In the 30 years since SBIR started at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), there has been a profound change in the agency’s vision for itself. Most fundamentally, NIH is now more interested in and committed to “translational research”—activities that will help to move technologies from the laboratory into the marketplace. Among many initiatives, NIH has formed an entire organization devoted to this effort, the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

The NIH Institutes and Centers (ICs) have in general become more interested in SBIR/STTR in part because of this greater commitment to translational research. Not all ICs have made major changes to their operations in response, but some have done so, and new models of program management are emerging at some of the larger ICs as a result of the new focus on translational research.

This chapter focuses on two of the largest ICs—the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). It also reviews some of the other agency-wide initiatives, most notably the occasional provision of awards considerably larger than stated in the SBA guidelines (these awards are legal on the basis of waivers provided by SBA).

NEW MANAGEMENT MODELS FOR SBIR/STTR

For almost all ICs, the traditional management model for SBIR/STTR at NIH has been to employ one or two staff members to act as expert advisors in relation to program questions. They complement program officers with broad responsibility for administering the SBIR and STTR programs.

This model has some advantages. It is relatively low cost, which has been an especially important consideration when administrative funding was not available through the SBIR/STTR programs and when ICs tended to see the programs as a tax on their other research activities. The model also ensures that program officers with deep expertise in IC interests and priorities manage SBIR/STTR awards. Some of the larger ICs did assign the management of SBIR awards to an individual staff member who effectively became the program officer for SBIR/STTR, but this was not a standard model. Most ICs found that they had too few awards to justify such a full-time assignment.

However, this approach has two disadvantages: first, it leaves companies connected directly to program officers that are experts in the research areas that they fund but likely with little commercialization experience; and, second, it does not provide for the accrual of expertise—for example, on regulations or marketing—within the IC.

Beginning in the mid-2000s, some ICs developed new models for managing SBIR/STTR. At NCI, the NCI SBIR Development Center has become the locus for all SBIR activities, including awards and the company liaison.1 At NHLBI, the Office of Translational Alliances and Coordination (OTAC) has become a provider of deep expertise to both program officers and companies in the many areas that impinge on biomedical commercialization, including intellectual property, capital acquisition, marketing, and regulation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Other ICs are developing their own models, but these two approaches affect two of the biggest ICs and are most developed. They are discussed in more detail below.

The NCI Model: Building on the National Science Foundation (NSF) Management Model

Starting in 2007, NCI moved rapidly to shift the traditional NIH management model for SBIR/STTR to one much closer to that pioneered by NSF.2 NCI is the largest IC at NIH and accounts for about $119 million in SBIR/STTR funding, out of about $750 million at NIH overall.

The new model is deployed through the NCI SBIR Development Center (NCIDC). NCIDC funds nine full-time program directors, each of whom holds a doctorate and is working in a particular technical area within NCI’s portfolio of activities. The NCIDC is led by a full-time director and currently hosts two AAAS Science and Technology Policy Fellows.

The NCIDC activities cover the entire timeline of SBIR activities. Staff are responsible for outreach to applicants and for coaching potential applicants to

_______________

1This is in many respects similar to the NSF model discussed in the committee’s forthcoming report on SBIR at the National Science Foundation.

2See National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, SBIR at the National Science Foundation, Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, forthcoming.

improve the quality of applications. They oversee and actively manage currently funded projects, replacing the Program Manager who fulfills this function at other ICs. As the award ends, NCIDC staff help to match awardees with potential sources of Phase III funding. This model is indeed very close to that developed at NSF.

In addition, NCI has developed a new funding strategy—Bridge awards—and a new investor forum for bringing together NCI SBIR/STTR companies and potential investors.

Bridge Awards

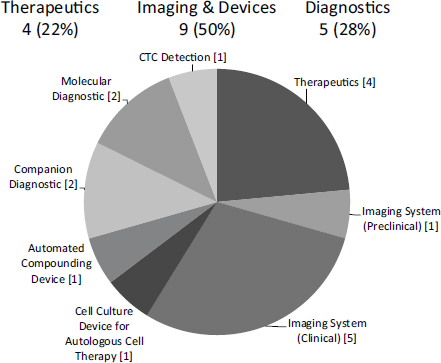

NCI has pioneered a variant on Phase IIB awards, which are designed to support companies entering clinical trials (see Chapter 4 for more detail). It has made 16 $3 million Bridge awards since the program started in FY2009. Onehalf are in imaging and devices, and about one-quarter are in therapeutics and diagnostics respectively (see Figure 3-1). These awards account for about 15 percent of all Phase IIB awards made by NIH during fiscal years (FY) 2009-2014 (see Chapter 4).

FIGURE 3-1 Distribution of NCI Bridge awards by sub-sector, FY2009-2013

SOURCE: Michael Weingarten, “Bridging Technologies from the Lab to Market: the NCI SBIR program,” November 13, 2014.

Bridge awards provide SBIR/STTR firms up to $1 million per year for up to 3 years. They are specifically designed to help companies prepare for and enter the clinical trials process. They help companies connect with potential funders and strategic partners earlier in the process than would normally be the case by providing partners with a boost to the company that does not dilute their equity. While a funding match by a private-sector investor is not strictly required, companies with a match can and do have a competitive advantage.

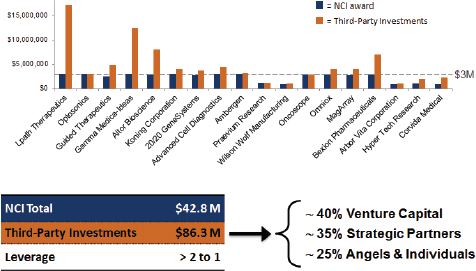

In some cases, investors and other third parties have generated large matching funds. Overall leverage is slightly better than 2:1 (see Figure 3-2), and most Bridge projects report more than the “recommended” 1:1 match. About 40 percent comes from venture investors, 30 percent from strategic partners, and 20 percent from angel investors.

