EXPERIENCES FROM AROUND THE WORLD

Marcel H. Cheyrezy

Bouygues Group

To describe European experience in promoting innovation in the building industry in just a few minutes is not an easy task, insofar as the subject is not addressed in precisely the same way in the various European countries. I shall concentrate on what I consider, in the context of my activities with the research and development (R&D) department of a major building and civil engineering group, to represent the most important specific aspects of the European approach in general and the French approach in particular.

The issue of promoting innovation is addressed in various ways. First, the research programs run by universities and public research centers generate innovations, which the most highly motivated construction companies then attempt to put into practice. A second approach takes the form of co-funded R&D between private companies and public authorities, decided at the national or European level. European funding to companies is distributed through various programs, of which the most important related to the building industry is the BRITE-EURAM program. This funding is equivalent to about 700 million U.S. dollars for the whole European industry with an estimated figure of $50 million for the building and civil engineering sector. This very limited support, which represents no more than a minute fraction of global production activity for our sector, is allocated to projects which must be multinational and precompetitive.

Insofar as funding at the national level is concerned, in France this takes a number of different forms. First are the R&D tax credits based only on the annual increase in R&D expenditure for the companies concerned. Then, we have interest-free loans from ANVAR, which is the National Agency for the Encouragement of Innovation. We also have co-funding for projects at the European level that associate the public authorities, companies, and national agencies. The High Performance Concrete 2000 project gives an example of the

magnitude of such projects: $4 million spent over a period of three years. In global terms, these different forms of support have a very limited impact.

In truth, the principal source of encouragement for innovation is indirect and stems from the contract procurement process. The standard practice in France corresponds to a situation where the building contractor is responsible for both the design and the build phases. This means that the leading construction companies possess highly competent design departments enabling them to submit variant solutions which give them the competitive edge. These variants act as a vehicle for the introduction and promotion of technical innovation. Nor should we forget the positive part played by the so-called approval-by-testing procedure. With regard to regulations, performance specifications represent a framework which provides the correct stimulus for the development of innovation, rather than the normative type specifications.

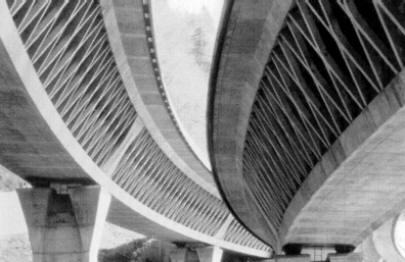

I will now turn to various recent examples of innovation in the construction industry. A major innovation of the last 10 years was the introduction of high-performance concrete with strength values of 60 MPa or more —that is, 8,000 psi or more. One example of the use of high-performance concrete was the Sylans Viaduct (shown in Figure 1), which was an innovative concrete truss. This bridge was awarded through a competitive bid which was limited to innovative projects. Thus, there was competition, but limited to projects that were not conventional. This is an example of innovation proposed by the construction company.

FIGURE 1 Sylans Viaduct

The Normandy Bridge gives an opposite example in which innovative design was introduced by the French Department of Transportation (DOT). This cable-stayed bridge, with a main span of 856 meters, provided the opportunity to acquire a number of new processes, including the use of a new very high-performance cement. My last example of a civil engineering project is the first offshore barge constructed in very high-performance concrete. This new form of construction, where the traditional material is steel, was made possible by using the high- performance concrete. It has very considerable weight saving, greater strength, and very high resistance to aggressive marine environments. The project was completed about a month ago, and the barge is 200 m long, 14 m wide, and 60 m high. This structure is heavily pre-stressed.

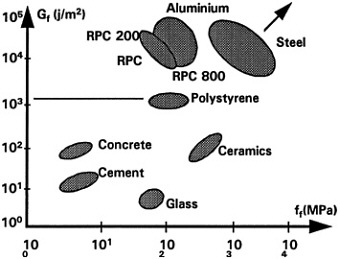

High-performance concrete is not limited to civil engineering applications only. Its use has spread rapidly to the building sector, the first main example being the Great Arch at La Defense in the inner suburbs of Paris. In order to ensure viability of the concrete to a height of 400 ft, a special concrete mix had to be developed. A further step was achieved in this long trend toward improved construction materials with the introduction of ultra high-strength cementicious matrices called RPC, which means reactive powder concrete. These concretes are prepared using powders with a particle size of less than 500 microns, increasing the strength of the material by a factor of four. With the addition of metal fiber, mechanical characteristics close to those of aluminum are achieved both in terms of ductility and bending strength as shown in Figure 2. When compared to steel, pre-stressed RPC has the same height, weight and strength.

