8

Past and Future Fiscal Impacts of Immigrants on the Nation

8.1 INTRODUCTION

Chapter 7 described accounting approaches for assessing the fiscal impact of immigration and outlined the conceptual challenges involved in its measurement given that the counterfactual scenario (no immigration) is unobservable. In this chapter, the panel applies these concepts to estimate the fiscal impacts of immigration at the national level. In so doing, the underlying variation across geographic regions that is important for a full understanding of the impacts of immigration is ignored at this point. These national estimates incorporate the U.S. federal government budget in its entirety and a single aggregation of budgets in the 50 states and their localities. Chapter 9 explores variation in state and local fiscal impacts across states in detail.

The panel chose to set geographic variation aside (for the time being) in order to focus on how fiscal impacts of immigrants have changed over time. As described in Chapter 9 and elsewhere in this report, over time there has been considerable change both in states’ fiscal policies and practices and in geographic patterns of immigrant receiving and internal migration. These are important features that mediate impacts on particular geographic regions. But the aggregated national analysis may be more directly useful for national immigration policy, and it provides a feasible method of assessing trends in fiscal impacts over time.

In the sections that follow, the panel first documents the path of net annual fiscal impacts and the relevant characteristics among immigrants and natives during a recent historical period for which good coverage in

annual cross-sectional data exists. Covering 20 years of immigrants’ experiences, from 1994 to 2013, these data allow annual fiscal effects to be decomposed into amounts attributable to different immigrant generations. However, it is important to note that these cross-sectional estimates of fiscal impacts are heavily influenced by the age distribution of the underlying groups at the time of data collection. Thus, although such cross-sectional “snapshots in time” are instructive, they do neglect the evolution of fiscal costs and benefits over time that occurs as these groups age—an evolution that we know to be important (see Chapter 7). After children are born, their average fiscal impacts remain negative for many years because they absorb benefits in the form of public education and other support while paying little or no taxes. But children eventually become adults, many of whom work and, for sustained periods, pay more in taxes than they receive in expenditures on benefits. In old age, the fiscal-impact pendulum typically swings back the other way. To some extent, today’s older immigrants may be taken as proxies for today’s young immigrants observed in future periods. But simply assuming an older age group in a cross section is identical to a younger age group observed at a later time is likely to offer a misleading portrait of the cumulative fiscal impacts of any particular cohort of immigrants over that cohort’s life span.

The above limitation of the cross-sectional analysis establishes the rationale for estimating life-cycle fiscal impacts. The second task undertaken in this chapter is to formalize conjectures about future life-cycle fiscal impacts in a systematic way. The panel presents a longitudinal forecast of the future national fiscal impacts of immigrants arriving today, using updated methodologies developed for the 1997 New Americans report (National Research Council, 1997) and updated data and assumptions about future growth rates, interest rates, and demography. Because the children of immigrants play an important role in the fiscal impact of immigration, we pay special attention to fertility rates and intergenerational patterns of educational attainment, and we factor in return-migration behavior. The forecast aims to answer the following question: In today’s dollars, what is the predicted long-term net benefit to domestic governments of an additional immigrant and that immigrant’s descendants?

8.2 HISTORICAL FISCAL IMPACTS OF IMMIGRATION, 1994-2013

This section provides cross-sectional estimates of the fiscal impact of immigration for the nation at specific points in recent history. These estimates are possible because data essential for this kind of analysis have now been available for an extended period. The addition of questions about parents’ places of birth to the annual demographic supplement to the Current Population Survey (CPS) enabled The New Americans to explore the

current and future fiscal impacts of first and second generation immigrants, which tended to differ significantly (National Research Council, 1997). At that time, only samples for 1994 and 1995 were available with sufficient data fields to identify generational status, so pooling these years to allow for sufficient sample size generated a dataset for a single cross-sectional analysis. With almost two decades of additional data now available, the current panel was able to create a sequence of multiple cross-sectional samples. Thus, we can examine the impacts of immigration, taking into account both the first and second generation, during this historical time interval.

Notes on Measurement

As in the national fiscal projections for the 1997 report, the analyses in this chapter focus on individual immigrants rather than immigrant households (although, when the costs of children are allocated to adults in the same households, as is done much of the time here, a quasi-household structure is created). While many studies of the fiscal impacts of immigration adopt immigrant-headed households as the unit of account, measuring benefits and taxes at the individual level facilitates longitudinal calculations of the type presented in Section 8.3, where the future fiscal impacts of immigration are explored. Households may change their composition over time through marriage and divorce, deaths, births, adoptions, move-ins and move-outs, additions or subtractions of members beyond the nuclear family, and so forth. Also, immigrant-headed households often contain nonimmigrant members. Following individuals is simpler because decision rules for allocating fiscal flows in the face of some of these family-dynamic complications can be avoided.

Within the data analysis approaches used in this chapter, fiscal positives (taxes) and fiscal negatives (expenditures on program benefits) are first allocated to the individuals most closely linked to them. In some cases this individual allocation creates some additional interpretive tasks, relative to household analyses, in order to identify the fiscal impact of a particular population group defined by nativity and generation. The costs of educating the U.S.-born children of immigrants are particularly important in this regard. In a household-based analysis, public education unambiguously creates a cost attributable to the immigrant-headed household. For an individual-based analysis, the cost of public education is detected due to the presence of a child in the household and is initially assigned to that child. In some of the analyses below, we present data in such a way that the age- and individual-specific timing of fiscal impacts (both positives in the form of taxes and negatives in the form of program costs) can be shown—even for children. In other analyses, the fiscal impacts of individuals and their dependents are combined and the impacts of the latter are attributed their parents’ genera-

tional groups. Details about which allocation procedure is used are provided for each of the accounting exercises reported on below.

Age profiles—indicating average flows of taxes or benefits by education, by immigrant generation, and in some cases by time since the immigrant’s arrival—are central to the accounting and forecast methods used here. To generate these profiles, the panel used data from the Annual Social and Economic (March) Supplement of the CPS, which provides annual estimates of program utilization as well information on the characteristics (such as education and nativity) of respondents. These age profiles are used in both the historical static and lifetime forecast analyses presented in this chapter.1 Single-year age profiles were constructed by averaging three adjacent years’ worth of data for smoothness. These age profiles are then rescaled for each middle year so that—when applied to population estimates by age, education, immigrant generation, and time-since-arrival in that middle year—they capture the total flows for a given program in that year in an estimate that is consistent with administrative sources.2 Details

___________________

1 The main alternative to the CPS that could have been used is the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), conducted by the Census Bureau. The CPS and SIPP each have advantages and disadvantages. While ultimately choosing not to use it for other reasons, The New Americans (National Research Council, 1997) panel concluded that the greatest strength of SIPP is that it contains more accurate monthly data on program participation and expenditures and richer information on wealth and income sources than does the March CPS. The current panel, like the panel that authored the 1997 report, chose to use the CPS due its substantially larger sample size. Because the analyses in this report required cells defined by age, immigrant generation, and education, as well as some separate analyses at the state level, sample size was critical. The March CPS also has an oversample of Hispanics (and a number of other groups, including Asians), which increases representation of immigrant and second generation households. In addition, because the March CPS is conducted every year, it is possible to combine across years to further increase the sample size. Moreover, the state-level analysis in Chapter 9 would not have been possible using the SIPP, and the panel felt it was important to use a consistent data source across analyses. Timeliness was also an issue. The lags in release of new SIPP data are much longer than those for the March CPS, which is available in the fall of each survey year. Current immigration research based on SIPP is using the data from the 2008 panel. The immigrant population had a different composition by 2011-2013 relative to 2008—specifically, the more recent period has lower percentages of unauthorized immigrants, fewer Mexican immigrants, and more Asian immigrants. Also, program use and employment change over time. Regarding potential bias, both data sources are known to underreport income and program use. And although internal panel calculations indicated that SIPP shows higher program use than does the CPS, the differences were about the same for immigrants and natives, so the bias was not related to immigrant status but rather just an overall feature of the CPS. Thus, adjustment to administrative totals for income and program use addresses much of the known underreporting problem.

2 The analyses in this chapter make the de facto assumption that immigrants are represented in the CPS roughly proportionally to their representation in the population. For each benefits program, CPS data are adjusted for under- or over-reporting by scaling each record by a single multiplicative factor for that particular program so that the accumulated aggregate over all records match program totals from National Income and Product Accounts. However, there is

about the estimation methods for specific programs are listed in the Technical Annex to this chapter.

To assess the robustness of the panel’s historical estimates, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by varying assumptions about program utilization and about how public expenditures are attributed. We broadly followed the methodology of Dustmann and Frattini (2014), who specified two overarching cost scenarios in which immigrants incur either the average cost or the marginal cost of public goods, plus a number of subscenarios within each of these two. Their baseline specification has immigrants incurring the average cost of public goods. For our analysis, we used the eight scenarios listed in Box 8-1, the first of which is the average-cost baseline, consistent with Dustmann and Frattini (2014).

Dustmann and Frattini (2014) explained the rationale for examining these particular scenarios. In theory, as explained in Chapter 7, pure public goods can be enjoyed by an unlimited number of citizens, implying that the cost of providing them to an additional immigrant should be zero (the marginal cost scenario). But in practice one expects most services provided by governments to be susceptible to congestion. As described in detail in Chapter 7, assigning to immigrants the average cost of public goods—like defense spending, or total defense outlays—calculated across all U.S. residents is a conservative assumption in that it generates estimates that may overstate the net cost of an additional immigrant. Thus, to examine robustness of findings based on the average-cost approach, the panel included scenarios (5 through 8) that assign a marginal cost of zero for public goods, under the assumption that an additional immigrant does not increase the total cost to the nation of services such as national defense.

Scenario 1 includes interest payments as a component of public goods spending, along with defense, foreign aid, and state and local spending

___________________

likely a differential undercount of the unauthorized component of the immigrant population. Based on a residual method that compares survey estimates of the resident population with administrative data on legal immigration, a number of researchers (e.g., Baker and Rytina, 2013; Passel and Cohn, 2014; Warren and Warren, 2013) have estimated the characteristics of the unauthorized population, including its fiscal impacts. These estimates suggest that unauthorized immigrants as a group may have a more positive fiscal impact than authorized immigrants, but only because of their age structure. The average undocumented immigrant is of younger working age than the average documented immigrant (there are very few undocumented immigrants of retirement age); thus, the net fiscal impact of the former is more positive at the federal level and overall. Also, as detailed in Chapter 3, undocumented individuals, young unauthorized immigrants who qualify for the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Program, temporary visa holders, and recent legal permanent residents are ineligible to receive benefits from some programs; and unauthorized immigrants do not qualify for the earned income tax credit. Nonetheless, since, at any given age, unauthorized immigrants tend to earn less than their authorized counterparts, controlling for age, they are less of a benefit to public finances than authorized immigrants.

categories such as subsidies and interest payments. In scenarios 2 and 6, we remove interest payments from the public goods calculation because they represent the cost of servicing debt attributable to past spending and deficits from which new immigrants did not benefit.3 Scenarios 3 and 7 follow The New Americans (National Research Council, 1997) in estimating the consumption of immigrants by assuming a constant real amount of income is remitted to the country of origin and thus not spent in the United States. Based on a conservative reading of a study using data on Germany, Dustmann and Frattini (2014) assumed that immigrants send remittances back to their home countries at levels that affect consumption such that U.S. sales and excise taxes paid by them are reduced by 20 percent relative to the average for the general population. This adjustment factor is used in scenarios 3 and 7 to provide another robustness assessment that is consistent with their methodology. In scenarios 4 and 8, the panel explores

___________________

3 Interest payments, the vast majority of which go to servicing the debt, are not raised right away by an immigrant entering the country—they represent the current cost of servicing past deficits to which new immigrants did not contribute. Over time, an additional immigrant may affect the level of debt and thus debt payments, depending on his or her net fiscal impact. But, particularly for the intergenerational projection exercise (in the second part of this chapter), this calculation would be very complicated as each lifetime profile of marginal fiscal net contribution or cost uniquely affects the debt and debt service costs. Treating the marginal contribution of immigrants to debt service as either zero or average cost as we do provides a range of possible results, although given the impact of discounting on future flows, the true impact would be much closer to the zero cost than the average cost scenario.

the effects from assigning zero capital income taxation to immigrants who have been in the United States for less than 10 years. In the other scenarios, the implicit assumption is that ownership of company shares is distributed similarly across native- and foreign-born populations. But scenarios 4 and 8 assume that recent immigrants do not own shares of U.S. companies and therefore do not make capital tax payments. Although new arrivals do have lower ownership than the general population, this simplifying assumption is clearly an overstatement of the difference in stock equity between natives and immigrants. Nonetheless, it is useful for understanding the potential impact of assumptions about capital ownership by immigrants.