To date, participating companies have reported positive experiences with Bridge awards. Dr. Roger Sabbadini of the firm Lpath, contacted for this report, said that other Institutes should follow NCI’s example. He is sufficiently convinced of its value now that he serves as reviewer for NCI Bridge awards.

However, acquiring the matching funds for these awards is a time- and resource-intensive endeavor for companies. Forty-three respondents from the 2014 Survey reported that they had to find matching funds. Of these, 44 per-

FIGURE 3-2 Matching investments for Bridge awards at NCI.

NOTE: See the Lpath case study in Appendix E.

SOURCE: Michael Weingarten, “Bridging Technologies from the Lab to Market: the NCI SBIR program,” November 13, 2014.

cent said that it took at least 2 months of full-time equivalent effort for senior management.3

There are also potential pitfalls to selecting SBIR/STTR projects in a process akin to that of a small venture firm. In particular, the risk exists that interests in short-term commercial perspectives will predominate over the potential for more broadly spread societal benefits. Also, venture firms often provide extensive ongoing management support and marketing connections, neither of which NCI provides. Further, venture firms are, of course, the source of further rounds of funding.

I-Corps

The I-Corps program is described in more detail under NIH-wide innovations below. However, it is important to note here that the I-Corps initiative, although open to all ICs, has been driven in large part by NCI SBIR leadership, and that NCI continues to utilize most of the available slots in the program.

Investor Forums

Again building on initiatives from other agencies, NCI has organized a number of investor forums in recent years. Like the Navy Opportunity Forum, these aim to bring together companies and potential investors. At the November 2014 forum in Santa Clara, California, for example, 28 companies presented their technologies, with more than 200 people in attendance.

According to NCI, the investor forums have overall generated more than $300 million in deals, with $230 million in 2010 alone, primarily through a $200 million deal between Zacharon and Pfizer. In 2013 Zacharon was acquired by BioMarin for $10 million.

The NHLBI Model4

The new approach at NHLBI emerged from a growing understanding that commercialization for biomedical innovation presented major challenges that the original SBIR/STTR program management model was not addressing. An initial assessment of the issue was undertaken by a high-level committee, which included staff familiar with the SBIR program and senior IC management. The team produced a detailed and far-reaching report titled Enhancing the Return on

_______________

32014 Survey, Question 29, N=43.

4Information in this section is drawn from internal agency documents made available as well as two briefings provided to the NRC committee by NHLBI staff.

the NHLBI SBIR/STTR Investment Team (ERNSIT),5 which became the basis for a number of pilots and changes at NHLBI.

The report identified some key challenges for biomedical commercialization in general, and also some particular challenges for those working in the technical areas covered by NHLBI. Key general challenges included the following:

- Funding gaps exist before and after SBIR/STTR programs.

- Small businesses lack biomedical product development and business knowledge.

- Outreach and monitoring results are challenging because many small businesses get started, shut down, move, change names.

- NIH policies (e.g., review) do not always align with what is needed for SBIR/STTR awardee success.

- In some cases, program officers and grants management specialists might lack expertise in advising small businesses on commercialization issues and managing awards.

ERNSIT recommended some significant changes, most notably that NHLBI should introduce an entirely new office staffed with personnel dedicated to program activities, which would provide “scientific, business management, regulatory, and outreach expertise to coordinate and accelerate translational activities at the NHLBI.”6

Within this new structure, ERNSIT also recommended:

- Enhanced and expanded partnerships for outreach

- More strategic use of funding opportunity announcements to align SBIR/STTR with Institute priorities

- Strategies to address pre and postSBIR funding gaps

- Improved evaluation and assessment

All of these recommendations were adopted by the NHLBI governing council in May 2010, and NHLBI’s Office of Translational Alliances and Coordination (OTAC) started work in 2011.

The work of OTAC can be divided into four broad areas: expert advice to program officers and companies; outreach and training before Phase I; Phase I and Phase II commercialization support; and support after Phase II.

_______________

5The ERNSIT report was an internal report to the director of NCI. A summary of the ERNSIT report recommendations were provided by NHLBI in the NHLBI Office of Translational Alliances and Coordination and the SBIR/STTR Program, “Lab to Health,” presentation to Academies, May 26, 2015, p. 7.

6The NHLBI Office of Translational Alliances and Coordination and the SBIR/STTR Program, “Lab to Health,” presentation to Academies, May 26, 2015, p.7.

Expert Advice

Expert advice requires access to experts, and OTAC has hired and otherwise acquired a portfolio of expertise well suited to the needs of SBIR/STTR participants. These include as full-time staff:

- A regulatory specialist with 8 years of experience at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA);

- An entrepreneur in residence who has worked at a large pharmaceutical company and is an investor;

- An entrepreneur in residence who is also an earlystage investor and serial entrepreneur;

- A grants management specialist; and

- A business development/marketing expert with more than 15 years’ experience with small innovative businesses and startups.

OTAC also includes a patent examiner on detail from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office with extensive experience in intellectual property issues (additional expertise in some of these areas is also available from the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health, a part of the Centers for Disease Control).

Proof-of-Concept Programs (pre Phase I)

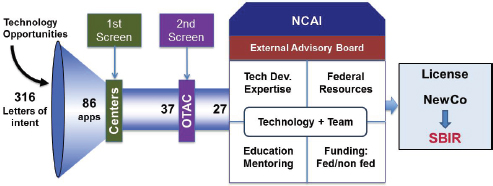

OTAC operates two proof-of-concept programs: the NIH Centers for Accelerated Innovation (NCAI) and the Research Evaluation and Commercialization Hubs (REACH) program.7 These programs aim to address three issues identified by the ERNSIT report: lack of funding for very early-stage commercialization activities; lack of commercialization expertise among scientists; and lack of access to additional commercialization resources.

