8—

Investment Levels and Potential Opportunities

Introduction

Many kinds of investments can be made to ensure that the goods and services provided by nonfederal forests are sustainable. Some investments require an outlay of money with the expectation of a monetary return. Investments, especially in nature, might not require outlays of money, nor are the expected returns necessarily monetary. For example, maintaining some level of biodiversity can have the desired result of sustaining species without monetary investments. Innovative opportunities for investment are presented in this chapter.

Forest Investments

The capacity of nonfederal forests to supply goods and services to society is a function of private and public investments. These investments are made in an environment of complex interactions between forest landowners, public agencies, and various commercial and nonprofit organizations. Trends in investment in industrial and nonindustrial forestlands are of particular importance. Although industrial forests make up only 14 percent of the nation's timberland, they yield one-third of the nation's timber harvest. The importance of nonindustrial forests derives from their size (59 percent of the nation's timberland), harvest (half of the nation's timber harvest), and potential for increased harvest (Powell et al. 1993). Although the owners of industrial and nonindustrial private forests appear to invest to maximize profits, the investment and harvesting activities of nonindustrial-forest owners reflect the importance of nonmarket values (Newman and Wear 1993, Kuuluvainen et al. 1996). At present, higher prices are envisioned

for forest products, at least over the near term, as a result of decreased federal harvests (Haynes et al. 1995), which can be expected to affect investments and harvests in nonfederal forests (Adams et al. 1996) to the extent that price increases were not anticipated by landowners.

Forestland investments can be conceptualized either as establishing new forests with primary inputs of land, labor, or capital or as retaining existing forests with growing stock (Wear 1993). Some forestland investments require advance monetary outlays; others involve only opportunity costs. Some investments are made in the expectation of earning income or profit, whereas with others the expectation of return is nonmonetary. Specifically, investments in forestland can include the following:

- Keeping the forest intact, rather than allocating it to an alternative land use, such as agriculture or residential development.

- Allowing the trees with a potential market value to continue to grow and possibly increase in value.

- Protecting the forest against losses from wildfire, pests, pathogens, or vandalism.

- Developing and maintaining access, such as roads, landings, or trails.

- Management planning, such as timber harvest or estate planning.

- Pursuing management activities associated with particular objectives, such as tree planting, timber-stand improvement, or wildlife habitat enhancement.

- Subsidizing the forest in the form of cost-share programs, tax incentives, or technical-assistance programs.

Investment Environments

Investment Climate

The magnitude of goods and services provided by nonfederal forests and the protections afforded them depends on the willingness and ability of the American public to invest in them. This willingness and ability is tempered by broad economic swings in the nation and by the attractiveness of potential investments to the public and private investors. With the national political mood favoring reduction in government at all levels, the climate for government investment is not particularly positive. In recent years, the federal government has reduced investments in real and nominal terms in natural and environmental programs generally. With the devolution of federal action, the private sector and state and local governments should pick up a major share of future investments in nonfederal forests. Whether these investments are possible is yet to be ascertained. Obviously, the federal government has a role in creating a positive national economy in which investments in nonfederal forests will occur.

Landowner Investment Circumstances

Nonindustrial Private Owners

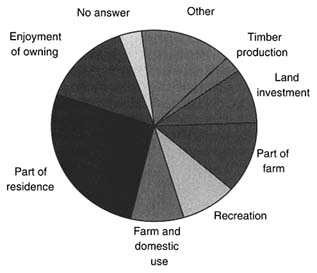

Owners of nonindustrial private forestland are diverse and have a variety of objectives which must be accommodated when they make investment decisions and obtain financial support. Many owners have multiple objectives, which usually complement each other rather than compete. Less than 10 percent of landowners identify the investment potential of the land as their primary reason for ownership, although it is a secondary reason for many (Figure 8-1). Few owners (less than 3 percent) identify timber production as their primary reason for ownership, but those owners control 30 percent of all private forestland (Birch 1996). Furthermore, management objectives for private forests are transitory and change with each new owner. Industrial forest landowners want to reduce the risk of raw-material shortages and insulate the enterprise from short-term price fluctuations. On the other hand, nonindustrial forest landowners have a variety of investment strategies, each of which requires special investment attention. Some investors are custodial and make no strategic investments, and others make incidental investments; many are speculators focusing on appreciation in land values, hobbyists investors looking for supplementary income from forests, or true investors reacting to price and other market conditions. As a result, researchers on investment behavior by nonindustrial forestland owners use a number of theories

FIGURE 8-1 Landowners' reasons for owning forestland (% of landowners). Source: U.S. Forest Service 1996.

on investment behavior (Royer 1988, Alig et al. 1990). The diversity is a challenge to public and private investment sources that package investment programs for target groups (Romm et al. 1987, Yoho 1985).

Industrial Owners

The wood-based industry owns over 71 million acres of timberland nationwide. From an investment perspective, the industry must deal with a number of circumstances that present potential risks and uncertainties (O'Laughlin and Ellefson 1982), including the following:

Producing timber on industrial forestlands. In many respects, the timberland owned fee simple by the wood-based industry is the nation's only forestland devoted exclusively to the production of timber used in the manufacture of wood products. Nearly all other forestland in the nation is owned and managed by landowners who have other objectives (for example, forest recreation and wildlife habitat). Public policies, such as taxes and regulations, can have a marked effect on the way such land is used and managed.