In the sections that follow, the panel first describes the policy environment, and then explores the age structure and number of children of U.S. immigrants, and trends in education, working, and earnings among immigrants. We then examine the effects of variations in patterns of program utilization, receiving government benefits, and paying taxes, by age. Because the assumption about how the costs of public goods are assigned varies across scenarios, our initial analysis of age-related patterns (which follows immediately below) omits them—this allows the discussion to focus first on fiscal impacts linked to age structure. In the subsequent sections, we reintroduce public goods in order to present complete fiscal impact estimates for immigrants and natives for scenario 1 and, to test for robustness, across the other seven scenarios.

A Changing Policy Environment

The New Americans (National Research Council, 1997) was released immediately after passage of welfare reform via the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA). PRWORA was one of the largest changes in fiscal policy in recent decades. The 1997 report attempted to estimate the effects of PRWORA on the fiscal impacts of immigrants, bearing in mind that the law denied certain means-tested benefits to noncitizens. Its authors assumed immigrants received no such transfers until after 5 years of residence.4 The changes in net fiscal impact of immigration associated with PRWORA, although modest, were found to make immigrants less costly to states and localities and more beneficial to federal finances (National Research Council, 1997). Subsequent analyses by Bitler and Hoynes (2013), Borjas (2002), and others indicated that, in the aftermath of PRWORA, participation rates at the national level of immigrants declined for a number of programs relative to those of natives

___________________

4 The affected programs were Supplemental Security Income, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), food stamps (SNAP), nonemergency Medicaid, energy assistance, rent subsidies, and public housing.

(see discussion in Chapter 3). Borjas (2002) found that much of the national decline was attributable to immigrants living in California, who experienced “a precipitous drop in their welfare participation rate (relative to natives).”

In the years since welfare reform, there have been other significant changes to U.S. fiscal policy that likely factor into the fiscal impacts of immigrants. In particular, other income support programs have grown to fill the gaps left by welfare reform. The Earned Income Tax Credit has been expanded several times over the past three decades, rising more than fivefold from an $11 billion program in 1994 to a $58 billion program in 2013. Similarly the child tax credit, introduced in the late 1990s, has grown into a $22 billion program that aims to support working families. Participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), also known as food stamps, declined initially after welfare reform before rising strongly due to policy reforms prior to the Great Recession, during which SNAP participation rates rose even more (Ganong and Liebman, 2013). In 2013, SNAP assistance totaled $75 billion, up from $23 billion in 1994.

Other changes in the federal safety net during this period included the addition of a prescription drug benefit to Medicare starting in 2006, the expansions of Medicaid, and introduction of health insurance subsidies in 2014 via the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which also aimed to rein in future Medicare spending. Undocumented immigrants are explicitly omitted from coverage and subsidies under the ACA, but authorized immigrants are fully eligible. Because the panel’s period of historical data ends in 2013, we do not include the ACA in our historical analysis. In the longitudinal forecast of the future fiscal impacts of immigrants (Section 8.3), we model the effects of the ACA following the assumptions of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).

There were also changes in tax policy during the historical period. Income tax rates were cut across the board in 2001 but partially reinstated for high-income households in 2013. Tax rates on capital gains and dividends were cut in 2003 and were also partially reinstated for high-income households in 2013. By 2011, these tax cuts had reduced average federal tax rates on all income groups, but by more in the lowest four quintiles (Congressional Budget Office, 2014b).

By 2013, most of the federal policy responses to the Great Recession, which significantly lowered taxes and raised spending starting in 2008, had run their course. In particular, payroll tax rates, which were lowered in 2011 and 2012, returned to their precrisis levels. However, usage of means-tested benefits remains elevated compared to prerecession levels (Congressional Budget Office, 2015).

In addition to these changes at the federal level, state and local fiscal policies have also been in flux during the historical period. Chapter 9 provides details about differences across states in the effect of immigration on subnational fiscal situations.

The Age Structure of Immigrant and Native Populations

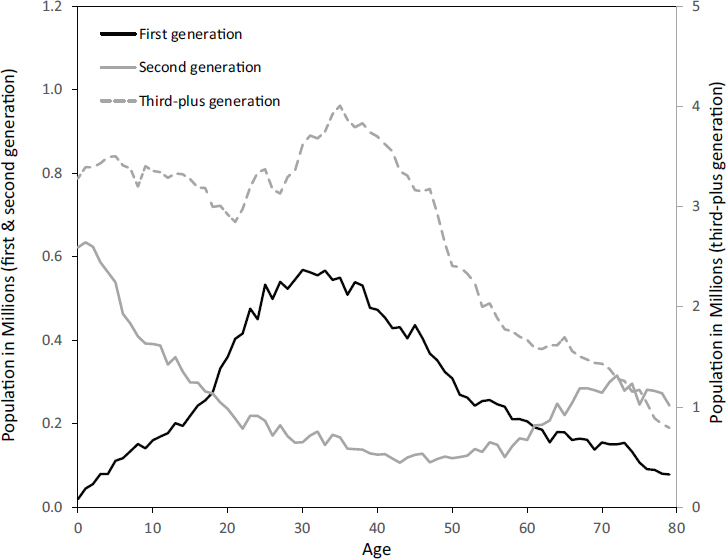

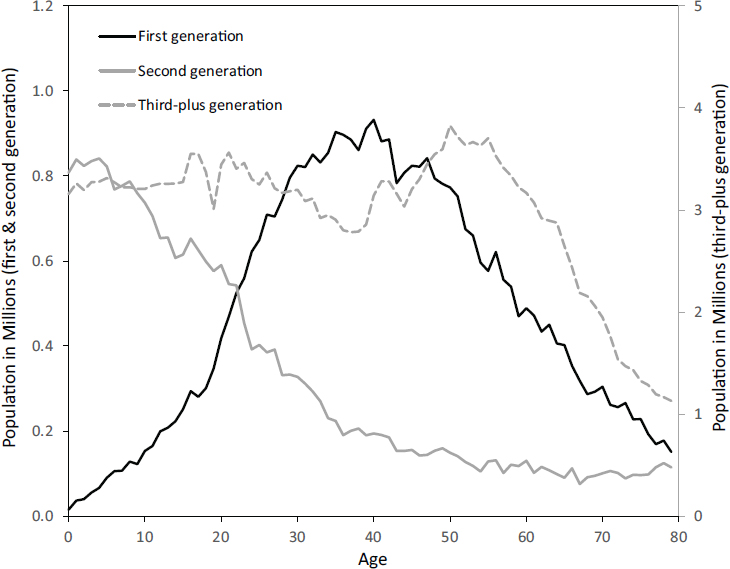

Immigrants and their children differ from natives in a variety of ways, but perhaps most notably in terms of age structure. Figure 8-1 shows the age structure in 1995 of first generation immigrants (the foreign-born) and their native-born children (the second generation), both plotted against the left vertical axis, and the rest of the native-born population (referred to here as the third-plus generation) plotted against the right axis. Figure 8-2 shows the age distributions of these three groups in 2012.

To repeat the definition of immigrant generations given in Chapter 1, “first generation” refers to foreign-born persons, excluding those born abroad and granted citizenship at birth because their parents are U.S. citizens. The second generation consists of U.S.-born persons who have one or more first generation parents. The third-plus generation includes U.S.-born persons of two U.S.-born parents and those born abroad but granted citizenship at birth because their parents are U.S. citizens. Note that persons born in U.S. outlying areas such as Puerto Rico are considered U.S. born

NOTE: “Third-plus generation” includes third and higher generations since ancestors arrived in the United States.

SOURCE: Data are from the 1994-1996 March Current Population Surveys.

NOTE: “Third-plus generation” includes third and higher generations since ancestors arrived in the United States.

SOURCE: Data are from the 2011-2013 March Current Population Surveys.

in this analysis because they are citizens at birth and thus, barring legal changes in citizenship, their movement to or from the 50 states would not be affected by immigration policy.

As both figures reveal, the first generation is heavily concentrated at working ages and does not contain many very young or very old people—the latter reflects the unusually small numbers of immigration arrivals during the mid-20th century. The second generation, which in 1995 still included children of early 20th century immigrants, is nearly the mirror image of the first generation, with comparatively few members of working age and higher shares of children and the elderly. By 2012, the second generation had become more concentrated at young ages, including younger adults, reflecting the substantial growth in their parents’ population—first generation immigrants of working ages—and the mortality of the second generation children of earlier immigrant waves. By contrast, the age structure of the third-plus generation has remained more stable. However, the aging of the Baby Boom generation has produced a more rectangu-

lar (rather than pyramidal) age distribution than was typical in the past, roughly equalizing the shares of young, working-age, and older third-plus generation Americans.

Age structure is crucially important for contextualizing fiscal impacts of a group with a particular nativity status at a point in time—or cross sectionally. While lifetime fiscal impacts may turn out to be more similar across groups, the short-term impact of a group that is concentrated at working ages when tax contributions are high will be more positive than that of a group that is, at that time, either relatively young or elderly or both, because the latter age ranges typically receive more transfers than they contribute in taxes. Given the patterns evident in Figures 8-1 and 8-2, if tax payments are attributed to the first generation, many of whom are of working age, and the use of public expenditures on education are attributed to their second-generation children, one would expect the current net fiscal impact of the first generation to be positive and the impact of the second generation to be negative. The net fiscal impact of the third-plus generation could be positive or negative, but is likely to have become less positive with the aging of the Baby Boom cohorts. After 20 more years, the age distribution of those currently in the first generation will look a lot more like the current third-plus generation.