There are three NCAI Centers located respectively at the Boston Biomedical Innovation Center, the Cleveland Clinic, and the University of California in Los Angeles, and three REACH centers located respectively at the University of Minnesota, the Long Island Biomedical Hub, and the University of Louisville.

Figure 3-3 shows the pipeline from letters of interest from researchers through company formation and SBIR application. It shows the different screening filters from the REACH and NCAI processes.

Targeted Funding Opportunities

The ERNSIT report recommended that NHLBI try to target its SBIR resources more strategically. Efforts to do so have focused on improved definition

_______________

7REACH is a trans-NIH program that is managed by a trans-NIH oversight committee, chaired by NHLBI based on their experience with these issues. NHLBI does not operate the REACH program.

FIGURE 3-3 NCAI proof-of-concept support.

SOURCE: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

of topics and expanded use of targeted funding opportunity announcements (FOAs). While there is a set-aside budget associated with targeted FOAs, NHLBI staff consulted for this study note that detailed research proposals still come from the investigator community. Targeted FOAs are usually reviewed in-house by the IC using its own review panels, which some NHLBI staff believe offer a substantial advantage for SBIR/STTR applications over NIH’s Center for Scientific Review (CSR) reviews. They note that this approach allows NHLBI to select reviewers with the appropriate combination of product development and scientific expertise necessary to effectively review small business program applications. Finally, budgets can be set aside for the targeted areas, which is not the case for standard topics provided through the annual Omnibus Solicitation. Some ICs such as NHLBI and NCI view the annual contract solicitation as an opportunity for targeted funding announcements, because it meets all of the criteria for such identified above.

It appears that funding for targeted FOAs is increasing as a percentage of SBIR/STTR funding. Estimates by NHLBI staff suggest that, excluding contracts, targeted funding opportunities now account for perhaps 15 percent of SBIR/STTR funding (see Box 3-1 for examples).

Training for Awardees

In addition to the I-Corps pilot program led by NCI, NHLBI participates in the Coulter College Commercializing Innovation (C3i) program. Covering topics such as market assessments, patentability assessments, and regulatory reviews, the C3i commercialization planning program seeks to support collaborative research that addresses unmet clinical needs in health care.8 NHLBI also partners

_______________

8C3i was launched in 2014 by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering and the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation. Biomedical Engineering Society, Coulter College. http://bmes.org/coulter, accessed October 1, 2015.

BOX 3-1

Examples of NHLBI Targeted Funding Opportunities

- Stem Cell-Derived Blood Products for Therapeutic Use: Technology Improvement (STTR RFA-HL-15-029, SBIR RFA-HL-15-030)

- Onsite Tools & Technologies for Clinical Research Point-of-Care (STTR RFA-HL-14-017, SBIR RFA-HL-14-011)

- Bioreactors for Reparative Medicine (STTR RFA-HL-15-004, SBIR RFA-HL-15-008)

- Human Cellular Models for Predicting Individual Responses to CFTR-Directed Therapeutics (STTR RFA-HL-15-026, SBIR RFA-HL-15-027)

SOURCE: NIH Annual SBIR Request for Applications.

with a range of national investor showcases and events, including those run by BIO, the American Capital Association, and AdvaMed. This effort to align with industry sector conferences focused on early-stage activities is a potentially important initiative.

Post Phase II Awards

NHLBI operates two award programs to help bridge the gap between the end of SBIR/STTR Phase II and full commercial opportunities. The Bridge awards are very similar to those provided through NCI and described in detail above. Bridge awards are for $3 million over 3 years, with an expectation of a 1:1 match from a third party.9

Uniquely, NHLBI also operates Small Market awards. These are focused on rare diseases and pediatric populations. Recognizing that these are more challenging areas for commercialization, the match expectation here is 1:3, that is, outside matches must total $1 million for a $3 million award (as with NCI, matches must be in cash and not in-kind and must come from outside the award-recipient company).10 Of course, awardees still have full access to the portfolio of experts working through the NHLBI OTAC.

Outreach Initiatives

To complement the outreach activities coordinated by the NIH Program Office (see Chapter 2, Program Management), the larger ICs have in some cases implemented their own activities. NHLBI has been especially innovative in using

_______________

9See RFA-HL-16-009 for details on the current request for Bridge proposals.

10See RFA-HL-14-012 for details on the current request for Small Market proposals.

social media for this purpose. It has hosted a series of virtual meetings using Google Hangouts, which have covered regulatory issues, commercialization, and intellectual property, thus providing access to OTAC experts in these areas.

OTAC has also developed a series of explanatory videos that are hosted on YouTube.11 These, in particular, permit access from locations far from Washington, and the two videos on managing processes prescribed by FDA have attracted 1,649 and 1,329 views, respectively.12

NHLBI hosts the Regional Innovation Conferences, partnering with local resources to put them on. These conferences serve a variety of purposes, including connecting SBIR companies to potential sources of Phase III funding. According to NHLBI, the most recent Boston Regional Innovation Conference allowed 19 local companies to present their SBIR technologies, of which 3 entered into materials transfer agreements and 1 received a $1 million funding round led by a venture firm.13 NHLBI also runs its own disease-specific conferences and worships, which have recently included workshops on Translating New Therapeutics for Sickle Cell Disease to the Market Place and Precision Therapeutics Delivery for Lung Diseases.

