4

Opportunities and Challenges to Influence Beverage Consumption in Young Children: An Exploration of Federal, State, and Local Policies and Programs

Christina Economos, professor and the New Balance Chair in childhood nutrition at the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy and Medical School at Tufts University and co-founder and director of ChildObesity180, moderated the third session of the workshop. This session offered an overview of policies, programs, and practices at the federal, state, and local levels that affect beverage consumption in large segments of the population, particularly children 0 to 5 years of age. The session also sought to provide insight into the scope of the policies, programs, and regulations, including consideration of the population groups who are and who are not affected or served.

The first speaker, Sara Bleich, professor of public health policy at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, described beverage-related regulations and policies in federal nutrition programs that serve young children. Next, Heidi Blanck, chief of the Obesity Prevention and Control Branch at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Obesity (DNPAO),1 discussed the state and local public health opportunities to support healthy beverage intake. Natasha Frost, senior staff attorney at the Public Health Law Center, then spoke about state-level policies in child care settings. In the final presentation of the session, Kim Kessler, assistant commissioner for the Bureau of Chronic Disease Prevention and Tobacco Control at the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH),

___________________

1 DNPAO is housed within the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion at CDC.

NOTE: SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

SOURCES: As presented by Sara Bleich, June 21, 2017; Oliveira, 2017.

provided a local perspective of New York City’s strategies to reduce sugar-sweetened beverage consumption. A facilitated discussion with the audience, moderated by Economos, followed the presentations.

REGULATIONS AND POLICIES FOR BEVERAGES IN FEDERAL NUTRITION PROGRAMS2

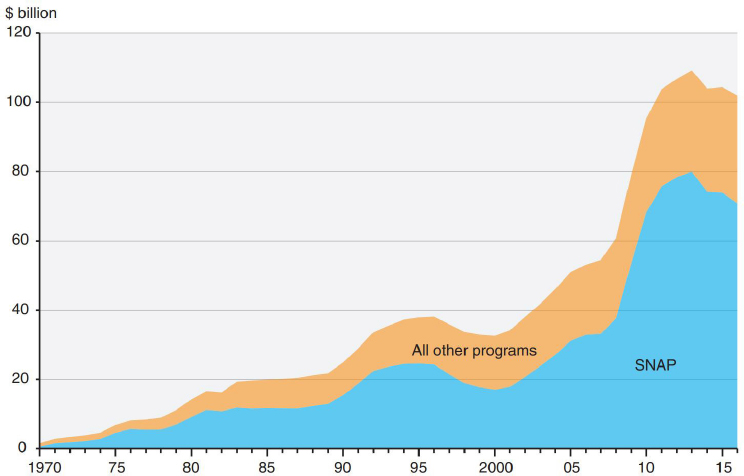

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) administers 15 food and nutrition assistance programs that vary in cost and size, noted Bleich, as she provided context for her remarks. Expenditures for the programs, which exceeded $101 billion in the 2016 fiscal year, have markedly increased since 1970 (see Figure 4-1). Comprising 96 percent of the USDA food and nutrition assistance program spending, the five largest programs in descending size are the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP); the National School Lunch Program; the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); the School Breakfast Program;

___________________

2 This section summarizes information presented by Sara Bleich.

and the Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP). SNAP is by far the largest of the programs, serving approximately 44 million people per month and costing $70.8 billion in the 2016 fiscal year. Bleich pointed out that approximately one in four Americans make use of at least one of the federal food and nutrition assistance programs each year.

Children in the age range of birth to 5 years are served by seven of USDA’s food and nutrition assistance programs. These include the five largest programs, along with the Summer Food Service Program and the Special Milk Program. Bleich provided an overview of select eligibility requirements and demographic characteristics of program participants. She showed that most of these programs have a requirement for participants to have an income equal to or less than 130 percent of the federal poverty level, but noted that WIC uses a higher income criterion of 185 percent or less than the federal poverty level. As compared to the national average, a larger proportion of participants in the programs are black. Highlighting the difference in participation levels in the School Breakfast Program (14.5 million children) as compared to the National School Lunch Program (30.3 million children), Bleich thought there was an opportunity to further leverage the breakfast program to expose more children to healthier options. She also indicated that participation levels vary by state, which she believed created opportunities to enhance enrollment of eligible children. Her assessment of the characteristics of children participating in the programs led Bleich to observe that, apart from statistics on participation levels, comparable data across the programs is challenging to find because information is often siloed in program-specific reports. The lack of uniformed indicators makes it difficult to readily identify data gaps and opportunities, expressed Bleich.