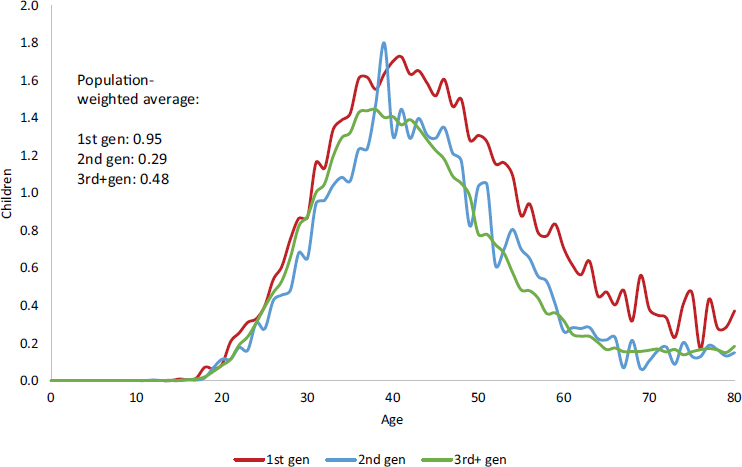

However, when the costs of dependent children are attributed to their parents—which, for many questions, will be the most relevant allocation—estimates of the current-year fiscal impact generated by first generation immigrants change dramatically. There are large counterbalancing fiscal impacts in an “immigrant household” grouping scheme. When a population is disproportionately of working ages, and therefore paying taxes and creating a positive fiscal impact, they are also likely to be disproportionately parents of children creating a fiscal negative, primarily in the form of public education costs. As shown below, this demographic characterization accurately describes first generation immigrants for the 1994-2013 period. In 2013, first generation immigrant households had a weighted average of 0.95 children in their households (see Figure 8-3)—much higher than the weighted averages of 0.29 and 0.48 for second generation and third-generation households. As indicated in Figure 8-3, some of this difference is accounted for by the fact that immigrants have had higher fertility over the past 17 or so years (suggested by the higher position at early parenting ages of the red line representing the first generation) and are also more likely to live in multigenerational households as elders.5 But these children-in-households profiles do not account for the full difference in the weighted averages across the

___________________

5 This is mostly “explained” by Hispanic ethnicity and family reunification policies that brought many older first generation immigrants to join their first generation children. Second generation persons have the lowest fertility, and in Figure 8-3 the whole curve for that generation is shifted a few years to the right compared with either the first or third-plus generation.

NOTE: Figures based on the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS)imputed child variable, which includes biological and adopted children and stepchildren of any age or marital status. Second generation includes persons with one or two foreign-born parents. “Third-plus generation” includes children with parents who are second or higher generation since ancestors arrived in the United States.

SOURCE: Data are from the March 2013 Current Population Survey.

three generational categories; in fact most of the difference can be attributed to the much higher percentage of immigrants in the parenting age range relative to other populations. The average number of children for the first generation is expected to decrease as the group grows older due to slower replacement (with new immigrants arriving) than in the past.

Trends in Education, Employment, and Earnings by Immigrant Status

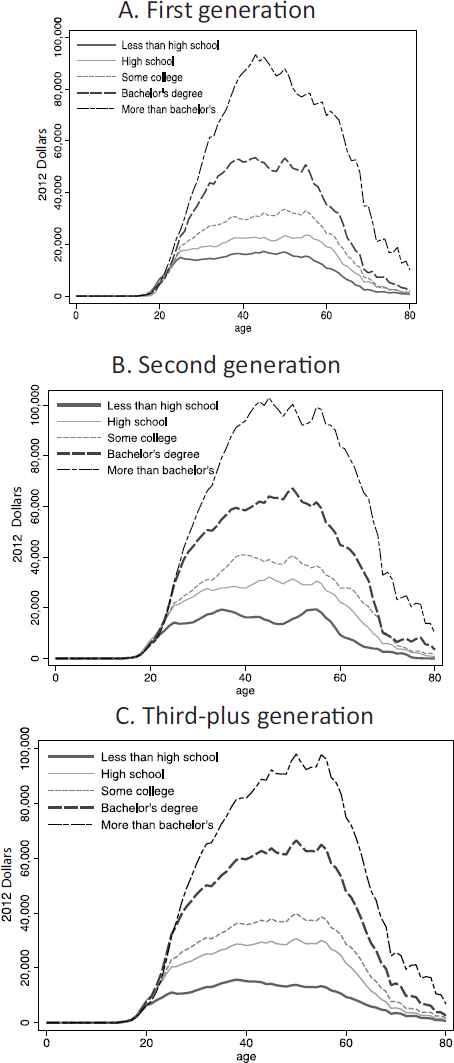

In addition to age and number of dependents, an individual’s education level and employment status are also important determinants of fiscal impact. Earnings and thus tax contributions tend to rise strongly with age and experience. They also rise with the level of education, and they track employment patterns in a predictable fashion. Benefits may vary inversely with education and employment to the extent that the safety net compensates need, but old-age entitlements also tend to rise with lifetime earnings and longevity, which are correlated positively with education.

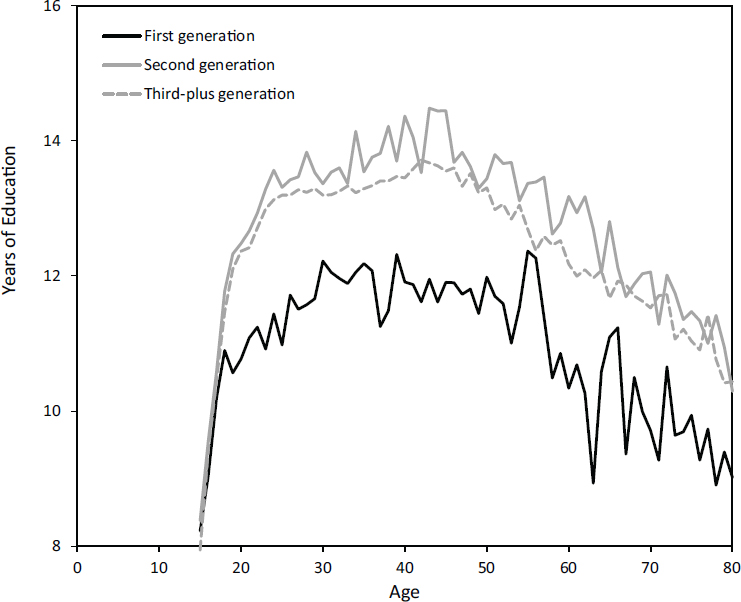

SOURCE: Data are from the March 1994 Current Population Survey.

Figure 8-4 shows average education levels across age by immigrant generation in 1994 as measured in the CPS.6 Average education declines for all groups beyond age 40 because earlier birth cohorts were less well educated. On average, first generation immigrants in 1994 had 1.5 fewer years of education than either the second or third-plus generations. Second generation education in 1994 was similar to but higher than that of the third-plus generation by 0.35 years; the children of immigrants tended to have higher education levels than other natives at every age.

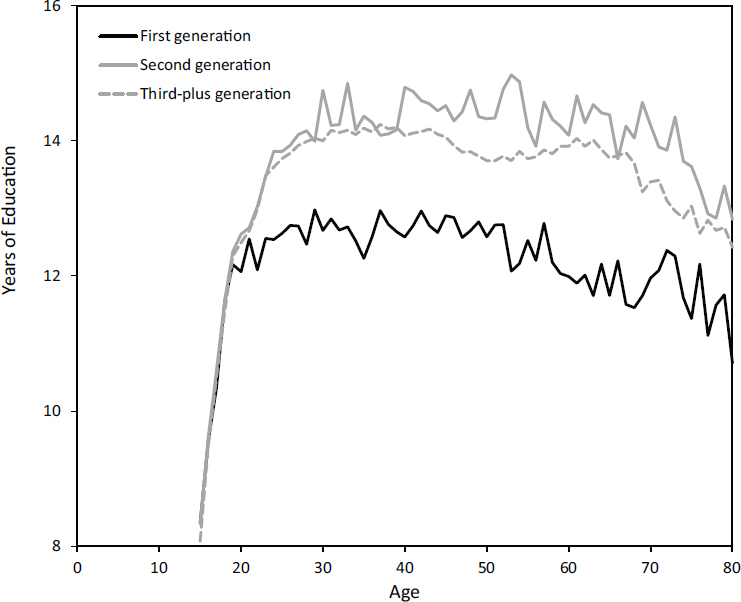

Age-specific education levels have been changing over time for all U.S. residents as younger cohorts with more education have replaced older cohorts with less. Figure 8-5 depicts the same age patterns of educational attainment as Figure 8-4 but for immigrant generations in 2013. Each line is higher than it was in 1994 by roughly 1 year. The gap between the first

___________________

6 We transformed educational attainment categories in the CPS into years of attainment using the crosswalk method suggested by Jaeger (1997).

SOURCE: Data are from the March 2013 Current Population Survey.

and third-plus generations has narrowed slightly during this interval from 1.5 to 1.25 years, while the second generation maintained the same 0.35 year advantage over the third-plus generation.

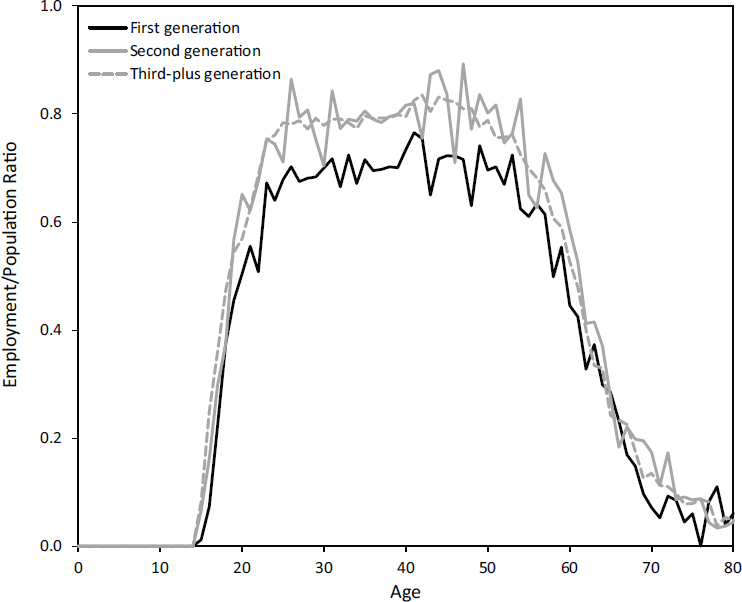

Patterns in employment across age also vary by immigrant status and have shifted somewhat over time. Figure 8-6 shows that in 1994, employment for all groups followed the expected inverted-U shape with increasing age and that immigrants worked less, at a given age, than natives (i.e., the first generation worked less than the second and third) except at some typical retirement ages.7 On average, immigrants ages 20 and older were about 5 percentage points less likely to be employed than the second or third-plus generations. But by 2013, as depicted in Figure 8-7, that gap had

___________________

7 As detailed in Chapter 3, the lower employment ratio of immigrants has historically been driven by lower participation of foreign-born women in the labor market. After an adjustment period, immigrant men often have employment ratios equivalent to natives and for some groups (e.g., low-skilled categories) they are considerably higher.

SOURCE: Data are from the March 1994 Current Population Survey.

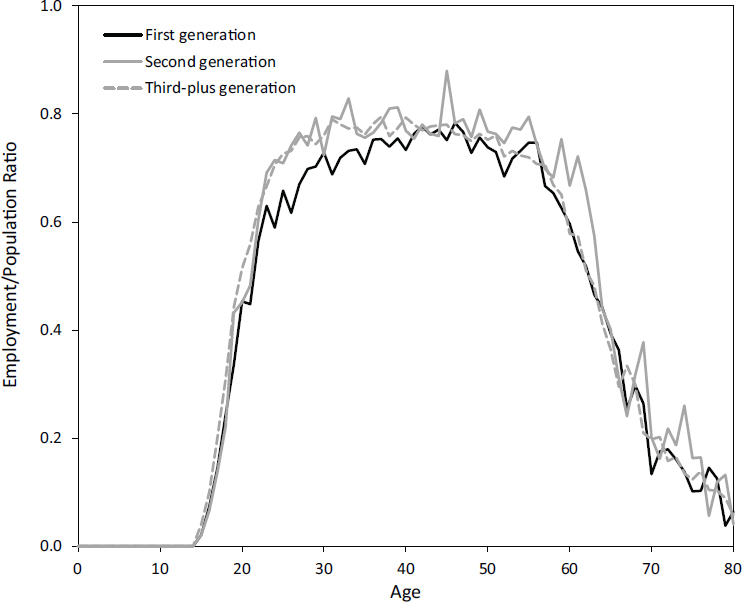

narrowed to 2 percentage points—mostly as a result of increasing employment of immigrant women (see Chapter 3), with lingering differences by immigrant status only under age 40. Employment rates by age among the second generation have remained broadly similar to those of the rest of the native-born population.

