III

Global Challenges

The rate of growth of the world’s population is predicted to slow in the 21st century, but since the beginning of the 20th century the number of people in the world has more than quadrupled—from 1.6 billion to nearly 7 billion—and world population is expected to rise to more than 9 billion by 2050.

The sheer fact of all those people striving to achieve a suitable quality of life means that stress on the resources of our planet is bound to increase. Climate change, with its attendant effects on weather patterns; the displacement of human populations due to political conflict or worsening environmental conditions; and the expansion of settlements into former wilderness areas are all global trends that carry with them significant implications for the nature of humans’ relationship with microbes.

Globalization

Today’s world is a global village, with growing concentrations of people in huge cities, mass migrations forced by social or economic pressures, and accelerating commerce and travel. An estimated 1.8 million airline passengers cross international borders daily, creating routes by which human infections can radiate around the world within hours. The crates and containers in which goods are shipped worldwide provide safe passage for disease vectors and animal pathogens. Building roads in previously roadless areas brings people into contact with new environments and potentially new pathogens. Cruise ship travel has increased, bringing together—often in confined spaces—thousands of people from diverse geographic regions (including countries with immunization requirements that differ significantly from those of the various sites where ships disembark). And as adventure travelers intrude on new environments and make contact with exotic wildlife, they may encounter microbes that have never before been recognized as human pathogens.

The movement of people around the globe, depicted here in a map of air traffic among the 500 largest international airports, can lead to the rapid spread of infectious disease.

In this rapidly shifting and interconnected world, infectious agents continually find new niches. The 2009 “swine flu” pandemic starkly illustrated the impact of globalization and air travel on the movement of infectious diseases—with the infection spreading to 30 countries within 6 weeks and to more than 190 countries and territories within months.

The human population is undergoing a mass migration from the countryside to “megacities.” Throughout history, big cities have been great incubators of infections—with outbreaks of respiratory, gastrointestinal, meningeal, and skin infections becoming common in crowded urban settings. Substandard housing and inadequate sewage and water management systems incubate disease vectors such as mosquitoes and rats. Poor access to health care services worsens the spread of infection.

Globalization of the food supply has spread disease caused by bacteria such as Salmonella and E. coli O157:H7. The United States, for example, imports about 20 percent of its fresh vegetables, 50 percent of its fresh fruits, and more than 80 percent of its fish and seafood. As wealthy nations demand such foods year-round, the increasing reliance on producers abroad means that food may be contaminated during harvesting, storage, processing, and transport—long before it reaches overseas markets.

Food is not the only globally traded product to set off waves of infection. In 1999 the fungus Cryptococcus gattii emerged on Vancouver

Sao Paulo, Brazil—a modern megacity.

Island, British Columbia, Canada, causing a growing epidemic of human and animal infections and deaths. It has since spread to the Pacific Northwestern United States. The fungus, which causes deadly infections of the lung and brain, had previously been found only in tropical or subtropical climates in such regions as Africa, Australia, Southeast Asia, and the South Pacific. The exact origins of this outbreak remain a mystery, but some researchers suggest that the fungus may have been introduced through the importation of contaminated trees, shoes, wooden pallets, or shipping crates.

Climate Change

Global climate change is expected to contribute to the worldwide burden of disease and premature deaths. Scientists predict that rising average temperatures in some regions will change the transmission dynamics and geographic range of cholera, malaria, dengue fever, and tick-borne diseases. Increased precipitation may raise the number and productivity of breeding sites for vectors such as mosquitoes, ticks, and snails. Rising atmospheric and surface temperatures are also increasing the intensity, frequency, and duration of heavy precipitation and flooding events, which may raise the risk of diarrheal diseases and vector-borne infections.

