2

The Economic Returns from Higher Education

BOX 2-1 Important Points Made by the Speaker

• Postsecondary education increases the wages of some groups of students more than other groups of students.

• Students who earn associate’s degrees and certificates in technical fields often start out at salaries higher than the average for students who earn bachelor’s degrees.

• The number of associate’s degrees and certificates awarded has been growing at a substantially faster pace than the number of bachelor’s degrees earned.

In the opening presentation of the workshop, Mark Schneider, vice president and institute fellow at the American Institutes for Research and the president of College Measures, focused largely on how much different groups of students earn in the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth quarters after college graduation. The bottom line, he said, is that higher education does pay, but it pays more for some groups of students than others.

Higher education has gone through many reforms over the years, said Schneider, but most of these reforms have focused on who gets into college and why graduation rates at many institutions are unexpectedly low. The group he leads, College Measures, has been working on a different issue. It has worked with seven states−Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Minnesota, Tennessee, and Texas–to link student records with employment outcomes and salaries. It has been a “difficult political lift” to get states to make their data available and put the results in the public domain, said Schneider, who was named by the Chronicle of Higher Education as one of ten individuals who had a lasting effect on higher education in 2013. But the results have surprised educators, administrators, and policy makers and have revealed the value of programs designed to produce middle-skilled workers.

WHAT VERSUS WHERE A STUDENT STUDIES

Students go to college for many reasons, including becoming good citizens, learning to appreciate culture and the arts, and improving their well-being, Schneider acknowledged. But one of the most important reasons—if not the most important reason—is getting a good-paying job. Furthermore, wages can be measured, unlike most of the other benefits of college, which creates the potential to do performance-based budgeting for colleges using wage data. Eventually, it is likely that colleges will be judged on their performance in placing students in high-paying jobs.

An immediate finding from the data on wages after graduation is that the field in which a student majored has a much greater impact on earnings than the institution in which a student was enrolled. As Schneider put it, “What you study is more important than where you study.” Regional institutions in every state, and not just the flagship institutions, do an excellent job of putting students into the labor force. This is a “message of hope,” said Schneider, because it means that students in these institutions can do just as well economically as students in flagship institutions.

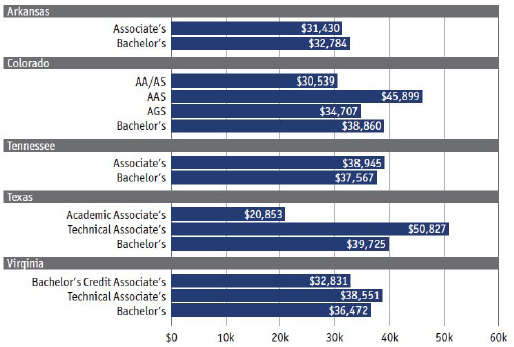

The data also have revealed the economic value of associate’s degrees and certificates. The initial earnings of graduates with associate’s degrees in technical fields generally are higher than those with bachelor’s degrees (Figure 2-1). For example, in Colorado, people who earn associate’s degrees in applied sciences make over $45,000 compared with less than $39,000 for those who earn bachelor’s degrees, across all majors (although people who earn other kinds of associate’s degrees earn less on average than the earnings for bachelor’s degree graduates). Admittedly, Schneider

observed, the group of people earning bachelor’s degrees encompasses a much larger group of majors than are represented by associate’s in applied sciences, and people with bachelor’s degrees tend to have a steeper earning trajectory than people with associate’s degrees over time, according to Census data. Nevertheless, “the technical associate’s degree is a valuable degree,” Schneider said. “The whole point is that there are jobs out there, these technical mid-skill-level jobs, that can put you into the middle class. Even if you may have been better off with a bachelor’s degree, a $45,000 or $50,000-a-year job is a lot better than not having anything.”

The data also demonstrate financial outcomes differences among institutions. For example, data from Colorado showed that Red Rocks Community College produced students with the highest average salaries among those who received associates degree in applied science. According to Schneider, the college’s success lies “in basic education practices. They talk to their students. They give them guidance. They give them counseling. They tell them how to manage debt. They tell them how to manage their time.” In general, Schneider said, the best community colleges are ones “with good presidents, good leadership, that work very closely with the local community and establish programs … that are responsive to the regional economy.”

Bachelor’s degrees remain the most commonly earned postsecondary degree in America. However, associate’s degrees and certificates have been growing at a substantially faster pace than bachelor’s degrees, and the number of associate’s degrees and certificates awarded annually are now roughly equivalent to the number of bachelor’s degrees.

DIFFERENCES AMONG FIELDS AND INSTITUTIONS

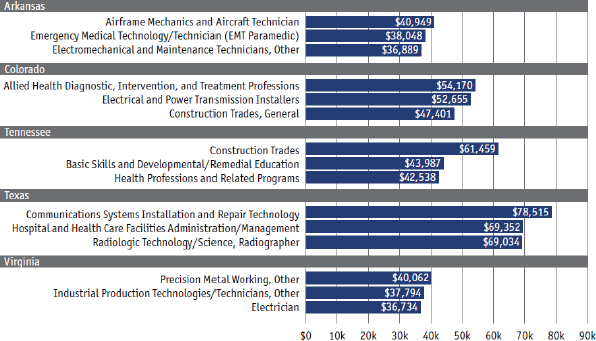

Turning to specific fields, Schneider noted that students who earn longer term certificates (those that take between one and two years to complete) and who focus on skills that can be used to “keep things working” are highly paid (Figure 2-2). Examples include airframe mechanics, maintenance technicians, electrical and power transmission installers, construction trade workers, communications systems installers, and precision metal workers. Some of these data were surprising even to the states where they were gathered. For example, the state of Tennessee did not know that people with certificates in the construction trades were the highest paid graduates in the state. “If you know how to build something, or you know how to keep something working, not surprisingly, you’re going to make a middle-class wage,” said Schneider.