One of the challenges for small biosciences companies is to make the appropriate connections with what are effectively the primary sources of funding for clinical trials and then product development and marketing: big pharmaceutical companies. Given the enormous costs of drug development (estimated by the recent Tufts study as $2.6 billion on average14), connecting to the big pharmaceutical companies is essential but frequently difficult. In 2014, NHLBI sponsored a workshop on building an industry-government-academic partnership that attracted a large number of the world’s major pharmaceutical companies. While the impact of the SBIR/STTR programs remains to be seen, the committee believes that improving the pathway for connections between small companies and big pharma is of substantial value.

Building an IT Platform to Track and Manage Multiple Initiatives

As ICs develop more complex and ambitious programs, especially for outreach, it becomes necessary to develop an information technology (IT) platform that can accommodate and track all of these new activities and participants. NHLBI is now exploring the use of Salesforce as a technical tool to bring together a PI, an entrepreneurial lead, and a mentor.

_______________

11See http://bit.ly/NHLBI-YouTube.

12NHLBI, Small Biz Hangouts, “Conquering the (Regulatory) Basics—Navigating the FDA Website” and “First Contact with FDA,” accessed July 15, 2015. (See http://bit.ly/NHLBI-YouTube.)

13NHLBI op. cit. p.37

14Tufts Center for the Study of Drug Development, 2014 CCSD Report, http://csdd.tufts.edu/news/complete_story/pr_tufts_csdd_2014_cost_study, accessed June 16, 2015.

New Management Models: Summary

Both NCI and NHLBI have developed new management models for their SBIR/STTR programs that quite fundamentally challenge the standard model at NIH. The standard approach often suffers from a lack of commercial expertise among program officers. Meanwhile, survey evidence and case study discussions revealed considerable demand among awardees for more support in relation to commercialization—including in relation to FDA approval for clinical trials.

Of course, because they were initiated recently, it is too soon to determine whether these new approaches, while addressing a key challenge, are having a net positive impact on program outcomes, and indeed whether that impact is worth the additional cost of the more focused management structures that they require.

NIH-WIDE INNOVATIONS

Awardee Training and Education: The I-Corps Pilot Program

After a number of years during which NIH relied on a third-party provider to offer commercialization training for awardees (see Chapter 2, Program Management), the agency introduced in FY2014 a version of the I-Corps program previously deployed at NSF. The NSF I-Corps program brings together awardees, a marketing partner (usually a graduate student in business or a marketing professional), and a mentor for a concentrated period of commercialization analysis and planning. The program is based on a teaching curriculum called the Lean Launchpad, developed by Steve Blank, a serial entrepreneur at Stanford University. I-Corps offers participants an intensive entrepreneurial immersion course that uses the participants’ companies as the core learning medium. The 2014 I-Corps course had 11 class sessions and required a considerable commitment of time and effort from the participating teams. Final presentations were due 11 weeks after the initial meeting.

A key feature of the course is the requirement that participants must undertake at least 100 interviews with potential customers and partners. This extended listening exercise is designed to provide companies with important business information well before the product is ready to launch.

At NCI, the lead IC for the I-Corps program, participants are awarded a $25,000 supplemental award to pay for their participation. This participation provides the three-member teams with access to both instruction and peer connections via an I-Corps node (provided via a university). These teams include a C-level executive (e.g., CEO, CFO) from the company, an outside industry expert, and the principal investigator on the SBIR/STTR award.

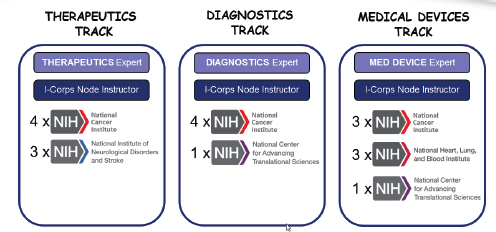

The I-Corps program is tailored to the specific needs of life sciences companies. It is organized around three tracks: therapeutics, diagnostics, and medical devices, each of which has a specialized instructor. ICs may participate in one or more of the tracks—NCI is the only IC to participate in all three (see Figure 3-4).

FIGURE 3-4 First-year participation in NIH I-Corps program, by track and IC.

NOTE: X = participants.

SOURCE: Andrew Kurtz, “The NCI SBIR Program: An Overview of New Funding Opportunities and Strategies for Employing Lean Startup Tools to Drive Success in Your Small Business,” AACR presentation, April 20, 2015.

Multiple ICs participated in the first cohort (including NHLBI). The initial cohort of 19 companies included 3 awardees from NHLBI. IC staff expect this program to expand substantially in the near future, assuming results are as projected.

NCI has provided a review of initial outcomes from the first pilot program in FY2014. The 19 teams conducted a total of 2,128 “discovery” interviews. More than 80 percent found the I-Corps program to be good or excellent and would recommend it to other companies involved in the NIH SBIR program.15 Companies developed specific hypotheses that underpin their business models and then found ways to test them, especially against feedback from customers and partners. The process was carefully structured and tracked on a weekly basis.

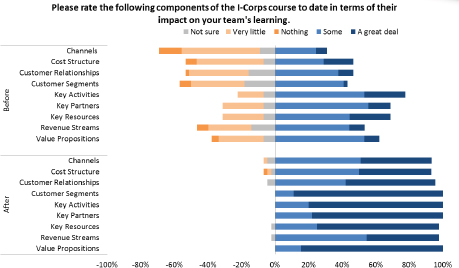

More generally, participation in the program improves company knowledge about core aspects of their business. Figure 3-5 shows the before and after state of knowledge for participating companies in relation to key aspects of their operations.