A number of diseases—such as malaria, dengue fever, and viral encephalitis infections—are highly sensitive to changes in the environment. The 1993 outbreak of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (a severe acute respiratory disease) in the Southwestern United States provides a dramatic example of how acute weather events can promote disease transmission. The outbreak was traced to a steep increase in the population of deer mice that carry the virus—an increase caused by heavy rains after 6 years of drought, which led to an abundance of food sources for the deer mice. West Nile virus emerged in the Eastern United States in 1999, during the hottest and driest summer in a century. Subsequent outbreaks in the Midwest in 2003, 2005, and 2006 also coincided with heat waves. Scientists believe that hot weather may speed up both the breeding cycle of mosquitoes and replication of the virus in insects’ guts.

Several recent studies have examined the relationship between the occurrence of infectious diseases and short-term climate variation, in particular the influence of the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) cycle on the transmission of vector-borne and nonvector-borne infections such as malaria, dengue fever, and cholera. ENSO is the irregular cycling of surface water temperatures between warm and cool phases across parts of the Pacific Ocean. Global climate change is expected to intensify ENSO-related climate variability.

Scientists are currently debating the future effects of climate change on vector-borne disease. Some

experts predict that many vector-borne diseases will expand their range to higher elevations and latitudes in response to global warming; others claim that human impacts on the local ecology, such as deforestation and water use and storage, have a far stronger influence on the frequency and range of vector-borne infections.

A secondary effect of climate change also promotes infectious disease. Human migration often follows extreme weather or weather-associated events, including hurricanes, cyclones, fires, drought, and floods. The risk of disease outbreaks increases after such disasters due to population displacement, resulting in unsafe food and water, crowding, and poor access to health care.

Ecosystem Disturbances

Whenever animals (including humans), plants, and microbes are introduced into new places, they can disrupt ecosystems in ways that increase the potential for infectious disease outbreaks. Such changes can be difficult to predict and even more daunting to prevent. The term “invasive species” is widely used to describe plants and animals that, when introduced to and established in new environments, spread aggressively. Invasions of disease-causing microbes play out in similar ways.

The edges or transition zones between two adjacent ecological systems appear to be “hot spots” for disturbance-induced disease emergence. Examples of such transition zones include the border of human settlements, as well as natural transitions between forests and plains, shorelines, and tree lines. Because of the massive expansion of human settlements into natural, uninhabited ecosystems, these ecological transition zones now dominate much of the geography of the world’s tropical developing regions.

When humans move into new environments, microbes that occur in the native wildlife population without causing apparent ill effects may adapt and jump to people. Scientists believe that the Ebola virus—first identified in a western equatorial province of Sudan and in a nearby region of Zaïre (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) in 1976—naturally resides in the rainforests on the African continent and in the Western Pacific. Laboratory observation has shown that bats experimentally infected with Ebola do not die, and this has raised speculation that these mammals may play a role in maintaining the virus in the tropical forest. Closer to home, Lyme disease surfaced when abandoned farmland in the Northeastern United States reverted to fragmented forest land—a perfect home for deer and the deer tick that carries the bacterium associated with Lyme disease.

The clearing and settlement of tropical rainforests has exposed woodcutters, farmers, and ecotourists to new vector-borne diseases. Deforestation also creates new habitats for pathogens and vectors. In South America, for instance, epidemic malaria has broken out in recently clear-cut areas where mosquitoes now thrive.

The construction of large dams can cause profound ecological changes that increase vector-borne diseases. In tropical and subtropical nations the development of large water projects has been associated in some areas with a rise in malaria and schistosomiasis, both parasitic infections.

Poverty, Migration, and War

Throughout history, poverty and infectious disease have been intimately connected. In makeshift and overcrowded shantytowns and slum neighborhoods located on the outskirts of major cities in the developing world, lack of access to clean water and improper sanitation services spread diarrheal diseases. Worldwide, 884 million people do not have access to an adequate water supply, and about three times that number lack basic sanitation services. An estimated 2 million deaths a year can be attributed to unsafe water supplies; about 90 percent of those who die from diarrheal diseases are children in developing nations.

People in poor nations often suffer from more than one infection, because poverty breeds many diseases at once, including HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, respiratory and intestinal infections, and neglected diseases of poverty such as intestinal worms, Chagas disease, and dengue fever. Pneumonia, diarrhea, and malaria are among the leading causes of death in the developing world in children under the age of five. When there is a lapse in political will to support disease prevention efforts, such as childhood vaccinations, disease can emerge rapidly, as seen in the spread of polio from northern Nigeria to more than 20 other countries.

