5

Venues for Information Technology and Creative Practices

Individuals and groups involved with information technology and creative practices (ITCP) benefit from participating in venues that support, motivate, and display this type of work. Such venues may occupy physical or virtual spaces, vary widely in scale and scope, range from loosely organized collectives to formal programs, and be either free-standing or connected to established institutions. They can offer important benefits such as access to tools, information resources, work spaces, funding,1 and opportunities for communication among practitioners, those who fund and display ITCP work, and audiences. This chapter describes and analyzes the evolution and characteristics of these venues for the purpose of providing guidance for the design of future ones.

The first section provides a historical perspective on studio-laboratories, which bring together different domains of knowledge, research, and practice—thus combining the artist’s (or designer’s) studio with the scientist’s (or engineer’s) laboratory. This section also introduces the three classes of modern studio-laboratories: multifaceted new-media art and design2 organizations (typically non-profit), mechanisms for public display, and applied research activities in corporations. The remainder of the chapter discusses examples of these types of organizations and activities and draws distinctions between patterns in the United States and those abroad. Programs associated with academic institutions are an important special case and are discussed in Chapter 6.

|

1 |

Funding issues are discussed primarily in Chapter 8. |

|

2 |

New-media art (and design) can be loosely characterized as art (and design) that uses IT in a significant way. Internet art (Net art) is a subset of new-media art, because the Internet is a subset of IT. Digital art is also a subset of new-media art, because new media could incorporate non-digital technologies or content. |

STUDIO-LABORATORIES

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

In the evolution of creative work, the role of individuals in creating new practices and of disciplines in providing tools and methodologies to be reworked is well understood. But the essential role that institutions play in making it possible for individuals and disciplines to come into contact and flourish can be more difficult to recognize. An accurate history of 20th-century developments related to ITCP would counter the widespread but false impression that there has been a renaissance of creativity enabled uniquely by the computer, and would make clear that a gradual development of new institutions, especially the studio-laboratory, has also played a central role.

The term “renaissance,” though, may in fact be appropriate, because the role of institutions in the last century parallels the central, often unrecognized role that they played in the Renaissance. In 1950, art historian Erwin Panofsky pointed out that the age of Leonardo and Durer was one of turbulence, decompartmentalization, and in particular great social mobility after the cloistered separation of the Medieval worlds of theory and practice. The great advances, he added, were indeed made by the instrument makers, artists, and engineers, not the professors. But what made this possible were new institutions, like the academies, that served as “transmission belts” between previously separated domains of knowledge and practice. Perhaps blinded by the brilliance of the rare figure of the da Vincian creator, one may lose sight of the importance of the dilettanti who frequented the academies—people who were “interested in many things.”3 Today’s studio-laboratories are similarly populated.

If the current era is, like Panofsky’s Renaissance, a period of hybridity and interdisciplinarity, then it can also be described as a period where, in many different, local places, experts of diverse kinds, interested in “many things,” meet and learn from one another. The late 20th century has generally been described as a period of postmodernism, in which the stable values of the past were no longer pertinent and were being replaced by a medley of ideas from different sources. Instead of taking the general view that sees ideas as hopelessly jumbled together, one can look for the complex dynamics that arise when specific ideas come into contact with each other at a variety of local, concrete places. This perspective corresponds with recent trends in social theory, in which there is less focus on the individual

|

3 |

Erwin Panofsky, 1952, “Artist, Scientist, Genius. Notes on the Renaissance Dammerung,” The Renaissance: A Symposium, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. |

An accurate history of the 20th century would counter the widespread but false impression that there has been a renaissance of creativity enabled uniquely by the computer.

units of society and more on the complexity that results when they interact with each other. This allows us to move from thinking about art/design and science/technology as two distinct, separate spheres, and to look instead at how they interact with each other.4 From this perspective, the studio-laboratory can be viewed as a hybrid institution where such interaction can occur. A useful demarcation point can be found in the famous Bauhaus slogan “art and technology, a new unity,” in the early 1920s. It is here that a cursory genealogy of the studio-laboratory can begin. See Box 5.1.

THREE CLASSES OF MODERN STUDIO-LABORATORIES

There are three classes (or phases) in the development of modern studio-laboratories: art/design-driven technology development, public diffusion and critical debate, and industrially sponsored applied research. Taken together, the three classes theoretically form a continuum involving upstream experimentation, public diffusion of results, and downstream development. These classes can easily be merged into a single concern for more innovation and creativity in the art-design-technology-science intersection. However, the reality is that the three classes came into being at different times and are rarely in close productive cooperation. Thus, it is not surprising that some aspects of the continuum have been more successful than others, leaving an overall impression of unevenness and some significant gaps.

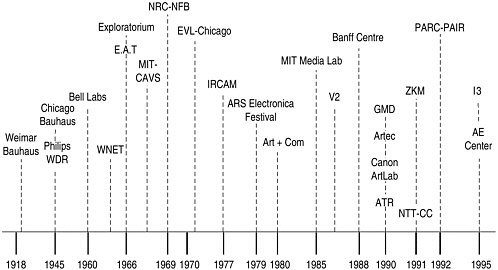

Figure 5.1 conveys in broad outline the increasing frequency with which studio-laboratories were founded, especially after the 1960s. In the first phase, research and production were oriented principally toward the creation of singular, visionary artworks using technology and little concerned with, or constrained by, wider application (or usability) outside the immediate aesthetic context. In the second phase, toward the end of the 1970s, specialized institutions were planned and established to focus on the presentation of new technological art in public arenas, and critical analysis and recognition of such work. The third phase, beginning in the 1980s alongside the opening up of mass markets for personal computers, packaged end-user applications, and cultural commodities like musical instruments and video games, was oriented toward applied research and development.

Among the most oft-cited examples from the first phase was Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), founded by artist Robert

|

BOX 5.1 The Bauhaus Influenced by the 19th-century British arts and crafts movement, the Bauhaus is commonly thought of primarily in terms of the Modern design style with which it is usually associated, or in terms of its formative influence in design education. But aside from its aesthetics, one of the basic issues the Bauhaus worked on was the tension between commitments to research on basic artistic principles and to making saleable, machine-reproducible objects. This tension dogged it through its brief but highly influential 14-year existence. Constantly in turmoil, from its founding in the disastrous wake of World War I to suppression by the Nazis, the Bauhaus was never a “stable, communal, harmonious ensemble.”1 An important example of the research made possible in the Bauhaus context was the work of the “pure” artists who were employed to bring “exact experimental” methods to the realm of art.2 The painter Paul Klee, for instance, created a substantial body of theoretical and pedagogical work at the Bauhaus, much of it concerned with the problem of visual notation of dynamic form. This research-production was to a large degree out of sync with the immediate problems of mass production and housing. However, Klee’s sustained investigation of visual form in terms of dynamics proved to have enormous influence on other fields outside art, such as music composition and film animation, and on computer graphics decades later. All this work was carried out using traditional means of drawing and painting, and was concerned not with directly representing the Machine Age of the Bauhaus, but, more deeply, with the logical primitives needed for visually representing dynamic relationships. Klee’s work was deeply reflective of broader cultural issues of its time, including the intoxication with speed, transportation, and new models of time. But it was also beyond its time, in that it opened up a rich vein of “exact intuitions” (as Klee himself might have put it) whose implications were directly applicable to later practitioners working with newer technologies. The Bauhaus ideal of an “experimental mini-cosmos” mutually shaped by art, engineering, science, and philosophical concepts3 served as inspiration and template for subsequent organizations crossing the boundaries between technology and culture. This occurred partly through people, as many of the Bauhaus leaders immigrated to the United States. But, more generally, the idea of an institutional site for research to which master artists would attach themselves, if provisionally, has been influential, continuously invoked in the foundation of subsequent art/design and technology research centers since the 1960s. There were other important influences from the early 20th-century avant-garde on more recent art-technology movements. But the Bauhaus developed what sociologist Henri Lefebvre has called a “specific rationality,” which was new to the cultural sphere.4 This specific rationality—characteristic of the studio-laboratory— was inclusive, refusing a sharp distinction between the techno-scientific and the symbolic-expressive realms. For the modernist master composer Pierre Boulez in the 1970s, or the architectural theorist Heinrich Klotz in the 1980s, or computer scientist Pelle Ehn in the 1990s, the Bauhaus model inspired a holistic approach to co-development of new art and new technologies, both informed by theoretical research.5 |

FIGURE 5.1 Studio-laboratories in the 20th century.

