3—

Forest Values and Benefits

Introduction

Nonfederal forests provide a wide variety of benefits that are important to the sustainability of the nation's economies, communities, and natural environments. For example, nonfederal owners of forests often benefit directly from the income they receive from forests and from the pleasure they experience when using and managing their forests. In a broader context, society may be the recipient of benefits provided by nonfederal forests, namely income and employment for its citizens and opportunities for them to exercise their interests in leisure and recreational activities. Obtaining these and many other benefits depends on the nation's willingness to invest in the sustainable management of nonfederal forests. A brief description of the many benefits provided by these forests is presented in this chapter.

Employment and Income

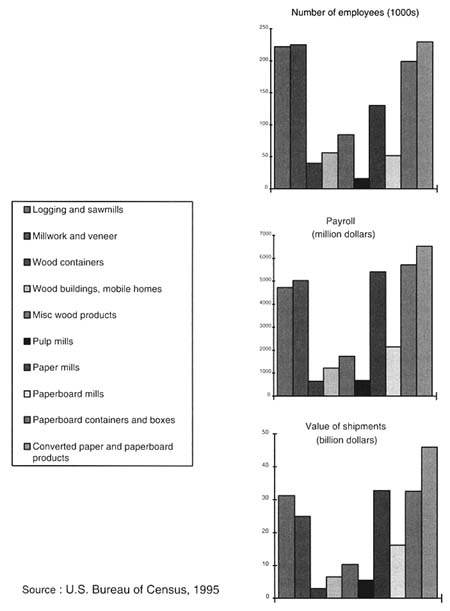

Forests are sources of employment and income for the nation's citizens. However, with the exception of data on Native American forests, there is little information that directly links these benefits to nonfederal forests on a national scale. For all forest ownerships in the United States, the U.S. Bureau of the Census estimates that nearly 1.3 million people were employed by U.S. wood-based industries in 1992 (GAO 1992) (Table A-18, Figure 3-1). The total payroll received by these employees was $33.9 billion, while the value of shipments made by the industries was estimated to be $209 billion. The American Forest and Paper Association (1995b) also has estimated the economic importance of

the nation's wood-based industries. In 1990, they employed more than 1.6 million people, of whom 59,100 worked in forestry, 701,800 in the paper industry, and 852,200 in the lumber industry.

Tribal forests are a source of considerable economic wealth for Native Americans. In 1991, these forests and associated programs provided more than 3,000 full-time and 28,000 part-time jobs for Native Americans. The Intertribal Timber Council (1993) estimated that economic benefits accruing from tribal forests were more than $284 million to Native Americans and an additional $180 million to nonNative Americans. Most of these economic benefits result from the harvesting of timber—nearly 810 million board-feet of timber in 1990—on tribal lands. Fuelwood, pinyon nuts, range forage, and other products also have provided a substantial portion ($38 million annually) of the economic benefits provided by tribal forests (Intertribal Timber Council 1993).

The public sector is also an important source of employment for citizens. For example, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service had 31,135 permanent and excepted conditional employees on its payroll as of September 30, 1995. When seasonal and other types of employees are added, total USDA Forest Service employment in that year was the equivalent of full-time employment for 38,330 individuals (USDA Forest Service 1996b). Information from the National Association of State Foresters indicates that in 1994 the state forestry agencies in the 50 states plus the District of Columbia and Guam employed 16,865 permanent employees. This total includes managerial, professional, technical, and clerical employees. Another 7,680 seasonal and temporary employees were employed by these state agencies in 1994. Other forest-related employment can be found within counties, municipalities, private consulting firms, colleges and universities, and nonprofit organizations.

