3

Clinical Prevention Research Enterprise

The cornerstone of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendations is a review of research related to the preventive screenings and interventions assessed. As described in Chapter 2 and subsequently in Chapter 5, the USPSTF depends on the work of Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)-funded Evidence-based Practice Centers (EPCs) to identify, assess, and rate the quality of published research findings. This chapter reviews the important role the National Institutes of Health (NIH) serves in funding research relevant to the USPSTF, the contributions of other research funders, and the role of researchers.

NATIONAL INSTITUTES OF HEALTH

Organization and Funding Streams

NIH is an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH comprises 27 units, referred to as Institutes and Centers (IC). The Office of the Director sets policy for NIH and plans, manages, and coordinates the work of NIH ICs (NIH, 2021e). The Office of the Director program offices include the Offices of AIDS Research, Behavioral and Social Sciences Research, Disease Prevention, Strategic Coordination, Research on Women’s Health, among others. The NIH budget is substantial. Excluding supplemental appropriations for COVID-19 research, the total funding for NIH in fiscal year (FY) 2020 was more than $30 billion

(NIH, 2021e, n.d.-b). NIH supports extramural research, that is, research support to researchers outside the federal government, and intramural research, conducted by NIH employees. In addition, there are collaborative research teams consisting of intramural investigators and extramural researchers from multiple institutions and organizations.

NIH has a multi-layered process for developing its funding priorities (see Box 3-1). The most recent strategic plan identifies three objectives and five crosscutting themes for FY2021–2025 (see Box 3-2). NIH uses a variety of funding mechanisms to achieve its goals. The NIH website lists a total of 245 unique “activity codes” for grants; however, a small handful of these are commonly utilized and well known (NIH, n.d.-a). The R series is for investigator-initiated research projects and the RO1, for example, is the NIH standard independent research project grant mechanism. K awards are research career funding mechanisms. The P award series is for Research Program Projects and Centers. The U series supports cooperative agreements. See Table 3-1 for a description of the most common

mechanisms. NIH ICs might vary in which funding mechanisms they use or might have specialized eligibility criteria (NIH, 2019). NIH also issues contracts, which differ from research grants in significant ways, particularly with regard to NIH staff oversight (see Table 3-2).

All awards, whether for grants or contracts, undergo a review process. Most grant applications are subject to peer-review by “study sections.” The Center for Scientific Review at NIH reviews 75 percent of all applications to NIH (2021a). Study sections comprise non-NIH experts who serve as recurring or regular members in a particular domain, as well as ad hoc members. Study sections can be either Standing Study Sections or special emphasis panels targeting a specific request for applications. NIH staff experts manage study sections. Study sections evaluate the scientific and technical merit of the proposed research. Individual ICs use these reviews to decide which projects to fund (NIH, 2018b). A minority of applications receive funding. In FY2020, the total number of applications for research project grants and other mechanisms was 75,351. The number of awards was 17,087 for a 22.7 percent “overall success rate” (OER, 2020b). Success rates vary by funding mechanism and by IC. For example, the success rate for RO1s at the National Cancer Institute (NCI) was 12.3 percent but 30.8 percent for the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) PO1 awards.

TABLE 3-1 Frequently Used Funding Mechanisms at the National Institutes of Health

| R01 |

National Institutes of Health (NIH) Research Project Grant Program (R01)

|

| R41/R42 |

Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR)

|

| R43/R44 |

Small Business Innovative Research (SBIR)

|

| U01 |

Research Project Cooperative Agreement

|

| P01 |

Research Program Project Grant

|

| NIH Common Fund | The Common Fund has been used to support a series of short-term, exceptionally high impact, trans-NIH programs known collectively as the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. As the Common Fund grows and research opportunities and needs emerge in the scientific community, the portfolio of programs supported by the Common Fund will likely evolve to encompass a diverse set of trans-NIH programs, although the NIH Roadmap is likely to remain a central component. |

| The Other Transaction Authority allows the NIH director to enter into transactions (other than contracts, cooperative agreements, or grants) to carry out research pertaining to the Common Fund. “NIH would use the OTA when it needs greater flexibility to identify and engage nontraditional research partners, or to engage traditional partners in new ways, and negotiate terms and conditions that will concentrate their efforts, spur innovation, and facilitate collaborative problem solving.” Typical government procurement and grant laws, regulations, and policies do not apply to OT awards. |

SOURCES: Adapted from NIH, 2016b, 2019, n.d.-d.

TABLE 3-2 Comparison of Grants and Contracts

| Grant | Contract |

|---|---|

| Assistance mechanism to support research for the public good | Legally binding agreement to acquire goods or services for the direct use or benefit of the government |

| Peer review of broad criteria | Award based on peer review of stated evaluation factors, including technical criteria |

| Limited government oversight and control | More government oversight and control |

| Reports | Deliverables |

SOURCES: Adapted from NIH, 2016a; OER, 2020b.

