The workshop explored several ways to overcome the barriers to wider implementation of evidence-based preventive interventions for children, including developing metrics, standards, and guidelines for implementation; integrating organizational and professional silos; and providing more funding—and support for evidence-based interventions (EBIs) and their implementation.

DEVELOPING METRICS, STANDARDS, AND GUIDELINES

Several presenters and participants in breakout groups emphasized the importance of developing the appropriate metrics, standards, and guidelines for desired outcomes to ensure preventive EBIs are appropriately applied and to help make the business case for such interventions.

Appropriate Goals, Measures, and Outcomes

Bryan Samuels of Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago pointed out that a major flaw in the Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA) of 1997 was its lack of appropriate goals and outcome measures. The main principles of that law, as Samuels outlined them, were

- Safety of children is the paramount concern that must guide all child welfare services.

- Foster care is a temporary setting and not a place for children to grow up.

- Permanency planning efforts should begin as soon as a child enters the child welfare system.

- The child welfare system must focus on results and accountability.

But the results the system focused on were not appropriate, according to Samuels. Because of this reform in child welfare, there was a significant drop in the overall size of the foster care population, which has been touted as showing that the law was successful. That drop was mainly due to a combination of adoptions and keeping more children at home. But “the legislation didn’t speak to the social and emotional well-being of a child or to the EBIs needed to achieve that,” Samuels pointed out. “The operationalization of that policy didn’t require that children actually be served effectively in order to get them out of the [foster care] system.”

Samuels noted that conformity with federal child welfare requirements (e.g., maltreatment investigations, removal of children from biological home, caseworker visits, training and monitoring of foster parents) does not necessarily improve clinical outcomes for children. He added that many children in the out-of-home care system have clinical-level needs due to social and emotional issues, and many of these children also have physical health conditions. “What happens to children before they come into the system has to be connected with what happens to them when they are in the system,” Samuels said. But according to Samuels, most state Medicaid agencies will not pay for the complex care required to treat children who have experienced maltreatment prior to foster care. In most states, children are required to have a diagnosis of mental illness before Medicaid will pay for behavioral health interventions.

Samuels stressed that state agencies tend to purchase or reimburse services but not the outcomes EBIs are designed to achieve. “They know how to purchase a unit of service, but purchasing a unit of outcome is a significantly different challenge, and building the procurement capacity to do that is critical to succeeding,” Samuels said. Similarly, other participants noted that many health care performance measures are for processes followed and not outcomes achieved in the target population. Kelly Kelleher of Ohio State University and Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, suggested there be standard outcome measures for children that can guide what accountable care organizations have to do for children and that Medicaid directors would accept as valid. Many proposed outcome measures and accountability measures for adults exist, but no such standards for accountable care currently address pediatrics.

Samuels pointed out that there has been limited interest or energy focused on how to standardize outcome measurements. Common understanding about what successes are, and standardized outcomes to measure those successes, will enable child welfare agencies across all states to meet

their obligations, Samuels said. Bruns added, “We need more guidance that would help us measure similar things that matter across states.” He noted that the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS), a tool used by the private insurance industry as well as by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services to assess performance on measures of health care, currently includes only a few measures of behavioral health in children. Bruns went on to state, “We’re not asking states to report consistently even about penetration rates and what kinds of services are being delivered, so we have no basis for understanding what strategies seem to be working. Even just that kind of consistency and expectations of measurement around real-world things we’re trying to achieve would be a huge step.”

Richard Frank, Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), suggested that there be broad measures to indicate whether a program is working, as well as a tiered approach to quality measurement such that if a simple indicator suggests possible failure, there would then be a different level of scrutiny requiring collecting more data. If that second level of scrutiny also indicated failure, then the system would undergo a detailed audit.

