Small businesses continue to be a major driver of innovation and economic growth,1 despite the challenges of changing global environments and the impacts of the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent recession.2 In the face of these challenges, supporting innovative small businesses in their development and commercialization of new products is essential for U.S. competitiveness and national security.

Created in 1982 through the Small Business Innovation Development Act, the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program remains the nation’s largest innovation program for small business. The SBIR program offers competitive awards3 to support the development and commercialization of innovative technologies by small private-sector businesses. At the same time,

__________________

1See Z. Acs and D. Audretsch, “Innovation in large and small firms: An empirical analysis,” The American Economic Review, 78(4):678-690, 1988. See also Z. Acs and D. Audretsch, Innovation and Small Firms, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1991; E. Stam and K. Wennberg, “The roles of R&D in new firm growth,” Small Business Economics, 33:77-89, 2009; E. Fischer and A.R. Reuber, “Support for rapid-growth firms: A comparison of the views of founders, government policymakers, and private sector resource providers,” Journal of Small Business Management, 41(4):346-365, 2003; M. Henrekson and D. Johansson, “Competencies and institutions fostering high-growth firms,” Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 5(1):1-80, 2009.

2See D. Archibugi, A. Filippetti, and M. Frenz, “Economic crisis and innovation: Is destruction prevailing over accumulation?” Research Policy, 42(2):303-314, 2013. The authors show that “the 2008 economic crisis has severely reduced the short-term willingness of firms to invest in innovation” and also that it “led to a concentration of innovative activities within a small group of fast growing new firms and those firms already highly innovative before the crisis.” They conclude that “the companies in pursuit of more explorative strategies towards new product and market developments are those to cope better with the crisis.”

3SBIR awards can be made as grants or as contracts. Grants do not require the awardee to provide an agreed deliverable (for contracts this is often a prototype at the end of Phase II). Contracts are also governed by Federal contracting regulations which are considerably more onerous from the small business perspective. Historically, all DoD and NASA awards have been contracts; all NSF and most NIH awards have been grants, and DoE has used both vehicles.

the program provides government agencies with technical and scientific solutions that address their different missions.

Currently, the program provides funding in three phases:

- Phase I provides limited funding (up to $100,000 prior to the 2011 reauthorization and up to $150,000 thereafter) for feasibility studies.

- Phase II provides more substantial funding for further research and development (typically up to $750,000 prior to 2012 and $1 million after 2011 reauthorization).4

- Phase III reflects commercialization without providing access to any additional SBIR funding, although funding from other federal government accounts is permitted.

Congress mandated four goals for the program: “(1) to stimulate technological innovation; (2) to use small business to meet federal research and development needs; (3) to foster and encourage participation by minority and disadvantaged persons in technological innovation; and (4) to increase private sector commercialization derived from federal research and development.”

Research agencies have pursued these goals through the development of SBIR programs that in many respects differ from each other, utilizing the administrative flexibility built into the general program to address their unique mission needs.

SBIR awards are highly competitive. In recent years, across all Department of Defense (DoD) components, about 13 percent of Phase I applications resulted in an award.5 Phase II could (before the 2011 reauthorization) be awarded only to projects that had successfully completed Phase I (and at DoD, again before 2011, companies had to be invited to apply for a Phase II award). Across all components, less than 50 percent of Phase II applications were successful. Overall, fewer than 6 percent of Phase I applications resulted in a Phase II award.

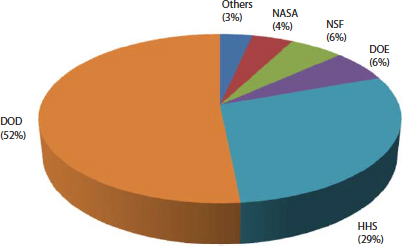

Over time, through a series of reauthorizations, SBIR legislation has required federal agencies with extramural research and development (R&D) budgets in excess of $100 million to set aside a growing share of their budgets for the SBIR program. Reaching a set-aside of 2.5 percent by fiscal year (FY) 2010, the 11 federal agencies administering the SBIR program were disbursing $2.24 billion dollars a year.6 Five agencies administer greater than 96 percent of SBIR/Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) funds: DoD, Department of Health and Human Services (HHS; particularly the National

__________________

4All resource and time constraints imposed by the program are somewhat flexible and are addressed by different agencies in different ways. For example, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and to a much lesser degree DoD have provided awards that are much larger than the standard amounts, and NIH has a tradition of offering no-cost extensions to see work completed on an extended timeline.