Figure 2 Mechanical Characteristics of Reactive Powder Concrete

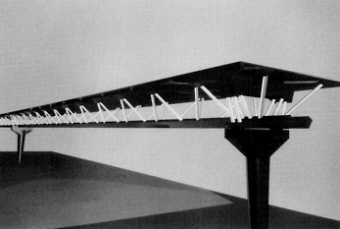

This material is still in its development phase, although a significant number of potential applications have already been identified. Figure 3 shows a single-span footbridge of 70 m we are considering. We are currently working on the design and manufacture of high-integrity containers for the storage of nuclear waste in collaboration with CEA, which is the French Atomic Energy Authority. We are also studying the construction of a foot bridge with a single span of 70 m. This bridge will be built in Sherbrooke, Canada, using a concrete with a strength exceeding 200 MPa—that is, 30,000 psi.

RPC technology has also been selected for our research program in the United States. The Construction Productivity Advancement Research program will extend over three years and is headed jointly by the Waterways Experimental Station of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and HDR, an American subsidiary of the Bouygues Group, in collaboration with four U.S. pre-cast concrete companies. Apart from the technology transfer aspects, the main objective is to demonstrate the advantages of RPC for the manufacture of pipes and pre-stressed poles. RPC was implemented for the first time in the United States in Minnesota.

My last example of innovative technology will be taken from the highway sector. Low noise highway pavement called Novachip was developed by our company in response to a performance-oriented call for tender issued by the French DOT. This pavement is now widely used in many countries, including the United States. We developed, at the same time of course, the machine which is necessary to apply this pavement.

FIGURE 3 Single-Span Footbridge Using Reactive Powder Concrete

In conclusion, I would say that in Europe, public funding is largely devoted to public R&D programs. These programs are generally insufficiently concerned with meeting the needs of the building sector. Therefore, the best form of promotion for innovation involves achieving the most open market procurement procedures possible with the adoption of performance-based rather than normative specifications. We have the impression that the situation in Europe in this context is a little bit better than in the United States. Some efforts, although still insufficient, are being made to move forward in this direction, with the application of procedures whereby contracts can be awarded to the best, rather than the lowest bidder, necessarily. Furthermore, the contracts for some projects include both construction and maintenance for a period of 10 years. These trends favor innovation, but also provide protection to the project owner. This approach must be extended and encouraged in Europe.

ABOUT THE SPEAKER

Toshiaki Fujimori is the head of the Technology Development Division, Shimizu Corporation, Tokyo, Japan. He began his career with Shimizu Construction Co. Ltd. as a research engineer in 1964 and has held several positions with the company including Deputy Director, Technology Division; Executive Vice President, Shimizu Technology Center America; General Manager, Shimizu Technology Division Overseas Technology Department; and General Manager, Shimizu Technology Division Planning Department. His research interests are in nondestructive testing, steel building construction, steel welding, and R&D management. Dr. Fujimori is a member of the Architectural Institute of Japan, Japan Society of Nondestructive Inspection, Japan Steel Fabrication Association, MITI, International Institute of Welding, American Society of Civil Engineers Corporate Advisory Board, Construction Industry Institute, The Japanese Society for Science Policy and Research Management, and Japan Society of Welding. He is also a member of the Japan Federation of Engineering Societies. Dr. Fujimori received his B.S. in architectural engineering from the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 1964; Licensed Architect 1st Class in 1968; and Ph.D. in engineering from the Tokyo Institute of Technology in 1975.

EXPERIENCES FROM AROUND THE WORLD

Toshiaki Fujimori

Shimizu Corporation

Several years ago, our Ministry of Construction asked, “What is the justification for the existence of the Ministry of Construction? ” The ministry began a “visioning” process to answer this question. They invited participants from the private sector, the leaders of the Building Association and other associations, and government. These groups worked together, and finally we achieved a national policy. The Shimizu Corporation also established a policy. Our policy says the construction industry exists to create a sustainable environment for human beings, society, and the ecosystems. Along with the internationalization of the global economy, the activities of the construction industry are crossing borders and limits of time. The infrastructure that we are building now is not only for ourselves, it is also for our future generations. We need to think about our children and grandchildren. We need to think beyond Japan, to think about the countries all over the world.

This national policy provided a framework to discuss the role of the construction industry's research and technology development. I think the construction industry's research and development (R&D) activity has six challenges for the twenty-first century, as follows:

-

Contribute to society and the environment

-

Focus on sustainable construction

-

Create new markets and generate paradigm shifts in construction systems

-

Revitalize existing markets by introducing new technologies and improving productivity in existing systems

-

Revitalize deteriorating infrastructure and enhance the construction site environment

-

Treat and reduce waste materials produced in construction projects.

To meet these challenges, the government should take the lead for contributing to society, focusing on sustainable development, revitalizing deteriorating infrastructure and treating and reducing waste materials. The private sectors should take the lead for creating new markets and revitalizing existing markets.

Ten years ago, we believed the key factors for the construction industry were quality, cost, delivery, safety. Today, these factors are not enough. Cost should include an evaluation of environmental impacts and delivery. For all factors, we need to think about their relationships to and impacts on the environment.