Members of the health care breakout group discussed the importance of measurement and having appropriate metrics at the planning and implementation stages for EBIs, including metrics that can provide feedback on how well a program is being implemented. Several group participants suggested that the outcomes that are measured within a system be developmentally appropriate at different stages of a child’s life. Members of the group also thought it would be beneficial if the data collected on outcomes fit the needs of stakeholders, such as state Medicaid directors or managed care organizations, and that metrics development start by focusing on outcomes shared over the several sectors overseeing the welfare of children.

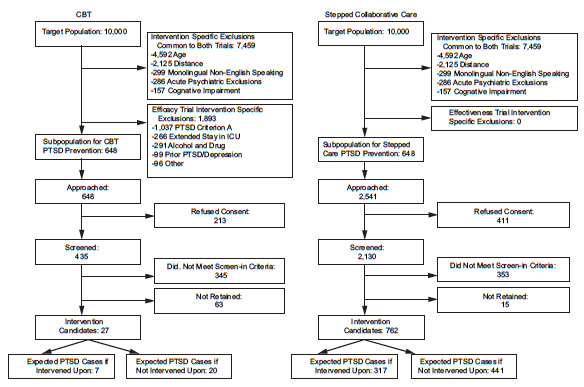

Another measurement issue that needs to be addressed is that often researchers and state agencies use inappropriate metrics when assessing the value of an EBI because they rely on effect size instead of reach, Bruns pointed out. The population impact of an intervention depends on two factors: what proportion of the full population at risk receives the intervention (reach) and how large a reduction in risk (effect size) occurs among those who receive it (Zatzick et al., 2009). Some interventions may have large effect sizes but a small reach, whereas other interventions with a smaller effect size but a larger reach can have a greater impact on the population of interest.

Bruns suggested combining measurements of the target population, effect size, and reach to assess the overall population impact of a prevention intervention. He discussed one study of two preventive interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Although the target population was the same when each intervention was applied, one had a much bigger

effect size than the other. But the latter intervention, even though it had an effect size of only 10 percent, was able to prevent 10 times more cases of PTSD because it did not have as many barriers to uptake and retention, including cost factors and exclusion criteria (Zatzick et al., 2009) (see Figure 3-1). “We should replace effect size as the metric we’re looking for in our programs with capacity to reach as many individuals as possible,” Bruns said. Charles Collins of the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) concurred and suggested considering the actual reach versus the potential reach of an EBI, and if there is insufficient reach, consider discontinuing the program and applying a different one.

There is a lack of specific standardized quality metrics for behavioral health that can be used in multiple sectors, several participants pointed out, as well as metrics for effective parenting. But members in the schools breakout group noted that there are a number of well-accepted measures for children’s behavior and academic achievement that could be more widely applied. “If you added psychological well-being to those measures, you would have a pretty good profile that would be useful for juvenile justice or for any other enterprise,” Sheppard Kellam of Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health said. He suggested these metrics could serve as proximal measures for employment rates and other outcomes that occur later in young adulthood.

Members of the health care breakout group also concurred with the suggestion of some of the presenters that better metrics need to be developed in order to make the business case for preventive interventions, given that often prevention has long-term gains. Participants in the group suggested considering proximal measures that will predict the long-term health measures that will follow, and that all measures used be specific to context, publicly available, understandable and easy to use, actionable, and developmentally appropriate for the stage of life one is trying to optimize.

Some child welfare and juvenile/family justice breakout group members also emphasized the importance of having metrics that can reveal the return on investment made from a prevention EBI. Palinkas noted that in the adult realm there are economic measures such as quality-adjusted life years, which is a component of the Quality of Well-Being Scale, but that there is no comparable scale for prevention in children and youths, and he suggested focusing on developing one. He added that the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which funds the community youth development study, has shown that there is a return of $5 for every $1 invested in prevention and that a similar calculation could be followed to figure return on investment for other prevention programs.

Members of the health care breakout group suggested there could be greater use of existing measures, such as those used in the National Insti-

FIGURE 3-1 Program reach vs. effect size.

NOTES: Projected cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and stepped collaborative care flow diagrams specifying target populations

for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) prevention. ICU = intensive care unit.

