7

Ebola and Acute Disruptions

Janna Patterson, Senior Program Officer at The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, stressed that the examination of acute disruptions from multiple perspectives highlights dimensions to the human complexities that may not be evident in quantitative data. Patterson stated that while the quantitative data are essential for setting priorities when allocating human and financial resources, she emphasized how important it is to be acutely aware of children’s needs during times of emergencies. She illustrated her point by sharing a vignette of a newborn girl during the height of the Ebola crisis in Liberia where there were no clear protocols in place amid the circumstances of her mother’s untimely death. Patterson questioned, in a country devastated by a terrible disease, where the fear of it was pervasive, what do you do with the most vulnerable? In this instance, the most vulnerable being an infant born to a mother who would die of Ebola only hours after giving birth. The discussions that followed, at Patterson’s urging, grounded the conversation in the full range of complex issues that the vignette highlighted as a way to move the conversation beyond child survival to thriving and also looking toward the future.

ADVERSITY AND RESILIENCE IN YOUNG CHILDREN FROM SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA

Theresa Betancourt, Director of the Research Program on Children and Global Adversity at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, presented her work on adversity, resilience, child mental health, and

development, drawing from recent case studies in Rwanda and a 13-year longitudinal study in Sierra Leone. Using mixed methods approaches that moved from observational research to effectiveness studies and implementation science, Betancourt showcased two research programs on children in adversity that sought to identify factors and processes that contributed to risk and resilience in children, families, and communities facing such adversity globally.

The goal of this work is to focus on capacities and not just deficits, in order to develop ways to close the gap between what is known about children in adversity and toxic stress and the quality of investments in terms of what is actually done on the ground.

Betancourt chronicled Sierra Leone’s 11-year civil war by highlighting the resulting outcomes in terms of population displacement and integration of children into armed forces and armed groups, where there have been deliberate attempts by rebel groups to sever ties between young people and their communities. Betancourt’s longitudinal study began as the civil war was ending and sought to identify risks and protective processes in children’s psychosocial adjustment and community reintegration to inform programs and policy.

Betancourt and her team began their work with qualitative studies to glean information on how individuals think about constructs related to parenting, risk, resilience, and child mental health and development given the context in Sierra Leone (Betancourt, 2010; Betancourt et al., 2010a,b,c, 2011, 2013). The data from this process were used to inform the development of measures to assess these constructs. This work involved the adaptation of existing measures as well as the creation and validation of new measures, which subsequently informed intervention models. This process of gathering contextually relevant information from the community informed the development of a set of interventions. The interventions were then tested using randomized controlled trials.

Betancourt noted that the longitudinal aspect of the study made it possible to find the original study participants and assess the intergenerational effects of violence on this population. This process involved multiple partners across government ministries, universities, and a local team. Results of the study revealed that those who continue to have the poorest outcomes today are experiencing an accumulation of war-related toxic stress exposures but also difficulties and additional stressors in the post-conflict environment of Sierra Leone. Especially poignant are ongoing issues related to stigma, which prohibits young people from performing well in school, being able to hold a job, and maintaining interpersonal relationships.

Because of a dearth of mental health professionals in Sierra Leone, Betancourt stated that the intervention model utilized the collectivist

culture, where young people in groups were solicited. Because depression and traumatic stress reactions frequently co-occur in this setting, Betancourt argued that the key was to design cross-cutting interventions where a mental health program would be linked to education, employment, and other life opportunities. The program was designed so it could go to scale and be implemented by partners locally in a way that is ethical and safe for the youth. Findings with 436 youth showed significant effects on improved emotion regulation, interpersonal skills, social support, and also reduced functional impairment (Betancourt et al., 2014a).

Shifting to Rwanda, where there is high population density and a significant percentage of the population under age 18, Betancourt’s work studies the effects of compounded adversities such as trauma, chronic illness, and poverty on children and families. Rwanda is a context impacted by multiple adversities, including the effects of the 1994 genocide and the AIDS epidemic.

Working in partnership with Partners In Health in Rwinkwavu, a case-control study (Betancourt et al., 2014b) investigated mental health and protective factors in children across three groups: those who were HIV positive, children who were affected because a caregiver was living with HIV, and unaffected children. Finding depression and mental health issues in both the HIV positive and HIV-affected children compared to the unaffected, Betancourt’s team sought to build interventions based on existing resources at the individual, family, and community levels. The objective was to empower caregivers and did so by drawing on Rwandan culture and proverbs.

A subsequent study focused on 82 families, where half were randomized to the family strengthening home visiting intervention and half to usual social work services (Betancourt et al., 2014c; Under review). This group comprised 170 children and 123 caregivers; half of the group consisted of single caregiver households. Betancourt noted that the Family Strengthening Intervention (FSI) was utilized because it focused on enhancing resilience and communication among families managing stressors due to parental chronic illness. The intervention helped families establish a narrative, given a number of genocide survivors in the families, by drawing on existing strengths and supports while also seeking to improve parenting skills, parent–child relationships, and communication skills. Betancourt stated that a family home visitor also helped families navigate support services for school, health insurance programs, and informal resources and supports in the community.

