– 2 –

Administrative Records, Third-Party Data, and the American Community Survey

Following brief introductory remarks, the first day of the Workshop on Improving the American Community Survey (ACS) focused on issues related to the incorporation of administrative records or third-party data with the survey’s data collection and production operations. It is essential, then, to be clear about what those terms mean. In the session’s opening presentation, Jennifer Ortman (U.S. Census Bureau) noted that “administrative records” refer to the micro-level data records contained in the working files maintained by government agencies that administer programs and provide services.1 Though much attention has focused on the records compiled by federal government agencies, administrative records data also include records maintained by state, tribal, or local governments. By comparison, “third-party” data refer to similar micro-level data on persons or households by commercial, private-sector entities. Prominent examples of these different data sources—focusing on those that have been made available to the Census Bureau for research—are listed in Box 2.1.

___________________

1 Ortman drew a distinction between administrative records data and the “Systems of Records” that are collected and maintained exclusively for statistical purposes, as the Census Bureau itself does under the authority of Title 13 of the U.S. Code.

2.1 BROAD VISIONS FOR ADMINISTRATIVE DATA USE IN AMERICAN COMMUNITY SURVEY (ACS) PRODUCTION

2.1.1 Outlining the Broad Roles

Jennifer Ortman (U.S. Census Bureau) continued her frame-setting remarks by commenting on the reasons why the Census Bureau is pursuing this change. She said that the Census Bureau is trying to strike a balance between two overarching but contradictory pressures. There remains an insatiable thirst and desire for high-quality data—increasingly demanded at a more rapid pace in order to keep in step with the changing nature of lives and lifestyles. Yet response rates to personal and household surveys have continued to decline for many reasons, among them heightened concerns about the privacy and confidentiality of the supplied information as well as the sheer burden of handling a plethora of information requests. Declining response rates, in turn, have increased the cost of survey work, requiring more attempts to contact potential respondents.

Against this backdrop, Ortman said that the principal substantive reasons for crafting an increased role for administrative records and third-party data in the ACS are three-fold. First is the possible reduction of burden on the respondents: If the Census Bureau has reliable administrative records information for some ACS data items for a particular household, then it need not ask those questions directly. Second, it is believed that greater use of administrative records and third-party data may increase the data reliability of the final ACS product—to wit, data items such as detailed breakdowns of income may be difficult for survey respondents to recall or report accurately in the general survey context, so recourse to IRS data could likely be more accurate. Third, a great promise of these alternative data resources is the reduction of survey cost by decreasing the need for follow-up information, whether the alternative data are used to directly substitute part or all information for nonresponding households or whether they are used to remove from the data collection workload those housing units that are extremely likely to be vacant.2 Ortman also noted that a key practical reason for the Census Bureau to pursue greater use of administrative records data is that it is mandated to do so by the authorizing law for the Census Bureau’s censuses and surveys, Title 13 of the U.S. Code. Specifically, 13 USC § 6(c) holds that:

To the maximum extent possible and consistent with the kind, timeliness, quality and scope of the statistics required, the Secretary [of Commerce] shall acquire and use information available from [federal government, state/local government, or private sources] instead of conducting direct inquiries.3

As described to participants in framing the workshop, and reiterated by Ortman in her remarks, there are three major ways in which administrative records and third-party data may be integrated into ACS production routines:

- Direct replacement of questions and content, omitting some survey questions for households if the same information is reliably available from alternative sources;

- “Filling in the blanks” during survey editing and imputation routines, using alternative data sources to account for nonresponse or discrepant information in specific questionnaire items on otherwise complete returns; and

___________________

2 Ortman observed that this removal of vacant housing units is a major way in which administrative records data will be used in the upcoming 2020 decennial census.

3 The paraphrasing text on sources used here takes the place of reference to “any source referred to in subsection (a) or (b) of this section.” Subsection (a) refers to information from “any other department, agency, or establishment of the Federal Government, or of the government of the District of Columbia” (13 USC § 6(a)) and subsection (b) to “such copies of records, reports, and other material” acquired “by purchase or otherwise” “from States, counties, cities, or other units of government, or their instrumentalities, or from private persons and agencies” (13 USC § 6(b)). This basic language has been a part of census law since Title 13 was codified in 1954, and authority to request information from other government agencies has been part of census law since the 1929 act that authorized the 1930 census (46 Stat. 25).

- Blending ACS and alternative data to generate new data products, using census/ACS and alternative data sources to enrich each other.

Related to these are several other procedural or operational uses, including the previously mentioned notion of identifying vacant housing units up-front in order to better allocate nonresponse follow-up costs. Alternative data sources may also prove important to supporting ACS operations in remote geographic areas and in climates or conditions that may become prohibitively expensive (absent the full extent of resources brought to bear in a decennial census). Finally, another essential role for alternative data sources in the context of the ACS is as a check on the quality of the ACS results: auxiliary or third-party data may provide a useful benchmark or point of comparison for investigating seemingly anomalous findings from survey data.

Ortman said the Census Bureau is convinced that it is worthwhile to pursue this path of greater use of administrative data, including in the ACS, but it is determined to do so carefully and thoughtfully. To that end, she said that the Census Bureau has established a working set of guiding principles or criteria to determine what sources are appropriate for use in the ACS program; these are listed in Box 2.2. Possible administrative records or third-party data sources are assessed with respect to these criteria to determine their suitability for use, in any of the major possible roles. Though the criteria are all important, Ortman deemed quality to be the ACS program’s “North Star,” consistent with the program objectives described by Victoria Velkoff in opening the workshop.

Ortman said that, to date, what the Census Bureau has done in this research area is to evaluate the coverage and quality of a variety of alternative data sources to identify the most promising sources. In particular, and foreshadowing the presentations later in the workshop, the Census Bureau has developed measures of housing characteristics and income—two segments of the ACS questionnaire that have long been seen as most conducive to direct substitution from alternative data sources—to evaluate the possible impact on data products. Particularly in the context of planning for the 2020 census, but certainly with ramifications for the ACS and other surveys, the Census Bureau has also been engaged in testing the use of administrative records data for imputation of the essential demographic information on the census and ACS questionnaires, including race and Hispanic origin and age.

At a high level, Ortman noted, the “big lesson” that the Census Bureau has learned in this research over the past few years is that the work has just started and that major challenges remain to be addressed. One of the guiding principles articulated in Box 2.2 is the consistency of coverage across geography, and that is a particular priority for the Census Bureau because it needs to be fair to all constituencies. Ortman said that the Census Bureau continues to find extensive differences in the coverage across all geographic areas of particular types (state, county, place, and so forth), with records being very complete for some areas

while less complete for others. Great strides have been made in the general ability to link administrative records with census and survey data, but there are always grounds for improvement. Ortman said that the Census Bureau also seeks to improve its ability to better leverage data that were designed for different uses and to become more comfortable in judging the appropriateness of nongovernment sources of alternative data relative to government sources; in particular, nongovernment sources may make changes to their techniques and standards (without public attention or knowledge) that are not fully described and that may affect the resulting data. Finally, as hinted at in the “temporal alignment” guiding principle in Box 2.2, reconciling time lags and differences in the time period covered between different sources remains difficult (for

example, 3-year-old property assessment data might not fully capture something important happening in the domain of housing values).

Ortman closed by noting that leveraging existing administrative records and third-party data sources through linked approaches will be an important component of demographic research, in general, for the foreseeable future, including for census-taking and survey measurement. She said that the field of survey research is shifting, and that alternative data sources should be leveraged to enhance, supplement, or—as appropriate—replace what is currently collected through survey questionnaire items. Accordingly, she said that the Census Bureau is engaging in finding appropriate roles for the use of administrative records and third-party data at all stages of the survey life cycle, and not simply as a replacement for whole questions on the survey.

