4

Health Literacy in Precision Medicine Research

The workshop’s second panel session comprised three presentations on different ways in which health literacy plays a role in precision medicine research. Suzanne Bakken, the Alumni Professor of Nursing and a professor of biomedical informatics at Columbia University, spoke about the recruitment of research subjects and issues of privacy and consent. Consuelo Wilkins, the executive director of the Meharry-Vanderbilt Alliance, discussed engagement and retention. Paul Appelbaum, the Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law and the director of the division of law, ethics, and psychiatry at Columbia University, addressed the reporting of results. Marin Allen, the deputy associate director for communication and public liaison and the director of the Public Information Office at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and Benjamin Solomon, the chief of the division of medical genomics at Inova Translational Medicine Institute, then provided their reactions to the three presentations. Their comments were followed by an open discussion moderated by Laurie Myers, the director of global health literacy at Merck & Co., Inc.

HEALTH LITERACY, INFORMED CONSENT, AND COMMUNICATING WITH RESEARCH PARTICIPANTS1

The Washington Heights/Inwood Informatics Infrastructure for Comparative Effectiveness Research (WICER) project is aimed at developing the

___________________

1 This section is based on the presentation by Suzanne Bakken, the Alumni Professor of Nursing and a professor of biomedical informatics at Columbia University, and the statements have not ben endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

informatics infrastructure for comparative effectiveness research, and, as Bakken explained, it can provide a foundation for the Precision Medicine Initiative (PMI). WICER was inspired by the Framingham Heart Study and shares a focus on cardiovascular disease with that study, but it was conducted in a largely Latino immigrant community in the northernmost section of Manhattan with significant health disparities. A unique feature of this study, Bakken said, was the availability of data from a variety of sources, including Columbia University Medical Center, the Visiting Nurse Service of New York, a skilled nursing facility in the area, and a community-wide survey. The initial goals for the project, Bakken said, were to develop the information infrastructure to pull these data elements together in a way that produces a true understanding of the community’s health, to make those data available via a browsing tool that helps researchers understand the needs of the community, and to use the resulting knowledge to improve the health of the community. Bakken extended those goals to develop approaches for giving the data and information gleaned from it back to the individuals who had generated the data and to the community at large. Two studies conducted under the WICER umbrella, one dealing with consent and the other with ways of sharing a participant’s tailored research results, are of particular relevance to precision medicine, Bakken said.

Discussing the first of these, she said that the extensive literature on consent shows that members of racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to consent to participate in research for a variety of reasons. WICER’s cohort of 2,271 people was 97 percent Latino, primarily Dominican; was 72 percent female; and had a mean age of 49.6 years. One-third of the cohort had less than an eighth-grade education, and another third had less than a high school education. About 80 percent of the cohort members were immigrants, and most had insurance through Medicare or Medicaid. “When you look at those kinds of socioeconomic factors and expected health literacy level,” Bakken said, “we know these are individuals who typically have been underrepresented in research in general, let alone research that would include collection of genomic information.”

Bilingual community health workers were used to collect the data, and snowball sampling—a non-probability sampling technique in which existing study participants recruit future subjects from among their acquaintances—was used to take advantage of the social networks of the study subjects and of the community health workers. Bakken said that this was an expensive, but critical way to collect data from those not typically represented in research, and that 90 percent of the data were collected in Spanish. The three dependent variables in this study were a willingness to have survey data linked with electronic health record data, a willingness to provide bio-

specimens for long-term storage and use, and a willingness to be contacted for research by investigators outside of the WICER team.

More than 96.3 percent of the WICER cohort consented to link their survey data with their electronic health record data, and 87.5 percent said yes to being contacted by someone outside of the research team. The lowest level of consent, 53.2 percent, was for long-term storage of biospecimens, which Bakken said was better than expected based on formative work that she and her colleagues had conducted in the community. “We were pleased that by working on building trust with the community, involving the community health workers, using snowball sampling, and other steps we were able to get that level of biospecimen participation,” she said.

With regard to specific correlates of consent, Bakken said that having Medicare or Medicaid increased the odds of consent to biospecimen collection but decreased the odds of agreeing to data linkage. Males were less likely to consent to being contacted again for participation in future research. The only variable that was significant to all three types of consent was health literacy, which turned out to be the most important variable when controlling for all the other variables.