AE Center—Ars Electronica, Austria

ATR—ATR Media Integration and Communications Systems Laboratories, Japan

E.A.T.— Experiments in Art and Technology

EVL–Chicago—Electronic Visualization Laboratory, University of Illinois, Chicago

GMD—German Research Center for Information Technology

I3 networks—Intelligent Information Interfaces, program of European Commission Fifth Framework for Research

IRCAM—Institut de Recherche et Coordination en Acoustique et Musique (Institute of Research and Coordination in Acoustics and Music), Paris

MIT–CAVS—Massachusetts Institute of Technology–Center for Advanced Visual Studies

NRC–NFB—National Research Council Canada–National Film Board

NTT–ICC—Nippon Telegraph and Telephone InterCommunication Center, Tokyo

PARC–PAIR—Xerox Palo Alto Research Center–Artist in Residence Program

V2—V2_Organisation, Institute for the Unstable Media, Rotterdam

WDR—West German Broadcasting Network

WNET—WNET Television Workshop Artist-in-Residence Program

ZKM—Zentrum für Kunst und Medien (Center for Art and Media), Karlsruhe, Germany

Rauschenberg and Bell Labs physicist Billy Klüver in New York in 1966. The goal of E.A.T. was to establish “an international network of experimental services and activities designed to catalyze the physical, economic and social conditions necessary for cooperation between artists, engineers and scientists.” The research role of the contemporary artist was understood by E.A.T. as providing “a unique source of experimentation and exploration for developing human environments

of the future.”5 At the same time, other Bell Labs scientists were also engaged in collaborative research, in computer graphics and vision, music, and acoustics.6 Also during the late 1960s, at MIT, the Hungarian artist and Bauhaus affiliate Gyorgy Kepes founded the Center for Advanced Visual Studies, providing a stable location for collaboration between artists in residence and university-based scientists and engineers. In the second phase, the earliest self-standing art-technology centers appeared—notably the Institut de Recherche et Coordination en Acoustique et Musique (IRCAM) in Paris—with a focus on the artistic rather than the industrial potential of information technology (IT) and electronics. Composer Pierre Boulez launched the IRCAM based on a conception of research/invention as the central activity of contemporary musical creation; Boulez invoked the “model of the Bauhaus” as cross-disciplinary inspiration for what he considered the necessary and inevitable collaboration between musicians and scientists.7 The modernist autonomy of the computer music research at IRCAM did not prevent it from also orienting its program toward a wider cultural public, aiming to put an otherwise forbidding musical language in the context of the history of 20th-century music and intellectual life.

The second phase, which incorporated festivals, exhibitions, commissions, and competitions of electronic art, marked an increased commitment of both public administrations and private corporations toward exposing the most radical media-based creativity to a wider public. As festivals such as Ars Electronica became global in scope beginning in the 1980s, so also plans were drawn up in most advanced industrial countries to establish permanent centers able to incorporate a dual research/development and public education mandate. Among the most conspicuous were the Zentrum für Kunst und Medien (ZKM) in Germany and the NTT InterCommunication Center in Japan.

In the United States, there has been no investment at a comparable scale in active commissioning, exhibition, and public programming of ITCP. Some smaller efforts have been made at a consistent level of quality and commitment, notably in science museums, such as the Exploratorium in San Francisco. New-media artists and techno-art engineers speak with a common voice in lamenting the lack of well-developed circuits for public exhibition, review, and systematic documentation. This was often expressed to the committee as the absence of European-style institutions in the United States that combine re

|

5 |

Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), 1969, Experiments in Art and Technology Proceedings, E.A.T., New York. |

|

6 |

Bell-Telephone, 1967, “Art and Science: Two Worlds Merge,” Bell Telephone Magazine, November/December. Also see Box 6.3 in Chapter 6. |

|

7 |

Pierre Boulez, 1985, Le modèle du Bauhaus. Points de repère, Editions Seuil, Paris. In terms of computer expertise, IRCAM depended heavily on the U.S. academic computer music community, initially duplicating the computer system and software in use at Stanford University’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics. |

search in contemporary media arts with large collections and public displays. Artists worry about a lack of contact with the American public, and, more specifically, seek intelligent and informed responses to created installations and wider professional and disciplinary associations.

Not that ZKM and other such centers are without critics. The German philosopher and critic Florian Roetzer analyzed the media-center bandwagon of the late 1980s, when he commented sardonically that “everywhere there are plans to inaugurate media centres, in order not to lose the technological ‘connection.’ . . . This new attention is supported by the diffuse intention to get on with ‘it’ now, the contents remaining rather arbitrary, so long as art, technology and science are somehow joined in some more or less apparent affiliation with business and commerce.”8 Roetzer was then not alone among critical intellectuals in harboring a deep ambivalence about these institutional developments, fearing that they would serve only to accelerate the public acceptance of automation in everyday life, on the one hand, and to co-opt artists—“with their purported creativity”—into becoming commercial application designers, on the other. As it turned out, explicitly designed linkages between art, research, and industrial innovation developed a good deal beyond Roetzer’s cynical prognostications, and rather quickly became the basis for the third phase of the contemporary studio-laboratory.

The third phase was marked by the establishment of the MIT Media Laboratory. Many observers would probably count the MIT Media Lab as the most successful, as well as widely imitated, model for industrially sponsored research on art, design, and new-media technologies. (Because of its connection to an academic institution, the lab is discussed in Chapter 6.) The Media Lab’s large-scale, precompetitive industrial consortia are global in scope and have inspired a number of institutional responses in other countries. For instance, the Swedish initiative of a network of six interactive institutes, loosely interacting but also differentiated according to technology and artistic focus, grew in large measure out of a national initiative to attract and retain a critical mass of researchers while still decentralizing the activity to both large and small cities.9

During the third phase, a number of technology companies attempted to harness artistic expertise to further corporate goals. For example, Interval Research Corporation assembled an unusually diverse research staff, including artists and filmmakers as well as computer and social scientists. Throughout the 1990s, Xerox Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) supported an in-house artist-in-residence

|

8 |

Florian Roetzer, 1989, “Aesthetics of the Immaterial? Reflections on the Relation Between the Fine Arts and the New Technologies,” Artware, catalog for the “Kunst und Elektronik” exhibition, Hannover, Germany. |

|

9 |

See <http://www.interactiveinstitute.se>. Also see the discussion in the section “Hybrid Networks,” below. |

There is an absence of European-style institutions in the United States that combine research in contemporary media arts with large collections and public displays.

program, whose intent, according to PARC director John Seely Brown, was to serve as “one of the ways that PARC seeks to maintain itself as an innovator, to keep its ground fertile and to stay relevant to the needs to Xerox.”10 Some of these efforts have had positive aspects, but few, if any, last very long. Much of the difficulty seems to be how to justify them in the corporate context, especially in difficult economic times. Interval Research is closed and PARC’s work is increasingly outside the ITCP domain.11

MULTIFACETED NEW-MEDIA ART AND DESIGN ORGANIZATIONS

This section reviews a few of the best-known examples of new-media art and design organizations, based mostly in Europe (given the lack of such organizations in the United States), in two categories: standalone centers and hybrid networks.12 Some of these examples might serve as learning experiences for the future establishment of similar U.S.-based organizations.