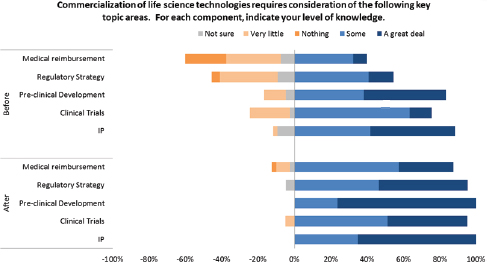

These data indicate an impressive improvement in understanding for participants. This improvement is also evident in areas that are directly relevant to life sciences companies as shown in Figure 3-6. For example, the improvement shown for medical reimbursement—a key revenue concern in life science markets—is especially impressive.

_______________

15Andrew Kurtz, “The NCI SBIR Program: An Overview of New Funding Opportunities and Strategies for Employing Lean Startup Tools to Drive Success in Your Small Business,” AACR presentation, April 20, 2015.

FIGURE 3-5 State of participant knowledge, before and after I-Corps participation.

SOURCE: Andrew Kurtz, “The NCI SBIR Program: An Overview of New Funding Opportunities and Strategies for Employing Lean Startup Tools to Drive Success in Your Small Business,” AACR presentation, April 20, 2015, p. 35.

FIGURE 3-6 Change in life science business understanding after I-Corps participation.

SOURCE: Andrew Kurtz, “The NCI SBIR Program: An Overview of New Funding Opportunities and Strategies for Employing Lean Startup Tools to Drive Success in Your Small Business,” AACR presentation, April 20, 2015, p. 36.

The FY2014 cohort was a pilot. Results such as those described above have led NCI and other ICs to expand the pilot. However, the program currently serves only a small fraction of Phase I companies at NIH, and it is unclear whether there are either plans or resources to expand the program to serve larger numbers.

Phase IIB

This program is designed to provide additional support for development efforts pursued in a previously funded NIH SBIR Phase II, often for grant for products or technologies that require ultimate approval by a Federal regulatory agency.16 Although the amount of funding needed for a trial varies substantially, Phase IIB is not designed to fully fund the process through the end of Phase 3 clinical trials. According to Dr. Matthew Portnoy, the NIH SBIR/STTR Program Director, Phase IIB is designed to get companies close to or to the end of Phase 2 clinical trials (in most cases, Phase 3 is much more expensive).17

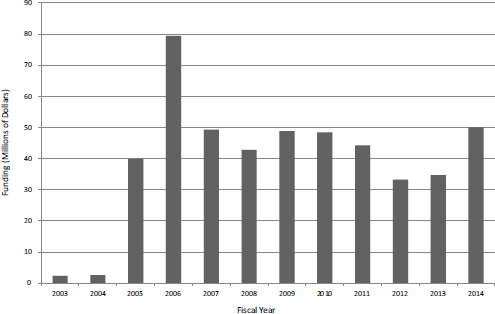

Phase IIB started in FY2003 as a small pilot and as of FY2014 provided about $50 million in funding a year for about 50 projects (see Figure 37).

Data from the 2014 Survey show that the primary purpose of SBIR/STTR Phase IIB—supporting companies partially through clinical trials—is to a considerable extent being achieved. About three-quarters of Phase IIB survey respondents reported that their project required FDA approval (a surprisingly low number given that Phase IIB is supposed to be allocated only to projects that require FDA approval). Table 3-1 shows that Phase IIB companies were more successful in completing Phase 3 clinical trials than were other awardees, and they abandoned the process at a much lower rate.

More than one-third of respondent Phase II companies had abandoned the clinical trials process by the time of the survey; this was true for only 5 percent of respondent Phase IIB companies. Conversely, 10 percent of respondent Phase II and 21 percent of respondent Phase IIB companies had completed the entire clinical trials process. These encouraging numbers suggest that Phase IIB is having a positive impact, although the small numbers tracked through the survey suggest caution in interpreting these results (see Table 3-1).

_______________

16According to the NIH Grants Policy Statement, Revised March 31, 2015, “Some NIH ICs offer Phase II SBIR/STTR awardees the opportunity to apply for Phase IIB Competing Renewal awards. These are available for those projects that require extraordinary time and effort in the R&D phase and may or may not require FDA approval for the development of such projects, including drugs, devices, vaccines, therapeutics, and medical implants related to the mission of the IC.” Access at <http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/nihgps/HTML5/section_18/18.5_small_business_innovation_research_and_small_business_technology_transfer_programs.htm>.

17Discussion with Dr. Matthew Portnoy, NIH SBIR/STTR Program Director, June 17, 2015.

FIGURE 3-7 Phase IIB funding at NIH, FY2003-2014.

SOURCE: Based on data from National Institutes of Health.

TABLE 3-1 Phase IIB and Clinical Trials

| Percentage of Respondents | ||||

| NIH Total | SBIR Awardees | STTR Awardees | Phase IIB Awardees | |

| Process abandoned | 35.5 | 35.9 | 33.3 | 5.3 |

| Preparation under way for clinical trials | 34.4 | 35.5 | 28.2 | 47.4 |

| IND granted | 4.7 | 4.1 | 7.7 | 10.5 |

| In Phase 1 clinical trials | 4.7 | 5.1 | 2.6 | |

| In Phase 2 clinical trials | 9.4 | 7.4 | 20.5 | 15.8 |

| In Phase 3 clinical trials | 2.3 | 1.8 | 5.1 | |

| Completed clinical trials | 9.0 | 10.1 | 2.6 | 21.1 |

| BASE: NIH PROJECTS REQUIRING FDA APPROVAL |

256 | 217 | 39 | 19 |

NOTE: If the large portion of awardees who were not able to be reached by the survey contained a large percentage of companies that went out of business because they could not proceed with FDA approval, the survey results may understate the number of those requiring FDA approval and the percentage who did not proceed with FDA approval.

SOURCE: 2014 Survey, Question 41.