I'd like to talk about the role of the private and the public sectors in R&D. I believe the role of the private and public sectors in each country should be different because the conditions are different. My hobby is ancient history, so I would like to tell my story using Japanese history.

Three or four centuries before Christ, China had a big war, and in the southern parts of China, people escaped to the sea. Some people went to Vietnam. Some people went to the south of Korea, and many, many people came to the south of Japan. There they made this kind of small country, but there were almost 36 small countries, ancient Chinese literature said. They later had an outbreak of fighting, and they needed to build some embankments and dig some moats to protect against the enemy. Who can do this? Not the private sector but the government.

In the third or fourth century, our royal family was established. In the fifth century, the strongest emperor built the biggest tomb in the world, bigger than a pyramid. It was 500 m long. Who can do this? Not the private sector. A strong politician can do this.

Today there was a discussion of the Maglev experimental electromagnetically propelled high speed train. Why Maglev in Japan? The reason—there is a strong political leadership. Those big national projects foster innovative construction technology. The huge tomb built in the fifth century included a lot of construction technology. Today, government can still support big projects and can foster good technology, like the tunnel between France and the United Kingdom.

In the second century, Buddhism came to Japan from China and Korea. We built the old wooden-structure temples. Today, we have many national heritage resources. However, this year we had the great Hanshin earthquake, and many shrines and temples collapsed. Now we are discussing how to install the base isolation systems in the Buddha images and in the temples.

We are now discussing a new construction technology to maintain this kind of old structure. But who can do this? Shimizu? No. Who? Government. In this kind of research, I think the government should take the lead.

In the early 1600s, Japan started the Shogun Era. This continued about 300 years, and we had a strong policy of national isolation. Then, about 1860, Commander Perry came from the United States to open the door to Japan. Japan got a lot of technology from the United States, and, of course, from Europe. We changed from wooden structures to the best kind of brick or reinforced concrete buildings.

After the Second World War, the Ministry of Construction was formed to build large projects such as roads, bridges, dams, sewers and other infrastructure. Many military engineers joined the construction industry—the government research institute and the private sector. My first boss was a designer of fighter airplanes. Those engineers made a big contribution to the construction industry by bringing mechanization and modernization.

In 1964, the year of the Tokyo Olympics, I joined the Shimizu Corporation. The Olympics spurred a big construction boom. Japanese construction industry invested a lot in R&D, and many technologies were developed. One of the interesting technologies developed was steel structures. After the Tokyo Olympics, steel structures grew up and we had local investment in research. Today, I think 36 large private construction companies have their own research institutes.

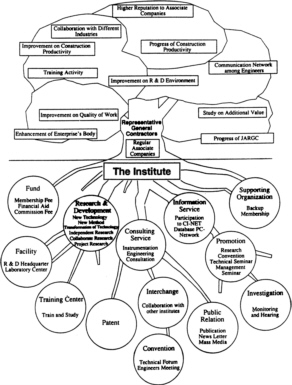

Then, small- and middle-sized general contractors also thought they should have a research institute because they were at a disadvantage when trying to receive building projects based on new technology. Fifty middle-sized general contractors gathered and established a central research institute for construction technology. The role of this institute is illustrated in Figure 1.

Shimizu started its research institute in 1940, and I think we have the best kind of research institute. I will briefly describe some of our activities in construction research and development. One technology is the treatment of slurry and muddy water. On a construction site, we cannot dump this muddy water into the sea, so we have to treat it. Otherwise, we have to stop the project. We invested a lot of money in this technology. The government is also working on this.

At Shimizu, R&D is not only intended to change the construction process, but also for capturing the market. An example is a vibration control system we developed. After developing these kind of systems, we received contracts for a lot of the tall buildings near the seaside, where there is a strong wind. First we developed the vibration control systems, then we developed a very good market for this technology.

New technology helps us capture markets. Another example is the highly effective magnetic shield systems, which also opened a new market. Today,

security is very important and security can create a new market. To use this technology, we are now trying to develop high security building systems. Another technology is an underground pumped storage dam. Next is a near-nature technology which puts concrete under the water where it can't be seen and plants and grass grow up on this new type of concrete. This also came from a new technology. Without new technology, we cannot capture new markets.

I would like to talk briefly about the government's role. Our Ministry of Construction last year unveiled their 5-year plan, which I think is a very good plan. The government's plan identified areas of relation between the Japanese government's policy and private construction firms' R&D strategy. The government gave industry a construction-related R&D vision for the twenty-first century within a large framework of environmental policies. The national R&D projects in 1994 were as follows:

National R&D Projects (1994)

-

Development of New Construction Technology

-

Less Resource and Less Energy Infrastructure Development

-

Development of Technology for Restoration, Alteration and Upgrading of Social Assets

-

Development of Technology for Protection of Large Cities from Earthquakes and Fires

-

Technology for Reduction of Construction Wastes and Enhancing Recycling

-

Development of Technology for Protection from Lava Flow Disasters

-

Development of Technology for Enhancing Harmonization with Nature

-

Development of Technology for Evaluating Performance Construction Materials.