2.1.2 Census Bureau Internal Evaluation of Alternative Data Sources

Nikolas Pharris-Ciurej (U.S. Census Bureau) described the Census Bureau’s internal research on the aptness-for-use with the ACS of possible administrative records and third-party data sources, taking as a starting point the section of law referenced by Ortman. The Census Bureau is mandated by 13 USC § 6 to use such records and data, to the extent possible, for the efficient and economical conduct of its data collection programs. That passage of law motivates the work of the Bureau’s Center for Administrative Records Research and Application (CARRA), in which Pharris-Ciurej works. CARRA and the ACS Office jointly conducted the evaluation of external data for two pivotal possible roles with the ACS, replacement of questionnaire items and editing/imputation for item nonresponse—and Pharris-Ciurej noted that this analysis is limited to the housing topics on the ACS.

Describing the Census Bureau’s approach to the evaluation problem, Pharris-Ciurej simplified the 12-factor set of guiding principles referenced by Ortman (Box 2.2) into a Venn diagram of four higher-level factors. He said that the analysis is based on the simultaneous use of four broader factors: conceptual alignment, coverage, agreement (of the values of the relevant variables in the records/third-party data and the ACS returns that are able to be linked), and missing data (in the records/third-party source, given interest in using them as possible replacement for ACS values). In general, Pharris-Ciurej argued, the maximum benefit of administrative records and third-party data in the ACS for these purposes depends critically on the respondents’ knowledge or recall of the subject (or lack thereof), on the programmatic purpose of the alternative data source, and the key factor of conceptual alignment between the alternative and ACS sources.

Specifically, Pharris-Ciurej said that aptness-for-use analysis focused on administrative records and third-party sources available for Census Bureau research, as listed in Box 2.1. Using these sources, Pharris-Ciurej said the

Census Bureau’s research team examined possibilities for supplementation or replacement of 14 of the ACS housing items listed in Box 1.1. Summarizing the results, he said that four of the items—property value, costs—real estate tax, year built, and acreage—were deemed “most promising” with the others being “less promising” for ACS–administrative records interface.

Pharris-Ciurej said that the principal reasons for ACS–records integration being less promising for some variables varied considerably. For the Part of a Condominium item, issues of coverage and conceptual alignment proved insuperable. Much of the available data were available using a different level of analysis than desired—the homeowner association (HOA) or co-op level, and not the data about specific units. When data were available at the unit level, they were often for opt-in insurance or mortgage programs, making coverage (and selectivity of units represented in the data) a major problem. Finally, Pharris-Ciurej said that the question is fraught with potential for violating the principle of clear and consistent definitions. A particular confusion is about what is considered a “time-share” relative to a “condominium,” and that there seemed to be considerable variability (perhaps regional as well) in the application of various terms. For the Plumbing/Kitchen Facilities and Phone Service items, the fundamental problem was strongly differential agreement between the ACS and records sources affecting the relatively rare (but critically important) populations who do not have those services. For instance, for cases where linkage was possible between ACS returns and the records, there was consistently strong agreement between a survey answer of “yes” to the presence of phone service and the results in records sources. But if the survey suggested no phone service, records sources were more likely to show discordant values. This led the Bureau staff to conclude that they could not reliably substitute or supplement that information for the full population. Pharris-Ciurej said that difficulties with the Heating Fuel Type item appear to stem from the completeness of the principal alternative data source, the Multiple Listing Services (MLS) data used in real estate transactions. By their nature, MLS data are limited to homes that were recently put on the market or actually sold (and so do not cover all homes), and the MLS data do not cover all markets in the United States. Moreover, Pharris-Ciurej said that realtors tend to list all of the available fuel types in a home listing without indicating which is primary or secondary, so there was misalignment with the ACS question (which asks for the primary fuel type).

Pharris-Ciurej said five other ACS housing items were deemed “less suitable” for replacement or supplementation through administrative records for the basic reason of insufficient detail. The items in question are:

- Agricultural Sales;

- Costs–First Mortgage Payment;

- Costs–Secondary Mortgage Payment;

- Number of Separate Rooms and Bedrooms; and

- Tenure.

For instance, on the tenure item, Pharris-Ciurej noted that the ACS question on tenure has four possible response values4 but the Census Bureau researchers concluded that the administrative records data were only really effective at capturing one of those options.5 He also noted that these items showed the highest agreement on missing values—that is, those items were likely to be missing in both the ACS response and administrative records sources. Pharris-Ciurej’s overview slide identified the yes-or-no Have a Mortgage item as the final “less promising” variable for replacement or supplementation, but he did not explicitly state a reason.

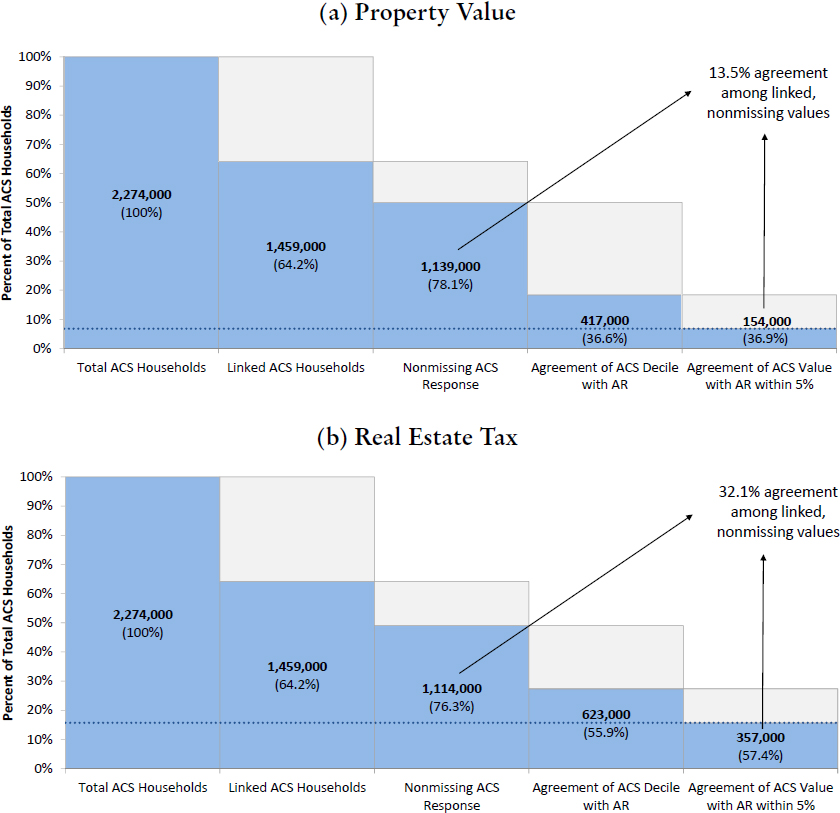

That said, Pharris-Ciurej explained that four ACS housing data items—Property Value, Costs–Real Estate Tax, Year Built, and Acreage—had been found “most promising” in his group’s analysis. He explained the rationale in a series of figures, as shown in Figure 2.1. Part (a) of the figure graphically depicts the level of agreement among linked ACS–administrative records data for the Property Value variable. Of the 2,274,000 base household returns captured by the ACS in 2014, 64.2 percent of them were able to be linked to commercial, third-party property tax data; 78.1 percent of that reduced, linked dataset (1,139,000 households) had nonmissing values for the property value item in the ACS. In the end, 36.6 percent of the linked, nonmissing values for property value were within the same decile and 13.5 percent within 5 percent of each other in numerical value. Part (b) of the figure repeats the analysis for the real estate tax question on the ACS finding a slightly higher (32.1 percent) level of agreement (defined as falling within 5 percent of the ACS-reported value) for that item.

Pharris-Ciurej observed that these percentages might appear disappointingly low, showing “lower agreement than maybe we’d want” between ACS reports and the records. Much of this, he said, is explained by conceptual alignment issues. On property value, the ACS question essentially asks what price the home might get if put on the market now while the commercial data are compiled from the assessments made by state and local governments for taxation purposes; these are sufficiently different ideas to explain differences in the raw values. But Pharris-Ciurej said that the real utility of these data is their coverage of the ACS population. In terms of the capacity for direct substitution

___________________

4 Housing question 16 on the 2018 version of the ACS questionnaire reads: “Is this house, apartment or mobile home—,” permitting the responses “Owned by you or someone in this household with a mortgage or loan? Include home equity loans.,” “Owned by you or someone in this household free and clear (without a mortgage or loan)?,” “Rented?,” or “Occupied without payment of rent?”