An NIH summary of funding by grant mechanism from 2011 to 2020 (excluding supplemental COVID-19 appropriations) shows that in FY2019 the vast majority of funding went to research grants (49,092 awards totaling $28.1 billion average award of $573,276), whereas research and development contracts accounted for $1.7 billion (1,188 awards, average award $1,452,924) (OER, 2020a).

National Institutes of Health Solicitation of Research

NIH announces research funding opportunities through the following mechanisms: notice of special interest (NOSI), program announcement (PA), request for application (RFA), request for proposal (RFP), and parent announcements (NIH, 2021b,c, n.d.-c). PAs identify priority areas and usually specify a specific funding mechanism. One subtype, a PAS (a PA with set aside funds), includes funds set aside by an institute or center to fund applications that receive a score beyond the payline (funding cutoff points). Another subtype is known as a PAR, which is a PA whose applications will be reviewed by the funding institute, rather than NIH’s Center for Scientific Review. An RFA identifies a narrowly defined area for which one or more institutes has set aside funding for awarding grants (NIH, n.d.-c). RFPs are used to solicit contract proposals. Notices of special interest announce research priorities and direct applicants to PAs.

National Institutes of Health Spending on Prevention Research

In a recent perspective piece the director of the Office of Disease Prevention (ODP) wrote

Each NIH institute and center defines prevention to reflect its own mission. Even so, a general working definition for research at NIH is this: Prevention research encompasses both primary and secondary prevention. It includes research designed to promote health; to prevent onset of disease, disorders, conditions, or injuries; and to detect, and prevent the progression of, asymptomatic disease. Prevention research targets biology, individual behavior, factors in the social and physical environments, and health services, and informs and evaluates health-related policies and regulations. Prevention research includes studies for the identification and assessment of risk and protective factors; screening and identification of individuals and groups at risk; development and evaluation of interventions to reduce risk; translation, implementation, and dissemination of effective preventive interventions into practice; and development of methods to support prevention research. (Murray, 2017)

Using NIH’s Research Portfolio Online Reporting Tool the author noted an upward trend in the number of awards tagged as “prevention” and in the total dollars spent on prevention research between 2010 and 2016 (NIH, n.d.-e). The two ICs with the most money spent on prevention research were the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and NCI. Overall, more than 90 percent of 2016 prevention research was funded through the extramural research program, and approximately 14 percent was spent on clinical trials. The author noted challenges to

developing a robust prevention research portfolio at NIH, including low success rates, and it is difficult to document the long-term benefits of preventive interventions related to their harms and the number of intervention studies is limited (Murray, 2017). It should be noted that prevention research is a broader category than clinical prevention research and research of direct relevance to the USPSTF is an even more narrow set of research.

Funding of U.S. Preventive Services Task Force–Relevant Clinical Prevention Research

A recent analysis indicates that NIH is the largest single funder of the evidence cited in USPSTF reviews (Villani et al., 2018). The authors reviewed the funding sources for 1,650 articles included in support of 25 recommendations issued by the USPSTF over a 2-year period. Government agencies supported 56 percent of the studies, with nonprofit or university funding second at 32 percent, and industry sponsorship of 17 percent. Funding source was unknown for 21 percent of the studies. The numbers add up to more than 100 percent due to multiple funders for some research publications. NIH contributed funding to 25 percent of the articles, the largest funder identified in that review. A similar review of funding for publications used in support of the work of the Community Preventive Services Task Force, discussed in Chapter 2, showed that NIH was the leading sponsor for effectiveness research and economic reviews (Neilson et al., 2020).

NIH has made significant contributions in sponsoring clinical trials and other research showing the efficacy and effectiveness of clinical preventive interventions, leading to preventive services implemented in practice (Doria-Rose, 2021; Lauer, 2021). For example, the NCI-funded Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network, known as CISNET, provides modeling support to the USPSTF upon request. The Population-based Research to Optimize the Screening Process, known as PROSPR, focuses on underserved patient populations, information of great importance to prevention practitioners. The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) funded by NHLBI provided important information leading to updated blood pressure guidelines for clinical practice (NIH, n.d.-f).

As discussed in Chapter 2, all USPSTF recommendation statements include a section on research needs and gaps. This committee report was commissioned in part to help make the research needs more actionable. A major focus of the committee has been on those recommendation statements that have an I grade. ODP staff analyzed research that had been instrumental in upgrading an I statement to a letter grade recommenda-

tion (Klabunde, 2020; Klabunde et al., 2021). The authors examined 630 research publications cited in the evidence reviews for 14 recommendations that changed from I to a letter grade between 2010 and 2019. The analysis showed that 44 percent of the articles reported results from U.S.-supported studies; NIH provided support for 29 percent of all studies and 62 percent of U.S.-supported studies and was the largest single funder of articles. Thirteen of 27 ICs in NIH provided support. Additional analysis showed that for the NIH-supported studies determined to be “key” for closing nine evidence gaps, three used contract mechanisms, three used only R grants, and three used a combination of funding, including intramural research funding.

