Proceedings of a Workshop

WORKSHOP OVERVIEW1

Cancer treatment can cause an array of significant short- and long-term physical, psychosocial, and socioeconomic consequences for patients and their families. Examples of adverse effects that individuals may experience include the development of life-threatening medical conditions, disability, sexual dysfunction, fatigue, depression, and financial distress including job loss. To examine opportunities to prevent and mitigate the adverse effects of cancer treatment, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies) convened the virtual workshop, Addressing the Adverse Consequences of Cancer Treatment, on November 9 and 10, 2020. This workshop was hosted by the National Cancer Policy Forum (NCPF) in collaboration with the Forum on Aging, Disability, and Independence. It assembled a broad range of experts including clinicians, researchers, patients, and patient advocates, as well as representatives of health care organizations, academic medical centers, insurers, and government agencies, to examine the short- and long-term adverse effects that patients may experience as a result of cancer treatment and to consider opportunities to improve quality of life for

___________________

1 The planning committee’s role was limited to planning the workshop, and the Proceedings of a Workshop was prepared by the workshop rapporteurs as a factual summary of what occurred at the workshop. Statements, recommendations, and opinions expressed are those of the individual presenters and participants and are not necessarily endorsed or verified by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, and they should not be construed as reflecting any group consensus.

cancer survivors and their families. Workshop presentations and discussions focused on topics that included

- An overview of the array of adverse consequences of cancer treatment across the life course, including physical, psychosocial, and socioeconomic consequences;

- Opportunities to improve informed and goal-concordant care, especially in light of evidence gaps on the long-term consequences of cancer treatment;

- Opportunities to redesign cancer treatment to screen for and reduce toxicities;

- Ways to improve the evidence base for addressing the adverse consequences of cancer treatment; and

- System-level redesign and policy changes to improve survivorship care.

This proceedings summarizes the presentations and discussions at the workshop. Suggestions from individual participants are presented in Box 1 and in the proceedings. The workshop Statement of Task is provided in Appendix A and the workshop agenda is in Appendix B. Speaker presentations and the webcast have been archived online.2

THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE OF CANCER CARE AND SURVIVORSHIP

Advances in oncology care have led to an increasing number of cancer survivors. Cathy Bradley, professor and deputy director at the University of Colorado Comprehensive Cancer Center, and David Cella, professor and chair of the Department of Medical Social Sciences in the Feinberg School of Medicine at Northwestern University, said that the number of cancer survivors in the United States is estimated to increase from approximately 17 million now to more than 20 million by 2030 (ACS, 2020, 2021; NCI, 2020). Several speakers—including Julie Bynum, professor of medicine at the University of Michigan; Ashley Leak Bryant, associate professor from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; and Christopher Flowers, chair and professor in the Department of Lymphoma/Myeloma at the MD Anderson Cancer Center—emphasized that as people are living longer after a cancer diagnosis, the future of oncology care needs to shift toward reducing both disability and the occurrence of secondary cancers and other debilitating consequences of cancer treatment.

___________________

2 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/11-09-2020/addressing-the-adverse-consequences-of-cancer-treatment-a-workshop (accessed June 15, 2021).

Gwen Darien, executive vice president at the National Patient Advocate Foundation, noted that in the recent past, cancer care focused primarily on completion of treatment. Wendy Harpham, physician, author, and columnist for Oncology Times, added that as both a cancer survivor and doctor, she feels that addressing the adverse effects of cancer treatment is as important as pursuing more effective cancer therapies (for more patient perspectives, see Box 2). Bradley said that extending the length of survivorship brings hope, but it is also important to address how treatments affect the emotional, psychological, and economic aspects of cancer survivors’ lives.

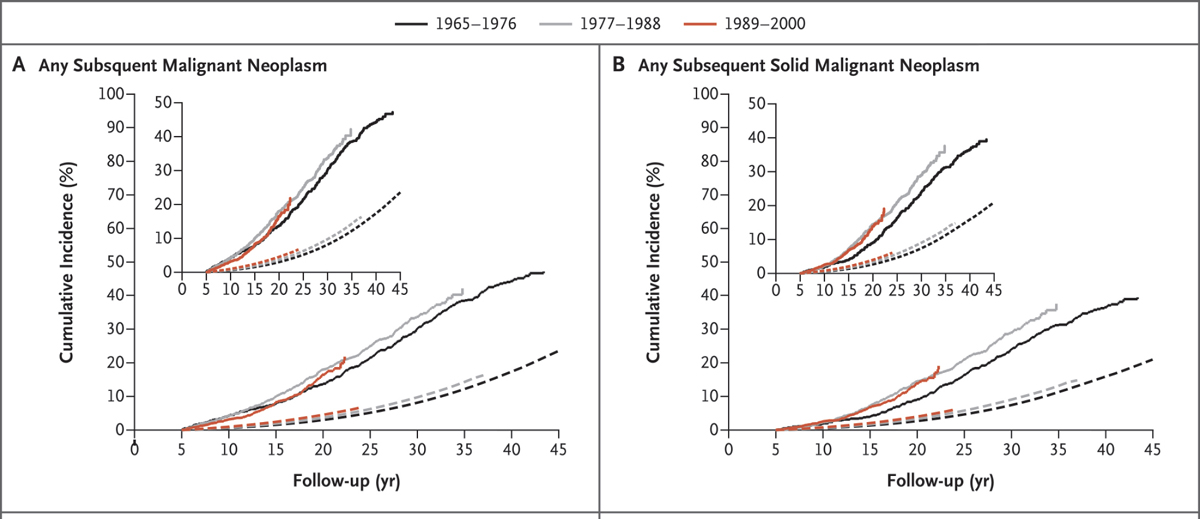

Several speakers discussed the delicate balance between treatments that may extend lives but that may also reduce quality of life. Lawrence Shulman, professor of medicine from the University of Pennsylvania, said that some of the adverse consequences of cancer treatment have increased the risk of second cancers and other treatment-related medical complications among cancer survivors (see Figure 1). He cited one study that compared the risk of developing a second cancer among patients who have received treatment for Hodgkin’s

lymphoma versus that in the general public. The study reported that survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma were at an increased risk of developing subsequent malignant neoplasms decades after therapy, probably due to radiation exposure during treatment (Schaapveld et al., 2015).

Survivors of Pediatric Cancers

Each year, about 10,000 children under the age of 15 are diagnosed with cancer (NCI, 2018). Leslie Robison, associate director of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, noted that 85 percent of children treated with cancer will now survive 5 years or more (ACS, 2021). This translates into more than 500,000 survivors of childhood cancer in the United States. Robison and several other speakers—including Smita Bhatia, professor and vice chair of the Department of Pediatrics at The University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, and Shannon MacDonald, associate professor at Harvard

Medical School and member of the Department of Radiation Oncology at Massachusetts General Hospital—discussed the effects of cancer treatment on survivors of pediatric cancer. MacDonald said that the majority of patients with pediatric cancers will survive their cancers, but will have a very high risk of developing a variety of life-threatening illnesses, either soon after their

diagnosis or much later in their adult lives due to the late effects of their cancer treatments (Bhakta et al., 2016; Hudson et al., 2013). Bhatia said that more than 40 percent of pediatric cancer survivors develop a severe or life-threatening chronic health condition within 30 years of diagnosis (Oeffinger et al., 2006). Robison noted that overall, childhood cancer survivors have

NOTES: Solid lines represent the observed incidence and dashed lines the expected incidence in the general population. The smaller inset graphs show the same data on an enlarged y-axis (vertical). The different colors represent the time periods when the patients were treated.

SOURCES: Shulman presentation, November 9, 2020; Schaapveld et al. 2015.

about a five- to six-fold increased risk of developing a secondary cancer. He said that some of that increased risk is due to individuals’ underlying genetic predispositions to developing certain cancers (Ehrhardt et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2018).