Timber and Wood Products

Timber and wood products are major contributors to the high quality of life experienced by the nation's citizens. More often than not, these materials come from nonfederal forests. In 1991, the softwood and hardwood timber harvest in the United States exceeded 16.3 billion cubic feet (Tables A-19, A-20, A-21, and A-22). Of this total, 82 percent (13.4 million cubic feet) originated from industrial and nonindustrial private forestland. Timber harvested from city, state, or county land would increase this amount. [Estimates of timber harvest commonly are made available for four major ownership categories: national forest, other public forest, forest industry, and farm and other private forest. The ''other public forest" category is a diverse group of federal (for example, Bureau of Land Management, and Department of Defense) and nonfederal public (for example, city, county, and state) land management agencies. A breakdown of timber supply and demand information for the nonfederal public portion of this category is not readily available from existing sources.] If timber taken from this land is

included, harvests from nonfederal forests would likely be in the range of 13.7 to 14.0 billion cubic feet. Since 1952, timber harvested from forest industry and farm and other privately owned forestland has decreased from 86 to 83 percent of the nation's total. More recently (1986–1991), the proportion has increased, primarily as a result of increased harvesting on industrial forestlands (USDA Forest Service 1995a).

Nationwide harvest of timber is expected to increase from slightly more than 16 billion cubic feet in 1991 to nearly 22 billion cubic feet in 2040 (Table A-19). Timber harvest from nonfederal forests is expected to rise through 2040 by 47 percent over 1991 levels, an additional 6.3 billion cubic feet of harvested wood. Expected declines in harvest from national forests and other public ownerships will temper the overall increase in harvest from all ownerships. More than 80 percent of the increase in harvest from nonfederal forests (5.0 billion cubic feet) will originate from nonindustrial private forests. Softwood timber harvest from industrial forests is expected to steadily increase as industrial softwood inventories increase through 2040.

Regional shifts in harvested timber volumes are likely to occur during the next four decades. (Table A-20). By the year 2020, the Southern United States, a region with a large proportion of the nation's nonfederal forests, will produce more than half of the nation's harvested timber volume. Southern timber harvest is expected to rise sharply in response to harvest reductions on Western public lands. Of special concern is the anticipated temporary reduction in harvestable acres on nonindustrial private forests between 2000 and 2010—the result of sharply reduced planting and accelerated loss of nonindustrial forestland to nonforest uses in the 1970s; this activity did not occur on Southern industrial forestlands. Because of the age structure of industrial forests in the South, these forests will not augment the expected reduced harvest on nonindustrial private forests. Timber management will become more intense on industrial forestlands, with the intent of reducing delays in stand regeneration and increasing tree growth once stands are established. This activity will accelerate site occupancy and hasten closure of stand canopies (USDA Forest Service 1995a). As a result of federal timber harvest cutbacks, harvests in the Pacific (Northwest and Southwest) region are projected to decline from 21 percent (1991) to 14 percent (2020) of the nation's total volume harvested. This regional shift is in large part caused by the substantial reductions in harvest that occurred on federal public forestland in the Pacific Northwest and Southwest.

In 1991, growing stock inventories nationwide exceeded 785 billion cubic feet, of which 491 billion cubic feet (62 percent) was situated on nonfederal forest-ownerships (Table A-21). Of the latter, 316 billion cubic feet were held on nonindustrial private forestland.

Nearly 70 percent of industrial growing stock is softwood, and more than 60 percent of nonindustrial growing stock is hardwood. Growing-stock inventories (hardwoods and softwoods) are projected to increase by 21 percent (165 billion

cubic feet) nationwide between 1991 and 2040 (Table A-21). Forest-industry softwood inventories are expected to decline between 1991 and 2000 but increase by nearly 47 percent between 2000 and 2040. In contrast, softwood inventories on nonindustrial private lands will fluctuate minimally between 1991 and 2040 because of an approximate balance between timber removal and growth. The trend for private hardwood inventories is unclear; however, industrial and nonindustrial hardwood inventories are anticipated to be lower in 2040 than in 1991. On industrial and nonindustrial lands, inventories will be concentrated in timber ages near or below minimal merchantable limits. Although regional variations will occur, private forests will be younger and, on average, smaller in diameter than in the past. In addition, (USDA Forest Service 1995a).

Nonfederal forests accounted for more than 75 percent of the nation's net annual growth of growing stock in 1991 (Table A-22). Of the nonfederal portion (16 billion cubic feet), one-quarter was held on industrial forestlands. In general, hardwood net annual growth is expected to decline and softwood growth to rise through 2040 on industrial and nonindustrial forestland.

