5

Employment and Wage Impacts of Immigration: Empirical Evidence

5.1 INTRODUCTION

The primary impact of immigrant inflows to a country is an expansion in the size of its economy, including the labor force. Per capita effects are less predictable: An injection of additional workers into the labor market could negatively impact some people in the pre-existing workforce, native- and foreign-born, while positively impacting others. The wages and employment prospects of many will be unaffected. The direction, magnitude, and distribution of wage and employment effects are determined by the size and speed of the inflow, the comparative skills of foreign-born versus native-born workers and of new arrivals versus earlier immigrant cohorts, and the way other factors of production such as capital adjust to changes in labor supply. Growth in consumer demand (immigrants also buy goods and services), the industry mix and health of the economy, and the nation’s labor laws and enforcement policies also come into play.

The primary determinant of how immigration affects wages and employment is the extent to which newly arriving workers substitute for or complement existing workers. As laid out theoretically in Chapter 4, wages may fall in the short run for workers viewed by employers as easily substitutable by immigrants, while wages may rise for individuals whose skills are complemented by new workers. For example, suppose foreign-born construction workers enter the labor market, causing a decrease in construction workers’ wages. Firms will respond by hiring more construction workers. Since additional first-line supervisors may be needed to oversee and coordinate the activities of the expanded workforce, the demand

and hence the wages of these complementary workers could receive a boost. On the other hand, where immigrants compete for the same jobs, whether as construction workers or academic mathematicians (Borjas and Doran, 2012), employment opportunities or wages of natives are likely to suffer.1 Further, where the availability of low-skilled immigrants at lower wages allows businesses to expand, total employment will rise. Wage and employment effects are predicted to be most pronounced in skill groups and sectors where new immigrants are most concentrated.

Given the potential for multiple, differentiated, and sometimes simultaneous effects, economic theory alone is not capable of producing decisive answers about the net impacts of immigration on labor markets over specific periods or episodes. The role and limitations of theory were assessed by Dustmann et al. (2005, p. F324):

Economic theory is well suited to help understand the possible consequences of immigration for receiving economies, and the theoretical aspects of the possible effects of immigration for the receiving economies’ labour markets are well understood. That is not to say that predictions of theory are clear-cut, however. It is compatible with economic models that changes in the size or composition of the labour force resulting from immigration could harm the labour market prospects of some native workers; however, it is likewise compatible with theory that immigration even when changing the skill composition of the workforce has no effects on wages and employment of native workers, at least in the long run. Economic models predict that labour market effects of immigration depend most importantly on the structure of the receiving economy, as well as the skill mix of the immigrants, relative to the resident population.

Empirical investigation is therefore needed to estimate the magnitude of responses to immigration by employers, by native-born and earlier-immigrant workers and households, by investors, by the public sector, and in housing and consumer-goods markets (Longhi et al., 2008, p. 1). Dynamic conceptual approaches are needed to assess some of the impacts of immigration, particularly those that require long periods of time to unfold.

In the context of the U.S. experience, immigrants have historically been most heavily represented in low-skilled occupations. This has prompted an extensive body of empirical work investigating whether immigration has had a negative effect on the wages and employment of low-skilled

___________________

1 Detailed discussion of when immigrant labor complements and when it substitutes for native employment can be found in Foged and Peri (2014) who analyzed relative employment effects using longitudinal employer-employee data for Denmark covering the period 1991-2008. Mouw et al. (2012) and Rho (2014) also examined this question using evidence from the Census Bureau’s Longitudinal Employer Household Data on worker displacement in high-immigration industries.

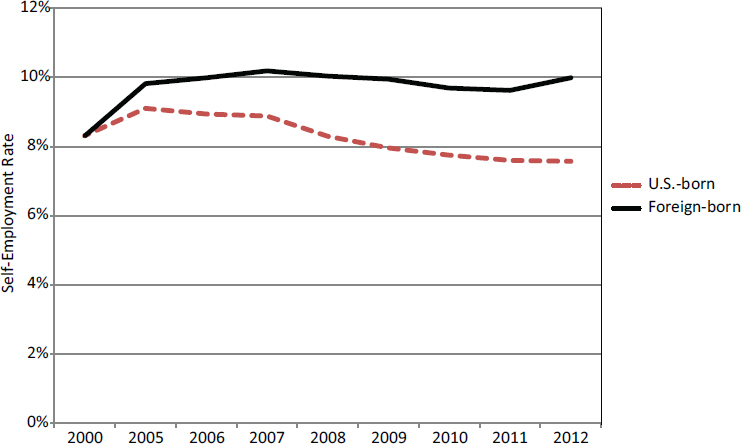

natives and earlier immigrants. However, a substantial and growing share of immigrants is highly skilled. In part because of this change—and also because of the possibility of positive spillovers from the highly skilled to other workers and to the economy more generally—this group is receiving increased attention. The panel’s summary of the literature in this chapter reviews both these strands of research: After reviewing the pivotal influence of substitutability among different labor inputs in Section 5.2, the focus of Sections 5.3 and 5.4 is predominantly on empirical analyses of low-skilled markets. Section 5.5 reports on a cross-study comparison of the magnitude of immigrants’ impacts on wages. Section 5.6 examines some of the research findings about the highly skilled, including the impact of immigration on innovation.

Given the complexity of mechanisms through which immigration shapes the economy, it is not surprising that the empirical literature has produced a range of wage and employment impact estimates. The basic challenge to overcome in empirical work is that, while wages before and after immigration can be observed, the counterfactual—what the wage change would have been if immigration had not occurred—cannot. A range of techniques has been used in the construction of this counterfactual, and all require assumptions to facilitate causal inference (i.e., identifying assumptions). The different approaches can be judged in part by the plausibility of these assumptions.

The panel has organized this review of empirical studies primarily in terms of methodological approach, using three labels common in this literature. We first describe and present results from spatial studies, which compare worker outcomes across geographic areas. Next, we review results from analyses that use aggregate (nationwide) data, including skill cell studies, which compare worker outcomes across groups defined to have similar education and experience, and structural studies, which implement the skill cell approach with a closer connection between theory and empirical estimation. Much of the discussion in these sections is concentrated on studies of the overall labor market and the low-skilled labor market. Later in the chapter, we turn our attention to evidence about high-skilled labor markets, including the effect of skilled immigration on innovation and entrepreneurship.

Spatial studies define subnational labor markets—frequently, these are metropolitan areas—and then compare changes in wage or employment levels for those with high and those with low levels of immigrant penetration, controlling for a range of additional factors that make some destination locations more attractive than others. As immigrants are likely to settle in those metropolitan areas that have experienced positive economic shocks, econometric methods are used to identify spatial variation in immigrant penetration that can be considered “exogenous”—that is, not determined

within the system being studied—with respect to the outcome that is modeled, which is typically the wages or employment of native-born workers. To illustrate, suppose an analyst is interested in identifying the impact of immigration on wages of the native-born in local labor markets. If immigrants settle predominantly in areas that experience the highest wage growth, then this will induce spurious correlation contaminating estimates of the causal effect of immigration; wage growth (or dampened wage decline) will be erroneously attributed to the increase in labor supply. An econometric solution to this problem presents itself if immigrants choose areas not just on the basis of economic conditions but also on the basis of non-economic factors, such as proximity to others with similar backgrounds. These noneconomic factors can help the analyst create variation in immigrant penetration that is independent of wage growth and that is not correlated with unobserved factors that determine wage growth. A subset of these studies has obtained identification by taking advantage of “natural experiments” created by unusual immigration events, such as the Mariel boatlift injection of more than 100,000 Cuban workers into the Miami labor market in 1980 (Borjas, 2016b; Card, 1990; Peri and Yasenov, 2015).