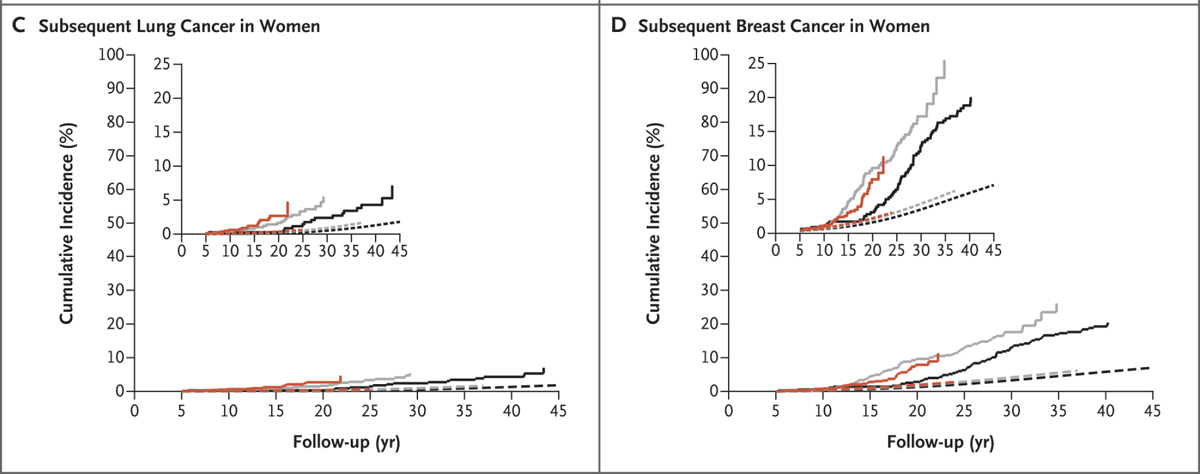

Robison explained that survivors of pediatric cancers are at risk for a broad spectrum of concomitant morbidities affecting their physical and mental development, including impairment of organ function and fertility and reproduction, and they may suffer from chronic psychosocial distress that can affect their quality of life (Robison and Hudson, 2014). Similarly, endocrine abnormalities are common among childhood cancer survivors, Robison added. Survivors of pediatric cancers also experience premature aging and frailty (Ness et al., 2013; Qin et al., 2020; Song et al., 2020), and are more likely to suffer financial and psychological hardships at a younger age compared to those who have not been diagnosed with cancer (Huang et al., 2019) (see Figure 2). Robison stressed that while the incidence of serious chronic conditions among childhood cancer survivors has decreased since the 1970s, it is still higher than what is seen in the general population (Armstrong et al., 2016; Gibson et al., 2018).

SOURCES: Robison presentation, November 9, 2020; Robison and Hudson, 2014 (updated version of the figure that was presented at the workshop).

Survivors of Adolescent and Young Adult Cancers

The National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program3 defines adolescents and young adults (AYAs) as those diagnosed with cancer between 15 to 39 years of age. K. Scott Baker, professor and director of the Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Program and the Cancer Survivorship Program at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine, agreed with other speakers that many AYA treated for cancer experience long-term adverse effects as a result of their treatments. Baker noted that some cancers and their treatments can alter body image, disrupt sexuality, and cause infertility, adding additional stressors for the survivor. He stressed that AYA are prone to developing anxiety, depression, and a fear of cancer recurrence (Park and Rosenstein, 2015; Quinn et al., 2015).

Older Adult Survivors of Cancer

Supriya Gupta Mohile, professor of medicine and surgery and director of the Geriatric Oncology Research Group at the University of Rochester Medical Center, discussed the effects of cancer treatment on older adult cancer survivors. Mohile said that older adults are the largest demographic diagnosed with cancer,4 and the number of survivors who are 75 or older will continue to increase. Mohile said that one of the challenges many older adults face is a lack of age-appropriate cancer care, noting that oncology clinicians have little training in geriatrics, and there is often inadequate care coordination and lack of support for caregivers of older adults (IOM, 2013). She added that older adults are often underrepresented in clinical trials, which makes evidence-based treatment decision making for that population challenging.

Mohile emphasized that older adults have unique social needs, which are often not addressed in standard oncology care. She said one analysis reported that about two-thirds of older adults have at least one social support need (emotional, physical, practical, or informational). Of those, 45 percent had at least one unmet social need. Patients who were non-white, not married, or who had a high symptom burden were at the greatest risk of having multiple unmet social support needs (Williams et al., 2019). Mohile described an analysis that used cross-sectional data from the 2003 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey to examine whether cancer was independently associated with vulnerability and frailty. The analysis found that functional impairments, geriatric

___________________

3 See https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/aya.html (accessed August 12, 2021).

4 See https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/age (accessed August 12, 2021).

syndromes, vulnerability, and frailty were more prevalent in cancer survivors compared to people of the same age without a cancer diagnosis (Mohile et al., 2009). Further research is needed to determine whether the higher prevalence of symptoms was due to cancer, its treatment, or both, Mohile noted. Another recent NCPF workshop focused on the unique challenges of treating older adults with cancer (NASEM, 2021).

Psychological Effects of Cancer Treatment on Patients and Caregivers

Many speakers reported on the increasing awareness of the effects of cancer treatment on patient and caregiver mental health. Cleo Samuel-Ryals, associate professor and health science researcher at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said the psychosocial effects are just as serious as the physical effects of cancer treatment. Harpham and Cella emphasized that the distress associated with coping with the adverse effects of cancer treatments adds to the difficulty cancer survivors face. These psychological complications often interfere with treatment adherence, add to the overall symptom burden of patients, and reduce patient satisfaction with their care, Cella added.

Kathlyn Conway, cancer survivor, author, and psychotherapist at the Women’s Therapy Center Institute, discussed the depression she experienced after her diagnosis and during her cancer treatment. “Emotional pain is often not validated, and instead, our culture values optimism and thinking positively. Additionally, the insistence on positive thinking, while seemingly harmless, may reflect a general inability as a culture to deal with loss, pain, and grief,” Conway said. She noted that people with cancer do not want to be labeled as bad patients, so they can be reluctant to discuss their coping skills with their care team. Clinicians, in turn, may fear that their patient’s emotions will be overwhelming or require too much time and attention, she added, so conversations about mental health are often avoided. Conway and Cella stressed that psychological symptoms of cancer survivors are often under-detected by clinicians.

Conway and Cella said another side effect of cancer treatment that is underrecognized is the psychological toll it takes on caregivers for patients with cancer. A meta-analysis of 30 studies with a total of 21,149 cancer caregivers demonstrated that nearly half of all cancer caregivers experience depression and anxiety (Geng et al., 2018).

Financial Effects

Many cancer survivors experience financial hardships. Robin Yabroff, scientific vice president of health services research at the American Cancer Society (ACS), noted that increasing treatment intensity and costs, patient cost

sharing with high deductible health insurance plans, and lack of insurance are some of the causes of the increased financial burden of cancer. Yabroff stressed that the financial burden is compounded by the fact that the cost of new cancer drugs has increased exponentially since the 1970s, unlike the median household income, which has remained fairly flat (Prasad et al., 2017).

She said that compared to adults without a cancer history, cancer survivors are more likely to report higher out-of-pocket costs, more likely to file for bankruptcy protection, have higher levels of distress about the ability to pay medical bills, delay or forgo medical care because of cost, and worry about daily financial needs including food and housing (Han et al., 2020b; Yabroff et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2019). She added that the term “financial toxicity” has been used to describe problems a patient has related to the cost of medical care including debt and bankruptcy, as well as reduced quality of life and access to medical care (Lathan et al., 2016; Ramsey et al., 2016; Yabroff et al., 2020; Zafar et al., 2015).

Yusaf Zafar, associate professor of medicine, public policy, and population science at Duke University and chief quality and innovation officer at the Duke Cancer Institute, shared the example of one of his patients who was diagnosed with localized rectal cancer when he was in his 30s. Although the patient had employer-sponsored health insurance, he did not have prescription drug coverage. Consequently, his out-of-pocket costs for his oral chemotherapy led to nearly $4,000 of medical debt in just 5.5 weeks.