Growth and inventory trends on nonfederal forests are likely to have important impacts on water quality, wildlife populations, and recreation values. For example, on private lands, habitat will shift to favor species that can use early-and mid-successional stages of forest development; on public nonfederal forestlands, mid-to-late successional habitat will become more abundant.

Nontimber Forest Products

Nonfederal forests are also a source of nontimber products, such as pine cones, honey, mushrooms, and maple syrup. Currently, more than 450 special forest products in 18 categories are harvested from American forests (USDA Forest Service 1993). In the Northeast, for example, the gathering of pine cones for seed or decorative purposes is common on private forestland. From state-owned public forestland, Minnesota has sold between $8,000 and $10,000 worth of pine cones annually. Traditional food products (pine nuts, camas, and huckleberries) are gathered by tribal members, wildcrafters (Box 3-1), and recreational visitors on nonfederal forestlands. In 1990, the value of honey production in Florida was an estimated $10 million, most of which is attributable to an apiary in the Apalachicola National Forest near Tallahassee (USDA Forest Service 1993a). Forest industry leases bee rights on substantial portions of the Atlantic Coastal Plain and Flatwoods, providing a significant base of honey production.

In the Pacific Northwest, harvesting of mushrooms is an economically and socially important activity in many nonfederal forests. For example, the Washington Department of Natural Resources leases land to individuals to harvest mushrooms. Mushrooms are currently generating sales over $125 million in the Pacific Northwest, with a work force of over 10,000 people. Little is known about the conditions that produce these fungi, yet harvests continue to increase.

|

Box 3-1 Wildcrafting use of forests is rapidly expanding, particularly in areas where logging on public lands has recently and sharply declined. For example, in northern California, lichens, decorative boughs, burls form the bases of trees, and mushrooms have partially replaced timber as a major regional source of revenue. In Trinity County, an area with about 90 percent Federal forestland, over 50 herbs are now collected and marketed by wildcrafters. While not by any means a complete economic substitute for timber, wildcrafting brings in hundreds of millions of dollars nationally and is growing at about 20 percent per year. Concerns that over-harvesting may place these resources in jeopardy have prompted researchers to begin collaborative work with wildcrafters and local Native American tribes, where much of the historic expertise in using forest products other than timber resides. Source: Adapted from the New York Times 1996 |

Much of the production of maple syrup, including the tapping of trees, is carried out on nonindustrial forestlands, especially those that are privately owned. Nationwide, the value of maple syrup production in 1991 was in excess of $39 million (USDA Forest Service 1993a). Floral greenery is an established special forest product, and forestlands can be managed specifically to encourage favored species and environmental conditions. Basket weaving by Native peoples, such as the basket weavers of California, is another important example of the production of nontimber forest products.

Nontimber forest products are easily identified with particular land parcels or regions of the United States. These products present landowners with commercial opportunities or opportunities to use the activities of gatherers as management tools to manipulate vegetation by species or by product quality. Harvest of special forest products on federal and nonfederal lands is likely to increase. Annual income from visually nonintrusive harvesting of such products is an incentive for nonfederal landowners to be involved.

Urban and Community Benefits

Although urban residents use wildlands beyond city limits, they spend comparatively more time in urban and community forests (Miller 1988). This is especially true for the disabled, the elderly, young, or those who have low incomes. Urban and community forests provide a variety of important social and environmental benefits (Box 3-2), the economic value of which has been estimated to be $3 billion per year nationwide (McPherson and Rowntree 1991).

Urban and community forests moderate climate; protect air quality; control rain runoff; lower noise levels; provide wildlife habitat; improve the aesthetics of