Another potential problem with the spatial approach, noted by Borjas (2014a), is that natives may react to an influx of immigrants by leaving affected areas, thus dissipating the labor market impacts of migration across the national economy. However, whether such responses by natives are indeed an empirical problem is controversial in the literature on immigrant inflows and native outflows (the panel considers this issue below in the review of research, e.g., Borjas, 2006; Card, 2001; Card and DiNardo, 2000; Kritz and Gurak, 2001). A more intractable problem with the spatial approach, also noted by Borjas (2014a), is that trade in goods between locales or movement of capital can also work to disperse the impacts of immigration nationally. In fact, an important insight of economic theory is that flows across localities, whether in labor, capital, or goods, will tend to diffuse the impact of immigration across the national economy, potentially making spatial comparisons less informative. To the extent that existing spatial studies have not been able to address all possible mechanisms through which local labor markets adjust, it is possible that they underestimate any impact of immigration on labor market outcomes at the national level. At the same time, economic theory also implies that domestic impacts of immigrant inflows are reduced to the extent that the United States trades with the rest of the world and that capital flows into and out of the United States (see Chapter 4).2

___________________

2 The extent to which trade serves to reduce the effect of immigration on an individual country has received attention theoretically, and these insights may apply to cross-city analyses. The classic factor price equalization model (Samuelson, 1948) holds that, if a country produces

As noted previously, the second broad category of research reviewed in this chapter focuses on aggregate (national level) data and entails dividing labor markets by skill, typically defined by years of education and experience. Borjas (2003) pioneered both the skill cell and structural approaches that comprise this line of work. In the skill cell approach, estimation relies on variation, not between geographical areas as is done in spatial analyses but between skill groups. The idea is to relate differences in immigrant inflows across the range of skill cells to differences in wage outcomes of native-born workers—just as the spatial approach relates differences in immigrant inflows across places to differences in wage growth. The drawback of this approach is that it does not estimate the entire impact of immigration. While it captures the effect on native-born workers of immigrants who have similar skills, it does not capture the effect on the native-born of immigrants who have dissimilar skills. It is unknown whether omission of these cross-group effects leads to an overestimation or underestimation of the wage impact of immigrants.

The structural approach involves assuming a particular production function describing the relationship between output and inputs (the factors of production), estimating the parameters that characterize the production technology (most notably the elasticities of substitution between factors of production), and then simulating the impact of changes in labor supply on relative wages of, say, native-born workers based on the estimated parameters and the assumed functional form of the production function.3 While, as noted earlier, all empirical approaches require identifying assumptions, structural models require particularly strong assumptions, and some of those assumptions build in specific numerical answers for the wage impact. Apart from the functional form assumptions for the production technology, as detailed in Section 5.3, results may be sensitive to assumptions about the feasibility and extent to which different inputs, such as more- and less-skilled workers or immigrants and native-born, may be substituted for one another. These assumptions are, however, necessary to reduce the dimensionality of these models in a way that makes them tractable.

Another issue for a structural approach is that predictions based on these models ignore general equilibrium effects, such as how different kinds

___________________

multiple goods that are each traded internationally, changes in relative supplies of labor of varying skills within that country need not have any effect on the relative wages by skill level within that country, provided the country is small relative to the rest of the world. On the other and, shifts in labor supplies by skill, say due to immigration, may affect relative wages if there is a significant nontraded sector or if a country specializes in one traded good (Dustmann et al., 2005; Kuhn and Wooton, 1991; Samuelson, 1948). See Blau and Kahn (2015) and Borjas (2014a) for a more extended discussion.

3 See Borjas (2014a, p. 106 ff.) for a thorough description of the constant elasticity of substitution (CES) structural modeling framework that is used in this literature.

of workers interact with each other and how investment, consumption, and other responses in the economy play out. Finally, this approach, like the skill cell approach, assumes that the analyst is able to assign immigrants and native-born workers to cells within which their education and potential labor market experience are equivalent (see Dustmann and Preston, 2012).

Not all studies fall neatly into the taxonomy described above. Both spatial analyses and aggregate skill cell and production function studies may divide workers into skill groups, and a spatial study by Peri et al. (2015a) uses city-specific production functions to estimate total factor productivity growth of U.S. cities attributable to the addition of foreign-born science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) workers. Borjas (2014a, p. 127) prescribes a strategy for future research that would combine the findings from spatial approaches—where average wage effects are estimated directly from the data—with the restrictions implied by factor demand theory to estimate cross-group effects. Though there may be some overlap and gray areas across approaches, the panel follows this categorical organization in the detailed discussion below of empirical results and then considers the lessons derived from the literature in the concluding discussion (Section 5.7).

5.2 SOME BASIC CONCEPTUAL AND EMPIRICAL ISSUES

The foregoing discussion of economists’ approaches to analyzing the impact of immigration, as well as the Chapter 4 description of relevant theory, highlights the importance of some basic concepts in determining the effect immigrants may have on native-born workers. In particular, it is clear from a theoretical perspective that the expected impact of immigration is larger in the short run than in the long run, at least if the immigration is unanticipated. In addition, whether immigrants are substitutable for natives (and how closely) or complementary with them is important for determining the direction (negative or positive) as well as the magnitude of the immigrant effects. While the theoretical concepts are reasonably clear, empirically testing them is less so. Below, the panel considers some of the empirical issues that have arisen.

The Short Run Versus the Long Run

The standard distinction between the short run and the long run in microeconomic theory is that in the short run the capital stock is fixed and cannot adjust to changes in the demand for capital. Meanwhile, in the long run, capital is completely variable and adjusts fully to changes in demand for it. With immigration, the return to capital initially rises then falls over the adjustment period, eventually returning to its original level.

Macroeconomic theory further distinguishes between a short run in which technology and education (human capital) of workers are fixed and a long run in which they adapt to changing economic circumstances. This latter conception of the long run is the focus of the panel’s discussion of immigration in an endogenous growth context in Chapter 6.

These distinctions are murkier in the real world, since these concepts do not map one-to-one with time periods of specific, consistent length. One guide to the speed at which capital adjusts is a study by Gilchrist and Williams (2004) showing that in (West) Germany and Japan, both of which suffered a large loss of capital during World War II and large population inflows immediately afterwards, the return to capital fell to world levels by the 1960s. This suggests that, for U.S. immigration purposes, capital is likely to adjust fully in considerably less than 20 years and in some cases may even be built up in anticipation of immigration. In studies of the United States, Lewis (2011a) found immigration-induced changes in the adoption of manufacturing automation equipment in a 5-year span from 1988 to 1993, while Beaudry et al. (2010) found immigration-induced changes in the adoption of computers between 1990 and 2000. These studies show that there is at least some adjustment of U.S. capital and possibly technology over 5-10 years, though it is unknown whether the adjustment observed was complete. Moreover, it might be argued that the notion of complete adjustment in the face of ongoing immigration is not clearly defined, in that there is no theory and little empirical evidence on the effect of anticipated immigration on firm behavior.

Among the various approaches reviewed in this chapter, the structural approach deals most explicitly with the distinction between the short and long run. Though the structural models are static and do not model changes over time, they yield separate short- and long-run estimates of the impact of immigration based on explicit assumptions regarding the elasticity of the supply of capital. However, technology is held fixed, and the response of worker human capital is not dealt with explicitly. Results from the spatial approach and the simple skill cell approach are more difficult to characterize along a time dimension. Presumably, estimating the effects of a large, sudden, unanticipated increase in immigration—as occurred with the Mariel boatlift—in the year or two following the inflows captures the short-run effect of immigration. More generally, the estimated effect depends on the spacing of data (e.g., decennial or yearly), the exact specification of the regressions, and the timing of immigrant inflows between the observation points; certain specifications could reflect a mixture of short- and long-run effects (Baker et al., 1999). While the panel acknowledges these ambiguities, we follow an extensive literature in continuing to use the terms “short run” and “long run,” and we grapple with the distinction as it arises in our discussion of differences in magnitudes across studies in Section 5.5.