The Role of the Office of Disease Prevention

ODP sits in the Division of Program Coordination, Planning, and Strategic Initiatives in the Office of the Director (Murray, 2020). ODP does not have direct grant-making authority and therefore does not issue funding opportunity announcements (FOAs), with the exception of the Tobacco Regulatory Science Program (Klabunde et al., 2021). ODP Strategic Priorities are as follows:

- conduct portfolio analysis and impact assessment,

- identify research gaps,

- improve research methods,

- promote collaborative research,

- advance tobacco regulatory and prevention science, and

- communicate efforts and findings.

It has the following crosscutting themes:

- leading causes and risk factors for premature morbidity and mortality,

- health disparities, and

- dissemination and implementation research.

ODP is the NIH liaison to both the USPSTF and the CPSTF. ODP works with ICs to develop new activities to address gaps identified by both task forces. They use the following methods:

- soliciting IC task force liaisons

- soliciting IC nominations for new task force members

- soliciting IC input for task force topic choices and topic prioritization

- soliciting IC input on proposed task force research plans

- soliciting IC input on task force draft evidence reports and recommendations

- hosting conference calls with AHRQ staff and EPC representatives to discuss I statement research needs and gaps

- convening scientific meetings, workshops, and conferences

- issuing FOAs

- coordinating messaging across NIH for final task force recommendations

- soliciting IC participation in annual I statement survey

- disseminating reports from annual NIH I statement survey

ODP began surveying NIH ICs regarding the activities they have conducted related to I statements since 2015. The I statement survey provides ODP staff information to “identify and advance trans-NIH collaborations to address prevention research gaps.” The survey helps AHRQ “plan and prioritize USPSTF preventive services topics” and to demonstrate in its Annual Report to Congress the ways AHRQ and NIH work collaboratively to address critical research gaps in clinical prevention services. In 2015 all 42 current I statements were included in the survey. Beginning in 2018, ODP began collecting information about each I statement every other year on an alternating schedule. Relevant categories for activities include the following:

- active grants

- active contracts

- active Funding Opportunity Announcements

- intramural research projects

- meetings, workshops, and conferences

- publications with new evidence

- collaborations such as interagency agreements and committee or task force memberships

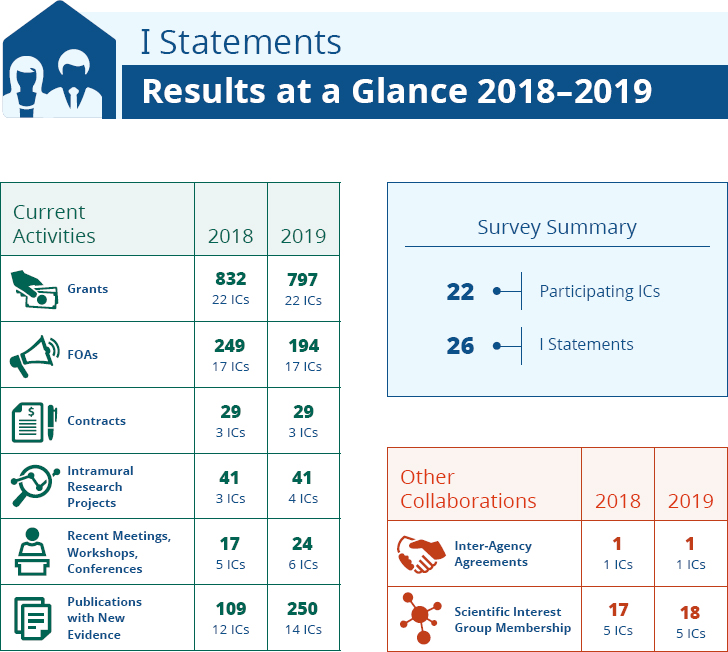

A summary of 2018–2019 current activities documented in the 2020 I statement survey is found in Figure 3-1 and Table 3-3.

For the 26 I statements included in the survey, 22 ICs report activities in 2018 and 2019. It is not obvious from the I statement surveys what proportion these activities represent compared to the totality of activities of each IC, however. In addition to the annual survey, ODP prepares “snapshot” documents for I statements. The I statement for Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults issued in 2020 contains the following research needs (USPSTF, 2020):

- More research is needed on the effect of screening and early detection of cognitive impairment (mild cognitive impairment [MCI] and mild to moderate dementia) on important patient, caregiver, and societal outcomes, including decision making, advance planning, and caregiver outcomes.

