5

Assessing Core Competencies in Nursing Credentialing

MEASURING CORE COMPETENCIES IN MEDICINE USING TRADITIONAL AND ALTERNATIVE ASSESSMENT METHODS: LESSONS FROM THE ACCREDITATION COUNCIL FOR GRADUATE MEDICAL EDUCATION (ACGME)

Eric Holmboe, ACGME

Leaders of the medical profession have realized over the past 15 years that traditional physician training models were not likely to meet a population and health care system’s needs (Frenk et al., 2010), Holmboe said. Traditionally, curriculum has driven medical education objectives and clinician assessment efforts, which have remained loosely related concepts. In a competency-based education model, clinician competencies and training outcomes should flow from population and health system needs, which should also drive curricula and assessment programs, he said.

Health profession training programs, in general, are increasingly focused on the Triple Aim of improving the patient experience of care, improving the health of populations, and reducing health care’s per capita cost. The professional self-regulated assessment system in physician training is evolving to reflect this new shift in focus. The assessment system includes an accreditation component for education programs and the certification and credentialing process for individuals (which tests what they have learned). Although specialty certification—a third piece of the system—is still technically voluntary, Holmboe said, an increasing number of employment settings require it.

In a competency-based medical education system, residents and fellows must also play an active role in creating and assessing their own

competence, he said. Within the training program, residents should complete a series of assessments that involve direct observation, audit of performance data, multi-source feedback (which increasingly includes patient feedback), simulation, and in-training examination. This approach creates a rich source of data that clinical competence committees analyze, as they decide whether an individual should enter unsupervised medical practice. The process provides feedback opportunities for trainees, trainers, and residence program directors, among others. The result is a physician accreditation system that now has a continuous quality improvement perspective.

“Milestones” and “entrustable professional activities” underpin the system and, together, facilitate a common language and training roadmap, which may include more than one path to competence and potentially makes the process of change easier (citing Ten Cate and Scheele, 2007). In the past, residents were rated on a nine-point scale, with ratings of 1-3 being unsatisfactory, 4-6 satisfactory, and 7-9 superior.

An example of a general “milestone” template now being used in graduate medical education programs is shown in Table 5-1. The example shows the increasing complexity of what residents are expected to be able to accomplish when taking a patient history. No subjective words, such as “satisfactory” or “unsatisfactory,” are used. At level 1, “Acquires a general medical history,” the milestone is rather general. At level 2, residents are expected to be able to “acquire a basic history, including medical, functional, and psychosocial elements.” The milestones become increasingly complex and, by level 5, residents should be able not only to gather the appropriate information from the patient, including subtle or difficult information, but also to do so efficiently and to prioritize what they learn. Level 5 is also considered to be “aspirational,” said Holmboe, meaning most residents will not achieve this level in training but rather in the first years of practice.

Monitoring milestones should enable residents, fellows, and training programs to better judge an individual’s trajectory toward acquiring competency. Residents’ trajectories are not necessarily linear and may advance along the continuum at different rates. By monitoring milestones, program directors (and residents) can better judge an individual’s trajectory, enabling intervention and remediation. An individual resident’s ratings can also be compared to the average ratings of all other trainees in a residency program.

TABLE 5-1 Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Anatomy of a Milestone

| Patient Care—History (Appropriate for Age and Impairment) | ||||

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | Level 4 | Level 5 |

| Milestone 1. Acquires a general medical history | Milestone 2. Acquires a basic history including medical, function, and psychosocial elements | Milestone 3. Acquires a comprehensive history integrating medical, functions, and psychosocial elements Milestone 4. Seeks and obtains data from secondary sources when needed |

Milestone 5. Efficiently acquires and presents a relevant history in a prioritized and hypothesis-driven fashion across a wide spectrum of ages and impairments Milestone 6. Elicits subtleties and information that may not be readily volunteered by the patient |

Milestone 7. Gathers and synthesizes information in a highly efficient manner Milestone 8. Rapidly focuses on presenting problem and elicits key information in a prioritized fashion Milestone 9. Models the gathering of subtle and difficult information from the patient |

SOURCE: Holmboe, 2014.