Substitution Between Inputs and Issues in Defining Skill Groups

Economic theory points to the importance of substitutability and, conversely, complementarity between different kinds of workers in determining the impact of immigration on the wages and employment of natives.4 Where immigrants and natives are substitutes, adverse wage and employment effects may result; the more closely immigrants’ skills and abilities match those of natives, the more adverse these effects are expected to be. This raises the issue of how empirical researchers measure skill and identify groups that are potentially in competition, as well as how they model the extent of substitutability between them. Thus, we consider these issues before delving into the empirical findings on the impact of immigrant inflows on natives and prior immigrants.

Substitutability between two groups—say native workers (N) and immigrant workers (I)—is measured by the elasticity of substitution. The elasticity of substitution between natives and immigrants gives the percentage change in the ratio of immigrant workers to native workers (I/N) employed in response to a given percentage change in the wages of natives relative to immigrants (wN/wI). So, for example, an elasticity of 2 would indicate that an increase of 1 percent in the wage of natives relative to immigrants would result in an increase of 2 percent in the ratio of immigrants to native workers employed. A very high value of this elasticity implies that as the relative wage of natives rises (so natives become more expensive compared to immigrants), employers would make a more sizable switch to hiring immigrant workers—suggesting that it would be easier to make the switch. A low value of the elasticity would suggest that a similar rise in the relative wage of natives would not lead to a very large increase in the relative number of immigrants employed, suggesting that employers find it difficult to replace natives with the immigrants. If the elasticity were equal to zero, a rise in the relative wage of natives would not change the number of immigrants employed at all, suggesting that employers find it impossible to replace natives with immigrants because the two groups are not substitutable.

Substitutes may be divided into perfect substitutes and imperfect substitutes. Two groups of workers that are perfect substitutes are so nearly identical for purposes of production that an employer will be indifferent between hiring a worker from one group or the productivity equivalent number of workers from the other. One somewhat confusing aspect of this terminology is that one might be tempted to assume that perfect substitutes

___________________

4 For simplicity and also due to policy concerns, the panel frequently refers to immigrant versus native-born workers. In reality, immigrant inflows may affect the wages not only of natives but of earlier immigrants as well. Some studies have looked explicitly at the impacts of new flows of immigrants on earlier immigrants, as well as on the native-born.

are equally productive—but that need not be the case. As long as the two groups’ relative wages reflect any productivity difference between them, employers will be indifferent between hiring one or the other. The elasticity of substitution between perfect substitutes is infinite. In such a case, if the relative wage of one group were to rise, the employer would shift entirely to the other group. Imperfect substitutes are, as the name implies, substitutable in the eyes of employers but not perfectly so. The magnitude of the elasticity indicates how closely substitutable the two groups are.

In implementing this concept of substitutability, an issue that arises is how to define skill groups. As we have noted, the large representation of less-educated individuals among immigrant inflows into the United States has focused attention of researchers on the wage and employment consequences of this inflow for less-skilled natives. But how is skill to be measured? This question arises across all the approaches this report surveys and has been answered in various ways. No approach is free from some level of disagreement about this issue. In general, studies employing the spatial methodology have used education level as the metric of skill (e.g., Card, 2005), although in a few cases occupations have been used to distinguish skill groups (Card, 2001; Orrenius and Zavodny, 2007). Aggregate skill cell and production function studies generally define skill by taking into account both experience (using age as a proxy) and education to form experience-education cells (e.g., Borjas, 2003). Finally, a recent alternative for defining skill in a way that groups immigrants and natives who are competing in the labor market assumes that two individuals with the same percentile ranking in the wage distribution are viewed as close substitutes in the eyes of employers; Dustmann et al. (2013) applied this approach for the United Kingdom.

One issue that has arisen in spatial studies, as well as in aggregate production function analyses, is how to delineate educational categories. Often, four educational categories are created: (1) did not complete high school, (2) completed high school only, (3) some college, and (4) completed college. Sometimes (e.g., Borjas, 2003, 2014a) the “completed college” group is further divided into college graduates and postgraduates, yielding five categories. Some research has focused on a subset of categories—for example, examining how the inflow of low-skilled immigrants affects the wages of low-skilled natives. Recently, however, questions have been raised as to whether each educational category should be viewed as a separate factor (that is, as imperfect substitutes). Based both on his review of recent aggregate time series studies and his own analysis of spatial data, Card (2009) argued that evidence supports the conclusion that high school dropouts are essentially perfect substitutes for high school graduates. In a production function context, Ottaviano and Peri (2012) also combined the two groups, providing evidence from their data that the elasticity of

substitution is quite high, even infinite in some estimates. The treatment of these two educational categories can have significant implications. As Card (2009) pointed out, immigrants have a much higher share of high school dropouts than natives, but a fairly similar share of “high school equivalent” workers (dropouts and graduates combined, accounting for differences in productivity). Thus, the change in the skill distribution caused by an inflow of immigrants, and the resulting impact of immigration on relative wages, is smaller if the high school dropout and high school graduate categories are aggregated.5 However, aggregating the two groups is not without controversy. Borjas et al. (2012), in particular, take issue with the justification for doing so, namely the evidence on the elasticity of substitution.

The second issue of importance is whether immigrants and natives within skill groups are perfect substitutes. This issue is potentially quite important in that, for cases in which natives and immigrants are imperfect substitutes, any negative wage effects resulting from immigrant inflows will be more concentrated on previous immigrants, who are usually the closest substitutes for new immigrants, lessening the adverse impact on natives.6

Various research findings lend support to the notion that immigrants are imperfect substitutes for natives with similar measured characteristics.7Chiswick (1978) found a lower return to experience and education among new immigrants than among natives—with this experience and education presumably primarily acquired abroad. In line with Chiswick’s findings, Blau and Kahn (2015) found, for a sample of newly legalized immigrants, that education acquired abroad had a lower return than education acquired in the United States, while Akee and Yuksel (2008) found that the gap between the return to foreign versus U.S. experience is larger than that for foreign versus U.S. education. “Downgrading”8 of immigrant skills is also suggested by Akresh’s (2006) finding that, in comparing the jobs immigrants held prior to and after migrating, they typically experienced downward occupational mobility. Also relevant is Kossoudji and Cobb-Clark’s (2000) evidence of occupational upgrading of immigrants upon legalization, which suggests downgrading of unauthorized immigrants skills relative to native-born workers. Blau and Kahn (2007a) reported higher unemployment rates of Mexican immigrants (the largest single group of immigrants) relative to native-born workers with similar age and education—again suggest-

___________________

5Card (2009) advocated the formation of just two skill groups: high school equivalent and college equivalent labor. This two-group structure has frequently been used in recent aggregate time series studies.

6 See Card (2009) for a discussion; he pointed out that the difference between a large but finite elasticity of substitution and perfect substitution can be quantitatively quite important.

7 Most of this paragraph is drawn from Blau and Kahn (2015).

8 This is the term used by Dustmann et al. (2013).

ing imperfect substitution between the two groups. Finally, evidence from Smith (2012) that an inflow of immigrants with a high school degree or less reduced the employment (measured in hours worked) of native teens suggests that newly arrived adult immigrants may be closer substitutes to native teens than to their adult counterparts.9

Other work highlights the role of English-language fluency, a factor largely unaccounted for in aggregate analyses, in producing imperfect substitutability between immigrants and native-born with similar observed characteristics. Using census data on immigrant-native wage gaps for immigrants who were fluent compared with immigrants with no English, Lewis (2011b) analyzed how native-immigrant differences in language skills contribute to occupational specialization. He found that native-born workers are more represented in occupations where communication is important, which suggests that within education level, immigrants and natives may be imperfect substitutes. As the length of time spent by immigrants in the United States increases, their English improves and immigrants and native-born with comparable education become closer substitutes. In a similar vein, Somerville and Sumption (2009) found that immigrant concentration in particular industries induces natives to shift into higher paying industries where language and other native skills come into play. Likewise, Peri and Sparber (2011) investigated the role of communication skills in producing immigrant/native-born differences in occupations requiring graduate degrees. They found that the foreign-born specialize in fields demanding quantitative and analytical skills and the native-born specialize in fields where interactive and communication skills are highly valued.

