Appendix A

Public–Private Partnerships for the Sustainable Development Goals

A Review Document Commissioned by the Forum on Public–Private Partnerships for Global Health and Safety of the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, August 2016

Prepared by Christian Acemah, Executive Secretary and Special Advisor to the UNAS Council, Uganda National Academy of Sciences (UNAS)

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

| AAAA | Addis Ababa Action Agenda |

| ACSC | African Civil Society Circle |

| AfDB | African Development Bank |

| AU | African Union |

| BOOT | build, own, operate, transfer |

| CARAC | Corporate Accountability and Risk Assurance Committee |

| CSO | civil society organization |

| CSR | corporate social responsibility |

| DNDi | Drugs for Neglected Disease initiative |

| EAC | East Africa community |

| ECA | Economic Commission for Africa |

| ECOWAS | Economic Community of West African States |

| FDI | foreign direct investment |

| FFD3 | Third International Conference on Financing for Development |

| ICSU | International Council for Science |

| ICT | information and communications technology |

| IEG | independent evaluation group |

| IFC | International Finance Corporation |

| LMIC | low- and medium-income country |

| MCC | Millennium Challenge Corporation |

| MDG | Millennium Development Goal |

| MoI | means of implementation |

| NCD | noncommunicable disease |

| NEPAD | New Partnership for Africa’s Development |

| NGO | nongovernmental organization |

| OAU | Organization of African Unity |

| ODA | official development assistance |

| PIDA | Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa |

| PPP | public–private partnership |

| REC | regional economic community |

| SADC | Southern African Development Community |

| SAM | Sustainability Assessment Matrix |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| UHC | universal health coverage |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| UNSC | United Nations Statistical Commission |

| VfM | value for money |

List of the Sustainable Development Goals

| SDG 1: No Poverty | End poverty in all its forms everywhere. |

| SDG 2: Zero Hunger | End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture. |

| SDG 3: Good Health and Well-Being | Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. |

| SDG 4: Quality Education | Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all. |

| SDG 5: Gender Equality | Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. |

| SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation | Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. |

| SDG 7: Affordable and Clean Energy | Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable, and modern energy for all. |

| SDG 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth | Promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth; full and productive employment; and decent work for all. |

| SDG 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure | Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation. |

| SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities | Reduce inequality within and among countries. |

| SDG 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities | Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. |

| SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production | Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns. |

| SDG 13: Climate Action | Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts. |

| SDG 14: Life Below Water | Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development. |

| SDG 15: Life on Land | Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems; sustainably manage forests; combat desertification; halt and reverse land degradation; and halt biodiversity loss. |

| SDG 16: Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions | Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development; provide access to justice for all; and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels. |

| SDG 17: Partnerships for the Goals | Strengthen the means of implementation, and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development. |

THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS

On September 25, 2015, more than 150 world leaders gathered at the United Nations headquarters in New York to formally endorse a new global agenda for the next 15 years. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which includes the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), is the result of an exhaustive consultation process that lasted more than 2 years. The agenda lays out an inspirational vision of the future, in which poverty and hunger are eliminated, gender equity and quality education are achieved, and the effects of climate change are contained. Speaking in New York, Helen Clark, administrator of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and former prime minister of New Zealand, said, “Ours is the last generation which can head off the worst effects of climate change and the first generation with the wealth and knowledge to eradicate poverty” (UNDP, 2015).

The roots of the SDGs extend back to the turn of the millennium, when world leaders also met in New York and approved the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The MDGs concluded in 2015, and the new SDGs are a natural evolution of the same idea. But the SDGs go much further. They expand the scope of the development agenda to include goals on economic growth, climate change, sustainable consumption, innovation, and the importance of peace and justice for all (UNDP, 2015). They also shift the focus from just low- and middle-income countries to the whole world. Although like the MDGs the main thrust of the new goals is poverty alleviation, there are many specific goals with relevance to high-income countries. In short, the SDGs are the first universally agreed-upon secular plan for the future of the planet and all people. At

their core, however, both the MDGs and the SDGs are the same: a belief that humanity—with sufficient determination and investment—has the ability to achieve sustainable development. That is, development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (ECA, 2015a).1

Indeed, 15 years of the MDGs have recorded significant and unprecedented achievements toward this vision. In 2010, 5 years before the deadline, the world met the first goal of cutting extreme poverty in half.2 This statistic is somewhat skewed by the rapid economic development that was already under way in China long before world leaders adopted the MDGs. However, the MDG framework likely did have a powerful effect on global poverty. Even when China is excluded from the data, the world’s share of impoverished people still fell from 37 percent in 1990 to 25 percent in 2008 (McArthur, 2013). Globally, the MDGs have also recorded significant achievements in increasing primary school enrolment and health outcomes. The primary school net enrollment rate in developing regions reached 91 percent in 2015, up from 83 percent in 2000; the under-5 mortality rate declined by more than half, dropping from 90 to 43 deaths per 1,000 live births between 1990 and 2015. The malaria incidence rate fell by an estimated 37 percent and the mortality rate by 58 percent (UN, 2015). These achievements seem to justify Bill Gates’ 2008 address to the UN General Assembly, where he called the MDGs, “the best idea for focusing the world on fighting global poverty that I have ever seen” (McArthur, 2013).

These benefits, however, have not been evenly distributed across the globe; a more granular approach to the data finds striking geographical inconsistencies. Within Africa, there are differences in progress made on the MDGs between regions. Countries in East, West, and Southern Africa have in general made better progress than those in Central Africa (English et al., 2015). All together, South and sub-Saharan Africa succeeded in reducing poverty rates by 14 percent, from 56.5 percent in 1990 to 48.4 percent in 2010. Although significant, this decrease falls well below the MDGs established target of a 28.25 percent reduction for the region. Five years later, at the conclusion of the MDGs, overall poverty rates still frustratingly hovered around 48 percent (ECA, 2015a). Certain countries

___________________

1 This definition of sustainable development is taken from Our Common Future (see http://www.un-documents.net/our-common-future.pdf [accessed August 15, 2017]), also commonly known as the Brundtland Report after the chairperson of its authoring commission, Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland. Released in 1987, the Brundtland Report contains what is now the most widely recognized definition of sustainable development (ECA, 2015a).