- The body of evidence on screening and interventions for cognitive impairment would benefit from more consistent definitions and reporting of outcomes to allow comparisons across trials, especially from trials with longer-term follow-up.

- Studies are needed of the effects of caregiver or patient–caregiver dyad interventions on delay or prevention of institutionalization, and the effects of delay in institutionalization on caregivers.

- Research is needed on treatments that clearly affect the long-term clinical course of cognitive impairment. It is also important that studies on screening and interventions for cognitive impairment report harms and reasons for attrition of trial participants.

NOTE: FOA = funding opportunity announcement; IC = institute and center.

SOURCE: ODP, 2020a.

TABLE 3-3 National Institutes of Health Activity Related to I Statements

| NIH Activity Type | I Statement Topic with the Most NIH-Reported Activity |

|---|---|

| Grants |

|

| Contracts |

|

| FOA |

|

| Intramural Research Project |

|

| Meetings, workshops, conferences |

|

| Reported publications with new evidence |

|

| Collaborations |

|

SOURCE: Adapted from ODP, 2020a.

The 2020 Snapshot for Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults indicated that 10 ICs reported at least one ongoing activity in 2018 and 2019 (ODP, 2020b). The National Institute on Aging reported the most activities in 2019, including 31 grants, 5 FOAs, 2 meetings/conferences, and 22 publications. Of the total active grants in 2019, 65 were research project grants (R01), 18 were other research grant (R) mechanisms, and 11 were center grants (program project/center [P], career development [K], and cooperative [U] grants). No contracts or intramural projects were identified.

A review of the listed RO1s suggests that research that was considered aligned with the I statement research needs ranges from “Olfactory Receptors for Semiochemical Detection in the Main Olfactory Epithelium” (3 RO1 DC014253-04) to “The UCSF Brain Health Assessment for the Detection of Cognitive Impairment Among Diverse Populations in Primary Care” (UG3NS105557) and “Understanding the Lived Experience of Couples Across the Trajectory of Dementia” (1RO1AG062684-01). Active FOAs range from “Health Disparities and Alzheimer’s Disease” (FOA number PAR-15-349) to “Novel Approaches to Diagnosing Alzheimer’s Disease and Predicting Progression” (PAR-15-359) and “Central Neu-

ral Mechanisms of Age-Related Hearing Loss” (RFA-AG-18-017). Many of the grants, contracts, FOAs, or publications in the Snapshot, while undoubtedly important, would not directly address the Research Needs and Gaps identified by the USPSTF in its 2020 Recommendation Statement. The committee hopes its taxonomy and the recommendations for its use, as described in Chapters 4 and 5, respectively, will offer a structured approach to categorizing research needs.

OTHER CLINICAL PREVENTION RESEARCH FUNDERS

While NIH is the single largest funder of biomedical research in the United States, other funders have an important role to play in clinical prevention research. These include the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD), voluntary health associations, health systems and payers, and the pharmaceutical and device industries.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

CDC has long played a prominent role in prevention of both acute and chronic diseases. CDC supports state and local health departments, conducts research, provides evidence-based advice on important issues, such as vaccination, trains early career clinicians in epidemiologic and outbreak investigations, conducts surveys (i.e., the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey), on important health topics, runs quarantine stations at ports of entry to the United States, and much more. As discussed in Chapter 2, CDC provides technical and administrative support to the Guide to Community Preventive Services (the Community Guide), a complementary effort to the USPSTF focusing on reviewing evidence for health promotion and disease prevention efforts directed at groups, communities, or other populations (Community Guide, n.d.). A review of the research included in 144 systematic reviews done for the CPSTF shows that while NIH was the leading sponsor of research used in both the effectiveness reviews and the economic reviews, CDC was the second leading sponsor of the research used by the CPSTF (Neilson et al., 2020). CDC was the third highest sponsor of research included in evidence reviews for the USPSTF.

CDC’s grant program consists of non-discretionary and discretionary grants, a competitive process. CDC’s cooperative agreements are used when it anticipates the need for significant agency involvement. In FY2020 CDC obligated $6.7 billion for non-COVID-19-related activities (CDC, n.d.). CDC funds the Prevention Research Centers (PRCs), teams

of academic researchers conducting applied public health prevention research (CDC, 2021). Some of this research is directly linked to topics of interest to the USPSTF but focused on ways to improve the use of preventive services. CDC-funded thematic research networks fund several PRCs to collaborate on a specific issue (CDC, 2020). The Cancer Prevention and Control Research Network includes eight PRCs that conduct research on the “the dissemination and implementation of evidence-based programs proven to increase cancer prevention and control. Members aim to increase the use of these programs among communities and public health partners.” (CDC, 2020) Other thematic networks of PRCs with interests complementary to the USPSTF are the Physical Activity Policy Research and Evaluation Network and the Nutrition and Obesity Policy Research and Evaluation Network.