Relying on others for timber. Although the industry owns over 71 million acres of forestland, a large percentage of its timber is supplied by other sources. In the West, the primary source is publicly owned timberland, whereas in the East and South, the primary source is owners of private nonindustrial forests. A de-emphasis on timber production by any of those sources can pose difficulties for the industry.

Supplying uncertain markets. The industry manufactures products that are sold to diverse markets. Many of these markets, however, are uncertain for the industry in terms of existence, magnitude, and stability. The markets for some manufactured products, notably lumber and related construction material, are notoriously unpredictable. Federal policies that foster a healthy economy are important in reducing those uncertainties.

Sensitivity to production costs. Given the reality of uncertain markets, the timber industry must be especially sensitive to the costs of securing timber and the cost of product manufacture. Moving the cost of timber production and product manufacture on to the market is not always possible, given the uncertainty of many markets and their highly competitive nature. Public policies that impose costs on industry can adversely affect its financial health.

Responding to corporate owners. Most wood-based firms are corporations that must be responsive to the financial interests of their stockholders, and the rates of return on stockholder investments are an important measure of corporate vigor. Costs that deter from that are not generally acceptable.

Uncertain timber supplies. Access to dependable supplies of raw material, namely, timber, at acceptable prices is critical to the industry's ability to function. Wood-based enterprises consider it is essential that uncertainties regarding the availability of timber be eliminated or reduced to acceptable levels. How that is accomplished varies from firm to firm, although strategies generally include fee-simple ownership of forest property, supply agreements with owners of private forestland, and contracts (short and long term) to harvest timber from public forests. In recent years, uncertainties over access to timber supplies (and over timber production and harvesting) have increased substantially, most notably in the West over federal land.

The ability of the industry to operate and meet its corporate and social responsibilities is dependent on its access to timber as a raw material. Although the industry has improved its competitive position in recent years in terms of labor productivity and expanded exports, the industry remains sensitive to the federal role in influencing access to raw-material supplies and the industries' ability to manufacture timber products demanded by a variety of markets. Federal policies, especially tax and regulatory policies, need to be sensitive to the adverse impacts they might have on the cost of growing timber on industrial timberland and on activities involving the manufacture of wood products. Federal policies should also foster cooperative actions among public and private landowners (sustained-yield units, long-term timber supply agreements) that will enable industry to address uncertainties of access to long-term supplies of timber. Industrial initiatives to improve the sustainable management of industrial timberlands (for example, the Sustainable Forestry Initiative of the American Forest and Paper Association and the Forest Stewardship Council) should also be facilitated by the actions of government.

State and County Forests

State and county governments own nearly 64 million acres (9 percent) of the nation's forestland, most of which is in the Great Lake states (Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan), Alaska, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Washington. Some 24 million acres are located in five states, namely, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and New York, with 14 million in the three Great Lake states alone. The largest single state ownership (22 million acres) is in Alaska.

State and county forest-resource programs have been strengthened markedly over the past 25 to 30 years. Federal technical and financial assistance has been used in the process, although the assistance resulted from the state's initiative to obtain it. Important efforts to strengthen management of state and county forestland are illustrated in Box 8-1. Over a period of 25 to 30 years, Minnesota, for example, markedly raised the professional level of resource

managers of state-owned forests. Wisconsin provided assistance to counties, and Michigan undertook two interrelated initiatives to improve management of its state-forest system. The first initiative involved separating forest uses to reduce unnecessary conflict. The second initiative created a more adequate, investment-oriented funding arrangement for forest management in that part of the state system where intensive vegetation management was the primary purpose.

State and county forests often have an economic-development focus and thus have proved to be especially important to local and regional communities. Commodity outputs tend to be emphasized more strongly the closer management is to the local level. This is perhaps most clearly the case in the Great Lake states. For example, in Michigan during the past 14 to 16 years, the governor's Target Industry Program fostered expansion of forest-products industries as part of a comprehensive initiative to diversify a vulnerable, recession-prone economy. To accomplish economic development, government programs that foster stability in community income and employment have proven to be especially important, as have programs that enable county and state governments to improve the capacity of management to develop sustainable forests.

Tribal Forests

Tribal forests occupy nearly 16 million acres of land and are managed by more than 200 tribal or related governing units in 23 states. These forests provide a wide variety of goods and services to tribal members and the general public. Significant concern about the status of and level of investment in Native American forests led to the National Indian Forest Resources Act, which directed the Secretary of the Interior to obtain an independent assessment of conditions affecting investments in Native American forests and their management (Indian Forest Management Assessment Team 1993). Among the assessment's four most important findings are (1) the existence of a substantial gap between the ideas that Native Americans envision for their forests and the actual management their forests; (2) a major lag in funding for Native American forests relative to funding for federal and private forests; (3) a lack of coordinated forest-resource planning and management; and (4) ineffective methods for setting and overseeing trust standards for Native American forestry. In response to these findings potential federal actions that would improve conditions for investment were identified, including encouraging the development of tribally defined trust standards that clarify trust oversight; increasing funding and staffing to levels comparable to other forest ownerships; protecting Native American forests via ecosystem management; strengthening application of forest-management practices and forest-enterprise performance; and reinforcing coordinated forest-resource planning and natural-resources inventorying.