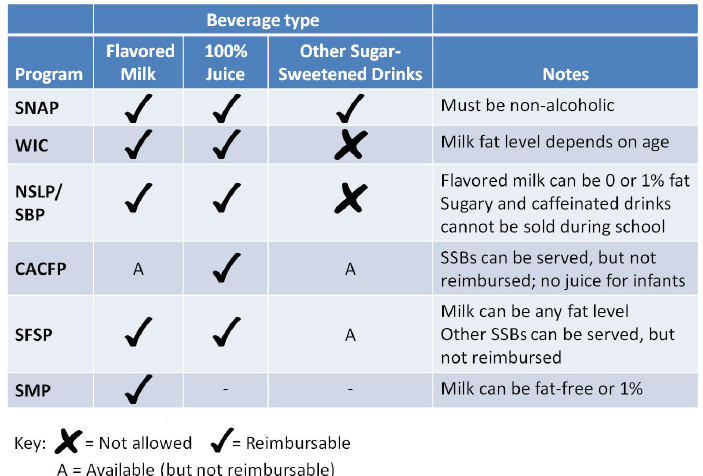

Bleich cited the 2009 update to WIC food packages and the 2010 Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act as two examples of recent changes that created better alignment between program policies and the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. She described the federal policies on sugar-sweetened beverages in the nutrition assistance programs as “setting a floor” that often allows for innovation at the state and local levels. According to Bleich, the beverage policies across the seven nutrition programs are relatively similar (see Figure 4-2). SNAP, however, is the only one of the seven programs that allows sugar-sweetened beverages to be reimbursed. Two other programs—CACFP and the Summer Food Service Program—allow for sugar-sweetened beverages to be served, but do not reimburse for them, Bleich said. She also drew attention to the similarities between the programs’ policies and regulations related to flavored milk and 100 percent juice.

Describing the available data as “imperfect,” Bleich briefly outlined beverage purchase and consumption patterns among SNAP and WIC participants. A recent report found that SNAP households spend approximately 5 cents of every grocery dollar on soft drinks, compared to

NOTE: CACFP = Child and Adult Care Feeding Program; NSLP = National School Lunch Program; SBP = School Breakfast Program; SFSP = Summer Food Service Program; SMP = Special Milk Program; SNAP = Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; SSB = sugar-sweetened beverage; WIC = Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

SOURCE: As presented by Sara Bleich, June 21, 2017.

4 cents per grocery dollar among non-SNAP households (Garasky et al., 2016). Bleich described the evidence as mixed regarding whether SNAP participants consume more sugar-sweetened beverages than those who do not participate in the program. The analysis and interpretation of the consumption data comparing participants and non-participants is complicated by selection issues, as SNAP participants are not randomly selected, noted Bleich. She thought higher consumption among SNAP participants could be more a function of socioeconomic status than program participation. The 2009 revisions to the food packages offered by the WIC program reduced the maximum allowance of 100 percent juice. Findings from Andreyeva et al. (2013) indicate sugar-sweetened beverage purchases declined after the food package change, and do not appear to be compensated for by purchases of other juices and beverages with non-WIC funds. Given its link to weight status, Bleich thought the reduction in the provision of 100

percent juice in the WIC program may have a positive effect on obesity risk of participants.