BOX 3-2

Award Size Rules for SBIR/STTR

After the 2011 reauthorization, 15 U.S.C. §138 raises the basic limits on award sizes to $150,000 and $1 million for Phase I and Phase II, respectively. The agencies are allowed to go 50 percent higher (to $225,000 and $1.5 million) without authorization from SBA. SBA may issue waivers to go higher than the upper limits on specific topics. As of September 2013, NIH had received six waivers approved by SBA, five for specific topics and one for the HHS/NIH Annual Omnibus SBIR and STTR solicitations. SBA granted the waiver under the following conditions:

- NIH may allocate no more than 5 percent of its SBIR funds to fund the portion of SBIR awards (Phase I and Phase II) that exceed the guidelines.

- NIH may allocate no more than 5 percent of its STTR funds to fund the portion of STTR awards (Phase I and Phase II) that exceed the guidelines.

- Based on the SBIR and STTR Policy Directives, NIH may also use non-SBIR funds to fund the portion of SBIR awards that exceed the SBIR guidelines, and may use non-STTR funds to fund the portion of STTR awards that exceeds the STTR guidelines.

SOURCE: Gregory A. Davis, Karen D. Gordon, Ellory E. Matzner, and Daniel E. Basco, “Preliminary Evaluation of Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Program Limits on Award Size at the National Institutes of Health,” Science and Technology Policy Institute memo, September 9, 2013.

Extra-large Awards

NIH is well known in the SBIR community for providing awards that are larger than those set forth in SBA guidelines (see Box 3-2 for size rules). Such awards are permitted under waivers received from SBA. In September 2013, the Science and Technology Policy Institute (STPI) provided an initial report to the White House Officer of Science and Technology Policy on over-sized awards at NIH.18 The STPI report focused primarily on the rationale for larger awards. Key findings from the study include the following:

- Biomedical research is expensive (see the Tufts study noted above).

- The cost of drug development has doubled about every 9 years since 1950.

- Venture funding in life sciences has moved downstream, reducing the funding available for early-stage companies.

_______________

18Gregory A. David, Karen D. Gordon, Ellory E. Matzner, and Daniel E. Basco, “Preliminary Evaluation of Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Program Limits on Award Size at the National Institutes of Health,” Science and Technology Policy Institute memo, September 9, 2013.

TABLE 3-2 Extra-large Awards at NIH, FY2009-2012

| Rank by size | Company Name | Award Years | Total Award Dollars |

| 1 | ADVANTAGENE, INC | 3 | $5,293,474 |

| 2 | LENTIGEN CORPORATION | 3 | $5,082,389 |

| 3 | VISTAGEN THERAPEUTICS, INC. | 3 | $4,604,082 |

| 4 | SELEXYS PHARMACEUTICALS CORPORATION | 3 | $4,380,425 |

| 5 | TRANSCENDENT INTERNATIONAL LLC | 3 | $4,228,802 |

| 6 | OMNIOX, INC. | 4 | $3,978,944 |

| 7 | SANARIA, INC. | 4 | $3,963,532 |

| 8 | AUTOMMUNE TECHNOLOGIES, LLC | 3 | $3,938,686 |

| 9 | MICROTRANSPONDER, INC | 7 | $3,828,360 |

| 10 | CIRCULITE, INC. | 3 | $3,785,688 |

| 11 | LYCEAN TECHNOLOGIES, INC. | 2 | $3,756,977 |

| 12 | PHARMACOGENETICS DIAGNOSTIC LABORATORIES | 4 | $3,653,414 |

| 13 | INVIVO SCIENCES, LLC | 4 | $3,647,125 |

| 14 | SIGNUM BIOSCIENCES | 4 | $3,620,902 |

| 15 | REGENEREX, LLC | 2 | $3,588,048 |

| 16 | ADVANCED CELL DIAGNOSTICS INC. | 4 | $3,530,276 |

| 17 | GEL-DEL TECHNOLOGIES | 3 | $3,492,034 |

| 18 | ANGION BIOMEDICA | 3 | $3,491,534 |

| 19 | AMBERGEN, INC. | 4 | $3,468,150 |

| 20 | ETUBICS CORPORATION | 3 | $3,353,817 |

| 21 | STRATATECH CORPORATION | 3 | $3,312,268 |

| 22 | ARIETIS | 4 | $3,265,574 |

| 23 | GLYSENS, INC. | 4 | $3,228,959 |

SOURCE: Gregory A. Davis, Karen D. Gordon, Ellory E. Matzner, and Daniel E. Basco, “Preliminary Evaluation of Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Program Limits on Award Size at the National Institutes of Health,” Science and Technology Policy Institute memo, September 9, 2013, pp. B-1–B-2.

- Unlike the Department of Defense, there is no rationale for NIH to provide non-SBIR funds to further develop promising ideas.19

The STPI report also provided some useful data about the incidence of extra-large awards, focused on FY2009-2012. Table 3-2 shows the 23 awards

_______________

19Ibid., pp. iii-iv.

identified by STPI as exceeding the maximum total allowed under reauthorization ($3.25 million).

The STPI report concludes that the amounts provided are appropriate in the context of rising costs and that they are sufficiently rare (8 percent of awards) that they do not undermine program requirements to provide funding for a wide range of companies.

A review of the STPI report does, however, raise some further questions. The current maximum total allowed of $3.25 million has been the case only since FY2013. Applying current benchmarks retrospectively seems inappropriate. In addition, the program has been providing extra-large awards for many years, but the STPI review was limited to FY2009-2013.

Perhaps more importantly, though, the STPI report does not address the key question: what did NIH get for the additional funds? Are larger awards necessarily associated with better outcomes? If not, then it is difficult to make a case for them. There is also a related question: because review panels do not weigh the proposed budgets for projects against each other, there may be an inherent bias within the application process that links better scores to more ambitious/more expensive projects.