Additional evidence suggesting imperfect substitution between immigrants and the native-born was provided by Ottaviano and Peri (2012). Using a structural production function approach, they estimated substitution elasticities, whose values indicate that immigrants and natives were imperfect substitutes within the typical categories used, especially among the less skilled. The production function approach they employed enabled them to take this imperfect substitutability into account in estimating wage effects. Borjas et al. (2012) challenged these findings and presented evidence that the results are sensitive to assumptions made in the estimation process.10 Moreover, while Dustmann and Preston (2012) agreed that the usual approach groups together dissimilar immigrants and natives, they

___________________

9Orrenius and Zavodny (2008) found a similar result: Minimum wage increases resulted in higher employment rates among adult immigrants while rates fell for native-born teens. The evidence therefore suggests employers switched to older foreign-born workers in lieu of native-born teens once labor costs rose.

10Borjas et al. (2012) found, for example, that the inclusion of fixed effects eliminates the finding that comparably skilled immigrants and natives are imperfect substitutes.

also took issue with Ottaviano and Peri’s (2012) method of addressing the problem.11

Spatial studies potentially have methods for handling imperfect substitutability between immigrants and natives as well. As an example, Altonji and Card (1991) estimated the link between the fraction of immigrants in the population and the wages and employment of less-skilled natives. Their specification allows any impact that immigrants with higher observable skills may have on the low-skilled native group (due to the immigrants’ imperfect substitution with higher-skilled natives) to be captured as well. It is also possible to build in adjustments to realign the way new arrivals are sorted into skill cells in these models. Orrenius and Zavodny (2007) examined the impact of immigrant penetration separately by occupational category, to allow immigrant substitutability to differ by skill. They argued that substitutability of immigrants for natives should be greater for less-skilled occupations and found results consistent with this hypothesis. In contrast, in their production function study referenced above, Ottaviano and Peri (2012) hypothesized, and found evidence, that among the highly educated, foreign-born workers are more highly substitutable for native-born workers. While these results differ, both studies found evidence of imperfect substitutability between immigrants and natives that appears to differ by skill level.

Other evidence supportive of imperfect substitutability between immigrants and natives comes from studies examining the impact of immigrant inflows on natives and prior immigrants separately. The idea here is that, if immigrants and natives are imperfect substitutes, the impact of immigrant inflows on prior immigrants should be larger than on the native-born, since immigrants are likely to be closer substitutes for each other than for natives. Many studies focus only on the native-born component of the pre-existing workforce, but when both groups are examined, larger negative wage and employment effects for previous immigrants than for the native-born are generally found (e.g., Card, 2001; Ottaviano and Peri, 2012).

Support for the view that immigrants downgrade upon arrival comes from the study noted above by Dustmann et al. (2013) for the United Kingdom. Although immigrants to the United Kingdom have typically had

___________________

11 Specifically, Dustmann and Preston (2012) argued that a key assumption in the Ottaviano and Peri (2012) approach is that immigrants and natives can be allocated to age-education cells within which their potential experience and education are comparable. This may, however, not be the case, as immigrants may—at least initially—downgrade, which means they compete with natives in segments of the labor market other than where one would expect them based on their observed education and potential experience. This will cause a bias in the estimates of the elasticity of substitution between immigrants and natives. Due to downgrading, immigrants and natives may appear to be imperfect substitutes even though, if correctly classified, they are not.

more education on average than native-born workers, they have fallen disproportionately at the lower end of the wage distribution. This finding, the authors claimed, has serious consequences for approaches that rely on preassigning immigrants to skill cells based on their observed age and education, within which they are assumed to be equivalent in production to natives.

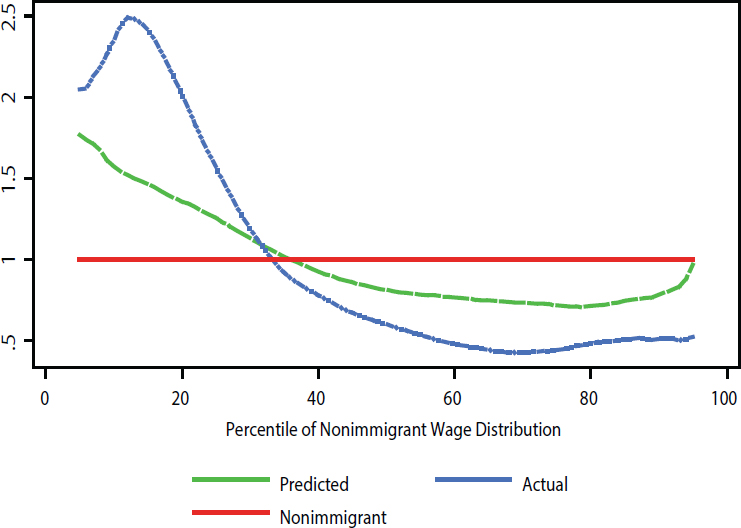

Data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) indicate that downgrading is also an issue in the United States, although to a lesser extent. Figure 5-1 (from Dustmann and Preston, 2012) shows the predicted position, based on age and years of schooling, and the actual position of recent immigrants relative to the native-born wage distribution. The short-dashed line in the graph (labeled “actual”) indicates that recent immigrant workers are more concentrated in the lower quintiles and less concentrated in the

NOTE: The vertical axis represents densities—the continuous equivalent of probabilities. One can interpret the vertical axis as giving the probability of immigrant workers being in one specific percentile of the native wage distribution. The curve labeled “actual,” then, is not the probability of being in a given wage percentile relative to natives but rather the probability of being in a given percentile of the native wage distribution.

SOURCES: Dustmann and Preston (2012, Fig. 1b, p. 222). Original graphic based on Current Population Survey data, 1997 to 2007.

higher quintiles of the native wage distribution than would be predicted by their age and education profiles (the horizontal line is the reference indicating the nonimmigrant wage distribution; the long-dashed line is where one would predict immigrants to be located along the distribution of native wages if they received the same return on labor for their observed education and experience as natives did). Elsewhere in their paper, Dustmann and Preston (2012) showed that downgrading is strongest just after arrival (the period reflected in the graph); they found that over time, immigrants to the United Kingdom catch up to the occupations and wage levels predicted by their education.

Based on observations like these, Dustmann et al. (2013) argued against estimators that require the preallocation of immigrants to skill groups, arguing that this may not lead to meaningful estimates because immigrants may compete with native-born workers at other parts of the skill distribution than those to which one would assign them based on observed characteristics. Using a spatial approach, they proposed an estimator that does not rely on preallocation of immigrants to skill groups but instead regresses skill-group-specific native wages (in their approach, defined as percentiles of the wage distribution) on the overall inflow of immigrants. The resulting estimates have a straightforward interpretation and are not affected by downgrading.

While there is indeed suggestive evidence that immigrants and natives may be imperfect substitutes within skill groups defined by measured characteristics, there remains controversy regarding whether this is an important issue for empirical analyses and how it should be dealt with. The panel considers this issue further, along with the appropriateness of aggregating high school dropouts and high school graduates, in the context of the studies reviewed below.