To establish the future direction of the industry is the government 's role. Then, we can establish our own private company strategy.

For technology collaboration among foreign country governments to occur, government leadership is also needed. The Ministry of Construction 's 5-year plan for international collaboration contains the following items, including Japan-United States joint research for structures:

Five-Year Plan of Japan's Ministry of Construction (International Version)

-

Research for Global Geographical Information Infrastructure

-

Desertification Technology

-

Seismic Design Technology for Structures

-

Japan-U. S. Joint Research Structures

-

Research for Sewage in Tropical and Semi-tropical Areas (Developing Countries)

-

Restoration and Maintenance of Global Cultural Heritage (Developing Countries)

-

Survey on Utillization of Information and Automation Technology for Automobile Transportation (Domestic)

The 5-year plan includes not only the government, but private companies working to collaborate with foreign countries.

In closing, the construction industry exists to create a sustainable environment for human beings, society and the overall ecosystem. Research and development play an important role in the construction industry. Without doubt, government policy and large government projects foster innovation in Japan. For innovation to occur, collaboration among government, industry, academia, and foreign countries is essential. International cooperation would also help to save the Earth and limited R&D resources as well.

ABOUT THE SPEAKER

David L. Hawk is currently serving as an AT&T Industrial Ecology Fellow via a two-year research project by Corporate AT&T to identify a new model of industrial design and production with reduced environmental impacts. Dr. Hawk teaches architecture (building economics, technologies, project management, and the development process) and industrial management (international business, organizational behavior, and strategic management) courses. Dr. Hawk researches, teaches, and consults in two areas: (1) improving methods of international construction and (2) environmental management. He holds a dual professorship in the schools of Architecture and Industrial management at the New Jersey Institute of Technology and is a full member of the graduate faculty of Rutgers University. He has been a long-term visiting professor of the Institute of International Business at the Stockholm School of Economics. Dr. Hawk received his B.S. in architecture from Iowa State University, College of Engineering, in 1971; M.S. in architecture and M.C.P. from the University of Pennsylvania, Graduate School of Fine Arts, in 1974; and Ph.D in systems sciences from the University of Pennsylvania, Wharton School of Business, in 1979.

EXPERIENCES FROM AROUND THE WORLD

David L. Hawk

New Jersey Institute of Technology

There are many lessons to be learned about barriers to innovation and improved solutions from an international perspective. It allows a broader perspective when looking at problems here and is also a source of ideas for ways of doing things differently.

Comments presented here are the result of international construction research carried out over the past decade at the Stockholm School of Economics and the New Jersey Institute of Technology (NJIT). Sponsored by public and private clients, the work addressed questions regarding how construction was being changed via the process of internationalization.

Some of what I would like to share with you will show how aspects of our attitudes towards partnerships, innovation, and research are counterproductive and discourage innovation compared with the attitudes found in some other countries. This will come from the perspective of a consortium of 60 companies that joined a study to look at the future of the industry. Important to the future was how models of research found in other countries were showing considerable success.

The study illustrated that a major barrier to innovation is found in our own attitudes. The first obstacle to innovation was the attitude that R&D should not be internal to any company that designs or constructs facilities. Such was seen as a misuse of clients' money. Where R&D was needed, the belief was that the government should take responsibility. However, the catch was that the government should sponsor R&D projects and results that are of no particular utility to any industrial organization. To clearly help any organization was seen as a misuse of taxpayers ' money. While innovation becomes essential to a company, it should be restricted to areas of marketing, finance, and concrete mixes, not a deeper technological development of the industry.

Only when an industry appears to be threatened via international competition that can offer higher quality for a lower price are the above rationales for

business-as-usual suspended. Whether or not the business of U.S. construction practice is being so challenged is a key question. I believe the challenge is already present, especially, in the area of high-value-added building products. Many argue that it is not, since construction is uniquely protected by local, state and federal regulations and policies that keep out foreign approaches. A similar argument was made some years ago regarding autos, electronics and finance.

Another problem in attitude comes from our own success, leading to pride which encourages us to be closed to change, new ideas, or new ways of doing things. Some international examples show an American tendency toward arrogance and ignorance.