2 Defined by the international benchmark of those living on less than $1.25 per day (UN, n.d.).

did record higher levels of success on this goal, led by the Gambia with a 32 percent reduction, and followed by Burkina Faso, Niger, Swaziland, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Malawi (ECA, 2015b). On the environmental front, Cabo Verde succeeded in increasing its forest cover by more than six percentage points, with millions of trees planted in recent years (ECA, 2015b).

Most African countries have shown steady progress in expanding access to basic education. In 2012, Algeria, Benin, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, Congo, Mauritius, Rwanda, South Africa, Tunisia, and Zambia all recorded a net enrollment rate of more than 90 percent. However, across the continent, one-third of pupils who start grade one today will likely not reach the last grade of primary education. With a 67 percent primary completion rate, Africa is still far from achieving the goal of primary school completion for all (MDG 2) (ECA, 2015b). Africa also remains the region of the world with the highest maternal mortality rate, despite significant progress. Only Cabo Verde, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, and Rwanda have reduced their maternal mortality ratio by more than 75 percent between 1990 and 2013 to meet MDG 5 (improve maternal health) (ECA, 2015b).3 Across Africa, the MDG areas that remain unfulfilled include income poverty, hunger and malnutrition, maternal and child health, gender inequality, inadequate access to antiretroviral drugs, and the MDG 8 targets, in particular those addressing international trade and financial systems that continue to be unfair and unstable (Akelyira, 2013).

In short, although the international community has lauded the MDGs as a success, results in Africa are mixed. The reformulation of the global agenda into the SDGs opens a space to reflect on these successes and shortcomings, and to refocus development efforts for the next 15 years. Like the MDGs, the SDGs offer an opportunity to unify, galvanize, and expand efforts to improve the lives of the world’s poorest people (McArthur, 2013). But this focused effort will not happen automatically; it requires the conscious commitment of individuals working in every sector—government, civil society, and private enterprise.

FOCUS ON AFRICA

A critique leveled at the original MDGs by many academics and organizations is that the process and the goals were fundamentally donor led (Melamed and Scott, 2011). As such, the goals have been accused of penalizing the poorest countries, where initial conditions made achieving

___________________

3 For further discussion on Africa’s successes and failures in pursuing the MDGs, see the Economic Commission for Africa’s assessment report here: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/mdg/mdg-reports/africa-collection.html (accessed April 20, 2017).

them more difficult (Easterly, 2009). Additionally, skeptics have pointed out that the MDGs paid little attention to locally defined and owned definitions of development and progress (Sumner, 2009). Mindful of these criticisms, African leaders, organizations, and negotiators have begun to develop a clear African position ahead of important international events (Ramsamy et al., 2014). This participatory process, now internationally recognized as the common African position (CAP), brings together stakeholders at the national, regional, and continental levels among the public and private sectors, parliamentarians, civil society organizations (CSOs)—including women and youth associations—and academia, in consultation to reach consensus on how to address the important challenges facing the continent.

African stakeholders have elaborated the CAP on topics ranging from the world drug problem, to the UN review of peace operations, to the post-2015 development agenda. Beginning at the Busan High-Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness in 2011 and continuing into the formulation of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs, African countries have pushed forcefully for their interests with remarkable success (Ramsamy et al., 2014). The Third International Conference on Financing for Development (FFD3), a conference to determine the magnitude and sources required to finance the post-2015 development agenda, was a resounding success for African negotiators (Lawan, 2015). The Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA), adopted at the FFD3, makes specific mention of Agenda 2063 and the New Partnership for Africa’s Development—policy instruments owned and led by Africa—as essential components of a successful post-2015 development agenda (AAAA, 2015).

The success of the CAP is further visible in the harmony between the SDGs and Agenda 2063, the African Union’s (AU’s) overarching vision for the continent. Agenda 2063 is not a planning document, but rather it is made up of seven aspirations that outline, “the Africa you would like to have 100 years after the founding of the OAU [Organization of African Unity],” the continental body that morphed into the AU in 2002 (Ighobor, 2015). First among the AU’s aspirations is, “a prosperous Africa based on inclusive growth and sustainable development,” in particular a 7 percent growth rate—the same as SDG 8 (Ighobor, 2015). To outline the mutual support and coherence of Agenda 2063 and the SDGs, the AU has already created a table expressing the linkages between the two agendas (AU, 2015). If anything, Agenda 2063 is in most cases more specific on the targets to be achieved. Under-Secretary-General and Special Adviser on Africa Maged Abdelaziz, in an interview with Africa Renewal, said,

In education, for instance, the SDGs talk about achieving universal primary and secondary education, while Africa’s Agenda 2063, in addition

to targets on primary and secondary education, sets a specific target of increase in tertiary education. Water security is another example. The SDGs call for a substantial increase, but Agenda 2063 calls for a specific increase. The same goes for other targets, including ICT. (Kuwonu, 2015)

There are, however, some aspirations of Agenda 2063 that do not have clear parallels in the SDGs, such as the goal of a politically united Africa, the establishment of continental financial and monetary institutions, and the pursuit of an African cultural renaissance (AU, 2015). Additionally, some SDGs do not approach solutions from an African perspective. The agriculture sector, for example, is still mostly treated through the lens of hunger and malnutrition, rather than through agri-business and job opportunities for the youth (Lawan, 2015).

Nevertheless, to a large degree, African countries, speaking with one voice, managed to incorporate their vision and programs into the 2030 Agenda such that the SDGs are now in line with Africa’s strategic thrust. The SDGs are in many ways an opportunity for Africa to now take advantage of international attention, expertise, and financing to pursue an agenda that it has already set for itself.

Why Partnerships Matter for the SDGs

Although an oft-overlooked fact, domestic government revenue was actually responsible for 77 percent of spending toward the MDGs. In general, this domestic financing has been more stable, aligned with government priorities, predictable, recurring, and easier to implement than donor funding (GSW, 2015). Ideally the primary pathway for financing the SDGs, therefore, ought to be increasing government revenue. The SDGs’ financing needs, however, are enormous.

A rough estimate for the cost of a global safety net to eradicate extreme poverty (SDG 1) is around $66 billion annually (Kumar et al., 2016).4 But this estimation is far from complete. The real eradication of poverty requires sustained, inclusive economic growth and job creation. The infrastructure required for this goal—in water, agriculture, information and communications technology, power, transportation, buildings, the industrial, mining, forestry, and fishery sectors—will cost somewhere between $5 to $7 trillion globally (ICESDF, 2014). The UN estimates it will cost $3.9 trillion each year to meet the SDGs in developing countries alone (Madsbjerg and Bernasconi, 2015). Today, public and private funding together cover only about $1.4 trillion, leaving an annual shortfall of

___________________

4 All money amounts are in U.S. dollars unless otherwise noted.

$2.5 trillion—for context, that is more than double the entire 2015 GDP of sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank, 2016a).