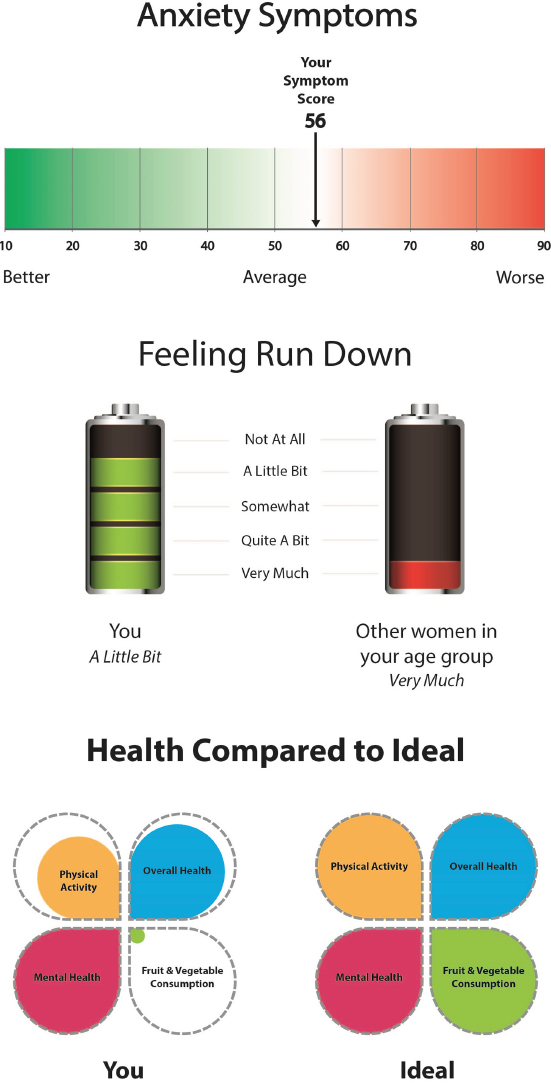

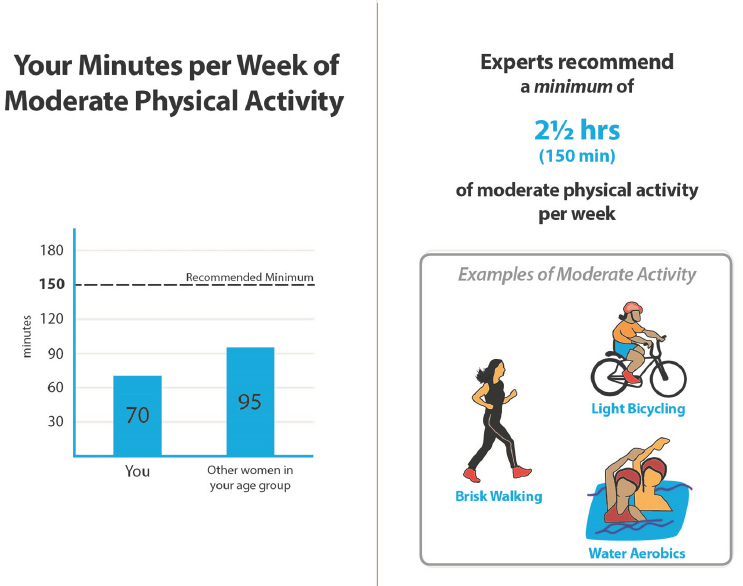

Turning to the second study on information sharing with WICER participants, Bakken said that the approach in that one was to apply some of what she and her colleagues had learned in their work on participatory design of infographics (Arcia et al., 2015, 2016) to genomics and other types of results reporting. She and her colleagues formed 22 focus groups, most of them conducted in Spanish, involving 102 research participants who were shown multiple designs of infographics (see Figure 4-1). One finding was that when working with these populations, giving data in the absence of context is meaningless. “If the visualization did not convey context, the group would create the story that went with the data,” Bakken said. She and her colleagues are currently conducting comprehension testing, which Bakken said should allow the team to create consumer-facing and provider-facing applications.

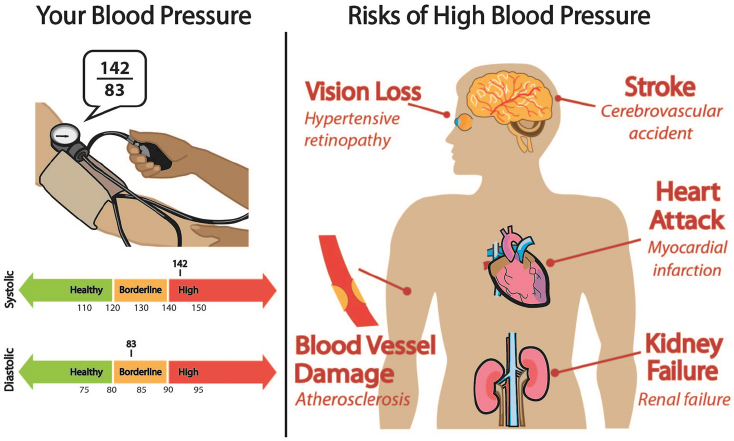

One of the most complex designs for discussing blood pressure (see Figure 4-2) ended up being the preferred design, Bakken said, and feedback from the group revealed that instead of simply being told whether their blood pressure was high or not, the people preferred to receive additional context such as information about the risks associated with hypertension. In presenting the risks, her team used both common language and professional language. “We wanted to make it easy to understand, but we felt it was important that they be able to communicate with their clinicians who might use some of the professional language,” said Bakken, who also showed an infographic that communicated results and actions to take to improve those results (see Figure 4-3).

SOURCES: Bakken slides 13, 14, and 15.

SOURCE: Bakken slide 16.

SOURCE: Bakken slide 17.

NOTE: API = application programming interface.

SOURCES: Bakken slide 18 (Arcia et al., 2015).