Zafar also said that health insurance does not cover indirect costs of cancer care, such as childcare; transportation to and from a cancer treatment center; lost work and lost income during treatment and possible resulting sick days; and the cost of legal services, medical supplies, and specialized diets. Mary (Dicey) Jackson Scroggins, director of global outreach and engagement at the International Gynecologic Cancer Society and founding partner of Pinkie Hugs, LLC, and Candace Henley, chief executive officer of The Blue Hat Foundation emphasized the financial toll that cancer had on them, and on their families. Henley noted that patients are often unprepared for the financial hardship associated with cancer. She said for example she lost income when she was unable to work after her cancer treatment. Also, she lost her 401(k) trying to protect her home.

Health Inequities

Health inequities adversely affect groups of people who have systematically experienced greater obstacles to health based on their racial or ethnic group, religion, socioeconomic status, gender, age, mental or physical disability, sexual orientation, geographic location, or other characteristics historically linked to discrimination or exclusion (CDC, 2020). Samuel-Ryals said

that health inequities are established through structural racism and bias. She defined structural racism as racial differences in access to goods, services, and opportunities that are codified in societal institutions of custom, practice, and law. Structural racism is perpetuated both by action and inaction that maintains the status quo (Jones, 2000). Samuel-Ryals stressed that health inequities can be modified through systemic change. Structural inequities, such as limited access to healthy food, clean air, safe housing, jobs, and education are a predictor of poor physical and mental health.5

Samuel-Ryals applied Camara Phyllis Jones’s framework6 for understanding racism to describe the existing inequities in cancer care. She explained that at the interpersonal level, the clinician or members of the care team may make assumptions about a patient based on their race or ethnicity. When acted on, these assumptions are called implicit bias, which are unconscious attitudes, beliefs, or prejudices that people hold. Samuel-Ryals said that a clinician’s unconscious bias can be manifested in limiting cancer patients’ access or referrals to supportive care services. She said that while clinicians may acknowledge that disparities exist on a broader scale, they may be less inclined to recognize the role that clinicians play in maintaining or perpetuating these disparities within their own practice and with the patients that they treat (Sequist et al., 2008). She stressed that the lack of institutional awareness of health equity within hospitals and universities, and therefore a lack of commitment to create and nurture a more equitable environment can further perpetuate inequities.

Samuel-Ryals noted that racial and ethnic minorities experience substantial psychosocial and socioeconomic burden both during and after cancer treatment. She said several studies have reported that racial and ethnic minorities who have cancer are more likely to report worse physical and functional well-being, higher levels of posttraumatic distress, greater financial burden, and job disruptions as well as higher rates of infertility and sexual dysfunction (Letourneau et al., 2012; Samuel et al., 2016, 2020a,b; Vin-Raviv et al., 2013). An October 2021 workshop hosted by NCPF will focus on ways to reduce health disparities and promote health equity in cancer care and patient outcomes.7

Ashley Leak Bryant, associate professor in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Nursing, added that there are number of

___________________

5 See https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health (accessed August 12, 2021).

6 For more on the theoretic framework for understanding racism on three levels: institutionalized, personally mediated, and internalized, see https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/practice/resources/equitylibrary/docs/jones-allegories.pdf (accessed August 12, 2021).

7 See https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/10-25-2021/promoting-health-equity-in-cancer-care-a-virtual-workshop (accessed October 28, 2021).

social determinants of health that cause health inequities. For example, where patients live can affect their access to safe housing, parks and other green spaces, sidewalks, bike lanes, and inexpensive grocery stores selling fresh food, which can influence health outcomes. In addition, patients with limited health literacy and patients with limited English proficiency may have more difficulty in understanding the adverse effects and consequences of their cancer, Bryant noted. She added that there can also be inequities in patients’ access to technology and in their digital literacy.

CHALLENGES TO ADDRESSING ADVERSE CONSEQUENCES OF CANCER TREATMENT

Participants at the workshop noted several challenges in addressing the adverse consequences of cancer treatment, including the variability in patients’ responses to treatment (which conflicts with the push for standardization), a lack of mental health care providers, lack of reimbursement for psychosocial care, and time constraints on clinicians.

Diversity of Patient Experiences Across the Cancer Care Continuum

Several participants discussed the varying experiences of patients and survivors across the cancer care continuum. Henley said that “there is not a one-size-fits-all survivorship.” Meg Gaines, Distinguished Emerita Clinical Professor of Law and director emerita at the Center for Patient Partnerships of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, noted that the diversity in patient responses to treatment is contrary to the call to standardize clinical care and quality metrics. Several speakers stressed that each survivor is unique, hence the need for personalized care.

Lack of Access to Psychosocial Services

There is an imbalance between supply and demand for psychosocial services and supports for patients and survivors of cancer, said Howard Burris, president and chief medical officer and executive director of drug development at the Sarah Cannon Research Center. He added that there is a need for patients with cancer to be part of a community outside of the clinic so that they can lean on someone for support, particularly in the absence of professional help. Catherine Alfano, vice president of cancer care management and research at Northwell Health Cancer Institute, agreed that the lack of behavioral health professionals increases the need for patients to learn and engage in appropriate self-management techniques. Alfano stressed that despite the

significant need that patients with cancer have for mental health care, currently, mental health is not considered to be as important as other aspects of a patient’s care. That value judgment affects the reimbursement for such care, she noted. Cella mentioned that behavioral health reimbursement has always lagged behind other reimbursements for physical health care.

Clinician Time Constraints

Patients’ discussions with clinicians about the nonmedical issues patients are facing take time, said Thomas J. Smith, director of palliative medicine at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, and professor, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Having standardized questions prepared in advance can help oncologists initiate a discussion on difficult topics. He noted that key components of palliative care are clinician assessments of patients’ symptoms, patients’ understanding of their illness, and patients’ and coping ability. This assessment typically requires between 30 to 60 minutes. Smith added that oncologists rarely have that much time to spend with patients.

Lack of Financial Incentives

Several speakers including Nancy Keating, professor of health care policy and medicine at Harvard Medical School, pointed out that health care payers typically do not look at overall, long-term benefits to the patient when providing reimbursements. They are more willing to pay for costly treatments that might provide short-term survival gains instead of behavioral health care that would improve quality of life for a longer period. Keating said that emerging care delivery and payment models, such as the Oncology Care Model8 and other collaborative care models, focus on patients undergoing cancer treatments, not on survivorship care. She said that cancer survivorship care is often shared with primary care and other specialties, and it is challenging to attribute who has primary responsibility for providing care in these settings. Keating added that fee-for-service models do not cover or incentivize care provided outside of office visits and also do not incentivize care coordination among multiple members of the care team. Keating said that an alternative payment model would typically incorporate a small number of clinically meaningful and important quality measures, including PROs. However, measuring survival, which may be the most important outcome, requires long-term follow up. She

___________________

8 See https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/oncology-care (accessed August 20, 2021).

added that this kind of long-term follow up is often not possible when patients continually shift from one health care system to another.

Jennifer Malin, senior medical director of oncology and genetics at UnitedHealthcare, said that lack of continuity in patient enrollment in the same health plan makes long-term payment models difficult to implement. She pointed out that individuals typically enroll in a commercial health plan for less than 2 years before changing plans, either because they change employers or their employer changes health plans. Malin stressed that this lack of long-term follow up on patients serves as a disincentive to addressing the long-term consequences of cancer care. Shulman agreed with Malin, noting that the inability to track patients long term is a major shortcoming that contributes to the lack of information on adverse effects of cancer treatments.

Lara Strawbridge, director of the Division of Ambulatory Payment Models at the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), said care should be patient centered, and evidence based, and that payment incentives can help promote this type of high-quality care, which ideally will lower expenditures. She suggested de-implementing approaches that are associated with lower quality-of-life measures and leveraging approaches that offer high value.

Data Gaps and Lack of Coordinated Electronic Health Records

Participants discussed the scarcity of long-term evidence on how treatments affect various populations. Assuming patients stay in the same health care system over time, information on long-term effects of cancer treatments could be garnered from EHRs and other patient databases, Shulman added, but will be dependent on accruing better structured data in EHRs. Malin agreed but noted that patients often receive care in different health care systems whose databases are not connected and cannot be linked with other relevant databases, such as cancer registries, claims, and genomics databases.