Some scholars critique these cost estimates for the SDGs for not going far enough. They argue that the official $1.25 per day measurement of extreme poverty is not actually sufficient for human subsistence (UN, 2009). To achieve a normal human lifespan, meet basic needs, and fulfill their full potential, people need closer to $5 per day (Hickel, 2015). The AU’s stated vision of an “integrated, prosperous, and peaceful Africa” most likely requires a level of investment more in line with this benchmark (AU, n.d.). The vision of a prosperous—and not simply subsistence—Africa, only widens the financing gap. Consequently, even with rapidly revitalized domestic taxation systems to provide a sustainable base of development funding, if the SDGs are to become anything more than a dream they must depend explicitly on the investments of business and civil society (Wall, 2015).

However, the shape that these investments should take remains unclear. A major focus of FFD3 was parsing the different vehicles and financial structures that can contribute to sustainable development. The AAAA reached a consensus on three major areas that circumscribe the means of implementation (MoI) for the SDGs. First, official development assistance and debt relief will continue to be important inputs for many countries (DESA, 2015). Second, developing countries need to mobilize more resources by rapidly enhancing taxation efforts, cutting subsidies, and fighting illicit capital flows (DESA, 2015). And finally, countries—individually or collectively—must tap into new and innovative sources of finance (Bhattacharya and Ali, 2014).

These innovative sources could encompass taxes on financial transactions and the dismantling of tax havens. Resources could be raised from capital markets by floating various medium- and long-term instruments. Global solidarity levies, such as a tobacco levy or a global carbon tax, could also be considered (Bhattacharya and Ali, 2014). On a more local level, public–private partnerships (PPPs) have the potential to play a principal role in health, infrastructure, and urban development projects (Bhattacharya and Ali, 2014). However, MoI are not only financial. The private sector and CSOs will both play a decisive role in ensuring that trade in goods benefits the poorest countries, and that technology transfer aligns with the SDGs (Bhattacharya and Ali, 2014). Ultimately, a key ingredient to the success of each of these innovative MoI is coordination between the different sectors of society. To bridge the SDG financing gap, governments require the investment of business, and to ensure the social benefit of their activities, business requires the guidance of government. The mixed bag of policies and financing vehicles required to meet the SDGs requires partnerships at every level.

The AfDB has repeatedly emphasized that progress toward the SDGs will require the public and private sectors to work together in partnership (AfDB, 2016b) (see Box A-1). In April 2016 the AU held a high-level forum devoted to raising awareness of the synergies between the SDGs and Agenda 2063. Forum organizers were careful to emphasize that

Achievement of these ambitious goals will require leveraging multistakeholder resources, both domestically and internationally, through partnerships with a wide range of actors, including African governments, international development partners, and the domestic and global private sector. (The Africa We Want in 2030, 2063 and Beyond, 2016)

The ECOWAS parliament and the EAC have also highlighted the crucial importance of partnerships and innovative financial mechanisms in pursuing the SDGs (Akosile, 2016; DI, 2015; Osiemo, 2015). Recent workshops with SADC and the UNDP have focused on aligning the SDGs with Agenda 2063, with a specific emphasis on replicating innovations in the health sector across countries (UNDP, 2016). Although the AU, the AfDB, the ECA, the regional economic communities, and national governments have all repeatedly stated the importance of partnerships, any kind of standardized formula for the structure of these relationships remains elusive.

WHAT EXACTLY ARE PPPs, ANYWAY?

In light of the emphasis given to PPPs in Addis Ababa as a pathway to financing the SDGs, it is important to examine the lineage of the concept, and the areas requiring further research. Although PPPs are currently in vogue as a way to increase efficiency, achieve greater value for money,5 and mitigate public risk, they are not a new idea. Concessions, the simplest form of PPP, in which a private company is granted exclusive rights to build, maintain, and operate a piece of public infrastructure, go back thousands of years. In the Roman Empire, concessions were used to construct roads, public baths, and to run markets (Jomo et al., 2016).

Another famous example comes from 1792 France, where the brothers Perrier were granted a concession to distribute water in Paris (Grimsey and Lewis, 2004). In Africa, concessionary companies formed the backbone of colonial European empires. In one illustrative example from the time, the Belgian Congo awarded Lever Brothers, the British soap maker,

___________________

5 The concept of “value for money” represents the ratio of some measure of valued health system outputs to the associated expenditure. See http://www.who.int/pmnch/topics/economics/20091027_smith/en (accessed April 19, 2017).

five concessionary zones to establish palm plantations and processing facilities in exchange for the company’s commitment to build roads, hospitals, and schools for its workers. Although at the time such arrangements were heralded as beneficial for the long-term development of the region, they did nothing to alter the fundamentally Eurocentric structure of the colonial economy (Nelson, 2015).

Since this early history, the PPP concept has evolved considerably, although there is still no universally agreed upon definition (Romero, 2015). The actual term public–private partnership, and the associated modern model of collaboration between the government and a private entity, emerged in the United Kingdom in the 1970s when neoliberal ideologies began to question the poor economic performance of state actors and the dominant Keynesian paradigm (Jomo et al., 2016). The earliest PPPs involved construction projects to develop and renew decaying urban areas. Since then, the concept of PPPs has expanded to encompass joint technology or ecological projects, as well as partnerships to deliver education and health services (Jomo et al., 2016; Roehrich et al., 2014). According to the term’s critics, PPPs have now evolved into a catch-all phrase for any type of collaboration between government and a private entity (Jomo et al., 2016).