One example is the Messa office tower in Frankfurt, the highest building in Europe, organized by a large New York developer, designed by a well known Chicago architect, and constructed by a major German construction company. The tower was designed to be occupied by international clients that would make Frankfurt the financial center of the European Community. Its plan was economically difficult with a 66 percent net-to-gross ratio of rentable space. As such, the leading bank in Germany avoided the project. During the construction phase, the construction company decided to improve the efficiency of the design and reduce the energy-use requirements by putting in less lighting, thus needing less air-conditioning, thereby requiring reduced electrical services. The German engineers thought it prudent to lower the potential operating costs, increase the floor area, and shift the product towards a European standard of lower energy-use systems. The U.S. developer-owner was quite upset and forced them to remove what was done and return to the “international standards” per the original design. An executive of the German construction firm asked me, when next I met with the executive of the New York firm, to find out what those “international standards” were. It was New York standards that the developer had in mind, since he was planning to get many New York firms to rent space in Frankfurt, something that has yet to happen, partially because of the high operating costs of the building.

Canary Wharf is another example. It is a rather fantastic project south of London. However, the project seemed destined to fail from the start because it was built to what the American owners called international standards for world clients. When it went bankrupt, it had only attracted American clients. Once again, the standards were based on New York ideas of the utility of 20,000- to 50,000-sq-ft office plans with accompanying needs for massive amounts of artificial lighting and air-conditioning. One idea behind the development was to demonstrate that the European system of having office workers be within 20 ft of natural light and getting air from a window that opens was outdated. To this day I do not think the builders yet recognize that the arrogance behind this attitude is a limitation. The U.S. approach to “international standards” may even prove to be a problem at home in the United States.

Other thoughts about barriers to innovation come from a study and concluding symposium, called “Conditions of Success,” we did 5 years ago at the Institute of International Business, Stockholm School of Economics, with help from NJIT and Tokyo Metropolitan University. Sixty interesting major multinational construction-related companies, who were interested in changing the industry, participated. One objective was to study research and innovation in the industry to see where it was going and who would lead.

The group developed a chart of changes based on the industry as a value-added process. In the various stages in construction, the amount of value added shifts. At the idea stage, the one that focuses on client needs, the driving force in the industry in the 1970s was how to market to clients with a known need for a facility. The study group projected that during the 1990s, the driving force would move to creating clients who were previously unaware of their facility needs. This complemented a trend towards world-wide privatization of publicly owned facilities. In the second stage, the design stage, architects were sufficient for the needs of the 1970s. In the 1980s, engineers became the key. The study group projected that in the 1990s, organizing capabilities greater than those found in architecture and engineering would be needed. In the last stage, that of owning and using the product, success resides in the facility itself. Where a facility's features are sufficient, we simply rely on supply-side logic to get it produced, as during the 1970s. In the 1980s, the focus shifted to more value being added by more careful attention to demand side management and maintenance of the product. During the 1990s, the focus was projected to shift towards a need to increase the use-efficiency of the facility, not simply to worry about producing or maintaining it. This will result on a reduced need for standard office space and a greater need for space with sophisticated technical supports.

The study group considered design critical to the next decade of the industry, but not design as architects and engineers had learned it in school. Instead, design needed to be conceived as a higher-level organizing force requiring inquiry and innovation as part of a discovery process that focuses not on the final form of the product, which is the facility, but on defining the useful characteristics and conditions of the facility over time.

An example of the problem with rigidity in thinking about the form of the final product came up in a research project I have advised for a couple of years for a Finnish research institute I will talk about later. The project mission was to improve understanding of future production environments relative to the occupants, management, and communities. It tripped itself up at one point when traditional members of the building community insisted on keeping the issues loose while agreeing on a strong final form as the organizing force. I argued for the converse: that we should have clarity of vision but go easy on what form the solution should take.

This project was to decide from ground zero what the construction of future global production facilities would be like. One reason I was brought in was my notion that future factories would not be owned by GM, IBM, or the major companies but by their numerous suppliers because, increasingly, the suppliers have responsibility for the production and thus should have responsibility for the facility in which production takes place. This would insure greater facility flexibility to handle the demands for innovation than if the facility were managed by Toyota, GE, or other large concerns.

The tendency in our industry is to focus on the form of a project 's result. I believe this tendency comes from reliance on its products being projects. As a project, such things as timetables and qualities can be left loose and research is kept ambiguous, while the form is sacrosanct. Often we define the form of a project's result prior to much discourse about the characteristics and conditions of the project's result. We were discussing this problem in relation to the factory of the future in the Finnish study, when one architect in the group, who typified the industry focus on form, jumped up and said, “Forget about that. What we need to know is the form it 's going to be, and I think it should be an infinite sausage. One day you can take potato chips out; the next day you can make computer chips. That's the ideal factory.” The suggestion that the factory of the future should be a sausage with indiscriminate materials going in one end and anonymous products coming out the other was more or less the end of the project for several months, perhaps forever.

In the industry, we have to do much better relative to relating to other interests and other stakeholders. We need to learn to be much better listeners and much less arrogant. In my opinion, in the Finnish study, we could have examined questions of how to provide the suppliers, who have more responsibility for the R&D that gets done and the most to lose if things go badly, with a dynamic shelter for highly dynamic production conditions. The focus on form is as much a problem as our insistence that products are projects in construction. Construction industry clients are no longer impressed with our forms or projects.