SOURCE: Zatzick et al., 2009, reprinted with permission.

tutes of Health (NIH) Toolbox, which is a multidimensional set of brief measures assessing cognitive, emotional, motor, and sensory function in individuals age 3 to 85 and that meets the need for a standard set of measures that can be used as a “common currency” across diverse study designs and settings (NIH Toolbox, 2014). Although these measures have been deployed in health settings and to some degree in mental health settings, they have not necessarily been used as often in juvenile justice, foster care, and child welfare, noted David Chambers, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). “Is there a way that, in a cross-sector fashion, we can try to bridge these different measures of health and mental health in these other settings?” he asked.

Practice Recommendations

Along with metrics and standards, some participants suggested there be more official sanctioning of prevention EBIs so they are more readily adopted and funded. A well-respected organization that provides recommendations regarding preventive services to be provided in primary care settings is the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), which is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Alex Kemper of Duke University School of Medicine, who is a member of the USPSTF, reported on how the Task Force makes its recommendations and how those recommendations are graded according to evidence quality (see Box 3-1).

Kemper noted that the USPSTF has made few recommendations related to child development and behavior. Examples of those that have been made include B recommendations for screening for a major depressive disorder in adolescents when systems are in place for follow-up, and for interventions to prevent the initiation of smoking and tobacco use in this population. The Task Force concluded that thus far there is insufficient evidence (see table in Box 3-1) to make recommendations regarding suicide risk, alcohol misuse, or illicit or nonmedical drug use in adolescents, nor is there sufficient evidence to make recommendations for screening for major depressive disorders in children age 7 to 11 years. The USPSTF is currently reviewing studies on autism spectrum disorder and is updating the insufficient evidence assessment it previously made related to speech and language delay for children 5 years old and younger.

In response to a question from a participant, Kemper noted that it is possible for the USPSTF to evaluate the evidence and make a recommendation on the value of various types of counseling designed for primary prevention. The Task Force would evaluate the harms and benefits of providing the counseling and whether the counseling leads to the intended outcome.

Mary Jane Rotheram-Borus of the University of California, Los Angeles, asked if the USPSTF would consider evaluating parenting practices. “How

can we get something like parenting classes linked to outcomes?” she asked, noting the abundance of data that links poor parenting practices to a number of high-cost negative outcomes, such as a lack of adherence to asthma prevention measures. Kemper responded that parenting classes can affect a number of different outcomes, but the USPSTF only evaluates primary prevention interventions applied to the population at large for a targeted condition in controlled trials (see Box 3-1). “It just doesn’t fit in there exactly right—you have to think about whether it fits into the primary prevention paradigm or is it really secondary or tertiary prevention,” he said. He added that the latter would be more appropriately evaluated by another organization that provides guidelines for pediatric care, such as the American Academy of Pediatrics, including Bright Futures, which is a national health promotion and disease prevention initiative that addresses children’s health needs in the context of family and community, and CDC’s community guide, which offers recommendations for community-level interventions for children.

Jeff Sugar of the University of Southern California asked if the USPSTF has evaluated interventions for maltreatment. Kemper responded that this is a topic that the Task Force would evaluate and make recommendations on, although it would have to consider assessing whether all children ought to be screened for child maltreatment.

A theme question at the workshop was how to integrate silos, including mental, behavioral, public health, and primary care, as well as how to integrate the various government agencies that oversee the domains in which children are cared for, such as public schools, Medicaid, child welfare, and juvenile justice agencies. Better communication and sharing of data and objectives also could occur in the various child-focused professions such as child psychiatry and psychology, school social work, teaching, nursing, and counseling.

Kellam suggested that various sectors and disciplines could integrate their services to achieve the common goal of having children reach their full potential. Other participants concurred and added that there be incentives so that goal is met. “The boundaries we have created are suboptimal for dealing with the world as it is, and we need to think about the world as it could be,” Brown emphasized.