Patient-Centered Outcomes and Research Institute

PCORI has the stated mission to fund “research that offers patients and caregivers the information they need to make important healthcare decisions” (PCORI, 2021a). PCORI’s National Priorities are under revision, but the proposed priorities are as follows (PCORI, 2021b):

- Increase Evidence for Existing Interventions and Emerging Innovations in Health

- Enhance Infrastructure to Accelerate Patient-Centered Outcomes Research

- Advance the Science of Dissemination, Implementation, and Health Communication

- Achieve Health Equity

- Accelerate Progress Toward an Integrated Learning Health System

PCORI’s FY2019 budget summary shows awards of $147 million for research, $29 million for dissemination and implementation, $25 million for engagement, and $7 million for research infrastructure (PCORI, 2019). PCORI has a program on evidence synthesis, which includes systematic reviews of comparative effectiveness research and other methodologic approaches. PCORI has developed a process by which it prioritizes research funding. The Science Oversight Committee and Advisory Panel uses five criteria (PCORI, 2015):

- Patient-Centeredness: Is the comparison relevant to patients, their caregivers, clinicians, or other key stakeholders and are the outcomes relevant to patients?

- Impact of the Condition on the Health of Individuals and Populations: Is the condition or disease associated with a significant burden in the U.S. population, in terms of disease prevalence, costs to society, loss of productivity, or individual suffering?

- Assessment of Current Options: Does the topic reflect an important evidence gap related to current options that is not being addressed by ongoing research?

- Likelihood of Implementation in Practice: Would new information generated by research be likely to have an impact in practice? (E.g., do one or more major stakeholder groups endorse the question?)

- Durability of Information: Would new information on this topic remain current for several years, or would it be rendered obsolete quickly by new technologies or subsequent studies?

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

The VA’s nationwide electronic health records lends itself to adhering to preventive interventions recommended by the USPSTF (Atkins, 2021). These 9 million records may be useful for addressing certain evidence gaps. In addition, the VA, where needed, will invest in large, definitive, national trials. For example, the CONFIRM study includes 50,000 veterans randomized to colonoscopy or to annual fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) who will be followed for 10 years to assess cancer incidence and mortality (VA, 2017). The PIVOT trial, a collaboration among the VA, NCI, and AHRQ, compared surgery versus watchful waiting for low-risk prostate cancer (Wilt, 2012). When considering priority gaps as a funder, the VA asks the following:

- Is it an important problem for their population?

- Is this an intervention they can deliver at scale if effective?

- Is the VA a logical place for a trial?

- Could VA population-based electronic health records data answer the question without a prospective randomized controlled trial? (Atkins, 2021).

U.S. Department of Defense

DOD was the second-largest federal sponsor of medical and health research and development in 2017, spending more than $2 billion (CRS, 2019; Research!America, 2018). Spending on health research at DOD goes through two distinct appropriations, the standard appropriations process and the Congressionally Directed Medical Research Program

(CDMRP) (Mendez, 2020). This funding is used only for medical research on topics identified by Congress. In FY2020 its budget was $1.4 billion and has accounted in recent years for at least half of the Defense Health Program’s Research, Development, Test, and Evaluation budget. Historically the largest research programs addressed breast cancer, prostate cancer, psychological health and traumatic brain injury, and two general programs for peer-reviewed medical research and peer-reviewed cancer research. In addition to the CDMRP priorities DOD health research includes the following focus areas: biomedical informatics and health information systems and technology, clinical and rehabilitative medicine, combat casualty care, medical chemical and biological defense, medical radiological defense, military infectious diseases, and military operational medicine (DOD, 2019). The single largest component of the Defense Health Program is TRICARE, the health care insurance program for more than 9 million service members, retirees, and beneficiaries (MHS, n.d.). Non-DOD researchers are subject to requirements for using the Military Health System data beyond the requirements for DOD investigators (OASDHA, 2012).

Health Systems

While the VA is among the largest health systems that sponsors research, many other health systems fund or host research. For example, the Health Care Systems Research Network includes 19 health systems with embedded research groups that are generally funded by a combination of internal and external sponsors (HCSRN, 2021; Rahm et al., 2019). Some systems, including Kaiser Permanente, HealthPartners, Inter-mountain Healthcare, and the Hospital Corporation of America, have invested substantial amounts of internal funding in applied research, which involves evaluating clinical or organizational practices that health systems can implement or encourage (Lieu and Platt, 2017).

Health systems also serve as environments for studies sponsored by NIH and other external funders that enable improved clinical decision making and identify care processes that improve safety, efficacy and effectiveness. For example, NIH has sponsored studies of how real-life factors, such as physician performance and patient adherence, influence the effectiveness of colonoscopy and fecal immunochemical testing in large-scale programs for colorectal cancer screening. NIH’s Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory is another large-scale effort that engages organizations including clinics and hospitals in pragmatic clinical trials, aiming to generate real-world evidence on benefits and risks of treatment options (NIH, 2018a). Whether funded internally or externally, research

on dissemination and implementation conducted in health systems can be directly applied to guide the development of real-world programs in clinical prevention.