In a questionnaire developed by the 60 companies, several issues were examined in terms of national preference. One issue for the seven countries represented in the study was what prevents application of new knowledge in the building industry. U.S. and British company executives felt new knowledge was not applied because cost-benefit analysis usually concluded that the pay-back was too far away. Only the Japanese felt not knowing the customer sufficiently well was the major impediment to applying new knowledge.

Another issue that was studied on the research was what the major management problem in the industry was. Almost all of these companies felt the major problem was attracting good people to the industry. This response was interpreted as meaning that we need to attract other kinds of people, perhaps a wider variety of disciplines, to construction.

One argument made by companies known for their high level of support for R&D was that R&D helps attract more diverse and talented university graduates. Some U.S. company executives pointed to some of the Japanese research areas, e.g., moon villages, special environments, and acoustical qualities, as quite silly. The Japanese pointed out that these projects had attracted some very interesting people into their organizations, people trained in disciplines that are not normally attracted to the work of construction companies. This may be a reason why Japanese firms can accommodate more diverse aspects of construction facilities. With it they can attract better people to better the industry.

The study group reached some very interesting conclusions about what companies could do to meet the changing mandates of the building industry in the future. Some of these dealt with new areas of research and technical development. Another area to look for new solutions is in the broader social arena, where new relationships between public and private sectors can be set up, particularly when it comes to innovation in R&D.

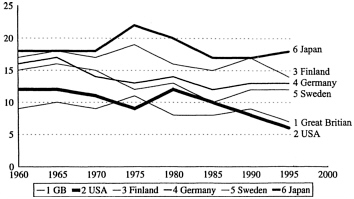

Our major trading partners in Europe and Asia are predisposed to combine public and private resources to bring innovation into construction as efficiently as possible. We are not so oriented. This may have to do with the relative value placed on construction, as reflected in Figure 1, which shows national gross domestic product (GDP) invested in construction.

FIGURE 1 Thirty-five years of national GDP; percent invested in construction sector

We can assume public and private bodies each have major, yet different roles in industrial society. Should these differences be left alone, defined in a way that places them in continual opposition, or coordinated for societal purposes above the limits of either? My comments support the argument that the two roles should be managed so as to strive for a common end, and that each can operate more efficiently if their differences are orchestrated under a common theme. At this point in the development of advanced industrial society, coordination seems to be taking on even more significant benefits. Why then, does the U.S. remain predisposed to building conflict into its relationships between public and private organizations?

Prior to presenting some aspects of the success gained in other nations by establishing innovative platforms for construction R&D, it is important to note that national conditions can seriously limit what any public body can accomplish. This is illustrated by the U.S. social bias for legalistic program establishment and management.

While not unique to the United States, my studies of international construction illustrate that the lawyer has an unusually powerful role in English-speaking countries. In the United Kingdom and the United States, countries with a common-law base to societal operations, there is an extensive reliance on legal skills to set political platforms, policy structures, and the entire tone of government's role in society. Elsewhere, professional attitudes other than litigation over potential to do wrong set the stage. This in part explains some of the major international differences in perception of how public and private sectors should relate, as well as how individual actors in the private sector should relate to each other.

To illustrate, I would like to draw on a study I did of another public sector in the 1970s. Two results from that work temper my enthusiasm for what we can accomplish in the United States in construction innovation, if we rely on a lawyer-directed legalistic base for policy making and program administration. The work was published as a report under the title, “Environmental Review: Analytic solutions in Search of Synthetic Problems.” It was based on research for a study funded by the Swedish Parliament to compare European and American approaches to environmental protection. It used multinational companies with similar production plants in various countries to examine different practices for environmental protection and determine their effectiveness in limiting industrial pollution. Originally the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was to be a joint sponsor of the work. Their rationale for withdrawal is instructive. They saw the project as too comprehensive to arrive at specifically helpful cases, and it relied too much on industry partners who needed to be watched, not learned from. EPA administration of the time felt they could learn very little from the Europeans since they believed they were already well ahead of them in this area.

In comparing American and Swedish approaches to environmental laws, it was clear that the objective of the U.S. system was to instill a legal order to force people to change their behavior. The basis for the Swedish approach was to achieve a negotiated order where innovative people would respond to difficult and diffuse environmental challenges.

All Swedish environmental laws (in 1976) could be found in a 25-page booklet. By contrast, just the U.S. water-quality laws and administrative rules required many hundreds of pages. I went to the writers and asked why this was so. To paraphrase the chief staffer, trained as a lawyer, who organized the writing of the U.S. law: “If you are trying to regulate a complicated system that is beyond understanding, then you must have laws that are complicated as well, perhaps not understandable.” The responsible party in Sweden, an economist-technologist, responded: “We in Sweden believe a precondition to obeying a law is that it is understood.”