Betancourt reported that impacts of the intervention were seen in improvements in mental health. In particular, the FSI was associated with reduced depression in children. Additionally, Betancourt emphasized that caregiver outcomes revealed significant improvements in social

support for the single caregivers, and for dual-caregiver households at the 3-month follow up. The results revealed the intervention group used less alcohol and reported reductions in intimate partner violence.

Betancourt concluded by making a call to move from observational studies to intervention development and evaluation while keeping attention turned to implementation science. In doing so, Betancourt noted that the types of programs she presented will likely work at scale. Alternate delivery platforms will be critical to this process, Betancourt maintained. For example, the educational and youth employment platforms can be employed to reach youth as well as young children and their caregivers through the social protection system.

Betancourt concluded by stating that efforts being led by local governments and local actors and stakeholders require collaboration to arrive at a point of sustainability. Betancourt said that through integrated responses, times of crisis provide an opportunity to “build back better” for children.

THE EPIDEMIOLOGY OF EBOLA

Taha Taha, Professor of Epidemiology and Population, Family and Reproductive Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, provided an epidemiological perspective of the impacts of acute disruptions on children and their caregivers. He did so by illustrating how a single infectious disease such as Ebola virus disease (EVD) leads to an acute disruption for states and systems, but also to individual communities and the children in those communities.

The first EVD outbreak occurred in 1976 between Sudan and Zaire (present day Democratic Republic of the Congo). The average case fatality rate for EVD is 50 percent, but Taha noted that it can be as high as 90 percent and as low as 20 percent (WHO, 2015). Taha presented the progression of outbreaks since the first outbreak in 1976, with associative case and mortality data. Taha also presented a hypothesis that explains how EVD moved from the remote jungles of Central Africa to West Africa in the most recent EVD outbreak. The hypothesis he presented indicates that Ebola has always been in West Africa and misclassified as Lassa fever. Taha noted that genetic sequencing on the most recent outbreak revealed 97 percent homogeneity between the strain detected in West Africa and present in Central Africa since the 1970s (Gire et al., 2014; Vogel, 2014).

Taha remarked that questions remain as to whether the outbreak in West Africa could be linked to some of the structural factors that exist in the region. Each of Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone were all recovering from civil war during the onset of the most recent outbreak. Taha said that collectively, weak infrastructure, demographic factors, and the prolonged

civil wars have also been hypothesized to be the cause of the recent West Africa EVD outbreak.

Exploring the reservoir, vector, and host relationship in EVD, Taha noted primates may be an intermediary host, but he also stated more recent evidence suggests bats are the primary hosts, because historically bats were present in large numbers when an outbreak was discovered. In the most recent outbreak, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention isolated Marburg, which is a virus carried by bats. Central to understanding the dynamic between viruses and humans, Taha noted, is that there must be a disturbance to the equilibrium—certain human and ecological factors—that cause the virus to emerge, which has been the case for EVD.

In terms of EVD transmission, Taha pointed out that there are two settings that are important: the community setting and the clinical setting. The virus is transmitted from wild animals to humans through close contact, which Taha emphasized “close” to mean contact with bodily fluids. He emphasized that every bodily fluid is not only infectious but highly infectious. These include blood, urine, breast milk, and semen. Taha continued by stating EVD is not airborne because the virus exists only in bodily fluids and is unlikely to be aerosolized or transmitted through dust particles. EVD spreads in human populations through human-to-human transmission through direct contact with infected secretions or organs. Thus, hospitals become a source of transmission and Taha stressed that patients and relatives in the clinical setting amplify the transmission.

The rate for secondary cases from a single case of EVD is two to three cases, in that every single case of Ebola will likely lead to a generation of two or three (Chowell and Nishiura, 2014), stated Taha. By comparison, a single case of measles will lead to 15 or 17 additional cases. The most recent EVD outbreak resulted from a single unspecified animal reservoir to human transmission event in Guinea (see Box 7-1). As the outbreak spread to clusters of cases throughout the three interlocking countries of

West Africa, high population movement was one of the critical factors that contributed to the dynamics of transmission that occurred.

EVD and its aftereffects disproportionately touched the lives of children and women. Post-Ebola impacts were quite pronounced in the number of orphans that resulted, which Taha said was 9,600 by February 2015 (Evans and Popova, 2015). In addition, more women were infected than men, with 56 percent of reported deaths being female (Wolfe, 2014). The fact that women typically care for the sick was the reason Taha cited for these gender-specific mortality rates.

Among survivors, there are a number of clinical complications, including impacts on the eyes, brain, kidneys, liver, joints, in addition to certain chronic clinical complications that are just now surfacing, stated Taha. Taha also pointed out the concern that survivors may be carrying the virus that might have created a reservoir within survivors much like HIV in that it will never disappear, but will remain in a latent phase.