“Entrustable professional activities” are the routine professional activities of physicians within a specialty and subspecialty, said Holmboe (citing Ten Cate and Scheele, 2007). “Entrustable” means a practitioner demonstrates the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be trusted to perform a particular activity unsupervised (but not necessarily independently). Too often, he said, people are judged competent to do their work based on “time proxies”—completing an internship or a residency, for example—when research has shown that time proxies are not necessarily reliable indicators of individual skills.

Assessment processes must be able to evaluate the most important components of the curriculum, one of which is the actual clinical care residents provide and experience during their training. Much research has shown the importance of ongoing observation and feedback from an expert clinician during training. At the same time, much effort has been put into finding the “perfect” assessment forms, which do not exist, Holmboe said. Assessment forms need to align with the purpose of the assessment and the curriculum.

Many dimensions of systems-based practices, quality care, and patient safety are not well measured through traditional assessment methods. Work-based assessments may be improved through direct observation, patient surveys, multi-source feedback, and local assessment practices to ensure continuous quality improvement at the care site. Additional criteria for assessment could include interprofessional team care, effective use of clinical decision support, and effective communication with patients, within teams, and among physician colleagues. Additionally, electronic health records may allow for embedding work-based assessments into routine clinical work, making them easier to perform and providing ongoing, longitudinal, real-time feedback.

Growing research showing that the clinical system is not providing high-quality care underscores the importance of ensuring that the educational system is better integrated with the clinical system, concluded Holmboe. ACGME is trying to define more precisely and descriptively the outcomes residency programs should be achieving, so they can design appropriate curriculum and assessment systems.

ASSESSING OUTCOME PERFORMANCE COMPETENCIES IN PHYSICAL THERAPY

Jody Frost, American Physical Therapy Association

For more than two decades, assessment has been a key issue in the physical therapy profession, began Jody Frost. The American Physical Therapy Association’s (APTA’s) Clinical Performance Instrument (CPI), is used to assess students during their clinical educational experiences. Physical therapy programs are not required to use the CPI, but the vast majority of programs voluntarily do.

In the 1990s, APTA developed the first version of its CPI (Roach et al., 2012), in response to the needs of practitioners for increased productivity and cost containment, proliferation of student assessments without

validity and reliability, and the risk of losing clinical education practice sites. In the first phase, planners began with a literature review and looked for trainee knowledge, skill sets, and behavioral outcomes that clinicians and academicians would endorse as essential in clinical practice. In Phase II, APTA planners hosted multiple forums in the United States and Canada to collect early input on the draft instrument. Planners also conducted pilot studies and field studies before modifying the CPI.

A decade later, APTA embarked on its second iteration of the CPI (Roach et al., 2012). in response to a number of factors (e.g., changes in curriculum requirements and transition to the Doctor of Physical Therapy (DPT) professional degree, poor standardized training in performance assessment, results of research investigations conducted on the first version of the CPI, and feedback received from users of the first CPI). Changes included

- streamlining from 24 to 18 outcomes-based performance criteria, which focus on situations that occur in every clinical setting and practice, as well as criteria which can be rated during all clinical experiences;

- changing from the more subjective visual analog scale to a rating scale with six well-defined, and statistically significant anchors;

- Removing academic jargon; and

- Providing trainees with comments and other qualitative information to provide context for individual ratings.

These modifications aimed to improve validity, reliability, acceptability, and feasibility. The initiative also attempted to avoid certain legal issues that arise from poor trainee performance by incorporating an early warning system with a defined timeline for student improvement; providing candid and objective evaluation; and facilitating dismissal when warranted.