|

Box 8-1

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Urban and Community Forests

Owners of urban and community forests range from owners of residential city lots to large publicly owned regional parks that urban residents use for recreation. Twenty million acres of land is estimated here to be urban and community forest land. By some estimates, over 60 million acres of urban land in the United States are forested; 75 percent of the nation's population live in such environs (Dwyer et al. 1992). Urban-forest management within the structure of local governments often receives low investment priority. Disinvestment in urban forests occurs; management budgets are reduced and eliminated, and tree care and maintenance activities are done only when reactionary. In California, where municipal-urban forest management has been eliminated in many cities, a number of volunteer organizations are filling the need. Nationally, volunteer organizations dedicated to tree planting and education are forming consortiums to identify how they can continue to participate in urban-forest activities. Although these organizations raise the awareness of thousands of individuals about trees and urban forests and assist urban-forest managers in their educational initiatives, their numbers are still very few.

The National Urban and Community Forest Advisory Council was charged, in part, with determining why investment in urban and community forestry is far less than the benefits often ascribed to these forests. The resulting analysis confirmed a number of disturbing trends (National Urban and Community Forestry

Advisory Council 1993). For example, only one tree is planted for every four removed; 500 to 700 million tree-planting spaces remain vacant; because of improper planting and care, trees in urban areas live only an average of 7 years; compacted and paved-over soils increase temperatures and increase storm-water runoff, which prevents water from reaching tree roots; thousands of acres of forestland are cleared for development with little regard to replacement, further increasing fragmentation of forestlands.

The Council identified two major causes of these disturbing trends: the lack of a comprehensive national program on urban and community forestry, and the marked decline in the health and vigor of most urban and community forests (National Urban and Community Forestry Advisory Council 1993). Six strategies were recommended as means of improving the level of investment in these forests, namely expand public outreach to improve understanding of and appreciation for urban and community forests; foster self-sustaining municipal and community volunteer programs; develop multi-discipline educational opportunities for urban- and community-forestry professionals; stimulate additional funding from public and private sources; support substantial expansion of research on urban and community forests (including distribution of research findings); and promote partnerships with private-sector urban- and community-forestry interests. Also identified was the lack of timely and relevant information about urban and community forests (International Society of Arboriculture 1991).

Investment Issue Areas

Forestland Area

One measure of investments by private concerns is their willingness to own forestland. In fact, most investments in nonfederal forests are made by owners in the form of holding land. The area of nonfederal forests increased from 1987 through 1992 by approximately 3 million acres (Table A-1). However, that increase masks some important regional shifts, most notably declines in the Rocky Mountain region and a large (nearly 7 million acres) increase in the South Central region (Table A-2). Net losses of timberland to agricultural uses in the Southern region are no longer being observed (Powell et al. 1993), indicating that a balance has been achieved in profitability of forestry and agriculture. In the Pacific Northwest region, research has indicated that the proportion of land in forest use should be relatively unresponsive to markets or public-policy instruments, such as cost-share programs (Parks and Murray 1994). As for future ownership, the area of nonfederal forestland is forecast to decline five percent by 2020 and seven percent by 2040. Those declines amount to a disinvestment in nonfederal forest use in favor of other uses. In the federal government's Conservation Reserve Program, trees were planted in a substantial area of highly erodible cropland. That project amounted to an investment in forest and a disinvestment in cropland.

However, the federal program is unlikely to result in a substantial increase in forest area in the near future (Moulton et al. 1996).

Timber Inventory

Another overall measure of investment in nonfederal forests is the volume of growing stock. The overall stock of trees grown on industrial and nonindustrial private forestland has been increasing and is expected to increase (2.5 percent by 2040) (Table A-21). For those ownership categories, softwood inventories are expected to rise by 21 billion cubic feet (in 2040) or about a 10 percent increase relative to 1991 levels (Haynes et al. 1995). Although the overall trend in the average number of trees per acre is up, that average masks some important changes, including changes in species composition and in the resulting character and quality of the forests. Nevertheless, a significant overall increase appears to have occurred in the wood volume of forest trees in recent decades and, thus, in the amount of capital invested in nonfederal forests.

Nonindustrial Private Forests

Nonindustrial private forestlands account for 32 percent of the nation's softwood inventory and 72 percent of the hardwood inventory (Table A-21). Currently, growth exceeds removal of trees for these forests, indicating an increased investment in timber inventories. The overall ratio of growth to removals is 1.5, but the ratio of growth to removals is much lower for softwoods (1.1) than for hardwoods (2.0). As a result, the quantity of the hardwood resource on nonfederal forests has been improving steadily (Powell et al. 1993), but the adequacy of investments in softwoods has been questioned (Cubbage et al. 1995). Projections on nonindustrial forestlands show a sustained increase in softwood inventories over the next 40 years. The current high ratio of growth to removals of hardwoods on nonindustrial forestlands is not expected to be sustained.