5DoD data provided to the National Research Council.

6Small Business Association (SBA) SBIR/STTR annual report, <http://www.sbir.gov/>, accessed November 1, 2013.

Institutes of Health [NIH]), Department of Energy (DoE), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and National Science Foundation (NSF) (see Figure 1-1).

In December 2011, Congress reauthorized the program for a further 6 years,7 with a number of important modifications. Many of these modifications—for example, changes in standard award size—were based on recommendations made in a 2008 National Research Council (NRC) report on the SBIR program, a study mandated as part of the program’s 2000 reauthorization.8 The 2011 reauthorization also called for further studies by the NRC.9

In a follow-up to the NRC’s first-round assessment, described in more detail below and which resulted in eleven reports10 including the 2008 report cited above, the DoD Office of Small Business (OSB) requested the NRC to provide a subsequent round of assessment, focused on operational questions with a view to identifying further improvements to the program.

This introduction provides a context for analysis of the program developments and transitions described in the remainder of the report. The first section provides an overview of the program’s history across the federal government. This is followed by a summary of the major changes mandated through the 2011 reauthorization and the subsequent Small Business Administration (SBA) Policy Directive; a review of the program’s advantages

__________________

7Section 5137 of PL 112-81.

8National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2008. The National Research Council’s first-round assessment of the SBIR program was mandated in the SBIR Reauthorization Act of 2000, Public Law 106-554, Appendix I-H.R. 5667, Section 108.

9The National Defense Reauthorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012, Public Law 112-81, Section 5137.

10National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2004; National Research Council, SBIR—Program Diversity and Assessment Challenges: Report of a Symposium, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2004; National Research Council, SBIR and the Phase III Challenge of Commercialization: Report of a Symposium, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2007; National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the National Science Foundation, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2007; National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the Department of Defense, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009; National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the Department of Energy, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2008; National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2008; National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009; National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the National Institutes of Health, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009; National Research Council, Venture Funding and the NIH SBIR Program, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009; and National Research Council, Revisiting the Department of Defense SBIR Fast Track Initiative, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009.

FIGURE 1-1 SBIR/STTR funding, FY2010.

SOURCE: <http://www.sbir.gov>, accessed November 1, 2013.

and limitations, in particular the challenges faced by entrepreneurs using (and seeking to use) the program and by agency officials running the program; and a summary of the technical challenges facing the NRC assessment and the committee’s solutions to those challenges.

PROGRAM HISTORY AND STRUCTURE11

During the 1980s, the perceived challenge of Japanese industrial growth in sectors traditionally dominated by U.S. firms—autos, steel, and semiconductors—led to serious concerns about U.S. competitiveness.12 A key concern was the perceived failure of American industry “to translate its research prowess into commercial advantage.”13 Although the United States enjoyed dominance in basic research—much of which was federally funded—applying this research to the development of innovative products and technologies

__________________

11Parts of this section are based on the NRC’s previous report on the DoD SBIR program, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the Department of Defense, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009.

12See J. Alic, “Evaluating competitiveness at the office of technology assessment,” Technology in Society, 9(1):1-17, 1987, for a review of how these issues emerged and evolved within the context of a series of analyses at a Congressional agency.

13D.C. Mowery, “America’s industrial resurgence (?): An overview,” in National Research Council, U.S. Industry in 2000: Studies in Competitive Performance, D.C. Mowery, ed., Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1999, p. 1. Other studies highlighting poor economic performance in the 1980s include M.L. Dertouzos et al., Made in America: The MIT Commission on Industrial Productivity, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1989; and O. Eckstein, DRI Report on U.S. Manufacturing Industries, New York: McGraw Hill, 1984.

remained challenging. As the great corporate laboratories of the post-war period were buffeted by change, new models such as the cooperative model utilized by some Japanese kieretsu offered new sources of dynamism and more competitive firms.

At the same time, new evidence emerged to indicate that small businesses were an increasingly important source of both innovation and job creation. 14 This evidence reinforced recommendations from federal commissions dating back to the 1960s, that is, that federal R&D funding should provide more support for innovative small businesses (which was opposed by traditional recipients of government R&D funding).15

Early-stage financial support for high-risk technologies with commercial promise was first advanced by Roland Tibbetts at the National Science Foundation (NSF). In 1976, Mr. Tibbetts advocated for shifting some NSF funding to innovative technology-based small businesses. NSF adopted this initiative first, and after a period of analysis and discussion, the Reagan administration supported an expansion of this initiative across the federal government. Congress then passed the Small Business Innovation Research Development Act of 1982, which established the SBIR program.