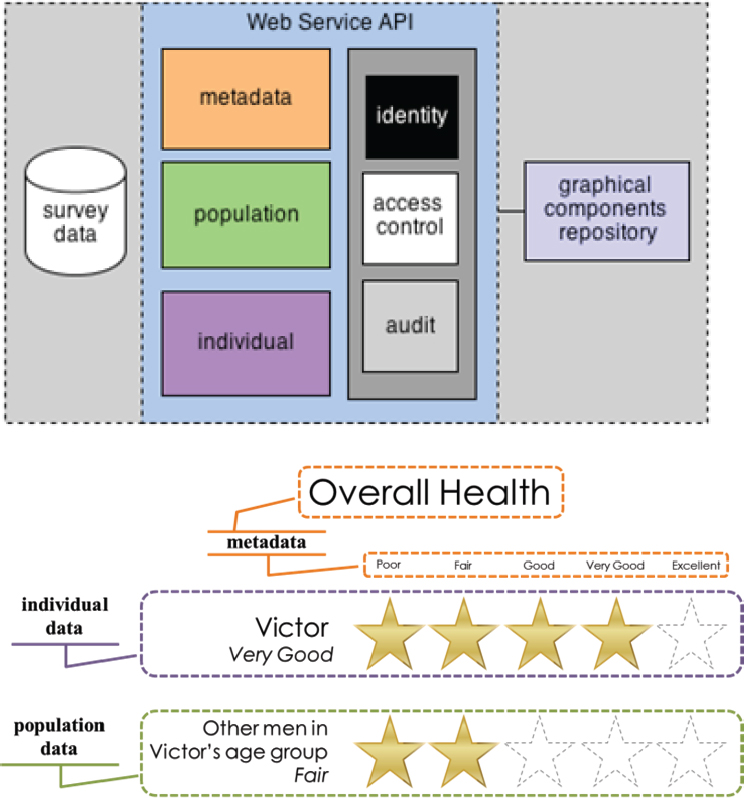

To create these tailored infographics, Bakken’s team developed the EnTICE3 (Electronic Tailored Infographics for Community Engagement, Education, and Empowerment) framework (Arcia et al., 2015) (see Figure 4-4). She and her colleagues have now presented these graphics at six town hall meetings, all of them conducted in Spanish, and have returned the survey data collected in their study to the participants. Participants at the town hall meetings had the opportunity to ask questions and were engaged in discussions of WICER in terms of the PMI Cohort. They were also given the opportunity to provide a biospecimen. As Bakken said she expected,

when the discussions highlighted the importance of the PMI to people who come from the Dominican Republic, those attending the town hall meetings were quite enthusiastic to participate.

In closing, Bakken said that there are multiple aspects of health literacy that affect precision medicine in general and in assembling cohorts in particular. “I think it is vital that we combine health literacy with the principles of engagement with research participants,” she said. Advances in informatics can provide a foundation for tailored approaches, but it will be critical to test messages before introducing them to various target populations. “We cannot just decide what might work,” she said. She also said that her team will soon make the EnTICE3 framework and their infographic designs available as an open-source software package and that she is eager to see how well they can be used or adapted for use in other communities.

ENGAGEMENT AND RETENTION2

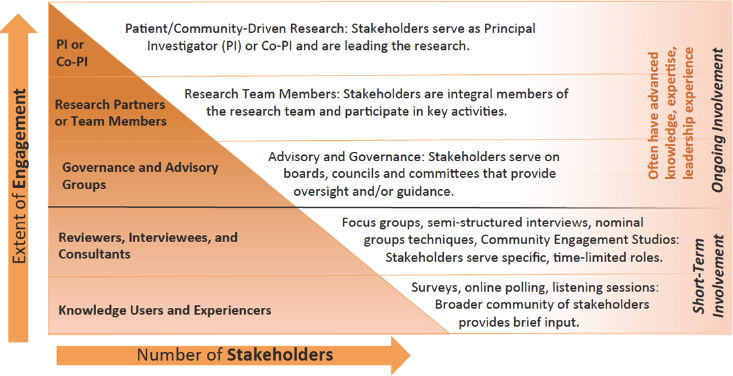

Engagement is bidirectional and has to have an element of co-learning to be successful, Wilkins said; it is not the same thing as outreach, which is unidirectional. There are many different approaches to engagement (Cunningham et al., 2015) (see Figure 4-5), and the best strategy to pursue depends on the type of input and information needed. Some strategies, she explained, are appropriate when the goal is to get participants involved for a limited time, such as in a one-time survey, online polling, semi-structured interviews, or focus groups. Others, where the participants are treated more like equals and require some comfort level to “sit at the table,” are required for a program as large, comprehensive, and long-term as the PMI. This second group of strategies involves community stakeholders in advisory and governance roles, as members of the research team, and in some cases as co-principal investigators.

This multi-tiered strategy has been operationalized in a single project organized by the Mid-South Clinical Data Research Network (CDRN) that involved more than 5,000 people at different levels of engagement; the project was part of a larger effort to recruit three cohorts totaling more than 20,000 individuals for studying obesity, coronary heart disease, and sickle cell disease. Wilkins said that when she proposed engagement at this scale, many had their doubts that it would succeed. In fact, it did succeed and the result, she said, is a system and network that is more likely to engage and involve people over the long term. She added that this engagement

___________________

2 This section is based on the presentation by Consuelo Wilkins, executive director of the Meharry–Vanderbilt Alliance, and an associate professor of medicine Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and Meharry Medical College, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

SOURCES: Wilkins slide 2 (Cunningham et al., 2015).

strategy is likely to be important for retention as well. “If you have not thought about retention when you are designing the program, there is very little chance that you will meet your retention goals at the end,” she said.

One key lesson about engaging stakeholders that emerged from this project is to get them involved early and to engage multiple stakeholders (Wilkins et al., 2013). “You cannot just have one person at the table who is not part of the research team and call that engagement,” Wilkins said. It is also important, she said, to be deliberate in the way that stakeholders are engaged, to take the time to educate stakeholders, to give stakeholders the time to become informed before asking for their input and advice, and to provide feedback to them. It is also important to clearly define roles and expectations, to make the experience bidirectional, and provide opportunities for co-learning, as she had already mentioned.