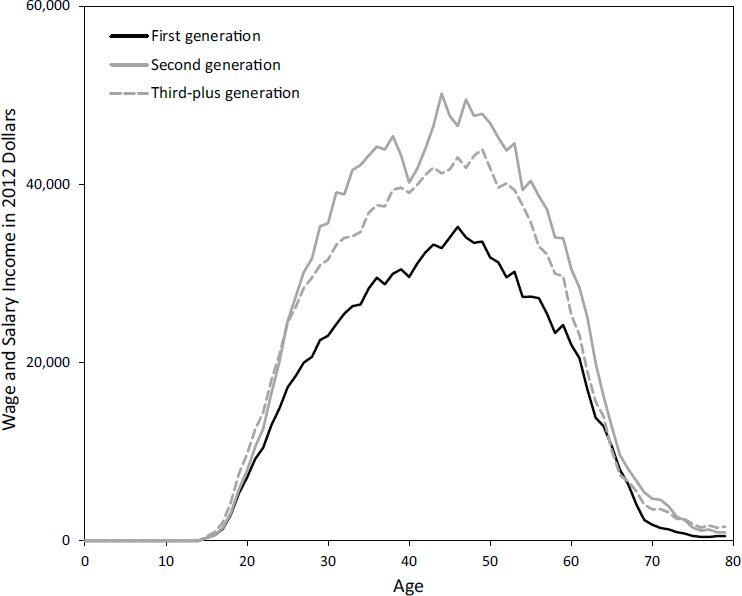

Although employment patterns of immigrants and natives have converged somewhat over time, if one adds the impact of wages the trends in relative earnings are more similar to trends in relative education, which display less convergence. Figure 8-8 shows large differences by immigrant generation in wage and salary income in 1995, measured in 2012 dollars and including those with zero earnings. On average, immigrants ages 20 and older in 1995 earned about $5,500, or 23 percent, less than natives of comparable age. In contrast, the second generation earned roughly $3,000, or 12 percent, more than the third-plus generation. Estimates vary, but an additional year of schooling may raise earnings by 10 percent (Card, 2001). Relative to that baseline, the immigrant earnings penalty is larger than

SOURCE: Data are from the March 2013 Current Population Survey.

might be expected, given their education disparities, but the remaining difference could be explained by reduced employment rates or hours worked. The earnings advantage of the second generation relative to the third-plus generation appears larger than would be explained by educational differences alone.

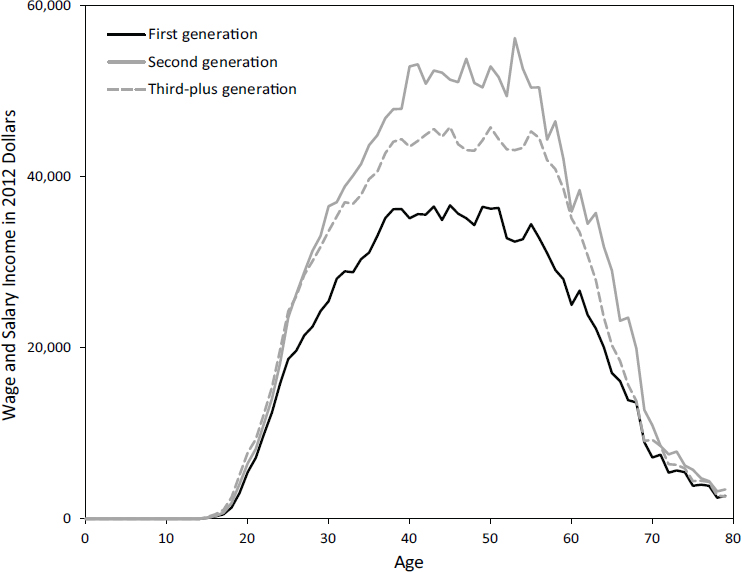

Figure 8-9, which shows earnings by age and immigrant status in 2012, visually suggests the second generation had pulled further away from the third, which is true. Note that these estimates are the average wage and salary income over people who are working and who are not. If one takes the average wage and salary income for the peak earning ages of 35-55 years old, earnings grew by about 12-13 percent for first and second generation persons but only by 9 percent for third-plus generation persons. So compared to third-plus generation wage and salary earnings, the second generation is pulling ahead and the first generation is catching up.

SOURCE: Data are from the March 1994-1996 Current Population Surveys.

Trends in Fiscal Flows by Age and Immigrant Generation

Now that we have considered many of the relevant characteristics of each generational group, we put this all together to examine fiscal flows. In this section we continue to take the individual as the unit of analysis, attributing tax receipts and benefit cost flows—which, when combined, yield net fiscal impacts—to each individual across the full age spectrum. This approach is useful for showing how fiscal flows vary by age and, controlling for age, across generational groups. However, such an approach disregards that children and other dependents are linked to independent adults, often from a different generational group. For this reason, in the section after this one, our analysis shifts focus by redefining generational groups to include dependents; so, for example, the first generation immigrant (the foreign-born) group includes foreign-born individuals ages 18 and older, plus their dependent first and second generation children (see Box 8-2). For now, in

SOURCE: Data are from the March 2011-2013 Current Population Surveys.

this section, we continue to look at the fiscal flows associated with individuals without taking their dependents into account.