The study results demonstrated that Sweden achieved better pollution control than did the United States. With the 1972 water-quality laws and later Superfund Act, we set up a system that always awaits clarification through legal case-law interpretations. This encourages greater employment of environmental lawyers than environmental engineers, resulting in 88 percent of Superfund resources spent to date going to lawyers instead of site clean-up. 1

Time has shown that the legalistic U.S. approach to environmental problems in the 1970s was politically inviting yet administratively impossible. The results have become too costly to administer. A New York Times series of articles beginning March 21, 1993 describes these results in great detail. The same legalistic framework is now present in early discussions of how best to respond to infrastructure problems in the United States, i.e., who is the most guilty for not having maintained the bridges.

The same pattern is seen throughout U.S. construction. As compared with other countries during the “Conditions of Success” symposium in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1990, the United States emphasizes the role of potential for litigation over the potentials in research and development. Some major U.S. construction companies define their innovation via the ability to avoid litigations, not activities to improve product qualities. Scandinavians on the other hand, tend to define quality in terms of integrity of thermal envelopes (e.g. 300 mm of insulation and triple glass windows). The Japanese differ from both and define it via how the surfaces line up and meet close tolerances. Americans tend to define quality by the number of projects completed without being sued for errors or omissions of contract dispute.

|

1 |

Breakdown from Rand Institute of Civil Justice Policy Report in 1992: 37 percent EPA litigation costs, 4-2 percent insured litigation costs, 9 percent other legal costs, and 12 percent Superfund cleanup (or 88 percent total legal costs). |

My final example regarding the undue importance the United States gives to the legal profession, comes from a freshman course I teach at NJIT. I have one of the lead real estate lawyers in the Northeast come in and talk to the class about the role of law in the construction industry. He talks at great length along a general theme of, “Get the lawyers in early and keep them late in the process.”

We follow his visit with the president of an American company that was bought out by a large European construction company. He explains how he saved 90 percent of their legal costs in the first year by following the advice of the new owners to draw up contracts with clients as if they were two people that were both going to gain something by the relationship, instead of two people opposing each other. Only after he has drawn up a contract with a client based on their mutual benefit does he allow the lawyers to look at it, but they are not allowed to change the tone or tenor of the contract.

In Northern Europe and Eastern Asia the public and private sectors interact as partners in the same organization, not as two sets of plaintiffs considering a law suit. Much more innovation is encouraged and accomplished in this atmosphere.

Two institutional innovations in Sweden and Finland illustrate a redefinition of government's role in improving the performance of their construction sectors in the next century. One is a new Swedish venture that opened last year, and another is a Finnish venture, which began in 1983. Each venture initiated a new kind of research infrastructure. This new infrastructure was designed to bridge traditional differences between theory and practice, public and private, designers and engineers versus producers and users. All these categories have become less discrete and less helpful over time and have even become barriers to progress. Both institutional ventures were set up to encourage innovation in how public activities can encourage private success in an international market. This also includes improvements to the ways in which success is measured.

These new institutions, established for construction-related, governmentally organized R&D programs, provide models of how to avoid bureaucratic institutions that have trouble with innovation. They also provide interesting examples of how to translate research and development into construction in the two European countries where they are based.

The major source of construction research funding in Sweden is the Swedish Council for Building Research (BFR). In contrast to the United States and many other nations, the BFR has a long history of significant funding for many disciplines and organizations doing research and development related to facility and infrastructure planning, design and production. About 50 percent of its funding goes to universities. Its level of funding has been declining in the last couple of years, but it has been and still is a major source of change for the industry in Sweden. Translating the amount of BFR funding from Swedish currency to American dollars in per capita terms—for the equivalent of a nation

of 265 million people funding research at the same level—would equal around $1.5 billion invested in building research. This is significantly more than the United States spends. This is why Sweden is known the world over for building research. BFR is now undergoing review and reorganization with some of the funding being allocated for new priorities.

In the meantime, alternative research efforts are underway. I would like you to look at one. It is a major new foundation that emerged in Sweden in January 1994 called MISTRA, “the Foundation for Strategic Environmental Research for Sweden's Future Competitiveness.” The foundation was started and is directed by Göran Person, the former head of Sweden's environmental protection agency's research division, former undersecretary of state in the Ministry of the Environment, and the person who funded the environmental research in the 1970s I referred to earlier.

The new foundation was set up to overcome some limitations in Swedish research. One study showed that 90 percent of the research the government sponsored came back too late to influence policy decisions. In other words, only 10 percent of the research results were in when an irreversible decision had to be made. In addition, it was noted that the role of politics was detrimental to long-term environmental research because politicians felt obliged to change priorities in response to shifting crises, many of which would impact their election. This new foundation was established to overcome these limitations as well as chart a new course with regard to how research is to be conducted. It was set up to illustrate new ways in which research is important to Sweden 's future.