Taha argued that in EVD transmission, the context—including individuals and communities—is a determinant in the outbreak. According to Taha, factors that contributed to making the recent EVD outbreak the most deadly in history include inadequate health care infrastructure; ineffective containment protocols and poor burial practices; contextual factors such as mobile populations in dense urban settings; poor coordination and dis-empowered local leadership; and community factors, including engagement, which he argued is crucial to successfully controlling outbreaks. Moreover, disruptions in health care led to complications and increased susceptibility to other infectious diseases, noted Taha. For example, it was reported that childhood immunization programs were affected as a result of the outbreak.

LESSONS LEARNED TOWARD BUILDING RESILIENCE

Janice Cooper, Country Lead of the Liberia Mental Health Initiative at the Carter Center, provided her perspective on service delivery after the recent EVD outbreak, particularly related to mental health and disabilities, where in Liberia there are few trained mental health providers. Cooper was at the frontlines of the Ebola crisis as the country representative to the Liberia Mental Health Initiative of the Carter Center, which had three initiatives in Liberia involved in the Ebola response (see Box 7-2).

Cooper laid the foundation for the EVD outbreak by presenting some of the challenges in systems that supported young children in Liberia prior to the outbreak. Generally, Liberia could be characterized as having high rates of poverty and malnutrition, with poor health outcomes. Prior to the EVD outbreak, for children under 5, child mortality rates were 94/1,000 (LISGIS et al., 2008). Of the children under age 5 who died, 60

percent of these deaths occurred within the first 2 years (LISGIS et al., 2008). Data from 2013 revealed 32 percent of children under 5 in Liberia experienced stunting (LISGIS et al., 2008). Among 3–4-year-olds, the prevalence of stunting was 42 percent (LISGIS et al., 2008). Immunization rates and birth registration rates were also very low. Only 48 percent of children were fully immunized by 12 months, 34 percent between 1–2 years, and 40 percent of all 1–5-year-olds had all their basic immunizations (LISGIS et al., 2008). One-quarter of all births were registered (LISGIS et al., 2008). In terms of maternal health, Liberia has high maternal death rates. Maternal mortality accounted for 40 percent of all deaths to women of childbearing age and at 1,072/100,000 is among the highest in the world (LISGIS et al., 2008). More than 95 percent of live births were to mothers who received prenatal care, however, even in these cases only 56 percent were at health facilities (LISGIS et al., 2008). Skilled birth attendants participated in

more than 60 percent of live births (an increase from 46 percent in a 2007 survey) (LISGIS et al., 2008). Traditional midwives assisted in 76 percent of non-facility-based care deliveries (LISGIS et al., 2008). Despite low literacy and education rates among mothers, 62 percent received vitamin A post-partum and prenatally, 21 percent had access to iron, and 58 percent of mothers in Liberia had access to deworming prior to birth (LISGIS et al., 2008). Among children, 6 months to 5 years, 58 percent had access to deworming. Yet access to nutrition that met infant and young child feeding guidelines proved challenging. While 83 percent of young children 6–23 months received breast milk and breast milk substitutes, only 11 percent had a well-rounded diet and only 30 percent had food the number of times per day by age consistent with international nutritional guidelines (LISGIS et al., 2008).

In addition, Cooper pointed to challenges in access to clean water and quality education. According to Cooper, water and sanitation issues were quite prevalent in Liberia prior to the EVD outbreak, where open defecation remains a problem, as does access to safe drinking water. In terms of access to quality education, Liberia continues to have some of the lowest numbers of qualified teachers in sub-Saharan Africa, and only 35 percent of eligible children attend primary school (World Bank et al., 2013). Furthermore, there is heavy reliance on donor support for education. For children who are enrolled, there is a misalignment in terms of children in age-appropriate grade levels (World Bank et al., 2013).

Cooper made reference to President Sirleaf of Liberia shepherding the passage of the Children’s Law of Liberia based on the Convention on the Rights of the Child in 2011. Despite this, a Save the Children survey found only 30 percent of caregivers were aware that laws existed to protect children and even fewer (15 percent) knew Liberia had a Children’s Law (Ruiz-Casares, 2011). Moreover, there was a high proportion of children living outside the home (54 percent) at one point in a child’s life, with 12 percent before age 14 (Ruiz-Casares, 2011). The information above outlines many of the challenges and shortcomings of the services and programs for young children in Liberia prior to the outbreak and the implications these problems had for children during the response phase.

Shifting to child-specific data surrounding the EVD outbreak in Liberia, Cooper presented a number of figures, noting that they had not yet been disaggregated by age (see Box 7-3). Cooper reflected on the many actors involved in the response and that the coordination required to care for the needs of children—both infected and impacted by Ebola—was complex. The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Save the Children, Plan International, SOS Children’s Villages, THINK, and Child-Fund were the main actors involved in the EVD response that specifically addressed children’s needs. The National Psychosocial Subcommittee was

instrumental in supporting affected families and children, particularly helping families and communities understand the disease, which was important when an entire community would have to be quarantined. The quality of care delivered in Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs) drew heavily from protocols established for HIV to ensure individuals understood that they needed both pre- and post-test counseling.