To conclude her presentation, Bleich provided her ideas for possible areas for improvement. She suggested that a “thoughtful conversation” is needed to discuss the possibility of restricting the purchase of sugar-sweetened beverages with SNAP benefits, and she emphasized that empirical data are needed to understand the effects of such a restriction. Bleich also suggested removing flavored milk as a permissible option in the WIC program. Touching on points she made earlier in her presentation, Bleich thought that participation of children in federal nutrition programs can be enhanced and that opportunities exist to further innovate at the state and local level. She ended by proposing that consistent metrics beyond participation levels across the nutrition assistance programs are needed to understand progress, identify gaps, and find solutions.

STATE AND LOCAL PUBLIC HEALTH OPPORTUNITIES TO SUPPORT HEALTHY BEVERAGE INTAKE3

Early nutrition begins with a mother’s decision to breastfeed, continues as an infant transitions to family foods, and is maintained by those who care for the child outside of the home (e.g., early care and education [ECE] settings, schools), stated Blanck. Accordingly, she framed her presentation around DNPAO’s three priority nutrition strategies that align with this life course concept: getting a healthy start, growing up strong, and maintaining good nutrition.

Getting a Healthy Start

Breastfeeding has been a long-standing priority area for CDC. DNPAO’s work on this topic has focused on enhancing hospital support for breastfeeding women, providing support for employed breastfeeding mothers, and creating community-level support to make breastfeeding a normative and socially supported behavior, especially among low-income and African American women.

Blanck explained that the Maternity Practices in the Infant Nutrition and Care Survey, conducted by CDC every 2 years, largely functions as a “census of hospitals on the maternity care practices that are occurring to support breastfeeding.” Each hospital receives a report of its self-assessment, and each state and territory receives aggregate summaries. Support is then provided to help make the hospitals better aligned with

___________________

3 This section summarizes information presented by Heidi Blanck.

Baby-Friendly practices.4 In 2017, 21 percent of U.S. babies will be born in a Baby-Friendly hospital, an increase from 1 percent in 2005, noted Blanck. Every state, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico each have at least one Baby-Friendly hospital.

Growing Up Strong

Blanck highlighted the role of ECE settings in supporting healthy growth. She briefly touched on the Caring for Our Children guidelines for ECE settings (AAP et al., 2011), which contain 46 standards relevant to obesity prevention that “go across many areas of the caloric balance, including healthy foods and beverages, physical activity, screen time, and breastfeeding.”

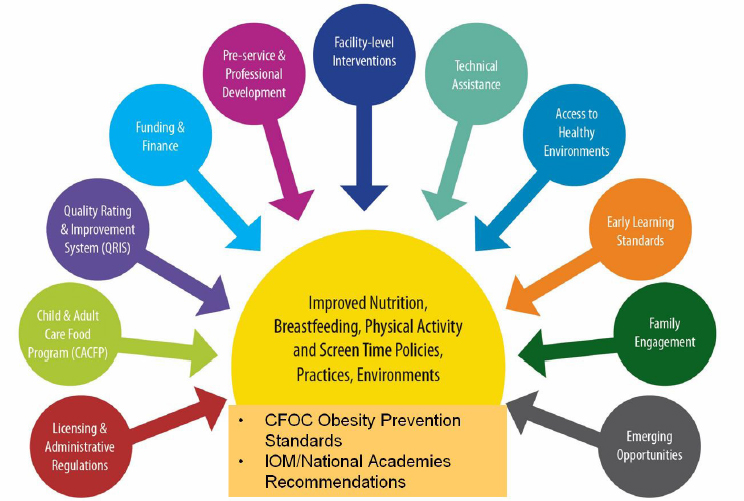

Blanck then presented the “Spectrum of Opportunity” comprised of 11 obesity prevention opportunities that can be employed by state and local ECE systems (see Figure 4-3). Recognizing that the ECE landscape is highly decentralized and variable, DNPAO recently assessed policy and system indicators in every state (CDC, 2016b), as they relate to 7 of the 11 components of CDC’s Spectrum of Opportunity. Blanck provided findings for three of the components: Quality Rating and Improvement Systems (QRISs), professional development, and facility-level interventions.

QRISs exist in 39 states, 29 of which include standards related to obesity prevention. South Carolina, however, is the only state to include language related to beverages. Blanck explained that for a child care program to receive the highest or middle QRIS rating in South Carolina, “sugar-sweetened beverages shall not be served.”