Industrial Timberlands

Industrially owned forests are an important part of the nonfederal forest landscape. Investments in these forests vary from firm to firm, depending on the strategic position of timberland in the companies' operations. Industrial firms account for approximately 16 percent of the nation's softwood inventory and 10 percent of the hardwood inventory (Table A-21). The ratio of growth to removals (0.8) on these forestlands indicates an ongoing disinvestment in both hardwood and softwood growing stock. From 1952 through 1987, a 33 percent decline in

softwood growing stock occurred on industrial timberland in the Pacific Northwest (USDA Forest Service 1989). Softwood sawtimber inventories on industrial lands in the Pacific Northwest show a larger and more sustained decline, having dropped by 52 percent between 1952 and 1992 (namely, 236 billion board feet to 114 billion board feet) (Powell 1993). Softwood inventories on industrial forestlands in the South increased from 1952 to 1987, but 1992 statistics showed a reversal of this trend.

Long-term projections of inventories on industrial forestlands show softwood inventories declining in the current decade and then rising through the first four decades of the next century. Long-term hardwood inventories on industrial and nonindustrial forestlands are expected to be close to current levels (Haynes et al. 1995).

Nonfederal Public Forests

Public forestland other than the national forests accounts for 11 percent of the nation's softwood inventory and 10 percent of the hardwood inventory. The trend for several decades has reflected an increase in hardwood inventories and decrease in softwood inventories on these lands (Powell et al. 1993).

Timber Management

Management practices that increase the productivity of nonfederal forests for timber purposes are numerous. Tree planting, for example, is a highly visible, fundamental investment in forestland. In 1995, private landowners planted approximately 1 million acres of trees, which amounted to 85 percent of all planting activity in the nation (Table A-6). Planting by industrial wood-based firms accounted for half of all private planting (1,037,356 acres; 43 percent of total planting in the United States) (Table A-6). On the basis of the 1990-94 annual average of 1,098,000 acres, the trend in industrial tree planting can be characterized as stable to modestly declining, (peak years were 1990 and 1991) (Moulton et al. 1996). Perhaps the timing of industrial plantings was largely determined by the need to replace harvested stands. Industrial owners other than forest-products companies planted 54,654 acres of trees in fiscal year 1995, a significant increase over 1994 (9,356 acres). Those plantings resulted from investments by insurance companies and investment trusts (Moulton et al. 1996).

Another indicator of direct investments in industrial timberland is net annual growth of growing stock per acre, which in 1992 was 61 cubic feet per acre of industrial timberland. Such high growth reflects the physical potential of land to grow timber, but also reflects investments in the modern timber-management practices of controlled spacing, genetically improved trees, and application of

fertilizers. Additional economic opportunities exist for investing (yielding at least a four percent rate of return) in reforestation and controlled-spacing activities on industrial land (Ellefson and Stone 1984).

Information about private investments (exclusive of public subsidies) of owners of nonindustrial forests is scarce. In 1995, private owners planted 956,953 acres of trees, a decrease of about nine percent from fiscal year 1994 (Table A-6). If the tree planting of 419,448 acres with federal-assistance programs is deducted, net tree planting on nonindustrial private forest acres in 1995 was 537,505 acres (Moulton et al. 1996). As with industrial forests, growth per acre is also an indication of nonindustrial private owner investments in forest-management practices. In 1991, the growth per acre was 42, which was close to the national average of 44. On nonindustrial forests, the USDA cost-share programs have contributed to tree planting on one-third to one-half of the acres planted annually over the last four decades. Tree planting on private forestland by the USDA Conservation Reserve Program peaked in the 1980s at over 3 million acres (Moulton et al. 1996).

Investments in planting are often characterized as risky because of the long period between reforestation and harvest. It is not surprising, therefore, that some studies attest to the economic superiority of high-cost planting regimens that involve intensive site preparation (for example, Brodie et al. 1987, Guldin and Guldin 1990), and other studies indicate that low-cost regeneration methods are economically attractive especially for nonindustrial forest landowners for whom a multispecies forest has nonmarket benefits (Haight 1993).

The findings conflict regarding the effect of timber prices on tree-planting activity on private forestlands. Most studies indicate that tree-planting activity in the short run is relatively unresponsive to timber prices but is responsive to costs (Alig et al. 1990); in the long run, responsiveness to timber prices might be much greater (Wear and Newman 1991).

Studies have also concluded that cost-share programs encourage tree planting on nonindustrial forest-lands, although the degree of cost sharing needed to elicit a response from different categories of landowners has not been extensively investigated (Alig et al. 1990).

Investments in timber-management activities other than reforestation are made on nonfederal forests. For example, in 1995, 70 percent of timber stand improvement (TSI) was done on industrial forestland and 18 percent was done on nonindustrial forest-land. The West and South dominate TSI activities, accounting for 69 and 26 percent respectively. Of the more than 3 million acres treated, federal cost-share programs contributed to TSI on only 100,000 acres (Moulton et al. 1996). Research results on the propensity of nonindustrial forest landowners to invest in intermediate stand treatments point to landowner characteristics being more important than expected returns (Alig et al. 1990).

Private Investments

Scale of Private Investments

Trees constitute the bulk of nonindustrial landowners' investments in forestry. Most of their investments are made without government assistance. Investments made to improve the condition of their forestlands are small by comparison, but those investments are important in pursuing particular management objectives. Among industrial landowners, forestlands clearly constitute the bulk of their investments in forestry. The importance of forestlands to individual firms varies according to their function in the firm's operations. In the early 1980s, the value of standing timber owned by 40 companies was estimated to be $47 billion; the top five companies accounted for 46 percent of the timber owned (Ellefson and Stone 1984).