Child care facilities, called interim care centers (ICCs), were set up during the response to care for the specific needs of children who had been in contact but did not have Ebola, and their parents or caregivers were admitted to treatment units. There were five facilities for children who were affected and unaccompanied in Liberia—with four units for children of all ages and one specific to children from birth to age 5. Transit centers were also critical for those children who may have been leaving an ETU or about to enter an ICC and needed a place to stay during times of curfew and compounded by long travel distances back to communities. There was one transit center, called a transitional home. Trained EVD survivors were among the first to staff the ICCs. There were also specific guidelines developed for how children were taken and also to make sure that there were protocols for journalists and others to take pictures of children.

Coordination among the outside actors and their responses was necessary to ensure this coordination came with commitment, stressed Cooper. Delivery was complex, and actors could promise something on the ground yet there were logjams in delivery; whereas, other actors were unfamiliar with the terrain and culture in Liberia, making it difficult to actualize commitments. Coordination largely occurred in subcommittees, one of which was focused on child protection and another on creating an EVD survivors network.

Cooper elaborated on some of the collateral damages that were particularly impactful on children during and after the EVD outbreak. Schools closed given the rapid pace of the outbreak, which caused overcrowding in many schools as well as the need to break the chain of transition. There

was poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure within schools—even prior to the outbreak—so the risk of infection was high. The Ministry of Education (MOE), with support from various nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), created a school radio program that aired on stations nationwide. Despite these activities, children, especially young children, were often left unsupervised and unsupported. This became particularly widespread once individuals returned to work and also began to be engaged in the EVD response. Consequently, there was a surge in teenage pregnancy and prenatal care for all pregnant females was often not available (Ekayu, 2015).

Cooper emphasized it was difficult to build the foundation for supporting young children during the emergency response phase. She argued that in the case of Liberia, the EVD outbreak has been used as a leveraging point for charting a more robust course for children in the future. Cooper noted that the Carter Center hopes to work with and build on efforts by other actors working in the early childhood space, such as the Open Society Foundation that worked with the MOE to craft a progressive intersectoral policy on early childhood development (ECD). She also mentioned the current Assistant Minister of Early Childhood Education at the MOE has been a champion for addressing comprehensively the needs of young children.

Liberia initiated an early childhood training framework, working in communities to provide skills-based training for caregivers, parents, and teachers. During the EVD outbreak, there were very few technical experts who worked in early childhood, with even fewer psychologists and psychiatrists. Cooper went on to state there were no disability specialists for working with young children. In addition, mental health frontline workers were not considered in the initial response and once they were seen as necessary to the response phase, Cooper noted it became necessary to draw from other sectors, particularly education.

Some of the most important actors in the response were Ebola survivors. Cooper stressed how important survivors were to the response phase, and she made the case for survivors’ involvement particularly in the mental health response. They were instrumental in combating the stigma and distrust that was pervasive among families and communities during the EVD outbreak.

Cooper reflected on the importance of social trust in the response. Therefore, she pointed out the key role of community leaders, in particular the traditional chiefs and elders in the response phase. In addition, Cooper stated that a priority needs to be placed on strengthening the role of families so that families may be integrated into larger efforts to coordinate a response in the future.

TRANSFORMATION INTO AN EBOLA HOT ZONE

A series of eight publicly accessible videos were assembled by Alex Coutinho, Executive Director of the Infectious Diseases Institute of Makerere University in Uganda, to transform workshop participants into an EVD hot zone to see right up front what life was like through the collective voices of those impacted by Ebola. Coutinho suggested many of the key lessons learned from the EVD epidemic are best highlighted through the voices of those serving on the frontlines. He underscored the impact on children through the series of videos accompanied by available case and mortality data (see Table 7-1).

With more than 4,000 cases, Coutinho emphasized that Ebola clearly had a direct impact on children. There were higher mortality rates in children compared to adults because when children get severely dehydrated they deteriorate much faster, noted Coutinho. Apart from being infected, children were also severely affected by sick parents, caring for dying parents, and becoming orphans after their parents died. Coutinho highlighted the ongoing collateral damages suffered by children across the areas of physical and mental health, social protection, education, and nutrition, particularly the disruption in health services that attend to the needs of children. While schooling resumed, Coutinho warned that the global health community does not yet know what the long-term impact will be on child outcomes, especially nutrition given the lack of agricultural activity in many countries during outbreaks. These examples show the direct and indirect impacts Ebola has on the economy and society of a region.

