so on.) Distance is not dead, and these things still matter, but efficient digital telecommunication now supports new types of clusters. Architectural projects, for example, are now routinely carried out by geographically distributed team members who exchange CAD files over the Internet and meet by videoconferencing—with the advantage that specialized talent and expertise can be drawn from a global rather than local pool. Long-distance electronic linkages between local clusters, such as that between the film production cluster in Hollywood and the postproduction cluster in London’s Soho, are also becoming increasingly important.

Many argue that information technology is, by its very nature, a powerful amplifier of creative practices.

And the growing integration of digital storage and processing technology with networking technology and sensor technology is even further strengthening the role of information technology as glue. In many domains, cycles of production, distribution, and consumption can now be end-to-end digital. For example, the production and distribution of a photographic image used to entail a silver-based chemical process for capture, half-toning followed by a mechanical process to print large numbers of copies, and physical transportation to distribute those copies; now, capture can be accomplished by means of a charge-coupled device (CCD) array in a digital camera, replication becomes a matter of applying software to copy a digital file, and distribution through the global digital network can follow instantly.18

Finally, many argue that information technology is, by its very nature, a powerful amplifier of creative practices. Because software can readily be copied and disseminated, and because there can be an unlimited number of simultaneous users, software supports the dissemination, application, and creative recombination of innovations on a massive scale—provided, of course, that intellectual property arrangements do not unduly inhibit creative work. Much of the current debate about intellectual property and information technology focuses on questions of how best to support, encourage, and reward creative practices.19

In summary, information technology now plays a critical role in the formation and ongoing competitiveness of clusters of creative activity—both geographic clusters and more distributed clusters held together by electronic interconnection and interaction. IT is an important driver of the expanding creative industries. And, due to several factors, its role as glue is strengthening. First, the generalizability of digital tools and techniques across multiple domains makes them particularly efficient and effective in this role; they can displace predigital tools and techniques, as in the cases of CAD displacing drawing boards and drafting instruments and digital imaging displacing silver-based photography. Second, the increasingly effective integration of diverse digital technologies is producing efficient, large-scale, multipurpose production and distribution systems that can effectively serve the creative industries. Third, these systems support the formation of non-geographic clusters of creativity that can draw on global talent pools. And finally, the amplification effects that are inherent to information technology are likely to have strong (sometimes unexpected) multiplier effects; they may unleash waves of scientific and mathematical, technological, economic, artistic, and cultural creativity.

|

18 |

CCD arrays consist of tiny light sensors that encode scenes as sets of intensity values. The larger the array, the finer the resolution of the picture. The development of digital cameras has been driven, generation by generation, by the release of successively larger CCD arrays. |

|

19 |

See Chapter 7 for an articulation of the important role played by intellectual property issues in information technology and creative practices. |

THE RACE FOR CREATIVITY IN A NETWORKED WORLD

It seems to this committee that there is an emerging, global race to establish effective, sustainable clusters of IT-enabled creative activity at local, regional, and national scales—and at even larger scales, like that of the European Union. A number of studies and initiatives are directed at this goal, such as the Seoul Digital Media City project (South Korea),20 the BRIDGES International Consortium on Collaboration in Art and Technology (Canada),21 the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (United States), the Kitchen’s national art and technology network (United States),22 and the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (United Kingdom).23 The rewards are high; such clusters are engines of economic growth, of enhanced quality of life, and of cultural and political influence—that is, of soft power. Success in launching and sustaining them depends on capacity to attract and retain creative talent, on establishing the conditions and incentives necessary for that talent to flourish, and— increasingly—on the effective exploitation of information technology.

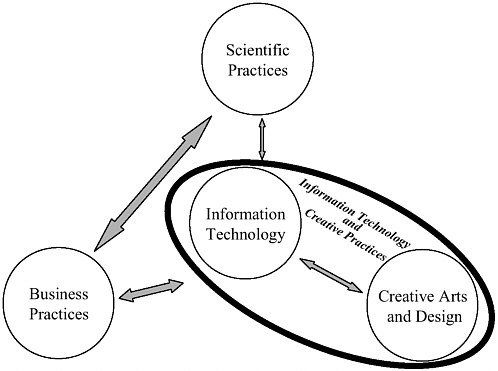

In the following pages, the committee focuses specifically on clusters of creative activity in the arts and design and their interactions with information technology, as illustrated in Figure 1.3—which is simply a subset, but a crucial one, of Figure 1.2. The interactions between these two domains are important not only for their mutually beneficial effects, but also because they help to energize larger systems of interconnected creative activity. This report provides more detailed analyses of the conditions needed for creativity in a networked world and recommends strategies for establishing and sustaining successful clusters of IT-related creative activity in the arts and design. It asks the following questions:

-

How can information technology open up new domains of art and design practice and enable new types of works?

-

How can art and design raise important new questions for information technology and help to push forward research and product development agendas in computer science and information technology?

|

20 |

|

|

21 |

|

|

22 |

See <http://www.thekitchen.org>. |

|

23 |

Additional information about the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art and other initiatives is given in Chapters 7 and 8. |

FIGURE 1.3 Information technology and creative practices.

-

How can successful collaborations of artists, designers, and information technologists be established?

-

How can universities, research laboratories, corporations, museums, arts groups, and other organizations best encourage and support work at the intersections of the arts, design, and information technology?

-

What are the effects on information technology and creative practices work of institutional constraints and incentives, such as intellectual property arrangements, funding policies and strategies, archiving, preservation and access systems, and validation and recognition systems?

ROADMAP FOR THIS REPORT

This chapter provides an introduction to the world of information technology and creative practices (ITCP) and outlines the benefits to the economy and society from encouraging and supporting work in this new domain. Chapter 2 explores the systemic nature of creativity and how multiskilled individuals and collaborative groups pursue work. Various factors, from differences in communication style and vocabulary to evolving work environments, influence how this work is carried out. Information technology is the focus of Chapters 3 and 4.

Chapter 3 analyzes the role of IT in supporting ITCP work and offers observations for the future design of improved IT tools that would provide better support of ITCP. This role for IT—in service to other disciplines—is a well-appreciated one. Chapter 4 challenges this traditional role to consider how the art and design influences of ITCP can help to advance the discipline of computer science. Chapters 5 and 6 discuss the venues for conducting, supporting, and displaying ITCP work. A wide range of venues—from specialized centers for ITCP to museums and corporations—is explored in Chapter 5; ITCP-related programs and curricula in schools, colleges, and universities are covered in Chapter 6. Institutional and policy issues such as intellectual property concerns, digital archiving and preservation, validation and recognition structures, and regional planning are presented in Chapter 7. In Chapter 8, the policies and practices for funding ITCP work are described and analyzed. The discussions from the chapters are synthesized and findings and recommendations are articulated in the report’s opening “Summary and Recommendations” chapter. Although these findings and recommendations are directed to particular decision makers such as university administrators, officers of funding agencies, or directors of cultural institutions, many of the ideas are applicable to multiple decision makers, given that ITCP transcends current institutional, disciplinary, and professional boundaries.