5.3 SPATIAL (CROSS-AREA) STUDIES

In the pioneering work by Grossman (1982) on the “substitutability of immigrants and natives in production”—a paper that influenced much of the subsequent research—labor market boundaries were defined as metropolitan areas. Intuitively, since immigrants choose some destinations with greater frequency than others, comparing wage and employment trends across metropolitan areas should yield evidence about the impact of their arrival. As described above, the methodology involves testing whether native wage growth and employment rates in the high-immigration areas are lower than those in the low-immigration areas.12 The earliest studies relied solely on cross-sectional variation, while later work, beginning notably with Altonji

___________________

12Card (2005) describes the spatial approach in detail.

and Card (1991) and including most of the studies summarized here, recognized and attempted to deal directly with the endogeneity problem inherent in this approach: The magnitude of immigrant flows into an area is likely to be correlated with its economic vitality and wage growth.

Studies relying on geographic labor market variation are listed and compared in Section 5.8, Table 5-3. In considering the results of these studies, a useful starting point is the assessment of evidence presented 20 years ago in The New Americans (National Research Council, 1997). For the literature surveyed in that report, with the exception of Altonji and Card (1991), the estimated coefficient indicating the sensitivity of native-born wages to an increase in immigrants in a given local labor market was closely clustered around zero. The New Americans reported:

The evidence also indicates that the numerically weak relationship between native wages and immigration is observed across all types of native workers, white and black, skilled and unskilled, male and female. The one group that appears to suffer significant negative effects from new immigrants is earlier waves of immigrants, according to many studies. (National Research Council, 1997, p. 223)

As documented below, however, continued study of this issue over the past two decades has led to greater variation and detail in estimates of the wage impacts of immigration obtained from the local labor market approach.

Comparing the experiences of high-immigration and low-immigration geographic areas has a great deal of intuitive appeal. The concept is easy to understand. Blau and Kahn (2015, p. 813) outlined the advantages of the approach:

. . . the empirical work directly ties the key explanatory variable, immigration, to the outcomes of interest. No assumptions about how labor and other inputs combine in production processes need be made. In particular, one need not assume or try to estimate the degree to which immigrants and natives of equal observed skills substitute for each other, although such a relationship will influence the parameter estimates. In addition, using the area approach will provide more potential observations than using national aggregates, producing more efficient estimates.

The analytic challenges to spatial studies have to do with the endogenous factor flows and trade flows that potentially bias the estimates of cross-area wage differentials.13Borjas (2014a), Blau and Kahn (2015), and

___________________

13 This is also an issue for aggregate skill cell and production function models, discussed in Section 5.4, albeit possibly a lesser one. As explained by Llull (2015), immigrants to the United States do not display random experience levels (ages) and education.

others, as noted below, identified these challenges: (1) Immigrant flows are not randomly distributed across metropolitan area labor markets. As noted above, new arrivals are likely to select areas at least near those that are thriving economically14—that is, those experiencing wage and employment growth (e.g., California or Florida in the mid-to-late 1990s). This area-selection bias creates spurious, positive correlations between immigration to an area and that area’s employment conditions and relative wages. (2) Local labor markets are not closed, which means that natives (or earlier immigrants) are free to relocate their labor (and capital), which may at least partially equilibrate prices and quantities across markets defined by geographic areas. As possible evidence of this problem, Borjas et al. (1997) showed that, for the 1980-1990 period, the correlation between inflows of low-skilled immigrants and the wages of low-skilled natives was more negative, the larger the geographical area demarcated (regions versus states or states versus metropolitan areas). Similarly, Borjas (2003) included analyses by geographical areas (i.e., states) that reveal smaller negative effects on a skill group’s earnings from an immigrant inflow than did the national level estimates. (3) Trade in goods between areas will tend to equalize factor prices, including wages, across areas, in a process known as factor price equalization. Finally, models for which the key independent variable (immigration) is measured for small geographic areas with small samples are susceptible to measurement errors, greatly attenuating the measured impact of immigration (Aydemir and Borjas, 2007).

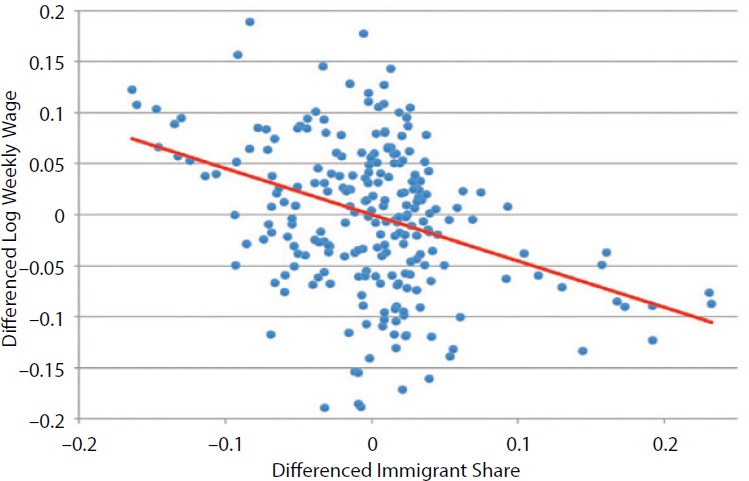

Endogeneity of Change in Immigrant Share and Labor Market Performance

The above complications associated with estimating cross-area wage and employment effects make it difficult to establish causal links. Regarding the endogeneity challenge, the question is: To what extent do immigrant inflows affect wages and employment and to what extent do wage and employment conditions influence immigrant inflows? Either could explain an observed correlation, and both probably occur to some degree in any given case. Indeed, Cadena and Kovak (2016) showed that low-skilled immigrants have settled in those cities that offer the highest wages, leading to a positive correlation between wage growth and immigrants’ location decisions. If new arrivals migrate to strong economies that are already experiencing high or rising wages, measured negative effects of immigration

___________________

14 Mainly due to housing, immigrants are often priced out of the most economically thriving neighborhoods within a metropolitan area (Saiz, 2008). For this reason, analyses at, for example, the census tract level may produce quite different results from those at the Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) or state level.

will be understated unless this counterbalancing influence is accounted for. Conversely, immigration may decline in response to relatively slow wage growth in areas that are economically depressed. Monras (2015) found that, during the Great Recession, “fewer people migrated into the locations that suffered more from the crisis.” This relative shrinking of the labor supply in the most hard-hit metropolitan areas would have alleviated some of the negative wage effects associated with the crisis by spreading the local recession shocks across regions or nationally.

As noted above, this endogeneity problem may be overcome by isolating the variation in immigrant inflows across areas that is neither determined by outcome variables (such as area wages) nor affected by the same unobserved factors that influence wages. The common approach to doing this is to find a variable (or a set of variables) that (1) is correlated with the inflow of immigrants to an area, but (2) is not correlated with factors that determine the growth of wages, other than through the inflow of immigrants. Such variables are called “instrumental variables” (IVs) or just “instruments.” While (1) is an empirical question, and can be tested, (2) is untestable and has to rely on the plausibility of the assumptions under which it is valid. The quality of the study depends therefore on the degree to which the assumptions underlying (2)—called exclusion restrictions—are plausible.

It can be difficult to find instruments that are highly correlated with the inflow of foreign-born workers into a local labor market yet uncorrelated with the other factors that determine wages or job growth in that area. The most common IV strategy, introduced by Altonji and Card (1991) and further developed by Card (2001), relies on the observation that immigrants tend to locate where there are already settlements of their co-nationals (see Bartel, 1989). Reasons suggested for this tendency include the possibility of drawing on preexisting networks, informational advantages, and access to cultural goods that are difficult to obtain without access to co-nationals. While past concentrations of individuals from one’s own country are likely to be correlated with future inflows to a particular area, they are at the same time unlikely to be correlated with future area-specific shocks that affect wages and employment. Based on this line of reasoning, the approach then allocates the overall inflow of immigrants from a particular country to spatial areas based on historical settlement patterns. For example, suppose the United States consisted of a Southern part and a Northern part only; assume further that, in 1980, 10 percent of all immigrants from Mexico lived in the North, while 90 percent lived in the South. Now suppose that 100,000 Mexicans arrived between 1999 and 2000. Based on the historical settlement pattern in 1980, this approach would assign 10,000 to the North and 90,000 to the South. Doing the same assignment process for all immigrant groups and summing up for each region results in an estimate

of the area-specific inflow of immigrants between 1999 and 2000 that is solely based on historical settlement patterns and is unlikely to be correlated with contemporaneous (i.e., 1999-2000) area-specific shocks to wages and employment.