|

Box 3-2 Milwaukee has begun to quantify the costs and benefits of trees in its urban ecosystem. Reductions in storm-water flow, conservation of energy, and improvements in air quality were studied to determine the financial contribution of the tree canopy to the city. An analysis using a Geographic Information System (GIS) indicated that only about 16 percent of Milwaukee has tree canopy cover and of this 80 percent is on private property. This relatively low tree cover, which varies from 1 to 42 percent per ownership unit, can be attributed to human development and Dutch Elm Disease. The existing tree canopy cover reduces storm-water flow by up to 22 percent and provides an estimated $15.4 million in savings. If all the trees in Milwaukee were removed, the additional storm-water would require the construction of an estimated 357,083 cubic feet of water retention capacity. The city's trees also sequester an estimated 1,677 tons of carbon annually, a benefit valued at $1.5 million. By maximizing urban tree canopy cover to match existing well-canopied sites, 4,793 tons of carbon could be sequestered annually. The resulting summer energy savings are estimated to be $650,000. Currently, benefits from trees in urban areas are not derived primarily from marketed products or raw materials but from improvements in temperature and other environmental measures, such as storm-water flow, water quality, energy use, real estate values, pollution control, and health and psychological benefits. Whether they are on publicly or privately owned land, trees in the urban ecosystem provide unique benefits. |

cities; and, in some instances, conserve energy, carbon dioxide, and water. They also provide social benefits, which include medical, psychological, social, and managerial benefits (Schroeder 1991). Medical benefits accrue from reduced stress and general improvement in public health. Psychological benefits result from the improved aesthetics of residential streets and community parks as well as from communities' enhanced sense of social identity and self-esteem, particularly in areas with active community involvement in tree-planting programs (Kaplan 1995a,b).

Urban and community forests also provide benefits that are directly appropriable by landowners, such as the value of timber located near urban areas. For example, in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia approximately 26 percent of the timberland is located in Metropolitan Statistical Areas (DeForest et al. 1991). Landowners also benefit from increases in real estate value, increases that are directly attributable to trees. A conservative estimate is that the value of trees surrounding detached housing units in the United States is the source of an additional $1.5 billion per year in property tax revenue (Dwyer 1991). Various studies also suggest that property owners benefit from energy conserved as a result of properly located and sized trees.

Recreational Opportunities

Nonfederal forests provide citizens with a wide variety of recreational benefits, particularly on public nonfederal forestland. In 1989, an estimated 52.6 million acres of state land was available for recreational use, nearly half of which was managed by state forestry agencies (English et al. 1993). State park and state fish and game agencies managed 19 percent and 31 percent of this area, respectively. Despite their relatively small land base, local governments managed the other half of outdoor recreational use. This is due to the close proximity of recreational public-land sites to people's homes.

Recreational pursuits are also available on private forestland. In the contiguous United States, for example, an estimated 23 percent of nonindustrial private forestland is available for recreational use by the general public (USDA Forest Service 1989). In addition to the 23 percent of nonindustrial private forestland that is accessible by the general public, another 45 percent is open to people personally acquainted with the landowner, and 26 percent is open only to landowners and their immediate families (USDA Forest Service 1989b). The aesthetic values of nonindustrial forestland are also important to landowners and citizens alike (Moulton and Birch 1995). Along major travel corridors, private groups have coordinated efforts to manage forest landscapes in manners that will preserve important scenic amenities.

Fishing and hunting in forested environments provide substantial personal enjoyment to citizens and economic returns to rural communities. Fishing and hunting rights are sold on many nonfederal forestlands. Nonconsumptive uses of forest wildlife are expected to grow twice as fast as the nation's population to 2000, with all forms of cold-water fishing activity to increase at about the same rate as the population (USDA Forest Service 1989, 1994). Citizens are also experiencing benefits from increases in wildlife species that thrive in forest-edge environments (e.g., deer, elk, turkey) (MacCleery 1995). Public lands, including nonfederal public forestlands, are expected to become relatively more important for big-game hunting and cold water fishing, assuming that access remains generally unrestricted and free. Hunting on private forestlands for a fee is also expected to increase (USDA Forest Service 1989, 1994).

Tribal forests are sanctuaries for worship and religious ceremonies and contain burial sites and other culturally significant areas for Native Americans. Forest wildlife contributes to the religious, cultural, and medicinal needs of many tribal members (IFMAT 1993).

Although not necessarily focused on securing recreational benefits, citizens frequently seek to preserve forests, including certain nonfederal forests, as a means of ensuring that future generations will be in a position to make choices about their use, management, and protection. Citizens' general interest in preserving forests that they will probably never lay claim to is an indication that they value these forests and the benefits provided by them.