In its broadest sense, the ideal PPP exploits synergies in the shared use of resources and in the application of management knowledge to optimally attain the goals of all parties involved (Jomo et al., 2016). In practice, PPPs vary considerably across the degree of ownership and capital expenditure taken on by the private partner (see Box A-2). On one end of the spectrum, with management contracts for public projects, the private entity has little to no capital expenditure. At the other end of the spectrum, with build, own, operate, transfer (BOOT) contracts, the private entity is responsible for all capital financing. In either case, the private partner generates profit either through direct payments from the government or from user charges for delivering a service—or through both. Thus, there can be many variants of PPP schemes depending on the distribution of risk and asset ownership (Roehrich et al., 2014). According to one assessment, “The vast literature on PPPs reveals at least up to 25 different types of PPPs” (Romero, 2015). Not only do international organizations each have their own definitions of PPPs, but different countries are also using their own definitions of the term in national strategies and policies (Jomo et al., 2016). This bewildering variety of possible structures and the lack of clarity encompassed by the PPP concept is a major weakness in devising rigorous and transferable evaluation metrics on the success of partnership projects.

The volume of literature on partnerships is immense, and not all observers are convinced of their efficacy in serving the interests of devel-

opment. Some authors have gone as far as to claim that PPPs, at their core, are a deceptive “Trojan horse” to advance a neoliberal agenda under the guise of sharing power with the poor and the state (Miraftab, 2004). Other authors have highlighted PPPs in the mining sector as a “new renewed imperialism” (Dansereau, 2005). Indeed, evidence on the success of PPPs in advancing development goals is highly mixed. Even more moderate researchers point out that, in many cases, PPPs have turned out to be more expensive than a purely public alternative, and have not provided any measurable benefit to efficiency or quality of service (Jomo et al., 2016). According to the Independent Evaluation Group’s (IEG’s) most recent assessment of the World Bank’s involvement in PPPs across the developing world, over two-thirds of PPPs have been successful—according to the “development outcome rating of project evaluations.” But these evaluations are built primarily on the business performance of the PPPs. Metrics of access, pro-poor aspects, and quality of service are rarely measured (IEG, 2015). Consequently, national governments often cannot assess how much a project has benefited the poor, or even if it provided better value for money than an equivalent public project (Jomo et al., 2016).

Despite their questionable historical legacy and mixed evidence of success in promoting development, African actors such as the AU and the AfDB have moved ahead in pinpointing PPPs as a key to the future agenda (AfDB, n.d.; Tumwebaze, 2016). This decision, of course, does not come without its own long lineage. The idea of partnering for development has been around since at least Agenda 21, an output of the 1992 Rio Earth Summit that championed the formation of multistakeholder “community partnerships” to drive change (UN, 1992). Ten years later, the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg again emphasized the limits to what governments could achieve without bringing civil society, local government, academia, faith communities, trade unions, and numerous other actors—including private enterprise—on board (Evans, 2015). With the formulation of the 2030 Agenda, expectations for a breakthrough in multistakeholder partnerships have reached new heights.

The remaining question, then, is what makes a PPP successful—and how can we measure its success or failure? Ultimately, PPP projects need to be commercially viable to attract private-sector investment, and this affects the sectors in which they are viable (see Box A-3). In terms of the SDGs, PPPs are most appropriate for providing infrastructure (SDG 9 and SDG 11) and for delivering health services (SDG 3).

Trends in Infrastructure PPPs

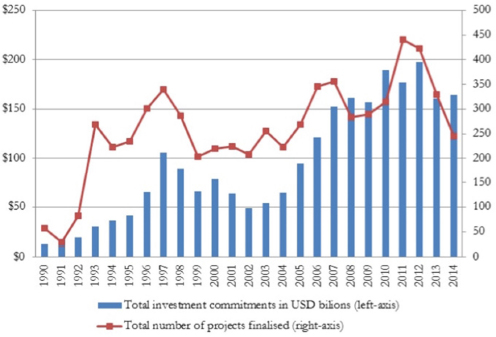

As seen in Figure A-1, the 1990s saw a steady rise in the number of infrastructure projects in the developing world with private participation, and in private financial commitments to these projects. After a small 2-year decrease beginning in 1998, both trends again rose until 2012 (Jomo et al., 2016). The average size of projects also increased from $182 million in 2003 to $322 million in 2013, but they peaked in 2010 at $410 million (Jomo et al., 2016). The increasing size of projects is in line with a global shift to megaprojects in every sector (Flyvbjerg, 2014). Major infrastructure PPPs, with relevance to the SDGs, might include everything from transportation, water, and energy, to information and communications technology, industrial processing plants, and mining (Flyvbjerg, 2014). However, it is important to note that despite the attention given to the private sector, public financing for this infrastructure still dwarfs private involvement. Over the past decade in developing countries, private enterprise has contributed only between 15 to 20 percent of total

NOTE: USD = U.S. dollar.

SOURCE: World Bank, Private Participation in Infrastructure Database available at http://ppi.worldbank.org (accessed May 5, 2017).

infrastructure investment. Given that infrastructure investments make up a major component of the estimated SDG financing gap, private involvement in this sector will likely increase.

Trends in Health PPPs

PPPs in the health sector arose against the backdrop of the public sector’s inability to deliver on desired outcomes, owing to a lack of resources and management issues (Nishtar, 2004). PPPs in the health sector differ from infrastructure projects in that the private partner may be a nonprofit organization. Partnerships with nonprofit, private organizations (i.e., civil society organizations, nongovernmental organizations, foundations, academic institutions) relax the overriding need for a project to be commercially viable, but they impose their own set of complex ethical and procedural challenges (Nishtar, 2004). For example, such partnerships have been accused of fragmenting local health systems, redirecting national health priorities, and undermining social safety nets. In recent years, the picture has been clouded further with many nonprofit foundations funding health initiatives that partner with for-profit providers, introducing many opportunities for conflicts of interest to arise (Nishtar, 2004). Many of the most visible global health initiatives—Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance; and the Drugs for Neglected Disease initiative (DNDi)—are partnerships of this nature (Ratzan, 2007).

PPPs between public health bodies and for-profit companies face the same tension between long-term sustainability and short-term profitability as infrastructure projects. In general, partnerships with for-profit enterprises tend to be susceptible to a selection bias known as “cream skimming,” in which PPPs are more common in large and developed markets to allow faster cost recovery and more secure revenue streams. The result of this phenomenon is that private health investment tends to be focused in relatively affluent urban areas where sufficient resources for efficient and universal public health coverage are already available (Jomo et al., 2016). In Africa, for example, PPPs finance high-tech hospitals in a few urban centers where there are enough wealthy people to support private medicine, but not the universal networks of clinics or the salaries of staff needed to provide health care for the poor (Jomo et al., 2016).