STANDALONE CENTERS

Among the most prominent standalone centers is the ZKM13 (a collection of commonly housed institutions involved in new-media art), which encompasses research and development institutes, a media art library, a media art museum, and a modern art museum. The ZKM regularly hosts talks, workshops, and conferences on issues in art history, technology policy, and cultural criticism of technology. A North American version of this model is the Banff Centre in Canada, although the scope of the Banff Centre extends beyond new-media work and its exhibition programs are limited. Other centers include Ars Electronica in Austria, the Center for Culture and Communication (C3) Foundation in Hungary, and the Waag Society in the Netherlands.

Established in 1988, the ZKM (Center for Art and Media) is an influential institution that plays an important role in the German cultural scene (ZKM has hosted the Bambis, for example, the German equivalent of the Emmy awards). Founded on the idea that giving

|

10 |

John Seely Brown, 1999, “Introduction,” p. xi in Art and Innovation: The Xerox PARC Artist-in-Residence Program, Craig Harris, ed., MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. |

|

11 |

See the section “Corporate Experiences with Information Technology and Creative Practices” below in this chapter for further discussion of corporate initiatives. |

|

12 |

Also see the discussion of funding organizations within the international context in Chapter 8. |

|

13 |

See <http://www.zkm.de/>. |

artists access to all of the hardware and software tools and programmers they need to realize their creative vision, ZKM’s research institutes maintain cutting-edge hardware and software and a staff of programmers and designers. Because of the depth of resources available to individuals who have a commission or residence at ZKM, artists are encouraged to experiment. The rarity of a (relatively) non-resource-constrained environment being offered by such an organization has resulted in ZKM attracting many established and well-known new-media artists. In addition to supporting art-oriented work, ZKM established two institutes with other foci—one institute with a focus on basic research and another with a focus on socioeconomic research.

Located within the mountains of Alberta, Canada, the Banff Centre hosts work that ranges from the visual arts to theater to music to media. An elaborate resource to facilitate creative thinking and production, the center provides artists with access to studios, technical resources, and trained and skilled production interns. When supporting a project, the center has sometimes been able to supply an artist with a highly trained collaborative team, which includes programmers and designers, to work with the artist until his/her project is completed.14 Using repeat invitations, Banff has a policy of developing relationships with people over time, and this has become a positive and even essential component of the center’s atmosphere. The environment is intense and intimate; in the mountains, people tend to hang out together, working, eating, and socializing. The downside of the residency experience tends to be stretched resources, both human and economic, that make it difficult to create continuous work flow. Technical team members are often working on multiple projects, sometimes making it very difficult to move a project forward and keep it coherent. In addition, the time limits on residencies mean that work must fit within the allotted time rather than developing and resolving at its own rate. How credit is given in teams has also become an issue, as there can be an unfortunate tendency to treat technical collaborators as a kind of service crew. Like ZKM, the Banff Centre has a history of intellectually stimulating seminars and conferences that bring together a broad variety of people from both the non-profit and commercial sectors of new media. At Banff these are often the top people in the field, and the center has become known for the cross-pollination among disciplines that it offers.

Ars Electronica,15 which is located in Austria, has a rich history of promoting collaborations involving art, technology, and society.

|

14 |

The Art and Virtual Environments seminar, for instance, included eight projects experimenting with virtual reality tools. As an example, one virtual reality installation was a murder mystery entitled “Archeology of a Mother Tongue” that involved a collaboration between Michael Mackenzie, a playwright and director working in Montréal, and Toni Dove, an artist based in New York (and a committee member). See Mary Anne Moser and Douglas MacLeod, eds., 1996, Immersed in Technology: Art and Virtual Environments, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. |

|

15 |

For more information, see <http://www.aec.at/>. |

Through a series of ventures dating back as far as 1979, it has established itself as a model for other organizations to follow. Ars Electronica consists of four major activities: the Ars Electronica Center, a media center showcasing art and technology projects; Futurelab, the center’s research and development arm; Festival, an annual festival focusing on the convergence of art and technology; and Prix, an international competition for “cyberarts.”

The Center for Culture and Communication (C3) Foundation16 in Budapest bills itself as an institution whose main focus is fostering cooperation among the spheres of art, science, and technology, as well as providing a space for innovative experiments and developments related to communication, culture, and open society. Begun in 1996 as a 3-year pilot project, C3 is the result of a cooperative effort of the Soros Foundation Hungary, Silicon Graphics Hungary, and Matáv (a Hungarian telecommunications company). In November 1999, C3— with the cooperation of its founders—became an independent, nonprofit institution. One of C3’s goals has been to assist with the integration of new technologies into Hungary’s social and cultural tradition. Along those lines, C3 has been involved in efforts to provide Internet access to many individuals and non-government organizations, as well as operating a free Internet café and offering free courses regarding how to use the Internet.

The Waag Society17 was established in 1994 in Amsterdam as a foundation whose research program is focused on the ways in which people express themselves through new and old media. The society has four distinct programs: creative learning, interfacing access, public research, and sensing presence. In addition, the society is also cooperating with partners from industry on several projects. Among these is PILOOT, a communications environment for people with mental disabilities.

Standalone new-media arts and design centers possess unique strengths and face special challenges. Among their strengths, they can offer both stability and freedom to creative people who need work space and technical support. But most such centers are small and resource-constrained. Many centers are based on artist-in-residence programs or colonies with a short-term orientation, and the accumulation of discrete projects with targeted, limited-time funding forms the research agenda. As people and money come and go, organizations may have difficulty sustaining long-term intellectual agendas and pursuing topics iteratively in a way that leads to new insights; therefore, they seldom are viewed as knowledge-building entities like corporations or university departments. They also may have difficultly in acquiring innovative (often expensive, at least for the budgets of many non-profits) technological capabilities. It is possible and desirable, but difficult, for centers to have real research programs with multiyear

|

16 |

For more information, see <http://www.c3.hu/>. |

|

17 |

For more information, see <http://www.waag.org/>. |

Standalone new-media arts and design centers possess unique strengths and face special challenges.

funding. One approach is to obtain sponsorship from the IT industry; another is to develop durable research partnerships with universities and corporations. Short-term partnerships (on a project basis) sometimes have been successful, as when corporations provide significant resources in a co-development project.