Initially, the SBIR program required agencies with extramural R&D budgets in excess of $100 million16 to set aside 0.2 percent of their funds for SBIR. Program funding totaled $45 million in the program’s first year of operation (1983). Over the next 6 years, the set-aside grew to 1.25 percent.17

The SBIR Reauthorizations of 1992 and 2000

The SBIR program approached reauthorization in 1992 amidst continued worries about the U.S. economy’s capacity to commercialize inventions. Finding that “U.S. technological performance is challenged less in the creation of new technologies than in their commercialization and adoption,” the NRC recommended an increase in SBIR funding as a means to improve the economy’s ability to adopt and commercialize new technologies.18

__________________

14See S.J. Davis, J. Haltiwanger, and S. Schuh, Small Business and Job Creation: Dissecting the Myth and Reassessing the Facts, Working Paper No. 4492, Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 1993. According to Per Davidsson, these methodological fallacies, however, “ha[ve] not had a major influence on the empirically based conclusion that small firms are overrepresented in job creation.” See P. Davidsson, “Methodological concerns in the estimation of job creation in different firm size classes,” Working Paper, Jönköping International Business School, 1996.

15For an overview of the origins and history of the SBIR program, see G. Brown and J. Turner, “The federal role in small business research,” Issues in Science and Technology, Summer 1999, pp. 51-58.

16That is, those agencies spending more than $100 million on research conducted outside agency labs.

17Additional information regarding SBIR’s legislative history can be accessed from the Library of Congress. See <http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/bdquery/z?d097:SN00881:@@@L>.

18See National Research Council, The Government Role in Civilian Technology: Building a New Alliance, Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1992, p. 29.

BOX 1-1

Commercialization Language from 1992 SBIR Reauthorization

Phase II “awards shall be made based on the scientific and technical merit and feasibility of the proposals, as evidenced by the first phase, considering, among other things, the proposal’s commercial potential, as evidenced by-

(i) the small business concern’s record of successfully commercializing SBIR or other research;

(ii) the existence of second phase funding commitments from private sector or non-SBIR funding sources;

(iii) the existence of third phase, follow-on commitments for the subject of the research; and

(iv) the presence of other indicators of the commercial potential of the idea.”

___________________________

SOURCE: P.L. 102-564-OCT. 28, 1992.

The Small Business Research and Development Enhancement Act (P.L. 102-564) reauthorized the SBIR program until September 30, 2000, and doubled the set-aside rate to 2.5 percent. The legislation also more strongly emphasized the need for commercialization of SBIR-funded technologies.19 Legislative language explicitly highlighted commercial potential as a criterion for awarding SBIR contracts and grants.

At the same time, Congress expanded the SBIR program’s purposes to “emphasize the program’s goal of increasing private sector commercialization developed through Federal research and development and to improve the federal government’s dissemination of information concerning the small business innovation, particularly with regard to woman-owned business concerns and by socially and economically disadvantaged small business concerns.”

The Small Business Reauthorization Act of 2000 (P.L. 106-554) extended the SBIR program until September 30, 2008. It also called for an NRC assessment of the program’s broader impacts, including those on employment, health, national security, and national competitiveness.20

__________________

19See R. Archibald and D. Finifter, “Evaluation of the Department of Defense Small Business Innovation Research program and the Fast Track Initiative: A balanced approach,” in National Research Council, The Small Business Innovation Research Program: An Assessment of the Department of Defense Fast Track Initiative, C.W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000, pp. 211-250.

20The current assessment is congruent with the Government Performance and Results Act (GPRA) of 1993: <http://govinfo.library.unt.edu/npr/library/misc/s20.html>. As characterized by the

THE 2011 REAUTHORIZATION

The anticipated 2008 reauthorization was delayed in large part by a disagreement between long-time program participants and their advocates in the small business community and proponents of expanded access for venture-backed firms, particularly in biotechnology where proponents argued that the standard path to commercial success includes venture funding at some point.21 Other issues were also difficult to resolve, but the conflict over participation of venture-backed companies dominated the process22 following an administrative decision to exclude these firms more systematically.23

After a much extended discussion, passage of the National Defense Act of December 2011 reauthorized the SBIR and STTR programs through FY2017. The new law maintained much of the core structure of both programs but made some important changes, which were to be implemented via the SBA’s subsequent Policy Guidance.