Other speakers highlighted the lack of interoperability among databases. Joseph Unger, associate professor of public health sciences at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and researcher and biostatistician at the Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) Cancer Research Group Statistical Center, pointed out that there are numerous regulatory hurdles to overcome, including those related to patient privacy. He noted that to comply with privacy regulations, many databases do not include the patient identification information needed to extract patient data from other databases. Baker added that the Privacy Rule promulgated under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulates issues regarding the use of patient information for research purposes, and that this needs to be addressed to successfully increase patient enrollment in survivorship research.

Other participants noted the lack of harmonized terminology to enable combining databases. Flowers said that, for example, some databases used the term “non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma” as a diagnosis, but now there are many subtypes of this cancer, each with their own specific labels. He noted that each dataset contains information that is accurate but that without harmonization, the data may even conflict due to different terminology. He added that the recent addition of genomic data further amplifies this problem by creating more refined labels for cancers that were once grouped together.

Missing data is another challenge when collecting and combining data, noted Lynne Penberthy, associate director of the Surveillance Research Program at NCI. She said that missing data can influence the accuracy of research findings interpretations. Collecting a complete dataset for research on survivors of AYA cancers in particular can be especially challenging due to passive refusals, a situation in which patients do not respond to repeated phone calls to schedule follow-up visits. Baker said that passive refusal may be due to patients’ schedule conflicts, or costs related to missing work and income, time constraints, and other cost issues. He said that convenience needs to be improved, and new recruitment methods are needed to increase participation of the AYA population in research.

OPPORTUNITIES TO REDUCE ADVERSE CONSEQUENCES ACROSS THE CANCER CARE CONTINUUM

Participants suggested a number of strategies for meeting the challenges in addressing the adverse consequences of cancer treatment. These strategies include making care more personalized, patient centered, holistic, and equitable; improving clinician education training and support; and collecting and integrating more data. Other strategies include using telehealth and other technology options to assess care needs and improve access to care, devising and applying policies that provide appropriate incentives, supporting new models of care and insurance coverage, and establishing and implementing standards and guidelines.

Patient-Centered, Holistic, and Equitable Care

Patient-centered care is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensures that patient values guide all clinical decisions (IOM, 2008). Randall Oyer, medical director of oncology at Penn Medicine Lancaster General Health, encouraged clinicians to put the patient and their goals at the forefront throughout the cancer care continuum. Karen Sepucha, director of the Health Decision Sciences Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, and associate professor, Harvard Medical School, added that clinicians need to ensure that patients have a voice in their care.

Shared Treatment Decision Making

Shared treatment decision making is an important element to patient-centered care. Alfano said that it is essential to begin shared treatment decision making as soon as a patient is diagnosed with cancer, to enable a patient’s care team to prevent or treat early the adverse effects of treatment, and to improve long-term outcomes. Several other speakers noted that the key to shared decision making is informing patients about their treatment options and the possible consequences of those options and how they might be addressed. Robison stressed that it is important for cancer survivors to understand what is known about their possible long-term health outcomes. Conway said that determining how much to share about future potential effects of a treatment requires careful attunement to individual patients’ wishes. Smith noted that patients could be assertive about the type and quantity of information they want from their health care team.

Scroggins said that shared decision making is often lacking in the care of underserved populations, who may not feel comfortable asking questions and may think their options for care are limited. She stressed that everyone should be given sufficient information to be actively involved in their decision making. Participants discussed the different communication preferences among patients. While some patients may want to be involved in their treatment decision making, others are more ambivalent about being involved with their treatment decisions. Sepucha also said that the degree to which patients want to be involved in their treatment decision making can change over time. When patients acquire more information, they often want to participate more (IOM, 2013). She said that providing patients with information can often help them to understand what their role in treatment might be, and to affirm that they have a lot to contribute to their own treatment. Sepucha said that decision making can be an extra burden for people already dealing with a cancer diagnosis. Shelley Fuld Nasso, chief executive officer at the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship, said that clinician communication skills are crucial, even for those patients who prefer having their care team make treatment decisions. Scroggins said “We need to make sure the system works for everyone regardless of where they are on the continuum.”

Several participants—including Sepucha and Melisa Wong, assistant professor in hematology/oncology and geriatrics at the University of California, San Francisco—stressed that a key component to shared decision making is determining the goals and concerns of both patients and their caregivers in care planning. Sepucha said that clinicians often focus on giving patients information and rarely take enough time to assess what matters most to each patient. She said that, for example, a younger patient might be most concerned with preserving their fertility, whereas an older patient might be more concerned with preserving their mobility and independence. Wong encouraged

clinicians to be aware of the interpersonal dynamics between patients and their families and to try to engage families in decision making when appropriate. She added that it is essential to ask patients directly if they have any financial concerns and to include those in developing the care plan. Zafar agreed that it is important to have family caregivers involved when discussing treatment options, and cited an example of a patient who was totally dependent on his spouse to transport him to his clinic appointments.

Sepucha said that patients can be aided in their decision making by using decision support tools. A Cochrane-pooled analysis of more than 100 randomized controlled studies on patient decision aids on a wide range of topics reported that the decision aids were effective in informing patients, increasing their knowledge, and helping them be more engaged and involved in the decision making (Stacey et al., 2017). Sepucha stressed that a combination of providing decision aids to patients along with teaching clinicians enhanced communication skills is the most impactful intervention to improve shared decision making.

Patient–Clinician Communication

Smith stressed the importance of effective clinician communication with patients and their families. He said that clinicians should not be afraid to talk with patients about sensitive topics regarding their treatment because patients are likely to be thinking about those topics already. Several participants said that clinicians need to recognize the emotional impact of a cancer diagnosis on patients and to provide patients with written information about their treatment options and potential adverse consequences. Sepucha, Smith, and others also stressed that it is critical to provide written information that is easily understandable and that can be taken home, reviewed, and shared with others involved in shaping care decisions. This relieves patients of the pressure to understand everything during a single visit. Gaines noted that often, patients are terrified after receiving a cancer diagnosis and cannot process oral information. Their fear also makes them inclined to accept any treatment, no matter how dire the potential consequences, if it might enable them to live longer, she added. “At a horrible moment to be making a decision, we’ve got to build the tool kit to help patients make a more informed decision,” Gaines said.

Harpham said that inaccurate information can lead to false hope, so it is important for clinicians to provide and nurture realistic hope when conveying information to their patients about their cancer diagnosis and treatment options. Wong said that people may be willing to undergo more risks and experience side effects if they are expecting a cure. Shulman suggested that institutions could take a structured approach to helping clinicians communicate with patients about their treatment or palliative care options.

Avoiding Decision Regret

J. Leonard Lichtenfeld, independent consultant, shared his experience with a patient who had been treated aggressively for esophageal cancer and then passed away. He said he received a phone call from the distressed sister of the patient, who told him that if she and her sister had understood the consequences of treatment and the likelihood of success, they would have made different choices on how to proceed. Bynum noted that decision regret often occurs among the children of geriatric patients with cancer. Smith said that patients are less likely to have decision regret if they are prepared for what may happen during treatment. A lot of decision regret stems from patients having unrealistic expectations or being completely surprised by adverse consequences, Sepucha added.

Smith suggested that clinicians write down the top 5 to 10 adverse consequences of treatment that patients are most likely to experience or are most concerning, and then explain to the patient and their family how serious those consequences are as well as what could be done about them. This simple process could help avoid decisional regret, Smith stressed.

Sepucha added that treatment decision making is an evolving process. She said that clinicians should continue to check in with patients about their satisfaction with their decisions in case adjustments can be made based on the patients’ experiences with the treatment. Such actions can also mitigate decision regret. Zafar added that asking patients what is most important to them and then designing a treatment around that can also help avoid decision regret.