The optimal research strategy is not clear. Short-term programs can be valuable. Artists’ residencies are important as a way of democratizing access to technologies and networks of expertise that many artists might not otherwise be able to acquire.18 But an agenda dominated by discrete projects does not encourage the development of work with depth and richness. The other extreme of very rigid, long-term research agendas is likely no better, because such agendas presume that ITCP work can be clearly defined years in advance—a problematic assumption. At the level of the individual, as noted in Chapter 2, there is a tension between the time needed for playful exploration and conceptualization and the pressure for production. If standalone centers can strike the right balance among these competing pressures, they can fill unique ecological niches where ideas and new art forms are incubated successfully. Moreover, standalone centers assume greater importance in the overall scheme of studio-laboratories in light of the difficulties faced by applied ITCP activities in corporations, which are discussed in the last section of this chapter.19

HYBRID NETWORKS

The term “hybrid networks,” which has become popular in some parts of the ITCP community, refers to consortia of diverse organizations. These networks are a means of supporting cooperation and collaboration across disciplines and communities—if they can overcome the communication problems, varying criteria for success, and other difficulties inherent in ITCP collaborations (as outlined in Chapter 2). In Europe, as well as in Canada, hybrid networks have sought to assemble a critical mass of ITCP workers, coupled to industrial sponsors and public policy usually aiming to develop regional innovation

|

18 |

Despite the lack of multifaceted new-media arts organizations in the United States, there are artists’ residency programs within academia, such as at Arizona State University and the University of New Mexico, and smaller organizations such as Harvestworks in New York City. There are also local programs in many cities that provide access on a more limited basis to computers, skilled teachers, and other resources. |

|

19 |

New investments in physical infrastructures have recently been announced, though it is by no means certain how far some of them will be curtailed by economic cycles. In New York City, the Eyebeam Atelier (<www.eyebeam.org>) proposes a venue like the Ars Electronica Center. At Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, a $150-million-scale Experimental Media and Performing Art Center has been announced. The Presidio development in San Francisco is negotiating a transfer of space to LucasFilm for mixed-use “high tech cultural development.” See “Open Letter” to create an Arts Lab—a hybrid art center and research facility—at the San Francisco Presidio, available online at <http://www.naimark.net/writing/artslab.html>. |

clusters in creative industries. The decentralized network of technocultural centers supported by the federal government in Canada during the 1990s included the Banff Centre (discussed above), which used this support to initiate its significant investigation of virtual environments in partnership with university researchers and industry sponsors.20 The European Commission’s first round of hybrid research networks was focused on intelligent information interfaces (I3) and linked art centers, corporations, and national laboratories; continued work is being planned to support high-quality digital content and cultural-heritage preservation efforts.21

The I3 networks attempt to join art, product design, and academic research and development with corporate product development and market research. In addition, research networks for digital arts began to appear in the 1990s, consistent with a turn away from the stovepipe separation of R&D and commercialization. The concept is captured in the European Commission’s Fifth Framework Programme, which emphasizes cross-disciplinary work and features as a theme the “User-Friendly Information Society.”22 The European Cultural Backbone (ECB) mediates between the commercial, government, education, and the cultural sectors, facilitating cross-disciplinary projects by serving as an incubator. The ECB can act as a brokerage structure for mutual support and collaboration to bring together complementary initiatives, drawing upon and connecting local and regional networks of its members in Europe.23

In North America, the idea of consortia, networks, and sustained collaboration of this type is attracting greater attention. Examples include the U.S. federal government’s Digital Libraries Initiative Phase 224 and Internet2 project (both of which include some aspects of ITCP work); the Ford Foundation study in progress, “Art Technology Network” (grant to the Kitchen in New York for a feasibility study, 2001); the activities of the National Alliance for Media Arts and Culture (NAMAC), dedicated to encouraging film, video, audio, and online/ multimedia arts and promoting the collaborations of individual media artists;25 and, at the regional scale, the BRIDGES Consortium (University of Southern California with the Banff Centre). The Canadian government is also supporting regional innovation networks to be admin

|

20 |

Moser and MacLeod, eds., 1996, Immersed in Technology. |

|

21 |

See <http://www.cordis.lu/ist>. |

|

22 |

For information on the Fifth Framework, see <http://www.cordis.lu/fp5/home.html>. For further discussion, see Paul David, Dominique Foray, and W. Edward Steinmueller, 1999, “The Research Network and the New Economics of Science: From Metaphors to Organizational Behaviors,” The Organization of Economic Innovation in Europe, Alfonso Gambardella and Franco Malerba, eds., Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K., and New York. |

|

23 |

See <http://www.e-c-b.net/>. |

|

24 |

See Chapter 8 and <http://www.dli2.nsf.gov>. |

|

25 |

See <http://www.namac.org>. |

istered by CANARIE.26 Clearly there are opportunities to advance this concept further.

The establishment of additional collaborative networks is one way to increase connections between existing activity in experimental arts and design, cultural and presenting institutions, and the IT industries.27 But multiple projects are likely to be needed, stressing variously the mobility of people, exchange of know-how, circulation of art and design works, and transfer of technology. Furthermore, all of the institutions involved in such networks need an awareness of the kind of research-application/art-design-technology hybridity exemplified by the Bauhaus.28

OTHER VENUES FOR PRACTITIONERS

In addition to multifaceted new-media arts and design organizations, ITCP practitioners can access supportive resources through several mechanisms, principally virtual-space-based strategies and professional conferences.29 It is interesting to note that traditional arts and design organizations—museums, galleries, art and design fairs, magazines, and so on—are not the prime movers of these efforts. Rather, a patchwork of diverse entities has organized and funded the virtual strategies, and scientific and technical communities organize a number of the conferences.

VIRTUAL-SPACE-BASED STRATEGIES

A virtual-support infrastructure came into existence in recent years to assist individuals in accessing creative tools and communities, enable communication of various types, and provide shared space for collaboration and file storage and exchange. These organizations have been the most focused of any institutions on leveraging IT to achieve their goals. They tend to be not-for-profit cultural establishments.

|

26 |

CANARIE Inc. is Canada’s advanced Internet development organization. It is a not-for-profit corporation supported by its members, project partners, and the national government of Canada. CANARIE’s mission is to accelerate Canada’s advanced Internet development and use by facilitating the widespread adoption of faster, more efficient networks and by enabling the next generation of advanced products, applications, and services to run on them. See <http://www.canarie.ca/about/about.html>. |

|

27 |

See <www.thekitchen.org/FordFinal.pdf> for the basis for such a network design proposal. |

|

28 |

However, physical proximity still matters, and so hybrid networks that are constrained to a confined geographic area have advantages. See Chapter 7 for further discussion. |

|

29 |

And, of course, they have some access to organizations associated with academic institutions; see Chapter 6 for a discussion. |

A particular strength of these organizations is that they offer people access to spatially decentralized communities. The result is small, sharply focused groups with low overhead. Some of the better-funded organizations also try to host small offline events for members in an effort to strengthen the online community.

These organizations draw from a common pool of tools to support electronic communication. In general, they use widely available IT, such as directories, databases, online chat programs, discussion boards, and listservs, rather than specialized or state-of-the-art tools. The creation and support of e-mail listservs constitute a common mechanism for organizations that seek to foster community. These tools support, ultimately on a widespread basis, the online equivalent of the gallery, workshop, community center, and coffeehouse, sometimes simultaneously.

Internet-based environments for supporting creative work take many forms, including archives, portals, communities of practice, and virtual galleries. The Internet has made it much easier for grassroots organizations to identify, filter, and collect creative work.30 Directories (or portals or indexes), usually implemented through Web sites, aggregate pointers to a broad set of resources connected with a domain. Organizations pull together these pointers and then, using a taxonomy they have developed, sort them into categories from which Web pages are then made. For example, the Digital Arts Source (DAS),31 a “curated” index to new-media art, divides its site into 16 “departments” with titles such as digital art, sound, software, and tools. By entering one of these departments, a user opens a page to a listing of links to resources; links are opened within a new browser window, leaving the DAS site open in the background.