Despite the challenges, Coutinho pointed out there were many success stories and heroic stories of survival, particularly the vital role children played and the roles they assumed as survivors in otherwise devas-

TABLE 7-1 Ebola Statistics as of July 6, 2015

| Country | Total Cases (suspected, probable, confirmed) | Laboratory Confirmed (%) | Total Deaths (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guinea | 3,744 | 3,287 (88) | 2,498 (67) |

| Sierra Leone | 13,150 | 8,673 (66) | 3,940 (30) |

| Liberia | 10,670 | 3,154 (30) | 4,807 (45) |

| Total | 27,564 | 15,114 (55) | 11,245 (41) |

SOURCE: CDC, 2014.

tated Ebola-impacted communities of West Africa. Coutinho stressed the importance of defining family and community investments so that these investments account for children’s needs when shocks occur to various health, education, social protection, and disaster management systems. The needs of children will remain the same, but it is how the delivery mechanisms function during emergencies that determine how young children and their caregivers will fare during these periods of vulnerability. Answering questions about ways for nations and communities to prepare for outbreaks for the future, Coutinho stressed the importance of translating the lessons into action by coordinating well-meaning international organizations and establishing a chain of command that is grounded in the realities of families and communities.

Coutinho reflected the community was blamed in the beginning for the outbreak. In defense, Coutinho noted that no society in the world wants its dead to be buried without ceremony. He stressed that we all have ceremonies, but it just so happened that the ceremonies in the West African countries put those communities at greater risk. Yet it was communities coming together to be mobilized that finally controlled the EVD epidemic, in concert with other efforts, which is one of the greatest lessons to be gleaned from the Ebola outbreak.

EFFECTIVE TECHNOLOGY APPLICATIONS TO INFECTIOUS DISEASE THREATS

Steve Adler, Chief Information Strategist for IBM’s efforts in the recent EVD outbreak, framed his perspective as an “outsider” insofar as he claimed to be a technologist, businessman, and process oriented rather than a child expert. Adler focused on his involvement with creating open data (see Box 7-4) during the recent Ebola outbreak, but also how to best prepare for future crises and the role open data play in the preparedness and response phases.

Adler helped launch the Africa Open Data Jam in August 2014, which led to a large-scale, open-data collection effort for application toward the

EVD epidemic. His experiences gleaned that open data in this context was a sound solution, but implementation proved to be a challenge, particularly in the cultures and contexts of West Africa. Even talking about technology with people in the Ministry of Information, the Ministry of Health, and the MOE was difficult because in talking about how to even collect data, Adler noted that high-level officials would be too polite to admit they did not understand data collection. Data literacy among the leaders in West Africa was a result of the fact that these leaders had never been schooled in the technology world, stated Adler.

A call center was set up to amass short message service (SMS) messages to collect data on how individuals were reacting to the crisis by way of a feedback loop. Complicating this effort was the fact that there were seven languages used across Sierra Leone alone. In addition, 70 percent of the population in Sierra Leone is illiterate and therefore could not participate in the SMS effort. An alternative solution was implemented, in which individuals could call into a call center and their information was then transcribed and sent out as a message. Adler noted that this is just one example where there was a great idea to integrate data into a solution, but implementing the solution in the context of Sierra Leone was quite challenging.

Adler also worked with actors in Washington, DC, but quickly found that there was not an effective flow of information nor a central repository or database that all participating actors were drawing from to better understand what was happening across the affected countries in West Africa. Adler found that all of the different actors had their own data they were utilizing to try to determine how they would intervene in the outbreak. Referencing the delayed process by which the resources and staffing for ETUs were mobilized by the U.S. government, Adler lamented that when there is a crisis, different actors show up with what they want to give and not necessarily with what is needed. What was clearly needed during the EVD outbreak was information, noted Adler.

Adler organized an Ebola open data jam in New York where Liberian and Sierra Leonean expats living in the metropolitan area participated by scouring the Internet for available public sources of information about the EVD outbreak and then assembled this data in one place where any aid agency could locate and access it. What emerged as a void in the data was how little digital information was available on the capacity of health care in the affected West African countries. While data may exist, they exist on paper that must be photocopied, faxed, or mailed. This process still does not provide sufficient information about capacity. Adler’s efforts resulted in a comprehensive data model to capture a detailed inventory of not only health care capacity in West Africa, but also an inventory of education and infrastructure capacity. Adler reflected it was difficult to determine what

to fix during the most intense moments of the EVD outbreak when there was little information available about what was wrong, much less any coordinated collection of information related to health infrastructure in place to support the outbreak. The 600-member Africa Open Data Group was formed as a result of Adler’s efforts, making it the largest open data group focusing on Africa in the world.

Moving forward, Adler suggested there should be a commitment to investing in the skills to gather necessary information ahead of the next acute disruption that can supersede barriers with language, culture, and literacy. By doing so, the information can stimulate economic growth because it informs the decision-making process. Adler urged all workshop participants to keep the dialogue going with regard to inventorying capacity in countries globally and to also publish the information online in open data forms so that the actors who may respond to the next global outbreak will be able to take advantage of the information in the future.