Online professional development opportunities for ECE providers were found in 42 states. Over the past several years, DNPAO has worked to improve ECE providers’ access to low-cost and free training opportunities. One such example is an on-demand healthy beverage module, which as of April 2017, nearly 2,000 ECE providers have taken.

Discussing facility-level interventions, Blanck stated, “Forty-seven states do promote or provide interventions, curriculums, or programs that can support healthy beverages.” Several of the states are promoting self-assessments in family home and child care centers, using such tools as:

- Nutrition and Physical Activity Self Assessment for Child Care (NAP SACC) (UNC at Chapel Hill, 2017);

___________________

4 Hospitals and birthing centers are accredited as Baby-Friendly if they meet specific guidelines and evaluation criteria related to infant feeding and mother–baby bonding practices, care, and support (Baby-Friendly USA, Inc., 2012).

- Let’s Move! Child Care Advanced Checklist Quiz (Nemours Foundation, 2017); and

- Contra Costa Self-Assessment Questionnaire (Contra Costa Child Care Council, 2017).

Blanck also highlighted that DNPAO provides seed funding to ECE settings—18 states receive funding for nutrition-related projects, and ECE settings in all 50 states and the District of Columbia receive funding for physical activity initiatives. In conjunction with the Nemours Foundation, DNPAO has established an ECE learning collaborative to help support planning, development, and implementation of improvements.

NOTES: CFOC = Caring for Our Children; IOM = Institute of Medicine; National Academies = National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. This figure was modified from what the speaker presented to reflect that as of March 15, 2016, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine continue the consensus studies and convening activities previously undertaken by the Institute of Medicine.

SOURCES: As presented by Heidi Blanck, June 21, 2017; CDC, n.d. (modified).

Maintaining Good Nutrition

CDC has released a number of toolkits, guidelines, and frameworks to improve various nutrition environments, explained Blanck. One toolkit, for example, provides guidance on increasing drinking water access in ECE settings (CDC, 2014a). Other resources pertain to the school setting, including addressing competitive foods, promoting healthier options, and increasing drinking water access (CDC, 2011, 2014b, 2016a). More broadly, CDC offers food service guidelines for federal facilities, which Blanck noted can be adapted for “hospitals, parks and recreation venues, worksites, and community vending” (Food Service Guidelines Federal Workgroup, 2017). She also highlighted the Community Health Media Center, which serves as a centralized resource of materials used in CDC’s local community projects that other communities can use (CDC, 2013). The education component of SNAP (SNAP-Ed), noted Blanck, also has a toolkit and evaluation framework of obesity strategies, made available by the National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity Research (NCCOR, 2016). Finally, she shared that the American Academy of Pediatrics offers health care providers Next Steps counseling materials, which include English and Spanish information and activity booklets on a variety of topics, including sugar-sweetened beverages (NICHCQ, 2013).

STATE-LEVEL POLICIES IN THE CHILD CARE SETTING5

Strategic thinking is needed to promote health equity through laws and policies, as “laws and policies have often had adverse effects on some of the most vulnerable people in our society,” began Frost. She suggested that, with the majority of children 5 years of age and younger spending a substantial amount of time in non-parental care, ECE settings represent a key mechanism for early intervention. Frost explained that ECE environments is a broad term that encompasses a range of licensed and unlicensed settings in which child care is provided by someone other than a parent. Her remarks focused on two such environments: (1) child care centers, which are generally located in a facility with multiple staff caring for a greater number of children, and (2) home-based care, which generally consists of one primary caregiver providing care for a smaller number of children in the caregiver’s residence.

Child care settings are primarily regulated at the state level, stated Frost. Every state has different funding streams, quality measures, licensing and administrative regulations, and definitions for what qualifies as a child care center or family child care home. These differences have led to

___________________

5 This section summarizes information presented by Natasha Frost.

a highly decentralized and heterogeneous landscape across the nation and have made drawing conclusions about these settings challenging, observed Frost. State laws underpinning child care settings and ECE quality measures generally do not contain stipulations regarding sugar-sweetened beverages. When they exist, provisions regarding sugar-sweetened beverages in the child care setting are typically found in licensing regulations.