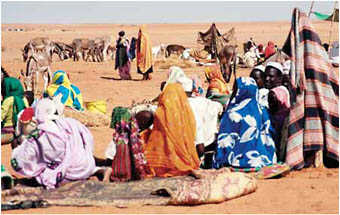

Refugee camp in Sudan.

In addition, developing nations face public health hurdles such as weak health care systems and long distances to health care facilities. Limited availability of drugs, or widespread use of poor-quality or counterfeit medications, has led to drug resistance in the poverty-associated infections of HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria.

Growing numbers of people are moving within and across national borders after being forced from their homes by war, poverty, or famine. According to some estimates, 1 billion people could be displaced by 2050. Displaced people often bring their livestock, plants, or companion animals with them, increasing the variety of pathogens and vectors that accompany such journeys. Such refugees frequently live in crowded, unsafe conditions that exacerbate the transmission of infectious diseases. Rural to urban migration, for example, has led to increased HIV transmission in Africa.

Bioterrorism

Bioterrorism is the deliberate release of viruses, bacteria, toxins, or other agents to cause illness or death in people, animals, or plants. According to experts, the threat of global bioterrorism is increasing. In October 2001, bioterrorism became a reality when letters containing powdered anthrax were sent through the U.S. Postal Service. The attack caused 22 cases of illness, 5 of which resulted in death, and widespread fear.

Bacillus anthracis, the agent of anthrax.

Biological agents are in some ways the perfect weapon of terror. They can be spread through the air, water, or food. Terrorists may choose these agents because they can be extremely difficult to detect and do not cause illness for several hours to several days after exposure, meaning that public health officials may not notice the attack until it is too late. Deadly pathogens are highly accessible. With the exception of smallpox, they all occur naturally in the wild—in soil, air, water, and animals. And the skills and equipment for making a biological weapon are widely known because they are the same as those required for cutting-edge work in medicine, agriculture, and other fields.

An investigator carefully examines one of the letters tainted with anthrax following the 2001 attack in the United States.

High-priority organisms or toxins that pose the greatest risk to national security are known as Category A agents, according to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). These deadly pathogens could be readily spread in the environment or transmitted from person to

person, triggering public panic and requiring special public health precautions.

Many public health officials believe that anthrax is the bioweapon of greatest concern—although in the case of the 2001 anthrax mailings in the United States there was less morbidity and mortality than many feared would occur. The infection is caused by Bacillus anthracis, a bacterium that forms spores. Anthrax does not spread from person to person but rather by hard-coated bacterial spores that spring to life under the right conditions. Anthrax can cause skin lesions and gastrointestinal disease. Inhalation anthrax is the rarest form of the infection—and may be the most difficult to treat.

Another disease of concern is smallpox, a serious, contagious, and sometimes fatal infection. Smallpox was officially declared eradicated from the globe in 1980, after an 11-year WHO vaccination campaign—the first human disease to be eliminated as a naturally spread contagion. Once the disease was gone, routine vaccination of the general public was stopped. Today, the virus remains only in laboratory stockpiles. But in the aftermath of the events of September and October 2001, concern has grown that the smallpox virus might be used as an agent of bioterrorism.

Another threat—the botulinum toxin—is the most lethal compound known. The nerve toxin is produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. Researchers estimate that as little as a gram of aerosolized botox could kill more than 1.5 million people.

NIAID is developing tools to detect and counter the effects of a bioterrorist attack, including vaccines to immunize the public against diseases caused by bioterrorism agents, diagnostic tests to help first responders and other medical personnel rapidly detect exposure and provide treatment, and therapies to help patients exposed to bioterrorism agents regain their health.

![]()

Awareness of disease threats fostered by changing patterns of human existence and behaviors is the first step toward mitigating their effects. The following section explores what we can do, individually and collectively, to address risks posed by this evolving relationship between humans and microbes.