Public Health and Primary Care

Advocating for more merging of public health with primary care, David Hawkins of the University of Washington School of Social Work

BOX 3-1

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Grading Process

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is an independent body of 16 nonfederal experts in prevention and evidence-based medicine that have expertise across the broad swath of primary care, including family medicine, internal medicine, nursing, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, and behavioral medicine. The Task Force’s volunteer members, who include both practicing and academic clinicians, serve 4-year terms and are appointed by the director of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. This agency provides administrative, scientific, and technical dissemination support for the Task Force.

The USPSTF makes recommendations on clinical preventive services to primary care clinicians. The USPSTF’s scope for clinical preventive services includes screening tests, counseling, and preventive medications. Recommended services are offered in or referred only from the primary care setting, and the USPSTF recommendations apply to adults and children with no signs or symptoms of the conditions the recommendations aim to prevent.

Anyone can nominate a topic for the USPSTF to consider via its website (http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org, accessed October 24, 2014). The public may suggest a new preventive service topic or recommend the Task Force reconsider an existing topic owing to new evidence or changes in the public health burden of the condition a prevention intervention targets. Topic nominations are accepted year-round and are considered by the USPSTF at its three annual meetings. The public is invited to comment on the USPSTF research plan for the service the Task Force is reviewing, as well as on its evidence report and recommendation statement, before each is finalized (http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/methods-and-processes, accessed October 24, 2014).

The USPSTF makes its recommendations after consulting with experts and conducting a rigorous review of peer-reviewed published studies on the intervention. This review assesses the benefits and harms of all the outcomes of applying the intervention for specific populations, which are broken down by age and sex. Before making its recommendations, the Task Force assigns a certainty value to its assessment of the net benefit of a preventive service, based on the number, quality, or consistency of studies and their applicability to practice.

All of this information is used to grade its recommendations, with A and B grades given to interventions in which the net benefit is substantial or moderately substantial and for which there is good certainty. C recommendations are given when the benefits and the harms are balanced and there is moderate certainty that the overall net benefit is small. Such recommendations require discussing the intervention with patients and soliciting their input as to whether they wish to pursue it, Kemper noted, unlike A or B recommendations, which should be routinely provided. The Task Force gives D recommendations if it recommends against the service because the potential harms outweigh the potential benefits.

When the current evidence is insufficient for the Task Force to make a judgment on an intervention’s benefits or risks, the Task Force provides what is known as an I statement. “I statements are really important because we need to know where the gaps are in our scientific judgment. The NIH looks at these I state-

ments when it prioritizes what sorts of research need to be done,” Kemper said. He ended his presentation by stressing that the Task Force does not consider the economics of the recommendations it makes and their cost-effectiveness, but rather whether a particular recommendation is likely to lead to benefit for the population of interest.

| Grade | Definition |

| A | The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is substantial. |

| B | The USPSTF recommends the service. There is high certainty that the net benefit is moderate or there is moderate certainty that the net benefit is moderate to substantial. |

| C | The USPSTF recommends selectively offering or providing this service to individual patients based on professional judgment and patient preferences. There is at least moderate certainty that the net benefit is small. |

| D | The USPSTF recommends against the service. There is moderate or high certainty that the service has no net benefit or that the harms outweigh the benefits. |

| I Statement | The USPSTF concludes that the current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of the service. Evidence is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting, and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. |

High Certainty: Evidence includes consistent results from well-designed, well-conducted studies in representative primary care populations, using health outcomes. Conclusion unlikely to be strongly affected by the results of future studies.

Moderate Certainty: Evidence is insufficient to determine the effects on health outcomes, but confidence in the estimate is constrained by limitations in the research. As more information becomes available, magnitude or direction of the observed effect could change, and change may be large enough to alter the conclusion.

Low Certainty: Available evidence is insufficient to assess effects on health outcomes.