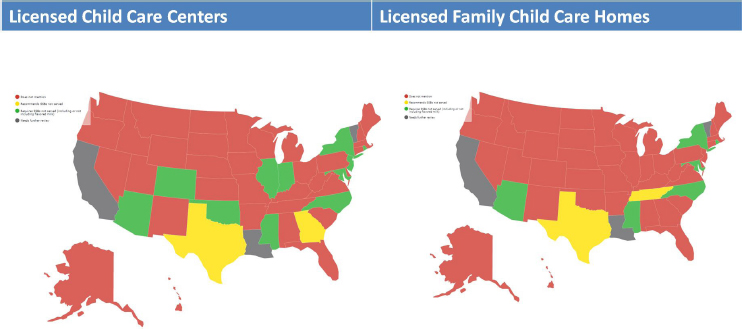

Together with collaborators at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Frost has explored licensing regulations related to healthy eating, active play, and screen time across the United States (Public Health Law Center, 2017). They have found that licensing in most states does not contain a stipulation regarding limiting sugar-sweetened beverages in child care centers or family child care homes (see Figure 4-4). Many states, however, do have nutrition standards that are linked to the CACFP standards, which currently permit sugar-sweetened beverages to be served but not reimbursed. There are states, such as Mississippi, that have created their own nutrition standards separate from CACFP. Frost noted that only a handful of states have licensing regulations regarding serving sizes of 100 percent fruit juice provided in child care settings. In contrast, the vast majority of states re-

NOTES: Red indicates limits on sugar-sweetened beverages are not mentioned in the state’s child care licensing regulations. Yellow indicates the state’s child care licensing regulations recommend that sugar-sweetened beverages not be served. Green indicates that the state’s child care licensing regulations require that sugar-sweetened beverages not be served (may or may not include flavored milk). Gray indicates that further review of the state’s child care licensing regulations is required.

SOURCES: As presented by Natasha Frost, June 21, 2017; Public Health Law Center, 2017.

quire that water be accessible throughout the day or in frequent intervals. “One of the things that we are finding about drinking water is that the implementation is really where it gets complicated,” said Frost. She used Minnesota as an example to highlight possible unintended consequences. Frost explained that child care settings must provide either a water fountain or disposable, single-use cups, which has led to challenges and waste among facilities without a water fountain. She noted that the updates to the CACFP standards, scheduled to take effect in October 2017, also have a provision about water availability.

Frost then broadly discussed policy opportunities and considerations. She cited California’s Healthy Beverage Statute as an interesting model for consideration, as stipulations regarding accessing drinking water and limiting sugar-sweetened beverages exist as a statute rather than in the licensing requirements. Given the variability that exists across states, Frost also emphasized the importance of local context when considering impact. Mississippi, for example, has nine licensed family child care homes, where Minnesota has 9,249 (Child Care Aware of America, 2017). In reflecting on her experience in Minnesota, Frost thought that opportunities exist for advocates and groups working on issues related to nutrition and ECEs to better coordinate with each other and to create a comprehensive strategy for state-level policies. She cautioned that action at the local level may not always be possible, as few states expressly permit local jurisdictions to implement their own nutrition standards. Frost concluded by suggesting additional consideration is needed to define quality in family child care homes, and additional research is needed to explore the role of such child care settings on the provision of sugar-sweetened beverages.