Research on investment and productivity found positive net investment in acreage and management activity on industrial forestlands in the South between 1962 and 1985 but net disinvestment on nonindustrial forestlands (Wear 1994). Long-run forecasts of the timber supply foresee greater management activity on industrial forestlands, but only small increases in management activity on nonindustrial forestlands (Haynes et al. 1995).

Capital and Rates of Return

Acquiring financial resources to manage and protect nonfederal forests adequately is often adversely affected by features specific to forests and forestry. Although low timber prices may be the fundamental cause, two especially widely cited barriers to private investment are lack of sufficient advance capital and low expected rates of return (Haines 1995). In addition, biological risks are often associated with forests (for example, insects, disease, and wildfire), investment returns are not realized for long periods of time, markets are uncertain for some forest-based goods and services, access to capital needed for incremental investments in management is small, small-scale landholdings suffer from large-scale poor economies, and costs for certain positive investments, such as prevention of water pollutants, cannot be recovered. All of these conditions can be encapsulated in the owners' beliefs that forestry investment generally represents slow, modest yield and low liquidity (USDA Forest Service 1989a). For example, in timber-production, financing is required to prepare management plans and establish timber stands, management costs must be covered until first income is received, and reforestation cost must be paid. These special features of forests and forestry can make investments in them unattractive to private investors and call for ways to reduce risk, increase efficiency, and reduce cash-flow problems (McGaughey and Gregersen 1988). Limitations on nonindustrial private forest landowners' access to capital markets are also a concern. Evidence from studies

in Finland suggests that the perception of credit rationing affects landowner management behavior (Kuuluvainen and Salo 1991).

Regulatory Effects

A variety of local, state, and federal programs require forest landowners to limit disturbances of wildlife in critical habitat areas, reserve riparian areas to enhance water quality and fish habitat, submit professionally prepared management plans for regulatory approval, and reforest harvested stands to ensure future timber supplies. The investments mandated under these programs are unpopular with many landowners and have been criticized for diverting funds from other investment opportunities.

In general, however, the effect of public regulatory programs on nonfederal forests has been to increase tree planting, improve water quality, and protect wildlife habitats. Whether these results would have been greater under a different type of public program (for example, cost-share or technical assistance) is not known. Analyses showed that in Oregon, Washington, and California, for example, 30 to 40 percent, 10 percent, and 25 percent more area, respectively, was reforested since the inception of each state's forest practice regulatory law. In California, regulations resulted in $2 to $3 million of reforestation that would not have occurred otherwise (Ellefson et al. 1995). Other assessments have shown that current and expected state regulatory programs would often substantially increase private timber inventories over base (or expected) inventories, with harvest volumes remaining the same or slightly different from base levels (Haynes et al. 1995). Regulatory effects appear to have been greater on softwood resources than on hardwood resources, based mostly on western public timberland withdrawals. However, in the East, regulatory actions are more likely to decrease hardwood timber availability (Greene and Siegel 1994). In addition to the unpopularity of regulatory programs, diversion of funds from other investment opportunities (for example, plant modernization) is also a real concern. Regardless of effects, controversy remains over the long-term effects on forestry investments and whether cost-sharing programs should be considered replacement or expansionary investments (Alig et al. 1990, Lee and Kaiser 1992, Wear 1993, Haynes et al. 1995, Haines 1995).

Public Investments

Although many landowners do not consider government assistance necessary for them to make appropriate investments on their land, others argue strongly for the necessity of publicly funded cost-sharing programs to overcome the deterrents to private investment. This lack of consensus is understandable given the

diversity of nonindustrial private forest landowners, and the difficulty of defining what constitutes optimal, appropriate, or adequate investment. However, public investments in protection as well as education, technical, and financial assistance programs are effective at the margin in increasing the willingness of landowners to invest further in their forest properties.

Federal Investments

Considerable research and public debate has focused on the question of whether the cost of public investments in nonfederal forests are commensurate with the benefits contributed by such forests nationwide. The data for making such judgments are sketchy, although information is available on federal expenditures by program category for assistance to nonfederal-forest owners (see Tables A-23, A-24, A-25, and A-26). Whether these investments are sufficient is subject to conjecture. Focused investment opportunities for public monies do exist. In the late 1980s nationwide, nearly 70 million acres of private forestland (excluding industrial timberland) could be regenerated or subjected to stocking-control practices for at least a four percent return rate on the investment. The total cost of carrying out these treatments is approximately $7.2 billion, the largest share of which would be invested in the South Central and Southeast regions (USDA Forest Service 1989a). Another study suggested that investment opportunities of at least four percent (again, mostly in the South) existed in the late 1980s on 50 million acres of nonindustrial private forestland (USDA Forest Service 1988b,c). Although the information available to make these investment decisions is sketchy, economically attractive investments could be made that are not being made in the current investment climate.