Inter-Clinician Communication

Bryant said that cancer care outcomes can be improved with effective communication and teamwork. She noted that clinicians need to be competent in communicating with both patients and their families, and with other members of the patient’s care team. Their communication should be in a responsive and responsible manner that supports a team approach to the maintenance of health and the treatment of cancer, she said. Bryant said that Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance of Patient Safety is a tool designed for health care professionals to improve patient safety and quality through effective communication (King et al., 2008).

Javid Moslehi, associate professor of medicine and director of the cardio-oncology program at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, added that there are now hybrid subspecialties, such as cardio-oncology, to minimize cardiovascular and cardiometabolic toxicity during cancer treatment and to attenuate cardiovascular risks during cancer survivorship (see Box 3). Moslehi said that interdepartmental communication is crucial for care coordination.

Monitoring and Addressing Patients’ Physical and Psychological Symptoms

Several participants stressed the importance of ongoing monitoring and treatment of patients’ symptoms and adverse effects of their treatment, including those that develop years or decades later. Smith and Cella cited a study of patients with metastatic cancer in which some received the usual care, while others also reported their symptoms in a Web-based format (Basch et al., 2017). A patient’s worsening symptoms would trigger an e-mail alert to the

nurse responsible for their care, who addressed the symptoms with a clinical intervention. The study found that those who reported their symptoms survived about 5 to 6 months longer on average than those who did not. Smith also cited other studies of patients with lung cancer, which found that palliative care (monitoring and addressing symptoms and asking patients how they are coping) decreased patients’ reports of depression and anxiety, improved their quality of life, and increased their lifespan by nearly 3 months on average (Temel et al., 2010, 2011).

Several presenters said that patients should be monitored and treated for adverse effects beyond the physical measures. Participants suggested screening and addressing psychosocial and financial effects of the cancer on patients and their families, as well as the effects of concomitant diseases, and their functional status and quality of life. Wong suggested expanding the definition of cancer treatment toxicity beyond the short-term physical side effects. She said that the traditional narrow approach can miss longer-term side effects such as secondary cancers, financial and psychosocial effects, functional decline, and cognitive impairment. Bynum agreed, saying that much of the focus in cancer care has been on extending life with treatments, but often, quality of life is neglected.

Several participants suggested that clinicians should also inquire about and address any sexuality or body image problems patients have due to their cancer or cancer treatment. Women who have had surgery to remove their breasts, ovaries, or uterus often struggle with their new body image and can feel stigmatized or shamed by people who judge them as not being feminine enough, Henley, Scroggins, and Darien noted. Harpham added, some cancer treatments can cause premature menopause or impair sexual function.

Smith suggested that clinicians watch for signs of depression and demoralization in their patients, which can often can be induced or exacerbated by a cancer diagnosis and treatment. Cella also stressed the need for more rigorous assessment of cancer patients’ psychological symptoms. Routine distress management has been recommended as a routine part of cancer treatment (IOM, 2008), and Cella said that for a cancer center to receive accreditation from the American College of Surgeon’s Commission on Cancer, every patient treated at the cancer center must have distress screening9 at least once during their treatment (Ehlers et al., 2019). But Cella said that only one distress screening assessment is insufficient to appropriately monitor and treat cancer-related distress. He mentioned that there are several psychological screening tools for

___________________

9 The Association of Community Cancer Centers defines distress screening as a brief method for prospectively identifying and triaging cancer patients at risk for illness-related psychosocial complications that undermine the ability to fully benefit from medical care, the efficiency of the clinical encounter, satisfaction, and safety.

patients (Mitchell et al., 2011), and he suggested more consistency in reporting and tracking psychological symptoms.

Learning Health Care System and Patient Stratification

To provide more personalized care, Keating and Alfano suggested digitally tracking patient symptoms and quality-of-life information and embedding that data in a learning health care system that integrates research and practice. They said that such a system could provide more accurate predictions of an individual patient’s risk of developing adverse consequences from their cancer treatments.

Alfano said the data could also help stratify patients according to their individual risk. She noted that such stratified cancer care has already been implemented in the United Kingdom with successful results. In the National Health Service’s pilot program, the vast majority of patients with cancer were followed in a primary care–led model with self-care and supported self-management and open access back to the oncology team wherever possible (NHS, 2013). A smaller number of patients at higher risk were treated in a shared care model, and an even smaller number of the highest risk patients were treated via complex case management provided through a multidisciplinary care team. Results from the pilot program showed that it better met patient needs and improved clinical efficiency, Alfano reported. Benefits of the new system included freeing up more oncology visits for new patients, thereby reducing their wait times by 34 percent, and improving follow-up testing by 20 percent. Alfano mentioned that the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) has been collaborating with ACS to determine how such a model of cancer care might be implemented in the United States (Alfano et al., 2019).

Other presenters also called for stratifying patients by risk. Robison suggested stratifying patients soon after diagnosis to choose a frontline treatment that minimizes their toxicity exposure. Bhatia stressed that early identification of patients who are at the highest risk of developing complications from their cancer treatments could prevent morbidities later on. She said that those at the highest risk could receive earlier and more intensive surveillance to reduce or prevent the burden of those complications. Bhatia said that at the time of a breast cancer diagnosis, a genetic blood test may reveal that a patient has an 80 percent risk of developing a secondary breast cancer. This may lead to the decision not to use chest radiation to treat this patient’s cancer and to use alternative treatment strategies, or, if radiation therapy is used, screening the patient earlier or more intensively for breast cancer. Another possibility is to prescribe low-dose Tamoxifen for girls who received chest radiation during their adolescence, to reduce their risk of breast cancer if biomarkers support such a treatment strategy, Bhatia said. To reduce the risk of heart failure

stemming from the use of certain chemotherapies, patients receiving those therapies could be given preventive drugs to reduce their cardiac risk. According to Bhatia, such stratification and prevention is currently being explored in clinical trials. Malin suggested that clinicians shift from preventive care for the average-risk individual to stratifying all patients with cancer to enable patients to receive appropriate preventive care throughout the cancer care continuum.

Alfano also suggested that self-management should be the cornerstone of cancer survivorship care just as it is in the management of other chronic diseases. She recommended educating, empowering, and facilitating patients toward self-managing the adverse consequences of cancer treatment through survivorship webinars and other events.

Financial Hardship

Many participants suggested that clinicians should screen patients for the financial burdens of cancer care to identify any potential financial hardships that could be associated with their treatment. Henley and Samuel-Ryals said that health care institutions should provide patients with access to social workers or financial counselors if they need help with paying for their cancer care. Zafar also suggested that clinicians include financial concerns when discussing care goals with patients. He stressed that just as clinicians assess, monitor, and try to prevent or ameliorate patients’ fatigue due to their cancer treatments, the same should be done for financial issues. Burris suggested that health care institutions could work with vendors to assist patients with childcare, transportation, and all sorts of costly ancillary aspects of their cancer care.

Champion Health Equity

Many participants said that both clinicians and their institutions are key in improving health equity. Samuel-Ryals suggested that institutions conduct an assessment of their culture of health equity to increase institutional awareness and to develop and execute a plan to achieve their health equity goals. She said a Diversity and Cultural Proficiency Assessment Tool for Leaders10 developed for leaders within hospitals by the American Hospital Association, could be a guide. Also, Samuel-Ryals suggested that hospitals and practices prioritize real-time data collection and monitoring of patient’s psychosocial and socioeconomic concerns, stratified by race/ethnicity and other social categories. She said that this approach could be facilitated through PROs and

___________________

10 See https://www.aha.org/system/files/2018-02/DiversityTool.pdf (accessed August 12, 2021).

real-time registries, such as the one developed by researchers at the University of North Carolina and the Greensboro Health Disparities Collaborative as part of the National Institutes of Health’s funded study, Accountability for Cancer Care through Undoing Racism and Equity.11 In addition, Samuel-Ryals suggested that hospitals and practices could use clinical decision support tools to mitigate implicit bias during the clinical decision-making process.

Samuel-Ryals noted that structural racism is often codified in an institution’s policies and procedures, as well as in laws and in routine standards and practices, but she said that equity can be codified as well. She suggested, for example, that funding bodies could require research teams to include members of the community participating in the clinical research, and then monitor to ensure this requirement is met. She also suggested incorporating equity-related goals in accreditation standards.