Voluntary Health Associations

A recent analysis indicates that voluntary health organizations contribute less than 1 percent of all health research funds; however, those funds are far from trivial (Research!America, 2018). For example, in 2018 the American Cancer Society reported expenses of almost $148 million toward cancer research, second only to NIH (ACA, 2019; McKenzie et al., 2018). In 2019 the American Diabetes Association reported spending almost $37 million for research (ADA, 2019). A particularly important type of research funded by these types of organizations is for implementation of research findings, although they do provide support for clinical trials. Another major contribution of voluntary health agencies is their advocacy for funding for research (McKenzie et al., 2018).

Private Industry

Private industry funds a significant amount of biomedical research in the United States. The analysis of who funds the research cited in USPSTF systematic reviews indicated that 17 percent of articles were funded in full or in part by industry (Villani et al., 2018). Of the recommendation topics reviewed, screening for chlamydia and gonorrhea had the highest proportion of papers funded by industry (75 percent). Several of the preventive interventions are either directly of relevance to the pharmaceutical industry (preventive medications) or indirectly (screening for a condition whose treatment involves a pharmaceutical or device); thus industry is an obvious partner in evidence generation for USPSTF use.

International Sources of Funding

As described earlier, research into the source of funding for research articles included in the systematic reviews used by the USPSTF indicates that NIH is the largest government contributor (420 articles). However, the USPSTF does not restrict itself to research funded by or conducted in the United States. The United Kingdom provided funding for 84 articles, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia supported research in 37 articles, and the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development supported research in 35 articles (Villani et al., 2018).

RESEARCHERS

Generating a body of evidence aimed toward addressing an evidence gap often requires research that spans multiple disciplines and areas of expertise. For example, clinical experts are needed specific to adult or pediatric patients, and within these broad categories, to address specific subspecialties (e.g., cardiology, cancer, mental health). In addition, expertise may be needed in health services research, biostatistics, modeling, clinical trial design, and economics. Such a team may require multiple institutions to include the researchers best equipped to design and conduct a study that generates the needed evidence.

The inclusion of multiple institutions may also be needed to address evidence gaps in specific populations, such as racial/ethnic minorities and/or persons at high risk for the condition. The inclusion of these groups reduces health inequities and improves the generalizability of the generated evidence. Moreover, studies conducted at multiple institutions in different settings provide important context about how clinical prevention services manifest in academic medical centers, in community settings (including safety net settings), and in different health care delivery organizations, such as integrated health care systems. Researchers need to have the flexibility to convene such teams and may even be encouraged to do so. NIH has a track record of incentivizing teams such as CISNET and the former Cancer Research Network for the purpose of generating evidence within or across specific research settings. An advantage of these collaborative research arrangements is the investment in infrastructure and expertise that may facilitate future research in a more expedient, nimble manner.

Researchers can play an important role in drafting and reviewing funding announcements through their participation on NIH advisory panels (e.g., NCI convenes a panel of researchers to identify provocative questions and also has a Board of Scientific Advisors). A collaborative relationship between the research community and funders can help to ensure that submitted applications meet the intent of the research call. This exchange will also inform funders about the time required to respond to such calls for applications so that multi-institutional and multidisciplinary groups can contractually come together and meet regulatory requirements, such as an institutional review board review.

REFERENCES

ACA (American Cancer Society). 2019. 2018 Annual Report. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/online-documents/en/pdf/reports/2018-annual-report.pdf (accessed November 2, 2021).

ADA (American Diabetes Association). 2019. 2019 Annual Report. Arlington, VA: American Diabetes Association. https://www.diabetes.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/ADA-2019-AnnualReport.pdf (accessed November 2, 2021).

Atkins, D. 2021. Funder perspectives on addressing evidence gaps. Presented on March 16, 2021, at Meeting 4 of the Committee on Addressing Evidence Gaps in Clinical Prevention. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/03-16-2021/addressing-evidence-gaps-in-clinical-prevention-committee-meeting-session-2 (accessed November 2, 2021).

CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). 2020. Thematic research networks. https://www.cdc.gov/prc/thematic-networks.htm (accessed August 30, 2021).

CDC. 2021. Prevention research centers. https://www.cdc.gov/prc/index.htm (accessed August 30, 2021).

CDC. n.d. Office of the Financial Resources (OFR) FY-2020 assistance snapshot at CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/funding/documents/fy2020/fy-2020-ofr-assistance-snapshot-508.pdf (accessed August 30, 2021).

Community Guide. n.d. About the Community Guide. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/about/about-community-guide (accessed August 30, 2021).