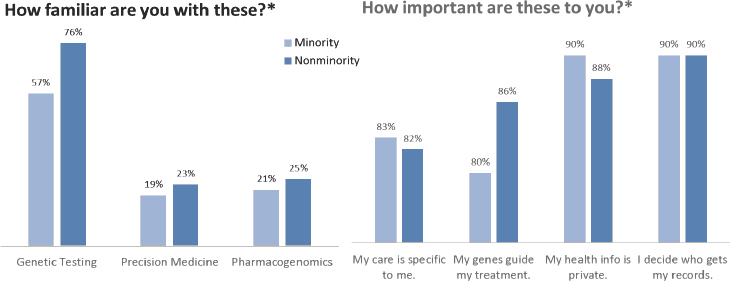

As Wilkins and her colleagues at Vanderbilt began preparing for what was to become the PMI Cohort Program Pilot, they thought it might be important to understand what their patients and community thought or knew about precision medicine and its importance, and to do so they distributed a survey through the Vanderbilt patient portal. Wilkins explained that the demographics of those who responded to the survey were not representative of the Vanderbilt population, but rather of those who most often used the patient portal. Nonetheless, the survey results provided useful information about how little even this well-educated subset of Vanderbilt’s community knew about precision medicine or pharmacogenomics (see Figure 4-6). They also showed that for all races and ethnici-

NOTE: * Scores based on 5-point Likert scale. Participants who chose “Moderately” and “Extremely” were included in the above scores for each category.

SOURCE: Wilkins slide 6.

ties the concepts underlying precision medicine were important, as were privacy concerns.

The survey also posed questions about health literacy, numeracy, and willingness to participate in biomedical research. Caucasians and African Americans had similar levels of health literacy, though there was a bigger difference between these groups when it came to numeracy. Wilkins said she was surprised by the low level of numeracy among this group of well-educated individuals. The survey results also showed that race and levels of health literacy and numeracy all predicted willingness to participate in research, though the numeracy level was the biggest predictor. From these results, Wilkins concluded that it will be important in an era of precision medicine to develop effective methods for communicating risk, probability, and other concepts that depend on numbers rather than just words.

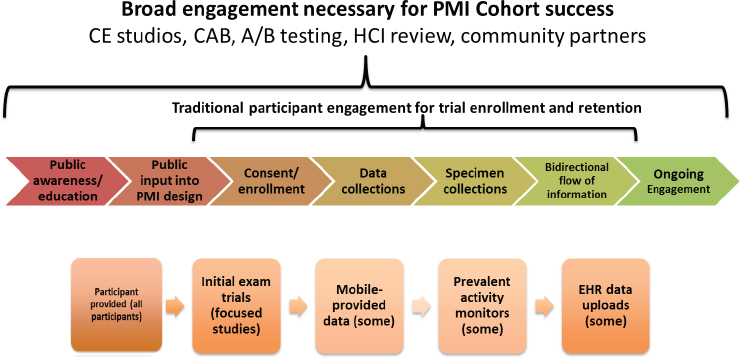

Wilkins then reviewed the engagement plan she will be leading as part of the PMI Cohort Program Pilot (see Figure 4-7). Over the course of 1 year, this initiative will prototype the PMI Cohort Program website, consent form, data tools for collecting basic information, and the participant portal, and it will also pilot several strategies for recruitment and retention as well as advanced data collection tools. To test methods for achieving the broad engagement needed to assemble the PMI Cohort, she and her colleagues will be using a community engagement studio model they developed that allows people to come to the table and provide input on research at any stage or phase of research. She and her colleagues will be doing user testing on a number of different models (Heller et al., 2014; Paskett et al., 2008; Yancey et al., 2006), Wilkins said, and they will then launch them as pilots to get broader review.

NOTE: CAB = community advisory board; HCI = human computer interaction; PMI = Precision Medicine Initiative.

SOURCE: Wilkins slide 8.

In the first week after the PMI Cohort Program was announced, Wilkins said, she and her colleagues had already identified 17 priority populations they will need to engage in the PMI Cohort Pilot Program. The presumption, she said, is there will be people who are knowledgeable about precision medicine—some of whom have family histories of genetic conditions and others who are just interested—and who will immediately want to participate. There will be other groups of people, however, who have no knowledge of precision medicine, who have never participated in research, or who are concerned, distrusting, and weary of the process in general. “We will have to have boots-on-the-ground approaches to engaging them,” said Wilkins, who added that of those 17 priority populations, several are composed of racial and ethnic minorities and one consists of people with limited health literacy. She emphasized that members of each of these 17 priority populations will be seated at the table and will provide input on the content and strategies and participate in user testing.

From the early work they have done on prototyping the portal and on methods of delivering data back to the participants, it is clear that those who have lower health literacy are not able to understand all of the great deal of information they are presented with. Wilkins said it will be critically important to find a way to return value to all of the participants if the goal is to retain them in this research over the long term. “What is valuable to someone with a genetic condition in their family is not going to be relevant

to most people, especially those who have limited health literacy,” Wilkins said. “Thinking about how to address those differences and provide something of value to those with low health literacy so they remain engaged in the work will be important.”

Wilkins concluded her remarks by noting that engaging populations of interest will require tailoring various approaches to meet the needs of those specific groups. “When we are thinking about this large group of 1 million people, we need many strategies for engaging individuals,” she said. With regard to retention, she said the key will be to build relationships and trust, and for some of these populations, especially those that have been marginalized and disenfranchised from the research community, building relationships and trust will take time and additional resources.