The SDGs, however, will likely be a game-changer for global health funding. With a significantly broader focus than the MDGs, the SDGs could serve to reorient health governance and funding toward previously neglected areas such as noncommunicable diseases and universal health coverage (Huang, 2016). The SDGs’ rights-based approach to health care provision will likely set the developed and developing worlds against

one another over patented medicines for noncommunicable diseases, increasing the complications of partnerships in this sector, and the tradeoffs among health, trade, and intellectual property (Huang, 2016). While global financing partners such as the Gates Foundation are unlikely to shift their focus from malaria and HIV/AIDS in the near future, the SDGs may prompt the emergence of new health partnerships to focus on these new challenges.

MAKING PARTNERSHIPS WORK

Diverse and rigorous partnerships are essential to bridging the funding gaps for pursuing the SDGs and Agenda 2063. The remainder of this brief will outline the available literature that recommends how different actors can contribute to building partnerships for sustainable development.

Governments and PPPs

Governments are the shepherds of the PPP process, giving them a joint responsibility. First, they must create the enabling environment in which partnerships can emerge, and second, they must develop sufficient regulatory and assessment capacity to ensure that projects actually provide a public good (Olsen, 2009). Although CSOs and business have crucial roles to play in delivering the post-2015 agenda, it is world leaders who signed the SDGs, and government has the mandate to meet development goals for their people. There are three activities for governments to undertake to ensure positive developmental outcomes from PPPs, and they all come down to sufficient capacity at the institutional level.

First, governments must be able to correctly identify and select projects where PPPs may be viable (Jomo et al., 2016). Research shows that infrastructure PPPs often suffer from an “optimism bias,” as both sides of the partnership have an incentive to strategically overestimate demand for the project (Romero, 2015). For example, as part of a PPP in Tanzania the state-owned electricity company Tanesco signed a power-purchasing agreement with Independent Power Tanzania Limited. Three government officials approved the project without a proper feasibility study, which would have shown that the problem was not insufficient generating capacity, but a lack of gridlines (Romero, 2015).

Second, governments must have the ability to structure contracts that ensure appropriate pricing and transfer of risk to private partners (Jomo et al., 2016; Murphy, 2008) (see Box A-4). The nature of large PPP projects poses a considerable risk to governments. For example, in the health sec-

tor there is often a public perception that the state should ensure service delivery. If a project fails, which is not an infrequent occurrence, then the government may be forced to rescue the project, shifting private debts onto the public books (Romero, 2015).

Finally, governments must establish comprehensive and transparent accounting and reporting standards for PPPs (Jomo et al., 2016). A key metric for governments to take into account when quantifying the success of a PPP in the health sector, for instance, should be its effect on public health outcomes (NASEM, 2016). The development of PPPs in and of themselves should not be seen as an outcome, but rather as a process and an output toward a social good (Nishtar, 2004). A similar principle applies to infrastructure PPPs; if the desired outcome is increased transportation access, for instance, then this is what should be measured, not the financial success of the partnership. Although social indicators are often difficult to quantify, they must be the ultimate indicator for the success of a project.

Civil Society Organizations and Public–Private Partnerships

CSOs can play a crucial role in localizing development efforts, an area that is often a weak point for governments and businesses. As part of the rollout of SDG implementation plans, the African Civil Society Circle (ACSC) has identified six critical roles for CSOs. First, CSOs often have a closer connection to local people in their arena of operation, and structures in place to listen to the voices of those affected by development partnerships. CSOs can therefore provide a communications conduit between governments, businesses, and local people to ensure that the aims of specific projects and initiatives are clearly understood by their intended beneficiaries (ACSC, 2016).

Second, CSOs have the capacity to translate the voices of the poorest and most marginalized members of society into powerful and well-reasoned arguments in the form of various reports. This role opens the communications conduit in the opposite direction, so governments and businesses can accurately understand the effects of their activities on people’s lives (ACSC, 2016). Third, CSOs are well positioned to form relationships built on mutual trust with local governments. These relationships can help CSOs in their capacity as an intermediary between the government and people, to identify specific problems with project delivery and notify the appropriate official or institution (ACSC, 2016; Chitiga-Mabugu et al., 2014). Fourth, CSOs frequently understand the development landscape through a human rights lens, and they can call attention to groups whose rights have been infringed upon or who have been neglected by the development process (ACSC, 2016). Given the

SDGs stated vision to “leave no one behind,” this capacity is of particular importance (Melamed, 2015). Fifth, CSOs can partner with other nonprofit organizations to facilitate learning and the sharing of best practices. And sixth, CSOs can build the capacity and knowledge of the general populace through training and advocacy processes (ACSC, 2016). By focusing on these six goals, CSOs can position themselves as important partners in working toward the SDGs and Agenda 2063.

The Private Sector and PPPs

The UN has identified private business as essential to the achievement of the 2030 Agenda. In part because the private sector offers an attractive source of funding for a plan that is well out of reach for national governments acting alone, and in part because the activities of private enterprise are entwined with the daily lives and development outcomes of people everywhere. To align themselves with the ambitious agenda put forward for Africa and the world, businesses must learn to go beyond philanthropy and voluntary corporate social responsibility (CSR) toward inclusive and sustainable businesses models—all while maintaining profitability (Neto and Riva, 2015). This is no small challenge.

The very first and simplest way that business can contribute to the post-2015 agenda is by following the principles of good business: obey the law, observe core human rights and labor standards, do not pay bribes, pay taxes, and be transparent and accountable (Evans, 2015). Beyond these basic steps, it becomes useful to focus on specific examples of private-sector involvement in the development process. PPP discussions are often too broad and abstract to be of any immediate use to business. Instead, dialogue between government agencies and businesses should concentrate on analyzing other existing partnerships, and how they might be adapted or learned from for current projects (Evans, 2015). The SDG Industry Matrix, compiled jointly by the UN Global Compact and the international consulting firm KPMG, provides a good example of the type of document that can help in creating PPPs in service of the SDGs. The SDG Industry Matrix focuses on the health care and life sciences sector, and breaks each of the 17 SDGs down into opportunities for businesses operating in that sector, accompanied by concrete examples (UN Global Compact and KPMG, 2016).