CRS (Congressional Research Service). 2019. FY-2020 budget request for the Military Health System. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/IF11206.pdf (accessed August 30, 2021).

DOD (U.S. Department of Defense). 2019. Department of Defense strategic medical research plan response to Section 736 of the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2019 (Public Law 115-232). https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Congressional-Testimonies/2019/04/08/Strategic-Medical-Research-Plan (accessed August 31, 2021).

Doria-Rose, V. P. 2021. Pathways to understanding evidence gaps: Funders’ perspective. Presented on March 4, 2021, at Meeting 4 of the Committee on Addressing Evidence Gaps in Clinical Prevention. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/03-04-2021/addressing-evidence-gaps-in-clinical-prevention-committee-meeting-4-session-1 (accessed October 26, 2021).

HCSRN (Health Care Systems Research Network). 2021. Health care systems research network: Membership. https://www.hcsrn.org/en/About/Membership (accessed August 30, 2021).

Klabunde, C. N. 2020. Engaging NIH and extramural investigators in addressing evidence gaps in clinical prevention. Presented on December 15, 2020, at Meeting 1 of the Committee on Addressing Evidence Gaps in Clinical Prevention. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/12-15-2020/addressing-evidence-gaps-in-clinical-prevention-committee-meeting-1-session-2 (accessed November 2, 2021).

Klabunde, C. N., E. M. Ellis, J. Villani, E. Neilson, K. Schwartz, E. A. Vogt, and Q. Ngo-Metzger. 2021. Characteristics of scientific evidence informing changed U.S. Preventive Services Task Force insufficient evidence statements. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0749379721004578 (accessed November 29, 2021).

Lauer, M. 2021. Perspectives on addressing evidence gaps: NIH. Presented on March 16, 2021, at Meeting 4 of the Committee on Addressing Evidence Gaps in Clinical Prevention. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/03-16-2021/addressing-evidence-gaps-in-clinical-prevention-committee-meeting-session-2 (accessed October 26, 2021).

Lieu, T. A., and R. Platt. 2017. Applied research and development in health care—Time for a frameshift. New England Journal of Medicine 376(8):710–713. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejmp1611611 (accessed November 2, 2021).

McKenzie, J. F., R. R. Pinger, and D. Seabert. 2018. Organizations that help shape community and public health. In An introduction to community & public health. 9th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Mendez, B. H. P. 2020. Congressionally directed medical research programs: Background and issues for Congress. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. https://www.everycrsreport.com/files/2020-11-10_R46599_76afd8a7d9eef054e19c53392f97485ff7b3037e.pdf (accessed November 2, 2021).

MHS (Military Health System). n.d. Patients by beneficiary category. https://www.health.mil/I-Am-A/Media/Media-Center/Patient-Population-Statistics/Patients-by-Beneficiary-Category (accessed August 30).

Murray, D. M. 2017. Prevention research at the National Institutes of Health. Public Health Reports 132(5):535–538.

Murray, D. 2020. Closing evidence gaps in clinical prevention: A perspective from the NIH. Presented on December 15, 2020, at Meeting 1 of the Committee on Addressing Evidence Gaps in Clinical Prevention. https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/12-15-2020/addressing-evidence-gaps-in-clinical-prevention-committee-meeting-1-session-2 (accessed November 2, 2021).

Neilson, E., J. Villani, S. L. Mercer, D. L. Tilley, I. Vincent, A. Alston, and C. N. Klabunde. 2020. Sources of support for studies that inform recommendations of the Community Preventive Services Task Force. Public Health Reports 135(6):813–822.

NIH (National Institutes of Health). 2016a. Contracts. https://grants.nih.gov/funding/contracts.htm (accessed November 2, 2021).

NIH. 2016b. Frequently asked questions for other transaction awards. All of Us Research Program. https://www.nih.gov/allofus-research-program/frequently-asked-questions-other-transaction-awards (accessed November 2, 2021).

NIH. 2018a. HCS research collaboratory—Demonstration projects for pragmatic clinical trials (ug3/uh3) rfa-rm-16-019. https://commonfund.nih.gov/hcscollaboratory/fundedresearch (accessed August 30, 2021).

NIH. 2018b. NIH research planning. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/nih-research-planning (accessed August 11, 2021).

NIH. 2019. Types of grant programs. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/funding_program.htm (accessed August 11, 2021).

NIH. 2021a. About CSR. https://public.csr.nih.gov/AboutCSR (accessed August 11, 2021).

NIH. 2021b. Funding types: Know the differences. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Funding/About-Funding/Funding-Types-Know-Differences (accessed August 30, 2021).

NIH. 2021c. NIH guide for grants and contracts. https://grants.nih.gov/funding/search-guide/index.html (accessed August 30, 2021).