One possible problem with this approach is that economic characteristics that initially made an area attractive to immigrants may persist over time. For example, if traits of the economy driving both economic growth and migration in gateway locations such as California or New York have systematically differed from other regions over many years, the downward impact of immigration on wages may still be masked. However, as Blau and Kahn (2015) noted, the finding by Blanchard and Katz (1992) that the wage effects of local employment shocks die out within 10 years provides some support for the interval, employed in most of these studies in the construction of the instrument, of 10 or more years between the previous immigrant concentrations used to derive the allocation and the current inflows.15

Due to concerns about whether local labor market conditions during the analysis period are, or are not, directly related to conditions for the period from which the instrument is constructed, researchers have begun exploring alternative instruments. For example, an IV constructed to deal with endogeneity of location choices may be based on a characteristic such as the distance between origin and destination countries. In a skill cell study based on cross-national comparisons, Llull (2013, p. 2) used variation in “push factors . . . interacted with distance to the destination country in order to construct an instrument based on variation over time and across destination countries.” So, for example, violence in Guatemala would be expected to increase migration to Mexico or the United States at a greater rate than to Europe. Llull further broke out variation by skill level, based on the assumption that destination choices will be more constrained for low-skilled workers because, compared with high-skilled workers, they have fewer resources to travel long distances.

Native Response to Immigration, Trade, and Technology Adjustments

Mobility of labor, capital, and goods between areas gives rise to a second analytic challenge for spatial studies. Cities and states are not closed economies, meaning that labor and capital flow from one to another, and these flows have the capacity to equalize prices.16 If immigrants were to

___________________

15Borjas et al. (1997) attempted to address this issue by controlling for pre-existing population trends. See also Dustmann et al. (2005) for the United Kingdom.

16 Price equalization pressure would also happen in the presence of trade even if labor and capital were immobile—see below and the theory discussion in Chapter 4. This is important because sometimes papers find that labor is not that mobile and mistakenly conclude that therefore prices are not equalizing.

arrive in disproportionate numbers in a city (or neighborhood, or whatever spatial unit defines the labor market), it is possible that some workers previously there may respond by moving elsewhere, which would diffuse the downward pressure on wages across cities:

. . . natives may respond to the wage impact of immigration on a local labor market by moving their labor or capital to other cities. These factor flows would re-equilibrate the market. As a result, a comparison of the economic opportunities facing native workers in different cities would show little or no difference because, in the end, immigration affected every city, not just the ones that actually received immigrants. (Borjas, 2003, p. 1338.)

In such a scenario, a comparison of wages across cities would reveal little, if any, wage effect.

While predicted by theory, evidence of the equilibrating hand of factor input mobility—specifically, native migratory response to increased job competition—is mixed. On one side, Card (2001), Card and DiNardo (2000), Kritz and Gurak (2001), and Peri (2007) found, for the U.S. context, either no relationship between the entry of immigrants and the exit (or failure to enter) of the native-born or that both immigrants and the native-born moved to the same cities and probably for the same reason: economic opportunity. Economically healthy cities, for example, likely attract inflows of both international and domestic migrants. These results suggest that outflows of natives may not significantly contaminate estimates of immigrant effects based on regional variation.

The evidence on the other side, for factor input mobility, includes Borjas (2006), who used Decennial Census data for the period 1960-2000 to show that internal migration decisions by natives are sensitive to immigrant-induced increases in labor supply. Specifically, high-immigration areas were associated with lower native in-migration rates and higher native out-migration rates. Native migration responses, in turn, “attenuate the measured impact of immigration on wages in a local labor market by 40 to 60 percent, depending on whether the labor market is defined at the state or metropolitan area level” (Borjas, 2006, p. 221). Some heterogeneity in responses has also been detected. For example, Kritz and Gurak (2001) found minimal overall connection between in-migration of foreign-born and out-migration of native-born, but they also found that the results varied by state and by group. They found a positive relationship between immigration and native out-migration for California and Florida and also found that, in states that have experienced the highest immigration, foreign-born men were more likely to out-migrate than were native-born men. That is, prior immigrants were more mobile than natives. Partridge and Rickman (2008) found out-migration responses to immigration to be more significant

in rural counties. In addition, they found that previous interstate movers (immigrant or native-born) were more likely to move from states with high recent immigration than either immigrants living in their state of first settlement or natives living in their state of birth.

A similar masking of cross-area impacts could occur due to intercity and interstate trade. Card (2005, p. 10) noted that, in the presence of trade across cities, “relative wages may be uncorrelated with relative labor supplies, even though at the national level relative wages are negatively related to relative supplies.” If low-skilled international immigrants move to Los Angeles, for example, the production of goods intensive in low-skilled labor will increase there. However, the prices of these goods in Los Angeles may not change compared to other cities because free trade within the United States ensures prices are equalized across cities and regions, and so are wages (which is the factor price equalization theorem). This means that so long as technology does not change, relative wages of low-skilled workers in Los Angeles compared to other cities will not change either. This logic holds as long as the inflow of immigrants is not so large that Los Angeles ceases to produce goods intensive in higher-skilled labor and comes to specialize in low-skilled intensive goods;17 in this case, relative wages of low-skilled workers in Los Angeles could indeed fall compared to other cities. These results are also contingent on there not being a significant nontraded sector and on Los Angeles producing just a small share of low-skilled intensive goods produced nationally.

In sum, any type of labor market response to immigration—whether along the margin of labor flows, capital flows, or flows of goods—can serve to diffuse the impact of immigration from the localities directly affected to the national economy. This kind of diffusion implies that even though one may not observe adjustments along a particular margin, there may be other unexamined and unexplored margins along which such adjustments can take place. Any such adjustments imply that spatial correlations between wages and immigration may underestimate the national wage impact of immigration.

The adjustments described thus far in this section explain why spatial studies may underestimate any national wage impact of immigration. However, the same reasoning implies that there are other adjustments—international trade in goods and services and capital flows across countries—mitigating the wage effect of immigration at the national level. Imports and exports of goods and services together represented 30.0 percent of U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) in 2014, indicating that the United States is well integrated in world trade. Along with large capital flows between

___________________

17 See Section 4.5 for discussion illustrating these relations in a simple model with two types of labor and two types of production technologies.

the United States and foreign countries, this trade may prevent or limit any wage response to immigration, though this is difficult to study empirically.

The ability of firms to change their technology is another factor possibly dampening negative wage impacts of immigration. The basic idea is that firms adjust technology to absorb workers who become more abundant through immigration (see Section 4.5). Similar to the situation with trade, this adjustment can lead to a situation where an immigration-induced labor supply shock is absorbed without changes in wages.18Hanson and Slaughter (2002) were among the first to compare the trade- and technology-induced adjustments to labor supply shocks on the industry level, while Dustmann and Glitz (2015) extended this literature by investigating adjustments at the firm level and considering the role of firm births and deaths in the adjustment process. Both papers found that technology-induced changes in factor intensity are more important for the absorption of immigration than trade-induced changes in the mix of outputs (see also Lewis, 2013). Lewis (2011a) focused on the technology explanation and examined how investment in automation machinery by U.S. manufacturing plants over recent decades has substituted for different kinds of labor. He concluded that “these investments substituted for the least-skilled workers and complemented middle-skilled workers at equipment and fabricated metal plants.” He found that metropolitan areas that experienced faster growth in the relative supply of less-skilled labor as a result of immigration “adopted significantly less machinery per unit output, despite having similar adoption plans initially [implying that] fixed rental rates for automation machinery reduce the effect that immigration has on less-skilled relative wages” (Lewis, 2011a, p. 1029).