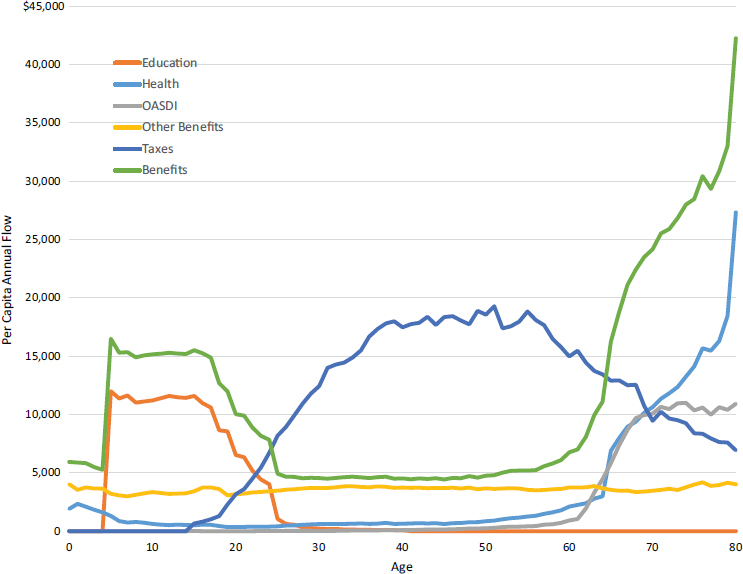

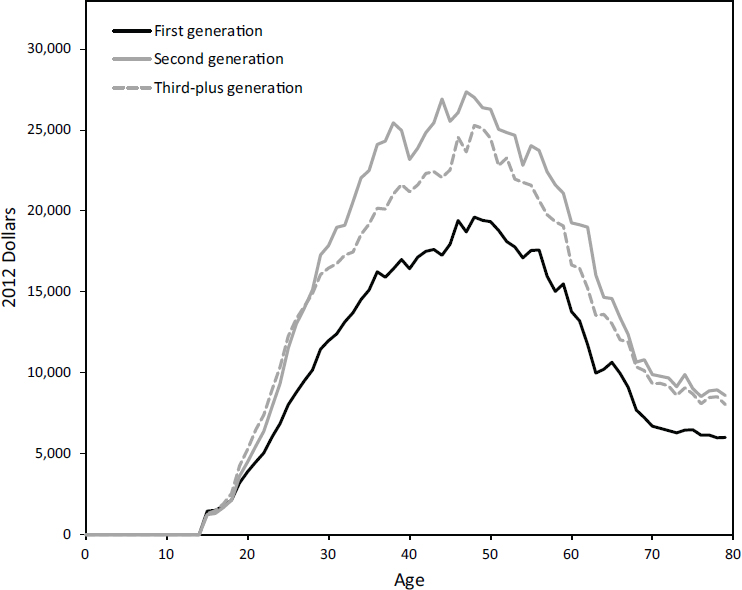

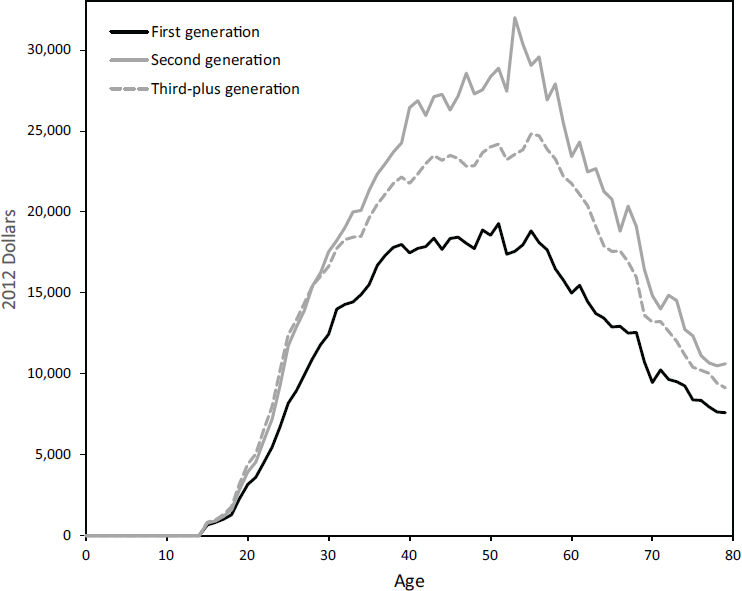

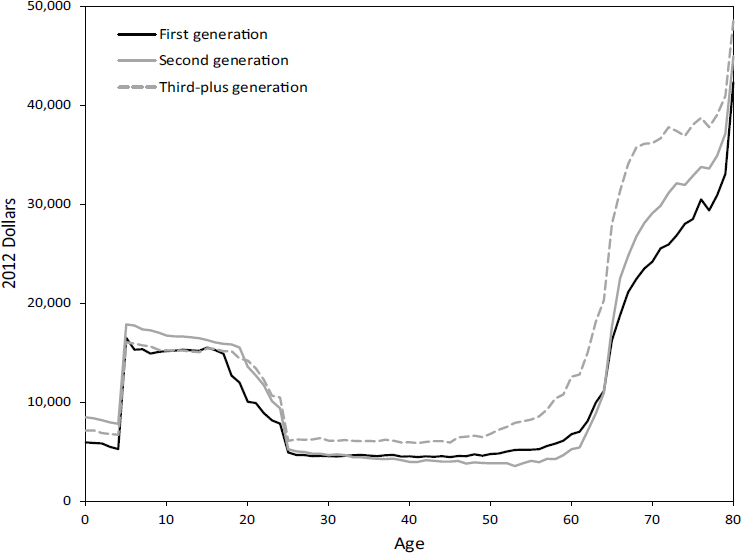

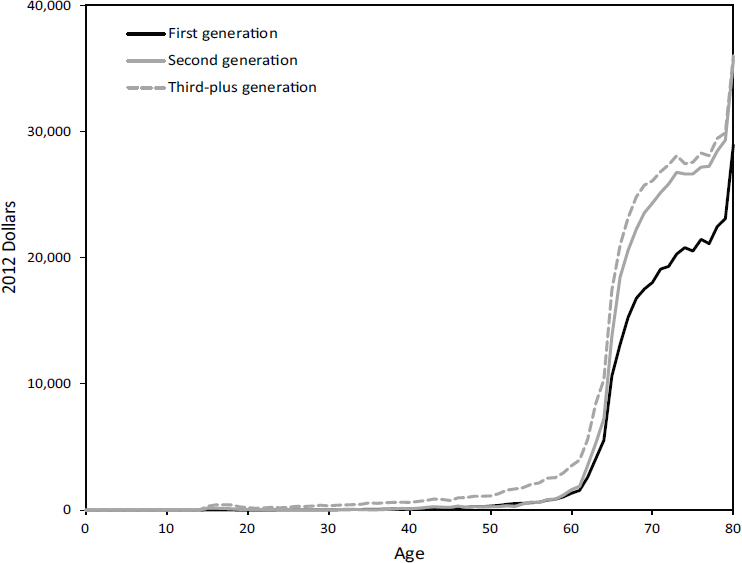

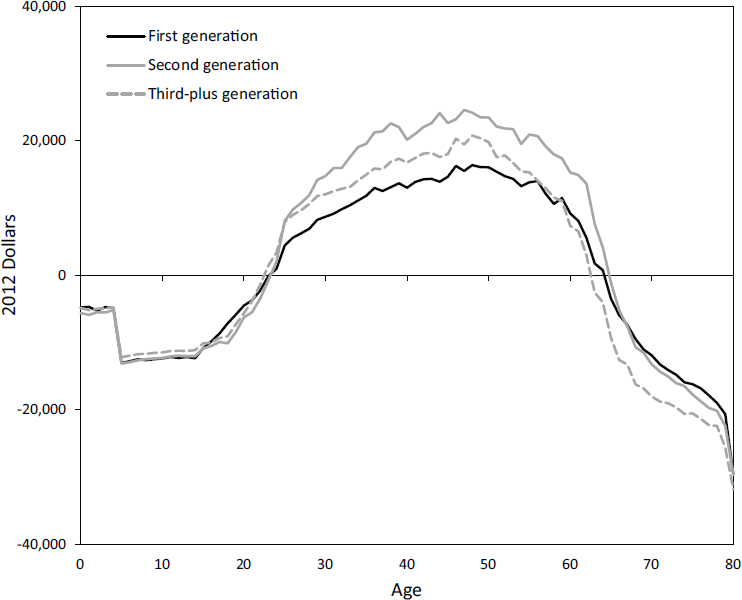

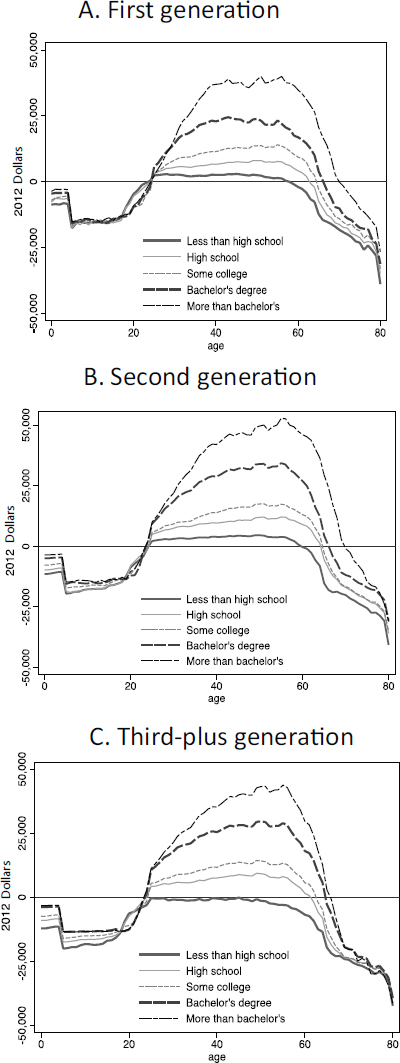

The cost of educating the young dominates fiscal flows early in the life cycle; contributions in the form of taxes paid dominate the middle years, and the cost of health care dominates the later years. This pattern is illustrated for first generation immigrants in Figure 8-10. Given that taxes and fiscal transfers in the United States are largely based on earnings, one would expect the persistent earnings disadvantage of immigrants and the persistent advantage of the second generation to be mirrored in patterns of tax payments and program utilization. This is certainly true in the case of taxes paid to all levels of government, which is shown in Figure 8-11 for the year 1995 and in Figure 8-12 for the year 2012. In both years, tax contributions strongly track the age profiles of wage and salary income shown in Figures 8-8 and 8-9 up to retirement ages. Because retirees continue to pay taxes on wealth and on some forms of income, their tax contributions remain positive even after their earnings cease. Immigrants ages 20 and

older contributed about 23 percent less than the third-plus generation8 in both years, while the second generation contributed 12 percent more than the third-plus in 2012 versus 10 percent in 1995.

Comparison of the data shown in Figures 8-8, 8-9, 8-11, and 8-12 also reveals relatively moderate increases over time in tax contributions relative to the growth in earnings. Between 1995 and 2012, per capita taxes paid rose 10 percent for immigrants, 13 percent for the second generation, and 11 percent for the third-plus generation. This is about half as fast as the growth in earnings during this period; if all taxes were levied on earnings, it would imply reductions in average tax rates of about 10 percent as well. One can see by comparing the graphs in Figures 8-11 and 8-12 that all of

___________________

8 Again, throughout this report, “third-plus generation” refers to all persons in the third and higher generations after immigration. In short, anyone resident in the United States who is not first or second generation is in the “third-plus generation” as defined for this chapter.

NOTE: All public spending is included, except pure public goods (defense, interest on the debt, subsidies). The “Health” category includes Medicaid and Children’s Health (CHIP) programs. Data are Current Population Survey (CPS)-based per-capita age schedules, smoothed and adjusted to National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) annual totals.

SOURCE: Data are from the March 2011-2013 Current Population Surveys.

the increase in inflation-adjusted tax contributions came from increases at older ages.

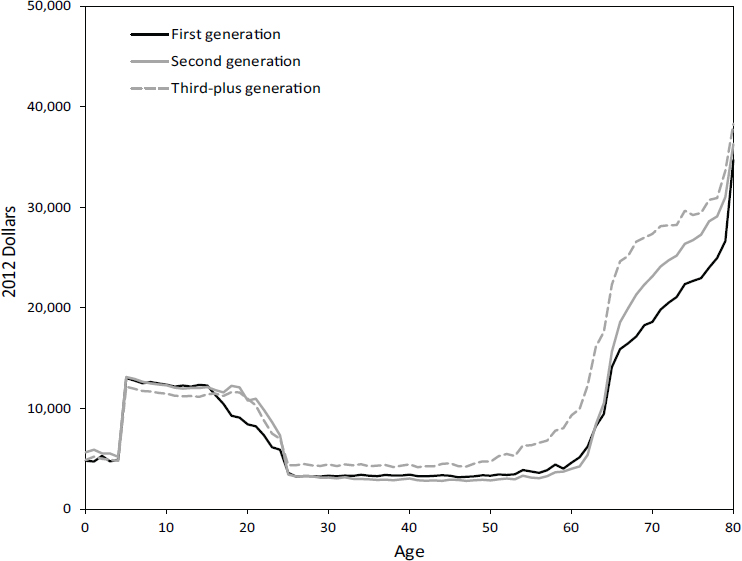

In contrast to the tax picture, per capita government benefits have risen in real terms across all age and nativity groups at an average rate that was slightly faster than the growth in earnings. This is largely attributable to the influence of current economic conditions compared to those in the 1990s: employment and wages have grown slowly in the wake of the Great Recession, while federal spending was increased to respond to the crisis. While the levels may have changed, Figures 8-13 and 8-14 (which attribute program costs of education at the age points of the children being edu-

SOURCE: Data are from the 1994-1996 March Current Population Surveys, normalized to program totals.

cated9) show that little change has occurred in the shape of the age profiles of benefits over time, nor has there been much change in the distribution of benefits across groups defined by immigrant status. But each age profile has risen, with growth most apparent (by comparing the lines in Figures 8-13 and 8-14) at the youngest and oldest ages.

Growth in per capita benefits from 1995 to 2012 was most rapid for those under age 20, where outlays increased 31 percent for immigrants, 38 percent for the second generation, and 33 percent for the third. But the second-most rapid rate of growth in benefits was actually among individuals of working ages, 20 to 64, which is not easy to see in the figures.

___________________

9 For other programs where the benefit depends on household size or that require the presence of children to qualify, the benefit is allocated equally to all members of the family unit receiving the benefit. These programs include AFDC, other welfare programs, and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).

SOURCE: Data are from the 2011-2013 March Current Population Surveys, normalized to program totals.

Benefits absorbed in the working-age range rose 33 percent for immigrants, 34 percent among the second generation, and 32 percent for the third-plus generation. Increases in benefit amounts at these ages were considerably less than the increases in benefit amounts for other age groups because benefits started from a smaller base. Benefit levels in retirement were already the highest of any age group, and they increased the most in dollar terms during this period. But the percentage growth in benefits for the retirement age group was only 16 percent for immigrants, 12 percent for the second generation, and 18 percent for the third-plus generation.

Another noteworthy aspect of these trends is that per capita benefits absorbed by the third-plus generation exceed those for the first and second

SOURCE: Data are from the 1994-1996 March Current Population Surveys, normalized to program totals.

generations at all ages past the typical years of college attendance.10 To the extent that receipt of some government benefits is contingent on years spent in the country, some of this is to be expected. But it is striking that the U.S.-born second generation absorbs fewer benefits than other natives at all such ages in both 1994 and 2012. The underlying patterns of program use contributing to differential benefit receipt by native-born children of immigrants and other natives at adult ages are primarily twofold. Up until about age 50, the third-plus generation uses means-tested programs such as Medicaid, unemployment benefits, food stamps, and the Earned Income

___________________

10 This finding is consistent with those in the peer-reviewed research literature. Sevak and Schmidt (2014), for example, link Health and Retirement Study survey data to restricted Social Security administrative data to show that immigrants have lower levels of benefits than do natives. The amount included here as state and local retirement benefits includes defined benefit plans but not defined contribution plans. The latter are typically not categorized as a public benefit and should be distinguished from payments out of tax revenues.

SOURCE: Data are from the 2011-2013 March Current Population Surveys, normalized to program totals.

Tax Credit (EITC) more intensively than does the second generation. After age 50, the third-plus generation absorbs more old-age benefits, such as Social Security pensions and disability payments, federal retirement payments, and state and local retirement benefits.