The government set up the foundation with 2.5 billion Swedish Crowns (approximately $350 million, where approximately 7 Swedish Crowns equals 1 U.S. dollar). The foundation was established with three qualifications: (1) it will go out of business in 15 years, (2) politicians can not get involved in its decision-making process of research allocation, and (3) it concentrates on high-risk, high-return research that other more established organizations would not normally do. While its mission rests with environmental issues, these were clearly defined to include the planning, design and production of human environments, the facilities that society produces and uses in its social activities. In the first year of existence, the foundation has launched 11 projects. It also gives seed money to write proposals, rather than waiting for proposals to come in. Look for interesting results from this organization in the future.

Switching to Finland, we note that Finland has historically had a low level of publicly sponsored research, particularly in construction. During a history of easy trade with its large neighbor, the Soviet Union, it did not have to be concerned about the highly dynamic world of economic change to the west. Essentially, Neste, the big oil company in Finland, would take $4 to 5 billion worth of oil from the Soviet Union, process it, and give the money back in trade, that is, in goods and services, many of which were construction-related.

Perestroika and the demise of the Soviet Union in essence destroyed the Finnish construction industry as it was known until 1990. Although Finland's pre-Perestroika construction industry performed some remarkable feats with all that oil money, its underlying foundation and approach were overly nationalistic and arrogant about the need for future research investments. Does this sound familiar?

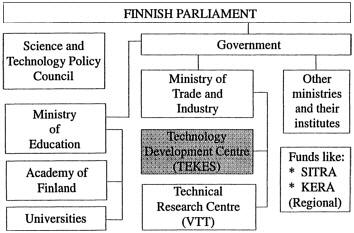

After some very rough times, something new is emerging in Finland, which I call Finland II. R&D is up considerably in construction. Forty percent of Finnish R&D is paid for by the government, and 50 percent of Finland's growth over the last five years can be attributed directly to this investment. Finland has one of the best growing economies in Europe these days. The seeds for this effort had been sown in 1983 with the founding of TEKES, the Technology Development Center of Finland. This effort was not much noted by the industry until its fruits began to appear just as they were so desperately needed in 1991. Figure 2 shows the place TEKES holds in the public sector encouragement of innovation.

In 1993 Finland invested about 11 billion Finnish Marks in research of which 6 billion was supplied by industry and 1.3 billion, or 25 percent of the government part, was allocated by TEKES. TEKES is somewhat similar to a combination of the National Science Foundation and the National Institute of Standards and Technology in the United States. Last year TEKES had 1.3 billion Finnish Marks, which is about 325 million U.S. dollars, for dedicated research. They fund projects 50/50 with companies throughout Finland. No funded projects are wholly done by universities or the government. It is all done with companies. Using the per capita equivalent multiplier again gives 17 billion U.S. dollars. (There are approximately 5 million Finns and approximately 4 Finnish Marks to 1 U.S. dollar). This is a considerable sum of money with which to get things going. Veli-Pekka Saarnivara is one of its directors. He heads the construction branch and initiates some very exciting work. He has visited the United States and has a good sense of what we do.

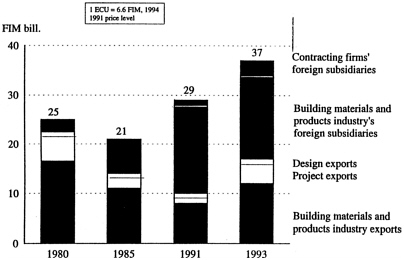

A recent evaluation by representatives from the common market concluded that TEKES had one of the most impressive records in translating government sponsorship into industry results in Europe. Part of this is seen in Figure 3 Internationalization of Finnish Construction. The joint public-private research work was found to have been very helpful to the construction industry's attempts to internationalize its products and processes. Of the 820 projects evaluated, 440 had led to commercially successful conclusions. The turnover from these had reached 5 to 6 billion European Community Units (ECU) by 1988, producing 3,100 to 5,300 new jobs and 2 to 4 billion ECUs of export income. (About 100 ECUs equal 128 U.S. dollars.) At some point TEKES resources will be shifted to other ends, but that is in the nature of adaptation.

In conclusion, changes to help the industry reinvent itself must come, first, from listening and not bringing arrogance or legalistic antagonism into our

ABOUT THE SPEAKER

Richard N. Wright has been Director of the Building and Fire Research Laboratory of the National Institute of Standards and Technology since 1991. His field of research includes analysis, behavior and design of structure, technologies for the formulation and expression of standards, performance criteria, and measurement technology for buildings. Dr. Wright is a fellow of the American Society of Civil Engineers and the American Association for the Advancement of Science and a member of Earthquake Engineering Research Institute Inc., Sigma Xi, and the National Society of Professional Engineers. Dr. Wright received his B.S. in 1953 and his M.S. in 1955 from Syracuse University and his Ph.D. in 1962 in civil engineering from the University of Illinois.