Illustrative Results from Spatial Studies

Table 5-3 in Section 5.8 summarizes the results from spatial studies of the labor market effects of immigration, most of which employed IV methods to address the endogeneity of immigrants’ locational choices. While these studies are not uniform—they use different data, look at different time periods, and examine varying magnitudes of immigrant inflows—their results suggest that the impact of immigration on the group most likely to be affected, low-skilled workers, ranges from negligible to at least modestly negative. A more precise comparative assessment of the literature is provided in Section 5.5 below. As noted above, some groups such as prior

___________________

18 In terms of a standard model of production, this interpretation refers to a change in relative inputs due to a technology-induced rotation of the isoquant around a fixed isocost line, while the trade explanation above refers to a situation where relative inputs (i.e. shares of low-skilled to high-skilled labor) change due to the isocost line rotating around a fixed isoquant.

immigrants—for example, the Hispanic immigrants and Hispanic native-born studied by Cortés (2008)—appear to experience somewhat larger negative wage impacts. One contributing factor to the differential wage impact experienced by Hispanics, identified by Warren and Warren (2013) and Massey and Gentsch (2014), is that these groups are often competing in labor markets characterized by a rising share of unauthorized workers who are under increasing enforcement pressure. This may reduce their bargaining power and create downward pressure on wages in those labor markets. Employment impacts, measured in various ways discussed below, are also modest but perhaps vary more broadly across metropolitan areas.

Spatial studies commonly designate the skill group of natives, and sometimes immigrants, according to education level, although some use occupation as the skill dimension. Given the composition of immigrants relocating to the United States historically, the focus has generally been on their impact on low-skilled or other disadvantaged groups. The important study by Altonji and Card (1991) is an example. The IV approach used in most subsequent studies had its beginnings in this study and was later further refined in Card (2001). In Altonji and Card (1991), the 1970 share of immigrants in the population was used to construct the IV for immigrant inflows over the 1970-1980 period. As discussed above with regard to the possible imperfect substitutability of immigrants and the native-born with similar measured characteristics, focusing on the total immigrant share implicitly allows cross-effects to be examined. However, it does not allow an analysis of which immigrants are having the largest impact and instead measures the average effect.19

Overall, Altonji and Card (1991) found that immigration had a negative effect on wages, with a 1 percentage point increase in the immigrant share of the population reducing wages of low-skilled, native-born workers by 1.2 percent. They also found that a 1 percentage point increase in a city’s foreign-born share predicted a reduction in the earnings of black males with a high school degree or less by 1.9 percent, black females with high school or less by 1.4 percent, and smaller—and statistically insignificant—reductions in earnings for whites with a high school education or less. The only other spatial study that found negative wage effects of similar magnitude is Borjas (2014a); the panel discusses below why these results might differ from those of other studies. Regarding employment (as opposed to wage) effects, Altonji and Card (1991) found that immigration

___________________

19 For example, two cities may have the same share of immigrants but in one city immigrants may be predominantly high skilled and in another predominantly low skilled. As explored in Section 4.5, the estimated effect of the immigrant share variable may be smaller than if the effect of immigrant shares of low-skilled and high-skilled immigrants on their native counterparts were separately examined.

over the 1970-1980 period in low-wage industries led to modest displacement of low-skilled natives from those industries; but they found no statistically significant reduction in low-skilled natives’ weeks worked or the employment-to-population ratio.

LaLonde and Topel (1991) examined the impact of recent immigration on different arrival cohorts of prior immigrants. Their results are notable for identifying a negative relationship between new inflows and the earnings of recent prior immigrants—an effect that appeared to diminish with the amount of time prior immigrants had spent in the United States. In addition, they characterized the estimated effect of immigrants on the wages of nonimmigrants as “quantitatively unimportant” (Lalonde and Topel, 1991, p. 190). While they did not instrument for immigrant inflows, potentially underestimating the negative effect of immigrants, their findings are consistent with evidence discussed above of imperfect substitution between immigrants and native-born workers.

Since immigrants were disproportionately (relative to native-born workers) in the low-skilled category in the time periods examined, researchers expected larger impacts of immigration on the wages of low-skilled native-born blacks than whites because among low-skilled workers, native-born blacks are less skilled and otherwise disadvantaged compared to native-born whites. As noted above, Altonji and Card (1991) found adverse wage effects that were larger for blacks than whites. LaLonde and Topel (1991) also reported a negative effect for young (and hence inexperienced) native-born blacks, finding that a doubling in the number of new immigrants would decrease wages by a very modest 0.6 percent for young native-born black workers. Other studies for this period (e.g., Bean et al., 1988; Borjas, 1998) did not detect an effect for native-born black workers. Original analysis of Decennial Census data in The New Americans suggested that one reason for this minimal measured impact was that—as of the mid-1990s—immigrants and the black population still largely resided in different geographic locations and therefore were not typically in direct competition for jobs (National Research Council, 1997, p. 223). Until recently, large proportions of the nation’s immigrants were concentrated in relatively few geographic areas, making the distinction between high- and low-immigration areas somewhat intuitive. However, relative to 20 or even 10 years ago, immigrants are now much more spatially diffused, so one should not assume that these historical relationships continue to hold.

Returning to the question of the impact of immigration on the wages of less-skilled natives, subsequent studies by Card (2001, 2005, 2009) concluded that—in line with previous findings other than Altonji and Card (1991)—the impact of immigration on the wages of less-skilled natives was modest for the various time periods considered in these studies. The Card studies all use instrumental variables to address endogeneity of immigrant

inflows, and in Card (2001, 2009) the issue of native out-migration was addressed and found not to play a role. Card (2005, 2009) raised the possibility that high school dropouts and high school graduates are perfect substitutes as an explanation for these small wage effects. As noted above, if this is the case, then the skill distribution of immigrants is quite similar to that of natives and hence large negative wage effects on low-skilled natives are not expected.

While most studies in the spatial literature use education to define skill, it is noteworthy that Card (2001) and Orrenius and Zavodny (2007) focused instead on occupation. The former separated the labor market into different metropolitan areas and, within metropolitan areas, into different occupation groups. Immigrants’ inflows into cells defined by occupation and metropolitan area were predicted for each immigrant source country based on (1) the share of earlier immigrant cohorts from the source country living in the metropolitan area and (2) the national share of immigrants from the source country in each occupation. Card then summed over source countries to obtain the instrumental variable for immigrant inflows into these occupation-metropolitan area cells.20 The basic finding of this study was that immigration during 1985-1990 reduced real wage levels by at most 3 percent in low-skilled occupations in gateway U.S. metropolitan areas characterized by the highest immigration levels. Results varied by group: a 10 percent labor supply increase due to immigration (implying a much larger percentage increase in the number of immigrants) was associated with a wage decline of 0.99 percent for male natives and 0.63 percent for female natives, a decline of 2.5 percent for earlier female immigrants, and a change indistinguishable from zero for earlier male immigrants. It is notable that the largest negative effects were for an immigrant group. On the employment side, Card (2001, p. 58) found “relatively modest” effects of recent immigrant inflows on workers in the bottom of the skill distribution in “all but a few high-immigrant cities.” A 10 percent labor supply increase was found to have reduced the employment rate by 2.02 percentage points for male natives, by 0.81 points for female natives, by 0.96 points for earlier male immigrants, and by 1.46 points for earlier female immigrants.