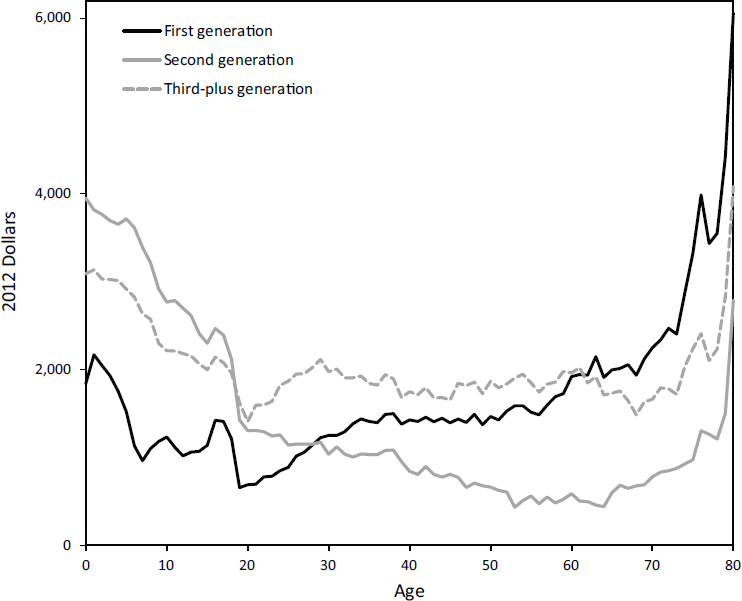

These patterns of program use are also revealed in Figure 8-15, which shows receipt of benefits associated with federal old-age support programs (Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid payments to nursing homes, federal worker retirement, and other programs), and in Figure 8-16, which shows federal means-tested programs for the poor (the rest of Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, unemployment insurance, food stamps, the EITC, and other support); data are shown for 2012 in both figures. Old-age benefits are nonzero prior to retirement because of the inclusion of disability insurance, but they rise rapidly for all groups after age 62. Immigrants receive less Social Security than natives because they have typically paid less into the system or have immigrated after working ages. Prior to age 62, the excess spending generated by the third-plus generation relative to the second generation is

SOURCE: Data are from the 2011-2013 March Current Population Surveys, normalized to program totals.

due to federal disability insurance, whereas after age 62 it is attributable to federal retirement benefits (i.e., Social Security), which rise steeply with age.

For working-age individuals, the means-tested federal antipoverty benefits tracked in Figure 8-16 show the third-plus generation as receiving the highest per capita benefits. At young ages, per capita benefit receipt is highest for the second generation (the children of immigrants). A similar conclusion can be drawn from the data on program participation rates. As detailed in Chapter 3, U.S.-born children with two immigrant parents have higher program participation rates than those with one or two native-born parents because they are likely to live in households with lower than average incomes and, since they are U.S. born, they are eligible for various safety net programs. At the oldest ages, the first generation absorbs the most means-tested antipoverty benefits on a per capita basis.11

___________________

11 Of course, the aggregate expenditure amounts are greatest for natives because they are by far the largest group.

SOURCE: Data are from the 2011-2013 March Current Population Surveys, normalized to program totals.

Medicaid and Supplemental Security Income, which are included here and are typically characterized as means-tested, effectively serve as substitutes for Medicare and Social Security for older immigrants, many of whom do not qualify for those old-age entitlements because of abbreviated domestic work histories. Differences by nativity in usage of means-tested programs at working ages are partially mechanical in nature; recent arrivals do not qualify for many of these programs initially. But program eligibility cannot explain the differences between the second and third-plus generations during working ages, so these differences are likely instead driven primarily by more favorable socioeconomic status among the second generation.

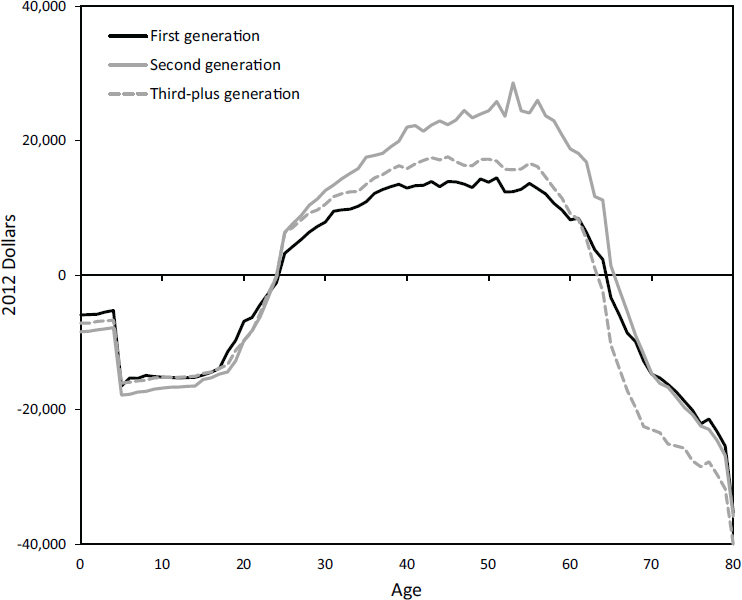

Net fiscal impacts by age and immigrant status are depicted for 1995 and 2012 in Figures 8-17 and 8-18, respectively. These graphs reveal that the second generation has had a more positive net fiscal impact at almost every age than either the first or third-plus generation. Individuals of the

SOURCE: Data are from the 1994-1996 March Current Population Surveys, normalized to program totals.

second generation contribute considerably more in taxes during working ages than either of the other generational groups, although they also absorb slightly more benefits at younger ages. By contrast, at least prior to around age 60, the net fiscal impact of the first generation has been consistently less positive than the other two generational groups.

Although the third-plus generation contributes more in taxes during working ages than does the first generation, and thus its net fiscal impact during working ages is more positive than immigrants, this pattern switches in retirement. In old age, the third-plus generation has consistently been more expensive to government on a per capita basis than either the first or second generation, despite the higher per capita utilization of means-tested benefits in old age by the first generation.

Net fiscal impacts at the state and local level by age and immigrant status (not shown, but based on the data sources cited for the figures)

SOURCE: Data are from the 2011-2013 March Current Population Surveys, normalized to program totals.

broadly conform to these patterns, with larger deficits at younger ages for the first and second generations, followed by larger surpluses at working and older ages. Federal net fiscal impacts (not shown in the figures) are also similar in pattern to those illustrated but, because transfers to the young are primarily channeled through states and localities, the negative net impacts for individuals positioned in the pre-working ages of the life cycle are smaller (in absolute terms).

Annual Fiscal Impacts by Immigrant Status

In this section, the panel considers the fiscal impact of different population subgroups defined by immigrant status. The total net fiscal impact of a subpopulation depends on its age structure, depicted earlier in this chapter, and on the age profile of net fiscal impacts, as presented in the preceding

discussion. Because U.S. subpopulations identified by nativity are so different in size, their aggregate fiscal impacts also vary widely in magnitude, which complicates comparisons. Thus, it is useful to recast the net fiscal impacts of immigrant groups either on an average (per capita) basis, as was done above, or as the ratio of government receipts contributed (taxes paid) to expenditures on benefits received, as was done by Dustmann and Frattini (2014). When this “fiscal ratio” is greater than unity, the group pays more in taxes than it receives in benefits, whereas a fiscal ratio less than unity indicates that the group pays less in taxes than it receives in benefits. However, this approach does not control for a group’s age structure, which we have seen is quite important—this is a topic to which we return later in the chapter when we examine the fiscal impact of the foreign born and native born controlling for their characteristics.

We begin by examining the annual fiscal impacts of all age cohorts of three broadly defined generational groups as identifiable in our pooled March CPS data samples for the 1994-2013 analysis period. Our definitions of first, second, and third-plus generation are unchanged from earlier in the chapter. However, for the analysis here—and in contrast to the analyses up to this point in the chapter—we have created groupings that are partially mixed. The first group consists of first generation immigrants (the foreign-born) ages 18 and older, plus their dependent first and second generation children (see Box 8-2). The second group consists of independent individuals (those ages 18 and older) in the second generation plus their dependents (who typically are third generation by nativity status). The third group consists of independent individuals in the third and higher generations, plus their dependents.12 The rationale, in this exercise, of grouping dependents with their parents is so that the full fiscal impact created by an immigrant or a native born person (which includes their family members, or other dependents) can be estimated for a given year; without the presence of the independent persons to which they are linked, dependents could not factor into the fiscal picture. Later in this chapter, we analyze the impact of these same three generational groups on fiscal impact, adjusting for age, education, and other characteristics; this analytical framework allows for assessment of the net fiscal impacts, at the federal and state levels of government, of these first and second-generation groups separately, in comparison to the third-plus generation group, specified as the reference group.

Associating dependent children with an independent individual responsible for them entails assigning the children to the generational group

___________________

12 For all three groups, dependent children—identified at the individual level in the CPS data—are included in their parents’ generational group. Therefore, some second generation individuals (i.e., dependent children) appear in the first generation group; the same logic applies to the membership of the groups labeled “second generation” and “third-plus generation.”

defined by the nativity status of that individual (typically their parent(s)); this is done for the dependent children of independent individuals in each of the generational groups. Dependent children are assigned to the parental generation if one or more independent parents are present in the household.13 If there are no parents in the household, then the generational group of the oldest co-resident independent relative is assigned. Defining generational groups in this way attributes the costs to governments associated with dependent children—most notably, in terms of magnitude, public expenditures on education—to the generation of a parent or relative responsible for raising the child.14 Of course, dependent children of any population subgroup, foreign-born or native-born, generate a net fiscal cost (they are not yet working and they need to be educated). As expected, and as shown quantitatively below, the fiscal costs associated with dependent children to some extent counterbalance the positive fiscal impact for the first generation (see Figures 8-17 and 8-18) created by the fact that, during the analysis period at hand, this generation was disproportionately of working age and hence paying taxes (refer to Figures 8-1, 8-2, 8-11, and 8-12).

Table 8-1 reports subpopulation size, per capita fiscal impacts, and fiscal ratios for these groups of independent-persons-plus-dependents at different levels of government in 1994 and 2013. The cost of public goods is assigned on an average cost basis as specified in scenario 1 (defined in Box 8-1, above); results for the alternative scenarios are discussed later in the chapter. Recall, that these may be considered relatively conservative estimates because the addition to government costs associated with public goods (like national defense) created by one addition (or a small number of additions) to the population may be close to zero. The calculations reveal that the population group consisting of immigrants (first generation) and their dependent children has a lower fiscal ratio than either of the groups composed of native-born independent individuals and their dependent children. The overall fiscal ratio of the second generation (independents plus their dependents) is more similar to that of the first generation group in 1994 but more similar to that of the third-plus generation group in 2013; we provide an explanation of this observation below. A major source of the overall differential between the first generation group and the two native-born groups originates from the considerably lower fiscal ratio at the state

___________________

13 It is possible for a dependent to be associated with independent persons in different generational groups (e.g., a child of a first generation mother and third-plus generation father). In order to sort the group of children with this ambiguous generational identification, a randomly selected half are assigned to the mother’s generation and the other half to the father’s. This is done instead of splitting the flows of each child to avoid ending up with a group-weighted per capita flow that does not match the total population per capita flow.