5 In his workshop remarks, Pharris-Ciurej did not identify the one response that appeared to perform well.

(replacement of ACS question), Pharris-Ciurej said that the Bureau’s work with the linked sample convinced them that records could provide information for 99.6 percent and 97.0 percent of ACS returns for property value and real estate tax, respectively. Similarly, Pharris-Ciurej concluded, 99.4 percent of missing (unedited) responses to the ACS property value question could be edited/imputed using records data (97.7 percent for real estate tax). Hence, he concluded, the benefits of administrative records for these two ACS data items are compelling, both the high availability of nonmissing data in the alternative sources and the perceived accuracy of government tax data.

On the Year Built ACS item, Pharris-Ciurej said that the Census Bureau had studied agreement in values between 2006–2010 vintage commercial data and the ACS household returns collected in 2012 (2,356,000 households). The Census Bureau researchers linked the files separately by two slightly different geographic identifiers, the Census Bureau’s own Master Address File ID (MAFID) and the basic street address (BSA) for the household. The difference between the two is that the MAFID would be keyed to specific housing units within structures at the address; Pharris-Ciurej said that linking by BSA effectively enables one-to-many linkages between records. Perhaps not surprisingly, they found slightly higher agreement among linked, nonmissing values on the Year Built question when linkage was done at the MAFID level than the BSA level (72.6 percent relative to 68.4 percent). He said the researchers were pleased with the strong general consistency between the ACS and vendor data—particularly because Year Built is “somewhat notorious as a cognitively difficult question for respondents to answer” and so a particularly ripe target for replacement. He said that agreement between the ACS and records value is reasonably high when defined as placing the Year Built within the same 10-year span, 78 percent for MAFID-linked and 76 percent for BSA-linked data. Again, these values may strike some as low—and there are some grounds for completeness concerns, in that linkage appears to be most successful for owned, occupied, single-family metropolitan households than for others. Pharris-Ciurej stressed overall coverage; year built is not something that many respondents may readily know (particularly for renters or apartment dwellers) and so ready access to data with perceived high quality as a substitute cannot be discounted.

The final analysis presented by Pharris-Ciurej was about the Acreage data item. Repeating the same analysis as shown in Figure 2.1 for the acreage data, for linked 2014 ACS and commercial property tax data, the 88.7 percent agreement among linked, nonmissing values is very encouraging. The results hold up fairly well for properties of different sizes, registering 92.8 percent agreement between ACS and records for properties that are less than 1 acre. Pharris-Ciurej said that the Census Bureau concluded that administrative records data could directly substitute information for 95 percent of ACS households, or they could be used for editing/imputation of 78 percent of missing (unedited) ACS responses. For the acreage question, he said that the benefits of records comes in the form of

both high availability of nonmissing data and high rate of agreement between the sources.

Pharris-Ciurej concluded by noting that this is “initial and preliminary” research, suggesting that four ACS housing items appear to be particularly ripe for supplementation through recourse to administrative records or third-party data. Clearly, missing data and conceptual alignment are major barriers for many of the housing data items, preventing even a clear reading of coverage and agreement rates. By the same token, Pharris-Ciurej said that the work had demonstrated that high coverage and agreement rates alone “do not guarantee” the usefulness of the records-based sources; the low numerical agreement between ACS and records values for something like property value need to be weighed in the context of other important attributes such as the confidence attached to the alternative data source, the existence of records-based data for missing survey values, and solid conceptual alignment between the sources.

2.1.3 Discussion

Linda Jacobsen (Population Reference Bureau) opened her remarks, as leader of discussion for this block of workshop presentations, by commending what she described as the Census Bureau’s ongoing commitment and diligent efforts to improve the ACS. In particular, she recognized the Census Bureau’s active search for feedback from subject matter experts and data users through a variety of forums, including but not limited to workshops like this one.

Jacobsen oriented her remarks along four broad themes, the first of which is a paramount focus on assessing data quality. In the quest to determine what administrative records or third-party data sources might be a “gold standard” for comparisons, Jacobsen said that it is important to keep in mind the fundamental concept that all data sources have error—the ACS, administrative records, and third-party data alike. A real “gold standard” of absolute truth is unknowable; Jacobsen said the Census Bureau’s work to date appropriately recognizes that the quality and reliability of administrative and third-party data may vary across geographic areas, and that these alternative data sources may be more accurate or applicable for some population subgroups than others. Picking up on Pharris-Ciurej’s work on the Property Value data item, she said that the variable neatly illustrates numerous conceptual problems:

- Property value is inherently difficult to measure because it is a relative concept—based not on objective, physical measures but rather on the recent sales prices of homes/properties deemed comparable.

- It is, as Pharris-Ciurej said in his presentation, an attribute that is difficult for ACS respondents to process. Jacobsen suggested that many, if not most, ACS respondents might not know with any precision how to answer the question. If someone has been living in a home for a long

-

while and has not contemplated selling it, how would he or she necessarily know the market price?

- The unit of measurement and exact definitions underlying the values in third-party sources need to be reviewed critically: Government assessments for tax purposes are not necessarily a “more accurate” measure of property value as the ACS defines it. Local government assessments are commonly based on neighborhood-level estimates rather than measures specific to the individual property. She used her own neighborhood as an example, in which a recent trend toward “tear downs”—replacement of the 1960s-vintage homes with newer, larger, and more expensive homes—has boosted the assessed value of all the homes in the neighborhood, whether they are a new build or not. Moreover, the third-party property tax data may also rely on estimates derived from statistical models—the exact construction and composition of which may be company-proprietary and hence not transparent, making assessment of the accuracy of the data a difficult prospect.

Jacobsen’s first theme focused on the generation of additional knowledge about the quality and meaning of administrative records data; her second theme was that there is a need to identify more or better ways to share that information. Foreshadowing later presentations, Jacobsen noted that many researchers at the state and local level use administrative data sources in a wide range of applications—and sometimes are responsible for the generation of some of the data. Yet the state and local perspective is perhaps too frequently overlooked, and researchers at those levels may have fewer opportunities to participate in professional meetings and conferences where knowledge of the actual uses of administrative data are shared. Accordingly, she said, there is a need to find better ways for them to share their experience with the broader community—precisely because they are most familiar with the administrative and commercial data that apply to their geographic areas and their specific applications.

Jacobson’s third theme was to recognize that, as Victoria Velkoff noted in her introductory remarks, the ACS faces resource constraints. She said that the Census Bureau needs to have a transparent process for defining criteria and prioritizing across the broad uses of third-party data (substitution, editing/imputation, blending) applied to the range of ACS data items. Some candidate criteria that she suggested might be used are to focus on research and applications that:

- Reduce respondent burden most,

- Increase data quality or reliability most,

- Provide the greatest savings in survey cost,

- Are easiest to implement or are most consistent with new Census Bureau disclosure avoidance procedures, or that

- Have the least negative impact on data users.

Jacobsen’s fourth theme related to her second theme, on garnering state and local practitioner input. Jacobsen urged the Census Bureau to continue to actively incorporate data user perspectives and experience in research and decisions for the survey’s future. Regarding wider incorporation of administrative and third-party data into ACS production, Jacobsen said that it is essential for the Census Bureau to communicate potential changes and their implications to data users in advance of implementation. This is particularly the case if the changes will result in a “break in series” in the time trends for affected ACS variables, of if they will have effects on the availability of the most fine-grained 5-year-average data from the ACS. Jacobsen suggested that it is critical that data user feedback be sought before changes are implemented, in order to assess the possible impact on mission-critical applications of ACS estimates. Doing this effectively will require both attention to documentation of data and procedures and to communication materials and their dissemination strategies. Jacobsen suggested the Census Bureau form active collaborations with data users, particularly those who serve as essential intermediaries in explaining and providing ACS and census data to the broader data user community. And, while the solicitation of feedback before change is implemented is the piece that is sometimes easy to overlook, Jacobsen said that there remains an important need to collect data user feedback after changes have been implemented—to measure the actual impacts on particular applications and to evaluate completely unanticipated effects of the changes.