As just one example, the SDG Industry Matrix shows that to contribute to SDG 2, a business in the health care and life sciences sector could increase its sourcing of plant, crop, and animal products from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)—like Abbot’s new production facility in Jhagadia, India, that will source up to 80 percent of its ingredients from within the country (UN Global Compact and KPMG, 2016). Examples

such as this help to focus the discussion on partnerships, and inspire the imaginations of those involved. Rigorous analysis of the opportunities available for businesses can help the private sector to incorporate sustainable development indicators into their own internal strategies. This should happen in partnership with governments and CSOs, who often have a clearer understanding of the SDGs and the development situation in their countries (IHRB, 2015).

Clear and universal accountability mechanisms can also go a long way to allay skepticism about whether companies will actually follow through on their sustainability commitments. As one negative example, at the 2006 Clinton Global Initiative, Virgin Atlantic Chief Executive Richard Branson promised to spend $3 billion to fight climate change but according to the activist and author Naomi Klein, by mid-2014 he had spent less than one-tenth of this amount (Evans, 2015). Companies, governments, and CSOs could jointly devise the metrics and mechanisms to report on social impact and resource footprint (IHRB, 2015).

SABMiller,6 the multinational brewing and beverage company, provides a positive example of cooperation between different sectors to design rigorous accountability metrics in line with the SDGs. In 2015, recognizing that the expectations for companies written into the SDGs are high, the board decided to integrate their existing CSR initiative, “Prosper,” into an SDG framework (Swaithes, 2016). Prosper identifies five “shared imperatives” that tackle the development challenges most material to the company’s activities. In their 2016 Sustainable Development Report, SABMiller demonstrates how these five shared imperatives directly align with 11 of the SDGs (SABMiller, 2016b). However, this alignment is only the first step. From there, performance on sustainable development is overseen by the Corporate Accountability and Risk Assurance Committee (CARAC), a committee of the SABMiller board chaired by Dr. Dambisa Moyo, a nonexecutive director of the company, and Zambian-born international economist and author (SABMiller, 2016a). Under Moyo’s direction, regional CARACs meet twice each year to review progress measured by the company’s Sustainability Assessment Matrix.

Transparency is also central to their approach. SABMiller commissioned PricewaterhouseCoopers, a multinational professional services firm, to provide independent assurance over information contained in their 2016 Sustainable Development Report, including water and carbon efficiency, and gender diversity. Additionally, SABMiller asked key global CSOs and partners, such as the World Wildlife Fund and CARE International, to supply commentary on the company’s initiatives, and to highlight areas for future collaboration. This level of transparency not

___________________

6 SABMiller was acquired by Anheuser-Busch InBev on October 10, 2016.

only increases public confidence in the effectiveness of SABMiller’s SDG initiatives, but it allows the company’s strategy to act as a blueprint for other businesses and organizations that want to develop accountability mechanisms.

Ultimately, however, it is important to remember that economic activity cannot be easily redirected to where the need is greatest. The private sector flourishes where the right conditions and opportunities exist, but if those are absent it will not drive inclusive growth (IHRB, 2015). Also, despite proclamations of support for the SDGs or Agenda 2063, companies are not beholden to any development agenda. Government can strongly encourage them, and often will have to oblige them, to adopt practices consistent with sustainable development. While the transformative potential of business is clear to all, other partners should be careful not to treat it as a silver bullet to achieving development. Many countries still lack the right kind political, economic, and social structures to make this transformation possible (IHRB, 2015).

REFERENCES

AAAA (Addis Ababa Action Agenda). 2015. Addis Ababa Action Agenda of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: United Nations. http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/AAAA_Outcome.pdf (accessed June 22, 2016).

ACSC (African Civil Society Circle). 2016. The roles of civil society in localizing the Sustainable Development Goals (position paper). http://www.acordinternational.org/silo/files/the-roles-of-civil-society-in-localizing-the-sdgs.pdf (accessed June 22, 2016).

Adams, P. 2015. Bank to the future: New era at the AfDB (briefing note 1502). Africa Research Institute. http://www.africaresearchinstitute.org/newsite/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/ARI_AfDB_Briefing_Notes_download.pdf (accessed June 22, 2016).

AfDB (African Development Bank). 2016a. Objectives. https://www.africa50.com/about-us/ our-mission (accessed June 22, 2017).

AfDB. 2016b. In Oslo, AfDB calls for partnerships to achieve SDGs. http://www.afdb.org/en/news-and-events/article/in-oslo-afdb-calls-for-partnerships-to-achieve-sdgs-15814 (accessed June 22, 2017).

AfDB. n.d. Public–private partnerships. http://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/sectors/private-sector/areas-of-focus/public-private-partnerships (accessed June 22, 2017).

Africa50. 2016. Africa50 infrastructure fund. http://www.africa50.com (accessed June 22, 2017).

Akelyira, C. A. 2013. Achieving the MDGs in Africa: Should we accelerate? http://www.developmentprogress.org/blog/2013/09/19/achieving-mdgs-africa-should-we-accelerate (accessed June 22, 2017).

Akosile, A. 2016. Enhancing legislative engagement with SDGs across Africa. http://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2016/03/17/enhancing-legislative-engagement-with-sdgs-across-africa (accessed June 22, 2017).

Arimoro, A. E. 2015. Impact of community stakeholders on public-private partnerships: Lessons from the Lekki-Epe concession toll road. International Journal of Law and Legal Studies 3(7). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281286284_Impact_of_community_stakeholders_on_public-private_partnerships_Lessons_from_the_LekkiEpe_concession_toll_road (accessed June 22, 2017).

AU (African Union). 2015. AGENDA 2063, The Africa We Want, A Shared Strategic Framework for Inclusive Growth and Sustainable Development: First Ten-Year Implementation Plan 2014–2023. http://www.un.org/en/africa/osaa/pdf/au/agenda2063-first10yearimplementation.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

AU. n.d. Agenda 2063 vision and priorities. http://www.au.int/web/agenda2063/about (accessed June 22, 2017).

Bhattacharya, D., and M. A. Ali. 2014. The SDGs—What are the “means of implementation”? (briefing 21). Future United Nations Development System. http://www.futureun.org/media/archive1/briefings/FUNDS-Briefing21-SDGsMoI.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

Carter, L. 2015. Five secrets of success of sub-Saharan Africa’s first road PPP. http://blogs.worldbank.org/ppps/five-secrets-success-sub-saharan-africa-s-first-road-ppp (accessed June 22, 2017).