Orrenius and Zavodny (2007) used a panel model with instrumental

___________________

20 That is, what Card termed the “supply-push component” of immigrant inflows for group g into occupation group j and city c (SPjc) is:

SPjc = ∑gτgjλgcMg,

where Mg represents the number of immigrants from source country g entering the United States between 1985 and 1990; λgc is the fraction of immigrants from an earlier cohort of immigrants from country g who live in city c in 1985, and τgi is the national fraction of all 1985-1990 immigrants from g who fall into occupation group j.

variables to estimate wage impacts of immigration on natives, also by occupation group. The authors found a small negative effect on the wages of low-skilled natives and no wage effect in more-skilled labor markets. A variable quantifying “immigrants who are admitted to the United States in a given year as the spouse of a U.S. citizen by occupation group, area, and year” works as the instrument because it is correlated with the rate of immigration into a given Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) and occupation but is uncorrelated with unobserved factors that drive wage growth (Orrenius and Zavodny, 2007, p. 11).

Smith (2012) examined spatial variation in employment for a narrowly defined group of workers under the hypothesis that new immigrant workers often compete in very specific labor markets. Also employing an IV model based on the geographic preferences of previous immigrants, he found that low-skilled immigration since the late 1980s had negatively impacted youth employment more than less-educated, native-born adult employment. He estimated that a 10 percent increase in the number of immigrants with a high school degree or less reduced the “average total number of hours worked in a year by around 3 percent for native teens and by less than 1 percent for less-educated adults.” This finding adds a new detail to the previous research that generally found modest negative or no relationship across states or cities between intensity of immigration and adult labor market outcomes across metropolitan areas or states (e.g., Card, 1990, 2001; Lewis, 2003). Smith (2012, p. 55) suggested that two factors were at work, “There is greater overlap between the jobs that youth and less-educated adult immigrants traditionally do, and youth labor supply is more responsive to immigration-induced changes in their wage.” His empirical analysis also suggests that, despite modest increases in schooling rates of natives in response to immigration, there is little evidence of higher earnings 10 years later in life. Smith concluded that it is possible “an immigration-induced reduction in youth employment, on net, hinders youths’ human capital accumulation.”

Other recent studies also suggest larger negative effects of immigrant inflows on earlier immigrants than on natives, consistent with LaLonde and Topel’s (1991) earlier findings and the notion of imperfect substitution between the two groups. Cortés (2008) examined the impact of immigrant inflows over the 1980-2000 period in immigrant-intensive predominantly service industries, following Card’s approach of instrumenting immigrant inflows using previous settlement patterns. Similar to Card, she found that low-skilled immigration does not have an effect on low-skilled native wages overall. She did, however, find a modest negative impact on the wages of low-skilled previous immigrants and low-skilled native-born Hispanics, especially those with poor English. Complementary findings by Lewis (2013) indicate that among immigrants, the wages of those with poor English skills are more

sensitive to immigrant inflows than the wages of those with good English skills. This evidence suggests that language skills may be a significant factor influencing substitutability between immigrants and natives with the same observed characteristics.

Natural Experiments

Sometimes “natural experiments” arise that provide unique opportunities to deal with the endogeneity problems inherent in spatial analysis. Such experiments also provide an opportunity to study the short-run effect of abrupt, unexpected immigration episodes, which should yield the most negative impacts on natives. An example is the pioneering work by Card (1990), who took advantage of one such case—the 1980 Mariel boatlift, which brought thousands of predominantly low-skilled Cuban immigrants (referred to as “Marielitos”) to Miami, expanding that area’s labor force by about 7 percent in just a few months. This circumstance allowed for a well-controlled analysis: Card was able to estimate the impact of this immigration episode by comparing wage and employment changes after the influx in Miami with wage and employment changes in otherwise similar metropolitan areas that did not experience this influx. The endogeneity problem confronting spatial analyses was avoided altogether because the arrival of the Marielitos to Miami had nothing to do with selection of a high wage destination. Card’s study was one of the first to use the identification strategy that became known as the “difference in difference” approach: comparing differences in wages or employment between Miami and other metropolitan areas, and over time. However, it still entails an important assumption—that, in the absence of the Mariel boatlift, wages and employment in Miami would have developed in similar fashion as in the comparison metropolitan areas (the “common trend assumption”).

Using this approach, Card (1990) found that, while the unemployment rate among black workers rose in the 2 years after the Marielito influx into the labor market, the rise was not significantly different from that experienced in four comparison cities (Atlanta, Houston, Los Angeles, and Tampa-St. Petersburg, chosen because of similar racial profiles and employment trends). One explanation Card provides is the flexibility of the Miami labor market in absorbing low-skilled workers by expansion of industries that produce goods that use low-skilled workers more intensively. In this study, the comparison cities substitute for the missing counterfactual: namely, what would have happened if the immigration had never taken place.

First, Borjas (2016b) and Peri and Yasenov (2015) have recently reappraised the Mariel boatlift immigration episode, carefully matching the skills of the arrivals with those of the pre-existing workforce. The skill-matching technique led them to focus on the impact on non-Hispanic (Borjas)

and non-Cuban (Peri and Yasenov) high school dropouts because high school dropouts represented about 60 percent of those arriving on Florida’s shores as a result of Castro opening the port of Mariel. The available data do not permit natives and immigrants to be distinguished, but Miami had few non-Hispanic immigrants at that time. Both papers were motivated in part by the development of a new technique (Abadie et al., 2010) to select comparison cities more systematically than did Card. Despite this methodological similarity, the authors reach very different conclusions. Peri and Yasenov concurred with Card, finding no detectable negative effects on wages of non-Cuban workers. Borjas found that a drop, in the range of a 10 to 30 percent decrease, in the relative wage of the least educated Miamians occurred between 1979 and 1985, representing a shock that took the better part of a decade to absorb. The divergent results in the two studies are due in large part to the composition of the samples and data sources examined to analyze wage trends in post-Mariel Miami and the comparison cities.

The misalignment of the study results described above suggests that differences in the implementation of a methodology can result in quite different estimates of the impact of immigration. Consideration of these studies also underlines that what occurred to the wage structure in Miami was a very unusual event—one that can be characterized as a true short-run shock occurring in a compressed time period, as opposed to more-anticipated immigrant flows that typically occur over longer time periods. The decade-long absorption of the supply shock in the Miami labor market was a unique episode and may not be fully informative about the dynamics of how labor markets in general adjust to immigration.

Monras (2015) exploited a different natural experiment. The Mexican peso crisis caused that country’s GDP to contract by 5 percent in 1995, leading to a surge in Mexican immigration to the United States for reasons unrelated to changes in the U.S. economy. This event allowed Monras to estimate a short-run effect by comparing wage data for 1994 and 1995 using the CPS. Unlike in the Mariel boatlift case, this natural experiment did not direct immigrants to a particular location in the United States, so Monras used the usual IV for immigrant location based on the 1980 settlement pattern of Mexicans. He found that a 1 percent increase in labor supply due to the immigration of Mexicans with an education of high school or less reduced the wages of pre-existing non-Hispanic workers with an education of high school or less by 0.7 percent. The pre-existing workers in this sample include non-Hispanic immigrants. The observed effect is less negative than that observed by Altonji and Card (1991) but more negative than those observed by Card (1990) and Cortés (2008). Monras found that internal migration caused most of the effect to dissipate within 10 years.

Using a natural experiment approach in the study of immigration is quite attractive, although, as one can see in our discussion of the impact

of the Mariel boatlift, the results are still not free from disagreement. It would certainly be of considerable interest to have a number of such studies for the United States. But, by its nature, this type of exogenous inflow of immigrants is a rare occurrence. While the panel’s review in this chapter is focused on empirical evidence for the U.S. experience, in this case, given the paucity of data for the United States, it is worth noting evidence from other countries where natural-experiment situations have arisen.