2.1.4 Floor Discussion

Moderator Michael Davern (NORC at the University of Chicago) opened the floor discussion for this workshop block by picking up on the “gold standard” terminology invoked in some of the spoken remarks—dryly noting that the United States went off the gold standard for its currency in the early 1970s, for good reason. His point, he said, is that agreement between the ACS and the administrative records/third-party sources is good, but the real analytic and policy value is in understanding systematic disagreement between the sources. When asked whether the Bureau is looking into whether and why records and survey data disagree, Ortman replied that the Bureau researchers are very interested in digging into the “why?” behind disagreements. Property value is a good example, and Ortman noted that more would be said in Sandra Clark’s workshop presentation (Section 2.2.1). It is early in the work, but Ortman said that one emerging “bottom line” is that modeling and blending of ACS and administrative records data may prove to be a more practical solution than wide-scale substitution.

Dan Weinberg (DHW Consulting) observed that he had done some work with CoreLogic housing data, and commented that CoreLogic had not really used or exploited the longitudinal structure of the underlying data sources being

combined and modeled in the commercial product. Specifically, there did not seem to be attention placed on longitudinal editing; there might be good year-to-year consistency in some variable except for one unusual spike, but that dominant trend might not be accounted for in calculating a modeled value. He said that this might contribute to the somewhat low agreement rates seen in Pharris-Ciurej’s analysis, and this problem might lend itself to things more sophisticated than year-to-year comparison and concatenation.

Jenny Genser (Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture) asked for comment about the challenge of corralling administrative data from 50 states and the District of Columbia. Ortman replied that this practical difficulty with administrative data plays into some of the guiding principles listed in Box 2.2, including those on data source and geographic coverage. For nonfederal sources, she said that variability among the states (in devoting resources to data collection and sharing) and state and local levels of cooperation are always going to be challenges.

Connie Citro (Committee on National Statistics) said she was particularly struck by Jacobsen’s inclusion of “reducing respondent burden the most” as a lead criterion for identifying research directions. Citro argued that reducing respondent burden is a good criterion, but her opinion is that the Census Bureau’s biggest need is to clearly demonstrate some big “wins” in reducing burden. The ACS items on Year Built and Property Value are questions that can lead respondents to make big, inaccurate guesses. To date, Citro said, the Census Bureau has not put a firm stake in the ground on these points—committed to sunsetting a question or two from the questionnaire if various quality criteria are met for substituting that information from an alternative source. She added that a clear “win” on reducing respondent burden would be good to show Congress (to shore up the ongoing viability of the survey) and to begin to break the pervasive mentality among some that survey data are the paramount or only source of accurate data. Setting a deadline for sunsetting questions, putting that kind of stake in the ground, would give the Census Bureau experience in moving into production with administrative records–based indicators. In reply, Ortman said that the Census Bureau staff would return to this topic at the end of the workshop’s first day, in trying to identify next steps. While conceding that Year Built is an obvious candidate for such a stake in the ground, Ortman said that the Census Bureau was not yet prepared to make that manner of commitment.

Shawn Bucholtz (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development [HUD]) echoed Citro’s call, saying that the Census Bureau and the research community have arguably hit a maturity level with available data on some items, such as receipt of HUD rental assistance or presence of a mortgage, and the generation of a detailed, “companion” microdata file for research purposes could be a useful step. Doing so could get the broader research community to “do some of the hard work” of examining the suitability of the data for imputation or other purposes; such a file could be a good way to elicit help

and feedback, based on actual application of the data. Ortman thanked him for the suggestion. In later colloquy, Stephen Tordella (Decision Demographics) asked whether such micro-level datasets for (external) research purposes would be cleared by the Census Bureau’s Disclosure Review Board. The answer from Census Bureau staff was that this is not known with certainty but that it would be an issue to which the Bureau would be devoting a lot of time. Foreshadowing his presentation later in the day, Robert Avery (Federal Housing Finance Agency) added that he has been engaged in 5–6 years of analysis on available mortgage data, doing extensive matching between administrative sources and survey data. Though results from the survey work are slated to be released in the coming months, he noted that his team has had to redact all geographic detail from their public-facing files—to comply with a privacy review conducted by the Census Bureau itself at the National Mortgage Database project’s request. The reason for the redaction is that mortgage data sources are generally in the public domain, making Federal Housing Agency (FHA) loans very easy to identify based on publicly available data. He did not discount the notion or the value of constructing such a dataset, but observed that it may be important to cast it as a research area and a research-only dataset rather than “pure” public-use microdata files, because a truly public file is unlikely to be effective.

Dean Resnick (NORC at the University of Chicago), building on the general burden question, asked whether it is too difficult to contemplate withholding some questions for individual ACS respondents. That is, he asked if it is feasible to vary the within-questionnaire skip patterns on individual administrations of the survey (depending on what information might be known about a particular respondent household from other sources). The subsequent discussion clarified that this applied strictly to the Internet- or enumerator-administered questionnaire, as custom questionnaires on paper would be unworkable. Ortman said that this approach is something that the Census Bureau is contemplating, albeit for some of the housing data items (asked once of the entire household) rather than the person data items (asked about every household member) on the ACS questionnaire.

Tordella closed the discussion with a follow-up question related to the guiding principle of, and deep concerns about, “conceptual misalignment” between the ACS and the alternative data sources. His comment related to assessing how well the alternative data estimates conform with the concepts defined in ACS questions (and possible alternatives to improve that match). But, he said, perhaps the Census Bureau itself might be better off changing its concepts or definitions, or even “abandoning” them, to better conform with wider, external uses. In discussion, Ortman said that this is certainly something that the Census Bureau is considering—albeit not as strongly as “abandoning” existing concepts. The concepts that a particular dataset actually measures may be distinct from what planners think it is measuring, so attention to both sides (and possible revisions of concept on both sides) are certainly possible. Ortman

said the Census Bureau needs to remain cognizant of the legal or regulatory basis for individual questions (that is, there might be specific concepts necessitated by law or regulation).

2.2 CENSUS BUREAU RESEARCH AND PRACTICE ON ADMINISTRATIVE RECORDS IN THE ACS

2.2.1 Simulating the Use of Administrative Records in ACS Production, for Housing Variables

Sandra Clark (U.S. Census Bureau)6 described the ACS as the “perfect platform” for reliable simulation of the incorporation of administrative records or third-party data into survey responses for a number of reasons, notably the survey’s large sample size and extensive geographic coverage. She noted that this work is meant to be consistent with the ACS program’s goals of providing “reputable, researched, and responsive” products—but also cautioned that the research is just the first step in understanding the possible contributions that third-party data could make in the ACS.

Clark said the simulation began with linking 2015-vintage administrative data with the set of ACS returns from 2015, and focused attention on the four variables deemed most promising for interface with alternative data: Year Built, Acreage, Costs–Real Estate Taxes, and Property Value. It proceeded by matching ACS returns and third-party records and sought to simulate what would have happened if the third-party data had been used for both direct substitution and for editing/imputation, in an adaptive design approach to ACS conduct:

- For 2015 ACS responses via automated modes (Internet, personal interview using electronic instrument, or interview by telephone [that option not yet having been eliminated in 2015]), direct substitution was used whenever possible for the four selected housing data items. For each of the four housing variables in turn, and for every household for which the information was available from the administrative records data, the administrative records value was used instead (thus simulating what would happen if the question had been skipped entirely in the actual interview). If the information for the question was not available in the records data, then the respondent-supplied value was used instead (thus simulating the act of directly asking the question).

- For responses via paper/mail mode, the administrative records match came into play depending on the completeness of response. If any of the four housing data items were missing for a particular household and the information could be retrieved from the administrative data, then the

___________________

6 Sandra Clark acknowledged the contributions of several Census Bureau co-authors to this work: R. Chase Sawyer, Amanda Klimek, Christopher Mazur, William Chapin, and Ellen Wilson.

administrative data value was used. Otherwise, the ACS program’s usual imputation protocols was followed to fill in the missing values.