The eventual compromise on the venture funding issue allowed (but did not require) agencies to set aside 25 percent of SBIR funding (at NIH, DoE, and NSF) or 15 percent (at the other awarding agencies) for participation by firms benefitting from private, venture capital investment. It is too early in the implementation process to gauge the impact of this change.

Several changes to the program made through reauthorization reflected recommendations by the NRC in prior reports.24 These included the following:

- Increased award size limits

- Expanded program size

- Enhanced agency flexibility—for example to utilize Phase I awards from other agencies or to add a second Phase II

- Improved incentives for the utilization of SBIR technologies in agency acquisition programs

- Explicit requirements for better connecting prime contractors with SBIR

- Substantial emphasis on developing a more data-driven culture, which has led to several significant reforms, including the following:

__________________

Government Accountability Office (GAO), GPRA seeks to shift the focus of government decision making and accountability away from a preoccupation with the activities that are undertaken—such as grants dispensed or inspections made—to a focus on the results of those activities. See <http://www.gao.gov/new.items/gpra/gpra.htm>.

21D.C. Specht, “Recent SBIR extension debate reveals venture capital influence,” Procurement Law, 45:1, 2009.

22W.H. Schacht, “The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program: Reauthorization efforts,” Congressional Research Service, Library of Congress, 2008.

23A. Bouchie, “Increasing number of companies found ineligible for SBIR funding,” Nature Biotechnology 21(10):1121-1122, 2003.

24See Appendix B for a list of the major changes to the SBIR program resulting from the 2011 Reauthorization Act.

o adding numerous areas of expanded reporting

o extending the NRC’s evaluation

o adding further evaluation from other expert bodies, such as the Comptroller General

o tasking the SBA with creating a unified data platform

- Expanded management resources (through provisions permitting use of up to 3 percent of program funds for [defined] management purposes)

- Expanded commercialization support (through provisions providing companies with direct access to commercialization support funding and through approval of the approaches piloted in the Commercialization Pilot Program)

- Options for agencies to add flexibility by developing other pilot programs—for example, to skip Phase I or for NIH to support a new Phase 0 pilot program

The reauthorization also made changes that were not recommended in previous NRC reports. These included the following:

- Expansion of the STTR program;

- Limitations on agency flexibility—particularly in the provision of larger awards; and

- Introduction of commercialization benchmarks for companies, which must be met if companies are to remain in the program. these benchmarks are to be established by each agency

Other clauses of the legislation affect operational issues, such as the definition of specific terms (such as “Phase III”), continued and expanded evaluation by the NRC and mandated reports from the Comptroller General on combating fraud and abuse within the program, and protection of small firms’ intellectual property within the program.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH ON SBIR

Although there have been previous studies, most notably by the General Accounting Office and the Small Business Administration, they have focused on specific aspects or components of the program.25 Prior to the first round of the NRC assessment, there had been few internal assessments of

__________________

25An important step in the evaluation of the program has been to identify existing evaluations of the program. These include U.S. Government Accounting Office, Federal Research: Small Business Innovation Research Shows Success But Can Be Strengthened, Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office, 1992; and U.S. Government Accounting Office, Evaluation of Small Business Innovation Can Be Strengthened, Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office, 1999. There is also a 1999 unpublished SBA study on the commercialization of SBIR surveys Phase II awards from 1983 to 1993 among non-DoD agencies.

agency programs. At DoD, assessment work now includes a RAND corporation study in 2004.26 The academic literature on SBIR is also limited.27 Writing in the 1990s, Joshua Lerner of the Harvard Business School positively assessed the program, finding “that SBIR awardees grew significantly faster than a matched set of firms over a ten-year period.”28 To help fill this assessment gap, and to learn about a large, relatively under-evaluated program, the National Academies’ Committee for Government-Industry Partnerships for the Development of New Technologies prepared the first comprehensive discussion of the SBIR program’s history and rationale, reviewed existing research, and identified areas for further research and program improvements.29 It reported that:

- The SBIR program enjoyed strong support of parts of the federal government, as well as of the country at large.

- The size and significance of the SBIR program underscored the need for more research on its effectiveness.

- The primary emphasis on commercialization within the SBIR program required further clarification.

- Evaluation methodologies required additional work.30

In a later, more comprehensive review, the committee found that the SBIR program contributed to mission goals by funding valuable innovative projects. It also concluded that a significant number of these projects would not have been undertaken absent SBIR funding and that Fast Track encouraged the commercialization of new technologies and the entry of new firms into the program.31

The committee also found that the SBIR program affected both the development and utilization of human capital and the diffusion of technological knowledge. Case studies showed that the knowledge and human capital generated by the SBIR program have positive economic value, which

__________________

26B. Held, et al. Evaluation and Recommendations for Improvement of the Department of Defense Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Program. RAND National Defense Research Institute, Santa Monica, CA, 2006.