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR AN INTEGRATED RESPONSE

Arnaud Conchon of UNICEF prefaced his presentation on challenges and opportunities for an integrated response by surmising that discussions from the workshop seem to converge on agreement that integrated interventions are what need to be done for early childhood, because of the complexity of children in situations of acute disruptions. He informed the group that early childhood considerations during times of emergencies is very new, and subsequently the way humanitarian responses are taking place in particular contexts is also very new.

Conchon presented the landscape of the coordination mechanisms in place for children in emergencies across main categories of actors (NGOs, international organizations, United Nations [UN] agencies, and civil societies) using UNICEF’s ECD in Emergencies (2014c) as a frame for his presentation. This document explains the basic principles of children in emergencies, illustrates an overarching vision of what an integrated response for children should resemble, and provides guidance to all sectors to include the needs of children in existing sector-based responses.

Conchon provided a working definition of emergencies, noting that there is no one single definition of emergency situations. The definition he provided is the one used by UNICEF to ensure humanitarian situation and emergencies mean the same and there are three main criteria that define an emergency: (1) a sudden high number of deaths; (2) an incapacity to respond locally, so there is a need for intervention by the international community; and (3) a state-declared state of emergency. Conchon clarified that humanitarian action is defined differently because it encompasses

the pre-emergency phase—or the emergency preparedness, as well as the early recovery that occurs after the emergency, and eventually links to longer-term development. Across these different phases of emergencies there are different actors and donors.

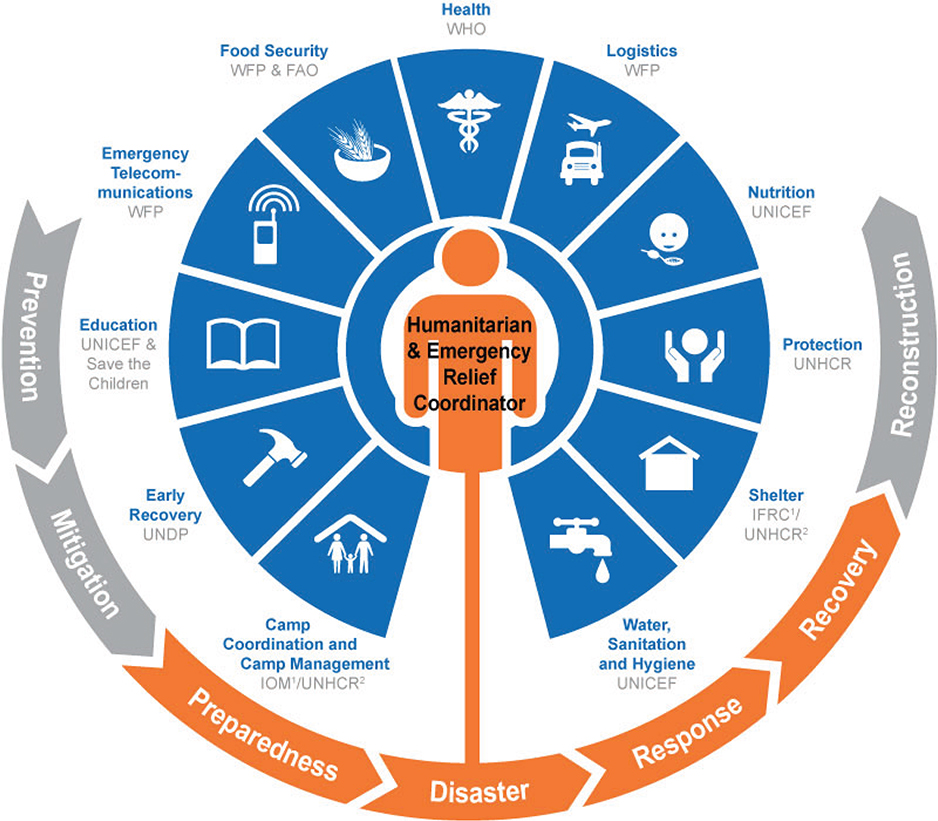

Conchon introduced the UN Cluster System (see Figure 7-1) by way of recounting the increasing range of actors, oftentimes inappropriately matched to the magnitude and scale of needs following emergencies that

NOTE: FAO = Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations; IFRC = International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies; IOM = Institute of Medicine; UNDP = United Nations Development Programme; UNHCR = United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; UNICEF = United Nations Children’s Fund; WFP = United Nations World Food Programme; WHO = World Health Organization.

SOURCE: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 2015.

do not meet the needs of affected children by failing to provide services in any coordinated way—largely because no coordinating mechanism exists. Conchon pointed out that typically in an emergency situation there is a diversity of expertise, mandates, and capacities, but no coordination. Worse, recounts Conchon, is the impact this has on individuals because they become susceptible to answering questions and being assessed by multiple organizations over the span of a very short time, raising expectations of those participating in the inquiries and assessments.

In 2006, John Holmes put into motion the Humanitarian Reform, which included an 11-cluster approach to coordinating emergency response by area of expertise, stated Conchon. The Cluster System evolved since the 2004 Ache tsunami, originally composed of only two clusters with meetings where people share their capacities and their expectations in what they could do to help in a particular emergency context.