The administrative records or third-party data used for this simulation were all from the housing analytics vendor CoreLogic. Specifically, the Year Built, Acreage, and Costs–Real Estate Taxes data were drawn from 2015-vintage property tax records compiled by CoreLogic, while the Property Value variable consisted of values calculated from CoreLogic’s proprietary automated valuation model (AVM). Clark said that the Census Bureau chose to use the CoreLogic AVM value after consultation with subject matter experts, including colleagues at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, and she added that the CoreLogic-generated AVM values were probably similar in nature to those used by the online real estate database company Zillow.

Under this design, the analysis compares estimates calculated from the “simulated” or records-augmented data with the actual, “published” 2015 ACS estimates that were released in late 2016. At a high level, Clark said that the work suggested that the substitution does have a distinct effect. The four selected variables are used in 575 estimates (key measures and summary metrics) at the U.S.-level, and 79 percent of those were statistically different; the differences were not uniform, but Clark said that the Bureau noted the tendency, for many items, for the simulated records-based value to be lower than the published value. For each of the four variables, the item allocation rate was significantly lower for the simulated data than the published data—that is, the Census Bureau was less likely to need to resort to “hot-deck” or traditional imputation techniques for these four variables because they were generally more available in the CoreLogic data. This is particularly the case for the Property Value and Costs–Real Estate Tax variables, Property Value dropping from an allocation rate of 12.0 to 5.0 percent between published and simulated data and Costs–Real Estate Tax dropping from 16.9 percent to 4.5 percent. Again at a high level, Clark said that one reason for looking at the four selected housing items is that those questions play only a “small” role in the editing/imputation process for other survey items besides the chosen four. That said, Clark observed that the Bureau had found that the simulated data also led to unexpected impacts in other data items on the questionnaire relative to the published data; notably, incorporation of the third-party data into the Property Value data item did yield a noticeable change in the national-level indicators for Household Income, by way of that small role in editing and imputation.

To suggest geographic variation in differences between the simulated and published values, Clark presented a series of three choropleth maps depicting the percent difference between the simulated and published values for median Property Value, the three maps focusing on the state, county, and place levels respectively. (To make the mapping work, with the available 1-year ACS data, the county-level analysis looked only at counties with 65,000 population

or greater while the place/city map depicted circles scaled proportionate to population size for the nation’s largest cities rather than their geographic boundaries.) At the state level, the simulated value was uniformly less than the published value, the difference appearing particularly large along the Pacific coast (including Nevada), in Georgia and Florida in the South, and in New Jersey. The same pattern generally holds for counties and places, though 16 of the 819 mapped counties registered a simulated median Property Value greater than the published result and 180 of the counties show no statistically significant difference.7 The place/city results were similar to the county results, with an appreciable share of large cities showing no significant difference and a small number of places registering higher simulated median Property Value than published. Clark emphasized that, as had been mentioned earlier in the workshop, the pervasiveness in difference across the geographic levels is not very surprising due to conceptual mismatch issues—the ACS question asking respondents what they think that their home is worth, and that value tending to be an overestimate relative to the tax records and appraisers. That said, Clark pointed out an extreme example in the other direction: the city of Flint, Michigan, in which the simulated median property value was 66 percent higher than the published value. She attributed this to being a case in which administrative data are slow to catch up with a sudden, major shock—in this case, the city’s public health crisis—and deemed it a case in which direct substitution may not be useful. However, one of the ACS’s key conceptual strengths is its ability to provide small-area information, and it is often asked to do so in response to natural disasters and other local events, so the possible time-lag effect suggested by Flint—administrative records perhaps not registering sharp and sudden devaluation—might sound a cautionary note for direct replacement of items using administrative records data.

In order to roughly measure potential reductions in respondent burden, Clark said that her group’s analysis classified 2015 ACS responses by match status, judging them a “match” if the ACS-responding household had a corresponding administrative records-based value for any of the four tested questionnaire items and a “non-match” otherwise. Examined by state, Clark said this overall match rate ranged from 78 percent (Iowa) to 9 percent (Maine), with the rate being over 50 percent for the vast majority of states. Then, for each of the four tested housing variables in turn, the “match” ACS respondent households were further classified as:

- Burden reduction, meaning that there is an administrative records value for that particular variable and that particular household, obviating the need to ask the question in an automated interview;

___________________

7 At the workshop, the number of counties with no statistically significant difference was reported as 181. After the workshop, in finalizing the research, the figure was revised to 180.

- Potential mail burden reduction, meaning that there is an administrative records value for that particular variable and household but the household responded by mail/paper questionnaire, and so would not represent a burden reduction unless the mail/paper mode “adapted” as well; and

- Match—value not available, meaning that the match was to at least one of the other three tested variables.

Plotting these match rates as stacked bar charts, separately by each variable, showed considerable variation among the states, a small number of states being particularly prone to missing administrative records values for Property Value or Year Structure Built (and so registering “Match—value not available” for that variable). Clark characterized it as “many” states having greater than 50 percent “burden reduction” match rates in each of the variables. Fairly pervasive bands of up to 20 percent of respondent households being “potential mail burden reduction” suggests to Clark that including this kind of adaptive design in the mail/paper mode could have strong benefit—but would also be very difficult to manage (and for cost reasons). Clark briefly presented similar stacked-bar charts for the county level, with similar visual impressions arising: encouraging, greater-than-50-percent overall match rates being the norm, but with more variability and less compelling burden reduction rates when examined by separate variables (with Year Structure Built and Property Value, again, performing most poorly). Clark demonstrated that mapping the county-level burden reduction rates by each question hints at the administrative records data being generally more complete and available in more populous, urban counties. Rural areas, generally, appear to be more dependent on the mail/paper mode of response to the ACS, she said. Overall, Clark calculated the burden reduction at the national level at 52 percent for Acreage, 54 percent for Costs–Real Estate Tax, 47 percent for Property Value, and 38 percent for Year Built.

In recapping the major challenges encountered during this work, Clark began by conceding the inherent uncertainty associated with reliance on an outside vendor in CoreLogic. Contracts, prices, and methodologies are all subject to unexpected change; new vendors can always come into the equation; and there is always a risk associated with depending on the output of CoreLogic’s (or any particular vendor’s) undocumented and proprietary automated valuation model as the “best” alternative source of property value data. The county-level analysis underscores that the completeness of administrative data differs across jurisdictions, making the data unavailable for some areas and types of housing units. Moreover, Clark said there may be important differences in analysis created by time lags between economic developments and their becoming manifest in survey versus administrative records data. Though linkage methodologies have improved markedly in recent years, Clark said it is sometimes difficult to impossible to link records to survey data (and that

improved linkage techniques remain an important research area). Given the Census Bureau’s mission to treat all jurisdictions and potential respondents equally, Clark said that there is the lingering challenge to effectively adapt data collection techniques in all modes (particularly difficult for mail/paper); implementing any of these changes involves major changes to the entire survey life cycle, requiring significant resources and extensive testing to minimize risk. Finally, a recurrent theme throughout the workshop, Clark said using administrative records can complicate the application of new data disclosure avoidance rules.

As a preliminary conclusion, Clark said that she and the Census Bureau team had concluded that full incorporation of administrative records or third-party data for any of these four tested housing data series would create a “break in series” relative to earlier years of data. This simulation work underscored that administrative records data and ACS response data are simply so “different” from each other—neither uniquely better nor uniquely worse but simply different—that such a break is virtually inevitable. Such a “break in series” is not something that the Census Bureau takes lightly; there would also be a ripple effect on other survey items, and differential availability or quality of the records sources could “unfairly represent” some geographic subgroups (particularly if used for direct replacement of questionnaire items). But, Clark said, the potential benefits are too compelling to neglect: significant reduction in respondent burden and great improvement in item allocation rates.