Justin Bekelman, professor of radiation oncology and medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, suggested the need to invest in a diverse, culturally competent workforce to achieve better health equity.

Emily Tonorezos, director of the Office of Cancer Survivorship at NCI, suggested adapting psychological stress assessments and care management programs that are culturally appropriate for underserved populations, including LGBTQ populations. Other speakers also suggested that researchers champion diversity in clinical trial enrollment. Harpham suggested improving the diversity in clinical trials throughout the entire process, from the inception of the research idea, trial processes and procedures, recruitment, and meeting the needs of the enrollees. She added that research that leverages big data needs to include data from diverse populations.

Clinician Education, Training, and Support

Participants made several suggestions to improve clinicians’ education, training, and support to better address the adverse effects of cancer throughout the cancer care continuum. Shannon MacDonald, associate professor at Harvard Medical School, and Gary Lyman, professor in the Public Health Sciences Division and Clinical Research at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and professor of medicine, public health, and pharmacy at the University of Washington, suggested early training for medical students on how to balance treatment risks and benefits. Lyman said that clinicians can learn to be more comfortable recommending a less intense treatment that will give a patient fewer long-term adverse consequences and a better quality of life.

___________________

11 See http://greensborohealth.org/accure.html (accessed August 12, 2021).

Sepucha suggested building the communication skills and competencies for health care teams to elicit patients’ preferences. Gaines suggested that, in addition to rigorous scientific training and current knowledge on cancer treatments and their adverse effects, the humanity of patients should be reinforced in medical education and clinicians should be supported in their efforts to be attuned to the individual needs of their patients.

Moslehi suggested teaching all members of the care team how to prevent adverse effects in cancer survivors, including with cardiologists and other clinicians beyond oncology specialists. Although prescribing the follow-up care for cancer survivors falls under the domain of oncologists, he suggested that it is important for all clinicians to be able to address the wide spectrum of adverse effects from cancer treatment. This is especially true for patients who are at higher risk for disorders that fall outside the range of a single specialty, he added.

Bryant stressed the need to promote interprofessional education and practice on ensuring access to palliative care and appropriate pain management, as well as to psychosocial services. She suggested the development of certification programs to provide training on how to care for patients who have experienced a cancer diagnosis. Also, she advocated for passage of the Palliative Care and Hospice Education and Training Act.12 Timothy W. Mullett, professor of cardiothoracic surgery at the University of Kentucky and chair of the Commission on Cancer, also suggested teaching primary care providers more about cancer care. Bryant and Samuel-Ryals also suggested that health equity competency should be part of medical education and oncology board certification. Henley suggested that researchers could benefit from what she called “re-education” about the minority communities they study; that is, researchers should learn about the history of medical abuse of these communities to understand and address the hesitancy of Black and other minority patients to volunteer for clinical studies.

Data Collection

Shulman said that data can provide a better understanding of the adverse effects of cancer care as well as how to prevent and treat them. Traditionally, researchers determined the adverse consequences of cancer treatments from clinical trial data. But Kelly Magee, senior clinical director at Flatiron Health, said that because of the limited amount of time patients are followed on clinical trials, the full breadth of adverse effects of treatments over a long period of time is not well known. Trial data also lack adverse effects of cancer treatments

___________________

12 See https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/647 (accessed August 12, 2021).

in patients with concurrent illnesses or other conditions that exclude them from participating in clinical trials. For example, patients with autoimmune disorders are usually excluded from receiving experimental cancer immune therapies in clinical trials. Data comparing outcomes from one treatment to another are also often lacking, Magee noted.

Due to the limitations of clinical trial data, several participants suggested using adverse effects information in EHRs. However, Magee said that much of the data on adverse events recorded in EHRs is in an unstructured, free-text format, which requires manual curation to transform it into standardized content that researchers can analyze. Data may also be missing that would provide the full picture of a patient’s care. For example, an oncology practice’s EHR data may be missing data from other specialists, such as cardiologists, who treat patients’ adverse effects. The data can be acquired and scanned into the EHR. However, data may still be missing if adverse effects that do not require follow up or intervention, such as low-grade fatigue, do not get recorded in the medical record. Shulman suggested including both patient-reported and clinician-reported outcomes in EHRs, which could be structured for learning purposes.

Magee suggested that automation and machine learning can also be leveraged to support curation of unstructured data. Also, she suggested adopting shared standard terminology, data models, and mapping approaches for routine clinical documentation to facilitate data sharing. Magee said that this vision of an EHR designed to support the needs of patients and oncology care team members would require abandoning paper charts and viewing the EHR as a dynamic learning platform. To create such a system will require the collaborative efforts of patients, payers, clinicians, sponsors, researchers, regulators, and EHR developers, she noted.

Shulman and other participants suggested ways to increase the amount of data captured in EHRs, including toxicities, concurrent illnesses, quality-of-life measures, and PROs. Shulman said that patients who enroll in clinical trials should be monitored for some time after those studies end. He also suggested having databases that combine data from multiple sources, including EHRs, registries, clinical trials, genomics testing, and claims data. Penberthy reported on the SEER database and its capacity to link to other databases (see Box 4).

Michael Halpern, medical officer in the Healthcare Delivery Research Program at NCI, said that in addition to the SEER database, NCI has other data resources that link psychosocial and socioeconomic effects of cancer and cancer treatments to SEER. Data from the Medicare Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey, which is administered by CMS, allows assessment of patients’ experience with their health care. Additionally, the Medicare Health Outcomes Survey data provide assessment of quality of

life, symptoms, depression, and activities of daily living. Also, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Experiences with Cancer Survivorship Supplement provides information on financial and employment outcomes, as well as conversations with health care providers on financial burden, and mental health measures. Halpern noted that he coordinates the NCI Patterns of Care study, a congressionally mandated research initiative that links manually curated information from medical charts to the SEER registry data. It assesses detailed treatment patterns, disparities in care, symptoms, and (for the 2019 Patterns of Care study13) patient–physician conversations about cost. The Healthcare Delivery Research Program14 includes a specific area of interest on financial burdens of cancer care and cancer treatment, as well as factors that reduce and mitigate economic hardship, Halpern explained.

___________________

13 See https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/poc (accessed October 28, 2021).

14 See https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov (accessed August 12, 2021).

Lawrence Kushi, director of scientific policy at Kaiser Permanente (KP) Northern California, reported on KP’s integrated health care system, which includes an EHR with more than 15 years of records from multiple sites across the United States (see Box 5). Kushi said that current data systems should be improved to produce real-time data to guide clinical care. He said that SEER and other cancer registries contain rich information to inform some aspects of patient care, such disease stages. However, the data are not reported in a timely fashion for next-day use. Also, he said there is a general need for databases that incorporate details of radiation therapy, which exists but may not be accessible outside of radiation oncology or integrated into EHR databases.

Unger reported on a novel data linkage between SWOG’s EHRs and Medicare’s database (see Box 6).

Yabroff suggested that a national coordinated data infrastructure for informing care delivery and research could help ensure delivery of better cancer care in the future. Similarly, Penberthy suggested creating a virtual pooled registry system that links data with all registries in the United States. Such a registry would enable tracking of the incidence of new cancers in cancer survivors.

Flowers and Shulman said that some health systems, such as the University of Pennsylvania system, have already begun to collect PROs on adverse effects and respond in real time, and that the PROs are collected as structured data with the EHR. A database system could also help identify patients more likely to have adverse reactions to certain cancer treatments so clinicians could select therapies to prevent the adverse events, Flowers noted. Scott Ramsey, professor of cancer prevention and research at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and director of the Hutchinson Institute for Cancer Outcomes Research, stressed that data will only be compelling in the clinical sphere if it is actionable and closer to real time.

Technology

Many participants suggested ways that technology to can be used to both prevent adverse consequences of cancer treatment and address the consequences when they occur. Some suggested broader use of decision support tools for patients and clinicians. Others noted that technology could help improve the quality and interoperability of EHR databases. Several participants said that technology could be leveraged to enhance the capabilities of telemedicine in both clinical research and care. Shulman noted that video-enabled telehealth visits can engage family members that may not have otherwise participated in a patient’s office visit. Other participants also suggested using advances in technology to support implementation of a learning health care system, and developing and deploying EHR survey tools that can be used for both research and care.