NIH. 2021d. NIH-wide strategic plan. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/nih-wide-strategic-plan (accessed November 2, 2021).

NIH. 2021e. Who we are. https://www.nih.gov/about-nih/who-we-are/organization (accessed August 10, 2021).

NIH. n.d.-a. Activity codes search results. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/funding/ac_search_results.htm (accessed August 10, 2021).

NIH. n.d.-b. Budget and spending. https://report.nih.gov/funding/nih-budget-and-spending-data-past-fiscal-years/budget-and-spending (accessed August 10, 2021).

NIH. n.d.-c. Description of the NIH guide for grants and contracts. https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/description.htm (accessed August 30, 2021).

NIH. n.d.-d. NIH Common Fund and other transaction authority. https://dpcpsi.nih.gov/sites/default/files/OTA_slide_508.pdf (accessed November 2, 2021).

NIH. n.d.-e. RePORTER. https://report.nih.gov (accessed August 11, 2021).

NIH. n.d.-f. Systolic blood pressure intervention trial (SPRINT) study. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/science/systolic-blood-pressure-intervention-trial-sprint-study (accessed October 26, 2021).

OASDHA (Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Health Affairs). 2012. Guide for DOD researchers on MHS data. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Defense. https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Publications/2012/10/10/Guide-for-DoD-Researchers-on-Using-MHS-Data (accessed November 2, 2021).

ODP (Office of Disease Prevention). 2020a. NIH activities related to “insufficient evidence” statements of the US Preventive Services Task Force: Results from the 2020 annual survey of institutes, centers, and offices. Attachment from personal correspondence with Carrie Klabunde, AHRQ staff member, January 7, 2021. Available by request from the project Public Access File at https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/ManageRequest.aspx?key=51932 (accessed November 3, 2021).

ODP. 2020b. Snapshot of I statement survey results: Cognitive impairment in older adults: Screening. Attachment from personal correspondence with Carrie Klabunde, AHRQ staff member, January 8, 2021. Available by request from the project Public Access File at https://www8.nationalacademies.org/pa/ManageRequest.aspx?key=51932 (accessed November 3, 2021).

OER (Office of Extramural Research). 2020a. NIH research grants and other mechanisms including research and development contracts. https://report.nih.gov/funding/nih-budget-and-spending-data-past-fiscal-years/budget-and-spending (accessed November 2, 2021).

OER. 2020b. Research project grants (RPGs) and other mechanisms. Table #205C. https://report.nih.gov/funding/nih-budget-and-spending-data-past-fiscal-years/success-rates (accessed November 2, 2021).

PCORI (Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute). 2015. Generation and prioritization of topics for funding announcements. https://www.pcori.org/research-results/how-we-select-research-topics/generation-and-prioritization-topics-funding-4 (accessed August 30, 2021).

PCORI. 2019. PCORI 2019 report. Washington, DC: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Insitute. https://www.pcori.org/2019-annual-report (accessed November 2, 2021).

PCORI. 2021a. Our programs. https://www.pcori.org/about-us/our-programs (accessed August 11, 2021).

PCORI. 2021b. PCORI’s proposed national priorities for health: An ambitious vision for the years ahead. https://www.pcori.org/blog/proposed-national-priorities-for-health-an-ambitious-vision-for-the-years-ahead (accessed August 30, 2021).

Rahm, A. K., I. Ladd, A. N. Burnett-Hartman, M. M. Epstein, J. T. Lowery, C. Y. Lu, P. A. Pawloski, R. N. Sharaf, S. Y. Liang, and J. E. Hunter. 2019. The Healthcare Systems Research Network (HCSRN) as an environment for dissemination and implementation research: A case study of developing a multi-site research study in precision medicine. eGEMs 7(1):16.

Research!America. 2018. U.S. investments in medical and health research and development 2013–2017. https://www.researchamerica.org/sites/default/files/Policy_Advocacy/2013-2017InvestmentReportFall2018.pdf (accessed August 30, 2021).

USPSTF (U.S. Preventive Services Task Force). 2020. Cognitive impairment in older adults: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/cognitive-impairment-in-older-adults-screening (accessed August 17, 2021).

VA (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs). 2017. Largest-ever VA clinical trial enrolls 50,000th veteran. https://www.research.va.gov/currents/1117-Largest-ever-VA-clinical-trial.cfm (accessed November 2, 2021).

Villani, J., Q. Ngo-Metzger, I. S. Vincent, and C. N. Klabunde. 2018. Sources of funding for research in evidence reviews that inform recommendations of the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 319(20):2132–2133.

Wilt, T. J. 2012. The prostate cancer intervention versus observation trial: VA/NCI/AHRQ cooperative studies program #407 (PIVOT): Design and baseline results of a randomized controlled trial comparing radical prostatectomy with watchful waiting for men with clinically localized prostate cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute Monographs 2012(45):184–190.