2.2.2 Comparison of ACS-Based and Administrative Records-Based Indicators of Income

Jonathan Rothbaum (U.S. Census Bureau) began his remarks with a basic comparison, using estimated, national values for selected income types (earnings, property income, transfers/pensions and retirements, and overall). These values from two different Census Bureau-conducted surveys—the 1990–1996 and 2007–2012 averages from the Current Population Survey (CPS) and the 2007–2012 averages from the ACS—were compared with the relevant aggregates in the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) maintained by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA). In terms of earnings, Rothbaum said that the different, relevant Census Bureau surveys “generally capture most of the dollars” in the BEA figures—90 percent or more—for several types of income, but that other types of income are more challenging. For instance, he said that the ACS average captures only about half of the relevant activity for property income. The ACS does not delve into income in the same detail as the CPS, so the ACS measure of transfers (primarily Social Security income, but other sources as well) also includes pension and retirement income that the CPS

is capable of estimating separately. But, on balance, the survey-based measures capture 80 percent or more of the BEA NIPA values for transfers.8

At the most aggregate level, Rothbaum said survey-based measures do well on earnings and Social Security income and less well on other income types—but, he added, the interest in this area of research is how well the comparison works on individual/household records and at lower levels of aggregation. Rothbaum briefly described the Census Bureau’s process as probabilistically linking individuals to, effectively, Social Security numbers using name, age, and other characteristics. Identifying information is removed and replaced with a Protected Identification Key (PIK), which then becomes the basis for final matching and linking. Each year, Rothbaum said, 7–9 percent of the individuals in the ACS sample are not linked to their Social Security numbers, are not able to be associated with a PIK, and so are unlinkable to individual administrative data. For actions such as direct replacement, he said, as much as 9 percent is not linkable to alternative income data from records sources.

Rothbaum cited the O’Hara et al. (2016) analysis of linked 2011 ACS returns and Internal Revenue Service (IRS) W-2 forms in concluding that a high correspondence exists between the existence of a W-2 (earnings reported to the IRS) and earnings being reported (nonzero) in the ACS. Specifically, 52 percent of the linked set were found to have both a survey response to the earnings question and a W-2 on file, 38 percent had neither a survey response on earnings nor a W-2 on file, and the one-but-not-the-other combinations split the remaining 10 percent of the linked data. Rothbaum noted these percentages are comparable to those using CPS data, for which there is not necessarily the mismatch in time periods between W-2 (calendar year) and ACS (last 12 months) data. Also citing O’Hara et al. (2016), Rothbaum observed that the response values are strongly correlated as well; plotting the logarithms of total wages from the 2011 ACS and W-2 returns yields a reasonably good linear fit though not quite one-to-one correspondence; for lower-income respondents, the value reported to the ACS tends to be higher than the value on file in the W-2. He added that this is not necessarily misreporting and that, particularly at lower levels of income, there are reasons for not reporting income to the IRS, but it needs to be borne in mind in examining poverty through survey and administrative data. Rothbaum described investigation of these differences as a very active research area for the Census Bureau, alluding to additional research in the literature suggesting some tendency toward misreporting among males (especially, again, at low incomes) and among more educated respondents.

Rothbaum cited analysis of 1997 data from the CPS Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC), rather than from the ACS, to illustrate that similar patterns hold for Social Security income and retirement income, but with critical deviations. Using matched survey and Social Security

___________________

8 Rothbaum cited his own Census Bureau report (Rothbaum, 2015) as the source for the figure.

Administration payment records, 87 percent of cases showed a nonzero survey response for Social Security income and a record of payment in the administrative records—and, as with earnings, the actual reported values are strongly correlated for that subset of cases. Put another way, Rothbaum said, Social Security recipiency as measured by the survey appears to be accurate, subject to low Type II error. But he added that nonrecipiency is subject to high Type I error when measured by survey; only 5 percent of the matched cases registered both a survey report of zero Social Security income and no SSA record of payment. (About 4 percent of the matched cases fell into the off-diagonals, instances of the survey showing zero SSA income but nonzero payment in SSA records or vice versa.) And if the results for Social Security income “look bad to you,” Rothbaum cautioned, then “don’t look at retirement income,” where the picture is worse. Based on analysis of matched 2009 CPS ASEC data with IRS form 1099-R records, nonrecipiency in the 1099-R data is overwhelmingly likely to correspond with nonrecipiency in the survey data. Rothbaum said only 45 percent of recipients in the administrative/1099-R data also report retirement income in the survey, meaning that a majority do not. Part of this is confusion on the reporting of 401(k) funds, Rothbaum said, but not all—remarking that this amount of difference has a “huge impact on how we measure income” for persons age 65 and older. Rothbaum said that survey-based measures of income for the 65-and-older population are roughly 30 percent too low (household median income, when the head of household is 65 or older) and measures of poverty are 2–2.5 percentage points too high. Rothbaum said that the same holds true when looking at other income types, such as receipt of SNAP or TANF benefits. Still, Rothbaum made the general assessment that earnings and Social Security are generally well reported in the data, that the quality and degree of reporting varies for other types of income, and that underreporting and misreporting can be severe. But, he said, even in those cases, conditional on their reporting a value on the survey, that value tends to be relatively accurate.

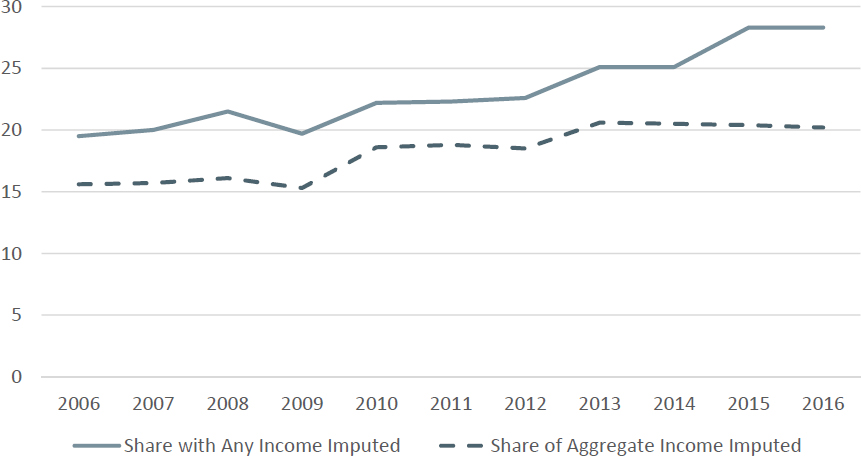

Turning to the possibilities of using administrative records data to deal with survey nonresponse (whether whole-unit or individual-item), Rothbaum began by illustrating the extent to which income data have had to be imputed in part or in whole in the ACS over the years. Figure 2.2 shows his calculations from ACS data files, showing a general increasing trend over the past decade of 20–30 percent of individuals in the ACS sample needing to have part of their income imputed for nonresponse; in dollar values, imputation has accounted for 15–20 percent of aggregate personal income. Rothbaum suggested that these values are actually reasonably good given the dominant trend toward increased survey nonresponse, and that the picture for the CPS ASEC appears considerably worse (the ACS benefiting from its mandatory-response status). Analysis of those CPS ASEC data do suggest some general patterns to consider in the ACS context; Rothbaum noted that the CPS ASEC shows markedly

higher nonresponse for the highest and lowest income percentiles (which has implications for the accuracy of imputation in general). He said that research that he has participated in regarding income imputation in the CPS ASEC suggests a tendency to consistently overstate average income when using administrative data in imputing for nonresponse.

Having raised some of the underlying conceptual issues and basic findings from his research, Rothbaum quickly reviewed the table reproduced in Table 2.1. He said that the table asks, for various components of income requested on the ACS questionnaire, three basic questions: What are the data that the Census Bureau have, what are the data that might be useful, and what are some of the concerns? Some of the things noted in the comments and “concerns” column are recurring themes and challenges in the measurement of income in general. For overall earnings, a major concern is unreported earnings that do not appear on individuals’ W-2 forms for a variety of reasons. For income specifically from self-employment, he said that evidence from surveys of consumption generally show spending among the self-employed to be much higher than the self-reported income value would suggest, raising concerns about the accuracy of either administrative records or a general survey like the

ACS to capture that specific income type. And, for dividend income, Rothbaum said that the major challenge is that the administrative data are largely limited to the existence of a return rather than the content. But, conversely, Rothbaum said that administrative records information on Social Security income might be as close to a “gold standard” as possible: if the Social Security Administration does not have a record of someone getting paid a benefit, they probably were not paid the benefit.