27Early examples of evaluations of the SBIR program include S. Myers, R. L. Stern, and M. L. Rorke, A Study of the Small Business Innovation Research Program, Lake Forest, IL: Mohawk Research Corporation, 1983; and Price Waterhouse, Survey of Small High-tech Businesses Shows Federal SBIR Awards Spurring Job Growth, Commercial Sales, Washington, DC: Small Business High Technology Institute, 1985.

28See J. Lerner, “The Government as Venture Capitalist: The Long-Run Effects of the SBIR Program,” op. cit.

29See National Research Council, The Small Business Innovation Research Program: Challenges and Opportunities, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1999.

30National Research Council, An Assessment of the DoD SBIR Fast Track Initiative, C.W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000. See Chapter III: Recommendations and Findings, p. 32.

31Ibid, p. 33.

spills over into other firms through the movement of people and ideas. Furthermore, by acting as a “certifier” of promising new technologies, SBIR awards encourage further private-sector investment in an award-winning firm’s technology.32

THE NRC ROUND ONE STUDY OF SBIR

Drawing on these NRC findings and recommendations, the 2000 SBIR reauthorization mandated that the National Research Council complete a comprehensive assessment of the SBIR program. This assessment was conducted in three steps. During the first step, the Committee developed a research methodology,33 which was approved by an independent National Academies panel of experts. The committee gathered information about the program by engaging in discussion with officials at the relevant federal agencies and by inviting those officials to describe program operations, challenges, and accomplishments at two major conferences. These conferences highlighted the important differences in agency goals, practices, and evaluations. They also served to describe the evaluation challenges that arise from the diversity in program objectives and practices.34

The research methodology was implemented during the second step. The Committee deployed multiple survey instruments, and its researchers conducted case studies of a wide variety of SBIR firms. The Committee then evaluated the results and developed the findings and recommendations presented in this report for improving the effectiveness of the SBIR program.

During the third step, the committee reported on the program through a series of publications in 2008-2010: five individual volumes on the five major funding agencies and an additional overview volume entitled An Assessment of the SBIR Program.35 Together, these reports provided the first detailed and comprehensive review of the SBIR program and, as noted above, became an important input into SBIR reauthorization prior to December 2011. (See Box 1-2.)

THE CURRENT, SECOND-ROUND STUDY: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

The first set of NRC reports on the SBIR program established that, overall, the program is “sound in concept and effective in practice.”36 Further, in

__________________

32Ibid, p. 33.

33National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2004.

34Adapted from National Research Council, SBIR: Program Diversity and Assessment Challenges, op. cit.

35National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2008.

36Ibid, p. 54.

its review of the DoD SBIR program, the NRC concluded that “[t]he SBIR program at the Department of Defense is meeting the legislative and mission-related objectives of the program.”37 The current study now seeks to understand how the DoD SBIR program could work better.

Along with the current volume, a number of NRC workshops and other publications will fully address this statement of task. The committee convened workshops on the participation of women and minorities in SBIR/STTR (February 2013) and on the evolving role of university participation in the program (February 2014). As a part of the broader task before the committee, future workshops will focus on the role of state programs to encourage participation in SBIR and on agency commercialization programs.

The current volume is focused on updating the committee’s 2009 assessment of the DoD SBIR program, by updating data, providing new descriptions of recent program and developments, providing fresh company case studies. This volume, in particular, focuses on the efforts made at DoD in recent years to improve the SBIR program. Guided by this Statement of Task, the committee has sought answers to questions such as the following:

- Are there initiatives and programs within DoD that have made a significant difference to outcomes and in particular to agency take-up of SBIR-funded technologies?

- Can they be replicated and expanded?

- What are the main barriers to meeting Congressional objectives more fully?

- What program adjustments would better support commercialization?

- Are there tools that would expand utilization by woman and minority-owned firms and participation by female and minority principal investigators?

- Can links with universities be improved?

- Why do some firms simply drop out of the program?

- Are there aspects of the program that make it less attractive? Could they be addressed?

- What can be done to expand access in underserved states while maintaining the competitive character of the program?

- Can the program generate better data on both process and outcomes and use those data to fine-tune program management?

______________________

37National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program at the Department of Defense, p.23, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2007.