An example of a not-for-profit organization that leverages the use of IT to promote communication between professional and amateur new-media artists is Rhizome.org. Using the Internet as its primary medium, Rhizome carries out its mission of presenting artwork by new-media artists, providing a forum for critics and curators to foster critical dialogue, and archiving new-media art.32 The Rhizome ArtBase project provides selected Internet artists with dual-purpose server space to store their electronic art as well as the space to make it available for online viewing. Creating a taxonomy using metadata33 to tag the art based on its type, genre, and the technology used in its production, Rhizome has organized an extensive library of digital art.

|

30 |

These mechanisms can aid in validating and recognizing quality work (see the discussion in Chapter 7). |

|

31 |

|

|

32 |

See “what we do” at the Rhizome site, <http://rhizome.org/info>. |

|

33 |

Metadata are data about data. In information science, metadata are definitional data that provide information about, or documentation of, other data managed within an application or environment. |

A particular strength of not-for-profit cultural establishments is that they offer people access to spatially decentralized communities.

The communication and information capabilities of the Internet have allowed Rhizome to break down barriers caused by distance and to build the Rhizome community to more than 13,000 members representing more than 118 countries. To facilitate communication within such a large and diverse group, Rhizome provides a series of moderated and member-supervised digital resources that support many-to-many communication. Internet art news is made available to not-for-profit organizations that seek to provide a news service to their users but do not have the internal resources to do so.34

The principal mechanism used by Rhizome to promote asynchronous communication is to push information to individuals by using e-mail listservs—The Rhizome Digest and the Rhizome Raw list (equivalent to a conference call that lasts all day every day, this list is unfiltered and enables subscribers to exchange virtually an infinite number of messages almost in real time; messages are stored in a searchable archive). Nettime,35 a completely virtual service provided by Public NetBase t0, also consists of a series of e-mail lists, most notably Nettime-L. The organization’s goal is to provide space for the discussion of new communication technologies and their social implications. Formed in 1995, the listserv has resulted in a conference in 1997 and a book, Readme: ASCII Culture and the Revenge of Knowledge, published in 1999.

A number of online communities assist practitioners in ITCP-related fields in locating resources. For example, the Museum Computer Network36 is a non-profit organization dedicated to fostering the cultural aims of museums through the use of computer technologies. It serves individuals and institutions wishing to improve their means of developing, managing, and conveying museum information through the use of automation. It has hosted conferences with titles such as “Real Life: Virtual Experiences, New Connections for Museum Visitors.” The ArtSci project has led to an online resource called the ArtSci Index, intended to create a rich global database of resources and requests for individuals wishing to collaborate, barter, research, or fund collaborative projects involving science and art. A “matching” function assists with the filtering of data relevant to the user’s needs. In the architecture arena, ArchNet37 is designed as an online community for architects, planners, urban designers, landscape architects, architectural historians, scholars, and students, with a special focus on the Islamic world.

|

34 |

A syndication model is used in which an Internet art news “module” is added to Web sites for free. This module contains an introduction to a top story and a link to the Rhizome Web site, where the complete story is located. Through the use of HTML to call a JavaScript procedure on the Rhizome Web server, the top story changes daily on the syndicator’s Web site without the need for manual interference. |

|

35 |

See <http://www.nettime.org/>. |

|

36 |

See <http://www.mcn.edu/>. |

|

37 |

See <http://archnet.org>. |

Some of the organizations providing these services are for-profit. The Thing, an organization similar to Nettime, started operation in 1991 as an electronic bulletin-board system (BBS) for artists and has since evolved into a full-fledged telecommunications company while still maintaining its focus on art and artists. The Thing continues to provide BBS services, functioning as an Internet service provider (ISP) and maintaining and supporting radar, a selective calendar of New York art, performance, digital, video, and film events. Individuals and organizations from the art community of New York City contribute submissions to radar.

It is possible even for smaller centers and not-for-profit community organizations to access networked technologies that allow for multisite performance. Innovative uses of the Internet and desktop computer technology are producing an explosion of creativity in this area. Funding for smaller grassroots organizations allows the acquisition of both a basic level of technology such as desktop computers, software, and broadband connection possibilities, and the expertise to begin to bring skills to a new population of independent producers. Harvestworks Inc. in New York City is a small, not-for-profit organization with a sound studio, multimedia facilities for production, and classes in a broad area of new technology tools. It runs a Web-based composer’s database, a CD magazine, and an artists’ residence program that encourages experimental projects and helps to implement them. It has sponsored and supported a number of experiments in multisite performance that have accessed networking tools through collaborations with universities on Internet2 or through smaller theater and performance centers with more modest equipment.

PROFESSIONAL CONFERENCES

Professional conferences are another means of communicating and displaying the results of ITCP work and may be an ideal way to bring together cross-disciplinary groups of scientists, artists, designers, technical researchers, and others whose paths might not otherwise intersect. There are international symposia that touch upon ITCP, such as ArtSci,38 which explores how the discoveries of scientific research can combine with the powerful metaphors of art to influence society. Multimedia presentations have featured collaborative projects such as brain waves transmitted via the Internet; the presenters also have discussed issues relevant to ITCP, such as the opportunities and pitfalls of collaborating across disciplines.39 Another example is the International Computer Music Conference (ICMC), an annual conference

(since 1974) of the International Computer Music Association.40 The ICMC includes composers, performers, scientists, and engineers on a roughly equal footing and typically has technical sessions and two or more concerts every day. Papers are selected by peer review, and music is selected by a jury of peers. The 2002 Dokumenta conference included many works that use projective technologies and involved a number of participants from developing countries.

In addition to conferences such as ArtSci, ICMC, and Dokumenta, professional conferences that are relevant to ITCP are also rooted in scientific and technical disciplines. In computer science, the core group of conferences, many of them cross-disciplinary, are organized by professional societies, notably the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, including its Computer Society.41 Of particular relevance are the ACM’s annual conferences for the Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques (SIGGRAPH) and Special Interest Group on Computer-Human Interaction (SIGCHI). See Box 5.2. Specialized conferences related to ITCP are also held under the auspices of technical societies, such as the Creativity and Cognition conference held every third year at Loughborough University, an ACM SIGCHI international conference.42

A macro-level approach to communicating and promoting work that crosses disciplinary boundaries is exemplified by the U.S. National Academies’ Frontiers of Science and Frontiers of Engineering conferences. The former series, for example, brings together the best young scientists from a variety of fields to discuss cutting-edge research in ways that are accessible to colleagues outside their fields. The idea is to fertilize cross-disciplinary understanding and inspiration by exploring parallels and divergences between different research programs and protocols. One can envision a new venture based on this model called Frontiers in Creativity.