Concern for the adequacy of federal involvement in the future is especially apparent in the concern for tree planting after the decline of the federal Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). Tree planting in the United States was expected to decline after the CRP, and that decline has occurred. Most CRP tree planting, 2.2 million acres, was done in 1986-1989; an additional 396,000 acres were planted from 1990 to 1997. When CRP plantings are deducted, tree planting for all ownership categories has remained essentially constant (2.4 to 2.5 million acres) since 1983 (for 12 years). Because the bulk of CRP planting have been done in the South (more than 90 percent) and on nonindustrial private forests, the implications of reduced CRP planting are especially critical for that region and for those nonindustrial forest owners. Concern over future timber supplies is increasing because of the scarcity of timber resources in the South and the reluctance of nonindustrial private landowners to plant trees in response to higher stumpage prices (Alig et al. 1990, Cubbage et al. 1995). The decline in CRP planting of pine plantations (especially loblolly pine) also has serious negative implications for various species of wildlife, especially birds and small mammals (Moulton et al. 1991).

State and Municipal Investments

States invest in private forest-lands by providing protection from wildfire, insects, and disease and also by providing technical and financial assistance to private owners. In addition, states and municipalities are themselves forest landowners, with objectives and investment behaviors that vary as widely as those of industrial or nonindustrial forest landowners (Souder and Fairfax 1995). Little information is available on trends in investments on these lands. For the period for which data are available (1978-1987), state funding of forestry programs increased substantially in nominal-dollar terms, although in real terms state revenue decreased somewhat or, at best, remained stable (Table A-25).

States with the most rapid increases in forestry budgets were in the South, Midwest, and Mountain regions; those with the most rapid decreases were in the Northeast and the West Coast. The differences largely reflect the general economic climate of the region. Although real-dollar state forestry budgets (excluding federal funds) were stable or slightly reduced, they increasingly accounted for less of the states' natural-resource budget (which increased 20 percent from 1978 to 1987 real dollars) and less of the state budgets generally (Lickwar et al. 1988). Evidence also suggests that state forestry agencies that are part of a larger environmental regulatory administration have had substantially reduced budget allocations (Hacker and Ellefson 1996).

Scale of Public Investments

Public investments in cost-share programs and technical assistance are important, yet they are quite modest to many. Whether the amount of public investment in such programs is sufficient to be effective is questionable. For example, the federal Forestry Incentive Program enabled reforestation of 2,789,000 acres from 1975 to 1993 (at a federal cost share of nearly $156 million) or 155,00 acres per year (Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service 1993). However, in 1987, an economic opportunity developed (treatment yielding four percent or more) to have 47 million acres of nonindustrial private forest regenerated (USDA Forest Service 1989). Similarly, the Stewardship Incentives Program in 1992 assisted 579 persons in developing stewardship incentive plans covering 89,541 acres at a federal cost share of $293,000 (Agricultural Stabilization and Conservation Service 1993). The number of persons involved in these programs is small in comparison to the 9.9 million nonindustrial forest owners who own 353 million acres of forest in the United States. At a rate of new plans covering 89,000 acres of forest each year, it will take many decades to have plans covering even a small portion of the nation's nonindustrial private forestland. The programs used as examples here are not the only federal cost-share programs devoted to private forestry. The size of the federal effort is larger than that but

certainly is not excessive. The concerns over federal assistance are not about program efficiency but about appropriate scale and whether existing programs are large enough to make a difference. Also enlightening is the rate of federal investment per acre in nonindustrial private timberland via USDA Forest Service state and private programs versus the agency investment in national forest timberland. The latter is approximately $30 per acre while the former is about $0.50 per acre.

Infrastructure Investments

To produce goods and services, the nation's nonfederal forests require substantial investments in the infrastructure, including bridges, buildings, trails, campgrounds, communication systems, and flood-control structures. From 1970 through 1990, national nonmilitary capital stock declined over 8 percent as a proportion of gross national product, and new public capital investments nearly stopped in the mid-1980s. The implications of those declines can have serious consequences for nonfederal forests: (1) a less useful and less modern infrastructure will be available for the management of nonfederal forests and the delivery of goods and services from such forests; and (2) communications will be less socially and economically healthy within or near nonfederal forests because of the low rates of investment in schools, transportation systems, and hospitals (Lewis and Ellefson 1993). Infrastructure investments are frequently large, leading many to call for the federal government to share their costs or at least to create an economic environment in which other units of government and the private sector can make the infrastructure investments needed for effective management of the nation's nonfederal forests.

Incidence of Investments

Opportunities for furthering the magnitude and kinds of benefits generated by nonfederal forested lands certainly exist and possibly are facilitated by public investments. Some observers argue that investments in private forest properties are the sole responsibility of private owners and that the government has no role to play. Others suggest that private investments result in a variety of public benefits; therefore, the public should bear a portion of the costs of producing these benefits. For example, better water quality or more pleasing landscapes are enjoyed by a wide segment of the public. Some inequality geographically or temporally between those who pay for and those who benefit from investments in nonfederal forests is, perhaps, inevitable. However, investment responsibilities should be allocated to the extent possible to minimize unfair distribution.

Potential Strategies

Remedies for Investment Disadvantages

Attracting investments in nonfederal forests can be facilitated by making the climate for private and public investments more attractive economically, and by improving access to adequate sources of financing. Steps can be taken to generate greater interest in investing in nonfederal forests by focusing on remedies for the apparent investment disadvantages that forests generally exhibit. Among the potential remedies are cost-share programs, access to credit, special tax treatments or exemptions, and efficient timber-producing operations. A clearer link between the forestland investors and the beneficiaries of such investments has also been suggested as a way to enhance investment opportunities. Payments from hydroelectric power concerns, users of irrigation water, and users of domestic and industrial water for upstream forest-management activities could clarify the link (McGaughey and Gregersen 1988).