SOURCE: USPSTF, 2014.

noted that it is difficult to get uptake of universal preventive interventions, such as those given to parents of adolescents, when these EBIs are offered in schools and other community settings. He suggested that if primary care physicians recommended such interventions to the parents of all their pediatric patients once these children approach adolescence, there may be greater uptake of these interventions.

But as Frank responded, reimbursement and referral systems are driven by a medical, insurance-based model that is not a public health model. He noted that does not preclude funding public health organizations that can bridge the gap and reach out to pediatricians and family doctors so they are more likely to refer such services to their patients. He added that the health homes for Medicaid beneficiaries being funded by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) are currently experimenting with expanding into the public health arena by connecting adults and children with multiple chronic conditions to housing, nutritional support, and other types of social services. However, Sugar expressed caution over using the primary care setting to deliver, rather than refer out, social and emotional training and stressed that “if you treat kids in a primary care setting, you are going to get a very medicalized treatment for social problems, which hasn’t worked well.”

Members of the child welfare and juvenile/family justice breakout group noted that schools and primary care settings are ideally positioned to engage in primary prevention or universal prevention activities, including screening and assessment programs, and that once children enter the child welfare or juvenile justice system, there is a greater need for more targeted and intensive types of prevention programs. Finding funding for such prevention efforts can be problematic, however. One participant noted that because preventive services are often offered in school or community settings, the savings they foster in primary care is not returned to preventive care programs, like it is in totally accountable care organizations. “Prevention is often in places that are outside of where this pay for performance may actually be effective,” he noted.

Director Frances Harding of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA’s) Center for Substance Abuse Prevention noted that SAMHSA now has an internal mission to bring behavioral health into primary care. She also pointed out that in terms of funding, some prevention programs fit nicely into primary care while others probably never will, even though “they could be a huge asset to the community. If we don’t address some of the issues of substance abuse and mental health disorders, we will not have the healthy society we are striving for.”

Kelleher emphasized in his presentation that many costs and problems in the health care system relate to undetected or untreated behavioral problems in families and children; moreover, “without integrated behav-

ioral health and primary care, we are not going to make a lot of progress.” But such integration is not just a matter of integrating budgets. He also called for decreased use of behavioral health carve outs in managed care, national telemedicine standards to ease the electronic transmission of medical information from one system to another, and integration of foster care and juvenile justice health services and data so there can be cross-tracking and monitoring of resources, expenses, and outcomes of children in these systems with the health care records.

Integration of Data Systems for Children

Many participants in the breakout groups stated support to the suggestion of harmonizing and exchanging electronic data and other information between the various domains in which a child is involved, including schools. Kellam noted that there are 14 different systems of information regarding children, and few actually relate to local communities over time. He suggested that having an information system that combines health care and educational data on children would enable better integration of services provided at the community level. “There’s about to be a whole new health system that’s totally unrelated to the developmental information that’s in the school information system, and the laws do not allow people in these two sectors to exchange information. Now that we’re developing ACA, we need to take this opportunity to shape a single information system that tracks kids and their needs over time across academic, behavioral, and health issues. We may never have this opportunity again,” Kellam emphasized.

Palinkas noted that there are existing models for how technology can aid the flow of information about children across sectors, such as CDC’s linked network of service. However, he also mentioned that the legal system has not caught up with the technology such that it is difficult to forge data-sharing agreements between different organizations. There may need to be state-by-state negotiation of data-sharing agreements or some other legal strategy to enable more data exchange across sectors. “This is something that we need to begin working on,” Palinkas said.

Participants in the child welfare and juvenile/family justice breakout group also suggested there be greater face-to-face communications of the appropriate personnel in these sectors, such as between a child welfare worker and probation officer or school psychologist. This communication could be a job requirement, such that child welfare workers are expected to interact with representatives from other systems. But that would require reimbursement structures that support these interactions, “because many times a child welfare worker does not get paid for calling up a probation officer and trying to coordinate services,” Palinkas said. Integration of in-

formation across sectors can also be impeded by a lack of a common framework or language, Kellam noted. “Do we use the psychologist’s language or the educator’s?” he asked. He suggested developing a common language for professionals that care for children.