NEW YORK CITY’S STRATEGIES TO REDUCE SUGAR-SWEETENED BEVERAGE CONSUMPTION6

Health inequities exist in New York City, stated Kessler. She showed that neighborhoods with higher premature mortality rates track closely with neighborhoods that have higher concentrations of lower income and non-white households.7 Furthermore, prevalence of obesity and diabe-

___________________

6 This section summarizes information presented by Kim Kessler.

7 Kessler presented maps showing the percentage of the non-white population, the percentage of the population below the federal poverty level, and premature age-adjusted death rates by New York City neighborhood. Sources of the data for the maps were cited as being from the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH) population estimates, matched from U.S. Census Bureau intercensal population estimates, 2010–2013, updated June 2014; American Community Survey, 2013, 3-year estimates, based on events occurring in 2014; population (based on zip code) defined as percent of non-Hispanic black and Hispanic residents, per 2010 Census; neighborhood poverty (based on community districts)

tes among black and Latino adults in New York City are approximately double that of their white counterparts. Adults’ sugar-sweetened beverage consumption varies across the city, and there are higher levels of intake in many neighborhoods with higher rates of diabetes.8 Kessler described the health outcome differences and reductions in life spans as “avoidable, unjust, and unfair.” Accordingly, health equities are a priority area for NYC Health and are being addressed by considering the larger societal context and structural factors involved.

Kessler emphasized that sugar-sweetened beverages are widely available, generally inexpensive, and frequently served in large portion sizes. Such products are also heavily marketed to youth, low-income neighborhoods, and also communities of color, she continued. For example, a 2012 study found that 86 percent of food and non-alcoholic beverage advertisements in supermarkets and bodegas surveyed in the South Bronx neighborhood were for sugar-sweetened beverages. Kessler suggested that even when the marketing is not intended for young children, it can still have an effect by influencing family members who bring sugar-sweetened beverages into the home.

“We do our work with the awareness that even individuals with skills and the knowledge and the desire to make healthy choices will struggle to do so when the environment is working against them,” stated Kessler. To that end, NYC Health seeks to “increase access to and awareness of healthy foods, and also decrease the availability and overconsumption of unhealthy foods.”

One approach New York City is taking to achieve these goals is to promote healthy spaces for children. In 2006, the Board of Health updated the health codes for child care centers. The amendments included requiring appropriate serving sizes for 100 percent fruit juice (6 ounce limit), no longer permitting sugar-sweetened beverages to be served, and specifying that drinking water must be available and accessible. The health code was further revised in 2015, limiting 100 percent juice to children 2 years of age and older and reducing the maximum serving to 4 ounces per day. Similar requirements have been established for day camps.

New York City also seeks to transform its city and community environments. Food standards have been created that apply to the meals and snacks

___________________

defined as percent of residents with incomes below 100 percent of the federal poverty level, per American Community Survey 2011–2013; population (based on zip code) defined as percent of non-Hispanic black and Hispanic residents, per 2010 Census; and self-reported health—NYC DOHMH Community Health Survey, 2011–2013.

8 Kessler presented maps showing the percentage of adults consuming one or more sugar-sweetened beverages per day and the percentage of adults with diabetes by New York City neighborhood. The source of data for the maps was cited as being from the NYC DOHMH Community Health Survey, 2011–2013.

purchased and served by city agencies and city-funded programs. The standards specify that beverages must be 25 calories or fewer per 8 ounces and that drinking water must be available at all meals. The standards also permit 100 percent juice within specific serving size specifications. Standards for vending machines in city spaces have also been established. Kessler explained the city’s food standards have been adapted and used in other settings, including hospitals.

Kessler acknowledged that not all of the broad policy changes proposed by the city have been implemented. For example, a sugar-sweetened beverage excise tax was proposed in 2009 and 2010, but ultimately was not passed by the New York State legislature. In 2011, USDA denied a New York City petition to pilot and evaluate removing sugar-sweetened beverages as an allowable item for purchase with SNAP benefits. New York City also attempted to implement a portion cap on sugar-sweetened beverages, in an effort to “reset the defaults around portion size.” Kessler explained that while these attempts did not result in policy, they did call attention to the issue.

New York City has also used educational campaigns to create awareness. Kessler noted that they have used hands-on nutrition education for the general public in various locations, such as ECEs and farmers markets, to serve low-income New Yorkers. To have a wider reach, New York City has also engaged in mass media marketing campaigns, which have included graphics (e.g., the “Pouring on the Pounds” campaign) and maps that use New York City landmarks to show how far one would need to walk to expend an equivalent number of calories in a sugar-sweetened beverage. Some of the campaigns have been youth focused (e.g., “Your kids could be drinking themselves sick.”).