MAKING DECISIONS ABOUT REPORTING RESULTS3

One issue with returning the results of gene sequencing to individuals who participate in the PMI Cohort—and eventually to all patients—is that a whole-genome sequence has the potential to yield secondary findings about a participant’s genetic makeup that may have profound implications, Appelbaum said. Studies of participants’ preferences, he noted, have found consistent interest in knowing about these secondary findings, particularly if they are clinically actionable. In addition, a growing number of federal agencies and expert panels have recommended that at least some secondary findings from genome sequencing be made available to participants. The logic of returning these results to participants is that those data may include information that is medically actionable or, if not medically actionable, is personally actionable, perhaps in how someone structures his or her life or finances. The carrier status of a recessive condition could have reproductive implications, and pharmacogenomic information could have implications for current or future drug responses. Given these possibilities, Appelbaum said, the challenge is to engage with patients in a way that helps them make meaningful decisions about the information they want or do not want to receive.

Several years ago, Appelbaum and his colleagues surveyed genetics researchers who had presented their research at the American Society of Human Genetics meeting or who had grants focused on genome sequencing (Klitzman et al., 2013). As part of the survey, they asked 234 genomic investigators what information they thought should be shared with partici-

___________________

3 This section is based on the presentation by Paul Appelbaum, the Elizabeth K. Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law and the director of the division of law, ethics, and psychiatry at Columbia University, and the statements have not been endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

pants during the informed consent process before the participants made a decision about the return of secondary findings. The researchers also asked what benefits (see Table 4-1) and risks (see Table 4-2) should be disclosed. The survey found, Appelbaum said, that more than half of the researchers, and in many cases more than three-quarters of the researchers, endorsed returning all of this information to research participants.

Appelbaum and his colleagues then asked the researchers what else should be disclosed, and many researchers endorsed returning information that might have implications for the participants’ relatives or that might affect family relationships. Nearly all the researchers mentioned the potential importance of participants sharing information with family members, and some two-thirds of the researchers thought it was important to talk with the participants about how secondary findings with implications for relatives would be handled if the participants became incompetent or died. Other topics the researchers thought should be addressed with participants included the possibility that subsequent studies on banked biospecimens could return secondary findings later in life, data security procedures, and

TABLE 4-1 Benefits That Should Be Disclosed from Secondary Findings of Genome Sequencing

| Researchers (n = 241) | Participants (n = 20) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits | % | Count | % | Count |

| A treatable disorder might be identified | 94.5 | 225 | 95 | 19 |

| Prophylactic measures may be available to prevent some disorders | 84 | 200 | 95 | 19 |

| Modern reproductive techniques (e.g., preimplantation genetic diagnosis) may allow carriers to have children with minimal risk of specific disorder | 63.4 | 151 | 85 | 17 |

| Knowing pharmacogenetic status can increase the likelihood of efficacy of some medications and reduce the change of adverse reactions | 67.6 | 161 | 90 | 18 |

| Knowing one’s propensity for developing particular condition can help with life planning | 57.6 | 137 | ||

| Knowing whether they carry a disease mutation can relieve anxiety for some people | 85 | 17 | ||

SOURCES: Appelbaum slide 5 (Klitzman et al., 2013).

TABLE 4-2 Risks That Should Be Disclosed from Secondary Findings of Genome Sequencing

| Researchers (n = 241) | Participants (n = 20) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risks | % | Count | % | Count |

| The risk of false-positive findings | 94.5 | 225 | ||

| The risk of false-negative findings | 85.7 | 204 | ||

| The findings may be wrong | 90 | 18 | ||

| Possible negative psychological responses | 82.8 | 197 | 90 | 18 |

| The danger of falsely concluding from a negative result that they are not susceptible to a result, e.g., because of limitations of the testing and existing knowledge | 78.6 | 187 | 90 | 18 |

| Possible confusion resulting from the ambiguity of the results | 76.1 | 181 | 80 | 16 |

| The possibility that the interpretation of the findings might be different in the future as more knowledge is acquired | 85.7 | 204 | 90 | 18 |

| The risk of stigma/discrimination (e.g., in insurance) if information about their test results becomes known | 71.8 | 171 | 90 | 18 |

| Possible need for further testing, counseling and follow-up, and the unavailability of fund from the study to pay for it | 84.9 | 202 | 85 | 17 |

| Risks to data security and confidentiality | 53.4 | 127 | 85 | 17 |

SOURCES: Appelbaum slide 6 (Klitzman et al., 2013).

the penalties for researchers failing to protect or possibly use a participant’s genomic information. Other issues that researchers suggested should be flagged for participants were possible paternity-related findings or findings of incest and also whether the participant’s choices could be overridden in certain circumstances, particularly when those secondary findings turn out to be actionable. More than three-quarters of the researchers believed that participants should give consent at the time of initial participation for potential contact at some future date and also should consent to placing secondary findings into the participant’s electronic health record.

Taken together, these information choices represent a great deal of information that must be conveyed to participants, particularly in the context of getting consent to participate in a study in the first place. When asked about how much time they would be able to spend on this topic, the researchers said they believed they could allocate only 15 to 30 minutes

for this portion of the consent process, which Appelbaum said creates a dilemma. “Cramming all of that information into 15 to 30 minutes is either not possible, or the information may be given so quickly that the likelihood that someone would understand would be about nil,” he said.

The solution to this dilemma is to develop new approaches to getting consent, Appelbaum said, and based on the survey responses, interviews, and a literature review, he and his colleagues identified four potential models to consider (Appelbaum et al., 2014). The first was the traditional model of getting consent upfront: participants are given all of the information at once while consenting to participation in the underlying research, they sign a consent form, and the process is over. The advantages of this model are that it resembles the traditional consent process familiar to the research community, the participant receives all of the information about potential secondary findings prior to deciding whether to participate, and the participant can choose which the types of secondary findings to receive or whether to opt out of receiving these findings. The potential disadvantages of this model are that it adds time and information to an already lengthy and complex process and the participants’ preferences may change after the initial consent.