Chitiga-Mabugu, M., Y. Gwenhure, M. Ndokweni, S. Motala, C. Nhemachena, and L. Mashile. 2014. Civil society organisation and participation in the Millennium Development Goal processes in South Africa. Human Sciences Research Council. http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/research-data/ktree-doc/14474 (accessed June 22, 2017).

Dansereau, S. 2005. Win-win or new imperialism? Public-private partnerships in Africa mining. Review of African Political Economy 32(103):47-62. http://doi.org/10.1080/03056240500121024 (accessed June 22, 2017).

DESA (UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs). 2015. Financing sustainable development and developing sustainable finance. http://www.un.org/esa/ffd/ffd3/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2015/07/DESA-Briefing-Note-Addis-Action-Agenda.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

DI (Development Initiatives). 2015. Expert round table forum on East Africa community position on Sustainable Development Goals. http://devinit.org/#!/post/expert-round-table-forum-on-east-africa-community-position-on-sustainable-development-goals (accessed June 22, 2017).

Easterly, W. 2009. How the Millennium Development Goals are unfair to Africa. World Development 37(1):26-35. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.02.009 (accessed June 22, 2017).

ECA (Economic Commission for Africa). 2015a. Africa regional report on the Sustainable Development Goals, summary. http://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-documents/SDG/africa_regional_report_on_the_sustainable_development_goals_summary_english_rev.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

ECA. 2015b. Assessing progress in Africa toward the Millennium Development Goals. http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/mdg/mdg-reports/africa-collection.html (accessed June 22, 2017).

English, M., R. English, and A. English. 2015. Millennium Development Goals progress: A perspective from sub-Saharan Africa. Archives of Disease in Childhood 100:S57-S58. http://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2013-305747 (accessed June 22, 2017).

Evans, A. 2015. Private sector partnerships for sustainable development. In Development Cooperation Report 2015: Making Partnerships Effective Coalitions for Action. OECD. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/4315041ec010.pdf?expires=1470805915&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=4731ED28A60D8219BD1F0CE95D762B91 (accessed June 22, 2017).

Flyvbjerg, B. 2014. What you should know about megaprojects and why: An overview. Project Management Journal 45(2):6-19. http://doi.org/10.1002/pmj.21409.

GKT (General Knowledge Today). 2015, June 3. Union government launches IAP HealthPhone programme. http://currentaffairs.gktoday.in/union-government-launches-iap-healthphone-programme-06201523299.html (accessed June 22, 2017).

Grimsey, D., and M. K. Lewis. 2004. Public private partnerships: The worldwide revolution in infrastructure provision and project finance. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

GSW (Government Spending Watch). 2015. Financing the Sustainable Development Goals—Lessons from government spending on the MDGs. http://eurodad.org/files/pdf/1546383-financing-the-sustainable-development-goals-lessons-from-government-spending-on-the-mdgs.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

HealthPhone. n.d. HealthPhone. http://www.healthphone.org/index.html (accessed June 22, 2017).

Hickel, J. 2015. Five reasons to think twice about the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/africaatlse/2015/09/23/five-reasons-to-think-twice-about-the-uns-sustainable-development-goals (accessed June 22, 2017).

Huang, Y. 2016. How the SDGs will transform global health governance. Council on Foreign Relations. http://www.cfr.org/health/sdgs-transform-global-health-governance/p37482 (accessed June 22, 2017).

ICESDF (Intergovernmental Committee of Experts on Sustainable Development Financing). 2014. Report of the Intergovernmental Committee of Experts on Sustainable Development Financing—final draft. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/4588FINAL%20REPORT%20ICESDF.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

IEG (Independent Evaluation Group). 2015. World Bank Group support to public-private partnerships: Lessons from experience in client countries, FY02-1202-12. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/21309 (accessed June 22, 2017).

Ighobor, K. 2015. Sustainable Development Goals are in sync with Africa’s priorities. Africa Renewal Online. http://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/december-2015/sustainable-development-goals-are-sync-africa%E2%80%99s-priorities (accessed June 22, 2017).

IHRB (Institute for Human Rights and Business). 2015. State of play: Business and the Sustainable Development Goals. http://www.ihrb.org/pdf/state-of-play/Business-and-the-SDGs.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

Jomo, K., A. Chowdhury, K. Sharma, and D. Platz. 2016. Public-private partnerships and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: Fit for purpose? (DESA working paper 148). UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2288desaworkingpaper148.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

Kumar, S., N. Kumar, and S. Vivekadhish. 2016. Millennium development goals (MDGS) to sustainable development goals (SDGS): Addressing unfinished agenda and strengthening sustainable development and partnership. Indian Journal of Community Medicine 41(1):1-4.

Kuwonu, F. 2015. Agenda 2063 is in harmony with SDGs. Africa Renewal Online. http://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/december-2015/agenda-2063-harmony-sdgs (accessed June 22, 2017).

Lawan, S. 2015. An African take on the Sustainable Development Goals. Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/2015/10/13/an-african-take-on-the-sustainable-development-goals/#ftnte1 (accessed June 22, 2017).

Madsbjerg, S., and L. Bernasconi. 2015. Development goals without money are just a dream. https://www.rockefellerfoundation.org/blog/development-goals-without-money-are-just-a-dream (accessed June 22, 2017).

Marriott, A. 2014. A dangerous diversion (OXFAM briefing note). OXFAM. https://www.oxfam.org/sites/www.oxfam.org/files/bn-dangerous-diversion-lesotho-health-ppp-070414-en.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

McArthur, J. 2013. Own the goals: What the Millennium Development Goals have accomplished. Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/own-the-goals-what-the-millennium-development-goals-have-accomplished (accessed June 22, 2017).

Melamed, C. 2015. Leaving no one behind: How the SDGs can bring real change. Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/9534.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

Melamed, C., and L. Scott. 2011. After 2015: Progress and challenges for development. Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/resources/docs/7061.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

Miraftab, F. 2004. Public-private partnerships: The Trojan horse of neoliberal development? Journal of Planning Education and Research 24(1):89-101. http://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X04267173.

Murphy, T. J. 2008. The case for public-private partnerships in infrastructure. Canadian Public Administration 51(1). http://www.mcmillan.ca/Files/TMurphy_caseforP3_Infrastructure_0508.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

NASEM (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine). 2016. The role of public–private partnerships in health systems strengthening: Workshop summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/21861 (accessed June 22, 2017).