Extra-large Awards: Data from Agency Records

The STPI report focuses only on a narrow definition and time frame. It may be more useful—and providing of better context—to use a different set of metrics and a longer time frame.

STPI defines extra-large awards as those that provide total funding of over $3.25 million. However, it is difficult to define a “project” when there is often substantial overlap between different awards—companies often receive multiple awards for the development of technologies that are closely related to each other. Therefore, it is useful to focus this analysis specifically on the size of individual SBIR/STTR Phase II awards. It is acknowledged that some Phase I awards are also extra-large, but the financial impact of these awards on the program as a whole is much less than that of Phase II awards, which are on average an order of magnitude larger than Phase I. Using data provided by NIH for FY2001-2014 provides a more extended view of patterns of extra-large awards. Excluding from the analysis Phase IIB awards, which are designed for a specific purpose and are by definition larger than standard Phase II awards, as well as supplementary awards, also helps focus on Phase II awards. The data have been cross-checked against data submitted to SBA by NIH and available from the SBA website.

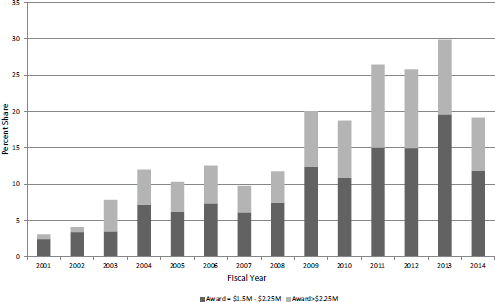

Overall, the number of larger awards grew steadily from FY2001 to FY2011. At about the time of the 2011 reauthorization of the SBIR/STTR programs, when new limits were imposed and blanket agency level waivers were no longer permitted, the number of larger awards stopped growing and, in 2014, dropped 24 percent. Table 3-3 shows awards over $1.5 million during the period FY2001-2014.

TABLE 3-3 NIH Phase II Awards of More than $1.5 million, FY2001-2014

| Fiscal Year | SBIR | STTR | Total | |||

| Number of Awards | Amount of Funding (Dollars) | Number of Awards | Amount of Funding (Dollars) | Number of Awards | Amount of Funding (Dollars) | |

| 2001 | 14 | 30,478,132 | 14 | 30,478,132 | ||

| 2002 | 17 | 32,303,153 | 1 | 2,073,798 | 18 | 34,376,951 |

| 2003 | 35 | 95,717,136 | 1 | 1,846,876 | 36 | 97,564,012 |

| 2004 | 50 | 121,764,850 | 5 | 11,802,203 | 55 | 133,567,053 |

| 2005 | 39 | 95,651,702 | 6 | 11,872,663 | 45 | 107,524,365 |

| 2006 | 54 | 128,836,919 | 4 | 9,724,432 | 58 | 138,561,351 |

| 2007 | 34 | 74,395,458 | 6 | 11,739,773 | 40 | 86,135,231 |

| 2008 | 46 | 101,489,214 | 6 | 12,856,978 | 52 | 114,346,192 |

| 2009 | 79 | 181,126,549 | 2 | 3,354,070 | 81 | 184,480,619 |

| 2010 | 65 | 145,922,317 | 11 | 25,015,316 | 76 | 170,937,633 |

| 2011 | 86 | 192,849,665 | 9 | 22,215,213 | 95 | 215,064,878 |

| 2012 | 84 | 190,537,470 | 11 | 23,462,720 | 95 | 214,000,190 |

| 2013 | 93 | 205,117,540 | 3 | 5,798,604 | 96 | 210,916,144 |

| 2014 | 64 | 141,686,526 | 9 | 18,637,007 | 73 | 160,323,533 |

| Total | 760 | 1,737,876,631 | 74 | 160,399,653 | 834 | 1,898,276,284 |

SOURCE: Based on data from the National Institutes of Health.

The steady growth trend in both larger awards and their associated funding should be put in context. Table 3-4 shows these larger Phase II awards as a percentage of total awards and funding for Phase II during this period. The share of awards of $1.5 million or more increased from 3.1 percent of the total in FY2001 to 29.9 percent in FY2013, before declining to 19.2 percent in FY2014. The growth in funding shares was even greater, from 8.8 percent in FY2001 to 50.6 percent in FY2013, before declining to 33.3 percent in FY2014. These data suggest that the limits imposed under reauthorization have already had an impact.

Some awards are, however, considerably larger than the average. Table 3-5 shows the number of awards and associated funding for awards that are more than $2.25 million. The data for extralarge awards largely track with those for larger awards in general. Both the number of awards and their funding peaked in FY2011-2012, and have since declined. It is worth noting that these extra-large awards became possible quite suddenly in FY2003.

Overall, Figure 3-8 shows both the steady growth in importance of large awards within the SBIR/STTR programs and also the impact of the new limits.

TABLE 3-4 NIH Phase II Awards of More than $1.5 million as a Percentage of All Awards and Funding, FY2001-2014

| Fiscal Year | SBIR | STTR | Total | |||

| Percentage of All Awards | Percentage of All Funding | Percentage of All Awards | Percentage of All Funding | Percentage of All Awards | Percentage of All Funding | |