Before presenting his analysis, Rothbaum alluded to ongoing cognitive testing being done by the Census Bureau on burden reduction specific to the income data items. In particular, one thread of the research starts with the premise that the task of providing the full breakdown of income by type might be too difficult and might detract from the accuracy of reporting of overall income, so the cognitive testing work is considering variants of the ACS questionnaire that ask yes/no for recipiency of certain income types only (not the individual amounts), with total income being the only dollar-value income amount requested. Another part of the cognitive testing work attempts to change the relevant reference period, asking respondents to describe their income in the prior calendar year rather than just the previous 12 months from the date of the interview. The work is ongoing, so it is not known what effect the change might have in accuracy.

As Rothbaum described them, the basic approaches for reducing respondent burden associated with the income questions on the ACS, via direct replacement, involve different thresholds for performing that replacement. One approach would be to drop the income-type-and-amount questions for everyone (or nearly everyone) in the ACS sample, substituting administrative records values for the “missing” income-breakdown information as possible. The detailed income questions could still be asked of a subsample of respondents, and those responses (or those from another income survey such as the CPS ASEC) could be used with other ACS covariates and administrative records information to model survey responses to the income question for the full sample. Variants on the modeling with replacement approach would be more aggressive in modeling/replacing additional income types, or use “universe” administrative record data and ACS sample to generate estimates that are more precise and specific to geographic/demographic subgroups.

To approximate these approaches, Rothbaum described constructing and analyzing two different files. His Survey-Only File retains ACS income-question responses for about 3 percent of the ACS sample (a level he said that he based on the size of the CPS ASEC sample relative to the ACS). Rothbaum used those responses and administrative records (IRS Form W-2, 1040, and 1099-R entries) to construct regression models that were then used to impute income recipiency and value responses for the remainder of the sample. He noted in brief that the estimation was done sequentially, opting to model a first income type using only the other ACS and administrative records characteristics, but including

| ACS Data Item | Available to Census Bureau? | Other Useful Sources | Issues/Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wages, salary, commissions, bonuses, or tips from all jobs. |

W-2s Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics (LEHD) 1040s |

National Directory of New Hires (NDNH) |

Unreported earnings. Note that only UI records from LEHD capture GROSS earnings before any deductions. Amounts excluded from income such as employee health premiums do not show up on any IRS forms. |

| Self-employment income from own nonfarm business or farm businesses, including proprietorships and partnerships. |

1040 Schedule SE (only receipt, not amount) 1040 Schedule C (only receipt, not amount) |

1040 schedule amounts 1099-MISC |

Unreported earnings. Evidence from consumption surveys and audit studies suggests substantial under-reporting of income in both surveys and administrative records. |

| Interest, dividends, net rental income, royalty income, or income from estate and trusts. |

1099-DIV/INT (incidence, some years) 1040 Schedule B (interest and dividends) 1040 Schedule E (rental and royalty income and income from estates and trusts)—gross only 1040 Line 8a and 8b for tax-exempt and taxable interest, Line 9 for total dividends all ACS year |

1099-DIV/INT amounts 1040 Schedule E net rental income 1041-K1 for rental income 1040 Line 17 Rental, royalties, estates/trusts (must be filed if estate and trust income present) |

Missing Interest and dividend payments under $10. Only gross rental income currently available on 1040s. |

| ACS Data Item | Available to Census Bureau? | Other Useful Sources | Issues/Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social Security or Railroad Retirement |

SSA-1099 (incidence, some years) 1040 (this is total Social Security benefits not the taxable amount) |

SSA-1099 (amounts and incidence for other years) SSA Master Beneficiary Record and Payment History Update Files 1099-RRB |

1040 SS data is of questionable quality in earlier years of ACS. Having only the Social Security data, without SSI data is problematic for income replacement given program confusion in reporting. |

| Supplemental Security Income. |

SSA SSI (incidence) |

SSA SSI (amounts) |

This is not taxable, so SSA is the only possible source for this information |

| Any public assistance or welfare payments from the state of local welfare office. | TANF |

This is not taxable so states are the only possible source of this information. Available with full coverage in some states, sample in others, with no data from many states. Not clear whether it is feasible to gather information on local government programs. |

|

| Retirement, survivor, or disability pensions. |

1099-R (This should include nontaxable benefits and some disability) |

SSA-1099 (Social Security Disability and survivor benefits) 1099-MISC (Employer/Union paid survivor benefits) W-2 (Short-term disability payments, not on the current W-2 received) Veterans’ Disability/Survivor: VA (not taxable) 1040, Schedule R for disability payments |

| ACS Data Item | Available to Census Bureau? | Other Useful Sources | Issues/Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any other sources of income received regularly such as Veterans’ payments, unemployment compensation, child support, or alimony. |

Unemployment: 1099-G (incidence, some years) |

Unemployment: 1099-G (amounts and incidence for other years) Alimony: 1040 Line 11. Other Income: 1040 Line 21, Includes: Nonbusiness credit card debt cancellation, which can be netted out with 1099-C if not desired); Prizes and awards; Gambling winnings; Jury duty pay; Alaska permanent fund dividends Educational Assistance/Pell Grants: 1098-T Veterans’ Payments: VA (not taxable) |

Child support, financial support, not covered in tax forms (available in survey data for modelling. People do get wages garnished who fail to pay child support so there is some record keeping of this that may be worth exploring) Workers’ Compensation: some taxable/some nontaxable, available for modeling from CPS ASEC. There may be some trail for nontaxable income in W-2 filed workers’ compensation that is subtracted from 1040 on line 21. Other WC is considered taxable wages in the W-2. |

SOURCE: Workshop presentation by Jonathan Rothbaum.

recipiency of income type 1 in the model to estimate income type 2, including recipiency of income types 1 and 2 in the model to estimate income type 3, and so forth. He replicated this analysis for each year, 2006–2013, to examine temporal consistency in results. His second analysis file, dubbed the Model-Replacement File, used the Survey-Only File as the base but was more aggressive in replacing ACS-reported values with administrative records information that are a rougher match to the ACS concepts. In particular, this involved making even fuller use of W-2 and 1099-R data for some categories (e.g., using Form 1040 data on adjusted gross income to measure total household income if the 1040 exists). Rothbaum mentioned making use of IRS Form 1040 information on gross income from rent in lieu of the ACS-requested data on interest and dividends earnings—something that he said is thought to “vastly overstate” that type of income but that nonetheless would be a good test of utilizing those available data—but the conceptual mismatch is too great to bridge for this current work.

The results were consistent with the themes already outlined, Rothbaum said. Looking at ratios of total household income, modeled Survey-Only File to the published ACS results, across percentiles of the income distribution for a single survey year, the ideal result would be a flat-line ratio of 1. Rothbaum generally found that this is the case for middle to large percentiles of the income distribution, but the line distinctly dips below 1 for the lowest income percentiles relative to the published ACS rsults. That is, the modeled, administrative-records-based measures tend to understate income (and overstate poverty) at the lowest percentiles relative to the published ACS results. This result generally holds for all years at the national level and across states. Results from the Model-Replacement File yield an even more exacerbated gap for the lower income classes. Analyzing the years separately, particularly for the file where substitution of 1040 adjusted gross income is more liberal, shows an anomaly similar to the time lag Clark noted in her data (see Section 2.2.1). In the pivotal recession year of 2008, there was more incentive/reason for households to file a zero-income 1040 return, causing a massive number of 0 values not seen in 2007 or 2009—and consequently an even greater divergence from the ACS-published estimates for the lowest income percentile.