Conchon related the Cluster System to children and their particular needs during emergencies. He praised the Cluster System because it allows actors involved in emergency response the ability to identify where the experts within each sector are working. However, the downfall, as Conchon pointed out, is that children fall across all sectors, and this approach is sector based. This model reaches new levels of complexity when the Cluster System also considers the different stages of response from preparedness to reconstruction before, during, and after an emergency. This translates into integrating services specific to children into the emergency programming across time scales. Conchon chose childhood stimulation as an example to illustrate why coordination of services across emergency programming is important for children affected by acute disruptions. Conchon maintained that childhood stimulation does not occur during emergencies because from a clinical perspective during times of emergencies, the supportive tactics that need to be incorporated into the clinical prescriptions usually fall by the wayside. However, Conchon argued it is important to remember that evidence suggests that a stimulated child will have improved growth, increased developmental outcomes, and engage with the mother in ways that are important to long-term outcomes. The benefits of stimulation coupled with nutrition extend beyond the child to decrease the potential for maternal depression.

Conchon used the example of stimulation to explore the benefits of integrated interventions that often do not occur during times of emergencies. He argued that better integration of interventions around the child leads to

- improving the quality of benefits for the whole child,

- minimizing the necessity for needs assessment to occur if needs are already being met,

- increasing the use of common standards and tools,

- promoting a shared vision of children’s needs and priorities,

- promoting inter-agency and intersectoral learning of opportunities,

- increasing response coverage,

- guiding donors funding better,

- informing better decision making,

- providing a foundation for planning for the future,

- ensuring resources are used effectively by reducing duplication of efforts and overlap,

- supporting shared monitoring processes, and

- identifying gaps with greater precision.

How this integration occurs during emergencies was proposed in two ways by Conchon. The first approach is to mainstream children’s needs within the existing sectors of the Cluster System. Conchon pointed out that this may not ultimately have the desired impacts because this approach creates silos of interventions with missed opportunities when individual clusters do not communicate across the 11-cluster system. Instead, Conchon proposed a way forward where services converge on the child’s needs during periods of vulnerability. The difficulty in this approach, Conchon pointed out, is that it requires significant coordination.

The challenges that lie ahead for integrated responses for children during times of emergencies are to overcome the sector-based siloing that all too often occurs and in doing so strengthen the systems, stated Conchon. This strengthening will come by having a vertical response among frontline responders and ensuring the systems are able to support long-term benefits from capacity building put in place during the initial response. The task moving forward, argued Conchon, is to make the needs of children and the corresponding activities already in place visible among the sectors during an emergency. This can be done by creating linkages between locations where services are provided and formal clusters that have subgroups with key actors. By doing so, these linkages point to where certain services can be delivered through each representative sector and highlight a point of contact who can then take responsibility for transferring knowledge and resources between the cluster and the needs of children on the ground.

FRAMING POLICY GUIDELINES FOR CHILDREN IN ACUTE DISRUPTIONS

Zulfiqar Bhutta, Robert Harding Inaugural Chair in Global Child Health and Policy at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, and founding director of the Centre of Excellence in Women and Child Health at

Aga Khan University, laid the foundation for targeted breakout sessions to identify areas of potential policy actions in the context of acute disruptions, which were underscored by Cooper’s and Kuku’s call to have integrated ECD policies in place ahead of any future emergency.

Bhutta underscored the importance of the work of the breakout sessions, stating that at least one-third of the entire global burden of premature child deaths are in geographies where there are either complex situations or major humanitarian emergencies and population displacements (Bhutta and Black, 2014). Bhutta defined the typology of these disruptions in three ways: natural disasters; conflict and population displacement caused by acute conflict; and the impacts of outbreaks or disease conditions. Bhutta pointed toward Ebola as an example of the latter, and a situation in which important lessons can be learned because it reveals the impacts of a broken health system by increasing risks within a population, in addition to how a lack of health system preparedness can impact the perpetuation of some of the problems that emerge because of outbreaks (Iyengar et al., 2015).

Bhutta next turned to the populations at risk and impacted by acute disruptions. He pointed out women and children are among the most vulnerable not only in terms of their exposure to risk, but also because of the effects of the breakdown of health services and health systems that particularly impact this vulnerable population. This vulnerability transfers to the children of women affected as well, multiplying the impact of the disruptions.

Bhutta noted that the breakout groups provide the space to discuss the latest learning from experiences across recent acute disruptions by considering existing guidelines and strategies for children in emergencies as a starting point to perpetuate awareness within those existing strategies of the importance of the protection of women and children and interventions that can promote and protect child development. Bhutta encouraged the breakout groups to move beyond the existing strategies to propose policy guidelines that also identify state actors and actors within the humanitarian response teams that need to consider different time periods, starting from an acute response to stabilization and to restitution of services in the aftermath of such disruptions and disasters.