FIGURE 2-1 Graduates with associate’s degrees in technical areas make more on average in their first year than do students who earn bachelor’s degrees. Key: AA/AS = Associate of Arts/Associate of Science; AAS = Associate of Applied Science; AGS = Associate in General Studies. SOURCE: Schneider (2013). Higher Education Pays: But a Lot More for Some Graduates Than for Others. Retrieved from CollegeMeasures.org. Website: http://collegemeasures.org/esm/.

FIGURE 2-2 Completers of longer term certificate programs who keep things working or keep other people healthy earn especially high initial wages. SOURCE: Schneider (2013). Higher Education Pays: But a Lot More for Some Graduates Than for Others. Retrieved from CollegeMeasures.org. Website: http://collegemeasures.org/esm/.

People who earn longer term certificates in health fields—and thereby keep other people working—also are highly paid. Examples include emergency medical technologists, allied health diagnostic and treatment professionals, and radiographers.

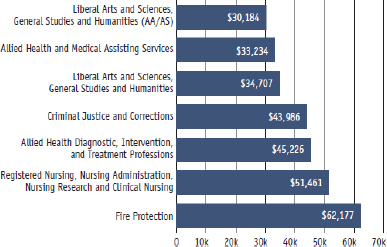

The data also reveal the extent of the differences in average earnings among those who receive associate’s degrees, from about $30,000 a year for associate’s degrees in the liberal arts and sciences, general studies, and humanities to more than $50,000 for associate’s degrees in registered nursing, nursing administration, nursing research, and clinical nursing and more than $60,000 in fire protection (Figure 2-3). Similarly, data from other states show that the median initial earnings for technical associate’s degrees are two to three times the earnings for academic, non-technical associate’s degrees.

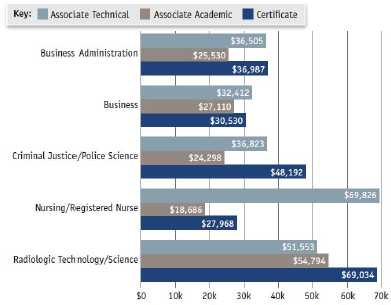

Compiling data from people who earn certificates is more difficult because of varying definitions of what qualifies as a certificate and because many people who get certificates also have some other kind of degree and may also have spent time in the workforce. Nevertheless, certificates in particular areas, such as criminal justice or radiological technology, pay off substantially (Figure 2-4). Schneider believes that students should know that there are more options available to them than liberal arts degrees.

Schneider also looked briefly at the growth of earnings over time. In some cases, such as biology majors, growth in average earnings is substantial, because some portion of biology majors become doctors eventually, even if they begin in low-paying jobs. But in general, low-paying professions right out of college are still relatively low-paying ten years after college, said Schneider. However, he also acknowledged that students who major in the liberal arts can learn skills that improve their employability, such as how to use and manage databases, how to do basic statistical analyses, how to use programs like Word and Excel, and how to write well.

As Schneider said, his thinking about higher education revolves around five questions:

- Am I going to get in?

- What is the graduation rate?

- How long is it going to take?

- How much is it going to cost?

- What am I going to get in return?

These questions are designed to reflect many of the realities of higher education, said Schneider. For example, many students take six or more years to get through a four-year college.

The data-driven approach he has taken does have some limitations, he observed. For example, some students with bachelor’s degrees are going back to school to get more technical associate’s degrees and certificates, and the effects of these decisions can be hard to measure. Also, students can leave one state and enter another, which skews the results using today’s state systems. States could share data, or the federal government could generate data through the Federal Employment Data Exchange System, Social Security data, or tax data, but many obstacles would have to be overcome to do so.

In closing, Schneider mentioned some intriguing ongoing changes in higher education. One is the growth of online learning and degrees. Although the path forward is not yet clear, change is likely to be rapid and pervasive. Schneider believes we are at the beginning of a technological revolution in the delivery of education. There are going to be failures and false starts. We need to tap technology to deliver education, because the way we do it now is too expensive.

In addition, he mentioned the growing interest in competency-based education, where students are recognized for mastering certain bodies of knowledge rather than the number and types of courses they have taken. “Rewarding students for knowing and being able to do things rather than sitting in a classroom for 42 hours is an interesting and fundamentally important change.”

Schneider also pointed to the political opposition that exists to gathering information about students and outcomes, especially at the federal level. Today, states own student records as well as the unemployment insurance data from which wages can be derived, which is why these comparisons are occurring state by state. States have these data and could merge them. “We as a nation have to get more serious about building the infrastructure to track students into the workforce.”

FIGURE 2-3 The initial earnings of graduates from popular Colorado Associate’s degree programs vary widely. SOURCE: Schneider (2013). The Initial Earnings of Graduates from Colorado’s Colleges and Universities Working in Colorado. Retrieved from CollegeMeasures.org. Website: http://collegemeasures.org/esm/.

FIGURE 2-4 Students who earn certificates in Texas often earn more initially than do those who earn technical or academic associate’s degrees. SOURCE: Schneider (2013). The Initial Earnings of Graduates of Texas Public Colleges and Universities. Retrieved from CollegeMeasures.org. Website: http://collegemeasures.org/esm/.