A participant in the schools breakout group added that it would be helpful if, instead of juvenile justice agencies being solely responsible for the education of their incarcerated clients, schools share that responsibility “because the schools are going to do a better job of it.”

Integration of Disciplines

In addition to integrating sectors, members in the schools breakout group suggested there be more integration of disciplines. Participants in the group suggested training teachers and school nurses in behavior management and in child mental health and prevention programs. Child psychiatrists and school psychologists should also receive training in such areas, as well as experience in the classroom setting, Kellam said. He noted that although one of the largest health care expenditures is stimulant medication for children prescribed by psychiatrists as a way to improve school performance, child psychiatric residents often are not required to operate within schools and experience the classroom setting. He added that teachers often receive little education in child development in college or as training in classroom behavior management. The national accreditation of the schools of education does not require such training of the teachers they certify, he said.

School nurses could also be doing more than attending to sick or injured children in the schools, Kellam added. Such personnel could be screening children and families for mental and physical health issues or providing prevention programs if they were trained to do so. One participant in the schools breakout group pointed out that there is an ongoing initiative to use nurses to provide education and interventions aimed at reducing substance use in schools, and the early data from this program look promising. Teacher in-services that show how social and emotional interventions affect the developmental course of children and their educational achievement might also be useful, another participant noted.

Integration of Research with Practice

Participants in the child welfare and juvenile/family justice breakout groups suggested there be more partnership development that would link academic researchers or government officials to those in the field. Palinkas noted that programs such as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) and NIMH in general have requirements for how re-

search–practice partnerships should be developed. A major challenge in any partnership with the community is the issue of trust and long-term commitment required to build that trust. This commitment can be contrary to academic pressures to “publish or perish,” which make it difficult to take the time to build that trust, Palinkas pointed out. But qualitative methods in which participants are interviewed about what their needs are and which programs would be useful to them offer a way of building trust in the community and engaging it to a greater extent than “simply handing out surveys and questionnaires or running randomized controlled trials,” Palinkas said.

Members of the schools breakout group also concurred with the need for joint research projects on substance abuse or some other topic with practical outcomes and applications in the school community. This research would require public health or academic researchers to partner with school personnel or other people “who have their boots on the ground from all disciplines to meld that basic science and community intervention together,” one of the breakout participants emphasized. Participants in the schools group also suggested forging partnerships between schools and the communities they are in so different agencies and programs work together at the local level around common child-centered goals.

Integration of Agencies

Social welfare and juvenile/family justice breakout group members pointed out that in order to have federal and local partnerships for youth prevention programs, there needs to be an alignment of Medicaid demonstration authority with the waiver programs such as Title IV-E that are available for child welfare and juvenile justice. Currently, there is misalignment such that youth in the juvenile justice system are ineligible for Medicaid under certain conditions, such as when they are incarcerated for extended durations in federal prisons or jails. Participants in this breakout group also suggested that performance pilots could be a way to bring different funding streams together for research–practice partnerships for disconnected youth.

Chambers noted that a current barrier to funding prevention programs is the lack of integration and coordination between funding sources. A grant program offered by the Department of Education for schools is not tied to one for primary care or child welfare settings, for example. “This perpetuates the disconnection and duplication of effort, and you end up with much more expensive and less effective programs,” Chambers said.

Harding noted that SAMHSA, which funds states and communities, has four separate divisions with their own appropriations: substance abuse prevention, substance abuse treatment, mental health, and data and quality.

She noted it is difficult to integrate programs within the agency, let alone in the outside world. But SAMHSA recently initiated the Center for Prevention Implementation Methodology (CePIM), which is applying both the mental health and substance abuse divisions of SAMHSA to four programs focusing on underage drinking, suicide, school programming, and community. For its 2015 budget, SAMHSA has also proposed using funds allocated for substance abuse prevention and offering this funding to mental health communities so they can add a substance abuse component so that “community providers as well as our SAMHSA-funded communities can work together and learn from each other on the ground,” Harding said.