BOX 1-2

The National Research Council’s First-Round Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Program

Mandated by Congress in the 2000 reauthorization of the SBIR program, the National Research Council’s (NRC) first-round SBIR assessment reviewed the SBIR programs at the Department of Defense, National Institutes of Health, NASA, the Department of Energy, and the National Science Foundation. In addition to the release of reports focused on the SBIR program at each of these agencies and a program methodology report that guided the NRC committee’s review, the study resulted in a summary of a symposium focused on the diversity of the program and challenge of its assessment, a summary of a symposium focused on the challenges in commercializing SBIR-funded technologies, and two additional reports on special topics in addition to the committee’s summary report, An Assessment of the SBIR Program. In all, eleven study reportsa were published:

- An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology (2004)

- SBIR—Program Diversity and Assessment Challenges: Report of a Symposium (2004)

- SBIR and the Phase III Challenge of Commercialization: Report of a · Symposium (2007)

- An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the National Science Foundation (2007)

- An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the Department of Defense (2009)

- An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the Department of Energy (2008)

- An Assessment of the SBIR Program (2008)

- An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (2009)

- An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the National Institutes of Health (2009)

- Venture Funding and the NIH SBIR Program (2009)

- Revisiting the Department of Defense SBIR Fast Track Initiative (2009)

______________________

aNational Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2004; National Research Council, SBIR—Program Diversity and Assessment Challenges: Report of a Symposium, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2004; National Research Council, SBIR and the Phase III Challenge of Commercialization: Report of a Symposium, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2007; National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the National Science Foundation, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2007; National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the Department of Defense, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The

National Academies Press, 2009; National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the Department of Energy, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2008; National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2008; National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009; National Research Council, An Assessment of the SBIR Program at the National Institutes of Health, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009; National Research Council, Venture Funding and the NIH SBIR Program, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009; and National Research Council, Revisiting the Department of Defense SBIR Fast Track Initiative, Charles W. Wessner, ed., Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2009.

Study Methodology

It is always useful when assessing government programs to identify comparable programs for appropriate benchmarking. However, comparable programs do not really exist in the United States, and those in other countries operate in such different ways that their relevance is limited. The SBIR/STTR programs are relatively unique in terms of scale and mission focus. Appendix A of this report provides a detailed review of the methods used for this assessment.

Assessing the SBIR program at DoD is challenging for other reasons as well. “The SBIR program” is in fact a multiplicity of agency-specific programs, some of which—especially at DoD—are managed very differently by different components even within the same department. Navy, Air Force, and Army and in some cases smaller components as well have different operational structures, metrics, and support systems, as do some of the other DoD components. In this report the committee is careful to distinguish between aspects of the program that are component specific and those that can be discussed more widely.

Focus on Legislative Objectives

It is important to note at the outset that this volume—and this study—does not seek to provide a comprehensive review of the value of the SBIR program, in particular measured against other possible alternative uses of Federal funding. This is beyond our scope. Our work is focused on assessing the extent to which the SBIR program at DoD has met the Congressional objectives set for the program, to determine in particular whether recent initiatives have improved program outcomes, and to provide recommendations for improving the program further.38

___________________________________

38These limited objectives are consistent with the methodology developed by the committee. See National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology, op. cit.

BOX 1-3

Statement of Task

In accordance with H.R. 5667, Sec. 108, enacted in Public Law 106-554, as amended by H.R. 1540, Sec. 5137, enacted in Public Law 112-81, the National Research Council is to review the Small Business Innovation Research and Small Business Technology Transfer (SBIR/STTR) programs at the Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Department of Energy, and the National Science Foundation. Building on the outcomes from the Phase I study, this second study is to examine both topics of general policy interest that emerged during the first-phase study and topics of specific interest to individual agencies.a

Drawing on the methodology developed in the previous study, an ad hoc committee will issue a revised survey, revisit case studies, and develop additional cases, thereby providing a second snapshot to measure the program’s progress against its legislative goals. The committee will prepare one consensus report on the SBIR program at each of the five agencies, providing a second review of the operation of the program, analyzing new topics, and identifying accomplishments, emerging challenges, and possible policy solutions. The committee will prepare an additional consensus report focused on the STTR Program at all five agencies. The agency reports will include agency-specific and program-wide findings on the SBIR and STTR programs to submit to the contracting agencies and the Congress.

Although each agency report will be tailored to the needs of that agency, all reports will, where appropriate:

- Review institutional initiatives and structural elements contributing to programmatic success, including gap funding mechanisms such as applying Phase II-plus awards more broadly to address agency needs and operations and streamlining the application process.