There are also a number of ad hoc conferences sponsored by professional organizations and universities aimed at bringing together scientists, humanists, artists, designers, and engineers to address topics related to IT. Examples include the First and Second Iteration Conferences sponsored by the School of Computer Science and Software Engineering at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, a juried competition that brought together musicians, artists, and humanists with computer scientists, physical scientists, and engineers to discuss projects recognized for their achievements in using digital technologies creatively.43 Oriented more toward research, the National Science Foundation, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and

|

40 |

See <http://www.computermusic.org>. |

|

41 |

There are also specialized professional societies that host relevant conferences, such as the American Association for Artificial Intelligence. |

|

42 |

|

|

43 |

|

BOX 5.2 Selected Conferences Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques Founded as a special-interest committee in the mid-1960s by Andries van Dam of Brown University and Sam Matsa of IBM, the Special Interest Group on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques (SIGGRAPH) was officially formed as a special-interest group of the Association for Computing Machinery in 1969.1 The SIGGRAPH’s premier event, its annual conference and exhibition, brings together artists, scientists, academics, and researchers from around the world working at the intersection of computer science and graphics. The conference has become an important venue, especially for companies producing products that assist the creative process (such as animation software and graphics acceleration cards). One of the more popular experiences is the SIGGRAPH Art Show, a place within the conference where new-media artwork is available for perusal by conference attendees.2 Special Interest Group on Computer-Human Interaction The Special Interest Group on Computer-Human Interaction (SIGCHI) is an international group of almost 5,000 specialists working in a variety of disciplines including human-computer interaction, education, usability, interaction design, and computer-supported cooperative work.3 Of special interest to members of SIGCHI is the intersection of such fields as user interface design, implementation and evaluation, human factors, cognitive science, social science, psychology, anthropology, design, aesthetics, and graphics. A key element of SIGCHI’s strategy is the organization and support of a series of cross-disciplinary conferences, many occurring annually. In addition to its main conference, “CHI: Human Factors in Computing Systems” (held annually since 1983), SIGCHI also sponsors conferences in areas such as creativity and cognition (annually since 1999), hypertext and hypermedia (annually since 1987), multimedia (annually since 1993), the design of interactive systems (annually since 1995), virtual reality software and technology (in conjunction with SIGGRAPH and occurring annually since 1997), and other areas where the hardware and software engineering of interactive systems, the structure of communication between human and machine, characterization and contexts of use for interactive systems, methodology of design, and new designs coexist.

|

Harvard University Art Museums jointly sponsored an invitational workshop in 2001 called “Digital Imagery for Works of Art.”44 The

|

44 |

The final report of the workshop is available at <http://www.dli2.nsf.gov/mellon/report.html>. This Web page also contains a link to a comment form seeking feedback, including links to ongoing efforts in the various areas emphasized in the report, as well as pointers to resources (collections, tools, and so on) that may be useful for future collaborative work. |

workshop was designed to bring together computer and imaging scientists who have been active in digital imagery research with a particular group of end users, namely research scholars in the visual arts, including art and architecture historians, art curators, conservators, and scholars and practitioners in closely related disciplines. The purpose was to explore how the research and development agenda of computing, information, and imaging scientists might more usefully serve the research needs of research scholars in the visual arts. At the same time, participants looked for opportunities where applications in the art history domain might inform and push IT research in new and useful directions. Other notable examples include the Millennial Open Symposium on the Arts and Interdisciplinary Computing (MOSAIC) 2000 that brought together people interested in the relationship between mathematics and the arts and architecture;45 the Archaeology of Multimedia conference at Brown University in November 2000; the Re: Play conference in November 1999;46 the International Symposium on Electronic Art (ISEA);47 and the Doors of Perception conference.48

PUBLIC DISPLAY VENUES

A variety of physical-place-based (or artifactual) and virtual-space-based techniques and strategies are used for the display of ITCP work for access by public audiences. Exhibitions, performance festivals, and presentations and lecture series seem to be the most common physical-place-based strategies. Museums, galleries, and other entities associated with physical places have featured new-media art for several years. In the United States, the promotion of this art form is guided by many of the established and better-known museums. By constructively adapting their space to include new-media art, both offline inside conventional exhibition spaces and online through the Web, and by commissioning work of this kind, these organizations are experimenting with new frameworks for display and presentation. For instance, since Internet art debuted at the 2000 Biennial, the Whitney Museum in New York City49 has increasingly supported new media inside its physical location (and on its Web site). Such efforts by traditional art museums are not without critics, who point out the limited allocation of resources or the artistic weaknesses of some shows that may be presented primarily to keep up with trends. Still, some strategies have proven to be both novel and artistically credible.

|

45 |

Held at the University of Washington, Seattle, in August 2000. See <http://www.cs.washington.edu/mosaic2000/>. |

|

46 |

|

|

47 |

|

|

48 |

|

|

49 |

See <http://whitney.org/>. |

The New Museum of Contemporary Art50 in New York has adapted place-based strategies—both indoors and outdoors—to accommodate ITCP work. The museum features an entire floor where visitors can drop in to read, think, talk, browse, and experience interactive art. Its Zenith Media Lounge is dedicated to the exhibition and exploration of digital art, experimental video, and sound works. This unique space, modest in physical size and budget, draws praise for its adequate technology infrastructure (i.e., computers, projectors, wiring, and so on) and staff support (i.e., system administrators, installers, and others) as well as an artistic focus ensured by staff curators bringing in guest curators to add new-media expertise. A group show, “Open_Source_Art_Hack,” which explored hacking practices, open source ethics, and cultural production to provide commentary about life in a networked culture, featured works such as an anti-war game, a packet-sniffing application, and an “ad-busting” project. The museum’s Education Department also organizes panel discussions, film and video series, and lectures to introduce challenging new concepts to a broad public.

Physical-place-based displays for ITCP work are also evident at popular technology-oriented museums, such as the Tech Museum of Innovation51 in San Jose, California. Visitors can make a digital movie using the latest tricks in animation, for example, visit with the roaming robot ZaZa, or engage in high-tech play in the Imagination Playground. A short distance up the coast, Exploratorium: The Museum of Science, Art, and Human Perception,52 housed in San Francisco’s Palace of Fine Arts, is designed to create a culture of learning. A collage of more than 650 blinking, beeping, buzzing exhibits invites visitors to make their own discoveries about the world.

The distinction between physical and virtual display approaches can be blurred in cases in which an organization uses both strategies, and the projects are interconnected—a not uncommon scenario. For example, some museum and gallery exhibitions take advantage of Web technology to enable fluid interchanges between virtual and real spaces. At the exhibition “010101: Art in Technological Times” at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA)53 in 2001, physical installation spaces were supplemented by computers at which gallery visitors could access essays by artists and theorists. Other exhibitions use virtual spaces as part of the artworks themselves, such as in interactive dramas that combine responses by actors in the physical space with online participants who collaborate to produce emergent narratives. See Box 5.3.

|

50 |

See <http://www.newmuseum.org/>. |

|

51 |

See <http://www.thetech.org/>. |

|

52 |

See <http://www.exploratorium.edu>. |

|

53 |

See <http://www.sfmoma.org/>. |

|

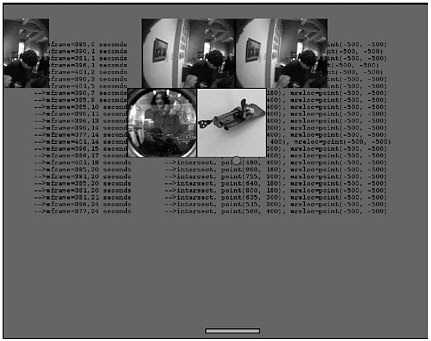

BOX 5.3 Computer and Sensor-based Art Installation Tiffany Holmes’s computer and sensor-based installation, “amaze@getty.org,” relies on “liveware”— that is, real-world and real-time viewer collaboration—not just hardware. Created for the exhibition “Devices of Wonder: From the World in a Box to Images on a Screen,”1 this networked system consisted of tiny spy cameras distributed throughout the gallery space to capture people looking at, and interacting with, other works in the show (such as the multiplying spectacles, book camera obscura, Engelbrecht Theater, and Mondo Nuovo peep show). The live video was ported using wireless technologies into a computer that integrated the imagery into a large montage displayed on a plasma screen encountered as one left the exhibition. The space around the plasma screen acted as the interface for the piece. In its resting state, with no viewer standing before it, the screen displays a panoramic image of Robert Irwin’s garden lying just outside the museum’s walls. When a viewer approaches the screen the animation changes. Slowly, the video is fractured by small rectangles. As they multiply, the sweeping image of the garden is replaced by even smaller images grabbed earlier by the hidden cameras. At the end of the piece, layers and layers of imagery fuse and then are broken apart in a simple game of breakout. See Figure 5.3.1. Conceptually, the piece draws on the metaphor of armchair travel, moving from material terrain into datasphere. The longer the viewer lingers in the gallery, the more she travels virtually, away from the seemingly infinite landscape into a series of highly localized private spaces that ultimately incorporate the watching subject into their confines. Unlike the hyper-illusionism of virtual reality, the experience makes the viewer acutely aware of how visual technology structures perception and how we structure visual technology.2