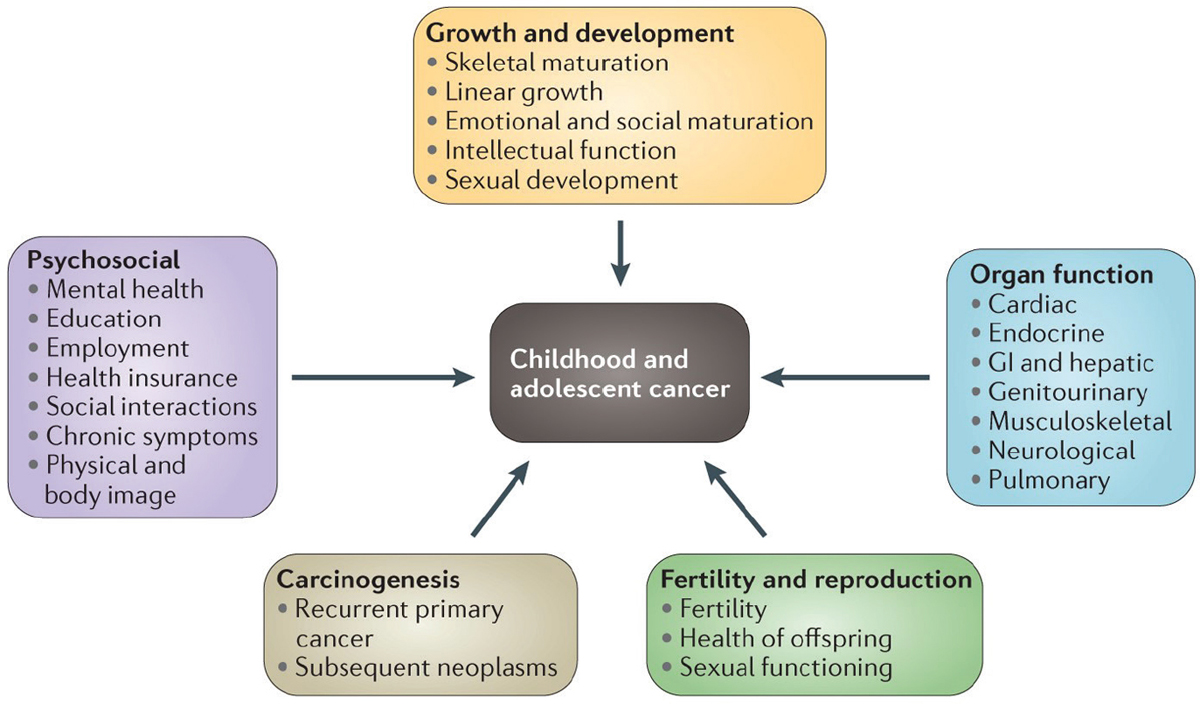

Alfano suggested building information technology systems that can assess patient needs and reduce health disparities (see Figure 3). She described such a system as a data repository that is able to pull data from multiple sources including EHRs, PROs, implantable or wearable devices, and other sources that are continually integrated, updated, and expanded. The collected data would then be connected to an intervention repository. She said that the data repository should also include predictive analytics that stratify patients by risk, and prescriptive analytics that make treatment recommendations. All the treatment recommendations should be accumulated into a national repository that enables continuous assessment of patient and system outcomes to support learning, Alfano concluded.

Tonorezos suggested leveraging machine learning to gain a better understanding of some of the adverse effects of cancer treatments. She said that KP researchers have applied machine learning to its extensive EHRs to estimate patients’ risk of developing chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, a common painful and potentially debilitating effect on patients’ nerves. If patients at risk are identified prior to treatment, then oncologists can

NOTE: EHR = electronic health record; ePRO = electronic patient-reported outcomes; IoT = Internet of Things (e.g., implantable or wearable devices).

SOURCES: Alfano presentation, November 10, 2020; adapted from Alfano et al., 2020.

use this information when discussing treatment options with patients, Tonorezos said.

Baker suggested using EHR tools to support clinical care and research for survivors of AYA cancers. He described a comprehensive survivorship PRO survey that was incorporated into an EHR system. He said that the survey was used to collect patient symptoms including pain, fatigue, sleep disturbance, distress, anxiety, and depression. He mentioned that the survey also contained questions on cancer screening behavior, cardiovascular risk assessment, and questions related to infertility. Prior to each of their office visits, patients are prompted by e-mail to fill out the online survey, which has a research consent embedded within it. An automatically scored summary of their responses to the surveys is then sent to their clinicians. The summary highlights relevant symptoms as well as any missing cancer or cardiovascular risk screening. The data collected in the survey can then be exported for research. Researchers can also use the data to identify and recruit patients with specific adverse outcomes for their studies. In addition, the survey system creates individualized treatment summaries and survivorship care plans, including cumulative dose tracking of relevant drugs whose effects on cardiac functioning is dose dependent. Baker noted the survey system could be combined with telehealth to provide remote clinical care for AYA cancer survivors.

Policy Opportunities

Workshop participants discussed several policy measures that could help address the adverse effects of cancer treatments. These include the creation of new models of cancer care delivery and payment that encourage equitable care; developing standards and guidelines for quality, whole-patient care for cancer patients and survivors; setting standards for data; and providing adequate insurance reimbursement for cancer care.

New Models of Collaborative Care

Several participants said that the need for more collaborative and interprofessional care of cancer patients and survivors is vital. They suggested that health care organizations should employ an array of nonmedical patient support staff, including financial counselors, psychologists, social workers, occupational and physical therapists, and patient advocates and navigators to assist in the care of patients diagnosed with cancer. Samuel-Ryals added that support staff are especially needed in hospitals and care facilities that provide care to a disproportionate share of underserved patients.

Fuld Nasso stressed that there is a disconnect between the time constraints on clinicians and the holistic care that patients with cancer require. It is critical to explore other ways of delivering care, including team-based formats, especially for treatment decision making, she said. Darien and Lichtenfeld agreed, and stressed the importance of nurses who often play a primary role in answering patients’ questions and helping them through the decision-making process.

Alfano added that patients benefit from equitable and timely access to a much bigger multidisciplinary team for cancer care and survivorship that includes cancer rehabilitation, palliative care, psychosocial care, exercise and nutrition programs, dentistry, genetic counseling, cardio-oncology, endocrinology, neurology, audiology, and other specialists needed to meet patient needs. Bekelman also stressed the importance of collaborative and team-based care.

Cella suggested engaging a care manager or navigator to coordinate specialty, primary, and behavioral health care in a collaborative care model. He also said that positive social networking should be encouraged to provide comfort and support for people coping with psychosocial concerns related to cancer. Cella stressed that both drug and psychological treatments for depression tend to have short-term efficacy, whereas the benefits from collaborative care models tend to persist longer (Li et al., 2017). A collaborative care model, Cella said, utilizes a multidisciplinary team of specialty care clinicians as well as resources in the patient’s social community. A case manager coordinates the team, and develops a treatment plan. Tonorezos said that collaborative care should be provided early in the treatment course, or at diagnosis, in order to

integrate cancer care seamlessly with primary care, cardiology, geriatrics, and other supportive care specialties.

Kevin Oeffinger, professor of medicine, director of the Duke Cancer Institute Center for Onco-Primary Care at Duke University, and primary care doctor, noted that because cure rates for many common cancers are so high, most cancer survivors are dying from cardiovascular disease and not cancer. That often is due to benign neglect or not paying attention to non-cancer–related illnesses, such as hypertension or diabetes, he said. For example, women aged 50 years and older who are diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer are more likely to die from a cardiovascular event than from their cancer 7 years after diagnosis (Bradshaw et al., 2016). Also, most women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer have high blood pressure, high lipid levels, or diabetes that predispose them to developing cardiovascular disease (Chen et al., 2012). Yet, one study of early-stage breast cancer survivors receiving care in an integrated health care system found that the patients’ adherence to statin therapy dropped from 75 percent adherence in the year before diagnosis to 25 percent adherence after the first year of breast cancer treatment. The study also reported that the patients’ statin adherence levels did not rise much above those low levels at 3 years post treatment (Calip et al., 2017). These investigators found that medication adherence was higher if the care of patients diagnosed with breast cancer was co-managed by a primary care provider (Calip et al., 2017).