- Explore methods to encourage the participation of minorities and women in SBIR and STTR.

- Identify best practice in university-industry partnering and synergies with the two programs.

- Document the role of complementary state and federal programs.

- Assess the efficacy of post-award commercialization programs.

In partial fulfillment of this Statement of Task, this volume presents the committee’s second review of the operation of the SBIR program at the Department of Defense.

__________________

aThe Phase I study refers to the NRC Round One assessments discussed above.

Thus, as in the first-round study, the objective of this second round study is “not to consider if SBIR should exist or not”—Congress has already decided affirmatively on this question, most recently in the 2011 reauthorization of the program.39 “Rather, the NRC Committee conducting this study is charged with “providing assessmentǦbased findings of the benefits and costs of SBIR … to improve public understanding of the program, as well as recommendations to improve the program’s effectiveness.” As with the first-round, this study “will not seek to compare the value of one area with other areas; this task is the prerogative of the Congress and the Administration acting through the agencies. Instead, the study is concerned with the effective review of each area.” 40

Defining Commercialization

Commercialization offers practical and definitional challenges. As described in Chapter 3, several different definitions of commercialization can be used to discuss the SBIR program. The committee concluded that it is important to use more than one simple definition. For example, a simple measure of the percentage of funded projects that reach the marketplace is not the only measure of commercial success.

In the private sector, commercial success over the long term requires profitability. However, in the short term, commercialization can involve many different aspects of commercial activity, from product rollout to licensing to patenting to acquisition. Even during new product rollout, companies often do not generate immediate profits. In this report the committee uses multiple metrics to address the question of commercialization (see Chapter 3).

Quantitative Assessment Methods

More practically, several issues relate to the application of quantitative assessment methods, including decisions about which kinds of program participants should be targeted for survey deployment, the number of responses that are appropriate, selection bias, nonresponse bias, the design and implementation of survey questionnaires, and the level of statistical evidence required for drawing conclusions in this case. These and other issues were discussed at a NRC workshop and published in a 2004 report.41 Also prepared was a peer-reviewed report on study methodology, which provided the baseline for the initial study and for follow-on studies—such as this one. 42

__________________

39National Defense Authorization Act of 2012 (NDAA) HR.1540, Title LI.

40National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology, op. cit.

41NRC, The Small Business Innovation Research Program: Program Diversity and Assessment Challenges, National Academies Press, Washington DC, 2004.

42National Research Council, An Assessment of the Small Business Innovation Research Program: Project Methodology, op. cit.

Survey Development

For the current study, a new survey of SBIR recipients was developed and deployed. The survey43 was based closely on previous surveys, particularly one deployed by the NRC in 2005, but nonetheless included significant improvements. The survey delved more deeply into the demographics of the program. It addressed in detail the role of agency liaisons who manage the contract operationally and hence link individual projects at companies to DoD. And it provided unique opportunities to collect qualitative views on the program and recommendations for improvement from recipients. The survey generated more than 1,000 responses from DoD award recipients and provided an important pillar to the research conducted for this volume. Appendix A provides a detailed discussion of the issues related to quantitative methodologies, as well as a review of potential biases. The Committee fully recognizes that there are significant limitations on the conclusions that can be drawn from this assessment, and this recognition is reflected in their findings and recommendations (Chapter 7). However, the Committee also concludes that drawing on quantitative analysis is a crucial component of the overall study, given the need to identify and assess outcomes that are to be found only at the level of individual projects and participating companies.

A Complement of Approaches

Partly because of these limitations, the 2004 methodology report stressed the importance of utilizing a complement of approaches, which has been adopted here. Although quantitative assessment represents the bedrock of the committee’s research and provides insights and evidence that could not be generated through any other modality, it is, in and of itself, not sufficient to address the multiple questions posed in this analysis. Consequently, the committee undertook a series of additional activities:

- Case studies. The committee conducted in-depth case studies of 20 DoD SBIR recipients. These companies were geographically and demographically diverse, funded by several different components at DoD, and at different stages of the company lifecycle. Lessons from the case studies are described in Chapter 5, and the cases themselves are included as Appendix F.

- Workshops. The committee conducted workshops, including workshops to discuss the participation of women and minorities in

________________

43The survey carried out as part of this study was administered in 2011, and the survey completed as part of the first-round NRC assessment of SBIR was administered in 2005. In this volume all NRC survey references are to the 2011 survey unless noted otherwise.