Nelson, S. 2015. Concessionary companies. http://www.worldhistory.biz/sundries/26445-concessionary-companies.html (accessed June 22, 2017).

Neto, M. A., and M. Riva. 2015. What role for the private sector in financing the new sustainable development agenda? http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/blog/2015/5/7/What-role-for-the-private-sector-in-financing-the-new-sustainable-development-agenda-.html (accessed June 22, 2017).

Nilsson, M., D. Griggs, and M. Visbeck. 2016a. Map the interactions between Sustainable Development Goals. Nature 534:320-322.

Nilsson, M., D. Griggs, M. Visbeck, and C. Ringler. 2016b. A draft framework for understanding SDG interactions. International Council for Science. http://www.icsu.org/publications/reports-and-reviews/working-paper-framework-for-understanding-sdginteractions-2016/SDG-interactions-working-paper.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

Nishtar, S. 2004. Public–private “partnerships” in health—a global call to action. Health Research Policy and Systems 2(1). http://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-2-5.

Olsen, O. S. 2009. Guidelines for government support to public–private partnership (PPP) projects. Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation. http://www.carecprogram.org/uploads/events/2009/PPP-Workshop-PRC/Guidelines-for-Government-Support.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

Osiemo, F. 2015. Balancing sustainability goals and economic integration in the EAC. http://www.ictsd.org/bridges-news/bridges-africa/news/balancing-sustainability-goals-and-economic-integration-in-the-eac (accessed June 22, 2017).

PPIAF (Public Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility). 2015. PPIAF supports a pioneering transaction in Africa: The Dakar–Diamniadio Toll Road in Senegal. https://olc.worldbank.org/content/ppiaf-supports-pioneering-transaction-africathe-dakar%E2%80%93diamniadio-toll-road-senegal (accessed June 22, 2017).

Ramsamy, R., A. Knoll, H. Knaepen, and L.-A. van Wyk. 2014. How does Africa speak with one voice? Africa’s evolving positions on aid effectiveness, climate change and the post-2015 goals (Briefing note 74). European Centre for Development Policy Management. http://ecdpm.org/wp-content/uploads/How-Does-Africa-Speak-One-Voice-ECDPM-2014-Ramsamy-Briefing-Note-74.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

Ratzan, S. C. 2007. Public-private partnerships for health. Journal of Health Communication 12(4):315-316. http://doi.org/10.1080/10810730701331739.

Roehrich, J. K., M. A. Lewis, and G. George. 2014. Are public–private partnerships a healthy option? A systematic literature review. Social Science & Medicine 113:110-119. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.037.

Romero, M. J. 2015. What lies beneath? A critical assessment of PPPs and their impact on sustainable development. European Network on Debt and Development. http://www.world-psi.org/sites/default/files/documents/research/eurodad_-_what_lies_beneath.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

SABMiller. 2016a. Governance and monitoring. http://www.sabmiller.com/sustainability/how-we-manage-sustainable-development/governance (accessed August 24, 2016).

SABMiller. 2016b. Sustainable Development Report 2016. http://www.sabmiller.com/docs/default-source/investor-documents/reports/2016-sustainability-documents/sustainable-development-report-2016.pdf?sfvrsn=2 (accessed August 16, 2016).

Sumner, A. 2009. Beyond 2015: rethinking development policy. The Broker. http://www.thebrokeronline.eu/Articles/Beyond-2015 (accessed June 22, 2017).

Swaithes, A. 2016. The SDGs - Evolving a common framework for reporting on development progress. http://www.sabmiller.com/home/explore-beer/beer-blog/article/the-sdgs-evolving-a-common-framework-for-reporting-on-development-progress (accessed August 16, 2016).

The Africa We Want in 2030, 2063 and Beyond. 2016. In Early action and results on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, in the context of the first ten-year implementation plan of Africa’s Transformative Agenda 2063: Opportunities and challenges. New York: Office of the Special Advisor on Africa, African Union, Government of Sweden. http://www.un.org/en/africa/osaa/pdf/events/20160420/conceptnote.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

Tumwebaze, P. 2016. Africa: Public-private sector ventures key to devt of Africa’s mining sector, says AU expert. The New Times. http://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/sectors/private-sector/areas-of-focus/public-private-partnerships (accessed June 22, 2017).

UN (United Nations). 1992. Agenda 21. In United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: United Nations. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/Agenda21.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

UN. 2009. Rethinking poverty: Report on the world social situation 2010. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

UN. 2015. The Millennium Development Goals Report 2015. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

UN. n.d. We can end poverty. http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/poverty.shtml (accessed June 22, 2017).

UN Global Compact and KPMG. 2016. United Nations. https://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/issues_doc/development/SDGMatrix-Healthcare.pdf (accessed June 22, 2017).

UNDP (UN Development Programme). 2015. World leaders adopt Sustainable Development Goals. http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/presscenter/pressreleases/2015/09/24/undp-welcomes-adoption-of-sustainable-development-goals-by-worldleaders.html (accessed June 22, 2017).

UNDP. 2016. UNPAN workshop theme: Positioning SADC UNPAN by aligning SDGs and AU agenda 2063 with innovation as an anchor. http://www.za.undp.org/content/south_africa/en/home/presscenter/speeches/2016/06/08/unpan-workshop-theme-positioning-sadc-unpan-by-aligning-sdgs-and-au-agenda-2063-with-innovation-as-an-anchor.html (accessed June 22, 2017).

UNICEF India. 2015. IAP HealthPhone, world’s largest digital mass education programme for addressing malnutrition in women and children, launched in India. http://www.unicef.in/PressReleases/387/IAP-HealthPhone-World-s-Largest-Digital-Mass-EducationProgramme-for-addressing-Malnutrition-in-Women-and-Children-Launched-in-India (accessed June 22, 2017).

Wall, T. 2015. Funding the planet’s future. Africa Renewal Online. http://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/august-2015/funding-planet%E2%80%99s-future (accessed June 22, 2017).

Webster, P. C. 2015. Lesotho’s controversial public–private partnership project. The Lancet 386(10007):1929-1931.

World Bank. 2016a. Sub-Saharan Africa data. http://data.worldbank.org/region/sub-saharan-africa (accessed June 22, 2017).

World Bank. 2016b. Lesotho Health Network public-private partnership (PPP). http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/lesotho/brief/lesotho-health-network-ppp (accessed June 22, 2017).