Finally, Bhutta suggested the groups create guidance on the time-frame of actions and interventions so that as soon as communities move beyond the acute immediate response, states and other actors may begin to put services and systems in place to focus on child survival and also to focus on what could be done to potentially maximize opportunities and gains for children and families who could be living in some of those circumstances for many months to come.

BREAKOUT GROUPS ACROSS DIFFERENT TYPOLOGIES OF ACUTE DISRUPTIONS

Breakout Groups divided among the three types of emergences to each identify three areas for policy guidelines (see Boxes 7-5, 7-6, and 7-7). Workshop breakout groups discussed three areas of focus for ensuring the needs of children are appropriately accounted for during emergencies of different typologies and magnitude that more broadly covered the

preparedness, response, policies, and financing. Individuals from each of the breakout groups across the three different types of emergencies made the following suggestions:

- To empower communities by having integrated preparedness plans in place that specifically consider children’s needs during times of emergencies, including tools and investments to predict the emergency and understand key points for intervention

- To place primacy on community leaders and capacity to ensure an integrated and culturally and child-aligned response phase, and thinking about the response phase in the short term as well as the longer term

- To ensure recovery activities target young children and adolescents anticipating that acute disruptions are often cyclical and this puts in place preventive mechanisms for the future

The policy guidelines considered preparedness, response, and recovery across multiple scales from family, community, national, and international levels.

Some Breakout Group members raised the point that the basic needs of children will stay the same whether a community is in a time of peace, immersed in conflict, or in the throes of an epidemic, but the service delivery mechanism must change to best reach the affected children and what their more specific needs might be during times of acute disruptions. While the time sequence is central to all types of emergencies, some of the Breakout Groups participants deemed it important to highlight the specifics surrounding the different typologies of acute disruptions.

Valerie Bemo, Senior Program Officer responsible for the emergency response portfolio within the Global Development Department at The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, provided some of these key distinctions for workshop participants. She indicated there are key differentiators among the three types of emergencies that need to be considered for particular emergencies surrounding natural disasters, conflict, or outbreaks. The types of responses that need to be considered actually fall under different areas such as response versus prevention and preparation. Bemo elaborated on this topic by type of emergency, stating there are some distinct elements that characterize different types of acute disruptions and these distinctions should be taken into account so that the response appropriately matches the typology of the emergency.

According to Bemo, for human-induced disasters, typically there is a collapse of the state, and thus disruptions to the state’s systems. The response phase cannot always solely count on the government because it is likely part of the conflict. In addition, during a human-induced disaster, there is typically massive movement of people as a result of conflict, turmoil, security issues, and widespread massacre. Disequilibrium then gives way to long-term encampment of displaced individuals.

For rapid onset natural disasters, Bemo indicated the event usually occurs in one place at one moment in time while the slow onset takes place in many days/months. When the rapid onset and threat of one day’s event dissipates, widespread consequences of that event are left in its wake. These span the areas of health, infrastructure, services, and security.

Bemo pointed out outbreaks resemble similar characteristics of a natural disaster, despite the fact that they are often approached from a technical perspective. She emphasized it needs to be understood that an

outbreak is not just a medical issue. There is a human face to outbreaks that can easily get lost in technical conversations.

In addition to these distinct characteristics of emergencies made by Bemo, Adler encouraged workshop participants to consider the confluence of disasters in the future from climate change where there is inherent conflict that will arise from resource scarcity and food security issues. Adler stressed that it will be imperative to apply the lessons learned from previous emergencies to a new type of acute disruptions that will pose a threat in the future in a very changing global climate, including its impact on emotions, politics, and power.

A number of the workshop participants reiterated there has to be systems and policies in place to support children, without which any response to an emergency will fail. Specific to Ebola, Coutinho stressed it is important to take the lessons still coming out of this epidemic and translate them into national structures that bring government and civil society together for emergency response units. Yet, national-level units are often not sufficient.

Cooper emphasized the importance of involving the international community, yet at the same time, recognizing the importance of community engagement and feedback to build community trust. She highlighted the importance of community trust, because the assumption now is that communities place their trust in the hands of their leaders. She warned that if a two-way dialogue does not exist prior to an emergency, it is harder to begin during the emergency.

Masten encouraged workshop participants to think about the interactions between and among certain levels and not to concentrate all preparedness efforts at only one level, whether it is the community level or the national level. She said to build resilience, there needs to be scaffolding in place at different levels, so even when complex organizations of multiple systems break down into pieces in a major disaster, the component systems at each level have the capacity to reorganize and reconnect. Masten stated this becomes a process of integrating capacities and it occurs across all levels of the response phase. The result of this type of preparation is that at the time of an acute disruption, when disaggregation and siloing are likely to occur, there is still the scaffolding in place to protect young children.

Masten concluded her comments by stating, when all of these different systems are taken into account, the questions can be formulated around what do people need to know, what do we need to do to prepare at a family level, a community level, at the school level, at the national level, . . . so that for all levels there is a clear interest in protecting children. In this way the capacity for resilience is distributed throughout multiple systems.

This page intentionally left blank.