Reducing risk and uncertainty can also improve the investment climate for nonfederal forests. Among the options to do so are expanded protection programs; guaranteed prices for timber products, insurance programs to protect against catastrophic losses; and greater access to marketing information, price reporting, and technical assistance (Boyd and Hyde 1989). The public role in providing technical assistance, however, might be reduced in the future because of the development of efficient markets for technical assistance (Munn and Rucker 1994, McColly 1996). Public technical assistance has been found to be less effective than cost-share programs in promoting reforestation investments (Skinner et al. 1990). On the other hand, only one in five nonindustrial private forest landowners has a written management plan for their forestland, and only 11 percent of those plans were prepared by consultants (Birch 1996). Other studies of technical-assistance programs have concluded that public and private assistance are effective and efficient (Cubbage et al. 1996).

Options to overcome the problem of insufficient cash flow during the life of forestry investments include access to loans and easily accessible credit sources (Rhinehart 1992), lease arrangements for timber productions, and formation of cooperatives that pay annual fees to landowners in anticipation of access to timber. Improvements in the investment climate for nonfederal forests also implies changes in allowable tax deductions for reforestation and management costs, changes in the effective tax rate for capital gains, providing tax credits for industrial assistance to nonindustrial forest landowners, and providing favorable property tax laws for forestland. Unfortunately, the basis for judging the desirability of such changes in the tax laws is often inadequate, except with respect to the obvious desirability of a stable environment in which investment decisions can be made (Boyd and Hyde 1989, Chang 1996).

Sources of Capital for Investments

Public-sector funds for investments in nonfederal forests have traditionally come from public borrowing or from a wide variety of tax levies on incomes (income tax and value added tax), wealth (property, death, and gift), and consumption (sales tax and excise tax). In the current political climate, interest in looking beyond traditional investment sources has grown. Half of the states with rising state forestry budgets from 1978 to 1988 reported increases in funding from nontraditional sources (Lickwar et al. 1988). In some cases, the sources provided revenues specifically dedicated to forest and natural-resource activities. For example, Wisconsin's mill tax dedicates a portion of state property taxes to support the Wisconsin Bureau of Forestry, and an Oregon severance tax on harvested timber supports programs in the Oregon Department of Forestry. Natural-resource programs in Missouri and North Carolina are partially supported by a dedicated portion of general state sales taxes. To dedicate funds for activities on nonfederal forests requires a good match between revenue sources and revenue needs; a simple administrative mechanism for gathering and managing the funds; protection of general fund monies, especially if dedicated funds perform well; and prevention of diverting dedicated funds to nontargeted programs (Hacker and Baughman 1995). Especially innovative funding mechanisms using general obligation bonding have been used in Florida and Michigan to secure funding for activities that will later provide revenue to pay off the bonds (Box 8-2).

Financing for industrial forestland investments comes from retained earnings, borrowed money, and sale of equity. On nonindustrial forestlands, financing of forestry activities comes from savings, grants, and borrowing. Especially innovative funding mechanisms for private financing of activities on private forestlands include Norway's Forest Trust Fund (Oistad et al. 1992) and Oregon's Forest Resource Trust Fund (Box 8-3, Box 8-4). Both programs involve a portion of receipts from the sale of products to be deposited in a fund that can then be invested in forest-management and protection activities.

Summary of Findings and Recommendations

Investments in forestland and the trees account for the bulk of the nation's investments in nonfederal forests, which serve many purposes. These purposes range from timber production, to provisions for recreation and aesthetic values, to providing habitat for endangered species. Holding land and trees may not serve all purposes equally well; however, investments are being made in both forestland and trees by individuals to meet most objectives of sustainable management of nonfederal forests. Critical to these investments in nonfederal forests are healthy national and regional economies in which the federal government has a major role.

Most investments in nonfederal forests are made by private forest owners. The size of the investments made by the owners (or the public) to improve the

|

Box 8-2

|

||||||||||||||||

|

Box 8-3 Authority and Purpose: Norway's Forest Trust Fund was authorized by the Norwegian Forestry and Forest Protection Act of 1965 (Fund established by law in 1932). The purpose of the Fund is to promote timber production, reforestation, and protection of forests while encouraging their use and management for recreation, wildlife, quality water, and scenic beauty. These intents are to be accomplished by balancing private landowner freedom and responsibility. Requirements: All private forest landowners selling timber from their land must place 5 to 25 percent of the gross value of timber sold into trust account. Exact amount depends on the landowner's tax and financial status and on past history of caring for forest (current average rate is 12 percent). Buyer of timber deducts correct percentage from sales receipt and deposits said amount in the seller's (landowners) account at a local bank providing the most favorable interest rate. Landowners may withdraw funds from their trust account for purposes of carrying out forestry practices on properties from which the money originated. Acceptable practices are determined by landowner associations and the Norwegian Department of Forestry. Because landowners do not receive the interest earned by their trust fund accounts, they have a strong incentive to quickly withdraw the funds and invest them in forestry practices that will provide a financial return. Tax implications: Landowners may deduct from federal income taxes the full amount of their deposit into a trust account. When the funds are withdrawn and applied to a forestry practice, a significant portion of such investments can also be deducted from annual income taxes. Depending on the owners marginal tax rate, these incentives amount to public subsidies of 50 to 60 percent of the cost of the practice. Public Purposes: Interest from landowners' trust accounts is used for the common benefit of forestry at local, regional, and national levels in Norway. With its portion of the funds, Norway's Department of Forestry supports forest nurseries, seed orchards, professional continuing education, and publicly-oriented organizations such as a forestry museum, professional forestry society, and an extension service institute. Local governments support demonstration projects, study tours for public, planning activities, and equipment rental. Magnitude of Program: In 1988, landowners withdrew $48 million from the Trust Fund. In 1989, the Fund contained approximately $84 million, of which $54 million was deposited by landowners in same year. Source: Oistad et al. 1992. |