SAMHSA also participates in HHS’s Behavioral Health Coordinating Committee,which coordinates all 11 agencies within HHS. This committee focuses on early intervention, prescription drug abuse, teen drinking, integrating behavioral health care with primary care, and behavioral health communications. The committee meets monthly, and each of the agencies has representatives on subcommittees. “We are working much closer together and getting results at the federal level,” she said.

One workshop participant pointed out a program under development by the Community Preventive Services Task Force of CDC that plans to offer a decision implementation support system. This learning system will assist decision makers to identify and select programs and evidence-based strategies so they can meet specific goals while matching their needs and financial or other constraints. The goal of the Task Force is to provide a dynamic system so there is a dialogue about how these programs can be implemented across sectors and how lessons learned can be shared to promote collaboration among decision makers across several sectors, the participant reported.

Rotheram-Borus noted the tension that can occur between needing funding specifically targeted for prevention and wanting cross-sector integration. She pointed out that the Department of Education authorizes prevention under several titles but that overall, states and school districts are not using those funds because of current budgetary constraints. She suggested that unless there is targeted and categorical funding for prevention, it is not likely to occur.

Perhaps there should be a separate agency for youth development at the federal level, rather than having prevention programs for youth spread out among so many different agencies as it is currently, suggested Brown as well as members of the child welfare and juvenile/family justice breakout group. Such an organization would avoid duplication of effort in the primary care, school, or child welfare settings, Palinkas noted. Chambers added that several members of the health care breakout group discussed having greater coordination around prevention programs for children and suggested it be done at the state level. Members of the group suggested that

state agencies “share the headaches” and work together to solve shared problems. “It seemed like where this had worked was at the top levels of the state system, including the governor’s office, where there was ability to see ways to incentivize the individual sectors,” he said.

Chambers noted that coordination at that level is especially important in regard to funding programs. “You often have this parsing out of different funds that are actually going to support the same population. So although the infrastructure to deliver programs would be at the local community organization level, the resources to support them need to be coordinated at a higher level,” Chambers said. Bruns added that “states are where resource decisions are made.” However, Jennifer Tyson, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, highlighted the importance of community engagement—that though a higher level should coordinate prevention programs, one should not forget the importance of communities knowing best their own structure and which programs are likely to work for them, as well as which local organizations are best suited to carrying out these programs. “The community should define how that sharing should happen because without that you will be underestimating how much they know about themselves, and how things operate on the ground,” she said.

PROVIDING MORE FINANCIAL SUPPORT FOR PREVENTIVE INTERVENTIONS AND THEIR IMPLEMENTATION

Several workshop participants noted that a major barrier in scaling up EBIs is a lack of funding for prevention programs as well as a lack of funding for their proper implementation. Bruns pointed out that specific budget requests and financial incentives for child-centered EBIs are declining and have not increased in the past decade. Budgets for mental health in general are on the decline, he added. Kimberly Hoagwood of the New York University School of Medicine pointed out that data from Kessler and colleagues (2005) show that 75 percent of mental health issues begin under age 24. However, in most states much more funding is used to pay for adult mental health systems than those for children.

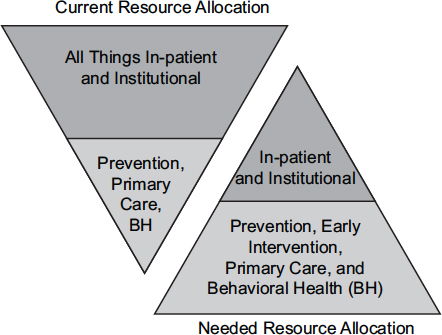

In addition, more budgets tend to be allocated for treatment rather than prevention. Bruns noted that behavioral health services have an overall penetration rate of about 10 percent, accounting for about 38 percent of total Medicaid child expenditures (Pires, 2014). However, that money is spent disproportionately on residential treatment and therapeutic group homes. This intensive residential care accounts for the largest percentage of total expenditures (19 percent) for only about 4 percent of children receiving behavioral health services. In Washington State in 2005, half the children who received services from two or more agencies in the Department of Social and Health Services used up half the budgeted mental health