The second model uses a staged consent process, in which there is a brief mention at the time of initial consent of the potential for secondary findings and the potential for recontact, and there is a second, more detailed consent process if reportable results are found. The advantages of this model are that it reduces the time spent discussing secondary findings during the initial consent for the large number of people who are not going to have secondary findings, and it allows more detailed and specific information to be provided later to those who do. This model also allows the participant to make decisions about secondary findings closer to the time that they can receive those findings—thus allowing them to take their current circumstances into account when making the decision—and it also allows them to maintain choice about which types of secondary findings to receive or whether to opt out altogether. The potential disadvantages include the costly and burdensome need to follow up with participants and the potential that recontacting a participant may reveal unwanted information about a secondary finding and negatively affect the participant. “Think about how well you would sleep after a discussion in which you were told there may be information you may or may not want to know,” Appelbaum said. Finally, the participant’s decision to enroll in the underlying research project would be made without full information about the potential return of secondary findings.

The third model, mentioned by some of the researchers, was the mandatory return, one-size-fits-all model. In this model, which is based on the original American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics recom-

mendations on secondary findings in clinical genomic testing (Green et al., 2013), participants consent to the return of specific categories of secondary findings at the time and as a condition of enrollment. The advantage of this approach is that it simplifies consent at enrollment—the participant receives information only about selected secondary findings and does not have to choose which findings to receive. This model also clearly defines the researchers’ obligations to return predetermined secondary findings, and the participant maintains a degree of choice about whether to participate in the study. The potential disadvantages include restricting the participant’s choices—they cannot choose which findings to receive and cannot refuse to accept the designated findings—and this lack of participant choice could become a disincentive to enrolling in genomic research. In addition, efforts to recontact participants could be costly and burdensome for researchers.

The fourth model, which Appelbaum said was one he and his colleagues had not thought of until it was suggested by some of the survey respondents, is the outsourcing model, in which participants are referred to third parties for both consent and the return of secondary findings. Arguably, Appelbaum said, this model works better in a research setting than in a clinical setting, but it takes the responsibility of explaining and conveying clinical findings out of the hands of researchers and presumably puts it in the hands of clinical experts. The advantages of this model to the researchers are clear in that it allows them to avoid the entire issue and only leaves them with the obligation of returning each participant’s raw data. The potential disadvantages of this model are that the participants may not become aware of medically significant data within the raw data and that services for genomic interpretation and counseling are not widely available today. In addition, this approach could exacerbate health disparities because further interpretive services may be costly and thus limited to wealthy participants.

With the four models in hand, Appelbaum and his colleagues went back to the original pool of researchers to ask for their views about the models given two situations, one in which there were no resource constraints, and the other with real-world resource constraints (Appelbaum et al., 2015). The researchers were also asked to rate the characteristics of the various models. The results, Appelbaum said, were somewhat surprising (see Table 4-3). In the no-constraints situation, the researchers were split between traditional consent and staged consent, with little support for the outsourced model, even though that would be the least burdensome for researchers, and almost no support for the mandatory return model.

In the real-world situation, almost half of the researchers chose the traditional consent model, while far fewer favored the staged consent model because of the time and effort needed to recontact participants each time

TABLE 4-3 Researchers’ Favored Models of Consent

| No Resource Constraints | Real-World Constraint |

|---|---|

| Traditional consent (32.3%) | Traditional consent (47.8%) |

| Staged consent (32.3%) | Outsourced consent (18.7%) |

| Outsourced consent (13.1%) | Staged consent (13.1%) |

| Mandatory return (8.6%) | Mandatory return (6.6%) |

SOURCE: Appelbaum slide 18.

results became available. Outsourcing had somewhat higher levels of support, but again, few researchers liked the mandatory return model.

When the models’ attributes were rated, traditional consent was rated first in every category except in terms of the burden it places on researchers. “This was a big surprise to us,” Appelbaum said, “but it may be that people like doing what they have always been doing and are comfortable with.” From these results, Appelbaum concluded that there was no consensus concerning which consent model was optimal and also that there is a great deal of concern about the resources needed to stage consent.

Appelbaum concluded his presentation by noting that many whole-genome sequencing studies will generate some number of secondary findings of clinical or personal significance and that there is a rough consensus among researchers that at least some of these secondary findings should be offered to research participants. The complexity of obtaining informed consent will push the field away from the traditional model, he predicted, but which model becomes dominant—perhaps a hybrid of two or more of these models or one yet to be developed—will depend on a mix of practical concerns and normative considerations.

REACTIONS TO THE PRESENTATIONS4

Marin Allen first commented that variation and continuity are important concepts for health literacy, just as they are for genetic literacy, which

___________________

4 This section is based on the comments by Marin Allen, deputy associate director for communication and public liaison and director of the Public Information Office at NIH, and Benjamin Solomon, chief of the division of medical genomics at Inova Translational Medicine Institute, and the statements are not endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Joseph McInerney had stressed in his presentation. She then pointed to Bakken’s idea that, in an important change to the business-as-usual approach, health literacy needs to be considered at the earliest stages of the recruitment process, not measured later once the research has begun. The notion of comparing an individual’s results to those of neighbors was an interesting idea, she said, but she wondered if also adding a comparison to “perfect circumstances” to the graphics Bakken presented might be worth testing. She also commended Bakken for her team’s strong emphasis on cultural respect in its approach to her studies and for how thorough the team was when thinking about subpopulations.