-

SBIR and the role of universities in SBIR,44 to allow stakeholders, agency staff, and academic experts to provide insights into program operations, as well as to identify issues that need to be addressed.

- Analysis of agency data. As appropriate, the committee analyzed and included data from DoD or DoD components that cover various aspects of SBIR activities.

- Open-ended responses from SBIR recipients. For the first time, the committee collected textual responses in the survey. More than 700 recipients provided narrative comments. These comments are addressed in chapter 5.

- Agency consultations. The committee engaged in discussions with agency staff at several of the components about the operation of their program and the challenges they face.

- Literature review. Since the start of NRC research in this area, a number of papers have been published addressing various aspects of the SBIR program. In addition, other organizations—such as GAO—have reviewed specific parts of the SBIR program. The committee incorporated references to their work, where useful, into its analysis.

Data Sources and Limitations

Multiple research modalities are especially important because limitations still exist in the data collected for the SBIR program. That said, the DoD SBIR program has been a leader in collecting outcomes data from firms through a pioneering initiative called the Company Commercialization Record (CCR). These data provide important insights. Nonetheless, there are real gaps, especially in relation to the take-up of SBIR-funded technologies by prime contractors (“primes”). The primes account for about one-third to one-half of acquisition spending at DoD, depending on the component and Program Executive Office (PEO). Tracking the primes’ use of SBIR technologies is therefore an important element in understanding program impact.

The Federal Procurement Data System (FPDS) provides useful data, but because it relies on individual contract officers to enter the data, not all SBIR technologies are tracked correctly or consistently. In addition, the downstream reach of FPDS is very limited: the system may record the first Phase III contract after a Phase II (i.e., the first commercial contract from the

__________________

44Workshops convened by the committee as part of the overall analysis include NASA Small Business Innovation Research Program Assessment: Second Phase Analysis, January 28, 2010; Early-stage Capital in the United States: Moving Research Across the Valley of Death and the Role of SBIR, April 16, 2010; Early-Stage Capital for Innovation--SBIR: Beyond Phase II, January 27, 2011; NASA's SBIR Community: Opportunities and Challenges, June 21, 2011; Innovation, Diversity, and Success in the SBIR/STTR Programs, February 7, 2013; and Commercializing University Research: The Role of SBIR and STTR, February 5, 2014. Each of these workshops was held in Washington, DC.

technology), but it may not fully track subsequent commercial contracts—some of which are likely to be much larger over time.

Cooperation with DoD Components

The Committee in general received substantial cooperation from DoD and the components. Numerous discussions took place between agency staff and the NRC research team, and DoD provided a considerable amount of data, papers, and presentations. DoD SBIR managers also participated extensively in various SBIR workshops at the Academy. Unfortunately, the Army SBIR office declined to participate in any of these activities, despite repeated invitations.

In short, within the limitations described, the study utilizes a complement of tools to ensure that a full spectrum of perspectives and expertise is reflected in the findings and recommendations. Appendix A provides an overview of the methodological approaches, data sources, and survey tools used in this study.

ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT

The Committee’s analysis and conclusions are organized as follows. Chapter 2 reviews DoD data concerning applications and awards to the program, drawing out differences by component, demographic, geography, industry sector, and previous experience with the program. Chapter 3 describes the study methodology and provides a quantitative assessment of the program, drawing on the NRC survey but also on other sources of quantitative data. Chapter 4 describes and analyzes in some detail the wide range of agency and component initiatives that have been developed and implemented over the past 8 to 10 years, largely aimed at improving program outcomes. Chapter 5 draws on company case studies and on the textual responses from survey respondents to provide a qualitative picture of program operations, issues, and possible solutions. Chapter 6 provides a review of program operations, examining the role of agency liaison offices in some detail, issues related to auditing and contracts, and other issues related to program management, as well as efforts to address the Congressional mandate to foster the participation of women and minorities. Chapter 7 provides the findings and recommendations from the study.

The report’s appendices provide additional information. Appendix A sets out an overview of the methodological approaches, data sources, and survey tools used in this assessment. Appendix B describes key changes to the SBIR program from the 2011 Reauthorization. Appendix C lists universities involved in the DoD SBIR awards. Appendix D provides a list of acronyms used. Appendix E reproduces the 2011 survey instrument. Appendix F presents the case study of selected DoD SBIR firms. Appendix G describes the committee’s attempts to find a suitable comparison group for the survey data, and, finally, Appendix H provides a list of references.