FIGURE 5.3.1 Screenshot from the “Devices of Wonder” real-time animation in which a computer-controlled breakout game removes the specific evidence of the localized surveillance imagery. Contributed by Tiffany Holmes, School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

|

Many organizations, from museums to professional associations, are eager to explore the possibilities that IT offers for communicating their work to peers and/or public audiences. But until recently, traditional museums and galleries have been slow to provide technological resources or exhibit space to creative talent whose primary medium is the Internet. Their initial online efforts have often focused on supporting activity, such as the digitization of existing collections and the use of the Internet as a medium for providing visitor information, promotion, and virtual gift shops. With that experience and further observation of how artistic expression involving IT is evolving, these organizations are rapidly becoming more open to exploring, supporting, and extending the techniques by which Internet creativity is produced and displayed. Increasingly, it is the strategies being tested, as opposed to whether they are doing any ITCP work at all, that differentiates these organizations from one another.

Examples of such efforts include the Whitney Museum’s ArtPort, which provides a portal to digital art and art resources on the Internet and also functions as an online gallery space for commissioned Internet and new-media art.54 This approach creates a dual strategy of supporting artists directly by commissioning projects, but also promoting the development of the Internet art domain in general by providing artists with cataloged resources. The Dia Center for the Arts began commissioning and exhibiting Web-based work in the mid-1990s.55 The SFMOMA is expanding its presence on the Internet through the development of its e•space program.56 With projects dating back to 1996, the e•space initiative supports Internet art via commissions and exhibition. Functioning as a portal to other Internet art or providing a gateway to resources is not one of the project’s main goals, although collaboration is. A recent illustration is CrossFade, which concentrates on the Web as a performance space for sound art, an international collaboration involving SFMOMA, the Walker Art Center, the Goethe-Institute, and ZKM.

New-media art is also beginning to make inroads in mainstream galleries, led largely by Internet art and the macro-trend of convergence among media and disciplines. Commercial galleries such as Postmasters57 and Sandra Gering58 are now showing and selling new-media art. There is even a commercial gallery dedicated to new media: Bitforms.59 For an alternate mechanism for matching up artists and collectors, see Box 5.4.

|

54 |

See <http://whitney.org/artport/>. |

|

55 |

|

|

56 |

|

|

57 |

The Postmasters Gallery features the work of Perry Hoberman (see Chapter 2) and Natalie Jeremijenko (a committee member). See <http://www.thing.net/~pomaga/>. |

|

58 |

The Sandra Gering Gallery presents the work of two individuals featured in this report: Karim Rashid and John Simon (see Chapter 2). Information about the gallery is available online at <http://www.geringgallery.com/>. |

|

59 |

See <http://www.bitforms.com>. |

Until recently, traditional museums and galleries have been slow to provide technological resources or exhibit space to creative talent whose primary medium is the Internet.

ITCP work creates new demands, because the work is often experimental and non-standard, and because the nexus of IT and creativity involves at least a limited breakdown of the separation between audience and performer.

|

BOX 5.4 Mixed Greens The for-profit organization Mixed Greens does not deal with new-media art specifically, but it has an interesting business model that might be extended to other contexts. Describing itself as an organization that discovers, supports, and promotes artists, this multimedia production company uses its Web site to facilitate communication between artists and collectors. This model allows collectors to get to know artists through a multimedia, personality-based approach to exhibiting art. There are artist documentitos (short videos about the artists), questions that users can answer to match them up with artists, and ways for users to contact artists and learn more about their work or perhaps start a discussion about anything from artistic influences to commissioning a work.1 One result is The Mix, a Web-based tool for constructing a personal environment for site members to get to know the artists and their work that Mixed Greens supports.

|

It is important to recognize that ITCP work creates new demands, because the work is often experimental and non-standard, and because the nexus of IT and creativity involves at least a limited breakdown of the separation between audience and performer. Traditional museums and galleries are often poor choices for the display of interactive and/or time-based work (e.g., narratives) because visitors stroll in and out and are not prepared for an experience of duration, nor are these spaces set up for specific start times. The rigidity of theaters with seats bolted to the floor does not work well, either. As a result, gallery spaces and performance and theater spaces need to be rethought to accommodate a less defined and more flexible practice. Theaters with flexible seating, movable partitions, projection systems with scalable, reconfigurable screen systems, and other innovations along these lines are making new work possible. Examples include the new-cinema theater of the Daniel Langlois Foundation for Art, Science, and Technology (DLF) in Montréal, where seats can be fixed or folded under to alter the more conventional cinema setup for special presentations and which has a state-of-the-art digital projection system. The Schaubuehne Theater in Berlin showcases another innovative design and is based on flexibility of scale, audience organization, and media tools for presentation. However, to a large degree, such innovations are not visible to the general public when they visit movie theaters, playhouses or opera houses, symphony halls, or other arts venues, which appear much as they have for the past decades. There would seem to be a rich set of opportunities for new approaches in these traditional venues. However, such new approaches do not replace traditional venues, which

|

BOX 5.5 Burning Man In contrast to much of the work done within research laboratories, academic departments, and arts organizations, Burning Man1 is an intriguing example of art and technology hybridized outside an institutional framework. In many ways, this event, held annually in the desolate environs of the Black Rock Desert in Nevada, is a counterpoint to what happens in the formal context of grants and research budgets, committees, and disciplines. The festival population, which in recent years has numbered almost 30,000 (mostly from the San Francisco Bay Area), includes thousands of engineers from Silicon Valley, from Cisco programmers to old-school hardware hackers. It is also a homing beacon for the West Coast’s ITCP community. It is a large-scale undertaking, all coordinated through electronic mail by a self-organizing web of techies, artists, lightning rods, and logistical magicians. The free-spiritedness of the event is belied by an impressive degree of networked organization. In a matter of weeks, this group of visionaries, tinkerers, and geeks erects not only a small city, with its own roads, sanitation, medical facilities, and electrical grid (all of which are dismantled in a matter of days—these libertarians run their show like a military operation), but also an eye-popping assortment of heavily technological artworks: towering amalgamations of metal and screens and sound feedback devices running artificial-life code, huge and programmable lighting arrays, explosive spectacles, and laser contraptions. Many of these art projects present unprecedented technical challenges, often requiring on-the-spot, midstream innovation (somehow, there are always enough soldering irons, duct tape, fuses, and volunteer laborers to go around—many of the larger installations combine the community effort of barn raising with the specialized expertise of Mission Impossible). In a sense, Burning Man embodies the “gift” economy that drives open-source software, with regard to atoms as well as bits. Burning Man also serves as a combination laboratory/audience for a grand techno-artistic experiment. Perhaps the most salient aspect of Burning Man, for technologists and artists within institutions, is the extent to which social capital can be leveraged at the intersection of technology and creative practices. What Burning Man has in abundance is not financial resources or institutional support or even human capital, in the sense that corporations do (i.e., salaried employees and administrative support). What it has, in abundance, is social capital—the relationships among people that give the event a reason to exist. Burning Man is a phenomenon that emerges from that network, a physical manifestation of the social and creative ties that go back years, sometimes decades. As a way of manifesting the human relationships that bind art and technology, and leveraging those relationships on a large scale, Burning Man is an object lesson for more formal organizations, both in vision and implementation.

|

may well remain valuable places to experience ITCP work. For an example of a distinctive non-traditional venue, see Box 5.5.