With regard to Wilkins’s presentation, Allen said the notion of bi-directionality is also one of continuous feedback and that two-way communication between the researcher and participant should be continuous rather than in stages. Allen thought that Wilkins’s recognition of what often happens when there is a single representative of the community on advisory boards is important in the health literacy environment. In that setting, individuals can be intimidated, and furthermore, they do not really represent the community and instead represent their own needs or aspirations. She also said that she thought the patient portal as a proxy for the interested community member was an important concept that offered the potential to understand that particular population.

Turning to Appelbaum’s presentation, she said she thought that the emphasis in the four models he presented was what she called “CYR, or cover your researcher,” in that they all are legally and ethically defend-able but do not address the topics that researchers are frightened of telling people. She said that yet another model is necessary, one that incorporates health literacy and frames these difficult conversations to make them more useful for more people more of the time.

To put his comments into context, Benjamin Solomon first described the precision medicine work his organization has been doing for the past 5 years. He and his colleagues have done whole-genome sequencing on nearly 10,000 people in 3,000 families and have been monitoring the health of these individuals. From that perspective, he said, his view is that the research community at large has generated both a great deal of excitement around genomics and precision medicine and a great deal of hype. While it was exciting to see President Obama standing next to the double helix at a State of the Union address, he said, he worries that patients and research participants expect a great deal from taking part in the PMI without realizing how early it is with regard to what can be learned from genomics and the tremendous variability in the human genome.

One important point that Solomon said he took from the three presentations was the need for flexibility and the ability to change models as the field learns. This will be a challenge, he acknowledged, for fields that are

used to traditional research models with checks and balances and logistics. Just as Appelbaum described the need for a different model of consent, Solomon said the research community needs to have different models for how it conducts its studies as the precision medicine field grows with the new knowledge and experiences that will come from carrying out these research projects.

Another message that Solomon said all three presentations alluded to was that it is going to be tremendously expensive in terms of time and personnel to get participants enrolled, engaged, consented, and informed. One point that he said he wishes the public understood was that the people they will interact with in this project are just a small percentage of the total personnel involved and that there are many people working behind the scenes on data analysis, data security, and other critical aspects of this type of endeavor.

Finally Solomon brought up what he said he suspected might be a controversial topic—the idea that this effort should extend to children and not just adults. “If we are doing precision medicine and want to learn what affects a person’s health and well-being, it is challenging if we start in the adult realm,” Solomon said. “I know doing this type of research in pediatrics raises bioethical concerns, but I worry we are going to lose the opportunity to learn from children and to learn how disease and health really progress if we do not start early in the lifespan.”

Laurie Myers remarked on how hard these concepts are to communicate to patients, but she said that she is optimistic after hearing the three presentations that it will be possible. In Bakken’s presentation, she said, she heard that it is possible to engage in a culturally respectful manner participant groups that have been historically underrepresented. Wilkins pointed to the importance of two-way engagement as being more than just an afterthought and of involving participants in many ways throughout a research project. From Appelbaum’s presentation, Myers said, she got the message that the field still needs to figure out the best way to get informed consent from research participants—to help them understand the important points and not just overwhelm them with information. Allen reiterated the notion of continuous feedback and cultural respect, and Solomon highlighted the difficulty of communicating to patients what precision medicine can do for them when the field is still very much in its infancy.

DISCUSSION

Cindy Brach began the discussion with an idea for a different model of consent that is derived from the new division-of-labor, team-based models being implemented in primary care practices. In this model, participants might first watch a video at their own pace and then have a chance to ask

questions to the person charged with obtaining informed consent from participants. Brach reiterated the importance of developing and testing communication tools at the beginning of the research process and noted how impressed she was with the graphics that Bakken’s team had developed using this approach. Brach also noted the point that McInerney had made about learning lessons from the genetic counseling field. She added that she found the staged model of consent troubling on ethical grounds.

Appelbaum said he believes that this project could embrace the idea of subject educators or even participant educators in an aggressive manner and, by doing so, provide an example of a new approach to consent that could extend into the clinical realm as well as the research realm. In his opinion, he said, the problem with doctors and researchers trying to obtain consent from a patient or participant is that these experts no longer know what the non-expert does not know. He said he believes that some combination of technology with dedicated educators and participants who are trained to teach rather than obtain consent could provide a better approach to consent. He noted that a colleague of his at Columbia is leading an effort to develop 3- to 5-minute videos covering discrete topics related to genomic research, including secondary findings.

Bernard Rosof asked Bakken to list some lessons she had learned that might allow other communities to accomplish what she and her colleagues have done in the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The most important lesson, Bakken said, is to get the community participating from the beginning, which in the case of her work meant going into the community and developing an understanding of what the community members thought was most important in terms of the information they wanted to receive back from the research. Community participation continued throughout the process of her team prototyping infographic designs. Another lesson, she said, was the need to iterate to make sure that the designs would work in specific cultural contexts. She said that cultural context proved to be more important than health literacy level in the community she was studying and that more information made the infographics more meaningful, which in turn led to increased understanding.

Betsy Humphreys from the National Library of Medicine (NLM) said she hoped that the type of research discussed at the workshop would provide feedback to improve the genetic reference and gene information tools that NLM develops in collaboration with other NIH institutes. In fact, she said, she is optimistic that the PMI Cohort will be a good base for research on issues of health literacy, consent, and communicating genomic information to populations of different socioeconomic, educational, cultural, and ethnic backgrounds. With regard to returning information to study participants or to the public, Humphreys said that there will be a group of participants whose primary motivation will be getting back every piece

of information generated, and as a result the consent process will have to include alerting participants that they may receive information that will not be well explained.