14 In those few cases where there was no independent co-resident parent, the associated independent person was usually a grandparent.

| 1st Generation and Their Dependents (population: 29.9 million) | 2nd Generation and Their Dependents (population: 20.8 million) | 3rd Generation and Their Dependents (population: 212.2 million) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Outlays | Receipts | Receipts/Outlays | Outlays | Receipts | Receipts/Outlays | Outlays | Receipts | Receipts/Outlays |

| Federal | 8,408 | 5,769 | 0.686 | 13,853 | 8,022 | 0.579 | 8,996 | 7,734 | 0.860 |

| State and Local | 5,104 | 3,215 | 0.630 | 4,601 | 4,659 | 1.013 | 4,621 | 3,901 | 0.844 |

| Total | 13,511 | 8,985 | 0.665 | 18,454 | 12,681 | 0.687 | 13,617 | 11,635 | 0.854 |

| 1st Generation and Their Dependents (population: 55.5 million) | 2nd Generation and Their Dependents (population: 23.3 million) | 3rd Generation and Their Dependents (population: 237.3 million) | |||||||

| 2013 | Outlays | Receipts | Receipts/Outlays | Outlays | Receipts | Receipts/Outlays | Outlays | Receipts | Receipts/Outlays |

| Federal | 9,767 | 7,117 | 0.729 | 13,093 | 9,495 | 0.725 | 12,050 | 9,473 | 0.786 |

| State and Local | 6,141 | 3,769 | 0.614 | 6,101 | 5,039 | 0.826 | 5,844 | 4,813 | 0.823 |

| Total | 15,908 | 10,887 | 0.684 | 19,194 | 14,534 | 0.757 | 17,894 | 14,286 | 0.798 |

NOTE: “Dependent” and “independent” are defined as in Box 8-2. Outlays include all government spending, including interest payments and public goods, which are allocated equally to all groups on a per capita basis. Population counts are the sum of independents and dependents in each group. Data are from March Current Population Surveys. Estimates are for scenario 1 (see Box 8-1) which assigns the average costs of public goods to new immigrants, as opposed to the marginal cost, and includes interest payments.

and local level of government for the former group whose adult members, during the analysis period, were more likely to be of parenting age and who also experienced higher fertility rates.15 These differentials in state- and local-level fiscal impacts largely reflect differences in the groups’ total cost of educating dependents.16 In the longer term, these dependent children will grow up to be contributing adults and thus these educational expenditures may reasonably be considered an investment in their future productivity.

The first generation group displays a lower fiscal ratio than does the third-plus generation group at the federal level. This fiscal effect, and a portion of the fiscal difference at the state and local level as well, reflects the lower average education levels—and, related to these, the lower wages and employment—of the first generation independent persons compared to the second and third-plus generation independents in the other two groups (see the cross-sectional results presented in the previous section). Interestingly, the fiscal ratios in Table 8-1 at the federal level actually rose for the first and second generation groups between 1994 and 2013, whereas they fell for the third-plus generation group. To some extent, this may reflect new programs and expansion of others (such as EITC) that some native-born individuals are eligible for and some immigrants are not, as well as declining fertility rates among immigrants. But the trend is mainly driven by the aging of the native-born population. In 2013, the third-plus generation (as defined by nativity status) population included a higher proportion of elderly persons than it did in 1994. The second generation population, in contrast, had a relatively much higher concentration of individuals in the fiscally expensive retirement age groups in 1994 than in 2013 (refer back to Figures 8-1 and 8-2). As described in Chapter 2, at the beginning of the 1994-2013 analysis period, a large portion of the second generation consisted of the children of earlier heavy waves of immigrants who arrived around the beginning of the 20th century and were thus an older group. The elderly are, of course, associated with increased federal outlays. By 2013, more of the children of newer waves had reached adulthood and were thus more heavily represented among second-generation independent persons, reducing the average age of this group.

Readers will note that the figures in Table 8-1 translate into quite large fiscal shortfalls overall—the fiscal ratio (Receipts/Outlays columns) falls well below 1.0 for all three groups. For 2013, the 55.5 million first generation independent persons and their dependents, 23.3 million second

___________________

15 We stress again that these are averages; the foreign-born are an extremely heterogeneous group along many of the dimensions being considered here, and consequently they are also heterogeneous in their per capita fiscal ratios.

16 The per-child cost of education in our estimates is the same for all groups. The differences referenced here are due to differences in the average number of dependent children per independent individual in the three groups.

generation independent persons and their dependents, and 237.3 million third-plus generation independent persons and their dependents yield a total fiscal shortfall of $1,243 billion. The total fiscal burden is $279 billion for the first generation group (average outlays of $15,908 minus average receipts of $10,887, multiplied by 55.5 million individuals), $109 billion for the second generation group (average outlays of $19,194 minus average receipts of $14,534, multiplied by 23.3 million individuals), and $856 billion for the third-plus generation group (average outlays of $17,894 minus average receipts of $14,286, multiplied by 237.3 million individuals). Under this scenario, the first generation group accounts for 17.6 percent of the population but 22.4 percent of the total deficit. In contrast, the second generation group accounts for just a slightly higher share of the total deficit (8.7%) than its share in the population (7.4%). The third-plus generation group, with 75 percent of the population, accounts for just 68.9 percent of the deficit. Note that, while the fiscal shortfall for the average person in the first-generation group (i.e., the per capita shortfall) was larger than was the per capita shortfall in either native-born group, the shortfall for the latter two groups would have been larger without the presence of the first generation group. This is because federal expenditures on public goods such as national defense (assigned to immigrants on an average cost basis in scenario 1) would have to be divided among a smaller population of second and third-plus generation individuals.

Cross-checking against alternative sources indicates that, although the overall deficit numbers in Table 8-1 are large, the totals (for all three groups) are consistent with actual deficit figures in the National Income and Product Accounts for the federal and state-and-local level budgets combined: The difference in 2013 between total taxes and contributions for government social programs ($4,332 billion) and total expenditures including all public goods ($5,584 billion) was $1,252 billion. The consolidated deficit for that year was actually smaller by about $400 billion because, on the revenue side, government asset income (which immigrants are assumed to not pay) and current transfer receipts (mainly fines and fees) are not included in the panel’s estimates.

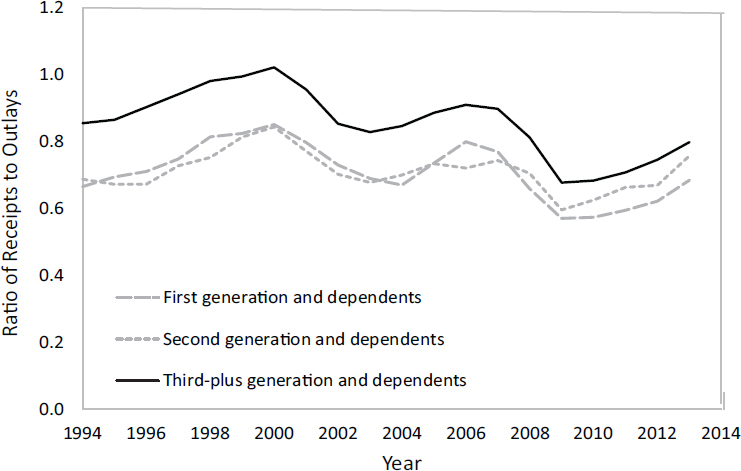

To elaborate on trends in net fiscal impacts since The New Americans (National Research Council, 1997), Figure 8-19 plots the total fiscal ratio of receipts to outlays for the three generation groups, as defined for Table 8-1, across all years since 1994. Crucially, there is no correction made here (or in Table 8-1) for different age distributions across groups and over time. The net impact of each group grows more positive during the boom of the late 1990s before falling and rising during and after the mild recession of 2001, then falling and rising again during and after the financial crisis of 2008

SOURCE: Data are from the 1994-2013 March Current Population Surveys normalized to program totals. Estimation is for scenario 1, which assigns the average costs of public goods including interest payments to both immigrants and the native-born.

which precipitated the Great Recession.17 In addition to this cyclical variation, a noteworthy pattern here is the reduction in the gap between the first and second generation groups, represented by the two dashed lines, and the third-plus generation group, shown by the solid line. As the Table 8-1 data show, the second generation group in particular becomes quite similar by 2014 to the third-plus generation group.

While all part of the same story, the data representations in Figure 8-19 and in Table 8-1 reveal determinants of the fiscal impact of generational groups that are quite distinct from those previously captured in Figures 8-5 through 8-12. The earlier figures show the second generation (including independents and dependents of that generation together) exceeding even the third-plus generation along a number of dimensions, including years of education, per capita wage and salary income, and per capita taxes paid.

___________________

17 The recession of the early 2000s began in March 2001 and ended in November 2001; the Great Recession began in December 2007 and ended in June 2009. These dates are determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research’s Business Cycle Dating Committee at http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html [November 2016].

However, the data in the earlier figures provide estimates of these variables for individuals in each generation group by age, regardless of calendar year. In contrast, Figure 8-19 and Table 8-1 present data in a way that prominently reflects group demographic composition and changes therein over the 1994-2013 analysis period. In Table 8-1 and Figure 8-19, the comparatively low fiscal ratios for the second generation group, relative to the third-plus generation group, in the beginning of the period reflect the former group’s comparatively high concentration in the (fiscally expensive) retirement ages of the distribution at that time. The closing gap in fiscal ratios between the generations shown in Figure 8-19 reflects the more recent profile, which is now younger for the second generation, as well as the relative aging of the third-plus generation into retirement. In other words, the second generation has been gaining something of a demographic advantage from a fiscal perspective as the composition of its adult population has become younger while the third-plus generation has been growing older. The aging of the third-plus generation has also reduced the gap in fiscal ratios between the first and third-plus generation groups. The elderly are associated with increased federal outlays regardless of nativity status. The higher number of dependent children among the first generation, and the associated fiscal costs particularly at the state and local levels, offset this reduction of the fiscal ratio gap between the first generation group and the native–born groups somewhat. This interpretation of the relative fiscal impacts of the first, second, and third-plus generation groups (as defined for Table 8-1) becomes clearer below, where fiscal impacts of these groups are compared while controlling for age and other characteristics. The more favorable fiscal situation of the second generation group compared to the first is germane to a consideration of the impact of immigration since many people think of this group as part of the immigrant stock.

We now turn to the set of alternative scenarios defined in Box 8-1 above (following the approach of Dustmann and Frattini, 2014). Table 8-2 repeats the estimates for 2013 under scenario 1 (from the lower panel of Table 8-1) and then presents the estimates for 2013 under the seven alternative scenarios. For each scenario, the changes from scenario 1 are applied to all members of a defined generational group. For example, in the subset of scenarios developed to assess changes in magnitude when assuming a marginal-cost allocation of public goods (scenarios 5 through 8), instead of the average cost allocation in scenarios 1 through 4, the marginal-cost allocation is applied to all members of the first generation group, including the second-generation dependent children of first generation independents. In these scenarios, the total net fiscal impact of the first generation group becomes much more favorable, as it must mathematically. In each of scenarios 5 through 8, the total fiscal ratio for the first generation group now exceeds that for the second and third-plus generation groups. The main

| 2013 | 1st Generation and Their Dependents (population: 55.5 million) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outlays | Receipts | Receipts/Outlays | |||

| Scenario 1 | Immigrants pay average cost of public goods | Federal | 9,767 | 7,117 | 0.729 |

| State and Local | 6,141 | 3,769 | 0.614 | ||

| Total | 15,908 | 10,887 | 0.684 | ||

| Scenario 2 | Scenario 1, but interest costs are excluded | Federal | 8,466 | 7,117 | 0.841 |

| State and Local | 5,517 | 3,769 | 0.683 | ||

| Total | 13,983 | 10,887 | 0.779 | ||

| Scenario 3 | Scenario 1 but immigrants’ sales taxes are 80% | Federal | 9,767 | 7,051 | 0.722 |

| State and Local | 6,141 | 3,475 | 0.566 | ||

| Total | 15,908 | 10,525 | 0.662 | ||

| Scenario 4 | Scenario 1, but new immigrants’ corporate taxes are zero | Federal | 9,767 | 6,937 | 0.710 |

| State and Local | 6,141 | 3,769 | 0.614 | ||

| Total | 15,908 | 10,706 | 0.673 | ||

| Scenario 5 | Immigrants pay marginal cost of public goods | Federal | 6,154 | 7,117 | 1.157 |

| State and Local | 5,515 | 3,769 | 0.683 | ||

| Total | 11,669 | 10,887 | 0.933 | ||

| Scenario 6 | Scenario 5, but interest costs are excluded | Federal | 6,154 | 7,117 | 1.157 |

| State and Local | 5,515 | 3,769 | 0.683 | ||

| Total | 11,669 | 10,887 | 0.933 | ||

| Scenario 7 | Scenario 5, but immigrants’ sales taxes are 80% | Federal | 6,154 | 7,051 | 1.146 |

| State and Local | 5,515 | 3,475 | 0.630 | ||

| Total | 11,669 | 10,525 | 0.902 | ||

| Scenario 8 | Scenario 5, but new immigrants’ corporate taxes are zero | Federal | 6,154 | 6,937 | 1.127 |

| State and Local | 5,515 | 3,769 | 0.683 | ||

| Total | 11,669 | 10,706 | 0.917 | ||

NOTE: See note to Table 8-1. The eight estimation scenarios are described in Box 8-1 and accompanying text.