Ecological Benefits

Nonfederal forests provide a wide variety of ecological services and benefits. For example, they are storehouses of large amounts of carbon. In the continental United States, nonfederal forests store an estimated 38.6 billion metric tons of carbon (90 percent of the national total), and Alaskan forests store an additional 16 billion metric tons. Approximately 90 percent of this continental storage capacity is provided by timberland—55 percent in nonindustrial private forests and 15 percent in industrial forests. Between 1987 and 2000, nonindustrial private timberland is projected to sequester an average of 61 million metric tons of carbon annually in living trees and understory vegetation. Carbon sequestration from removals (for example, wood products) is estimated to be 58 million metric tons annually during the same period-although the fate of carbon stored in these products is unclear (Heath and Birdsey 1996).

Nonfederal forests provide habitat for important threatened and endangered species. Of 712 listed species, 609 (86 percent) have their habitat on private individual or corporate property, much of which is forested. Public nonfederal lands provide habitat to 516 species (72 percent), while nonprofit-owned land and tribal land provide habitat to 181 and 61 species (25 and 9 percent), respectively. Fifty-two species are found on other nonfederal lands (GAO 1994a). Considering all ownerships, forests provide approximately half the habitat for the nation's threatened and endangered species (USDA Forest Service 1994d). More than 90 percent of these listed species have some or all of their habitat on nonfederal lands, although not necessarily on forested lands (GAO 1994a). Nearly three-quarters have at least 60 percent of their habitat on nonfederal lands; 37 percent are completely dependent on nonfederal lands.

Forests are also the source of approximately 60 percent of the nation's total stream flow, the primary means by which high-quality water is provided for industrial, municipal, and recreational uses. As the nation's major forest ownership category, nonfederal forests play an especially important role in this respect. Analyses suggest that precipitation on all types of land currently provides enough surface and ground water (1.4 trillion gallons per day) to meet not only present but also prospective withdrawals: 500 billion gallons—only 10 percent of precipitation—by 2040. However, these estimates mask important regional supply-demand imbalances, which are caused primarily by geographic, seasonal, and annual variations in supplies. These are areas of the nation where ground water development, instream use (e.g., navigation, recreational activities, and hydropower generation) and surface water development (e.g., municipal and industrial uses) are expected to be especially demanding (USDA Forest Service 1988a). In areas where these conditions occur, nonfederal forests will be called upon to play an especially important role in providing quality water in sufficient quantities.

The quality of water flowing from forested land has been of special concern since the early 1970s when federal laws began to emphasize activities to deal

with nonpoint sources of water pollutants. The quality of water flowing from forest and rangelands is good (USDA Forest Service 1993)—in large measure, this is because of federal programs that encourage states to initiate plans and programs for addressing water quality issues. In response to these federal programs, state governments, in cooperation with private concerns, have established a wide variety of water-quality best management practices that are being delivered to landowners and timber harvesters via educational, technical assistance, financial, and regulatory programs. In general, landowner and timber harvester compliance with these best management practices is quite high, often exceeding 90 percent.

The positive condition of water quality flowing from forests should not imply a lack of opportunities for improvement. With regard to fish and wildlife generally, it is estimated that about 80 percent of the nation's flowing water from forest and nonforest sources can be improved in terms of quantity and quality, fish habitat, or composition of the fish community (USDA Forest Service 1994d). However, an estimated two-thirds of U.S. streams have habitat conditions that are adequate for sports fish. Considering only forests as a land cover type, there continues to be concern over the impact that forestry activities have on nitrate levels, water temperature, and suspended sediment. The latter is of special concern, especially following road construction and the application of some harvesting and grazing practices (Brown and Binkley 1994). Some practices in riparian areas also have raised concerns, especially removal of overstory along stream-banks, which can raise water temperatures enough to adversely affect fish survival.

Summary of Findings

Nonfederal forests provide a wide variety of benefits to the nation's citizens. These include employment and income opportunities, timber and wood products, nontimber forest products, urban and community benefits, recreational opportunities, and ecological benefits. In many cases, information regarding these benefits is limited because information on the type, magnitude, and value of benefits is not often collected or made available.