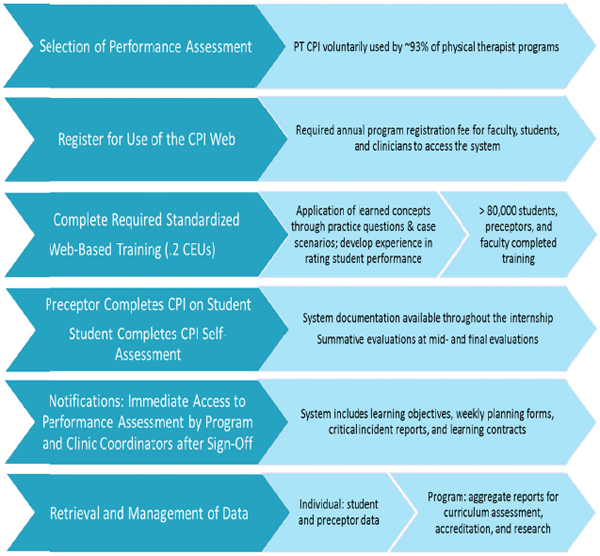

The current instrument is similar to the approach used in medicine, Frost said; it is a multidimensional, Web-based tool, with multiple opportunities to assure consistency in ratings across clinical settings. Figure 5-1 lists the steps in the CPI assessment process. Preceptors assess their students, and students also complete self-assessments. “Red flag” items indicate significant concerns that warrant an intervention. The online system automatically generates a critical incident report if a “significant concerns” box is checked. Once checked, the preceptor, center coordinator of clinical education and academic program may need to negotiate a

FIGURE 5-1 Steps in the CPI assessment process.

NOTE: CEU = continuing education unit; CPI = clinical performance instrument; PT = physical therapist.

SOURCE: Frost, 2014.

learning contract regarding expected student performance. If the “significant concerns” box is checked by the evaluator, a notice also automatically goes to the student, training site coordinator, and academic program coordinator for action. All users of the system complete the online, standardized training to improve reliability.

Based on her experience, Frost offered some general guidelines. Any assessment system has to be accessible, affordable, and standardized for all users. Furthermore, developing clinical performance assessment tools requires collaboration and listening, soliciting feedback, debate, balancing professional buy-in and psychometric rigor, accounting for legal considerations, standardized training, enhancing credibility by incorporating

all elements of effective assessment, minimizing academic jargon, and providing support for the transition to a Web-based tool. Moreover, the clinical assessment components must be easily updated as curriculum changes occur and patient care evolves.

Frost provided further advice specific to nursing credentialing, starting with, “You have to start the process and hope that, over time, people come on board. If you wait for everybody, you will never get it done.” She suggested that nursing: (1) develop consistent, profession-based outcome competencies for nursing graduates; (2) based on these competencies, develop psychometrically sound, outcome-based assessments for students that incorporate critical components and can be used throughout clinical education; and (3) provide consistent training on how to use assessment instruments to increase their reliability.

Frost concluded by suggesting the following areas for action:

- Improve mechanisms to make outcomes performance assessments more dynamic in a changing health care environment.

- Incorporate the patient’s perspective in feedback about the care trainees provide.

- Ensure assessments are sensitive to preceptors’ time demands.

- Explore the potential for some common attributes of outcomes assessments to be shared across professions (e.g., safety, accountability, professionalism, and communication).

- Create a funded, centralized resource for developing assessments that can collect aggregate data across health professions.

CORE COMPETENCIES IN ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING CREDENTIALING AND CERTIFICATION

Laurie M. Lauzon Clabo, MGH Institute of Health Professions

The American Association of Colleges of Nursing’s Advanced Practice Registered Nursing Clinical Training Task Force (“the Task Force”) has a project currently under way to re-envision clinical training for Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs). One of the Task Force’s charges is to consider core competency assessment (across roles and patient populations) as a potential component of a new clinical training approach. Although a standardized competency-based system is desirable, the four relevant professional organizations appear to be moving along separate paths, reflecting unique competencies for which it is not known

whether common core competencies exist nor whether such competencies are different from those required for other types of nursing practice. The Task Force’s current work could be used to highlight conceptual and methodological issues that may affect nursing practice as a whole.

Among the convergent forces prompting this examination are increased demands for APRN services in the health care sector, which strains training programs and increases competition for scarce clinical training sites and preceptors. The strain comes not only from the growth in numbers, but also in the complexity of practice. Preceptors say students from different programs, who supposedly are at the same point in their educational trajectory, often demonstrate very different skill levels.