Oeffinger said that the primary care physician should be an integral member of the care team during or soon after cancer therapy, but currently, that seems not to be the case. He suggested incorporating primary care physicians into the cancer care team at diagnosis, especially if the patients are expected to have many more years of life. He also suggested that primary care physicians need to be integrated into cancer care medical homes. Mohile agreed and said that due to the lack of geriatric specialists, there is a need for primary care physicians, cancer care teams, and other specialists to work together to address the complexity of caring for older adults.

Bhatia said that pediatric survivors of cancer also need collaborative care. That care should include oncologists partnering with pediatric primary care physicians, she said. Bhatia cited a study that found that primary care physicians’ comfort levels were higher when collaborating with a pediatric oncologist to provide health maintenance care for survivors of childhood cancers compared with independently providing such care. Only 30 percent of primary care physicians were confident in their knowledge regarding immunizations for survivors, for example (Wadhwa et al., 2019).

Bhatia and Baker also emphasized the need for specialized centers devoted to treating survivors of pediatric and AYA cancers to ensure that they receive appropriate care.

Mullett noted that most patients with cancer receive care at multiple specialized facilities (e.g., they receive chemotherapy or radiation treatments at one facility and surgical care at another one) (Gondi et al., 2019), so it is very important to develop a portable mechanism for survivorship that enables payers to identify and reimburse health care providers across multiple facilities for a single patient.

Oncology Care Model

Keating reported on the experimental Oncology Care Model (OCM) developed by CMMI of CMS.15 The model is intended to align financial incentives to improve care coordination, appropriateness of care, and access to care for Medicare beneficiaries undergoing chemotherapy. OCM involves payment targets for episodes of cancer treatment and quality metrics to ensure that patients are receiving quality care. Practices participating in OCM can bill for monthly payments of $160 per Medicare beneficiary per month during 6-month episodes of care for patients receiving chemotherapy. These payments are intended to support delivery of enhanced oncology services. Keating noted that some practices have used the payments to hire social workers and therapists to better integrate behavioral health services into their practice. The practices then bills for all other care under fee-for-service arrangements as they would under standard fee-for-service Medicare. If reduced spending and quality goals are met, practices would receive a performance-based payment. The performance-based payment quality measures currently include 5 measures of care during patient episodes: use of emergency department (ED) visits, hospice enrollment, assessment of pain and depression, providing care plans and follow-up plans, and patient-reported experiences of care.

Practices participating in OCM are required to use certified EHRs and to use the data for continuous quality improvement, Keating said. OCM practices are also required to provide enhanced services, including 24/7 access to clinicians, patient navigation, and care consistent with national guidelines. They must also furnish a cancer care plan for each patient. The care plan should highlight the diagnosis, prognosis, treatment goals, treatment plan, expected response to treatment, potential benefits and harms of treatments, and estimated out-of-pocket costs. In addition, OCM practices must provide their patients with advanced care plans, psychosocial plans, and survivorship care plans. Malin added that to incentivize shared decision making, both

___________________

15 See https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/oncology-care (accessed August 12, 2021).

OCM and UnitedHealthcare’s Cancer Episode Program16 offer comprehensive payment to practices who can be creative in how they leverage those resources to support patients as part of the treatment team.

Strawbridge said that many OCM participating practices have reported that they did not realize the extent or burden of the ancillary challenges, such as mental health issues and financial burdens that their patients face, until they began participating in OCM. She also noted that many clinicians initially expressed concern about the requirement to have a discussion with patients about their out-of-pocket expenses because they were worried that having such discussions would make patients assume that the clinicians were basing their treatment decisions on cost rather than on what is best for the patient. “But over time, the culture has begun to shift and folks are appreciating that they have a better sense of the financial impact of treatment on their patients as a result of having those conversations,” she said.

Keating reported that an assessment of the first 18 months of OCM implementation found that OCM led to an insignificant cost savings overall (Hassol et al., 2020, 2021; Keating et al., in press). Keating said that when analyses were stratified to examine low-risk care episodes (e.g., patients receiving hormonal therapy) versus high-risk care episodes, the results showed that payments increased for low-risk episodes and decreased for high-risk episodes for OCM relative to comparison episodes. Keating noted that OCM had no impact on hospital-based services, including hospitalizations and ED visits. Patients also did not report receiving better care, including improved decision making, symptom control, or survivorship care, in an OCM practice compared to standard practices (Hassol et al., 2020, 2021; Keating et al., in press). Strawbridge said that she hopes the full potential of OCM has not yet been realized. That may change after more years of evaluation, but CMMI has already begun to assess how to incorporate lessons learned from OCM in potential new oncology model,17 she added.

Other Models for Oncology Care Delivery and Payments

Strawbridge also described the proposed CMS Radiation Oncology Model,18 which provides 90-day, episode-based payments to practices for patients initiating radiation therapy for 1 of 16 cancer types. This model is

___________________

16 See http://graphics8.nytimes.com/ref/business/UHCCancerCareProgram.pdf (accessed August 12, 2021).

17 See https://innovation.cms.gov/files/x/ocf-informalrfi.pdf (accessed September 16, 2021)

18 See https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/radiation-oncology-model (accessed August 12, 2021).

intended to improve the quality of care for patients receiving radiotherapy for cancer and to move toward a simplified and predictable payment system. The goal is to encourage better adoption of evidence-based care by making predictable and stable episode-based payments, and to reduce inappropriate utilization through a shift from payment per dose fraction to bundled payment that does not vary by how much care is delivered during the episode.

Keating said that another cancer care delivery model, proposed by ASCO,19 is the Oncology Medical Home, which seeks to provide patient-focused care that is accessible, efficient, and high quality, and that is optimized based on evidence from quality measures. The Oncology Medical Home model shares some features of OCM, including accountability for costs of care, although that accountability excludes the cost of anti-cancer drugs, she said. The model attempts to improve care delivery and patient outcomes while also controlling spending by reducing ED visits (Kuntz et al., 2014). Keating explained that the model provides three bundled payments to the participating oncology practice: when a new patient enters treatment, a monthly payment during treatment, and a final payment during active monitoring. The 12-month survivorship payment is a unique element. Keating cited evidence that this patient-focused care delivered in oncology medical home models is linked to reductions in ED visits and spending among patients undergoing cancer treatment (Colligan et al., 2017; Kuntz et al., 2014). Care for longer-term cancer survivors under this model however, has not been evaluated, she said.

Keating advocated for the delivery of survivorship care centered on patient need rather than centered around when office visits with individual clinicians are available. She said that such models should incorporate remote care and monitoring, as well as elements to stratify and distinguish patients who are receiving chronic treatment from those who have completed treatment. She emphasized that any patient-centered models should also prioritize health equity.

Disincentives for Providing Low-Value Care

David Howard, professor of health policy and management at Emory University, said that incentives are a powerful mechanism for changing clinical practice. He said that physicians are often slow or reluctant to abandon ineffective treatments, in part because fee-for-service reimbursement incentivizes the use of more aggressive treatment. In addition, some specialties are closely linked with providing specific treatments or using costly technologies, so it can be difficult for physicians in those specialties to reduce that use. Howard

___________________

19 See https://practice.asco.org/billing-coding-reporting/macra-quality-payment-program/ alternative-payment-models (accessed August 12, 2021).

also said that physicians are often reluctant to tell patients that further cancer treatment is unlikely to help them, and patients may demand more aggressive treatment, both of which can contribute to overuse of ineffective treatments. He added that cognitive inertia—by which people anchor their initial beliefs and are slow to uproot them in response to new evidence—is another factor responsible for physicians’ reluctance to de-implement ineffective practices.