Kessler reported that there is evidence to suggest sugar-sweetened beverage consumption patterns are changing. Between 2007 and 2015, there has been a 34 percent decline of New York City adults’ daily consumption of one or more sugar-sweetened beverages.9 However, she stated that disparities still persist, as evidenced by racial/ethnic differences in daily sugar-sweetened beverage consumption.10 Kessler reminded the audience that there is no silver bullet for improving diets in general and sugar-sweetened beverages specifically. Therefore, she emphasized the need for crosscutting

___________________

9 Kessler presented adult daily sugar-sweetened beverage consumption data that were cited as being from the NYC DOHMH Community Health Survey 2015, and noted that the definition of sugar-sweetened beverages “includes soda and other sweetened drinks like iced tea, sports drinks, fruit punch, and other fruit-flavored drinks.”

10 Kessler presented adult daily sugar-sweetened beverage consumption data that were cited as being from the NYC DOHMH Community Health Survey 2007–2015. She also presented daily sugar-sweetened beverage consumption data cited as being from the Child Health Survey, 2009.

efforts. Kessler added that surveillance is critical for assessing programs and determining disparities that exist.

FACILITATED DISCUSSION WITH THE AUDIENCE

Economos began the discussion by asking the speakers, “To what extent are those who use the programs brought into the discussion for policy change?” Blanck replied that the Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health program took a community-based participatory approach, a methodology she thought provides “the balance of understanding of what we as scientists think are evidence-based approaches and really the pragmatic feasibility of where community members think there are problems.” Blanck also thought that perceptions of water safety need to be addressed through community input and awareness. She mentioned a study that found a higher distrust of U.S. tap water among Hispanic families, which was associated with higher sugar-sweetened beverage intake. In response to the question, Frost thought it is critical to engage child care providers to help think through implementation of proposed policies.

Economos posed several audience questions related to federal nutrition assistance programs. Speakers were asked their thoughts on whether CACFP should completely remove sugar-sweetened beverages as an option. Bleich thought that reducing exposure makes sense from a public health perspective, but the mechanics of implementation may be challenging. Blanck added that the lack of ECE surveillance data across the nation makes it difficult to understand whether sugar-sweetened beverages are actually being served or offered, and if so, whether it varies by CACFP status.

An audience member wanted to understand why the New York City waiver request for SNAP was denied by USDA. Kessler noted that USDA had indicated that it was because of the complexities of implementing such a waiver. Changing the universal product codes in the system is administratively burdensome, added Bleich. She also stated such a waiver would require having an evaluation plan in place to document the effect of the change. In considering an audience member’s question about how to leverage federal nutrition programs to change the home environment, Bleich further elaborated on the concept of SNAP restrictions. She noted that the notion of SNAP restrictions has been around for quite some time, with strong opinions on both sides of the issue from advocates who care about helping low-income populations. In her opinion, Bleich thought that empirical data are needed to determine the effects of such a restriction and that a pilot trial would need to be authorized.

The speakers also discussed implementing policies and approaches for child care providers who are not located in centers, such as family, friends, and neighbors. Frost emphasized that approaches in such settings are locally

and contextually specific. Funding and resource streams are also important considerations, she added. Blanck noted that one approach CDC has taken for such settings is the free or low-cost professional development modules. She also remarked that home environments have the ability to change much faster than other settings that require formal policies and rulemaking.

Responding to a question about the evaluation of the impact of communication materials, Kessler reported that there is evidence that obesity rates among some young children declined after the child care regulations took effect in New York City, particularly in high-risk neighborhoods. She noted that tracking outcomes related to communication products is much more challenging. Economos also posed a question from the audience about the Healthy Beverage Zone in the Bronx, and its potential as a national strategy. Kessler replied that the initiative is part of a collective impact model, in which NYC Health is one member of a coalition of organizations that are coming together to raise the health status of Bronx residents. She noted that as part of the initiative, organizations can opt into various types of healthy beverage-promoting activities, such as adopting an organization policy or promoting water.