| 2nd Generation and Their Dependents (population: 23.3 million) | 3rd-plus Generation and Their Dependents (population: 237.3 million) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outlays | Receipts | Receipts/Outlays | Outlays | Receipts | Receipts/Outlays |

| 13,093 | 9,495 | 0.725 | 12,050 | 9,473 | 0.786 |

| 6,101 | 5,039 | 0.826 | 5,844 | 4,813 | 0.823 |

| 19,194 | 14,534 | 0.757 | 17,894 | 14,286 | 0.798 |

| 11,792 | 9,495 | 0.805 | 10,749 | 9,473 | 0.881 |

| 5,477 | 5,039 | 0.920 | 5,220 | 4,813 | 0.922 |

| 17,269 | 14,534 | 0.842 | 15,970 | 14,286 | 0.895 |

| 13,093 | 9,507 | 0.726 | 12,050 | 9,486 | 0.787 |

| 6,101 | 5,092 | 0.835 | 5,844 | 4,868 | 0.833 |

| 19,194 | 14,600 | 0.761 | 17,894 | 14,353 | 0.802 |

| 13,093 | 9,536 | 0.728 | 12,050 | 9,513 | 0.790 |

| 6,101 | 5,039 | 0.826 | 5,844 | 4,813 | 0.823 |

| 19,194 | 14,576 | 0.759 | 17,894 | 14,326 | 0.801 |

| 13,734 | 9,495 | 0.691 | 12,691 | 9,473 | 0.746 |

| 6,216 | 5,039 | 0.811 | 5,959 | 4,813 | 0.808 |

| 19,949 | 14,534 | 0.729 | 18,650 | 14,286 | 0.766 |

| 12,208 | 9,495 | 0.778 | 11,165 | 9,473 | 0.848 |

| 5,478 | 5,039 | 0.920 | 5,221 | 4,813 | 0.922 |

| 17,686 | 14,534 | 0.822 | 16,386 | 14,286 | 0.872 |

| 13,734 | 9,507 | 0.692 | 12,691 | 9,486 | 0.747 |

| 6,216 | 5,092 | 0.819 | 5,959 | 4,868 | 0.817 |

| 19,949 | 14,600 | 0.732 | 18,650 | 14,353 | 0.770 |

| 13,734 | 9,536 | 0.694 | 12,691 | 9,513 | 0.750 |

| 6,216 | 5,039 | 0.811 | 5,959 | 4,813 | 0.808 |

| 19,949 | 14,576 | 0.731 | 18,650 | 14,326 | 0.768 |

source of the shift occurs at the federal level, where the cost of public goods such as national defense accrues. However, even the fiscal ratio for the state and local levels rises somewhat for the first generation group, since there are some public costs that accrue to governments at the subnational level.

Looking in greater detail at the results in Table 8-2, one can see that, as alluded to above, the biggest difference across the scenarios is in the way that government spending on public goods like national defense and interest payments is allocated. Government expenditures on public goods are large at the federal level in the United States, with defense outlays totaling $617.1 billion and federal interest payments adding $417.4 billion in 2013. Subsidies and grants accounted for another $125 billion. All together, these categories of federal spending accounted for almost one-third of total federal spending as reflected in the National Income and Product Accounts that year. Therefore, allocating none of the costs associated with these public goods to individuals in the first generation group, as is done under the marginal-cost scenarios, changes the fiscal ratio estimates significantly. Fiscal ratios for the first generation group rise and become considerably closer to one relative to scenarios 1 through 4, in which the average cost of public goods is allocated to the full population, including immigrants and their dependents. Most but not all of the increase in the fiscal ratio for the first generation group is linked to the change in the public goods assumption that results in vastly reduced federal spending on this group—from an estimate of $9,767 per individual in scenario 1 down to $6,154 in scenario 5—a reduction that raises the ratio of receipts to outlays from 0.729 to 1.157. State and local spending on the first generation group also falls modestly for the marginal-cost scenarios, due to a reduction in some interest payments and subsidies treated as public goods, but not by as much as the federal spending declines. In scenario 5, the total fiscal burden for the first generation group drops to $43.4 billion while it rises to $126.2 billion for the second generation group and to $1,035.6 billion for the third-plus generation group. In this scenario, the first generation group accounts for less than 4 percent of the total deficit (while still of course accounting for 17.6 percent of the sample population). As noted, government expenditures on public goods account for almost one-third of total federal spending. Therefore, the average-cost versus marginal-cost assumption—along with other assumptions having to do with how expenditures are allocated—are quantitatively extremely important in driving estimates of the fiscal impact different generational groups.

Thus, while for scenarios 1 through 4 the first generation group displays slightly lower but quite comparable fiscal ratios at the federal level, compared with the third-plus generation group,18 the ordering reverses

___________________

18 Here as elsewhere in the report, “third-plus generation” is a short-hand way of referring to everyone who is neither an immigrant nor a U.S-born child of at least one immigrant parent.

and a wide gulf between the first and third-plus generation groups appears for scenarios 5 through 8. If it is assumed that spending on defense and other pure public goods does not increase with a marginal immigrant and instead these costs are assigned to the native-born only (both second and third-plus generation groups), the first generation group appears in a much more favorable light relative to the scenarios in which its members share in the cost of pure public goods equally. Comparisons between scenarios 1-4 and 5-8 also reveal a small compounding effect associated with the native-born groups (the second and third-plus generation groups). A consequence of the zero marginal-cost allocation assumption is that these two groups appear more costly because they bear an increased burden in public goods costs—costs that in these scenarios are spread across a population that is decreased by the number of foreign-born and their dependent children.

Results also vary somewhat across the other scenarios in Table 8-2, but these differences pale in comparison with the choice between assuming marginal cost versus average cost for public goods. Excluding interest payments—that is, when only the fiscal flows generated by current, but not by past, program usage as reflected in deficits, debt, and interest payments are counted—as is done for scenarios 2 and 6, outlays for all generational groups are naturally reduced and the ratios of receipts to outlays rise.19 The differences between immigrants and the native-born groups remain qualitatively unchanged, but the first generation comes closer to “breaking even”—and actually does so at the federal fiscal level in scenario 6—compared with scenarios 1 and 5.

Scenarios 3, 4, 7, and 8 adjust the first generation’s contributions of tax receipts downward either in terms of their sales and excise taxes (3 and 7) or corporate income taxes (4 and 8). The motivation for these scenarios is the recognition that some immigrants, especially new arrivals, send remittances to their country of origin rather than spending all of their discretionary income in the receiving country and that they may not yet own taxable U.S. capital assets. The scenarios that test these factors (described in Box 8-1 above) reduce tax receipts somewhat but do not drastically alter the picture. These reductions in tax receipts do little to change the relative value of the immigrant and native-born generational groups (as defined for Tables 8-1 and 8-2) in terms of their net fiscal impacts.

___________________

19 This calculation is meant mainly to serve as a sensitivity test and not to be realistic. However, debt was incurred by generations now dead as well, and an additional living person (native-born or immigrant) should not be counted as having contributed to that portion of the debt.

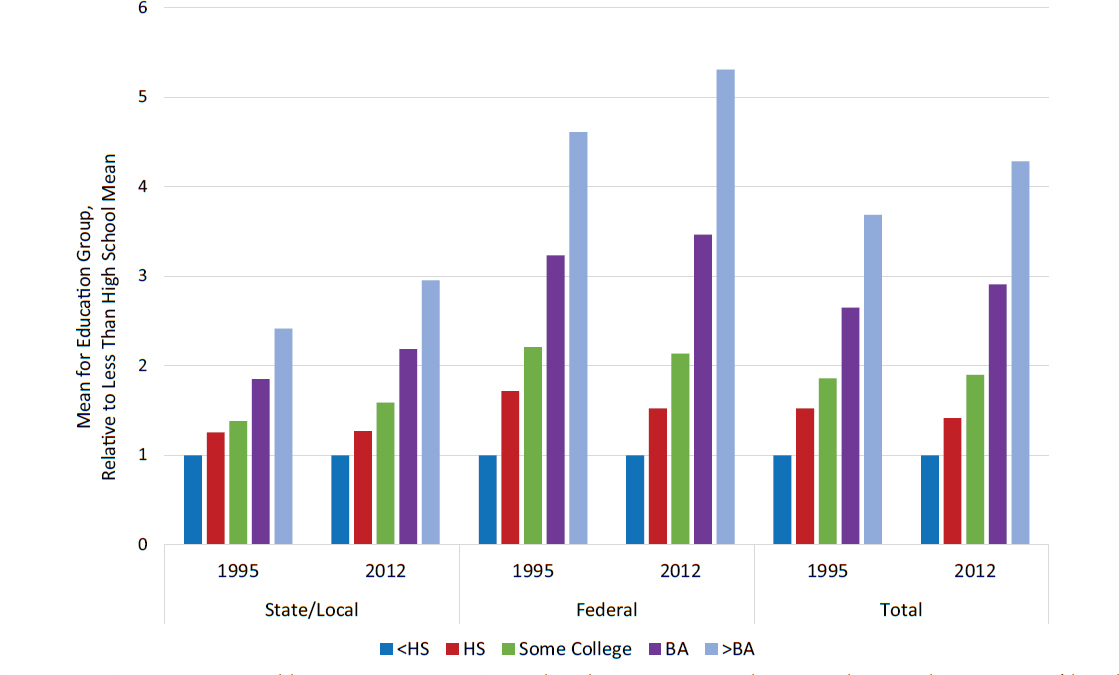

Comparing Immigrants to Natives, Controlling for Characteristics

While informative, the per capita net fiscal impacts and fiscal ratios reported thus far are associated with broad groups of individuals of widely varying age and other characteristics. As the age profiles examined earlier have suggested, the pattern, during this report’s period of analysis, of net fiscal impacts of the first generation group is shaped in large part by their disproportionate presence in the working-age and family-rearing portion of the life cycle. In the aggregate, they have made large positive contributions in the form of tax revenues (although still paying less per capita in taxes than their second and third generation counterparts—refer to Figure 8-11), while also drawing on public expenditures at higher than average rates, mainly due to the presence of more children in their households relative to native-born groups. As today’s immigrants age, as their children continue to move out of parental households, and as they themselves eventually move into retirement, their fiscal profiles will change substantially.