resources (DSHS, 2011). Bruns pointed out in a graphic that an inordinate amount of resources go to these children with complex needs requiring inpatient or institutionalized care, and the challenge is to use more of those resources for prevention, early intervention, behavioral health, and primary care (see Figure 3-2). “We need to divert those dollars to upstream efforts,” he emphasized.

During discussion, Brent suggested there be some economic modeling of resource allocation that could indicate how much funding should be used for prevention programs versus treatment programs. This modeling could consider the cost savings of prevention programs and other factors that might more logically indicate how funding should be divided between the two types of programs.

As discussed in the workshop previously sponsored by the Forum (IOM and NRC, 2014), several participants suggested there be greater funding and infrastructure support for building capacity so prevention programs can be implemented more effectively. For example, Samuels pointed out that most states do not require clinical training of their social workers or

FIGURE 3-2 Flipping the triangle.

SOURCE: Dale Jarvis and Associates, LLC, 2014.

caseworkers, so most child welfare leaders work their way up through the system and do not necessarily have clinical training. There is the need to educate these people involved in carrying out prevention efforts about the consequences of child maltreatment, he said. Participants in the health care breakout group suggested there be state infrastructure support for implementation of EBIs. Members of the child welfare and juvenile/family justice breakout group suggested there be more focus on technical assistance and capacity building, including providing support for training and staffing of programs.

Bruns added that often EBI initiatives work better in academic research settings than in the real world because usual care in academic settings tends to involve smaller caseloads, high-quality supervision, and specialized training, compared to usually understaffed and insufficiently funded organizations that implement prevention programs. Instead of viewing these differences as confounding factors, he suggested trying to emulate them and provide the support needed for them in community settings. “It’s not that we’ve got a problem with the research, but these are the things we should be doing in usual care,” he said. For example, Washington State’s juvenile justice department developed an integrated treatment model that applied specific relevant types of evidence developed in an academic setting to residential care and parole. Research revealed that once parole staff was trained in functional family therapy, and 1 year after they began providing it, youths who did not receive such therapy were 48 percent more likely to get arrested and 55 percent less likely to be employed than those who received it (DSHS, 2011).

Dale Jarvis and Associates, LLC. 2014. About Dale Jarvis and Associates. http://www.djconsult.net/about (accessed September 4, 2014).

DSHS (Washington State Department of Social and Health Services). 2011. Effects of functional family parole on re-arrest and employment for youth in Washington State. http://www.dshs.wa.gov/pdf/ms/rda/research/2/24.pdf (accessed September 2, 2014).

IOM and NRC (Institute of Medicine and National Research Council). 2014. Strategies for scaling effective family-focused preventive interventions to promote children’s cognitive, affective, and behavioral health: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Kessler, R. C., P. Berglund, O. Demler, R. Jin, K. R. Merikangas, and E. E. Walters. 2005. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62(6):593-602.

NIH (National Institutes of Health) Toolbox. 2014. NIH Toolbox for the Assessment of Neurological and Behavioral Function. http://www.nihtoolbox.org/Pages/default.aspx (accessed August 8, 2014).

Pires, S. A. 2014. Children in Medicaid with behavioral health challenges. CMS Grand Rounds, May 8, 2014.

USPSTF (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force). 2014. Grade definitions. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/grades.htm (accessed September 4, 2014).

Zatzick, D. F., T. Koepsell, and F. P. Rivara. 2009. Using target population specification, effect size, and reach to estimate and compare the population impact of two PTSD preventive interventions. Psychiatry 72(4):346-359.