Humphreys also wondered if anyone had thought about recruiting families into the PMI Cohort and the possibility that as the study proceeds, those enrolled as children will rebel against being in the study when they become teenagers. Myers added that teenagers are becoming aware of genomics and genetic testing thanks to the popular media, and she cited an episode of the reality show The Kardashians that she watched with her 16-year-old daughter in which the grandmother had breast cancer, the family was being tested for BRCA mutations, and one of the sisters resisted because she did not want to know if she had one of the deleterious mutations.

Wilkins said that parent–child dyads are a priority population and that representatives of that population are involved in discussions about what it means to be involved in the PMI Cohort. “This is a different discussion if the child is an adolescent versus a toddler,” she said. She also agreed that the PMI provides a unique opportunity to study health literacy and communication, given the PMI’s emphasis on giving results back to the participants. “How do we do that in a meaningful way, especially with so many different subpopulations, expectations, literacy levels, and educational attainment?” she asked. In her study, she said, a team member from Vanderbilt’s Effective Health Communications Core helps put in place mechanisms not only to design effective methods for recruiting participants but also to help understand how member of the different populations will respond to information and what will be needed to retain them in the study over the long term. “I would say we are preparing for the very broad range of information that people will want to get back,” Wilkins said. “We want to have a system in place that allows us to respond to the needs, values, and preferences of everybody who is involved.”

Jennifer Dillaha from the Arkansas Department of Health commented that she sees a quality consent process as a systems property, not a property based on individual behaviors or on the characteristics of the people in the system. In thinking of relationships with the community as a systems property, the challenge becomes establishing the PMI so that it sustains the quality of relationships and communication regardless of whether certain visionary individuals stay with the initiative. “How do we make this a property of the work we are doing and not one that depends on certain individuals doing what they think is the right thing?” Dillaha asked.

Wilkins agreed strongly that there has to be a process in place for sustainability, particularly for the public awareness, education, and genomic literacy pieces. The approach that her team is taking is to identify local and national community organizations, rather than individuals, as partners. Her

hope is that if the project goes beyond the pilot phase, a national coordinating center will work to maintain these partnerships over the long term. One idea is to have PMI ambassadors around the country representing both geographic and demographic communities; these ambassadors could come from advocacy organizations that are already established in the different communities, Wilkins said. She expressed her surprise at how much people in various organizations already know about the PMI, though she said President Obama’s public support for the PMI is likely the reason for the increased public awareness. “I think that does open some doors that can create some sustainability,” she said.

Wilma Alvarado-Little noted that one of the infographics Bakken showed (see Figure 4-1) included mental health status, and she wondered how mental health–related findings might be returned to participants, given that mental health is not a subject for discussion in some cultures. Bakken responded that the importance of including mental health items came from community-based organizations and community members on the design team who felt that stress, in particular, was not adequately represented. As a result, questions related to different types of stress were added to the survey, though the only stress that was significant turned out to be financial stress. However, the team included a safety plan that would trigger an intervention for anything alarming related to mental health or to blood pressure.

Earnestine Willis, who heads a community-based participatory research (CBPR) project, commented on the importance of recognizing available assets in the community when conducting this type of complex research program, and she asked Wilkins if her team had some mechanism in place to ensure that the PMI Cohort pilot has a shared vision with the involved communities. In particular, she was concerned that the PMI does not clearly embrace the complementary role that participants need to share with researchers. Wilkins responded that the PMI is not a CBPR project and that, based on her experience, training, and prior involvement in community-engaged research, she believes the PMI’s framework does not lend itself to CBPR. “There are many pieces that are predetermined,” she said. “It is disease agnostic from the beginning. It is a cohort that is being established with no health condition identified a priori, and it is a group of people who will serve as a database for future research. As such, I think it would be challenging to make it into a CBPR,” Wilkins said. In fact, she said, from her perspective as a community-engaged researcher, the PMI Cohort may be more engaged than any prior project conducted by the genetics and genomics community, but she would not call it partnered.

Wilkins then explained that her institution, in partnership with the University of Miami, was about to launch a center of excellence for precision medicine and population health that will focus on African Americans and Latinos. The planning process for this center included community members

from both Nashville and Miami who provided input into the design of the center and its health priorities, as well as on their concerns about privacy and trust. “I am not sure I would call that a CBPR either because it is about infrastructure, but I think it is more engaged and responsive to the needs of the community,” Wilkins said.

To Michael Villaire from the Institute for Healthcare Advancement one troubling aspect of precision medicine is that it will ultimately place a burden on individuals to contextualize challenging information and use it to make difficult decisions. Given that situation, he wondered if the consent process might have an option of asking participants if they were interested in having another, trusted person present when they receive information to help them make sense of it and make appropriate decisions. Appelbaum said that there will be options for people to share the information they receive and the ways in which they receive that information and that good clinicians and researchers have always been open to bringing somebody with them to help interpret and work through information. He then added that there is work in progress testing the utility of an online consent process with hyperlinks that would enable a participant to get more information on specific topics, if desired, with a simple mouse click. A video library could be used in the same way, he added. He said that his colleagues are starting a study in which they will ask people whether they are more comfortable receiving information online or face-to-face and then look at the outcomes in terms of information assimilation. “There is a great deal of opportunity for individualizing the consent process,” he said.