|

Box 8-4 Authority and Intent: The Forest Resource Trust was established in the Oregon Department of Forestry by state law in 1993. Its purpose is to provide funds for financial, technical, and related assistance to nonindustrial private forestland owners for stand establishment and management for timber, wildlife, water quality, and other purposes. Priority given to reforestation of lands zoned for forest uses and other lands with high probability of successful reforestation. Goal is to reforest 250,000 acres by 2010. Administration: The Trust Fund is created in the State Treasury, separate and distinct from the General Fund. Earnings on money in Trust are retained in fund. Overall responsibility for the Trust rests with the State Board of Forestry, although a 15 person advisory committee assists the Board in setting policy for the program. The State Forester is responsible for implementation of the program, including identification of suitable lands, providing technical assistance, and monitoring landowner compliance with agreements involving the Trust. A biannual report on program status must be submitted to legislature, as well as an independent evaluation of program goals, administration, problems, and outcomes. Eligibility: Eligible persons are nonindustrial private forest landowners having land that is: deemed capable of supporting a healthy stand of trees; at least 10 acres, but not over 5,000 acres in size; zoned for forest or farm use; free from reforestation requirements of the Oregon Forest Practices Act; free from any covenants or encumbrances prohibiting tree cutting; and not under petition for conversion to non-forest property. Application: Qualified landowners must develop a project plan, often with the assistance of a consulting forester, extension forester, or Department service forester. Plan must include maps, aerial photos, recommended forest practices, and implementation time schedule. Approved plans receive up to 100 percent of cost of implementation. Maximum of $100,000 every two years per landowner. Obligations: The landowner is obligated to repay the loan (return to the Trust) from proceeds of the sale at the time of harvest (a lien imposed on timber to be harvested). The obligation runs with the property, unless terminated when the forest is destroyed through no fault of the landowner (e.g., insects, disease, fires, flood), or repayment of the loan (including interest) by an owner during the 200 year life of the contract. The landowner chooses when and whether to harvest, but must notify the Oregon Department of Forestry of intent to harvest. The landowner must agree to allow access to the land by the state forester. Magnitude of Program: In 1995, landowners borrowed $500,000 from the Trust, namely the total amount contained in the Trust in that year. Source: Oregon Department of Forestry 1996 |

condition of nonfederal forests is minimal in comparison with the simple costs of holding the land and trees. Economic opportunities for larger public and private investments in nonfederal lands do exist. State governments make substantial investments in nonfederal forests, although their investments are declining in proportion to state natural-resource budgets and state budgets generally. Regulatory programs in some states require private investments in forest management, an approach that has serious political and investment ramifications. Relative to the opportunities for investment in nonfederal forests, federal investments in cost-share and technical-assistance programs are modest.

Nonfederal forests and the communities associated with them suffer from a lack of investment in various types of infrastructure. In addition, forests and forestry often exhibit special conditions that can discourage investment in nonfederal forests. Some private owners of nonfederal forest-land in certain regions of the nation are no longer investing in certain types of timber growing stock, especially softwoods in the Pacific Northwest. Among the disadvantages to owning forestland are high risk, long time periods before returns are realized, and uncertain markets.

Investments made in nonfederal forests by various segments of the public should be commensurate with expected returns to the public. In many cases, that means that funding of public programs for nonfederal forests should be increased. Infrastructure conditions needed to provide a wide range of benefits from nonfederal-forest development should be assessed, and additional public investments in infrastructure should be made as needed.

For purposes of attracting additional capital, public actions should be taken to reduce the risk and uncertainty that often deters long-term investments in nonfederal forests. Federal and state governments should ensure especially that tax policies do not deter investment of private capital in nonfederal forests. The tax policies should be neutral in application, equitable among sectors, and efficient in cost of collection. The federal government could provide more information on private and public financing of nonfederal-forestry programs and assist financing states in implementing especially effective financing programs that are used in other states or other countries.

Recommendation:

Promote public and private investments in nonfederal forests by establishing innovative investment policies and fostering healthy national and regional economies. Investment should be broadly construed to include financial, intellectual, human and ecological resources.

This points to the following specific recommendations:

- Major deterrents to private investments in forestry that affect investment by nonindustrial private landowners, especially lack of sufficient advance capital and low expected rates of return, should be eliminated.

- Federal fiscal and technical assistance programs leading to investments in private nonfederal forests should be sufficiently large to affect the use and management of nonfederal forests.

- Innovative public and private revenue sources for investments in nonfederal forests, including general obligation bonds and various forms of private trusts, should be established.