Performance art is also going online. Franklin Furnace,60 a non-profit arts organization that has long supported performance art and other alternative practices in the downtown New York art scene, went digital in the late 1990s and began supporting digital art through commissions and residencies. Also in New York, as part of an exhibit

associated with the New Museum, the Surveillance Camera Players performed in front of a Webcam; the audience could view the performance in person at various locations, including the New Museum window on Broadway, or online. The Brooklyn Academy of Music,61 which gave its first performance in 1861 and has a reputation for changing with the times, has hosted online interactive documentaries that explore and offer insights into the ideological foundation and creation of work presented on stage. For example, “Under_score: Net Art, Sound and Essays from Australia” exhibits the works of nine artists with portals to sonic experimentation. Thematically centered on the body, these projects confront what it means to be sexed up, desired, gendered, and identified under electronic conditions. Another documentary chronicles the development of the work Love Songs by choreographer David Roussève and his company REALITY, and presented as part of BAM’s 1999 Next Wave Festival. Users have access to rehearsal footage, interviews with Roussève, company information, and discussions about the work.62

Some experiments with art presentation provide venues for Internet-based research that push the envelope in terms of how technology can be used to augment social environments. The Museum of Modern Art (MOMA)63 in New York City has supported a number of new-media artists through commissions and has used the Internet to engage artists to overcome obstacles linked to space and time. For instance, its Conversations with Contemporary Artists program, originally presented offline, recently was replicated online. Projects constrained by time such as Time Capsule have been migrated online as well.

Similarly, the Walker Art Center is focusing not on how virtual space enables the display of content, but rather on how it facilitates information sharing and collaboration in the creation of art—a kind of Internet-based creative research and development.64 Built in 1971, the center concentrates on supporting the development and exhibition of modern art. By supporting film/video, performing, and visual arts, the center takes a global, cross-disciplinary, and diverse approach to the creation, presentation, interpretation, collection, and preservation of art.65 The new-media initiatives of the center seek to achieve two goals: Its Gallery 9 project promotes project-driven exploration through digital-based media, whereas the SmArt project concentrates on information architecture and the role that it might play in facilitating access to the collections and activities of the center.

|

61 |

See <http://www.bam.org>. |

|

62 |

One reviewer, however, suggested that BAM is pulling back from such digital initiatives. |

|

63 |

See <http://www.moma.org/>. |

|

64 |

|

|

65 |

It is important to note that efforts to collect and display ITCP work run into the formidable challenges posed by digital technology. (See Chapter 7.) For instance, the likely inability to distinguish between an original and a copy will have a profound effect on museums, one rivaling the effect that photographic reproduction had on art.66 This will cause a paradigm shift in how a museum views its holdings (as pimarily unique original objects) and how it certifies their authenticity. Conservationists will also have to shift from the paradigm of repairing and saving a physical object to that of maintaining a set of disembodied artistic content over time. Indeed, it has been said that new-media art questions the most fundamental assumptions of museums: What is a work? How do you collect? What is preservation? What is ownership?67

CORPORATE EXPERIENCES WITH INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY AND CREATIVE PRACTICES

A number of industries depend heavily on, and derive substantial profits from, ITCP activities. This may be most obvious in entertainment, or “content-based” corporations. For example, filmmaking has driven and adopted advances in both technical and creative achievement, and computer games would not exist at all without ITCP (the collaborative nature of these industries is discussed in Chapter 2). Yet technology companies seem to be less successful in importing and applying art and design knowledge to their activities. Some companies have experimented with specialized arts centers, artist-in-residence programs, or short-term arts projects, with mixed results.

Two less than successful initiatives were mentioned earlier in this chapter: Interval Research and Xerox PARC’s Artist-in-Residence program. Lucent’s one-of-a-kind collaboration with the Brooklyn Academy of Music, which produced the acclaimed Listening Post (described in Chapter 2), is now defunct, a victim of the company’s financial woes. Tough economic times in 2001 and 2002 have led to the downsizing of the Nippon Telegraph and Telephone InterCommuni

cation Center (ICC)68 and folding of the Canon ArtLab,69 both in Tokyo.

But some IT companies have experienced ventures into art and design that generate qualitative and tangible benefits. The Philips Vision of the Future is one example of a large-scale, successful project that integrated technology development with design practices and human-centered disciplines such as anthropology.70 (See Box 5.6.) Another example is IBM Corporation’s Computer Music Center (CMC), which from 1993 to 2001 focused on the intersection of computer science and music as a research testbed, beginning with an effort to develop the underlying technology for KidRiffs, a consumer software product that was eventually marketed and sold. Over time, the center grew to focus on interactive music composition tools, seeking to understand the special demands that large-scale creative endeavors, such as film scoring, place on software. Research on visual programming languages, interactive graphics, real-time systems, and audio identification provided a diverse backdrop for the core music composition work. Although the CMC was ultimately closed, it contributed to product development, public relations, and the company’s portfolio of intellectual property.71 The QSketcher system, for example, developed in close collaboration with faculty and composers affiliated with the Berklee College of Music, pioneered several HCI mechanisms.72 The

|

68 |

Established in 1997, ICC sought to “encourage the dialogue between technology and the arts using a core theme of ‘communication’” and “to become a network that links artists and scientists worldwide, as well as a center for information exchange.” Both a museum open to the public and a research lab, ICC was a place for the conceptualization, introduction, and testing of advanced media art communication technologies. But ICC was more than just a setting where artists and technologists congregated to create media art to be displayed in a museum or gallery. Offering workshops, performances, symposiums, and publishing, the center went beyond exploring the possibilities of new forms of communication to attempt to educate and expose the public to the capabilities of the art and technology intersection. See <http://www.ntticc.or.jp>. |

|

69 |

ArtLab was a corporate lab focused on the integration of the arts and sciences, primarily by encouraging new artistic practices using digital imaging technologies. The “factory” (laboratory) employed computer engineers using Canon digital products in interaction with artists in residence to produce new digital art works. The studio portion of the program has presented exhibitions of the works developed in-house. In 1995, seeking to introduce multimedia works to the general public, the ArtLab began its Prospect Exhibitions program, which also provides access to the work of multimedia artists and creators outside the ArtLab. Workshops and lectures on new communications technologies and practices were also organized on an ad hoc basis and are both national and international in scope. See <http://www.canon.co.jp/cast/artlab/index.html>. |

|

70 |

|

|

71 |

Sometime prior to the closure of the center, IBM determined that a venture into the music software tools market was unlikely but continued to support the center as a fundamental research effort. |

|

72 |

See Steven Abrams, Joe Smith, Ralph Bellofatto, Robert Fuhrer, Daniel Oppenheim, James Wright, Richard Boulanger, Neil Leonard, David Mash, and Michael Rendish, 2002, “QSketcher: An Environment for Composing Music for Film,” pp. 157-164 in Proceedings of the Fourth Conference on Creativity and Cognition, Loughborough University, U.K., ACM Press, New York. |

center hosted well-known musicians, served as a recruiting tool, and contributed to education and outreach programs. The venture also produced a stream of inventions, including 16 patents filed over the center’s last 4 years.73