| 2001 | 3.3 | 9.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 8.8 |

| 2002 | 4.1 | 9.9 | 3.3 | 9.9 | 4.1 | 9.9 |

| 2003 | 8.0 | 24.6 | 4.2 | 13.4 | 7.8 | 24.2 |

| 2004 | 12.3 | 31.5 | 9.3 | 27.9 | 12.0 | 31.2 |

| 2005 | 10.2 | 23.9 | 11.3 | 26.1 | 10.3 | 24.1 |

| 2006 | 13.0 | 27.7 | 8.7 | 24.9 | 12.6 | 27.4 |

| 2007 | 9.6 | 20.8 | 11.1 | 23.1 | 9.8 | 21.1 |

| 2008 | 11.9 | 25.6 | 11.1 | 23.4 | 11.8 | 25.3 |

| 2009 | 21.9 | 41.2 | 4.7 | 9.0 | 20.0 | 38.7 |

| 2010 | 18.2 | 36.2 | 22.9 | 47.7 | 18.8 | 37.5 |

| 2011 | 27.7 | 46.3 | 18.8 | 37.6 | 26.5 | 45.2 |

| 2012 | 25.9 | 46.1 | 25.0 | 48.8 | 25.8 | 46.4 |

| 2013 | 33.2 | 53.9 | 7.3 | 15.9 | 29.9 | 50.6 |

| 2014 | 19.2 | 33.5 | 18.8 | 32.4 | 19.2 | 33.3 |

| Total | 14.7 | 31.4 | 12.0 | 27.9 | 14.4 | 31.1 |

SOURCE: Based on data from the National Institutes of Health.

Outcomes from Larger Awards

The 2014 survey can be used, at least on a preliminary basis, to examine the relationships between award size and outcomes, as well as NIH selection scoring and outcomes. The latter is discussed in Chapter 4 (Quantitative Outcomes).

During the 14 years covered by this analysis, awards in excess of $1.5 million cost a total of $1.9 billion, which is 31 percent of the total spending on Phase II awards (excluding Phase IIB and supplementary awards). The marginal cost—the cost over and above that incurred had these awards been set at $1.5 million—was $647 million. Given that the average award size across this period was $864,000, this funding could have provided an additional 749 standard-sized awards—or an increase of about 13 percent in the number of Phase II awards. So the question is whether NIH received good value for these investments. In reality, funding additional awards would likely have meant funding weaker applications, as acceptance moved farther down the list of fundable applications. Therefore, it is

TABLE 3-5 NIH Phase II Awards of More than $2.25 million, FY2001-2014

| Fiscal Year | SBIR | STTR | Total | |||

| Number of Awards | Amount of Funding (Dollars) | Number of Awards | Amount of Funding (Dollars) | Number of Awards | Amount of Funding (Dollars) | |

| 2001 | 3 | 11,614,499 | 3 | 11,614,499 | ||

| 2002 | 3 | 7,584,883 | 3 | 7,584,883 | ||

| 2003 | 20 | 68,656,403 | 20 | 68,656,403 | ||

| 2004 | 19 | 65,090,916 | 3 | 7,855,839 | 22 | 72,946,755 |

| 2005 | 17 | 55,821,258 | 1 | 2,623,076 | 18 | 58,444,334 |

| 2006 | 23 | 72,500,887 | 1 | 3,983,527 | 24 | 76,484,414 |

| 2007 | 14 | 38,945,205 | 1 | 2,657,177 | 15 | 41,602,382 |

| 2008 | 17 | 48,632,474 | 2 | 5,292,673 | 19 | 53,925,147 |

| 2009 | 31 | 95,419,468 | 31 | 95,419,468 | ||

| 2010 | 26 | 74,351,334 | 6 | 16,220,796 | 32 | 90,572,130 |

| 2011 | 37 | 105,817,941 | 4 | 12,120,122 | 41 | 117,938,063 |

| 2012 | 36 | 105,014,427 | 4 | 11,209,092 | 40 | 116,223,519 |

| 2013 | 32 | 94,170,229 | 1 | 2,561,843 | 33 | 96,732,072 |

| 2014 | 27 | 77,154,871 | 1 | 2,983,056 | 28 | 80,137,927 |

| Total | 305 | 920,774,795 | 24 | 67,507,201 | 329 | 988,281,996 |

SOURCE: Based on data from the National Institutes of Health.

not likely that the additional awards would have generated a return as high as the average return on the existing portfolio of funded projects.

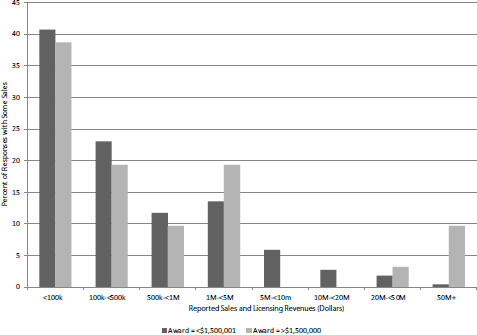

The simplest outcomes to consider are sales revenues and the acquisition of additional investment funding. For this analysis, the outcomes for projects that received $1.5 million or less in SBIR Phase II awards (excluding Phase IIB) and those that received more than $1.5 million are compared. Figure 3-9 shows sales for the 252 respondent companies that reported some sales.

Thirty-one companies reported receipt of larger awards. This number approximately aligns with the percentage of extra-large awards during this period (see agency data section above). This relatively small number means that caution should be employed in interpreting these outcomes. However, it is notable that three of the four projects reporting at least $50 million in related sales received larger awards and that this group accounted for four of the nine projects reporting at least $20 million in sales.

This is only the first review of this issue. We urge that NIH reproduce and extend this analysis using data as they become available. However, the results do

FIGURE 3-8 Share of large and extra-large awards in all NIH SBIR/STTR funding for Phase II (excluding Phase IIB), FY2001-2014.

SOURCE: Based on data from the National Institutes of Health.

FIGURE 3-9 Sales reported for standard and extra-large projects, by range, FY2001-2010.

SOURCE: Based on NIH awards data and 2014 Survey (N=221 [<$1,500,001] and N=31 [>$1,500,000]).

suggest that even though there is little difference in outcomes for most awards, the large award companies generated more of the largest reported outcomes than their share of all awards would lead us to expect.