To date, a coordinated, systematic approach has not been taken to identify either common competencies for all APRN roles or a standard assessment framework across APRN specialties (midwives, nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, and nurse anesthetists). Moreover, there is no finite set of nationally recognized, consensus-based common core competencies for APRN assessment. For example, although some standards rely on “clinical hours” requirements, there is no evidence in the literature that these are an effective proxy for core competencies.

Gathering evidence and conducting research about core competencies involves several challenges. In the APRN field, current competency documents have limited conceptual clarity across documents, with no single common definition of competency used and variation in the scope and clarity of individual competencies, which range from long lists of psychomotor skills (completely divorced from professional judgment) to complex cognitive skills (posing serious measurement challenges). The Task Force must also determine who should participate in the identification of competencies; create a broadly understood, accessible, and efficient assessment system; and ensure that assessment goes beyond entry level and reflects the development of additional or advanced competencies through continuing professional development and practice. The Task Force also is considering whether milestones relevant to APRN core competencies can be identified, along a continuum from pre-clinical experience to graduation and beyond.

To strengthen the Task Force’s efforts, research activities should focus on identifying essential competencies across multiple dimensions (educational preparation, role, population focus, and continuing professional development); developing effective and efficient assessment strategies; clarifying the relationship between competencies and patient outcomes; taking into account different units of analysis for nursing

practice in many settings; and exploring the relationship between individual and team interprofessional competence.

QUESTIONS AND COMMENTS

Should greater emphasis be placed on assessing whether providers are capable of performing competently, or is it more a question of whether providers perform consistently and reliably in every circumstance?

Holmboe said this dilemma underscores the importance of embedding performance assessment as an ongoing activity, so that competence can be demonstrated in a variety of situations. For example, in medicine, residents treat patients who appear in the clinic, yet these may not be the same kinds of patients residents will care for when in practice. Their training needs to include the opportunity to manage such patients over a reasonable time period, Holmboe concluded.

Lauzon Clabo agreed, adding that, “given the complexity of the health care system and the patient populations,” assessment must be viewed not as a single, isolated event, but a process that occurs over time. Training programs cannot just hope that trainees will encounter the same type of patient in training and practice, that the preceptor will treat those patients according to current evidence, and that the preceptor will impart that knowledge effectively. Some variability in the training experience is removed by allowing multiple assessors over multiple periods of time to observe students with multiple patients.

As certification bodies update eligibility criteria, and as nurses obtain education through various modalities, can the influence that formal education has on the value of certification and on patient outcomes be determined?

Frost said some research has shown that physical therapy licensure examinations (which are more of a test of the educational process) and clinical performance instruments, actually evaluate different aspects of readiness to practice. In fact, she said, even students who do not complete their clinical education are capable of passing the licensure examination. For that reason, people should be cautious in assuming that licensure alone is an adequate indicator of provider performance. Like other panelists, she underscored the importance of context in assessments, noting that students who perform well in outpatient settings may

not do as well in inpatient situations, where patients are sicker and in a more complex and more varied situation.

Holmboe said that in medicine certification is often equated with passing an examination. While those who do not pass do not perform as well as those who do pass, this measure explains a relatively modest amount of practice variations. Certification should represent both passage of a standardized examination and clinical competence, but research has shown that the latter often receives insufficient attention.

Lauzon Clabo said the situation in nursing becomes even more layered when taking into account the multiple degree levels possible prior to entering practice. Thus, it becomes even more important to isolate these factors and reflect them in assessment models.

What is the role of ongoing, periodic performance evaluation? Does a credential cover an entire career?

Research conducted with physicians indicates that, on average, performance declines over time, especially for those in solo or small-group practices, Holmboe said. This has led to recognition that competence assessment should be ongoing, but the means for accomplishing that is undetermined—current models tend to be sporadic, narrow, and probably not very effective. Instead, ongoing self-assessment mechanisms should be embedded in practice. A good example is data registries that allow ongoing feedback to physicians and teams regarding how well they are caring for patients with specific diagnoses.

Frost added that ongoing assessment strategies have to consider that professions are changing, and individuals need to be measured against competencies relevant today, not when they graduated from their educational institution. Ideally, ongoing assessments should reflect the individual’s career stage and involve both education and practice performance measures.