Summarizing, Rothbaum cautioned that measurement error can bias estimates of the income distribution, primarily because respondents tend to underreport recipiency; that two major types of income, base earnings and Social Security income, are fairly well represented in administrative records data but other income types are more challenging; and that even those well-covered income types are prone to be discrepant at the lowest levels of income. There are high-quality sources of information that might be brought to bear—detailed IRS data from Form 1040 and 1099 returns on property income and Social Security Administration payment records—but that are not currently available for work with the ACS. Initial research on simulating the effect of

substitution or editing/imputation for ACS income responses suggests promise but also noisy estimates at the state level—likely even more so at smaller levels of geography—echoing Clark’s observation about needing to manage the impact of breaks-in-series when alternative data are incorporated into ACS production.

2.2.3 Planned Use of Administrative Records in the 2020 Census for Imputation of Characteristics, and Possible Extensions to the ACS

Andrew Keller (U.S. Census Bureau) discussed steps being taken to impute key characteristics—age, race, and Hispanic origin—due to nonresponse. They are premised on the decennial census, but have potential applications in the ACS that remain to be explored. Specifically, he said the 2010 decennial census enumerated roughly 308 million people across 136 million addresses. Addresses that were not resolved during the self-response phase of the 2010 census were turned over for in-person, nonresponse follow-up (NRFU) contacts. In 2010, NRFU operations applied to about 50 million of the 136 million in the universe, and the cost of mounting the NRFU operation alone was on the order of $2 billion. Nonresponse on the characteristic-information questions can happen in both the self-response and NRFU populations, and Keller noted that about 7 percent of age/date of birth values, 6.4 percent of Hispanic origin, and 6 percent of race values in the 2010 census had to be imputed. Keller noted his understanding that these percentages are “in the ballpark” of levels of missing data for these items in the ACS.

Given the cost of in-person NRFU operations, Keller said that increased use of administrative records or third-party data is seen as a “key innovation area” to reduce the cost of NRFU while maintaining data quality. One critical way in which Keller said that the 2020 census is at the unit level, using administrative records to remove some vacant housing units from the NRFU workload up front. Another approach is to directly fill information for occupied households if there is high confidence that records can reliably provide all the requisite census information for those units. This work has been developing since the early part of this decade and began to be tested as early as 2013. The Bureau is also pursuing work at the person-level; the evaluation study corresponding to editing and imputation in the 2010 census urged that the Census Bureau explore a wider use of administrative records information in those algorithms.

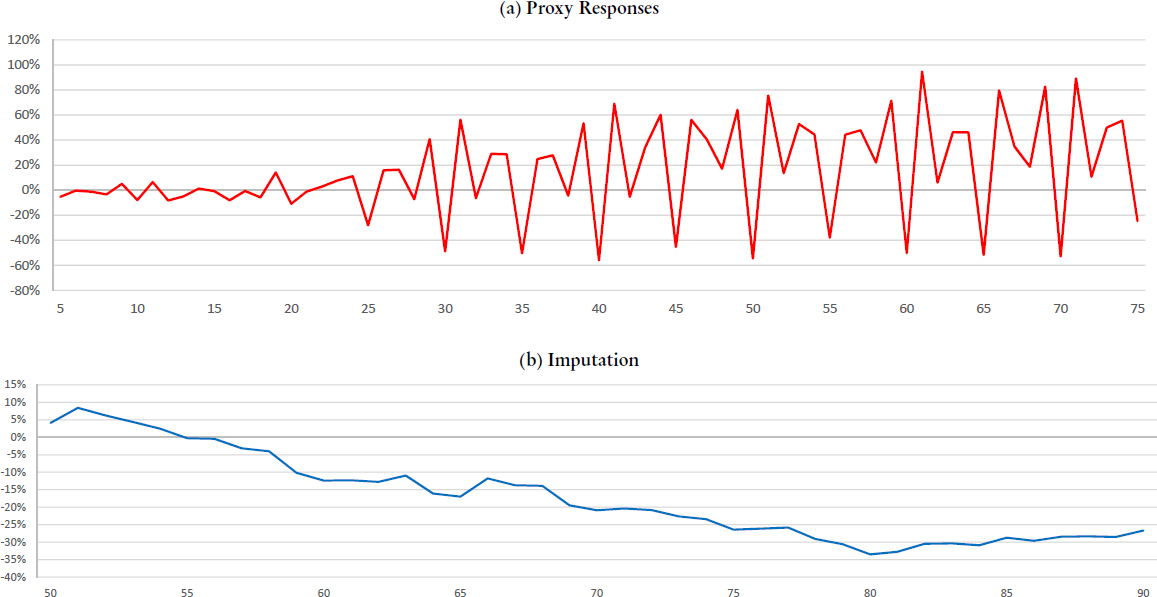

The research that Keller described was, effectively, reanalysis and simulation based on the 2010 census—directly substituting characteristics information from administrative records for cases that required imputation or that had been received by proxy (e.g., a neighbor or landlord). For substitution of race and Hispanic origin data, Keller said that the Bureau researchers weighed three different administrative records sources:

- Origin/country of birth information from the Census Numident file, mapping certain foreign nations of birth (as determined by work with the Census Bureau’s Population Division) to specific race and Hispanic origin values;9

- The Census Bureau’s internal Best Race and Hispanic Origin files, a research composite from various government and commercial sources that uses a rules-based approach to resolve unique race and Hispanic origin codes for person records where those values vary across different files; and

- Legacy 2000 census responses (2000 since this is simulating data in the 2010 census; 2010 census returns would be used in 2020 census processing data).

Age information for substitution comes from two of the same sources, Census Numident and reported responses in the 2000 census.

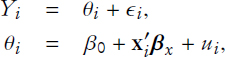

Keller said that his analysis leaves the 2010 census person count unchanged, but directly substitutes administrative records data for characteristics imputed in 2010 or filled by response from proxy reporters. This means that the analysis (and possible direct substitution) is only possible for 2010 census person records that both match to the administrative records sources and have characteristics values defined in those records—some 91 percent of persons in the 2010 census. The basic metric that Keller considered in this analysis is:

![]()

the basic percentage change in characteristic count when direct substitution is used relative to the imputation/proxy values used in actual 2010 census operations. He added the caveat that the effect of administrative records, demonstrated by this metric, is attenuated because of the relatively small size of the imputated-or-proxy-response universe, when analyzed over a total pool of 300 million persons. As a final caveat, Keller added that results could also differ if more or different alternative data sources were used rather than the limited set discussed here.

For Hispanic origin, Keller began by setting the context. The Census Coverage Measurement (CCM) program in the 2010 census estimated a 1.54 percent undercount of Hispanics nationally, about 776,000 persons. In the universe of 2010 census returns, 4.7 million values that had to be filled by imputation matched to the records sources (and have a valid value there); likewise, 6 million Hispanic origin responses gathered by proxy are eligible for

___________________

9 The distinction between Census Numident and the Social Security Administration Numerical Identification (SSA Numident) file is that the former is a reformatted version of the latter. SSA Numident is said to record all SSA transactions with regard to a specific Social Security number, while Census Numident reformats this information to construct a single record for every Social Security number.

substitution in this analysis. The two principal records sources both appear to show very good levels of agreement: Among 2010 census persons who self-reported a Hispanic origin, 98 percent of persons listed as being born in a primarily-Hispanic nation of birth in Census Numident (again, as determined with the Census Bureau’s Population Division) self-reported as Hispanic in the census. Likewise, person-record values from 2010 census self-reports of Hispanic origin and entries in the Bureau’s Best Hispanic Origin file agreed 96 percent of the time. Accordingly, for the simulation/analysis, Keller said that the Bureau team settled on a “hierarchy of use” for imputation and proxy response cases: directly substitute the Hispanic origin derived from Census Numident first; barring that, use the Best Hispanic Origin file; barring that, use the 2000 Census return.

Keller presented results for the 2010-imputed and 2010-proxy-reported groups, separately. For Hispanic origin, substituting administrative records values in lieu of imputed values yielded a 7.1 percent increase (on the order of 50,000 persons), while substitution increased Hispanic origin reporting 14.5 percent among proxy cases in the 2010 census (roughly 125,000 persons). Correspondingly, the measure of non-Hispanic origin dropped 1.2 percent and 2.5 percent using records in lieu of imputed and proxy-reported values, respectively.

Keller reported similar analysis paths for race and age: